Mesoamerica is a historically and culturally defined geographic area comprising current central and south Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, and border regions of Honduras, western Nicaragua, and northwestern Costa Rica. The permanent settling of Mesoamerica was accompanied by the development of agriculture and pottery manufacturing (2500 BCE–150 CE), which led to the rise of several cultures connected by commerce and farming. Hence, Mesoamericans probably carried an invaluable genetic diversity partly lost during the Spanish conquest and the subsequent colonial period. Mesoamerican ancient DNA (aDNA) research has mainly focused on the study of mitochondrial DNA in the Basin of Mexico and the Yucatán Peninsula and its nearby territories, particularly during the Postclassic period (900–1519 CE).

- ancient DNA

- Mesoamerica

- mtDNA

- Native American founding lineages

- Native American genetic history

- Native American ancestries

1. Mesoamerican Genetic Studies

Mesoamerica was home to different human cultures connected by commerce and farming, and whose varied genetic backgrounds created an invaluable source of genetic diversity in the continent. Previous studies have attempted to uncover the peopling process of Mesoamerica using genetic approaches on modern-day Indigenous and cosmopolitan populations, mostly from Mexico and Guatemala. These analyses mainly focused on studying the so-called uniparental markers: the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)

[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11]

and the Y-chromosome

, which allow for demographic inference of maternal and paternal ancestries, respectively. Other studies further analysed single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs—variable genomic positions that are present at a frequency ≥1% in the population) located on the autosomes (non-sex chromosomes)

, or sequenced complete exomes (genomic regions that encode proteins) in order to describe Mexican genetic variation, population history, adaptation to the environment, and potential implications for biomedical research

[17]

. Importantly, this body of work contributes valuable data to describe the global human genetic diversity, especially since Indigenous populations from the Americas are among the most underrepresented populations in human genomic studies

.

Most of these genetic studies proposed a single origin for Mesoamerican populations

, instead of a dual origin as previously argued by Mizuno et al. (2014)

[10]

. Moreover, Sandoval and colleagues

analysed the Indigenous population substructure. They demonstrated that the patterns observed by analysing uniparental markers do not display significant population stratification in relation to linguistics, implying that genetic divergence preceded linguistic diversification. It was also shown that modern-day Mesoamerican-related populations contain higher levels of genetic diversity and lower levels of autozygosity (DNA segments identical by descent) compared to modern populations related to other cultural areas, such as Aridoamerica (Figure 1)

. These observations agree with the hypothesised importance of agriculture and trade in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica compared to the Aridoamerican hunter-gatherer lifestyle from the northern regions, to foster population movements and admixture that increase genome-wide levels of genetic diversity.

2.

Ancient DNA Studies

Inferring the population history of Mesoamerica through genetic studies that solely incorporate modern-day populations can be challenging due to recent historical events, such as population admixture with European, African, or Asian populations, that can distort pre-colonisation genetic signals. For instance, present-day Mexicans have, in general, three different ancestries: Native American, European (closely related to Iberians), and African. While the African component is generally minimal, the European component has a much lower proportion in Native Mexicans than what is found in cosmopolitan Mexicans. Notably, the Native American ancestry component can be divided into six separate ancestries

[16]

. Three of these are restricted to isolated populations of the northwest, southeast, and southwest, while the other three are widely geographically distributed

[16]

. Hence, it is essential to include pre-colonisation samples from the archaeological record to contextualise the true genetic diversity and population substructure of ancient Mesoamerica and identify genetic ancestry that might have been lost since the arrival of the Spanish.

In spite of the extensive archaeological, linguistic, and anthropological research on pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, there have been surprisingly few aDNA studies. Therefore, there is a current lack of genetic knowledge about the genetic history of the region, probably because of the highly degraded nature of genetic material from tropical environments. Thus, currently available ancient genetic data rely mostly on mtDNA studies. The human mtDNA is a circular double-stranded DNA molecule that is maternally inherited, does not recombine

, and has a higher mutation rate compared to the nuclear genome

[23]

. The sizes of the human reference mtDNA sequences rCRS

[24]

and RSRS

[25]

are small at 16,569 base pairs. These characteristics make mtDNA a suitable tool for maternal phylogenetic and phylogeographic inferences

[26]

. In addition, the high copy number of mtDNA in cells increases the odds of successfully obtaining ancient mtDNA in archaeological remains

. Mitochondrial haplogroups are lineages defined by shared genetic variation. They have been used to represent the major branches along the mitochondrial phylogenetic tree, unravelling the evolutionary paths of maternal lineages back to human origins in Africa and the subsequent peopling of the world. The Indigenous haplogroups found in present-day non-Arctic populations from the Americas are A2, B2, C1, D1, and D4h3a. All of them descend from a founding population that split from Northern Eurasian lineages ~25,000 years ago and remained stranded in Beringia for ~6000 years before starting to colonise the Americas ~16,000 years ago

[29][30][31]. However, there are limitations associated with the study of mtDNA. Indeed, mtDNA represents the evolutionary history of the female population at a single locus and sample sizes are often small. Therefore, it is necessary to remain cautious when interpreting mtDNA results mainly when there is disagreement with those obtained from genome-wide analysis. Nevertheless, most pre-Columbian Mesoamerican genetic data (Tables 1 and 2) originate from general diagnosis of mtDNA haplogroup variants in the control and/or coding regions. This early technique tested restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) which, in this case, result from the presence or absence of mitochondrial sites cleaved by restriction enzymes in order to characterise the mitochondrial haplogroups. Although RFLPs were reported in earlier studies, the partial or complete sequencing of the mitochondrial Hypervariable Regions 1 and 2 (HVR1 and HVR2, respectively) rapidly became the most common strategy to study mtDNA history. Only a few studies in Mesoamerica have been recently able to reconstruct complete ancient mitogenomes

. However, there are limitations associated with the study of mtDNA. Indeed, mtDNA represents the evolutionary history of the female population at a single locus and sample sizes are often small. Therefore, it is necessary to remain cautious when interpreting mtDNA results mainly when there is disagreement with those obtained from genome-wide analysis. Nevertheless, most pre-Columbian Mesoamerican genetic data (Tables 2 and 3) originate from general diagnosis of mtDNA haplogroup variants in the control and/or coding regions. This early technique tested restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) which, in this case, result from the presence or absence of mitochondrial sites cleaved by restriction enzymes in order to characterise the mitochondrial haplogroups. Although RFLPs were reported in earlier studies, the partial or complete sequencing of the mitochondrial Hypervariable Regions 1 and 2 (HVR1 and HVR2, respectively) rapidly became the most common strategy to study mtDNA history. Only a few studies in Mesoamerica have been recently able to reconstruct complete ancient mitogenomes

and only one has also generated and analysed genomic data

[35].

.

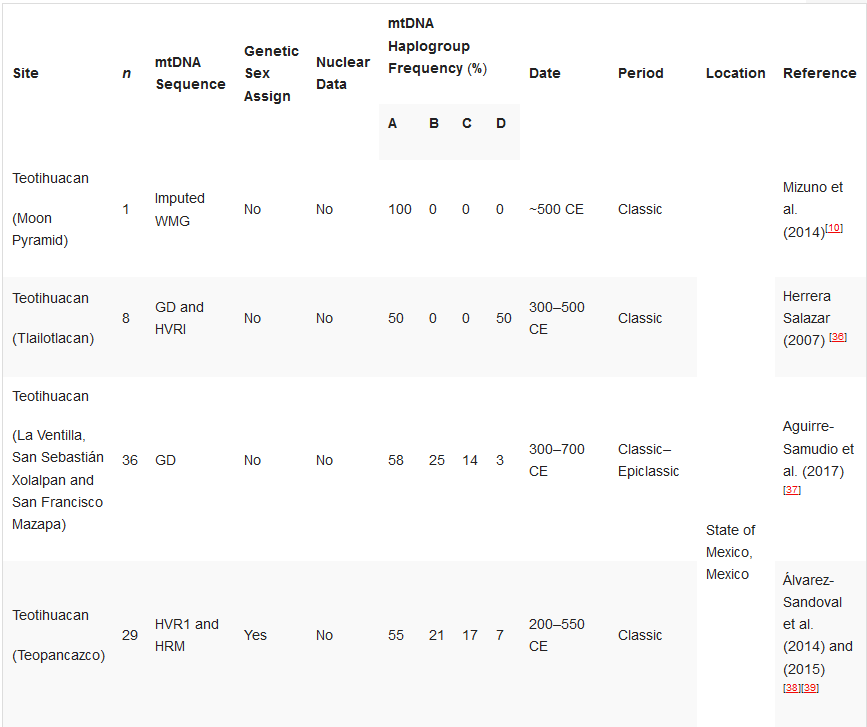

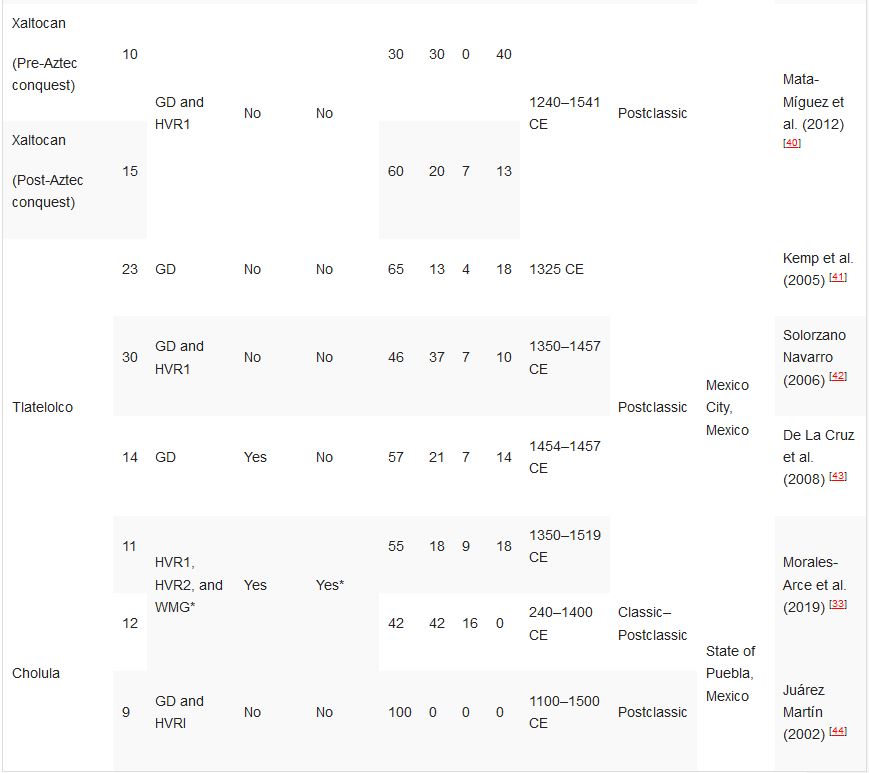

Table 12. Ancient DNA studies in the Basin of Mexico.[10][33][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44]

Ancient DNA studies in the Basin of Mexico.

|

Site |

n |

mtDNA Sequence |

Genetic Sex Assign |

Nuclear Data |

mtDNA Haplogroup Frequency (%) |

Date |

Period |

Location |

Reference |

|||

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

|||||||||

|

Teotihuacan (Moon Pyramid) |

1 |

Imputed WMG |

No |

No |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

~500 CE |

Classic |

State of Mexico, Mexico |

Mizuno et al. (2014)[10] |

|

Teotihuacan (Tlailotlacan) |

8 |

GD and HVRI |

No |

No |

50 |

0 |

0 |

50 |

300–500 CE |

Classic |

Herrera Salazar (2007) [36] |

|

|

Teotihuacan (La Ventilla, San Sebastián Xolalpan and San Francisco Mazapa) |

36 |

GD |

No |

No |

58 |

25 |

14 |

3 |

300–700 CE |

Classic–Epiclassic |

Aguirre-Samudio et al. (2017) [37] |

|

|

Teotihuacan (Teopancazco) |

29 |

HVR1 and HRM |

Yes |

No |

55 |

21 |

17 |

7 |

200–550 CE |

Classic |

Álvarez-Sandoval et al. (2014) and (2015) [38][39] |

|

|

Xaltocan (Pre-Aztec conquest) |

10 |

GD and HVR1 |

No |

No |

30 |

30 |

0 |

40 |

1240–1541 CE |

Postclassic |

Mata-Míguez et al. (2012) [40] |

|

|

Xaltocan (Post-Aztec conquest) |

15 |

60 |

20 |

7 |

13 |

|||||||

|

Tlatelolco |

23 |

GD |

No |

No |

65 |

13 |

4 |

18 |

1325 CE |

Postclassic |

Mexico City, Mexico |

Kemp et al. (2005) [41] |

|

30 |

GD and HVR1 |

No |

No |

46 |

37 |

7 |

10 |

1350–1457 CE |

Solorzano Navarro (2006) [42] |

|||

|

14 |

GD |

Yes |

No |

57 |

21 |

7 |

14 |

1454–1457 CE |

De La Cruz et al. (2008) [43] |

|||

|

11 |

HVR1, HVR2, and WMG* |

Yes |

Yes* |

55 |

18 |

9 |

18 |

1350–1519 CE |

Morales-Arce et al. (2019) [33] |

|||

|

Cholula |

12 |

42 |

42 |

16 |

0 |

240–1400 CE |

Classic–Postclassic |

State of Puebla, Mexico |

||||

|

9 |

GD and HVRI |

No |

No |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1100–1500 CE |

Postclassic |

Juárez Martín (2002) [44] |

||

HVR1—Hypervariable Region 1 (or a segment); HVR2—Hypervariable Region 2 (or a segment); GD—general diagnostics of mtDNA haplogroup variants in the control and/or coding regions (restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analyses, sometimes followed by Sanger sequencing); HRM—haplogroup characterisation by high resolution melting analysis; WMG—whole mitogenome. *Some individuals.

HVR1—Hypervariable Region 1 (or a segment); HVR2—Hypervariable Region 2 (or a segment); GD—general diagnostics of mtDNA haplogroup variants in the control and/or coding regions (restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analyses, sometimes followed by Sanger sequencing); HRM—haplogroup characterisation by high resolution melting analysis; WMG—whole mitogenome. *Some individuals.

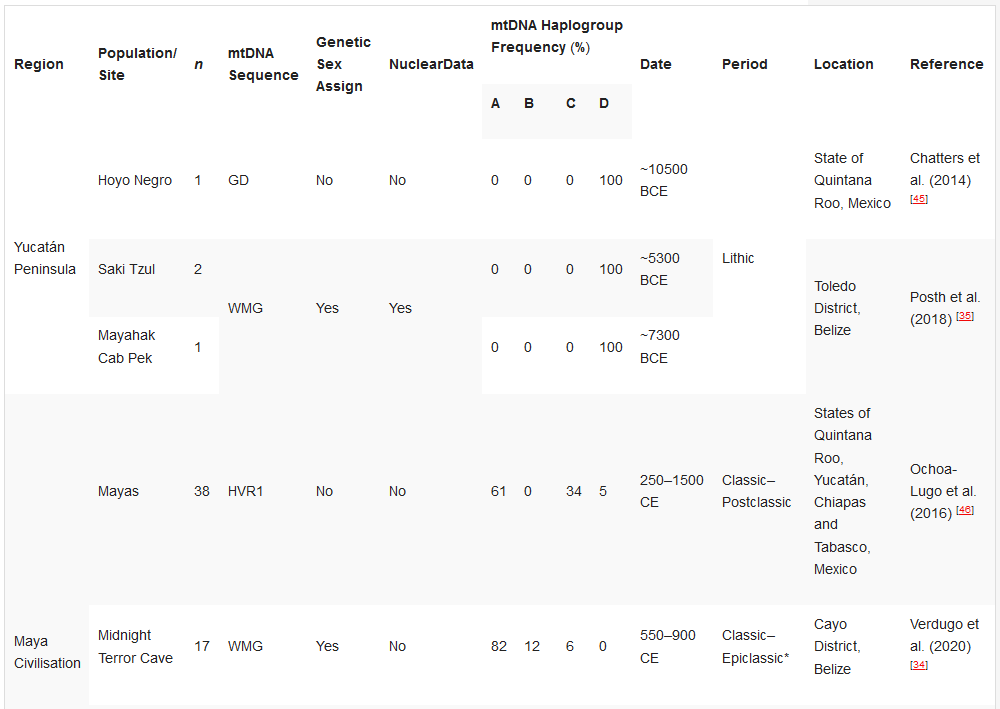

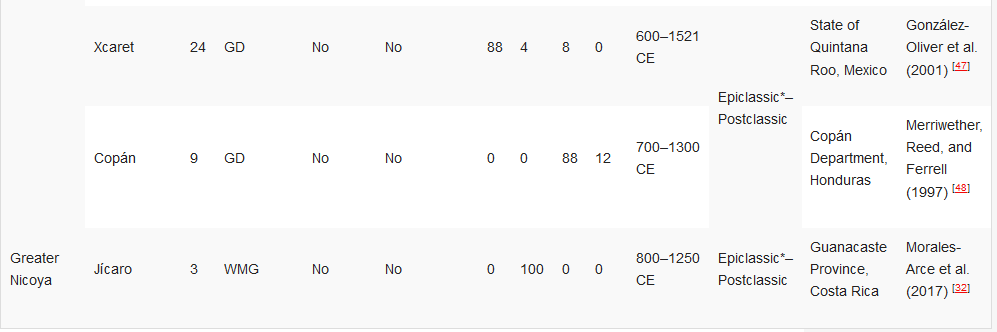

Table 23. Ancient DNA studies in the Yucatán Peninsula, Maya Civilisation, and Greater Nicoya.[32][34][35][45][46][47][48]

Ancient DNA studies in the Yucatán Peninsula, Maya Civilisation, and Greater Nicoya.

|

Region |

Population/ Site |

n |

mtDNA Sequence |

Genetic Sex Assign |

NuclearData |

mtDNA Haplogroup Frequency (%) |

Date |

Period |

Location |

Reference |

|||

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

||||||||||

|

Yucatán Peninsula |

Hoyo Negro |

1 |

GD |

No |

No |

0 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

~10500 BCE |

Lithic |

State of Quintana Roo, Mexico |

Chatters et al. (2014) [45] |

|

Saki Tzul |

2 |

WMG |

Yes |

Yes |

0 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

~5300 BCE |

Toledo District, Belize |

Posth et al. (2018) [35] |

||

|

Mayahak Cab Pek |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

~7300 BCE |

|||||||

|

Maya Civilisation |

Mayas |

38 |

HVR1 |

No |

No |

61 |

0 |

34 |

5 |

250–1500 CE |

Classic– Postclassic |

States of Quintana Roo, Yucatán, Chiapas and Tabasco, Mexico |

Ochoa-Lugo et al. (2016) [46] |

|

Midnight Terror Cave |

17 |

WMG |

Yes |

No |

82 |

12 |

6 |

0 |

550–900 CE |

Classic– Epiclassic* |

Cayo District, Belize |

Verdugo et al. (2020) [34] |

|

|

Xcaret |

24 |

GD |

No |

No |

88 |

4 |

8 |

0 |

600–1521 CE |

Epiclassic*–Postclassic |

State of Quintana Roo, Mexico |

González-Oliver et al. (2001) [47] |

|

|

Copán |

9 |

GD |

No |

No |

0 |

0 |

88 |

12 |

700–1300 CE |

Copán Department, Honduras |

Merriwether, Reed, and Ferrell (1997) [48] |

||

|

Greater Nicoya |

Jícaro |

3 |

WMG |

No |

No |

0 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

800–1250 CE |

Epiclassic*–Postclassic |

Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica |

Morales-Arce et al. (2017) [32] |

HVR1—Hypervariable Region 1 (or a segment); GD—general diagnostics of mtDNA haplogroup variants in the control and/or coding regions (restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analyses, sometimes followed by Sanger sequencing); WMG—whole mitogenome. * The Epiclassic is also known as Late Classic in parts of Mesoamerica.

HVR1—Hypervariable Region 1 (or a segment); GD—general diagnostics of mtDNA haplogroup variants in the control and/or coding regions (restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analyses, sometimes followed by Sanger sequencing); WMG—whole mitogenome. * The Epiclassic is also known as Late Classic in parts of Mesoamerica.

Interestingly, existing aDNA data come from the Central and Southeast areas of Mesoamerica, corresponding to the Basin of Mexico and the Yucatán Peninsula and its nearby territories, respectively. Nonetheless, it should be noted that Mesoamerica contains other regions with extensive archaeological and anthropological records that have not been investigated in aDNA studies yet. These regions include the Gulf Coast and Oaxaca. The Gulf Coast was initially peopled by the Olmecs (the earliest known major Mesoamerican civilisation) and was later home to the city of El Tajín. Oaxaca comprises the current Mexican state of Oaxaca as well as the border regions of Guerrero, Puebla, and Veracruz. It was home to the Mixtec and Zapotec civilisations, the Preclassic–Classic city of Monte Albán being the most important archaeological site. In contrast, the northern and western regions of Mesoamerica are largely understudied from an archaeological and anthropological perspective and have been severely looted. The North was the transition area between Mesoamerica and Aridoamerica inhabited by both hunter-gatherers and farmers and it was nearly abandoned during the Postclassic period. The West was a geographically diverse area that led to the rise of highly diverse societies characterised by the shaft tomb tradition in the Preclassic and Classic periods and the Tarascan state during the Postclassic

[49].

.

References

- González-Sobrino, B.Z.; Pintado-Cortina, A.P.; Sebastián-Medina, L.; Morales-Mandujano, F.; Contreras, A.V.; Aguilar, Y.E.; Chávez-Benavides, J.; Carrillo-Rodríguez, A.; Silva-Zolezzi, I.; Medrano-González, L. Genetic diversity and differentiation in urban and indigenous populations of mexico: Patterns of mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome lineages. Biodemogr. Soc. Biol. 2016, 62, 53–72.

- Torroni, A.; Schurr, T.G.; Cabell, M.F.; Brown, M.D.; Neel, J.V.; Larsen, M.; Smith, D.G.; Vullo, C.M.; Wallace, D.C. Asian affinities and continental radiation of the four founding Native American mtDNAs. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1993, 53, 563–590.

- Söchtig, J.; Álvarez-Iglesias, V.; Mosquera-Miguel, A.; Gelabert-Besada, M.; Gómez-Carballa, A.; Salas, A. Genomic insights on the ethno-history of the Maya and the “Ladinos” from Guatemala. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, doi:10.1186/s12864-015-1339-1.

- Green, L.D.; Derr, J.N.; Knight, A. mtDNA affinities of the peoples of north-central Mexico. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000, 66, 989–998, doi:10.1086/302801.

- Perego, U.A.; Achilli, A.; Angerhofer, N.; Accetturo, M.; Pala, M.; Olivieri, A.; Kashani, B.H.; Ritchie, K.H.; Scozzari, R.; Kong, Q.P.; et al. Distinctive paleo-indian migration routes from beringia marked by two rare mtDNA haplogroups. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 1–8.

- Sandoval, K.; Buentello-Malo, L.; Peñaloza-Espinosa, R.; Avelino, H.; Salas, A.; Calafell, F.; Comas, D. Linguistic and maternal genetic diversity are not correlated in Native Mexicans. Hum. Genet. 2009, 126, 521–531.

- Guardado-Estrada, M.; Juarez-Torres, E.; Medina-Martinez, I.; Wegier, A.; MacÍas, A.; Gomez, G.; Cruz-Talonia, F.; Roman-Bassaure, E.; Piñero, D.; Kofman-Alfaro, S.; et al. A great diversity of Amerindian mitochondrial DNA ancestry is present in the Mexican mestizo population. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 54, 695–705.

- Kemp, B.M.; Gonzalez-Oliver, A.; Malhi, R.S.; Monroe, C.; Schroeder, K.B.; McDonough, J.; Rhett, G.; Resendez, A.; Penaloza-Espinosa, R.I.; Buentello-Malo, L.; et al. Evaluating the farming/language dispersal hypothesis with genetic variation exhibited by populations in the southwest and Mesoamerica. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6759–6764, doi:10.1073/pnas.0905753107.

- Gorostiza, A.; Acunha-Alonzo, V.; Regalado-Liu, L.; Tirado, S.; Granados, J.; Sámano, D.; Rangel-Villalobos, H.; González-Martín, A. Reconstructing the history of mesoamerican populations through the study of the mitochondrial DNA control region. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44666.

- Mizuno, F.; Gojobori, J.; Wang, L.; Onishi, K.; Sugiyama, S.; Granados, J.; Gomez-Trejo, C.; Acuña-Alonzo, V.; Ueda, S. Complete mitogenome analysis of indigenous populations in Mexico: Its relevance for the origin of Mesoamericans. J. Hum. Genet. 2014, 59, 359–367.

- González-Martín, A.; Gorostiza, A.; Regalado-Liu, L.; Arroyo-Peña, S.; Tirado, S.; Nuño-Arana, I.; Rubi-Castellanos, R.; Sandoval, K.; Coble, M.D.; Rangel-Villalobos, H. Demographic history of indigenous populations in Mesoamerica based on mtDNA sequence data. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131791.

- Páez-Riberos, L.A.; Muñoz-Valle, J.F.; Figuera, L.E.; Nuño-Arana, I.; Sandoval-Ramírez, L.; González-Martín, A.; Ibarra, B.; Rangel-Villalobos, H. Y-linked haplotypes in Amerindian chromosomes from Mexican populations: Genetic evidence to the dual origin of the Huichol tribe. Leg. Med. 2006, 8, 220–225.

- Sandoval, K.; Moreno-Estrada, A.; Mendizabal, I.; Underhill, P.A.; Lopez-Valenzuela, M.; Peñaloza-Espinosa, R.; Lopez-Lopez, M.; Buentello-Malo, L.; Avelino, H.; Calafell, F.; et al. Y-chromosome diversity in native Mexicans reveals continental transition of genetic structure in the Americas. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2012, 148, 395–405.

- Perez-Benedico, D.; La Salvia, J.; Zeng, Z.; Herrera, G.A.; Garcia-Bertrand, R.; Herrera, R.J. Mayans: A y chromosome perspective. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 24, 1352–1358, doi:10.1038/ejhg.2016.18.

- Silva-Zolezzi, I.; Hidalgo-Miranda, A.; Estrada-Gil, J.; Fernandez-Lopez, J.C.; Uribe-Figueroa, L.; Contreras, A.; Balam-Ortiz, E.; Del Bosque-Plata, L.; Velazquez-Fernandez, D.; Lara, C.; et al. Analysis of genomic diversity in Mexican Mestizo populations to develop genomic medicine in Mexico. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 8611–8616.

- Moreno-Estrada, A.; Gignoux, C.R.; Fernández-López, J.C.; Zakharia, F.; Sikora, M.; Contreras, A.V.; Acuña-Alonzo, V.; Sandoval, K.; Eng, C.; Romero-Hidalgo, S.; et al. The genetics of Mexico recapitulates Native American substructure and affects biomedical traits. Science 2014, 344, 1280–1285.

- Ávila-Arcos, M.C.; McManus, K.F.; Sandoval, K.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J.E.; Martin, A.R.; Luisi, P.; Villa-Islas, V.; Peñaloza-Espinosa, R.I.; Eng, C.; Huntsman, S.; et al. Population history and gene divergence in Native Mexicans inferred from 76 human exomes. bioRxiv 2019, 534818, doi:10.1101/534818.

- Bustamante, C.D.; De La Vega, F.M.; Burchard, E.G. Genomics for the world. Nature 2011, 475, 163–165, doi:10.1038/475163a.

- Sirugo, G.; Williams, S.M.; Tishkoff, S.A. The missing diversity in human genetic studies. Cell 2019, 177, 26–31, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.048.

- Tsosie, K.S.; Begay, R.L.; Fox, K.; Garrison, N.A. Generations of genomes: Advances in paleogenomics technology and engagement for Indigenous people of the Americas. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2020, 62, 91–96, doi:10.1016/j.gde.2020.06.010.

- Anderson, S.; Bankier, A.T.; Barrell, B.G.; de Bruijn, M.H.L.; Coulson, A.R.; Drouin, J.; Eperon, I.C.; Nierlich, D.P.; Roe, B.A.; Sanger, F.; et al. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature 1981, 290, 457–465.

- Giles, R.E.; Blanc, H.; Cann, H.M.; Wallace, D.C. Maternal inheritance of human mitochondrial DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1980, 77, 6715–6719.

- Sigurðardóttir, S.; Helgason, A.; Gulcher, J.R.; Stefansson, K.; Donnelly, P. The mutation rate in the human mtDNA control region. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000, 66, 1599–1609.

- Andrews, R.M.; Kubacka, I.; Chinnery, P.F.; Lightowlers, R.N.; Turnbull, D.M.; Howell, N. Reanalysis and revision of the cambridge reference sequence for human mitochondrial DNA. Nat. Genet. 1999, 23, 147, doi:10.1038/13779.

- Behar, D.M.; van Oven, M.; Rosset, S.; Metspalu, M.; Loogväli, E.-L.; Silva, N.M.; Kivisild, T.; Torroni, A.; Villems, R. A ‘copernican’ reassessment of the human mitochondrial DNA tree from its root. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 90, 675–684, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.002.

- van Oven, M.; Kayser, M. Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation. Hum. Mutat. 2009, 30, 386–394.

- Krings, M.; Stone, A.C.; Schmitz, R.W.; Krainitzki, H.; Stoneking, M.; Paabo, S. Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of modern humans. Cell 1997, 90, 19–30.

- Llamas, B.; Willerslev, E.; Orlando, L.; Orlando, L. Human evolution: A tale from ancient genomes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0484.

- Tamm, E.; Kivisild, T.; Reidla, M.; Metspalu, M.; Smith, D.G.; Mulligan, C.J.; Bravi, C.M.; Rickards, O.; Martinez-Labarga, C.; Khusnutdinova, E.K.; et al. Beringian standstill and spread of native American founders. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e829.

- Perego, U.A.; Angerhofer, N.; Pala, M.; Olivieri, A.; Lancioni, H.; Kashani, B.H.; Carossa, V.; Ekins, J.E.; Gómez-Carballa, A.; Huber, G.; et al. The initial peopling of the Americas: A growing number of founding mitochondrial genomes from Beringia. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1174–1179.

- Llamas, B.; Fehren-Schmitz, L.; Valverde, G.; Soubrier, J.; Mallick, S.; Rohland, N.; Nordenfelt, S.; Valdiosera, C.; Richards, S.M.; Rohrlach, A.; et al. Ancient mitochondrial DNA provides high-resolution time scale of the peopling of the Americas. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501385.

- Morales-Arce, A.Y.; Hofman, C.A.; Duggan, A.T.; Benfer, A.K.; Katzenberg, M.A.; McCafferty, G.; Warinner, C. Successful reconstruction of whole mitochondrial genomes from ancient Central America and Mexico. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 18100.

- Morales-Arce, A.Y.; McCafferty, G.; Hand, J.; Schmill, N.; McGrath, K.; Speller, C. Ancient mitochondrial DNA and population dynamics in postclassic Central Mexico: Tlatelolco (AD 1325–1520) and Cholula (AD 900–1350). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2019, 11, 3459–3475.

- Verdugo, C.; Zhu, K.; Kassadjikova, K.; Berg, L.; Forst, J.; Galloway, A.; Brady, J.E.; Fehren-Schmitz, L. An investigation of ancient Maya intentional dental modification practices at Midnight Terror Cave using anthroposcopic and paleogenomic methods. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2020, 115, 105096, doi:10.1016/j.jas.2020.105096.

- Posth, C.; Nakatsuka, N.; Lazaridis, I.; Skoglund, P.; Mallick, S.; Lamnidis, T.C.; Rohland, N.; Nägele, K.; Adamski, N.; Bertolini, E.; et al. Reconstructing the deep population history of central and South America. Cell 2018, 175, 1185–1197, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.027.

- Salazar, A.H. Estudio Genético Poblacional de Restos Óseos Prehispánicos de Una Subpoblación de Teotihuacan; CINVESTAV: México City, Mexico, 2007.

- Aguirre-Samudio, A.J.; González-Sobrino, B.Z.; Álvarez-Sandoval, B.A.; Montiel, R.; Serrano-Sánchez, C.; Meza-Peñaloza, A. Genetic history of classic period Teotihuacan burials in Central Mexico. Rev. Argent. Antropol. Biol. 2017, 19, 1–14.

- Álvarez-Sandoval, B.A.; Manzanilla, L.R.; Montiel, R. Sex determination in highly fragmented human DNA by High-Resolution Melting (HRM) analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104629.

- Álvarez-Sandoval, B.A.; Manzanilla, L.R.; González-Ruiz, M.; Malgosa, A.; Montiel, R. Genetic evidence supports the multiethnic character of teopancazco, a neighborhood center of teotihuacan, Mexico (ad 200–600). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132371.

- Mata-Míguez, J.; Overholtzer, L.; Rodríguez-Alegría, E.; Kemp, B.M.; Bolnick, D.A. The genetic impact of Aztec imperialism: Ancient mitochondrial DNA evidence from Xaltocan, Mexico. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2012, 149, 504–516.

- Kemp, B.M.; Resendéz, A.; Román Berrelleza, J.A.; Malhi, R.; Smith, D.G. An analysis of ancient Aztec mtDNA from Tlatelolco: Pre-Columbian relations and the spread of Uto-Aztecan. In Biomolecular Archaeology: Genetic Approaches to the Past; Reed, D.M., Ed.; Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University, 2005, 22–46.

- Navarro, E.S. De La Mesoamérica Prehispanica a la Colonial: La Huella del DNA Antiguo; Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2006.

- De La Cruz, I.; González-Oliver, A.; Kemp, B.M.; Román, J.A.; Smith, D.G.; Torre-Blanco, A. Sex identification of children sacrificed to the ancient Aztec rain gods in Tlatelolco. Curr. Anthropol. 2008, 49, 519–526.

- Martín, A.I.J. Parentesco Biológico Entre los Pobladores Prehispánicos de Cholula, Mediante el Análisis Molecular de Sus Restos Óseos; Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2002.

- Chatters, J.C.; Kennett, D.J.; Asmerom, Y.; Kemp, B.M.; Polyak, V.; Lberto N.B.; Beddows, P.A.; Reinhardt, E.; Arroyo-Cabrales, J.; Bolnick, D.A.; et al. Late pleistocene human skeleton and mtDNA link paleoamericans and modern native Americans. Science 2014, 344, 750–755, doi:10.1126/science.1252619.

- Ochoa-Lugo, M.I.; de Muñoz, M.L.; Pérez-Ramírez, G.; Beaty, K.G.; López-Armenta, M.; Cervini-Silva, J.; Moreno-Galeana, M.; Meza, A.M.; Ramos, E.; Crawford, M.H.; et al. Genetic affiliation of pre-hispanic and contemporary Mayas through maternal linage. Hum. Biol. 2016, 88, 136–167.

- González-Oliver, A.; Márquez-Morfín, L.; Jiménez, J.C.; Torre-Blanco, A. Founding amerindian mitochondrial DNA lineages in ancient Maya from Xcaret, Quintana Roo. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2001, 116, 230–235.

- Merriwether, D.A.; Reed, D.M.; Ferrell, R.E. Ancient and contemporary Mitochondrial DNA variation in the Maya. In Bones of the Maya: Studies of Ancient Skeletons; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; pp. 208–217, ISBN 0817353763.

- López-Austin, A.; López-Luján, L. El Pasado Indígena; El Colegio de México, Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City, Mexico, 1996; ISBN 978-607-16-2136-8.

- Salazar, A.H. Estudio Genético Poblacional de Restos Óseos Prehispánicos de Una Subpoblación de Teotihuacan; CINVESTAV: México City, Mexico, 2007.

- Aguirre-Samudio, A.J.; González-Sobrino, B.Z.; Álvarez-Sandoval, B.A.; Montiel, R.; Serrano-Sánchez, C.; Meza-Peñaloza, A. Genetic history of classic period Teotihuacan burials in Central Mexico. Rev. Argent. Antropol. Biol. 2017, 19, 1–14.

- Álvarez-Sandoval, B.A.; Manzanilla, L.R.; Montiel, R. Sex determination in highly fragmented human DNA by High-Resolution Melting (HRM) analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104629.

- Álvarez-Sandoval, B.A.; Manzanilla, L.R.; González-Ruiz, M.; Malgosa, A.; Montiel, R. Genetic evidence supports the multiethnic character of teopancazco, a neighborhood center of teotihuacan, Mexico (ad 200–600). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132371.

- Mata-Míguez, J.; Overholtzer, L.; Rodríguez-Alegría, E.; Kemp, B.M.; Bolnick, D.A. The genetic impact of Aztec imperialism: Ancient mitochondrial DNA evidence from Xaltocan, Mexico. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2012, 149, 504–516.

- Kemp, B.M.; Resendéz, A.; Román Berrelleza, J.A.; Malhi, R.; Smith, D.G. An analysis of ancient Aztec mtDNA from Tlatelolco: Pre-Columbian relations and the spread of Uto-Aztecan. In Biomolecular Archaeology: Genetic Approaches to the Past; Reed, D.M., Ed.; Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University, 2005, 22–46.

- Navarro, E.S. De La Mesoamérica Prehispanica a la Colonial: La Huella del DNA Antiguo; Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2006.

- De La Cruz, I.; González-Oliver, A.; Kemp, B.M.; Román, J.A.; Smith, D.G.; Torre-Blanco, A. Sex identification of children sacrificed to the ancient Aztec rain gods in Tlatelolco. Curr. Anthropol. 2008, 49, 519–526.

- Martín, A.I.J. Parentesco Biológico Entre los Pobladores Prehispánicos de Cholula, Mediante el Análisis Molecular de Sus Restos Óseos; Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2002.

- Chatters, J.C.; Kennett, D.J.; Asmerom, Y.; Kemp, B.M.; Polyak, V.; Lberto N.B.; Beddows, P.A.; Reinhardt, E.; Arroyo-Cabrales, J.; Bolnick, D.A.; et al. Late pleistocene human skeleton and mtDNA link paleoamericans and modern native Americans. Science 2014, 344, 750–755, doi:10.1126/science.1252619.

- Ochoa-Lugo, M.I.; de Muñoz, M.L.; Pérez-Ramírez, G.; Beaty, K.G.; López-Armenta, M.; Cervini-Silva, J.; Moreno-Galeana, M.; Meza, A.M.; Ramos, E.; Crawford, M.H.; et al. Genetic affiliation of pre-hispanic and contemporary Mayas through maternal linage. Hum. Biol. 2016, 88, 136–167.

- González-Oliver, A.; Márquez-Morfín, L.; Jiménez, J.C.; Torre-Blanco, A. Founding amerindian mitochondrial DNA lineages in ancient Maya from Xcaret, Quintana Roo. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2001, 116, 230–235.

- Merriwether, D.A.; Reed, D.M.; Ferrell, R.E. Ancient and contemporary Mitochondrial DNA variation in the Maya. In Bones of the Maya: Studies of Ancient Skeletons; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; pp. 208–217, ISBN 0817353763.

- Mizuno, F.; Kumagai, M.; Kurosaki, K.; Hayashi, M.; Sugiyama, S.; Ueda, S.; Wang, L. Imputation approach for deducing a complete mitogenome sequence from low-depth-coverage next-generation sequencing data: Application to ancient remains from the Moon Pyramid, Mexico. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 62, 631–635.

- Manzanilla, L.R. Multiethnicity and Migration at Teopancazco; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2017; ISBN 9780813054285.

- Plunket, P.; Uruñuela, G. Preclassic household patterns preserved under volcanic ash at Tetimpa, Puebla, Mexico. Lat. Am. Antiq. 1998, 9, 287–309.

- Cowgill, G.L. State and society at Teotihuacan, Mexico. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1997, 26, 129–161, doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.26.1.129.

- Froese, T.; Gershenson, C.; Manzanilla, L.R. Can government be self-organized? A mathematical model of the collective social organization of ancient Teotihuacan, Central Mexico. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109966.

- Siebe, C. Age and archaeological implications of Xitle volcano, southwestern Basin of Mexico-City. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2000, 104, 45–64, doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(00)00199-2.

- Appel, G.I.M. Elementos traza aplicados al análisis de la paleodieta en Teopancazco. In Estudios Arqueométricos del Centro de Barrio de Teopancazco en Teotihuacan; Manzanilla, L.R., Ed.; Coordinación de Humanidades–Coordinación de la Investigación Científica, UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico; 2012; pp. 325–345.

- Puente, P.M.; Alvarado, E.C.; Naim, L.R.M.; Trujano, F.J.O. Estudio de la paleodieta empleando isótopos estables de los elementos carbono, oxígeno y nitrógeno en restos humanos y de fauna encontrados en el barrio teotihuacano de Teopancazco. In Estudios Arqueométricos del Centro de Barrio de Teopancazco en Teotihuacan; Manzanilla, L.R., Ed.; Coordinación de Humanidades–Coordinación de la Investigación Científica, UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012; pp. 347–423.

- Schaaf, P.; Solís, G.; Manzanilla, L.R.; Hernández, T.; Lailson, B.; Horn, P. Isótopos de estroncio aplicados a estudios de migración humana en el centro de barrio de Teopancazco, Teotihuacan. In Estudios Arqueométricos del Centro de Barrio de Teopancazco en Teotihuacan; Manzanilla, L.R., Ed.; Coordinación de Humanidades–Coordinación de la Investigación Científica, UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012; pp. 425–448.

- Hassig, R. War and Society in Ancient Mesoamerica; University of California: Oakland, CA, USA, 1992.

- Carballo, D.M. Effigy vessels, religious integration, and the origins of the central Mexican pantheon. Anc. Mesoam. 2007, 18, 53–67, doi:10.1017/S0956536107000028.

- Lachniet, M.S.; Bernal, J.P.; Asmerom, Y.; Polyak, V.; Piperno, D. A 2400 yr Mesoamerican rainfall reconstruction links climate and cultural change. Geology 2012, 40, 259–262, doi:10.1130/G32471.1.

- Acuna-Soto, R.; Stahle, D.W.; Therrell, M.D.; Chavez, S.G.; Cleaveland, M.K. Drought, epidemic disease, and the fall of classic period cultures in Mesoamerica (AD 750-950). Hemorrhagic fevers as a cause of massive population loss. Med. Hypotheses 2005, 65, 405–409.

- Acuna-Soto, R.; Stahle, D.W.; Cleaveland, M.K.; Therrell, M.D. Megadrought and megadeath in 16th century Mexico. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 360–362, doi:10.3201/eid0804.010175.

- Kubler, G. La traza colonial de Cholula. Estud. Hist. Novohisp. 1968, 2, 1–30, doi:10.22201/iih.24486922e.1968.002.3217.

- Brumfiel, E.M. Aztec state making: Ecology, structure, and the origin of the state. Am. Anthropol. 1983, 85, 261–284, doi:10.1525/aa.1983.85.2.02a00010.

- Gibson, C. The Aztecs under Spanish Rule: A History of the Indians of the Valley of Mexico, 1519–1810; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 1964.

- Hicks, F. Xaltocan under Mexican Domination, 1435–1520; Caciques their people; Marcus, J., Zeitlin, J.F., Eds.; Museum Anthropology, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994; pp. 67–85.

- Overholtzer, L. Otomies at Xaltocan: A case of ethnic change. In Proceedings of the 76th Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, Sacramento, CA, USA, 30 March–3 April 2011.

- Kemp, B.M.; Lindo, J.; Bolnick, D.A.; Malhi, R.S.; Chatters, J.C. Response to comment on “late pleistocene human skeleton and mtDNA link paleoamericans and modern native Americans.” Science 2015, 347, 835, doi: 10.1126/science.1261188.

- Prüfer, K.; Meyer, M. Comment on “late pleistocene human skeleton and mtDNA link paleoamericans and modern native Americans.” Science 2015, 347, 835, doi:10.1126/science.1260617.

- Rasmussen, M.; Anzick, S.L.; Waters, M.R.; Skoglund, P.; Degiorgio, M.; Stafford, T.W.; Rasmussen, S.; Moltke, I.; Albrechtsen, A.; Doyle, S.M.; et al. The genome of a late Pleistocene human from a Clovis burial site in western Montana. Nature 2014, 506, 225–229.

- Wade, L. The arrival of strangers. Science 2020, 367, 968–973, doi:10.1126/science.367.6481.968.

- Lalueza, C.; Pérez-Pérez, A.; Prats, E.; Cornudella, L.; Turbón, D. Lack of founding Amerindian mitochondrial DNA lineages in extinct Aborigines from Tierra del Fuego–Patagonia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1997, 6, 41–46.

- Starikovskaya, Y.B.; Sukernik, R.I.; Schurr, T.G.; Kogelnik, A.M.; Wallace, D.C. mtDNA diversity in Chukchi and Siberian Eskimos: Implications for the genetic history of ancient Beringia and the peopling of the New World. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998, 63, 1473–1491, doi:10.1086/302087.

- McCafferty, G.; Dennett, C. Ethnogenesis and hybridity in Proto-historic Nicaragua. Archaeol. Rev. Camb. 2013, 28, 191–215.

- Umaña, A.C.; Rojas, E.I. Mapa de la distribución territorial aproximada de las lenguas indígenas habladas en Costa Rica y en sectores colindantes de Nicaragua y de Panamá en el siglo XVI. Estud. Linguist. Chibcha 2009, XXVIII, 109–112.

- Ioannidis, A.G.; Blanco-Portillo, J.; Sandoval, K.; Hagelberg, E.; Miquel-Poblete, J.F.; Moreno-Mayar, J.V.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J.E.; Quinto-Cortés, C.D.; Auckland, K.; Parks, T.; et al. Native American gene flow into Polynesia predating Easter Island settlement. Nature 2020, 583, 572–577, doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2487-2.