Chagas disease is a complex zoonosis. Its natural history involves the interaction of transmitting arthropods with wild, peridomestic, and domestic mammals, and it has a great diversity of transmission forms. In a vertebrate host, the disease has two clinical phases: an acute phase and a chronic one; the former evolves without demonstrated pathology and can last 10–20 years. After this phase, some patients progress to the chronic symptomatic phase, in which they develop mainly cardiac lesions. The lesions in this cardiomyopathy involve several cardiac tissues, mainly the myocardium, and in severe cases, the endocardium pericardium; this can cause pleural effusion, which may evolve into sudden death, which is more frequent in cases with dilated heart disease and severe heart failure.

1. Introduction

Chagas disease is a complex zoonosis. Its natural history involves the interaction of transmitting arthropods with wild, peridomestic, and domestic mammals, and it has a great diversity of transmission forms. In a vertebrate host, the disease evolution is evinced by various clinical manifestations [

1,

2].

The disease is caused by

Trypanosoma cruzi, a flagellated protozoan that is naturally transmitted by hematophagous Hemiptera insects (triatomines). The parasite was discovered in 1909 by Dr. Carlos Chagas in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Dr. Chagas also described a large part of the biological cycle, linking the parasite to the transmitting triatomine (

Panstrongylus megistus). He was able to isolate the parasite and replicated the infection in experimental animals. Dr. Chagas also mentioned that rural housing conditions, which to date have not changed significantly in endemic countries, are important for the spread of the vector. As a clinical entity, Chagas disease is linked to poverty [

1].

Chagas disease is endemic in 21 countries within continental Latin America. It is distributed from the south of the United States, in Central America, the Southern Cone, Andean countries, and Amazonian countries. In the Americas, 30,000 new cases are reported every year, 12,000 deaths on average, and 8600 newborns are infected at gestation. In 2019, a prevalence rate of 933.76 per 100,000 population was recorded. Currently, about 70 million people in the Americas live in areas at risk for the infection [

3]. Humans become infected with

T. cruzi by several mechanisms. The most important one is natural transmission, involving an infected triatomine bug.

T4].Ch

iagas

transmission form is very common in rural areas, where housing traits and the ecotope favor a colonization of the domestic niche by insects. The second transmission form, restricted to urban areas, is related to the transfusion of blood or its components. This transmission form depends on the migration of rural population to cities, as more than 70% of the population in some cities had immigrated from high-prevalence areas of the disease [4].

Tdisease has two clinical phases: an acute phase and a chronic one. Most cases of acute Chagas disease are asymptomatic; only 5–10% of infected subjects develop symptoms, including persistent fever, asthenia, adynamia, headache, and hepatosple-nomegaly, all of which are nonspecific. Among these symptomatic individuals, the most frequent pathognomonic signs are the Romaña sign, characterized by unilateral bi-palpebral edema, whe primary vectors for Chagas Disease are Triatoma infestansch is observed in Argentina,50% Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Peru; Rhodnius prolixus of cases, and the indurated cutaneous chagoma, found in C25% olombia, Vf cases.

Be

nzn

ezuela, and Central America;idazole and nifurtimox are the T. dimidiata ion

ly Ecuador and Central America; and R. pallescens drugs with proven efficacy again

st Panama [3]Chagas disease.

In Both

e Americas, natural infection is associated with risk factors such as housing construction material and other characteristics that favor the coloniz drugs have been approved internationally. Antiparasitic treatment of these cardiomyopathies is accompanied by the administration of antiarrhythmics and pace-maker placement. In the most severe cases, heart transplantation

of human dwellings in rural areacan be required [5,7].

2. Pathogenic Mechanisms of Immune Response Evasion in Chagas Disease

Mos

.t For this reason, it is considered as a neglected tropical disease [4]. PAHO/WHO, workof the mechanisms involved in evading

with

the endemic countries, have launched several Subregional Disease Prevention and Control Initiatives. These include the improvement of housing to halt vectorial transmission in 17 countries, and screening of blood donors in the 21 endemic countriese immune response occur in the acute phase, when trypomastigotes establish contact with immune cells of the vertebrate host. The parasite has evolved mechanisms to survive processes such as phagocytosis and the complement system, in addition to

eliminating some vector species such as R. prolixus interfering with lymphocyte maturati

on

El Salvador, Costa Rica, and Mexico, and T. infestans . When metacyclic trypomastigotes contact host cells, ei

n Bther

azil and Uruguay [3,5].

Due to t through

e increase in population mobility worldwide, Chagas diseaskin lesions or mucous membranes, the immune response is

consideredactivated. aT. cruzi majoenter

health problem, which has reached countries where vector transmission does not exist, dues cells through two main mechanisms. The first one is lysosome-dependent, which favors Ca2+ tmo

the immigratiobilization [18]. In

ofthis s

eropositive cases from endemic geographic areas. This poses a risk of transmission through transfusions, organ and tissue transplants, and even maternal-fetal transmission in the USA, Canada, and some European and Western Pacific countries. It has been estimated that Spain istage, the parasite surface glycoprotein gp82 is crucial for cell adhesion and lysosomal fusion at the site of entry. Cruzipain has also been proven to be critical for calcium induction and lysosome recruitment. It is a cysteine-protease secreted by trypomastigotes [19,20]. tThe

main non-endemic country in the number of transmissions,second mechanism involves invagination of the plasma membrane followed by

the USA and Italy [6].

Chaga lys

dios

ease has two clinical phases: an acute phase and a chronic one. Most cases of acute Chagas disease are asymptomatic; only 5–10% of infected subjects develop symptoms, including persistent fever, asthenia, adynamia, headache, and hepatosple-nomegaly, all of which are nonspecific. Among these symptomatic individuals,omal fusion. The acidification process of lysosomes containing the parasite is key to its differentiation into an amastigote, which is the replicative form. A disruption of cytoskeletal actin facilitates the mo

st frequent pathognomonic signs are the Romaña sign, characterized by unilateral bi-palpebral edema, which is observed in 50% of cases, and the indurated cutaneous chagoma, found in 25% of casesbilization of lysosomes towards the cell periphery, where they will fuse with the cytoplasmic membrane and contribute to the formation of a parasitic vacuole [21].

BoAft

h signs are often accompanied by regional adeno-megaly. Ier several divisions in the parasitophorous vacuole, where sialic acid residues are added on the

rT. cruzi mem

bra

ining 25% of patients, there is no sign of portal entry, but some of the nonspecific symptoms mentioned above can be found [7]. The mne by parasitic trans-sialidases, the phagolysosome is lysed. Thus, trypomastigotes are released into the cytoplasm and bloo

dst

frequent symptom is fever, which is present in up to 95% of cases,ream to infect distant or adjacent tissues and cells [22]. usuNota

lly without specific characteristics. All other signs and symptoms, including asthenia, adynamia, headachebly, factors such as strain, the level of antioxidant enzyme expression, and

hepatosple-nomegaly, are nonspecific [3,5].the kinetics of association with the Wph

ilagolysosome

T. cruzi cma

ny in

fect any nucleated cell, some strains exhibit a marked tropism for myocardial cells, smooth muscle cells of the digestive system, or nervous tissue, among turn contribute to parasite evasion and persistence in the host. In contrast to other

cell types. Cardiac manifestations include primarily organprotozoa, which inhibit phagolysosome maturation, T. cruzi e

nlva

rgement (cardiomegaly) [7].

The de mac

hro

nic phase is divided into a chronic asymptomatic phase and a symptomatic phase; the former evolves without demonstrated patphage activity by the mechanisms mentioned above, and escape from the phagolysosome into the host cell cytoplasm, where they replicate [29].

Th

e co

logy and can last 10–20 years; however, cases have been reported in minors in Mexico where this period lasts 2–7 years before the chronic form with cardiovascular symptomatology can be detected [8]; mplement system features a specialized pathway for mannose recognition in pathogenic organisms, and it is known that blood trypomastigotes activate this

phas

e is clinically asymptomatic and exhibits very lowystem; however, the parasite

mia, so that the methods of choice for diagnosis are serological expresses a set of specific surface proteins for complement evasion [30,

31]. T. cruzi tran

d confs-si

rmation requires two positive tests with different principles [9].

Aalidases are crucial for host cell infection by transferring sialic acid f

ter

this phase, patients progresom mammalian cells to the

chronic symptomaticir own glycocalyx [32]. pTh

ase, with a proven symptomatology, in which they develop mainly cardiac lesions and, to a lesser extent, digestive lesions, mainly in the esophagus and colon, and in a few cases in the peripheral nervous system. Cardiac lesions cause alterations in myocardial contractilityeir presence is also known to reduce the recognition of anti-α-Gal antibodies in the bloodstream, in addition to evading the lytic effect of complement by promoting the conversion of C3 to inactive C3b (iC3b) [33].

T. cruzi ca

nd the electrical impulse, mainlylreticulin (TcCRT) is also involved in the

bundle of His, the particular right bundle branch block with left anterior fascicular hemiblock, ventricular extrasystoles, and atrioventricular block [3,7]evasion of the lectin pathway by binding to MBL or inhibiting the classical complement pathway by binding to C1q. The

se l

esions in this cardiomyopathy involve several cardiac tissues, mainly inks inactivate the membrane attack complex (MAC) formation pathway [34]. Anothe

r m

yocardium, and in severe cases, the endocardium pericardium; this can cause pleural effusioechanism by which the parasite controls the complement pathway is mediated by the CRP protein, which

may evolve into sudden death, which is more frequent in cases with dilated heart disease and severe heart failure [10]. Cis anchored to the parasite membrane. This 160-kDa glycoprotein binds non-covalently to C3b and C4b to inhibit the a

rssembl

os Chagas described digestive disorders linked to the disease in 1916, although Kidder and Fletcher had already done so in 1857, when they called it mal d’engasgo, i.e., “disease causing dysphagia” [11]y of C3 convertase, rendering it inactive to catalyze the cleavage of the complement system on the parasite surface.

EsAno

phageal involvement usually consists of a megaesophagus with slow esophageal transit disorders, along with pain and difficulty in swallowing. In cases of colon involvement, ather parasitic protein called T-DAF accelerates the decay of C3 and C5 convertase in the classical and alternative pathways of the complement system. [35].

3. Histopathological Mechanisms Related to Tissue Parasitism

The mprese

gacolon and constipnce and replication

are typical [12,13]. Chagas heaby binar

ty disease is clinically classified according to symptoms, and electrocardio-graphic, echfission of intracellular amastigotes in the myocardio

graphic, and radiological abnormalities, especially changes in left ventricular function. Some riskcyte and its ensuing lysis cause inflammation, the release of cellular components, and finally the destruction of cardiac tissue [36]. A fadirect

ors predisposing one to a progression to the chronic phase include electrocardiographic abnormalities correlation between the presence of the parasite and tissue inflammation has been reported [37],

maleve

sex, systolic blood pressure lessn when only the presence of T. cruzi ant

han 120 mmHg, altered systolicigens or DNA has been confirmed in chronic lesions [38]. The inf

unction, left ventricular dilatationection can affect skeletal, cardiac, and

complex arrhythmias; risk scores have been proposed to stratify the risk of death, although their clinical value is still under study [14]. Ismooth muscle, as well as neuronal tissue. Parasitism in the myocardium causes destruction a

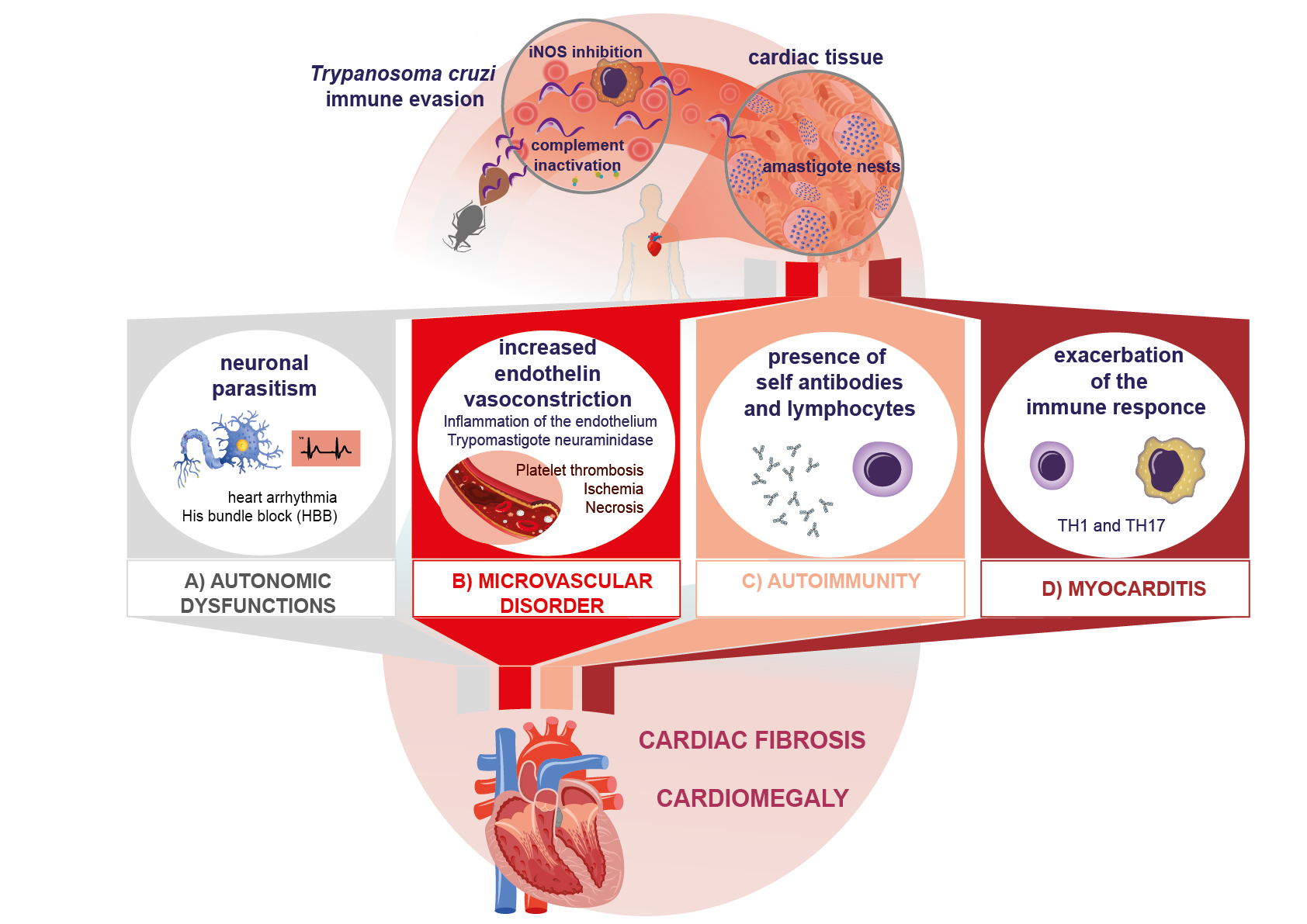

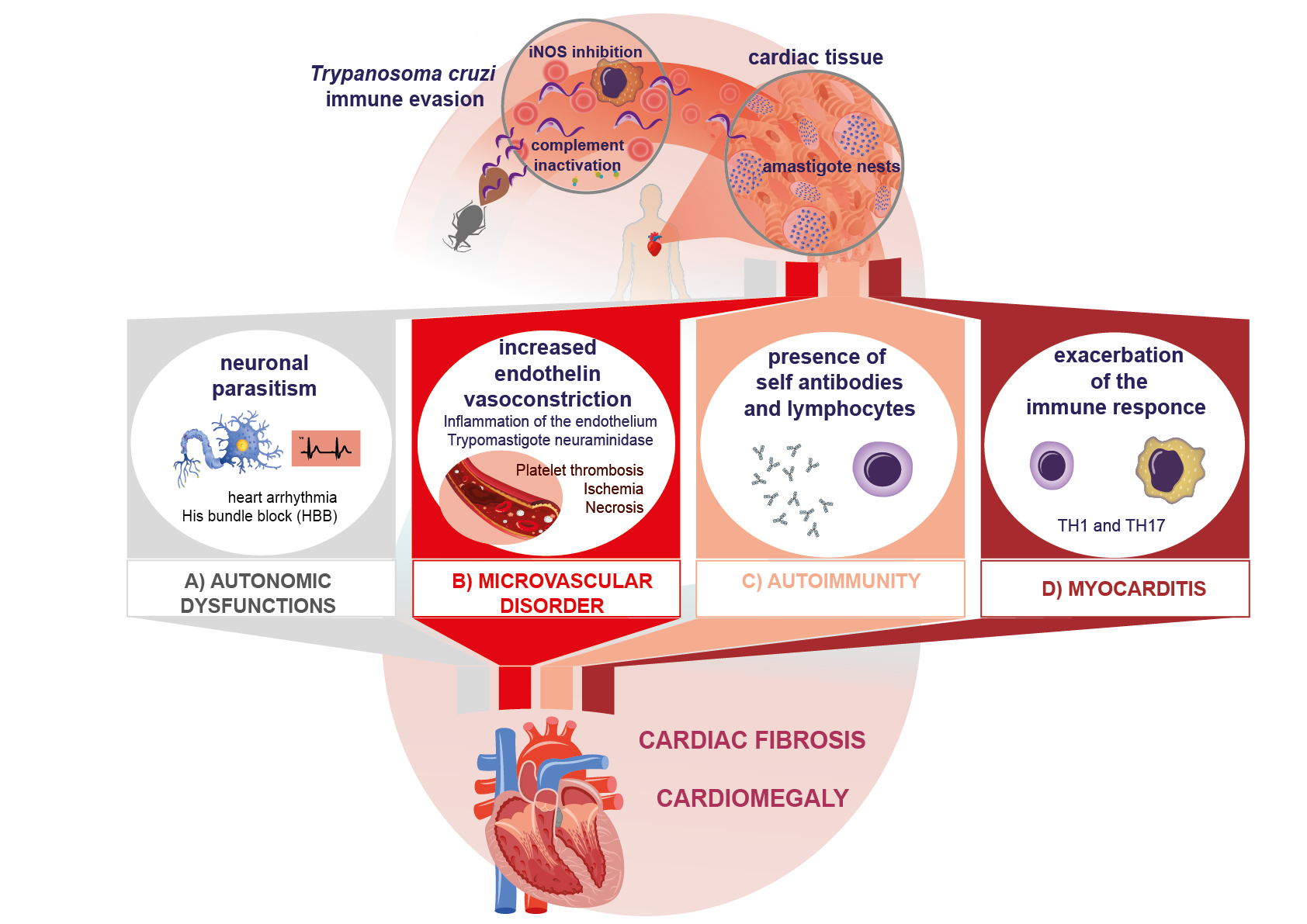

nd consensus, several authors note that the main predictors of poor prognosis in chronic Chagas disease are a deterioration of left ventricular function, falling into classes III (fatigue, palpitations, dyspnea, or anginal pain) and VI (cardiomegaly and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia) of the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classificafibrosis in the Schwann sheath and nerve fibers, which leads to neurogenic alterations, clinically expressed as arrhythmias, His bundle branch block, and even the presence of dyssynergic areas in the parietal function of

heart faithe heart (Figure 1A). All

ure [15].of Othe

r risk scores have been proposed. Rassi uses a combination of clinical symptoms, cabinet test results, and demographic datase are characteristic manifestations of the chronic phase of Chagas disease [

1639,40].

OAn

the other hand, de Sousa use a four-factor score that includeother important mechanism described in myocardial injury is the

QT dispersion interval on ECG, syncope, premature ventrioccurrence of microvascular

contractions, and left ventricular function [17].

Babnormalities caused by the increase in en

znid

azole and nifurtimox are the only drugs with proven efficacy against Chagas disease. Both drugothelin due to inflammation. On the other hand, blood trypomastigotes have been

approved internationadescribed to produce neuraminidase (Figure 1B). All

y. these Antiparasitic treatment of these cardiomyopathies is accompanied by the administration of antiarrhythmics and pace-maker placement. In the most severe cases, heart transplantation can be requiredmechanisms increase platelet adhesiveness and thrombus formation, leading to myocardial ischemia and microinfarcts, which in turn cause tissue necrosis [

541,

742].

24. PathogenicAutoimmune Mechanisms of Immune Response Evasion in in Chagas Disease

MostSeveral of the mechanisms involved in evading the immune response occur in the acute phase, when trypomastigotes establish contact with itheories have been advanced on the development of lesions in heart disease. Among them, the presence of autoimmune

cells of the vertebrate host. Tphenomena and the persistence of the parasite

has evolved mechanisms to survive prstand out, without being mutually exclusive [47]. To

c date

sses such as phagocytosis and the complement system, in addition to interfering with lymphocyte maturation. When metacyclic trypomastigotes contact host cells, either through skin lesions or mucous membranes, there is no consensus regarding the autoimmune hypothesis in the pathogenesis of Chagas disease; however, several studies have demonstrated the participation of mechanisms that could contribute to tissue damage in the chronic phase [47,

48]. Aut

he oimmune

response is activated.damage processes can T. cruzi eorigin

ate

rs cells through

two mainseveral mechanisms

. The first one is lysosome-dependent, which favors C: (1) In the acute phase, lysis of infected vertebrate cells leads to a

2+n exposure mo

bilization [18].f cryptic antigens or In with

is stage, molecular mimicry between the parasite

surface glycoprotein gp82 is crucial for cell adhesion and lysosomal fusion at the site of entry. Cruzipain has also been proven to be critical for calcium induction and lysosomand host cell epitopes. (2) The release and presentation of self-antigens. The ensuing production of inflammatory cytokines may exceed the activation threshold, breaking self-tolerance and stimulating T and B lymphocytes [49]. (3) T ce

ll recruitment. It is a cysteine-protease secreted by trypomastigotesactivation without cytokine signaling (bystander activation). (4) Autoantibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity [

19,2050].

TheAll secondfour mechanism

involves invagination of the plasma ms may result in autoimmune damage.

Othe

mbr

ane followed by lysosomal fusion. The acidification process of lysosomes containing the parasite is key to its differentiation into an amastigote processes inherent to the presentation of host antigens after myocardial lysis suggest the existence of cryptic antigens. This is the case in traumatic ophthalmopathies, which

is the replicative form. A disruption of cytoskeletal actin facilitates the mobilization of lysosomes towards the cell periphery, where they will fuseexpose previously cryptic antigens. Since tolerance for these antigens has not been developed, autoreactive clones are produced. Similarly, some cryptic epitopes can show molecular mimicry with

thT. cruzi e

cypitop

lasmic membrane and contribute to the formes, which favors the generation of

a parasitic vacuolethese clones [

2164].

Such After several divisions in the parasitophorous vacuole, where sialic acid residues ara process has been reported in Chagas disease after host cell lysis (Figure 1C).

5. Inflammatory and Cytotoxic Process in the Immunopathogenesis of Chagas Disease

The

infla

dded on the T. cruzi m

em

brane by parasitic trans-sialidases, the phagolysosome is lysed. Thus, trypomastigotes are released into the cytoplasm and bloodstream to infect distant or adjacent tissues and cells [22].

T. cruzi catory process in Chagas disease starts in the acute phase, with the production of proinflammatory cytokines to recruit and induce the activa

tion

also be phagocytosed atof monocytes to the site of infection

by tissue macrophages.. This process Leishmaniais simp

p. alsoortant to control parasit

izes macrophages and develops mechanisms similar to those ofe replication through a T. cruziTh1-type [23]. Somre

Leishmania sp

onse

cies that parasitize cutaneous and peripheral blood macrophages and have been isolated in Latin America are, characterized by the production of interleukins (IL) such as L. mexicanaIL-1,

L. amazonensis, L. venezuelensis, and L. braziliensis; in

t

he Mediterranean, we find L. infantumer-feron gamma (IFN-γ), and

in Asia the

re are L. tropica tumor necrosis factor a

nd L. major [23]. It shoul

d be empha

sized that these species, phylogenetically related to T. cruzi as K (TNF-α). The functions of IFN-γ predominate in

e t

oplastida, can inhibit the antiparasitic function of his mechanism by inducing the production of nitric oxide (NO) in macrophages

, and both genera use this strategy; and initiating the control of blood parasitemia in th

e cis phase of

Leishmania spp., the

y create adisease [74]. safeOn intracellular compartment and continue their life cycle in the mammal, and in the case of T. cruzithe other hand, it has also been reported that IL-10 and IL-4, stimulated by antigens such as cruzipain,

thre

y evadduce the p

hagolysosome and escape to the cytosol for replicationroduction of IFN-γ and NO in macrophages, inhibiting phagocytosis [

24,2575].

As Tno

survive in this extremely oxidative environment inside the macrophages, theted, while the Th1 response protects the host in the acute phase, its T.cruzi de

xpre

ss antioxidant enzymes such as peroxidases, which protect it from reactive oxygen and nitrogen spgulation in the chronic phase leads to cardiac tissue damage by exacerbated, chronic inflammation (Figure 1D) [76]. Molec

iules

within macrophages [26,27].that contribute to In t

his regard, an overexpression of TcCPX in T. cruzi has been shissue damage (DAMPS), specifically of cyto

wn to

correlate with increased parasitemia andxic origin, are generated by inflammat

ory infiltratesion [77]. iIn th

e myocardium [28].

Notablyis regard,

fact

ors such as strain, the level of antioxidant enzyme expression, and the kinetics of association with the phagolysosome may in turnhere is evidence that oxidative stress also induces myocardial lesions in these patients, contribut

e to parasite evasion and persistence in the host. In contrast toing to lesion progression in Chagas disease [78].

As othe

r protozoa, which inhibit phagolysosome maturation, T. cruzi ev condition progresses towa

rd

e macrophage activity by thes chronicity, further mechanisms

mentioned above, and escape from the phagolysosome into the host cell cytoplasm, where they replicate [29]of cytotoxic damage affect cardiac tissue. Initially, oxidative stress is triggered, and reactive oxygen species are released.

OncThe

outside the macrophages or in any ise reactive oxygen species, mainly H2O2 an

fected

tissueOH,

T. cruzi can be

pr

ecognizo-duced by

their different PAMPs, which are mainly glycoinositolphospholipids (GIPLs) and lipopepti-doglycans (LPPG)cytotoxic immune responses that cause lysis in the tissues surrounding the infec-tion [79,80].

TAnothe

se molecules have proter mechanism triggered by the production of reactive

functions because they allow the parasite to survive in hydrolytic environments and promote adherence to mammalian cells for invasion. The complement oxygen species is the increase in NO levels, which stimulates the production of proinflammatory cytokines and the activation of adhesion molecules for rolling, as well as an increased endothelial permeability [81].

6. Fibrotic Mechanisms in Chagas Disease

Cardiac tis

ys

tem features a specialized pathway for mannose recognition in pathogenic organismsue fibrosis is accompanied by cellular inflammatory infiltrates characterized by the presence of macrophages, neutrophils, and

it is known that blood trypomastigotes activate this system; however, the parasite expresses a set of specific surface proteins for complement evasion [30,31]. T. cruzi treosinophils during the acute phase, and by lymphocytic infiltrates in the chronic phase. Acute or chronic fibrosis has been described in humans

-s by i

alidases are crucial for host cell infection by transferring sialic acid from mammalianmmunohistochemistry in postmortem studies, pointing to the relevance of these proinflammatory cells

to their own glycocalyxand fibrotic accompaniment [

3291,92].

TheCardi

r presence is also knomyocytes have also been shown to

reduce the recognition of anti-α-Gal antibodiesactively participate in the

bloodstream, in addition to evading the lytic effect of complement by promoting the conversion of C3 to inactive C3b (iC3b) [33].

T. cruzi inflammatory response by producing chemokines, cytokines, and NO. These factors can trigger leukocytes at-traction, and they have even been suggested to promote fibrosis by sec

alreti

culin (TcCRT) is also involved in the evasion of the lectin pang fibro-blast-activating growth factors and cytokines [93]. It

h

way by binding to MBL or inhibiting the classical complement pathway by binding to C1q. These links inactivate the membrane attack complex (MAC) formation pathwayas been experimentally proven in primary cultures that soluble mediators synthesized by cardiomyocytes can regulate fibronectin synthesis [

3494].

Various Anwo

ther mechanism by whichrks have studied in vitro the p

arasite controls the complement pathway is mediated by the CRP protein, which is anchored to the parasite membrane. This 160-kDa glycoprotein binds non-covalently to C3b and C4b to inhibit the assembly of C3 convertase, rendering it inactive to catalyze the cleavage of the complement system on the parasite surface. Another parasitic protein called T-DAF accelerates the decay of C3 and C5 convertase in the classical and arocess of the extracellular matrix remodeling due to the presence of cytokines, mainly TGF-β, given that fibrosis is a characteristic process in Chagas chronicity. Other studies have reported that both TGF-β and IL-10 are major regulators of the Th1 response in the lapse preceding the onset of tissue damage, and decreasing the activation of phagocytic cells. On the other hand, TGF-β, IL-13, and IFN-γ are directly related to the severity of cardiac dysfunction due to degenerative fibrosis, which induces motility disorders and organ growth [94,95].

7. Conclusions

Alt

oge

rnative pathwaysther, the evasion of the

complement system. The mucin-rich surface ofimmune response by T. cruzi can

be recognized by Toll-like receptors, such as TLR-2, expressed on mac-rophages. This interaction induces the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-12 and TNF-α, and it favord the proinflammatory immune response lead to autonomic heart dysfunction and microvascular disorders. They also activate autoimmune processes that result in the fibrosis that characterizes the

activationchronic phase of the i

NOS pathway in these phagocytes. In addition, cruzipain fromnfection. These mechanisms, triggered by the presence of the parasite or T. cruziits ha

s a proteolytic action on the NF-κB protein complex, inhibiting the transcription of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-12 [35]ntigens, are responsible for the processes that underlie the immunopathogenesis of cardiac lesions in Chagas disease.