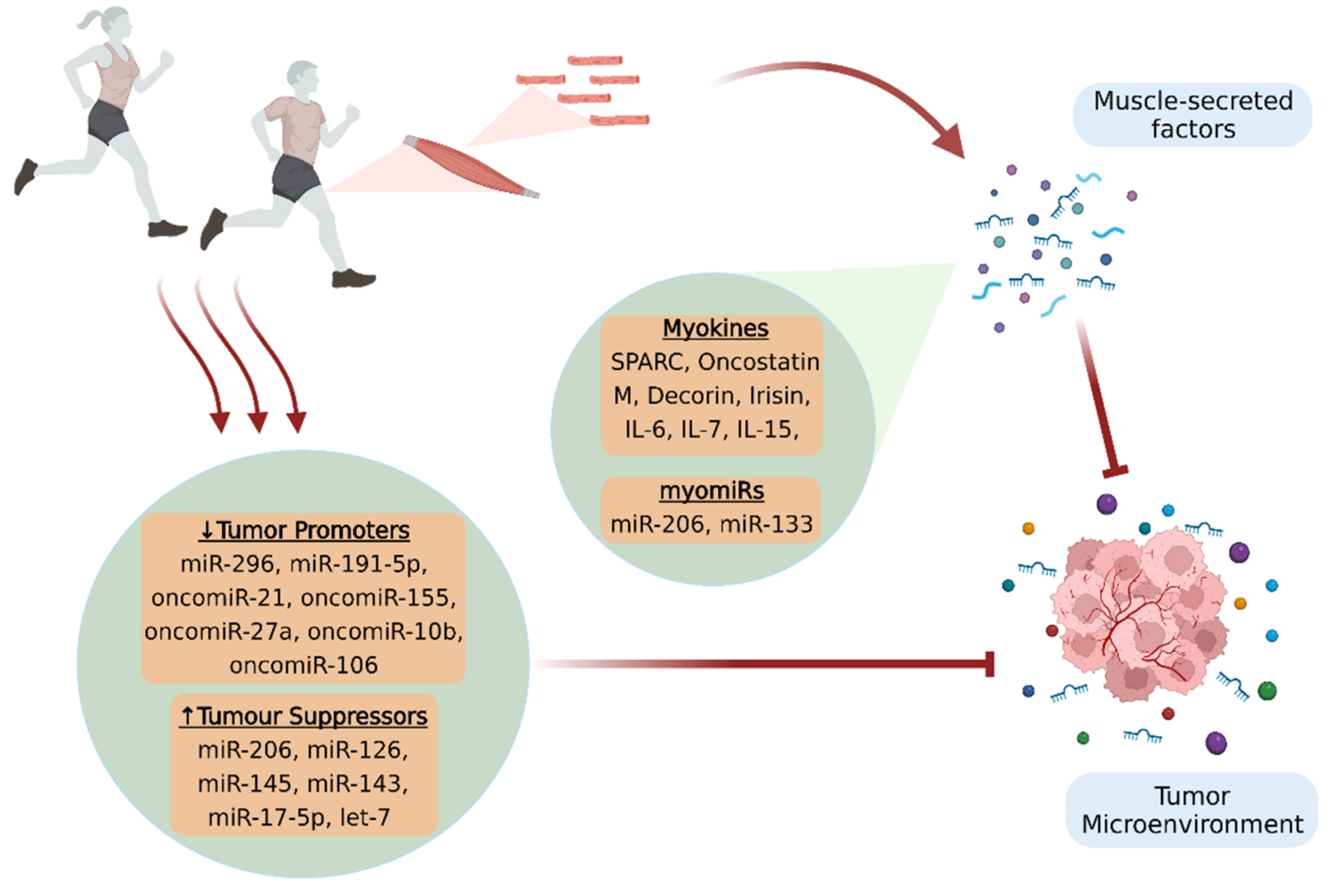

A growing body of in vitro and in vivo studies suggests that physical activity offers important benefits against cancer, in terms of both prevention and treatment. However, the exact mechanisms implicated in the anticancer effects of exercise remain to be further elucidated. Muscle-secreted factors in response to contraction have been proposed to mediate the physical exercise-induced beneficial effects and be responsible for the inter-tissue communications. Specifically, myokines and microRNAs (miRNAs) constitute the most studied components of the skeletal muscle secretome that appear to affect the malignancy, either directly by possessing antioncogenic properties, or indirectly by mobilizing the antitumor immune responses. Moreover, some of these factors are capable of mitigating serious, disease-associated adverse effects that deteriorate patients’ quality of life and prognosis. The present review summarizes the myokines and miRNAs that may have potent anticancer properties and the expression of which is induced by physical exercise, while the mechanisms of secretion and intercellular transportation of these factors are also discussed.

- physical activity

- exercise

- muscle-derived factors

- cancer

- myokines

- miRNAs

- microRNAs

- cancer progression

1. Introduction

2. Myokines

2.1. Myokines and Cancer Progression

Given that adequate research data supporting a direct association between myokines and tumor growth are still lacking, SPARC is one of the most studied myokines in cancer [29][23]. SPARC, also known as osteonectin, is a matricellular protein implicated in the interactions of cells with the extracellular matrix (ECM) [30,31][24][25]. It has been found that SPARC is secreted from skeletal muscle into circulation after a single bout of exercise in healthy humans, but also in rodents with colon cancer. Moreover, it has been showed that regular exercise suppressed colon tumorigenesis in mice, while the anti-tumor effect of exercise was abolished in SPARC knockout mice [32,33][26][27]. These findings are in agreement with other studies that revealed increased SPARC expression in both physically active mice and humans, as well as a better overall survival in patients with digestive tract cancer who exhibited a higher than the median level of SPARC [34][28]. Furthermore, evidence from both in vitro and in vivo studies supports the notion that oncostatin M (OSM), a cytokine belonging to the IL-6 family [35[29][30],36], possibly mediates some of the inhibitory effects of exercise against cancer evolution. Indeed, it has been reported that the incubation of human breast cancer cells with a post-exercise human serum containing OSM inhibited cell proliferation and induced apoptosis, while the blockage of OSM mitigated the anti-tumor effects of exercise-conditioned serum [9]. The role of OSM as a myokine was further verified, as a single exercise bout resulted not only in the upregulation of OSM in skeletal muscles, but also in its increased secretion into the circulation [9]. Moreover, animal studies have confirmed that aerobic exercise exhibits its protective effects against cancer through OSM, resulting in decreased tumor volumes in tumor-bearing mice [37,38][31][32].2.2. Myokines and Cancer-Associated Sarcopenia

Cancer-associated sarcopenia consists a severe muscle wasting syndrome manifesting in various cancer types, and it not only deteriorates patients’ functional ability and quality of life but can also lead to cancer death [64,65][33][34]. Sarcopenia may appear in cancer patients as a side effect of the systemic cytotoxic chemotherapies, or as a consequence of the tumor-secreted factors that disrupt skeletal muscle homeostasis and lead to increased proteolysis and suppressed protein synthesis [64][33]. In particular, selective atrophy of type 2 fibers with a fast-to-slow fiber type shift has been described in cachectic cancer patients [66][35]. In this context, physical exercise plays a pivotal role in maintaining skeletal muscle mass through the secretion of various myokines during muscle contraction [65][34]. Specifically, IL-6, whose anticarcinogenic properties have been already discussed, increases acutely after an exercise bout in both healthy subjects and cancer patients [67][36]. One of the essential muscle mass-related features of IL-6 is that it facilitates the proliferation, differentiation, and fusion of satellite cells by activating or regulating the respective JAK/STAT, p38/MAPK, and NF-κB signaling pathways. Thus, the involvement of IL-6 in satellite cell-dependent myogenesis can promote skeletal muscle protein synthesis and hypertrophy and ameliorate cancer-related muscle wasting [52,68][37][38].3. Circulating microRNAs and MyomiRs

MiRNAs are a class of endogenous, single-stranded, non-coding RNAs with a length of 18–22 ribonucleotides [87,88,89,90,91][39][40][41][42][43]. MiRNAs cannot be translated into proteins, but rather they control post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression through cleavage, destabilization, or less efficient translation of coding mRNAs [92][44]. It has been well documented that the binding of miRNAs to the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTR) of their target genes alters their expression [88,91][40][43] and plays a vital role in the regulation of numerous physiological processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and metabolism [87,88,89,90][39][40][41][42]. Indeed, adequate evidence suggested that either the elevated or decreased levels of particular miRNAs are involved in a variety of human diseases, including cancer [90][42]. Specifically, the expression of specific miRNAs can lead to tumor suppression through the downregulation of oncogenes or the upregulation of tumor suppressing genes, while conversely the overexpression of other miRNAs, called oncomiRs, promotes oncogenesis [87,92][39][44]. For instance, miR-152 acts as a tumor suppressor in ovarian, gastric, and liver cancer, implicated in the inhibition of cell proliferation, invasion, and migration [93][45]. On the other hand, miR-24 has been identified as an oncomiR responsible for the bad prognosis of various types of non-solid and solid cancers, including leukemia and breast, liver, and lung cancer [94,95,96,97][46][47][48][49]. Even though the majority of miRNAs is expressed in numerous tissues, some of them are considered as tissue-specific, since they are transcribed as much as 20 times higher in specific cell types, compared with their expression levels in other tissues. In particular, myomiRs consist of a subcategory of miRNAs that are striated muscle-specific and are expressed in higher levels in skeletal and/or cardiac muscle [98][50]. Moreover, miRNAs are not detected exclusively in tissues and organs, but they can also be released into circulation (c-miRNAs), travel through the human body, and impact key cellular processes. Thus, while multiple c-miRNAs are associated with either carcinogenesis, tumor suppression, DNA repair, or checkpoint functions, they could also be potential mediators of the benefits that regular physical activity induces towards the regulation of cancer development and progression [92][44].3.1. MyomiRs and Cancer Progression

MyomiR-133 is a circulating miRNA that not only influences myoblast differentiation but also contributes to the suppression of several tumors, such as ovarian, breast, prostate, gastric, bladder, pituitary, glioma, and colorectal cancer [99,100,101,102,103][51][52][53][54][55]. In this context, it has been shown that both acute and chronic exercise increases the intramuscular expression and the subsequent release of myomiR-133 into circulation, which subsequently impacts cancer progression by targeting crucial oncogenes, such as IGF-1R and EGFR [104,105,106][56][57][58]. These growth factor receptors interact with the PI3K/Akt and the MAPK/ERK signaling pathways, which orchestrate core cellular functions such as proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. Consequently, the upregulation of myo-miR-133 can abrogate cancer-associated hallmarks, such as aberrant cell migration and invasion, thus restraining cancer evolution [107][59].3.2. MicroRNAs Regulated by Exercise

Recent evidence suggests that 45 min of aerobic exercise can acutely modify the expression of 14 c-miRNAs, which are involved in cancer pathways [111][60]. In particular, myomiR-206, a regulator of cancer cell proliferation and migration that plays an anti-cancer role in cancer progression [112[61][62],113], exhibited greater expression changes after aerobic exercise [111][60]. Cancer progression could be also influenced by the exercise-induced regulation of miR-296 and miR-126 expression in breast cancer. A 10-week aerobic exercise program in tumor-bearing mice led to decreased tumor growth mediated by the downregulation of the pro-angiogenic miR-296 and the upregulation of the anti-angiogenic miR-126 [118][63].4. Intercellular Transport and Delivery of Muscle-Secreted Biomolecules: The Role of Exosomes

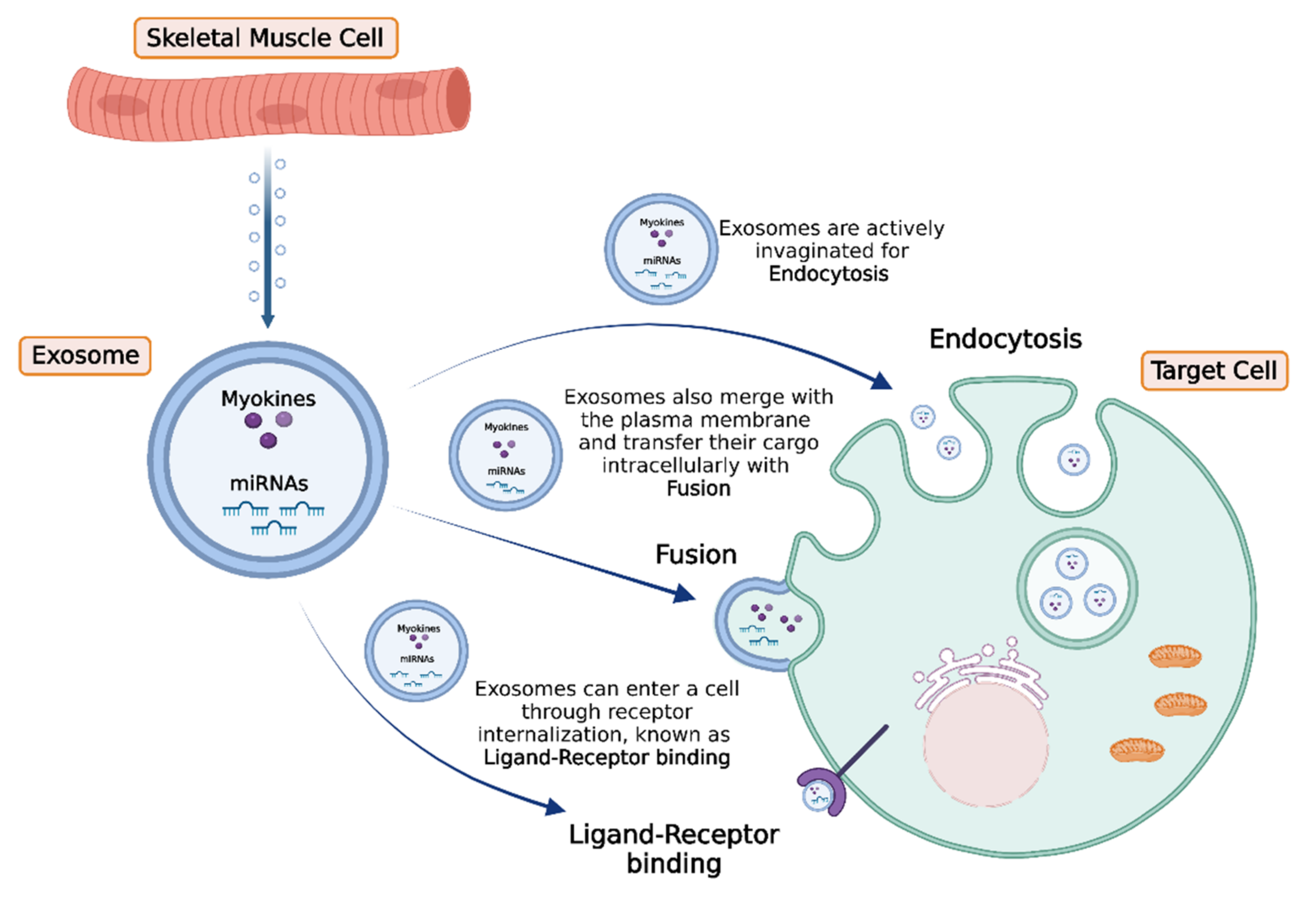

Communication between different cell types and tissues is of vital importance both in health and disease, and skeletal muscle cells effectuate this process in a direct or indirect manner. Specifically, the bioactive molecules secreted by skeletal myocytes may act locally in a paracrine or autocrine manner, or they can be secreted into the circulation and travel and migrate through the body, acting in an endocrine manner. In general, autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine regulatory systems include active forms of secretion and transport of molecules that require energy expenditure, as well as the passive transport of substances across cell membranes without using cell energy [131][64]. Typically, in the framework of active intercellular communication, the formation of transport vesicles derived from the endoplasmic reticulum and subsequently from the Golgi apparatus is a common process for targeted substance trafficking [132][65]. These structures are called extracellular vesicles (EV) and enable the physiological translocation of molecules such as enzymes, cytokines, and miRNAs, which otherwise could not exit the cytosol and be released in the extracellular space or enter the circulation. In general, EVs are divided in three main categories according to their diameter: the exosomes (30 to 150 nm), the microvesicles (about 1 μm), and the apoptotic bodies (1 to 5 μm) [133,134][66][67]. The primary cellular process that mediates the exchange of bioactive molecules is exocytosis, which in cooperation with endocytosis, membrane fusion, and receptor–ligand binding, enables their uptake from target cells [135][68]. Recently, it has been revealed that upon exercise stimuli, skeletal muscle cells release EVs to exert significant effects either to adjacent or distant tissues [42,136][69][70] (Figure 2). More specifically, myokines, along with other peptides, chemokines, and hormones, can be packed in specialized vesicles, the exosomes, the biogenesis of which requires the invagination of the plasma membrane to form an early endosome. Subsequently, the early endosome buds into the surrounding lumina, leading to the formation of many small intraluminal vesicles (ILVs), a complex called multivesicular bodies (MVBs), or late endosomes. If MVBs are not deconstructed, they merge to the plasma membrane to be released in the extracellular space as exosomes. Interestingly, studies performed in differentiated myocytes suggest that skeletal muscle may be able to facilitate cell-to-cell signaling through exosomes independently of MVBs, but by the direct release of exosomes through the plasma membrane [137][71].

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

References

- Maridaki, M.; Papadopetraki, A.; Karagianni, H.; Koutsilieris, M.; Philippou, A. The Assessment and Relationship between Quality of Life and Physical Activity Levels in Greek Breast Cancer Female Patients under Chemotherapy. Sports 2020, 8, 32.

- Pedersen, B.K.; Saltin, B. Exercise as medicine-evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 25, 1–72.

- Hoffmann, C.; Weigert, C. Skeletal Muscle as an Endocrine Organ: The Role of Myokines in Exercise Adaptations. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2017, 7, a029793.

- Soares-Miranda, L.; Lucia, A.; Silva, M.; Peixoto, A.; Ramalho, R.; da Silva, P.C.; Mota, J.; Macedo, G.; Abreu, S. Physical Fitness and Health-related Quality of Life in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Sports Med. 2021, 42, 924–929.

- Philippou, A.; Papadopetraki, A.; Maridaki, M.; Koutsilieris, M. Exercise as Complementary Therapy for Cancer Patients during and after Treatment. Sports Med. 2020, 1, 1–24.

- Severinsen, M.C.K.; Pedersen, B.K. Muscle-Organ Crosstalk: The Emerging Roles of Myokines. Endocr. Rev. 2020, 41, 594–609.

- Orman, A.; Johnson, D.L.; Comander, A.; Brockton, N. Breast Cancer: A Lifestyle Medicine Approach. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2020, 14, 483–494.

- Koelwyn, G.J.; Quail, D.F.; Zhang, X.; White, R.M.; Jones, L.W. Exercise-dependent regulation of the tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 620–632.

- Hojman, P.; Dethlefsen, C.; Brandt, C.; Hansen, J.; Pedersen, L.; Pedersen, B.K. Exercise-induced muscle-derived cytokines inhibit mammary cancer cell growth. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 301, E504–E510.

- Adraskela, K.; Veisaki, E.; Koutsilieris, M.; Philippou, A. Physical Exercise Positively Influences Breast Cancer Evolution. Clin. Breast Cancer 2017, 17, 408–417.

- Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, J.; Tzanninis, J.G.; Philippou, A.; Koutsilieris, M. Epigenetic regulation on gene expression induced by physical exercise. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2013, 13, 133–146.

- Seldin, M.M.; Wong, G.W. Regulation of tissue crosstalk by skeletal muscle-derived myonectin and other myokines. Adipocyte 2012, 1, 200–202.

- Yoshikawa, M.; Nakasa, T.; Ishikawa, M.; Adachi, N.; Ochi, M. Evaluation of autologous skeletal muscle-derived factors for regenerative medicine applications. Bone Jt. Res. 2017, 6, 277–283.

- Hong, B.S. Regulation of the Effect of Physical Activity Through MicroRNAs in Breast Cancer. Int. J. Sports Med. 2021.

- Durzynska, J.; Philippou, A.; Brisson, B.K.; Nguyen-McCarty, M.; Barton, E.R. The pro-forms of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) are predominant in skeletal muscle and alter IGF-I receptor activation. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 1215–1224.

- Philippou, A.; Barton, E.R. Optimizing IGF-I for skeletal muscle therapeutics. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2014, 24, 157–163.

- Bikle, D.D.; Tahimic, C.; Chang, W.; Wang, Y.; Philippou, A.; Barton, E.R. Role of IGF-I signaling in muscle bone interactions. Bone 2015, 80, 79–88.

- Pedersen, L.; Hojman, P. Muscle-to-organ cross talk mediated by myokines. Adipocyte 2012, 1, 164–167.

- Lightfoot, A.; Cooper, R.G. The role of myokines in muscle health and disease. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2016, 28, 661–666.

- Schnyder, S.; Handschin, C. Skeletal muscle as an endocrine organ: PGC-1alpha, myokines and exercise. Bone 2015, 80, 115–125.

- Dalamaga, M. Interplay of adipokines and myokines in cancer pathophysiology: Emerging therapeutic implications. World J. Exp. Med. 2013, 3, 26–33.

- Buss, L.A.; Dachs, G.U. Effects of Exercise on the Tumour Microenvironment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1225, 31–51.

- Garneau, L.; Parsons, S.A.; Smith, S.R.; Mulvihill, E.E.; Sparks, L.M.; Aguer, C. Plasma Myokine Concentrations After Acute Exercise in Non-obese and Obese Sedentary Women. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 18.

- Bedore, J.; Leask, A.; Séguin, C.A. Targeting the extracellular matrix: Matricellular proteins regulate cell-extracellular matrix communication within distinct niches of the intervertebral disc. Matrix Biol. 2014, 37, 124–130.

- Liu, Y.-P.; Hsiao, M. Exercise-induced SPARC prevents tumorigenesis of colon cancer. Gut 2013, 62, 810–811.

- Aoi, W.; Naito, Y.; Takagi, T.; Tanimura, Y.; Takanami, Y.; Kawai, Y.; Sakuma, K.; Hang, L.P.; Mizushima, K.; Hirai, Y.; et al. A novel myokine, secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC), suppresses colon tumorigenesis via regular exercise. Gut 2013, 62, 882–889.

- Matsuo, K.; Sato, K.; Suemoto, K.; Miyamoto-Mikami, E.; Fuku, N.; Higashida, K.; Tsuji, K.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Iemitsu, M.; et al. A Mechanism Underlying Preventive Effect of High-Intensity Training on Colon Cancer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 1805–1816.

- Akutsu, T.; Ito, E.; Narita, M.; Ohdaira, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Urashima, M. Effect of Serum SPARC Levels on Survival in Patients with Digestive Tract Cancer: A Post Hoc Analysis of the AMATERASU Randomized Clinical Trial. Cancers 2020, 12, 1465.

- Hermanns, H.M. Oncostatin M and interleukin-31: Cytokines, receptors, signal transduction and physiology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2015, 26, 545–558.

- Won Seok Hyung, W.; Gon Lee, S.; Tae Kim, K.; Soo Kim, H. Oncostatin M, a muscle-secreted myokine, recovers high-glucose-induced impairment of Akt phosphorylation by Fos induction in hippocampal neuron cells. Neuroreport 2019, 30, 765–770.

- Manzari Tavakoli, Z.; Amani Shalamzari, S.; Kazemi, A. Effects of 6 weeks’ Endurance Training on Oncostatin-M in Muscle and Tumor Tissues in mice with Breast Cancer. Iran. J. Breast Dis. 2017, 9, 50–59.

- Molanouri Shamsi, M.; Chekachak, S.; Soudi, S.; Gharakhanlou, R.; Quinn, L.S.; Ranjbar, K.; Rezaei, S.; Shirazi, F.J.; Allahmoradi, B.; Yazdi, M.H.; et al. Effects of exercise training and supplementation with selenium nanoparticle on T-helper 1 and 2 and cytokine levels in tumor tissue of mice bearing the 4 T1 mammary carcinoma. Nutrition 2019, 57, 141–147.

- Siff, T.; Parajuli, P.; Razzaque, M.S.; Atfi, A. Cancer-Mediated Muscle Cachexia: Etiology and Clinical Management. Trends. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 32, 382–402.

- Webster, J.M.; Kempen, L.; Hardy, R.S.; Langen, R.C.J. Inflammation and Skeletal Muscle Wasting During Cachexia. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 597675.

- Ciciliot, S.; Rossi, A.C.; Dyar, K.A.; Blaauw, B.; Schiaffino, S. Muscle type and fiber type specificity in muscle wasting. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 45, 2191–2199.

- Galvao, D.A.; Nosaka, K.; Taaffe, D.R.; Peake, J.; Spry, N.; Suzuki, K.; Yamaya, K.; McGuigan, M.R.; Kristjanson, L.J.; Newton, R.U. Endocrine and immune responses to resistance training in prostate cancer patients. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2008, 11, 160–165.

- Daou, H.N. Exercise as an anti-inflammatory therapy for cancer cachexia: A focus on interleukin-6 regulation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2020, 318, R296–R310.

- Hoene, M.; Runge, H.; Haring, H.U.; Schleicher, E.D.; Weigert, C. Interleukin-6 promotes myogenic differentiation of mouse skeletal muscle cells: Role of the STAT3 pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013, 304, C128–C136.

- Cui, M.; Yao, X.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, D.; Cui, R.; Zhang, X. Interactive functions of microRNAs in the miR-23a-27a-24-2 cluster and the potential for targeted therapy in cancer. J. Cell Physiol. 2020, 235, 6–16.

- Tan, Z.; Jia, J.; Jiang, Y. MiR-150-3p targets SP1 and suppresses the growth of glioma cells. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38, BSR20180019.

- Ling, H.; Fabbri, M.; Calin, G.A. MicroRNAs and other non-coding RNAs as targets for anticancer drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 847–865.

- Chen, H.; Gao, S.; Cheng, C. MiR-323a-3p suppressed the glycolysis of osteosarcoma via targeting LDHA. Hum. Cell 2018, 31, 300–309.

- Gareev, I.; Beylerli, O.; Yang, G.; Sun, J.; Pavlov, V.; Izmailov, A.; Shi, H.; Zhao, S. The current state of MiRNAs as biomarkers and therapeutic tools. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 20, 349–359.

- Dufresne, S.; Rebillard, A.; Muti, P.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Brenner, D.R. A Review of Physical Activity and Circulating miRNA Expression: Implications in Cancer Risk and Progression. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2018, 27, 11–24.

- Kong, S.; Fang, Y.; Wang, B.; Cao, Y.; He, R.; Zhao, Z. miR-152-5p suppresses glioma progression and tumorigenesis and potentiates temozolomide sensitivity by targeting FBXL7. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 4569–4579.

- Khodadadi-Jamayran, A.; Akgol-Oksuz, B.; Afanasyeva, Y.; Heguy, A.; Thompson, M.; Ray, K.; Giro-Perafita, A.; Sanchez, I.; Wu, X.; Tripathy, D.; et al. Prognostic role of elevated mir-24-3p in breast cancer and its association with the metastatic process. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 12868–12878.

- Yang, Y.; Song, S.; Meng, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Xie, S.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wang, C.; Lu, Y.; et al. miR24-2 accelerates progression of liver cancer cells by activating Pim1 through tri-methylation of Histone H3 on the ninth lysine. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 2772–2790.

- Organista-Nava, J.; Gomez-Gomez, Y.; Illades-Aguiar, B.; del Carmen Alarcon-Romero, L.; Saavedra-Herrera, M.V.; Rivera-Ramirez, A.B.; Garzon-Barrientos, V.H.; Leyva-Vazquez, M.A. High miR-24 expression is associated with risk of relapse and poor survival in acute leukemia. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 1639–1649.

- Yan, L.; Ma, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zan, J.; Wang, Z.; Ling, L.; Li, Q.; Lv, J.; Qi, S.; Cao, Y.; et al. miR-24-3p promotes cell migration and proliferation in lung cancer by targeting SOX7. J. Cell Biochem. 2018, 119, 3989–3998.

- Siracusa, J.; Koulmann, N.; Banzet, S. Circulating myomiRs: A new class of biomarkers to monitor skeletal muscle in physiology and medicine. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2018, 9, 20–27.

- Li, D.; Xia, L.; Chen, M.; Lin, C.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, S.; Li, X. miR-133b, a particular member of myomiRs, coming into playing its unique pathological role in human cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 50193–50208.

- Liu, Y.; Han, L.; Bai, Y.; Du, W.; Yang, B. Down-regulation of MicroRNA-133 predicts poor overall survival and regulates the growth and invasive abilities in glioma. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 206–210.

- Chen, X.B.; Li, W.; Chu, A.X. MicroRNA-133a inhibits gastric cancer cells growth, migration, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition process by targeting presenilin 1. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 470–480.

- Guo, J.; Xia, B.; Meng, F.; Lou, G. miR-133a suppresses ovarian cancer cell proliferation by directly targeting insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. Tumour. Biol. 2014, 35, 1557–1564.

- Wang, D.S.; Zhang, H.Q.; Zhang, B.; Yuan, Z.B.; Yu, Z.K.; Yang, T.; Zhang, S.Q.; Liu, Y.; Jia, X.X. miR-133 inhibits pituitary tumor cell migration and invasion via down-regulating FOXC1 expression. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15, gmr.15017453.

- Li, F.; Bai, M.; Xu, J.; Zhu, L.; Liu, C.; Duan, R. Long-Term Exercise Alters the Profiles of Circulating Micro-RNAs in the Plasma of Young Women. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 372.

- Gong, Y.; Ren, J.; Liu, K.; Tang, L.M. Tumor suppressor role of miR-133a in gastric cancer by repressing IGF1R. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 2949–2958.

- Xu, F.; Li, F.; Zhang, W.; Jia, P. Growth of glioblastoma is inhibited by miR-133-mediated EGFR suppression. Tumour. Biol. 2015, 36, 9553–9558.

- Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, T.; Chen, H. MicroRNA-133 inhibits the growth and metastasis of the human lung cancer cells by targeting epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Buon 2019, 24, 929–935.

- Pulliero, A.; You, M.; Chaluvally-Raghavan, P.; Marengo, B.; Domenicotti, C.; Banelli, B.; Degan, P.; Molfetta, L.; Gianiorio, F.; Izzotti, A. Anticancer effect of physical activity is mediated by modulation of extracellular microRNA in blood. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 2106–2119.

- Rahimi, M.; Sharifi-Zarchi, A.; Zarghami, N.; Geranpayeh, L.; Ebrahimi, M.; Alizadeh, E. Down-Regulation of miR-200c and Up-Regulation of miR-30c Target both Stemness and Metastasis Genes in Breast Cancer. Cell J. 2020, 21, 467–478.

- Yen, M.C.; Shih, Y.C.; Hsu, Y.L.; Lin, E.S.; Lin, Y.S.; Tsai, E.M.; Ho, Y.W.; Hou, M.F.; Kuo, P.L. Isolinderalactone enhances the inhibition of SOCS3 on STAT3 activity by decreasing miR-30c in breast cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35, 1356–1364.

- Nasiri, M.; Peeri, M.; Matinhomaei, H. Endurance Training Attenuates Angiogenesis Following Breast Cancer by Regulation of MiR-126 and MiR-296 in Breast Cancer Bearing Mice. Int. J. Cancer Manag. 2017, in press.

- Yang, N.J.; Hinner, M.J. Getting across the cell membrane: An overview for small molecules, peptides, and proteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1266, 29–53.

- Barlowe, C.; Helenius, A. Cargo Capture and Bulk Flow in the Early Secretory Pathway. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 32, 197–222.

- Trovato, E.; di Felice, V.; Barone, R. Extracellular Vesicles: Delivery Vehicles of Myokines. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 522.

- Manou, D.; Caon, I.; Bouris, P.; Triantaphyllidou, I.E.; Giaroni, C.; Passi, A.; Karamanos, N.K.; Vigetti, D.; Theocharis, A.D. The Complex Interplay Between Extracellular Matrix and Cells in Tissues. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1952, 1–20.

- Yue, B.; Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Ru, W.; Wu, J.; Huang, Y.; Lan, X.; Lei, C.; Chen, H. Exosome biogenesis, secretion and function of exosomal miRNAs in skeletal muscle myogenesis. Cell Prolif. 2020, 53, e12857.

- Whitham, M.; Febbraio, M.A. The ever-expanding myokinome: Discovery challenges and therapeutic implications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 719–729.

- Bei, Y.; Xu, T.; Lv, D.; Yu, P.; Xu, J.; Che, L.; Das, A.; Tigges, J.; Toxavidis, V.; Ghiran, I.; et al. Exercise-induced circulating extracellular vesicles protect against cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2017, 112, 38.

- Romancino, D.P.; Paterniti, G.; Campos, Y.; de Luca, A.; di Felice, V.; d’Azzo, A.; Bongiovanni, A. Identification and characterization of the nano-sized vesicles released by muscle cells. FEBS Lett. 2013, 587, 1379–1384.

- Moustogiannis, A.; Philippou, A.; Zevolis, E.; Taso, O.; Chatzigeorgiou, A.; Koutsilieris, M. Characterization of Optimal Strain, Frequency and Duration of Mechanical Loading on Skeletal Myotubes’ Biological Responses. Vivo 2020, 34, 1779–1788.