Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Cell Biology

Alternative pre-mRNA splicing is a process that allows for the generation of an extremely diverse proteome from a much smaller number of genes. In this process, non-coding introns are excised from primary mRNA and coding exons are joined together. Different combinations of exons give rise to alternative versions of a protein.

- alternative splicing

- mutant p53

- KRAS

- CMYC

- splicing factors

1. Introduction

Alternative pre-mRNA splicing is a common process in higher eukaryotes that allows for the generation of an extremely diverse proteome from a much smaller number of genes [1,2]. It is estimated that 95% of human multiexon genes undergo alternative splicing [3]. Alternative splicing plays a crucial role in development and tissue differentiation by providing proteins with different functions from the same set of genes [4]. Disruption of this process may result in disturbed cell differentiation and oncogenesis. The pattern of alternative exon selection in cancer resembles the one in corresponding embryonic tissues and involves the same regulatory pathways [5]. Multiple mRNA-Seq datasets comparing tumors and corresponding normal tissues demonstrate that an aberrant splicing landscape is a common feature of cancer [6,7,8]. Alternative oncogenic isoforms of different proteins are involved in all hallmarks of cancer: growth signal independence, avoidance of apoptosis, unlimited proliferation, genome instability, motility and invasiveness, angiogenesis, and metabolism [9,10].

mRNA splicing involves the spliceosome (a large ribonucleoprotein complex composed of snRNAs and associated proteins) and splicing regulatory factors [11]. In hematological malignancies, point mutations in spliceosome components (e.g., SF3B1, SF3A1, U2AF1, or ZRSR2) are more frequent, while in solid tumors, splicing is deregulated mostly by upregulation or downregulation of splicing regulatory factors (e.g., SRSF1, TRA2β, hnRNPA1, or QKI) [12]. Splicing is tightly regulated at various levels: by linking with transcription rate [13,14], expression, nonsense-mediated decay, and post-translational modifications of splicing factors [15,16,17]. In addition, relative levels of snRNAs U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6—basic components of the spliceosome—may also be important [18]. All of these can be disrupted by the activation of proto-oncogenes.

Altered splicing may also increase the activity of driver oncogenes and oncogenic signaling pathways via preferential expression of alternative pro-oncogenic isoforms, creation of new splice sites leading to the expression of cancer-specific isoforms, or indirectly via changed splicing of regulatory proteins. Specific examples will be discussed in the following paragraphs.

2. Alternative Splicing under the Control of Driver Oncogenes

2.1. CMYC

The oncogenic activity of CMYC in different cancers has been extensively studied and well documented. This proto-oncogene belongs to the family of transcription factors, along with NMYC and LMYC [23]. In normal tissues, its level is low and tightly regulated on the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level. In cancers, CMYC level is frequently increased via various mechanisms: gene amplification or translocation, upregulation of signaling pathways boosting CMYC activity, post-translational modifications, and increased protein stability [24,25]. Activated CMYC is a hallmark of many cancers and is required for their initiation and maintenance [26].

The transcriptional program of CMYC and its intersections with other oncogenes have been broadly discussed elsewhere [27,28]. Here, we will focus only on the role of CMYC in the regulation of alternative splicing and its consequences for oncogenesis. The globally increased transcription induced by CMYC requires adaptation of the splicing and translation machinery. The shortage of spliceosome components and splicing regulatory factors affects splicing profile [29,30]. CMYC hyperactivation increases translation of a core spliceosome component, SF3A3, through an eIF3D-dependent mechanism. This affects the splicing of many mRNAs, including those involved in mitochondrial metabolism favoring stem-cell-like, cancer-associated changes [31]. Koh et al. demonstrated that CMYC directly upregulates the transcription of several small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle assembly genes, including PRMT5, an arginine methyltransferase. This protein methylates Sm proteins that form the Sm core of the spliceosomal snRNPs U1, U2, U4/U6, and U5, and is critical for correct spliceosome assembly [32]. The perturbation in PRMT5 expression caused by CMYC leads mainly to intron retention or exon skipping and disturbs splicing fidelity [30]. CMYC not only causes overexpression of the most studied oncogenic splicing factor, SRSF1 [33], but also causes overexpression of several other proteins from the same family. Urbanski et al. identified an alternative splicing (AS) signature associated with high CMYC activity in breast cancer and showed that the change in AS is caused by the co-expression of splicing factors modules. They also demonstrated that overexpression of at least one module of the splicing factors SRSF2, SRSF3, and SRSF7 correlated with high CMYC activity across thirty-three cancer types [34].

The transcriptional activity of CMYC indirectly affects other oncogenes and key oncogenic processes by deregulating splicing. Through the overexpression of hnRNPH splicing factor, CMYC affects the RAS/RAF/ERK signaling pathway. A high level of CMYC and hnRNPH correlates with the expression of full-length A-RAF kinase. A-RAF activates oncogenic RAS signaling and inhibits apoptosis by binding to proapoptotic MST2 kinase. In cells with a low level of CMYC and hnRNPH, A-RAF is spliced into a shorter isoform that cannot bind to MST2. A-RAFshort still binds to RAS, but in a way that inhibits RAS activation [35]. One of the hallmarks of cancer is the conversion of glucose into energy via aerobic glycolysis instead of oxidative phosphorylation. This process is governed by PKM2, a pyruvate kinase isoform expressed mainly in embryonic and cancer cells, in contrast to the PKM1 isoform present in most adult normal cells. Overactive CMYC upregulates transcription of PTBP1, hnRNPA1, and hnRNPA2 splicing factors, resulting in a high PKM2/PKM1 ratio [36]. Zhang et al. found that another member of the MYC family, NMYC, similarly causes the upregulation of the same splicing factors, PTBP1 and HNRNPA1, leading to the expression of pro-oncogenic PMK2 isoform [37].

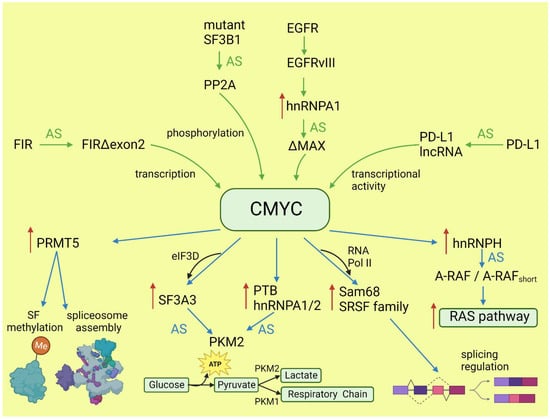

CMYC not only initiates transcription but also regulates transcription rate [38]. A pre-mRNA splicing occurs co-transcriptionally and the transcription rate influences the selection of alternative exons [13,39]. CMYC controls the transcription and splicing of a splicing factor, Sam68 pre-mRNA, in prostate cancer by binding to the promoter and increasing the RNA Pol II processivity [40]. Splicing factors (SF) frequently use an autoregulatory loop to control their own level: when SF protein level is high, it induces incorporation of a poison exon that triggers nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) of the transcript. In prostate and breast cancer, it was shown that CMYC not only increased the transcription of SRSF3 (and several other splicing factors) but also prevented incorporation of the poison exon [41]. The exact mechanism remains to be elucidated, but one may hypothesize that the exon skipping is caused by the increased transcription rate induced by CMYC. Selected effects of activated CMYC on splicing are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Effects of CMYC on splicing (blue arrows) and the influence of altered splicing on CMYC (green arrows). Red arrows: increased expression; AS: alternative splicing; SF: splicing factor.

2.2. RAS and Downstream Pathways

KRAS, together with NRAS and HRAS, belongs to the small GTPases family, which under physiological conditions cycles between active (GTP-bound) and inactive (GDP-bound) conformations in response to stimulation of cell surface receptors such as HER2, EGFR, or CMET. KRAS is commonly mutated in human cancers; however, the percentage of mutations varies between cancer types [42]. Mutations most frequently occur in codons for glycine at amino acid position 12 or 13, causing KRAS hyperactivity that contributes to its transforming properties [43]. Signaling cascades are triggered by the binding of the active RAS to RAS-binding domains within several known RAS effector pathways. The most important, in the cancer context, are the PI3K-AKT and MAPK signaling pathways [44].

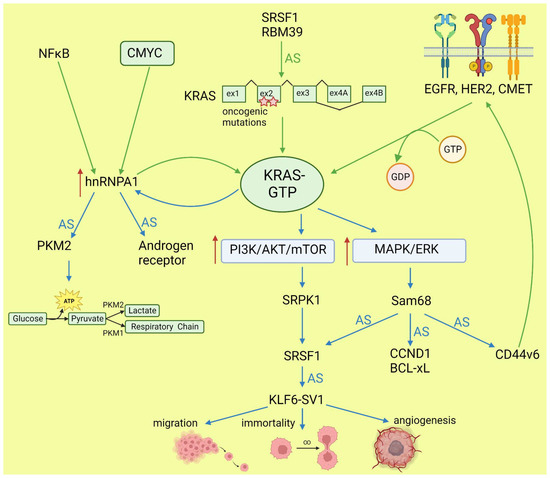

Lo et al. found that in lung cancer cells expressing either WT or mutant KRAS variants, the phosphorylation of SR splicing factors was reduced in those with mutant KRAS expression. This observation correlated with changed cassette exon skipping or inclusion in mutant vs. WT KRAS [45]. Correct phosphorylation of SR proteins by SRPK1 and CLK1 kinases is indispensable for their binding to splicing enhancer sequences on pre-mRNA [46]. It is known that signaling through PI3K/AKT activates SRPK1 kinase [47]; however, the link between RAS and SRPK1 activation was not directly demonstrated. In hepatocellular carcinoma, activation of the RAS/PI3K/AKT pathway leads to the expression of KLF6 splicing variant 1 (KLF6-SV1), which antagonizes the function of full-length KLF6 [48]. This protein is a tumor suppressor. The sorter isoform is an oncogene found in many tumors and involved in proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis [49]. KLF6 splicing is regulated by SRSF1 splicing factor [50]. Cheng et al. found a positive feedback loop involving activated RAS and an alternative isoform of CD44 (CD44v6) that can be a coreceptor of growth factor receptors. Activation of the RAS/MAPK/ERK pathway correlated with a preference for exon v6 inclusion. CD44v6, in turn, sustained signaling through tyrosine receptor kinases which activate RAS and downstream pathways, boosting cancer cell proliferation. The author suggested that this positive feedback loop could be a mechanism of the RAS-dependent pathway’s activation in cancers without oncogenic RAS mutations [51]. Alternative splicing of CD44 is regulated by a splicing factor, Sam68, which is phosphorylated by ERK, an effector of the RAS/MAPK/ERK pathway [52]. The same signaling pathway may be responsible for alternative pro-oncogenic splicing of other Sam68-dependent genes, namely, CCND1, SRSF1, BCL-xL, and mTOR [53]. Notably, mTOR is a key effector part of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway that can be activated by RAS [44]. The effects of mutated KRAS on splicing are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Effects of KRAS on splicing (blue arrows) and influence of altered splicing on KRAS (green arrows). AS: alternative splicing; red arrows: increased expression or pathway activity.

2.3. Mutant p53

The TP53 gene is a tumor suppressor, while its hotspot mutants gain oncogenic activity (named gain of function, GOF) and are involved in all hallmarks of cancer [54]. In contrast to wild-type proteins, p53 GOF mutants do not bind directly to promoters, but interact with different transcription factors to control expression of target genes [55]. In addition to transcription control, p53 mutants contribute to oncogenesis via interaction with TAp63 and TAp73 [56] to inhibit their proapoptotic activity, and with ID4 in angiogenesis stimulation [57,58].

While many researchers have studied the alternative splicing of the TP53 transcript and demonstrated the role of alternative isoforms in cancer development (discussed in more detail later), little is known about the role of mutant p53 in alternative splicing regulation. Escobar-Hoyos et al. demonstrated that in pancreatic cancer, mutant p53 upregulates the expression of hnRNPK splicing factor. This leads to the mis-splicing of GAP proteins and activates the oncogenic RAS pathway [59]. In addition, the RNA-Seq results underlying this study indicate other genes alternatively spliced under the influence of the p53 mutant. Pruszko et al. found, in breast cancer, a ribonucleoprotein complex composed of mutant p53, a splicing factor SRSF1, ID4, and lncRNA MALAT1. The complex altered a splicing of the VEGFA transcript, thus promoting proangiogenic isoforms over antiangiogenic isoforms [58]. A proangiogenic role of the studied complex was confirmed in vivo in a zebrafish model [60]. These two independent studies indicated that GOF p53 mutants influence alternative splicing in cancer. However, published results are limited to two cancer types and focused on a few target genes. Further studies based on a broad spectrum of tumors are needed to understand the role and interactions with other oncogenes of the GOF p53 mutants in alternative splicing regulation.

3. Driver Oncogenes Regulated by Alternative Splicing

3.1. TP53 Regulation by Splicing

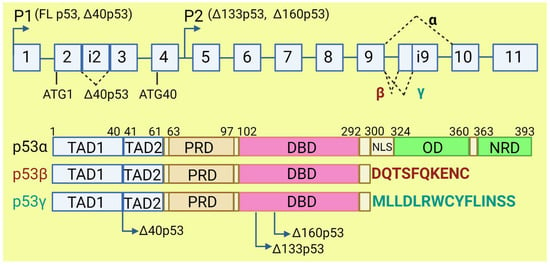

The TP53 gene produces at least 12 isoforms with different features that might prevent or promote cancer development. The canonical, full-length p53 (FLp53) protein has seven functional domains: N-terminal transactivation domains TAD1 and TAD2, a proline-rich domain, a DNA-binding domain, a nuclear localization signal, an oligomerization domain, and a negative-regulation domain [61]. The α (full-length), β, and γ variants of p53 result from alternative splicing of the C-terminus. β and γ isoforms are formed by partial retention of intron 9 (i9). The resulting alternative exons, 9b or 9g, contain a stop codon, leading to the replacement of the oligomerization domain into 10 amino acids (DQTSFQKENC) in p53β and 15 amino acids (MLLDLRWCYFLINSS) in p53γ (Figure 3). SRSF1 and SRSF3 regulate the splicing of i9 and favor the expression of FLp53 [62,63]. Marcel et al. observed that inhibiting CLK kinase or silencing SRSF1 upregulated the expression of p53β and p53γ isoforms in the breast cancer cell line MCF7 [63]. In contrast to SRSF1 and SRSF3, SRSF7 has been reported to enhance p53β expression in response to ionizing radiation [64]. Each of the α, β, and γ isoforms may also be changed from the N-terminus through alternative splicing of intron 2 (Δ40), alternative start of translation from internal IRES (Δ40, Δ160), or transcription from internal promoter (Δ133, Δ160) [65,66] (Figure 3). The co-expression of so many isoforms and the difficulty of distinguishing between them using available molecular biology methods make it challenging to evaluate their role in cancer.

Figure 3. The human TP53 gene and p53 isoforms. (Upper panel): schematic representation of TP53 gene. Exons are numbered from 1 to 11. Alternative splicing of introns i2 and i9 provides alternative p53 isoforms. P1 and P2: alternative promoters. ATG1 and ATG40: alternative transcription start sites. (Lower panel): representation of p53 domains. TAD: transactivation domain; PRD: proline rich domain; DBD: DNA binding domain; NLS: nuclear localization signal; OD: oligomerization domain; NRD: negative regulation domain. Isoforms β and γ lack C-terminal domains, including OD, replaced by DQTSFQKENC and MLLDLRWCYFLINSS, respectively. Isoforms Δ40p53, Δ133p53, and Δ160p53 have a deletion from N-terminus.

The p53β and p53γ isoforms, often described as antioncogenic, may have important implications for cancer prognosis and therapy [67]. Bourdon et al. observed that breast cancer patients who co-expressed mutant p53 and p53γ had much better prognosis, lower recurrence rate, and longer overall survival than those who had only mutant p53 expression [68]. It would be worthwhile studying if high levels of SRSF1, frequently observed in cancers, contribute to the GOF of p53 mutants by preventing expression of p53β and p53γ isoforms. These isoforms retain the ability to induce the expression of wild-type p53-dependent genes. P53β increases the transcriptional activity of p53α on p21 and BAX promoters, while p53γ only increases its activity on BAX promoters [63]. However, p53β poorly activates MDM2 promoters, which may decrease p53 degradation and contribute to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Due to the lack of tetramerization domain, p53β and p53γ cannot form a complex with full-length p53, but they precipitate together when bound to a p53-responsive element on the promoter [63].

The overexpression of Δ40p53 isoform was observed in different neoplasia: in breast cancer and acute lymphocytic leukemia it was correlated with worse clinical outcome [69,70], while in melanoma and ovarian cancer it was connected with better prognoses [71,72]. Further, in vitro studies in cancer cell lines provided contradictory observations [65]. This discrepancy may be related to the proportion between Δ40p53, FLp53, and other p53 isoforms, on the one hand, and mutations in the TP53 gene, on the other, but further studies are needed before Δ40p53 can be used as a prognostic biomarker [65,73]. Generally, higher expression of Δ40p53α rather inhibits p53′s suppressive activity, but equal or lower expression might support p53 features. The effect of Δ40p53α on FLp53 activity might also be cell-specific [73]. All Δ40p53 isoforms lack part of the N-terminal transactivation domain, TADI, but retain the second part, TADII. Therefore, Δ40p53 in a complex with FLp53 can prevent expression of TADI-dependent genes but retains the ability to activate TADII-dependent genes in a complex or independently from FLp53. The Δ40p53-FLp53 complex binds to target genes in the form of heterotetramer (a dimer of dimers) [74]. Δ40p53, independently from FLp53, regulates expression of antiapoptotic ligand netrin-1 and its receptor, UNC5B. Netrin-1 is overexpressed in several aggressive cancers, such as melanoma, colorectal cancer, and breast cancer, and its expression correlates with the expression of Δ40p53 [75]. Δ40p53α lacks a binding site for MDM2 and lacks major activating phosphorylation sites. Δ40p53 may reduce FLp53 degradation since heterotetramers which contain Δ40p53 have disturbed binding to MDM2 [73]. High expression of Δ40p53 is observed in embryonic tissues, where it contributes to the pluripotency, proliferation, and migration of the cells [76], suggesting that a similar role may be played in cancer stem cells, which requires further research.

The Δ133p53 isoform lacks the transactivation domain, the proline-rich domain, and part of the DNA binding domain [61]. It can form heterotetramers with FLp53 and other p53 isoforms which contain the oligomerization domain. Therefore, Δ133p53 affects the transcriptional activity of FLp53. Many scientific reports indicate that Δ133p53 does not cause malignant transformation [66,77], but it may be important for the progression of benign to aggressive tumors [78,79]. Δ133p53 is overexpressed in gastric, colon, lung, and breast cancers, and in melanoma [79,80,81,82]. The overexpressed Δ133p53 isoform contributes to cancer invasiveness by upregulating the JAK-STAT and RhoA-ROCK signaling pathways. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) contributes to proinflammatory and oncogenic phenotype and acts as mediator of this process [83]. In contrast to FLp53, Δ133p53 inhibits antiangiogenic factors, such as interleukin 12A and matrix metallopeptidase 2, and upregulates proangiogenic factors such as angiogenin, midkine, hepatocyte growth factor, and angiopoietin-like 4. However, silencing of p53 has no impact on the expression of these genes. The ratio of p53 to Δ133p53 may influence the expression of anti- and proangiogenic factors. It was indicated that all isoform variants of Δ133p53 except Δ133p53β stimulate angiogenesis in tumors [84]. Overexpression of Δ133p53 is also linked to upregulation of MDM2, which might influence p53 degradation [85]. Δ133p53 isoform is able to inhibit p53-mediated apoptosis and G1 cell cycle arrest without inhibiting p53-mediated G2 cell cycle arrest in response to doxorubicin treatment. This is possible due to the downregulation of p21 and upregulation of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 by this isoform. Downregulation of Δ133p53 leads to upregulation of proapoptotic protein NOXA. Silencing of Δ133p53 also elicits an increase in caspase 3 cleavage [85]. Upregulation of Δ133p53 with simultaneous downregulation of p53β leads to the inhibition of p53-mediated replicative senescence in human fibroblasts. Overexpression of Δ133p53 with concomitant downregulation of p53β was observed in colon carcinoma, whilst in benign adenoma, the profile of p53 isoform expression was the opposite. This suggested that carcinoma escaped from the senescence barrier. The influence of Δ133p53 on senescence might be caused by altering p53 target genes’ activation, e.g., by a tumor suppressor, miR-34a, which induces apoptosis, senescence, and G1 cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage [80].

Candeias et al. demonstrated that cancer cells overexpressing Δ160p53 present a phenotype just like cells with GOF p53 mutants: increased survival, proliferation, invasion, and altered tissue architecture. In their research model, expression of full-length mutant p53 without Δ160p53 caused a lack of cancer hallmarks. Knockdown of mutant p53 did not result in restoring apoptosis without knockdown of Δ160p53 [86]. The Δ160p53β isoform was found in U2OS, T47D, and K562 cancer cell lines and treatment with hemin decreased its expression [87]. In melanoma, Δ160p53 isoforms can stimulate proliferation and migration. Treatment with anticancer drugs such as doxorubicin, etoposide, and cisplatin leads to upregulation of Δ160p53 in melanoma cells [88].

In cancer, mutations within the coding sequence are the most studied and best understood. Far fewer studies focus on mutations in introns and their consequences for proper splicing. Several studies indicate that such mutations account for a low percent of all point mutations in TP53 and can lead to a truncated protein lacking the C-terminal domain [89,90,91]. Splicing mutations in TP53 may be associated with poorer survival prognosis compared to wild-type p53 [92]; however, they are more difficult to detect and it is more difficult to predict the outcome [93].

GOF p53 mutants are characterized by greater stability compared to the wild-type protein. One mechanism for this phenomenon is related to the alternative splicing of E3 ubiquitin ligase MDM2 [94,95]. In normal cells, MDM2 ubiquitylates and targets p53 for degradation [96]. MDM2 amplification or overexpression is observed in many cancers [97,98]. However, MDM2 does not prevent accumulation of mutant p53 in tumors [99,100]. The most abundant alternative isoform of MDM2 overexpressed in cancers is MDM2-ALT1 (MDM2-B), which lacks a p53-binding domain. The alternative splicing of MDM2 is controlled by SRSF1 and SRSF2 working in an opposing manner: SRSF1 promotes exon 11 skipping and MDM-B expression while SRSF2 prevents exon 11 skipping [101,102]. MDM2 forms dimers and/or oligomers by the RING domain, and this process is necessary for efficient ubiquitination of p53. MDM2-B retains the RING domain and, thus, the ability to bind to MDM2, thereby blocking p53 ubiquitination. Moreover, MDM2-B increases MDM2 cytoplasmic localization and, consequently, decreases its binding to mutant p53 in the nucleus [99]. Aptullahoglu et al. demonstrated that spliceosome inhibition leading to aberrant MDM2 splicing can be used to treat wild-type p53-expressing tumors. They combined E7107 spliceosome inhibitor with RG7388 MDM2 inhibitor to block the E3 ligase on the splicing and protein level, provoking the accumulation of p53 and apoptosis. In addition, inhibition of the spliceosome resulted, by intron retention, in the expression of the p21 isoform, which was unable to inhibit the cell cycle and protect cells from apoptosis [103].

3.2. CMYC

Functional alternative isoforms of CMYC are not reported in the literature but alternative splicing of other proteins may affect CMYC activity in cancers. FUSE-binding protein-interacting repressor (FIR) is a suppressor of CMYC transcription. A splice variant of FIR that lacks exon 2 in the transcriptional repressor domain (FIRΔexon2) presents dominant negative activity towards full-length FIR; thus, the expression of FIRΔexon2 upregulates CMYC transcription. The increased ratio of FIRΔexon2/FIR contributes to human colorectal and hepatocellular carcinomas as well as lymphomas [104]. Mutations in SF3B1, the gene coding the most commonly mutated spliceosome component across cancers, alters the splicing and promotes the decay of mRNA, coding a specific subunit of the PP2A serine/threonine phosphatase and increasing phosphorylation and, consequently, the stability of CMYC [105]. This observation is particularly valuable, because SF3B1 may be targeted with several inhibitors, and it was demonstrated that patients with overactive MYC are more sensitive to these drugs [29]. In lung adenocarcinoma, under the influence of IFNγ, the protein coding gene PD-L1 may be spliced into long non-coding RNA PL-L1-lnc. This alternative transcript does not encode a protein but is functional. Through direct interaction with CMYC, it boosts its activity as a transcription factor and contributes to the increased proliferation and invasiveness of neoplastic cells [106]. EGFRvIII is a constitutively active variant of EGFR formed by genomic rearrangement. It is highly expressed in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), where is detected at an overall frequency of 25–64% [107]. EGFRvIII induces a broad change in the alternative splicing program via upregulation of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 splicing factor. HnRNPA1 promotes inclusion of exon 5 in the transcript encoding the CMYC-interacting partner MAX. The resulting shorter isoform ΔMAX enhances CMYC-dependent transformation [108]. The impact of alternative splicing on CMYC is summarized in Figure 1.

3.3. KRAS and Downstream Pathways

KRAS may be spliced into two isoforms with alternative exon 4: KRAS4A and KRAS4B. Both isoforms are oncogenic if they have a mutation in G12 or G13 [109]. The two isoforms differ in their C-terminal domain, referred to as the hypervariable region (HVR), which determines the possible post-translational modifications and membrane localization [110]. Although most of the interactome is the same for both isoforms, some proteins interact specifically with one or the other [111,112]. This is related to the distinct association to the membrane and intracellular localization. For example, KRAS4A undergoes palmitoylation–depalmitoylation cycles, unlike KRAS4B. This allows it to bind to heterokinase HK1 on the outer mitochondrial membrane and stimulate HK1 activity, thereby increasing glycolysis in cancer cells [113]. Moreover, KRAS4A binds more strongly to RAF1, augmenting downstream ERK signaling and anchorage-independent growth [112]. The regulation of KRAS splicing in cancers is not clear. Hall et al. reported that in colon cancer with inactive APC, the key role is played by SRSF1 [114]. KRAS4A expression may be also decreased by splicing inhibitor Indisulfam, which targets the protein RBM39 associated with the spliceosome [115] (Figure 2).

Alternative splicing also affects downstream components of RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways [116]. A-RAF, B-RAF, and C-RAF can be spliced into dominant-negative isoforms with only an RAS-binding domain or constitutively active, oncogenic isoforms containing only a kinase domain. The splicing of A-RAF in cancer is regulated by hnRNPH, and indirectly by CMYC, which upregulates the level of the splicing factor [35]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, it was demonstrated that hnRNPA2 also causes constitutive activation of the RAS pathway by the splicing of A-RAF [117]. The MKNK2 gene is expressed as two isoforms: MNK2a and MNK2b kinases. The alternative splicing of MKNK2 is regulated by proto-oncogene SRSF1 [118]. While MNK2a can suppress RAS-induced transformation, MNK2b is pro-oncogenic. It phosphorylates the translation initiating factor eIF4E—an effector of RAS-dependent pathways—increasing translation in cancers [119]. In the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway, both PI3K and mTOR may be spliced into more active oncogenic isoforms [120,121]. The mTORβ isoform, despite losing most of the protein–protein interaction domains, retains its kinase activity and ability to complex with Rictor and Raptor proteins. Most importantly, mTORβ accelerates proliferation by shortening the G1 phase of the cell cycle, and its overexpression is sufficient for immortal cell transformation [121]. Increased activation of AKT further affects aberrant alternative splicing by phosphorylation of SRPK kinase [47].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers15112918

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!