Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Andrew John Simkin and Version 3 by Sirius Huang.

Fruits are an important source of vitamins, minerals and nutrients in the human diet. They also contain several compounds of nutraceutical importance that have significant antioxidant and anti-inflammatory roles. Cherries contain high concentrations of bioactive compounds and minerals, including calcium, phosphorous, potassium and magnesium, and it is, therefore, unsurprising that cherry consumption has a positive impact on health. The sweet cherry fruit is a drupe—an indehiscent fruit of 1–2 cm in diameter (in some cultivars the diameter can be larger) that has an attractive appearance due to its color (bright red to dark purple depending on the cultivar) and desirable, intense flavor.

- tree fruit

- fruit ripening

- rootstock

- Prunus avium

1. Introduction

Cherry (Prunus avium) is believed to be native to Europe and southern Asia [1] and to a small isolated region in the western Himalayas. Commonly called sweet cherry, it is a deciduous tree, 15–32 m in height and with a trunk up to 1.5 m in circumference. It belongs to the Rosaceae family, which includes many plants, such as rose, apple (Malus x domestica), peach (Prunus persica) and strawberry (Fragaria vesca and F. ananassa) that are very important for the human economy. The sweet cherry genome is diploid (2n = 16), simple, compact and about 350 Mb in size. The genome structure is predicted to be similar to that of the peach, although the sequences have diverged [2][3][4][2,3,4] See (http://www.rosaceae.org accessed on 1 June 2022) [5].

Young cherry trees show strong apical dominance with a straight trunk and symmetrical conical crown that becomes rounded to irregular for old trees. All parts of the plant, except for the ripe fruit, are slightly toxic, due to the presence of cyanogenic glycosides. The species has also become naturalized in North America and Australia since it is largely cultivated in these regions.

2. Cherry from Flower to Fruit

2.1. Cherry Flower Pollination

The sweet cherry flower is hermaphroditic; possessing both female and male reproductive organs. Each flower is approximately 2.5 cm in diameter, with five petals surrounded by five green sepals, a single upright pistil with an ovary, two ovules, and 30 stamens. The stamens are the male reproductive organs consisting of anthers, where the pollen develops; it sits on top of the stalk-like filaments, which allows water and nutrients to reach the anthers from the mother plant and facilitate pollen dispersal [6][7][6,7]. The pistil or gynoecium is the female reproductive organ, and it occupies the centre of the flower. The flowers open for between three and five days and the stigma is receptive to pollination at this time. The anthers begin to open shortly after the flower and continue into the second day [8]. In sweet cherry, it takes two to three days for the pollen tube to grow from the stigma to the base of the style, whilst fertilization occurs six to eight days after pollination [9][10][9,10]. Stösser and Anvari [11] determined that effective pollination takes between 4 and 5 days; however, under some conditions, effective pollination can last up to 13 days [12]. There are a number of varieties of sweet cherry that exhibit self-fertility, the first and most notable being ‘Stella’, which was first identified in Canada [13], and is highly sought-after and considered a cultivar of great importance [14][15][16][14,15,16]. However, most sweet cherry cultivars exhibit self-incompatibility (SI), a characteristic that involves inhibition of pollen tube growth, and is genetically controlled by multiple allelic S-loci [17][18][19][20][17,18,19,20]. SI sweet cherry varieties still produce a small number of fruit through self-pollination; however, different varieties are considered to have different levels of self-sterility, with important commercial varieties, such as ‘Kordia’ and ‘Regina’ being highly incompatible and setting virtually no fruit in the absence of cross-pollination [21]. The nectar of sweet cherry is rich in sugars (from 28% to 55% sugar), the most abundant of which are fructose, glucose and sucrose, which are highly attractive to pollinating insects, including bees [22]. It is well known that insect-mediated pollination in sweet cherry is important for the production of a viable crop and besides the environmental conditions, pollinating insects are the most important factor governing yield [23]. Work by Holzschuch et al. [24] showed that bagged flowers produced only 3% of the number of fruits produced by unbagged flowers and that the rates of pollination and fruit set were related to wild bee visitation. Wild pollinators, including solitary bees, have been described as being instrumental in achieving adequate sweet cherry yields [25]. These authors also showed that pollination by wild bees surpassed pollination by honeybees. However, even with this knowledge, less than 17% of growers provide trap nests for solitary bees in their orchards and rely on commercial domesticated honeybees (Apis mellifera) to carry out this function at a cost up to 1000 Euro per hectare—a considerable investment for commercial cherry producers. A recent review has outlined grower knowledge of the role of insects on sweet cherry crops [23]. Air temperature is also known to influence flowering and fruit sets and has no influence on the level of SI; however, the air temperature may influence pollen tube growth [26]. The optimal temperature for flowering has been reported to be around 20 °C, with temperatures as low as 15 °C slowing the disappearance of the embryo sac, as compared to 25 °C [27]. Temperatures exceeding 30 °C are considered too high for successful flowering [26][28][29][26,28,29]. Furthermore, it has been reported that a sudden fall in temperature at the end of the flowering period can result in a total loss of the crop [21].2.2. The ABCDE and the Floral Quartet Models

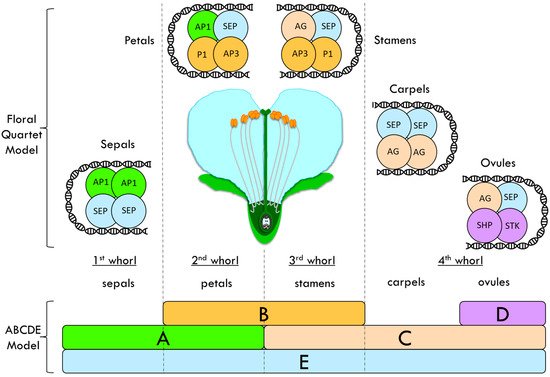

Flower organs are arranged in whorls, with sepals that are located in the most external whorl and carpels in the inner whorl, in the form of petals and stamens. Floral homeotic mutants, i.e., mutants with an altered floral organ identity, such as in Arabidopsis thaliana and Antirrhinum majus (snapdragon), have been studied and used to propose the ABC model of flower formation [30][31][30,31]. ABC genes encode three different classes of MADS-domain transcription factors involved in the flower organ identity determination. These factors interact to give the organ identity to sepal, petals, stamens and carpel. Further studies showed the existence of two other classes: the D class, which is responsible for the ovule identity, and the E-class, which has been proposed as another class of redundant floral organ identity genes [32]. This enhanced ABCDE model postulates that sepals are specified by A + E, petals by A + B + E, stamens by B + C + E, carpels by C + E and ovules by C + D + E (Figure 12) [32][33][34][35][32,33,34,35].

Figure 12. Floral quartet model (FQM) integrated into the ABCDE model proposed to explain the flower whorls’ identity determination in Arabidopsis thaliana. This enhanced ABCDE model postulates that sepals are specified by A + E, petals by A + B + E, stamens by B + C + E, carpels by C + E and ovules by C + D + E. Class-A protein: APETALA1 (AP1); Class-B proteins: PISTILLATA (PI) and APETALA3 (AP3); Class-C protein: AGAMOUS (AG); Class-D proteins: SEEDSTICK (STK) and SHATTERPROOF (SHP); Class-E protein: SEPALLATA (SEP).

- MADS (M) domain: a DNA-binding domain, but it is also involved in dimerization and in nuclear localization. It is the most conserved domain among the MADS-box transcription factors [36].

- ].

-

MADS (M) domain: a DNA-binding domain, but it is also involved in dimerization and in nuclear localization. It is the most conserved domain among the MADS-box transcription factors [36].

- Intervening (I) domain: takes part in the selective formation of DNA-binding dimers. It shows only limited conservation

- [37].

- Keratin-like (K) domain: an essential element for dimerization and multimeric complex formation. This domain has a particular structural organization (amphipathic helices) in which the hydrophobic and charged residues are conserved and regularly spaced [38

-

Intervening (I) domain: takes part in the selective formation of DNA-binding dimers. It shows only limited conservation [37].

- ]

- ].

- [

- 39

- ].

- Keratin-like (K) domain: an essential element for dimerization and multimeric complex formation. This domain has a particular structural organization (amphipathic helices) in which the hydrophobic and charged residues are conserved and regularly spaced [38,

-

C-terminal (C) domain: is somewhat variable. In some cases, it takes part in the transcriptional activation of the target genes or in the formation of multimeric complexes [37].

3. Cherry Fruit Development

3.1. Cherry Fruit

The sweet cherry fruit is a drupe—an indehiscent fruit of 1–2 cm in diameter (in some cultivars the diameter can be larger) that has an attractive appearance due to its color (bright red to dark purple depending on the cultivar) and desirable, intense flavor. Three parts can be identified in a drupe: the outer exocarp or skin; the mesocarp, which is the fleshy part of the fruit; and a single central stone, which is the lignified endocarp that surrounds the seed. Drupe development in cherry fruit is consistent with the reported stages of growth in other drupes, as described below. Cherry varieties can be divided into early, mid and late ripening types (Table 1) based on the ripening of the reference variety at the European level, Burlat, a widespread cultivated cherry across Europe.Table 1. Some of the most commonly commercially cultivated varieties of sweet cherry. Early, mid and late ripening types based on the ripening of the reference variety, Burlat, a widespread cultivated cherry across Europe. Comparisons to the variety Bing are based on interviews with growers in Stanislaus County, California and on published data. NR—not reported.

| Ripen | Days Post-Burlat * | Days Post Bing ** | Variety | Reported Qualities and Region of Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burlat | 0 | NR | Burlat | The most widespread and cultivated cherry among existing varieties. It has good flavor, high resistance to cracking compared to most varieties, and exceeds in its time. |

| Early | 0–11 | NR | Merchant | Self-sterile, mature 7 days post-Burlat. Producing good yields of large, dark red fruit in early summer. Self-sterile, mature 9 days after Burlat. |

| NR | Carmen | Developed and cultivated in Hungary. Fruit have large size and good flavor. Spreading in Germany due to its high yields. | ||

| Mid | 12–19 | NR | Grace Star | Recent Italian variety. Self-fertile with maturation occurring 12 days post-Burlat. Large fruit, firm texture, excellent flavor qualities, and highly valued by consumers. |

| −5 | CristalinaTm | Self-sterile cherry of Canadian origin. Mature 12 days post-Burlat. High productivity, under conditions of moderate load. Fruit have good firmness and very good flavor and is moderately sensitive to cracking. | ||

| 0 | Stella | One of the first self-fertile varieties (Canadian origin). Ripens 19 days post-Burlat. Large fruit, blood-red hue, good resistance to cracking, sensitive to cold. Highly sought-after. Considered a cultivar of great importance. | ||

| Bing | Bing | Most traditional and representative cherry of America. Ripening occurs 19 days post-Burlat. Fruit are dark red, large, firm, and highly valued for their excellent flavor and is the preeminent fresh-market cherry. | ||

| 0 | Rainer | Bicolor cherry from the United States. The variety is self-sterile and ripens 19 days post-Burlat. Variety is appreciated by the industry owing to the large size and good flavor of the fruit. | ||

| Late | 20–27 | NR | Kordia | Originating in the Czech Republic with good resistance to cracking. Very popular in Germany. Ripens 24 days post-Burlat. Known for large, firm fruit and good flavor. Highly incompatible and setting virtually no fruit in the absence of cross-pollination. |

| 3 | SonataTm | Self-fertile Canadian variety with good productivity. Ripens 22 days post-Burlat. Fruit have a good taste and are large and firm in size. Unfortunately, it is highly susceptible to cracking. | ||

| 5–7 | Lapins | Highly productive self-fertile from the United States. Currently, most planted cherry in the world. Good flavor with cracking resistance. Variety is appreciated by farmers. Ripens 24 days post-Burlat (see SkeenaTm). | ||

| 7–10 | BentonTm | Another self-fertile cherry tree that ripens mid-season and has been reputed to surpass Bing cherries. | ||

| 10–14 | SkeenaTm | Characterized as an improved Lapins. Similar characteristics, but lower productivity, which helps to produce cherries of greater caliber and quality. In the United States, replacing Lapins. Mature 25 days post-Burlat. | ||

| 11–13 | SweetheartTm | Late maturation with large fruit. Prolific fruiters with a dark red, medium to large cherries. Pruning is required to keep trees productive. | ||

| Extra Late | More than 28 | NR | Regina | Self-sterile variety of German origin. Low productivity with maturation occurring 31 days post-Burlat. Large sized fruit, good taste and cultivated due to its high resistance to cracking. Highly incompatible and setting virtually no fruit in the absence of cross-pollination. |

| NR | Ambrunes | Spanish Cherry is traditionally grown in Cáceres. Firm fruit with very good flavor. High resistance to cracking. Ripens 31 days post-Burlat. |

- C-terminal (C) domain: is somewhat variable. In some cases, it takes part in the transcriptional activation of the target genes or in the formation of multimeric complexes

- [

- 37

* https://en.excelentesprecios.com/cherry-tree-varieties, (3 June 2022); ** https://m.blog.naver.com/PostView.naver?isHttpsRedirect=true&blogId=2jw67&logNo=90164242596 1 June 2022. Tm = trademark.

During early fruit development, there is constant communication between the developing fruit and the developing seed. These signals can be hormones, such as auxin and gibberellins, produced in the endosperm or in the seed coat and are involved in the developmental synchronization of all these different structures [41][42][43][44][41,42,43,44]. The disruption of this communication is one of the triggers of fruit drop—the loss of a significant proportion of their fruit before ripening. This loss, which is often referred to as ‘June Drop’ or ‘Cherry Run Off’, varies from year to year and, in some seasons, can result in a total loss of the crop.

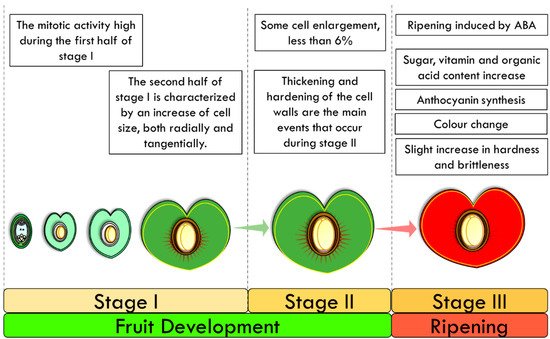

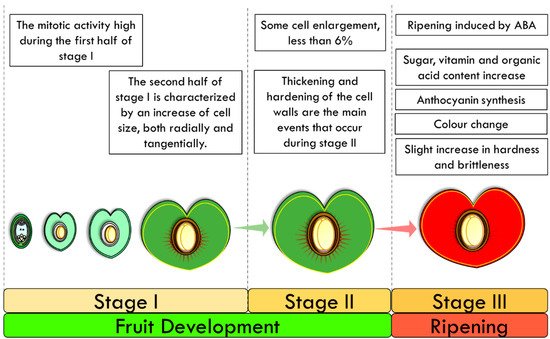

The outer epidermis of the developing cherry fruit consists of a single row of cells that are covered externally by a cuticle, which is interrupted only where the stomata are present (see Section 4). During the pre-flowering period, the cells of the epidermis are already well-differentiated, with an elongated shape and no hairs, and increase their size slowly, mainly in the radial direction. The mitotic activity is low since the increase in the number of cells is very limited, while it is high during the first half of stage I (Figure 34). The second half of stage I is characterized by an increase in cell size, both radially and tangentially. Moreover, during the second half of stage I, the cuticle reaches its full thickness. No cell division is observed during stage II, which is characterized by slight tangential elongation of cells and additional cell wall thickening. Lastly, during the final phase (stage III), cells start to enlarge by as much as 100-fold, contributing to the final fruit size. After these three phases, a green immature fruit is formed, which has the dimensions of the mature fruit and starts the maturation process [45][46][47][48][49][50][51](see Section 3.3) [45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. A more than two-fold tangential enlargement of the cells occurs, with a decrease in the radial diameter and cuticle thickness, in order to generate a large increase in the fruit surface area [53].

The outer epidermis of the developing cherry fruit consists of a single row of cells that are covered externally by a cuticle, which is interrupted only where the stomata are present (see Section 4). During the pre-flowering period, the cells of the epidermis are already well-differentiated, with an elongated shape and no hairs, and increase their size slowly, mainly in the radial direction. The mitotic activity is low since the increase in the number of cells is very limited, while it is high during the first half of stage I (Figure 34). The second half of stage I is characterized by an increase in cell size, both radially and tangentially. Moreover, during the second half of stage I, the cuticle reaches its full thickness. No cell division is observed during stage II, which is characterized by slight tangential elongation of cells and additional cell wall thickening. Lastly, during the final phase (stage III), cells start to enlarge by as much as 100-fold, contributing to the final fruit size. After these three phases, a green immature fruit is formed, which has the dimensions of the mature fruit and starts the maturation process [45][46][47][48][49][50][51](see Section 3.3) [45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. A more than two-fold tangential enlargement of the cells occurs, with a decrease in the radial diameter and cuticle thickness, in order to generate a large increase in the fruit surface area [53].

During the pre-bloom period, the fleshy mesocarp is composed of isodiametric parenchymatous cells, which elongate according to a gradient tangentially to slightly radial from the epidermis to the stony endocarp, respectively. The increase in tissue thickness, more than double, is due mostly to cell division. The first half of stage I is characterized by cell mitotic divisions, accomplishing an increase of about 20–30% in the number of cells from the epidermis to the stone, and no further divisions are observed after completion of this stage [53]. The cells increase in diameter more than four-fold, mostly during the second half of stage I. Moreover, differentiation of a hypodermal layer, five or six cells thick, occurs just under the epidermis, by considerable thickening of the cells. These cells become slightly greater in size than those of the epidermis and become tangentially elongated. On the other side, adjacent to the stone, a layer of small isodiametric cells, three or four cells wide, differentiates, during the second half of stage I. During stage II, some cell enlargement, less than 6%, occurs and intercellular spaces remain prominent. The cells just under the epidermis continue slowly to elongate tangentially, while limited cell division can be found in the thin layer of small cells adjacent to the stone, otherwise, there is none. Stage III is also called “the final swell” and during this period, four parts of the fleshy mesocarp can be recognized (from the epidermis to the stony endocarp):

During the pre-bloom period, the fleshy mesocarp is composed of isodiametric parenchymatous cells, which elongate according to a gradient tangentially to slightly radial from the epidermis to the stony endocarp, respectively. The increase in tissue thickness, more than double, is due mostly to cell division. The first half of stage I is characterized by cell mitotic divisions, accomplishing an increase of about 20–30% in the number of cells from the epidermis to the stone, and no further divisions are observed after completion of this stage [53]. The cells increase in diameter more than four-fold, mostly during the second half of stage I. Moreover, differentiation of a hypodermal layer, five or six cells thick, occurs just under the epidermis, by considerable thickening of the cells. These cells become slightly greater in size than those of the epidermis and become tangentially elongated. On the other side, adjacent to the stone, a layer of small isodiametric cells, three or four cells wide, differentiates, during the second half of stage I. During stage II, some cell enlargement, less than 6%, occurs and intercellular spaces remain prominent. The cells just under the epidermis continue slowly to elongate tangentially, while limited cell division can be found in the thin layer of small cells adjacent to the stone, otherwise, there is none. Stage III is also called “the final swell” and during this period, four parts of the fleshy mesocarp can be recognized (from the epidermis to the stony endocarp):

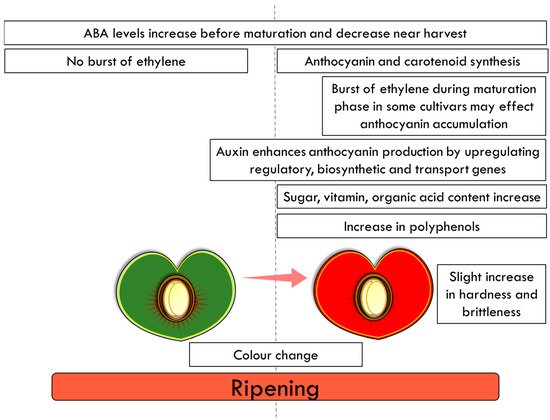

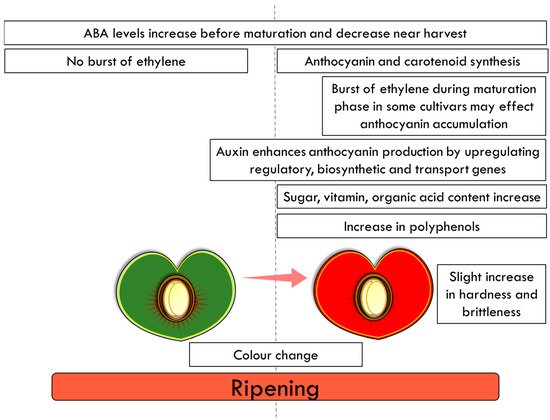

Cherry ripening is associated with changes in colour, sugar, vitamin and organic acid content (Figure 45). In sweet cherries, ABA has been associated with the regulation of anthocyanin synthesis and the organoleptic properties (ratio of total soluble sugars to total acidity) [64][66][73][64,66,73]. The colour of the fruit is attributed to the accumulation of these water-soluble health-promoting anthocyanins (a class of flavonoids), which are responsible for the blue, purple and red colours [74][75][74,75]. In addition to ABA, cytokinins, jasmonic acid (JA), gibberellins (GAs), and auxins, all play roles in the ripening of non-climacteric fruit. Auxin (1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA)) treatment has been shown to enhance anthocyanin production in sweet cherry by upregulating key anthocyanin regulatory, biosynthetic and transport genes [76]. This study demonstrated that treatment with NAA alters ethylene production, induces ripening, and enhances anthocyanin production, probably through ABA metabolism [76].

Size, colour, firmness, sweetness and flavour intensity are considered the most critical attributes that drive consumer acceptance and, ultimately, the value of the crop to the producers [77][78][79][80][77,78,79,80]. However, consumers from different countries and regions place different values on their requirements for a good cherry. For example, consumers in Norway prefer dark, large cherries [81][82][81,82]. Similar results were found in the UK [83] and in American markets [84]. These consumer requirements may differ from those of the growers and supermarkets. Growers want cherries that are resistant to cracking and can be left on the trees longer to ripen, are easy to harvest (long peduncles) and firm enough to resist damage during picking, processing, and transporting. Supermarkets want cherries with long shelf lives, even weeks once in store.

Cherry ripening is associated with changes in colour, sugar, vitamin and organic acid content (Figure 45). In sweet cherries, ABA has been associated with the regulation of anthocyanin synthesis and the organoleptic properties (ratio of total soluble sugars to total acidity) [64][66][73][64,66,73]. The colour of the fruit is attributed to the accumulation of these water-soluble health-promoting anthocyanins (a class of flavonoids), which are responsible for the blue, purple and red colours [74][75][74,75]. In addition to ABA, cytokinins, jasmonic acid (JA), gibberellins (GAs), and auxins, all play roles in the ripening of non-climacteric fruit. Auxin (1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA)) treatment has been shown to enhance anthocyanin production in sweet cherry by upregulating key anthocyanin regulatory, biosynthetic and transport genes [76]. This study demonstrated that treatment with NAA alters ethylene production, induces ripening, and enhances anthocyanin production, probably through ABA metabolism [76].

Size, colour, firmness, sweetness and flavour intensity are considered the most critical attributes that drive consumer acceptance and, ultimately, the value of the crop to the producers [77][78][79][80][77,78,79,80]. However, consumers from different countries and regions place different values on their requirements for a good cherry. For example, consumers in Norway prefer dark, large cherries [81][82][81,82]. Similar results were found in the UK [83] and in American markets [84]. These consumer requirements may differ from those of the growers and supermarkets. Growers want cherries that are resistant to cracking and can be left on the trees longer to ripen, are easy to harvest (long peduncles) and firm enough to resist damage during picking, processing, and transporting. Supermarkets want cherries with long shelf lives, even weeks once in store.

3.2. Physiological Changes during Cherry Fruit Development

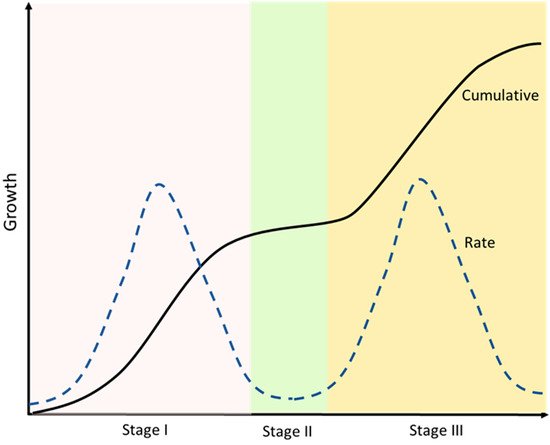

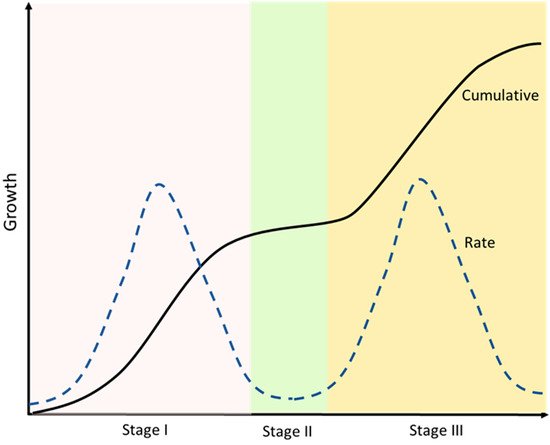

The developmental growth rate of the drupe can be described by a double sigmoid curve, where three well-marked stages can be identified (Figure 23). In the first phase (stage I), the ovary either aborts or starts all the subsequent morphological changes that will lead to the formation of the fruit [45][46][47][48][49][50][51][45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. The traditional definition of phase I, beginning at anthesis, also includes the acceleration of the growth of the ovary approximately two weeks before anthesis [52].

Figure 23. A double sigmoid growth curve representation. Cumulative and rate of growth are defined. After an initial exponential phase (Stage I) a second plateau phase occurs (Stage II), which is followed then by a second exponential phase (Stage III) until the complete ripening of the fruit. Developmental phases are allocated with respect to peaks and troughs in growth rate.

Figure 34. Fruit Ripening in the cultivated cherry. After an initial exponential phase (Stage I) a plateau phase occurs (Stage II), which is followed then by a second exponential phase (Stage III) until the complete ripening of the fruit.

- The hypodermal layer of collenchyma;

- The peripheral layer of thin-walled parenchyma, extending to a line just inside the ring of vascular bundles;

- The layer of radially elongated cells, extending from this line nearly to the stone;

- The thin layer of small cells adjacent to the stone.

3.3. Final Ripening Stages of Mature Cherry

Fruit ripening is a highly variable process with numerous differences when different plant species are compared; however ripening is often characterized by the accumulation of pigments, such as carotenoid sand anthocyanins (Figure 45) [56]. Despite these differences, fruit ripening has been classified into two distinct groups, climacteric and non-climacteric, which differ in their patterns of ethylene production and respiration at the onset of the ripening process [57][58][57,58]. Climacteric fruit, such as tomato, display a rise in respiration and a burst of ethylene modulating the differentiation of chloroplast to chromoplast and the accumulation of carotenoids [59][60][59,60]. In contrast, cherry fruit are non-climacteric and ripening is promoted by abscisic acid (ABA) [61]. No burst of ethylene and respiration has been observed in sweet cherry during fruit development and ripening. Moreover, the exogenous ethylene treatment has no significant effects on the fruit’s respiration rate or on its softening [62][63][62,63]. Ethylene concentrations remain low [64][65][64,65], although ethylene may affect the accumulation of anthocyanins [66]. However, it should be noted that the ethylene concentration in some sweet cherry cultivars has been shown to increase sharply before harvest [67], suggesting that it may play some role in fruit ripening during the maturation phase of development [68]. In sweet cherry, ABA levels increase before maturation and decrease near harvest [64][69][64,69]. Furthermore, in grapes, another non-climacteric fruit, the onset of ripening is ABA related; ABA modulates the changes in colour and the accumulation of sugars and has a role in fruit softening in the later stages of ripening [70][71][72][70,71,72].

Figure 45.

Final stages of fruit ripening in the cultivated cherry.