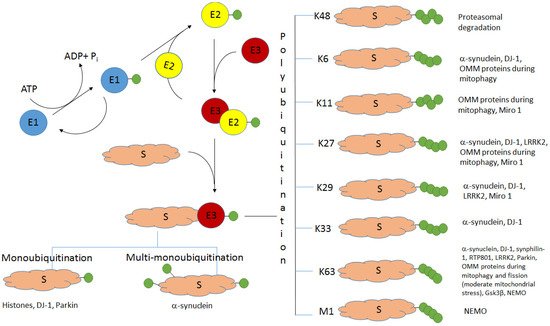

2. Alpha-Synuclein and Histones: Monoubiquitination and Multi-Monoubiquitination

A typical feature of many neurodegenerative diseases is the accumulation of protein aggregates, and PD is not an exception

[23][37]. The main component of Lewy bodies, alpha-synuclein

[24][25][38,39], was shown to be subjected to monoubiquitination before its proteasomal degradation

[26][40]. Although K48-linked polyubiquitination has been initially considered as a canonical targeting of proteins for their consequent proteasomal degradation, it becomes clear that about 40% of mammalian proteins, cleaved by proteasomes, are monoubiquitinated

[27][28][41,42]. Alpha-synuclein has been shown to be monoubiquitinated by the E3 ubiquitin ligase SIAH (seven in absentia homolog) both in vivo and in vitro

[29][30][31][43,44,45]. The ubiquitination at certain lysine residues induces structural changes in alpha-synuclein aggregates in vitro

[32][46]. Synphilin-1A, an isoform of synphilin-1 (another component of Lewy bodies), inhibits alpha-synuclein monoubiquitination by SIAH and the formation of alpha-synuclein inclusions

[33][47]. Rott et al. found that the deubiquitinase USP9X (downregulated in the PD substantia nigra) specifically deubiquitinates alpha-synuclein in vivo and in vitro

[26][40]. Moreover, site-specific monoubiquitination provides different levels of alpha-synuclein degradation

[34][48]. In contrast to monoubiquitinated alpha-synuclein, which undergoes proteasomal degradation, deubiquitinated alpha-synuclein is eliminated by autophagy

[26][40]. Thus, USP9X regulates the degradation of alpha-synuclein

[26][35][40,49]. Although it remains unclear whether protein aggregates are the cause of neuronal toxicity or the adaptation of neurons to the accumulation of toxic proteins

[36][50], therapy modulating activity of the investigated enzymes may be a successful strategy to treat alpha-synucleinopathies.

In the context of (pathological) protein aggregate formation, it should be noted that alpha-synuclein may form complexes with histones, protein components of chromatin, which play a key role in many cellular events

[37][51].

Moreover, it has long been known that histones may be also monoubiquitinated

[38][39][55,56], and histone monoubiquitination is essential for many biological pathways: transcriptional regulation

[40][41][42][43][57,58,59,60], differentiation

[44][27], cell cycle regulation

[45][61], and DNA damage response

[46][47][62,63]. Monoubiquitination of histone H2B is involved in almost all these processes

[48][49][64,65]. The role of dysregulation of histone monoubiquitination in cancer progression is well known

[50][66], but its role in neurodegeneration is also important. Permanent oxidative stress causes nuclear and mitochondrial DNA damage; PD and other neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by defective DNA repair

[51][52][67,68].

Monoubiquitination of histone H2A, one of the main components of chromatin and a major histone modification in mammalian cells

[53][54][71,72], is crucial for neurodevelopmental disorders

[42][59]. Histones are involved in the formation of inclusions, typical of neurodegenerative diseases, such as PD, Huntington’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease

[46][55][62,73]. Ubiquitin conjugates accumulate on the inclusion bodies, and this correlates with the depletion of ubiquitin from the nucleus, deubiquitination of histones H2A and H2B, and subsequent DNA damage

[46][62].

3. Atypical Ubiquitination of the Components of Lewy Bodies: Alpha-Synuclein, DJ-1, and Synphilin-1

3.1. E3 Ubiquitin Ligase TRAF6: K6, K27, and K29 Ubiquitination of Alpha-Synuclein

Besides monoubiquitination, atypical polyubiquitination is characteristic of alpha-synuclein. It was shown that both mutant (PD-associated) and wild-type alpha-synucleins specifically interacted with the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF6 (tumor necrosis factor-receptor associated factor 6) and were subjected to AU via K6, K27, and K29 chains

[56][82].

3.2. Concerted Action of the E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Parkin with the E2 Enzyme UbcH13/Uev1a: K63-Linked Ubiquitination of Alpha-Synuclein and Synphilin-1 Promotes Lewy Body Formation

The heterodimer E2 complex UbcH13/Uev1a is known to mediate K63-linked polymerization of ubiquitin. Doss-Pepe et al. have shown that parkin can function in cooperation with UbcH13/Uev1a to assemble ubiquitin-K63 chain, and alpha-synuclein can stimulate the assembly of these chains

[57][83]. The parkin-mediated K63-linked ubiquitination of alpha-synuclein and another component of Lewy bodies, synphilin-1, contributed to the formation of synuclein/synphilin-1 inclusions

[58][84]. Thus, K63-linked ubiquitination of alpha-synuclein and synphilin-1 could be considered as an important prerequisite for the formation of Lewy bodies

[59][85].

3.3. HECT E3 Ligase NEDD4: K63-Linked Ubiquitination of Alpha-Synuclein

The ubiquitin ligase Nedd4 catalyzes K63-linked ubiquitination of alpha-synuclein. In vitro experiments with full-length alpha-synuclein and its recombinant fragments, lacking either the N-terminal or C-terminal residues, have shown the importance of the C-terminal residues (120–140) containing several prolines. The Nedd4 substrate interacting domain, exhibiting affinity to proline-rich motifs, bound the C-terminal region of alpha-synuclein and attached K63-linked ubiquitin chains

[60][86]. Interestingly, the other three purified recombinant E3 ligases, implicated in alpha-synuclein degradation (CHIP, SIAH2, and parkin), were catalytically active but ineffective in alpha-synuclein ubiquitination in this in vitro system, containing either UbcH5 or UbcH7 as the E2 component

[60][86]. In cells (over)expressing Nedd4, alpha-synuclein content decreased. The treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with selective inhibitors of proteasomes, lysosomes, and autophagy caused a 2-fold increase in alpha-synuclein content, thus suggesting several routes of alpha-synuclein degradation. Mapping the subcellular distribution of alpha-synuclein, overexpressed in neurons, revealed its association with the protein degradation pathway, including multivesicular bodies in the axons and the lysosomes within neuronal cell bodies

[61][87]. Later, the endosomal pathway of alpha-synuclein sequestration, involving Lys-63-linked ubiquitination by the E3 ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-1, was demonstrated not only for de novo synthesized alpha-synuclein but also for internalized alpha-synuclein

[62][88].

3.4. DJ-1: Monoubiquitination and K63-Linked Polyubiquitination. DJ-1 and Alpha-Synuclein: K6-, K27-, and K29-Linked Polyubiquitination

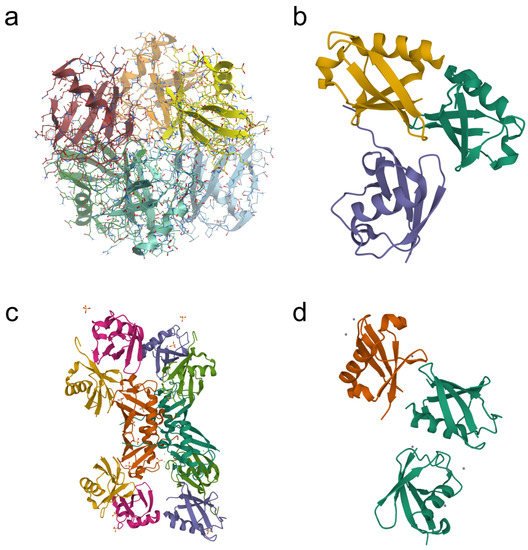

DJ-1, also known as Parkinson disease protein 7, is a multifunctional protein ubiquitously expressed in cells and tissues and exhibiting both catalytic (as protein deglycase, EC 3.5.1.124) and numerous noncatalytic activities

[63][64][65][93,94,95].

In cells, DJ-1 normally exists as a dimer, while its mutant forms containing amino acid substitutions, typical of PD, are characterized by impaired dimerization ability, stability, and folding

[66][96]. The amino acid substitution L166P has the most pronounced devastating effect on the DJ-1 structure, folding, and homodimerization

[67][97]. Being detected in the cytoplasm, DJ-1 may be translocated into mitochondria and the nucleus. In mitochondria, DJ-1 interacts with NADH dehydrogenase and ATP synthase subunits and plays an important role in the functional integrity of the inner mitochondrial membrane. In the nucleus, DJ-1 functions as a histone deglycase

[68][98] and interacts with (and sequesters) the Daxx protein, thus preventing cell death

[69][99]. DJ-1 has been also recognized as a coactivator of various signaling pathways of the androgen receptor

[70][71][100,101], Nrf2

[72][102], and p53 protein

[73][74][103,104]. It is also essential for transcriptional activation of the tyrosine hydroxylase gene, encoding the key enzyme of dopamine synthesis

[75][76][105,106]. The biological activity of DJ-1 may be regulated by small ubiquitin-like modifiers (SUMOs)

[77][78][107,108]. In cells, wild-type DJ-1 undergoes sumoylation at the lysine residue (K130); in the case of the L166P mutation associated with the development of PD, sumoylation occurred at other lysine residues with the formation of misfolded insoluble forms of the protein

[77][107].

In neuroblastoma cells and in human brain lysates, DJ-1 forms a complex with parkin and PINK1

[79][109]. This complex has ubiquitin ligase activity, which ubiquitinates parkin substrates (for example, synphilin-1) and parkin itself

[79][109]. However, parkin does not ubiquitinate wild-type DJ-1

[80][110]. Genetic depletion of DJ-1 or PINK1 decreased the ubiquitination level of parkin and its substrates and caused the accumulation of aberrant proteins.

DJ-1 may also interact with another E3 ubiquitin ligase

[81][111] known as a tumor suppressor, VHL (von Hippel–Lindau) protein

[82][83][112,113]. This interaction impairs VHL interaction with the alpha subunit of the heterodimeric hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1 (HIF-1alpha) and prevents the ubiquitination of HIF-1alpha. DJ-1 deficiency leads to a decrease in the HIF-1alpha level during hypoxia and oxidative stress. Lymphoblasts of patients with PD, associated with DJ-1 mutations, are characterized by less stable HIF-1alpha compared to that in healthy people. This suggests that DJ-1 protects neurons from death by inhibiting the VHL ubiquitin ligase activity

[81][111].

4. LRRK2: K63- and K27-Linked Ubiquitination

Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), a member of the leucine-rich kinase family, is a multifunctional protein kinase containing a GTPase domain. Mutations in the corresponding gene (

LRRK2, also known as

PARK8) are linked to the most common familial forms and some sporadic forms of PD, and small-molecule inhibitors of LRRK2 attract much interest in the context of PD therapy

[84][85][86][120,121,122].

LRRK2 is a substrate for the carboxyl terminus of HSP70-interacting protein (CHIP) known as CHIP E3 ligase, which regulates the steady-state level of LRRK2 via UPS degradation

[87][123]. The LRRK2 level was significantly (4-fold) higher in the soluble fraction of the brains of CHIP knockout mice than in control wild-type mice

[87][123]. The cells treated with a CHIP siRNA exhibited a higher level of LRRK2 (by 20–25%), while the cells exposed to the wild-type CHIP were characterized by a detectable decrease in the LRRK2 level (20–25%)

[87][123]. Although the type of LRRK2 ubiquitination by CHIP has not been investigated, studies with other protein targets indicate that CHIP enhances K63-linked ubiquitination

[88][124]. CHIP-dependent ubiquitination of LRRK2 involves interactions with several heat shock proteins

[87][88][123,124], particularly HSP90, which is one of the three key players (together with DJ-1 and SOD2) forming a single network of brain ubiquitinated proteins

[89][115]. The 20S proteasome inhibitor, clasto-lactacystin beta-lactone, increased the level of ubiquitinated LRRK2 in HEK293 cells, while CHIP overexpression in SH-SY5Y cells attenuated the toxicity of G2019S and R1441C LRRK2 mutants

[87][123].

The other E3 ubiquitin ligase WSB1 (WD repeat and SOCS box-containing protein 1) could ubiquitinate LRRK2 through K27- and K29-linkage chains

[90][125]. This was accompanied by LRRK2 aggregation and neuronal protection in primary neurons and LRRK2-G2019S transgenic Drosophila flies. Analysis of postmortem brains of PD patients revealed colocalization of WSB1 and LRRK2 in the Lewy bodies. Moreover, almost all Lewy bodies (97%), identified by alpha-synuclein staining, had WSB1 reactivity, and about 25% of Lewy bodies contained LRRK2

[90][125]. This was specific for PD but not for Alzheimer’s disease, as WSB1 reactivity was not detected in plaques

[90][125].

Functional inhibition of the LRRK2 GTPase domain and kinase activity by GTP-binding inhibitors (compounds 68- or Fx2149) increased G2019S-LRRK2 polyubiquitination at K27- and K63-linkages in HEK293T cells cotransfected with LRRK2 constructs and various HA-tagged ubiquitin constructs

[91][126]. Both compounds increased G2019S-LRRK2-linked ubiquitinated aggregates, thus underlying a critical role of the GTP-binding for LRRK2-linked ubiquitination and formation of aggregates

[91][126]. Treatment of C57BL/6J mice with Fx2149 (10 mg/kg intraperitoneally twice daily for three days) significantly increased endogenous ubiquitination of brain LRRK2

[91][126].

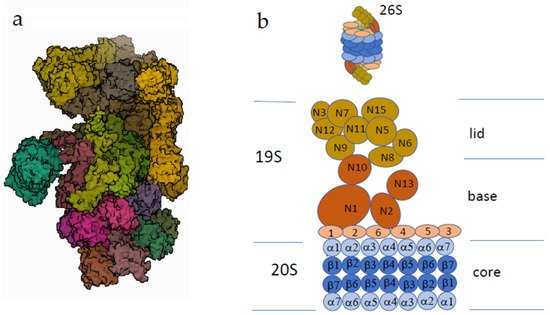

5. Concerted Mechanisms of Different Types of Ubiquitination and Deubiquitination in Mitophagy (Monoubiquitination and K6-, K11-, K27-, and K63-Linked Polyubiquitination)

Studies of postmortem brain samples of PD patients and experimental PD models provided convincing evidence for the critical role of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in the neuronal loss in PD

[92][93][94][95][96][97][145,146,147,148,149,150]. Elimination of damaged mitochondria (mitophagy) is of vital importance for both neighboring mitochondria and the whole cell

[98][99][151,152]. The proteins related to PD, PINK1 (serine/threonine protein kinase) and parkin (E3 ubiquitin ligase), are the major players in mitophagy regulation.

Under normal conditions (with the high value of mitochondrial membrane potential), PINK1 is translocated to the mitochondrial inner membrane via TOM (translocase of outer membrane) and TIM (translocase of inner membrane) complexes

[100][155] and degraded after a series of proteolytic cleavages. This process represses mitophagy. Mitochondrial depolarization induced by mitochondrial poisons (MPTP, the insecticide rotenone, or the herbicide paraquat) blocks PINK1 import and triggers its accumulation on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM)

[101][156]. Being accumulated on the OMM, PINK phosphorylates both parkin (S65 of the N-terminal ubiquitin-like domain)

[102][157] and ubiquitin moieties of ubiquitin conjugates attached to certain ubiquitin-modified OMM proteins

[103][104][158,159]. This phosphorylation activates parkin and stimulates its recruitment from the cytosol to mitochondria via direct binding of phosphoubiquitin conjugates on the mitochondrial surface. Active parkin promotes polyubiquitination of various mitochondrial substrates; this causes phosphorylation of their ubiquitin conjugates by PINK1, further parkin recruitment, activation, and ubiquitination of protein substrates by a feed-forward mechanism

[98][105][132,151].

The combination of techniques (cells expressing GFP-parkin, use of uncouplers causing mitochondrial depolarization, antibodies specific for polyubiquitin species, Western blot analysis, and mass spectrometry) has led to the identification of the protein substrates ubiquitinated by parkin and the type of ubiquitination

[105][106][107][108][109][110][111][127,128,129,130,131,132,133]. In the context of an extraordinarily large number of parkin substrates, recognized in proteomic studies, parkin is considered as a promiscuous E3 ligase; its flexible specificity is based more on the presence of phosphoubiquitin on the surface of substrates rather than on the identity of the substrates per se

[105][132]. Moreover, parkin is even considered as “the first phospho-ubiquitin-dependent E3”

[105][132].

68. Deubiquitinases (USP8, USP15, USP30, USP33, USP35, UCH-L1) Removing Atypical Ubiquitin Conjugates from PD-Related Proteins

Deubiquitinases (DUBs) are known to be another factor of mitophagy regulation

[112][113][114][115][172,173,174,175]. There are more than 90 different human DUBs

[116][176]. These include several enzymes cleaving peptide bonds of atypical ubiquitin chains and thus regulating mitophagy

[98][105][117][132,151,177]. Some of these enzymes deubiquitinate parkin itself, while the others act on the ubiquitinated protein substrates of parkin. USP8 regulates parkin autoubiquitination during mitophagy

[109][130]. The USP8 silencing impaired mitophagy: the U2OS-GFP-parkin cells transfected with USP8 siRNA did not demonstrate a loss of mitochondrial staining of parkin substrates. USP8 deubiquitinated parkin itself by selectively removing K6-linked ubiquitin conjugates from it

[109][130]. Interestingly, in contrast to mitophagy promotion, USP8 seems to play an opposite role in the context of autophagy: USP8 interacts with alpha-synuclein and cleaves its K63 ubiquitin conjugates, preventing alpha-synuclein degradation in lysosomes

[118][89]. Thus, USP8 represents a rare example as a DUB that regulates mitophagy positively, whereas most of the known deubiquitinases (USP33, USP15, USP35, USP30) regulate it negatively

[119][120][121][122][178,179,180,181].

Another DUB, USP33, deubiquitinated parkin mainly at Lys435, removing not only K48, but also atypical K6-, K11-, and K63-linked ubiquitin conjugates. Moreover, USP33 silencing protected human neuroblastoma cells from MPTP-induced apoptotic death

[119][178]. USP15 was identified as a DUB counteracting parkin-mediated ubiquitination of mitochondrial proteins

[120][179]. Overexpression of this enzyme antagonized the clustering of both K48- and K63-linked ubiquitin chains on depolarized mitochondria. Knockdown of USP15 prevented mitophagy of PD patient fibroblasts with mutations in the parkin-encoding gene and decreased parkin levels

[120][179].

Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1) is genetically associated with PD

[123][182]. UCH-L1, downregulated in PD patients

[124][183] and found in Lewy bodies of autopsy brains

[125][184], is also involved in the deubiquitination of atypical ubiquitin chains.

79. M1-Linked Ubiquitination

The linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC), composed of heme-oxidized IRP2 ligase-1 (HOIL-1L) acting as an E3 ligase, associated with HOIP (HOIL-1L-interacting protein) and SHANK-associated RH domain interacting protein (SHARPIN), generates a novel type of Met1 (M1)-linked linear polyubiquitin chain

[126][144]. Certain evidence exists that LUBAC is the only E3, linking linear polyubiquitin chains by peptide bonds between the C-terminal G76 of ubiquitin and the α-NH2 group of M1 of another ubiquitin

[126][144].

There is evidence that LUBAC assembles M1-linked ubiquitin preferentially on pre-existing K63-linked ubiquitin and some other linkages

[127][128][189,190]. LUBAC may be (perhaps indirectly) implicated in PD. At least, it was found that parkin activated LUBAC-mediated linear ubiquitination of essential modulator (NEMO) by modifying this modulator with K63-linked ubiquitin

[129][142]. Other scenarios include LUBAC-mediated M1 linear ubiquitination of multiple components of the NF-κB signaling pathway and mitogen-activated protein kinases (NEMO, etc.)

[130][131][141,143].