Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Catherine Yang and Version 1 by Jerome Chenal.

With the rapid urbanization, the emergence of a middle class is exerting its influence on the urban form and structure. A data-driven approach based on principal component analysis (PCA) has been used to define multidimensionally the middle class and its housing typology.

- urban middle class

- housing typology

- multidimensional analysis

1. Introduction

Today, 57% of the world’s population lives in urban areas, a proportion that is expected to grow to almost 70% by 2050. Approximately 200,000 new city dwellers are added to the world’s population daily, which translates into 5 million new urban dwellers per month in the developing world and 500,000 in developed countries, there are nearly 1000 urban agglomerations with populations of 500,000 or more, three-quarters of which are in developing countries [1]. Urbanization rates are much faster in these countries as demonstrated by the growth rate in Africa, which is ten times higher than in Europe [1]. Urban areas have always been the world’s economic dynamos for centuries, attracting skilled workers and productive businesses and benefiting from economies of scale. Urbanization and per capita GDP tend to move in close synch as countries develop. The economic development leads to the emergence of a new middle class with incomes high enough to become significant consumers of goods and services [2].

As the fastest growing in the world, Africa’s urban middle class has tripled over the last 30 years. The potential of this growing urban middle class can lead to economic growth, human capital development, and poverty reduction [3,4][3][4]. Indeed, the large middle class in Africa can play a key role in supporting socio-economic resilience and socio-political stability [5]. It sustains consumption and drives much of the investment in good education, good health services, and decent housing. Societies with a strong and large middle class have lower crime rates; enjoy higher levels of trust and life satisfaction, as well as greater political stability and good governance [6]. According to the African Development Bank [3], the increase in size and purchasing power of Africa’s middle class has significantly helped reduce poverty and lift previously poor households into the middle class. Therefore, fostering the growth of the middle class has become one of the big challenges which must be met at the highest level of public priorities and interests to policymakers to reap its positive dividends and to make up the socio-economic development deficit in Africa. Designing appropriate and targeted urban policies that can help to expand the middle class and meet their real needs depends, first and foremost, on the exact determination of who falls into this social class and also an understanding of its influence on urban development.

Approaches used to define the middle class are very diverse, even kaleidoscopic, within and across disciplines. Many developed countries use income as a key indicator to define middle-class status, because they consider that income tends to be highly correlated with the other trappings of social class, such as economic security, education levels, and consumer preferences [6,7][6][7]. However, in developing countries, if the middle class is characterized by its ability to serve as a pillar of social and political stability, and the engine of economic development, it should not be a concern focused solely on income and the provision of basic needs; but should be a class carrier of, more than others, the values of democracy, equality, modernity, efficiency, and merit [3,5,8][3][5][8]. Therefore, the income or the level of consumption, alone, does not allow to define the parameters of a social class with these desired socio-economic specifications, especially since the median income is very low in African countries and cannot be widely spread [4,9][4][9]. Thus, the definition of the middle class must be based on observing the social strata living in satisfactory housing and depicting good socio-economic conditions.

The multidimensional approach, based on monetary and non-monetary attributes, seems to be an alternative to the income-based approach widely used in American and European countries. It has the advantage of taking into account the plurality of social class identification, and of giving priority to variables that can exactly differentiate the middle class. Once the middle class is defined and localized in multidimensional terms, it, therefore, becomes easier to design targeted housing policies and to study and track its impact on the housing market and its spatiotemporal evolution.

2. Middle Class Influence Economic Development and Urban Configuration

The dynamics of the middle class play a very important role as a catalyst for economic growth and human capital development. Their lifestyle is typically associated with certain goods, services, and modes of consumption in terms of housing, education, tourism, sport, and health services [7,18][7][10]. With this style, they improve not only their quality of life but also raise income levels for everyone in other social classes.

In terms of economic growth, Norman Loayza et al. (2012) proved that when the size of the middle class increases, social policy on health and education becomes more active, and the quality of governance regarding democratic participation and official corruption improves [19][11]. This does not occur at the expense of economic freedom, as an expansion of the middle class also implies more market-oriented economic policy on trade and finance [7,20][7][12].

Van Stel et al. 2005 show that the middle class also contributes to economic growth and capital accumulation as a source of entrepreneurship and innovation. In countries with more middle-income households, entrepreneurship activities tend to have a positive impact on GDP growth [21][13]. In this sense, a strong middle class is considered an important element to foster small and medium-sized enterprises and to grow a robust entrepreneurial sector [22][14]. Overall, it has been shown, in other studies, that economic growth is stronger in countries where the middle class is strong [23,24][15][16].

In terms of human capital, Duflo and Banerjee (2008) (2019 Nobel prize in Economics) and Brown and Hunter (2004) emphasize that the middle class allocate greater expenses to the education of their children and invest considerably in improving their knowledge and skills [25,26][17][18]. In doing so they participate in the improvement of human capital in the present and future. This will ensure the sustainability of well-being and adequate lifestyle for future generations, and consequently the improvement of current and future GDP per capita [22,23,27][14][15][19].

In terms of housing and urban configuration, many studies show that the rise of the middle class and its new demand for housing represents a tectonic shift in housing quality and urban structure and configuration. The middle-class lifestyle is typically correlated with certain living conditions, such as decent housing, and being secure, affordable, accessible, and close to urban centers [7].

The urban middle class now constitutes an important new market and a major source of revenue for local and global companies. In the future, wpeople are likely to see brands and strategies specifically targeted at this new consumer group [28,29,30][20][21][22].

In China, for example, Choon-Piew (2012) demonstrates how middle-class gated communities have reshaped the urban landscape with the creation of a new territorialization of privilege, lifestyle, and private property [31][23]. Some scholars have further argued that middle-class housing like gated communities is an effective and innovative way of organizing urban structures. This type of housing has become a part of the state’s urban/national developmental agenda in Singapore for example and is less socially and spatially divisive than those depicted elsewhere [17][24].

In Latin America, a range of studies have revealed that the middle income exerts its influence on the housing and the urban configuration. Gated communities with private safety schemes, a pool, and private parking systems are the preferred model for the emerging middle class [13[25][26],32], this has created a new urban configuration that divides the cities into two distinct blocs: settlement for the poor and gated communities for middle and upper class [13,14,16,33][25][27][28][29].

In Africa, many studies, in Sudan and Tanzania for example, state that the expanding middle-income fuels demand for formal and well-located housing, public utilities, infrastructure, and services [34,35,36][30][31][32]. It is worth noting that, due to this new demand, companies that design and promote satellite cities have changed their strategies in order to best accommodate the expanding African middle class. Therefore, urban policies targeting this social class in Africa need first to understand their preferences and their financial capacity of payment services such as decent and well-located housing. The adoption of smart city and smart home concepts can be a good alternative for companies to attract and expand the middle class by offering a good quality of life and enhancing efficiency at a lower cost [37,38][33][34].

3. Middle Class in African Cities

Although the middle class has been extensively studied in academic literature [6,7,9,10,11,20[6][7][9][12][17][31][35][36][37],25,35,39], developing a specific definition of the middle class is still not easy. There is not even a consensus on how to measure the share of the middle-income population [39][37] and it is often compounded by the complexity of the situation.

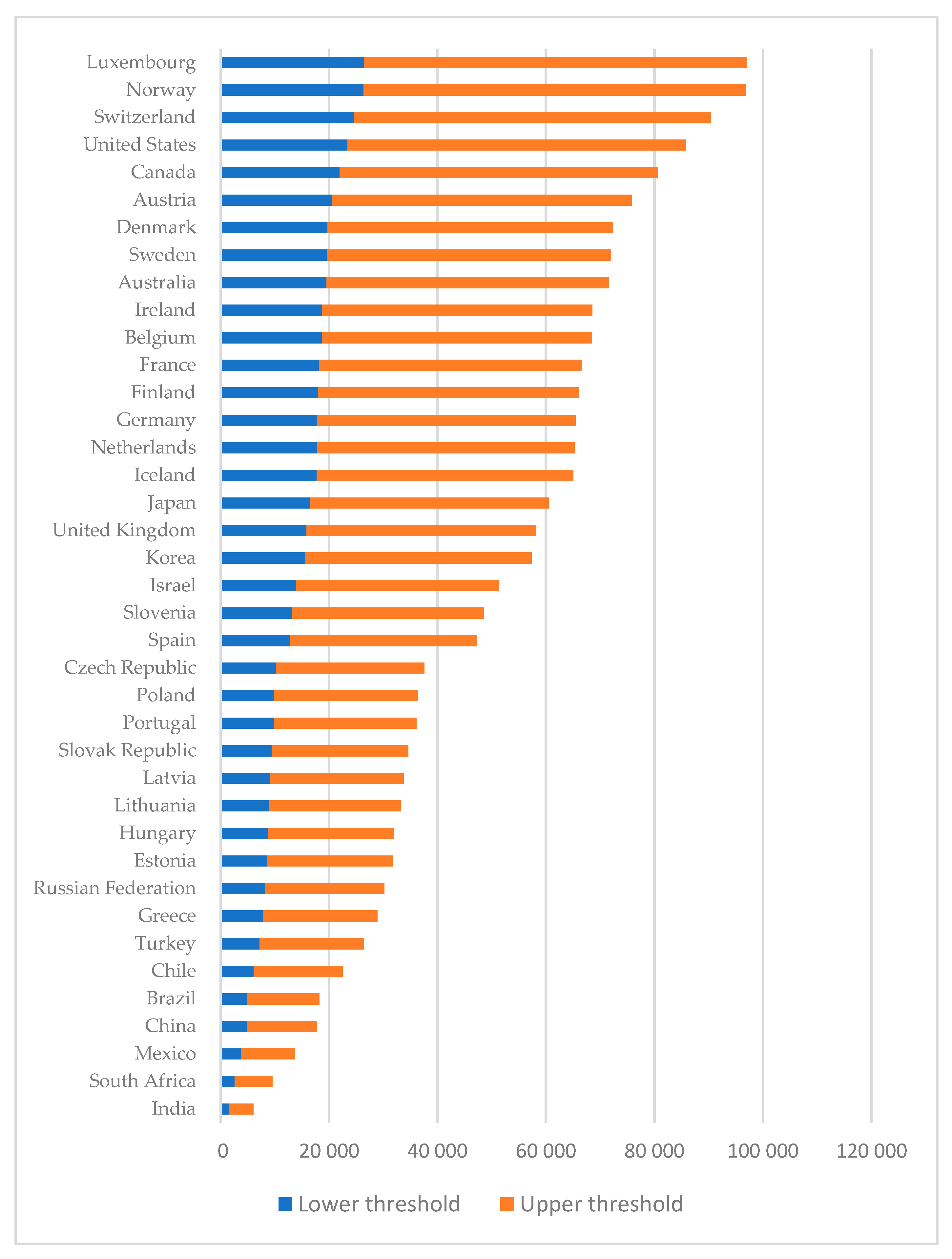

OECD defines the “middle-income class” as the population living in households with incomes ranging between 75% and 200% of the national median. For some of the analyses, the middle-income class is subdivided into three groups: lower-middle incomes (75% to 100% of the median), middle-middle income (100% to 150% of the median), and upper-middle income (150% to 200% of the median). The population in households with income below 75% of the median are the “lower-income class” and those with income above 200% of the median are the “upper-income class”. Based on this definition, the annual income of the middle class in the United States is between USD 23,000 and 62,000, while in Mexico or India is respectively between USD 3757 and 10,019 and USD 1656 and 4417 (Figure 1) [6].

Figure 1. Middle-income thresholds in OECD countries and selected emerging economies. Note: Middle-classes and median incomes are defined relative to equivalised household disposable income. The middle-income class comprises individuals in households with incomes of between 75% and 200% of the median [6].

The World Bank uses the absolute approach based on the income thresholds to determine the middle class in the emerging economies of Latin America and the Caribbean. It sets lower and upper thresholds of USD 10 and 50 per day, adjusted for international differences in purchasing power [40][38]. Indicators based on absolute amounts are intuitive and easily understandable by the public. However, they are more suitable for emerging economies, where analyses of absolute living standards are more widely used.

The African Development Bank and the Asian Development Bank have also chosen an absolute measure, defining the middle class as the class made up of people whose consumption expenditures range between USD 2 and 20 in 2005. The African Development Bank divides the middle class into three sub-groups: (1) the lower-middle class, which ranges from individuals consumption between USD 2 and 4 per day, a rate that exceeds very slightly the poverty line in developing countries, making this the first group vulnerable to external shocks; (2) the middle class with consumption ranging between 4 and 10 dollars per day, a category of the population that lives above the level of essential needs and is, therefore, able to save and consume basic goods; (3) the upper-middle class, whose consumption ranges between USD 10 and 20 per day. In addition, the African Development Bank uses a different definition depending on the level of income of the country concerned: between UDS 2 and 10 for poor countries, and between USD 10 and 20 for middle countries.

Although these approaches are based on simple economic definitions, it does not take into account the socio-economic characteristics usually associated with the middle class in many countries (education, lifestyle, occupation, decent housing). In addition, there is a risk of classifying as middle-class people that belong to the poor class according to the absolute approach specifically in developing countries [5]. Deloitte for example is cautious on the definition of a middle class used by the African Development Bank. It considers that it is difficult to imagine how households with such minimal purchasing capacities can afford decent housing as well as the vehicles needed to move around the city, and it may be that prospective property developers are seriously misreading the African market [4].

In Africa and developing countries in general, many constraints make it difficult to define the middle class, based on the income or consumption level. Recent studies highlight that the lack of regularly updated data on the middle class, the weakness of the statistical framework for tracking salaries in the private sector, the size of the informal sector, and the weakness of statistics related to it, all constitute major difficulties that hinder an effective and precise definition of the middle class in these countries.

References

- UN. Revision of World Urbanization Prospects; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2018.

- Dobbs, R.; Remes, J.; Manyika, J.; Roxburgh, C.; Smit, S.; Schaer, F. Urban World: Cities and the Rise of the Consuming Class; McKinsey Global Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2012.

- Ncube, M.; Leyeka Lufumpa, C.; Kayizzi-Mugerwa, S. The Middle of the Pyramid: Dynamics of the Middle Class in Africa; African Development Bank Group: Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 2011; p. 24.

- Chimhanzi, J.; Gounden, A. The Rise and Rise of the African Middle Class. Deloitte Afr. Collect. 2013, 1, 1–5.

- CESE. Elargissement de la Classe Moyenne, Locomotive du Développement Durable et de la Stabilité Sociale; Conseil Economique Social et Environnemental-Maroc: Rabat, Morocco, 2021.

- OECD. Under Pressure: The Squeezed Middle Class; Edition OCDE; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development: Paris, France, 2019; ISBN 978-92-64-54283-9.

- Reeves, R.V.; Guyot, K.; Monday, E.K. Defining the Middle Class: Cash, Credentials, or Culture? Brookings: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. 24.

- Arbouch, M.; Dadush, U. Measuring the Middle Class in the World and in Morocco; Policy Center: Rabat, Morocco, 2019; p. 24.

- Edo, M.; Escudero, W.S.; Svarc, M. A Multidimensional Approach to Measuring the Middle Class. J. Econ. Inequal. 2021, 19, 139–162.

- Nijman, J. Mumbai’s Mysterious Middle Class. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2006, 30, 758–775.

- Loayza, N.; Rigolini, J.; Llorente, G. Do Middle Classes Bring about Institutional Reforms? Econ. Lett. 2012, 116, 440–444.

- Kharas, H. The Emerging Middle Class in Developing Countries. OECD Dev. Cent. Work. Pap. 2010.

- Van Stel, A.; Carree, M.; Thurik, R. The Effect of Entrepreneurial Activity on National Economic Growth. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 311–321.

- OCDE. Sous Pression: La Classe Moyenne en Perte de Vitesse; OECD: Paris, France, 2019; ISBN 978-92-64-99556-7.

- Brueckner, M.; Dabla-Norris, E.; Gradstein, M.; Lederman, D. The Rise of the Middle Class and Economic Growth in ASEAN. J. Asian Econ. 2018, 56, 48–58.

- Easterly, W. The Middle Class Consensus and Economic Development. J. Econ. Growth 2001, 6, 317–335.

- Banerjee, A.V.; Duflo, E. What Is Middle Class about the Middle Classes around the World? J. Econ. Perspect. 2008, 22, 3–28.

- Brown, D.S.; Hunter, W. Democracy and Human Capital Formation: Education Spending in Latin America, 1980 to 1997. Comp. Polit. Stud. 2004, 37, 842–864.

- OECD. The Sources of Economic Growth in OECD Countries; Edition OCDE; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2003; ISBN 978-92-64-19945-3.

- Cavusgil, S.T.; Deligonul, S.; Kardes, I.; Cavusgil, E. Middle-Class Consumers in Emerging Markets: Conceptualization, Propositions, and Implications for International Marketers. J. Int. Mark. 2018, 26, 94–108.

- Donmaz, A.; Sayil, E.; Havayolları, A.; Bölümü, B. The Growth & Importance of Middle Class Consumers in Emerging Markets; IBANESS Conference Series: Kırklareli, Turkey, 2017.

- Javalgi, R.G.; Grossman, D.A. Aspirations and Entrepreneurial Motivations of Middle-Class Consumers in Emerging Markets: The Case of India. Int. Bus. Rev. 2016, 25, 657–667.

- Choon-Piew, P. Gated Communities in China, Reprint ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-415-53351-5.

- Pow, C.-P. Public Intervention, Private Aspiration: Gated Communities and the Condominisation of Housing Landscapes in Singapore. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2009, 50, 215–227.

- Short, J.R.; Martínez, L. The Urban Effects of the Emerging Middle Class in the Global South. Geogr. Compass 2020, 14, e12484.

- Borsdorf, A. Condominios Fechados and Barrios Privados: The Rise of Private Residential Neighbourhoods in Latin America; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 92–108. ISBN 978-0-415-34170-7.

- Janoschka, M.; Sequera, J. Gentrification in Latin America: Addressing the Politics and Geographies of Displacement. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 1175–1194.

- Steel, G.; van Noorloos, F.; Klaufus, C. The Urban Land Debate in the Global South: New Avenues for Research. Geoforum 2017, 83, 133–141.

- Delgadillo, V. Selective Modernization of Mexico City and Its Historic Center. Gentrification without Displacement? Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 1154–1174.

- Watson, V. African Urban Fantasies: Dreams or Nightmares? Environ. Urban. 2014, 26, 215–231.

- Mercer, C. Boundary Work: Becoming Middle Class in Suburban Dar Es Salaam. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2020, 44, 521–536.

- Azza, A.M.B. Urban Planning and the Reconfiguration of Tuti Island; Nationalmuseet: Khartoum, Sudan, 2020; p. 19.

- Irvine, K.N.; Suwanarit, A.; Likitswat, F.; Srilertchaipanij, H.; Ingegno, M.; Kaewlai, P.; Boonkam, P.; Tontisirin, N.; Sahavacharin, A.; Wongwatcharapaiboon, J.; et al. Smart City Thailand: Visioning and Design to Enhance Sustainability, Resiliency, and Community Wellbeing. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 7.

- Aliero, M.S.; Asif, M.; Ghani, I.; Pasha, M.F.; Jeong, S.R. Systematic Review Analysis on Smart Building: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3009.

- Gayo, M. Revisiting Middle-Class Politics: A Multidimensional Approach–Evidence from Spain. Sociol. Rev. 2013, 61, 814–837.

- Davis, J.C.; Huston, J.H. The Shrinking Middle-Income Class: A Multivariate Analysis. East. Econ. J. 1992, 18, 277–285.

- Pressman, S. Defining and Measuring the Middle Class; American Institute for Economic Research: Great Barrington, MA, USA, 2015; p. 27.

- Ferreira, F.H.G.; Messina, J.; Rigolini, J.; López-Calva, L.-F. Maria Ana Lugo Economic Mobility and the Rise of the Latin American Middle Class|World Bank Latin American and Caribbean Studies. Available online: https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/978-0-8213-9634-6 (accessed on 4 August 2021).

More