You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Federica Cherchi and Version 3 by Vicky Zhou.

Ligands of the Gi protein-coupled adenosine A3 receptor (A3R) are receiving increasing interest as attractive therapeutic tools for the treatment of a number of pathological conditions of the central and peripheral nervous systems (CNS and PNS, respectively). Their safe pharmacological profiles emerging from clinical trials on different pathologies (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and fatty liver diseases) confer a realistic translational potential to these compounds, thus encouraging the investigation of highly selective agonists and antagonists of A3R.

- adenosine receptors

- Adenosine A3 ligands

- chronic pain

- brain ischemia

1. Introduction: Adenosine and Its Receptors

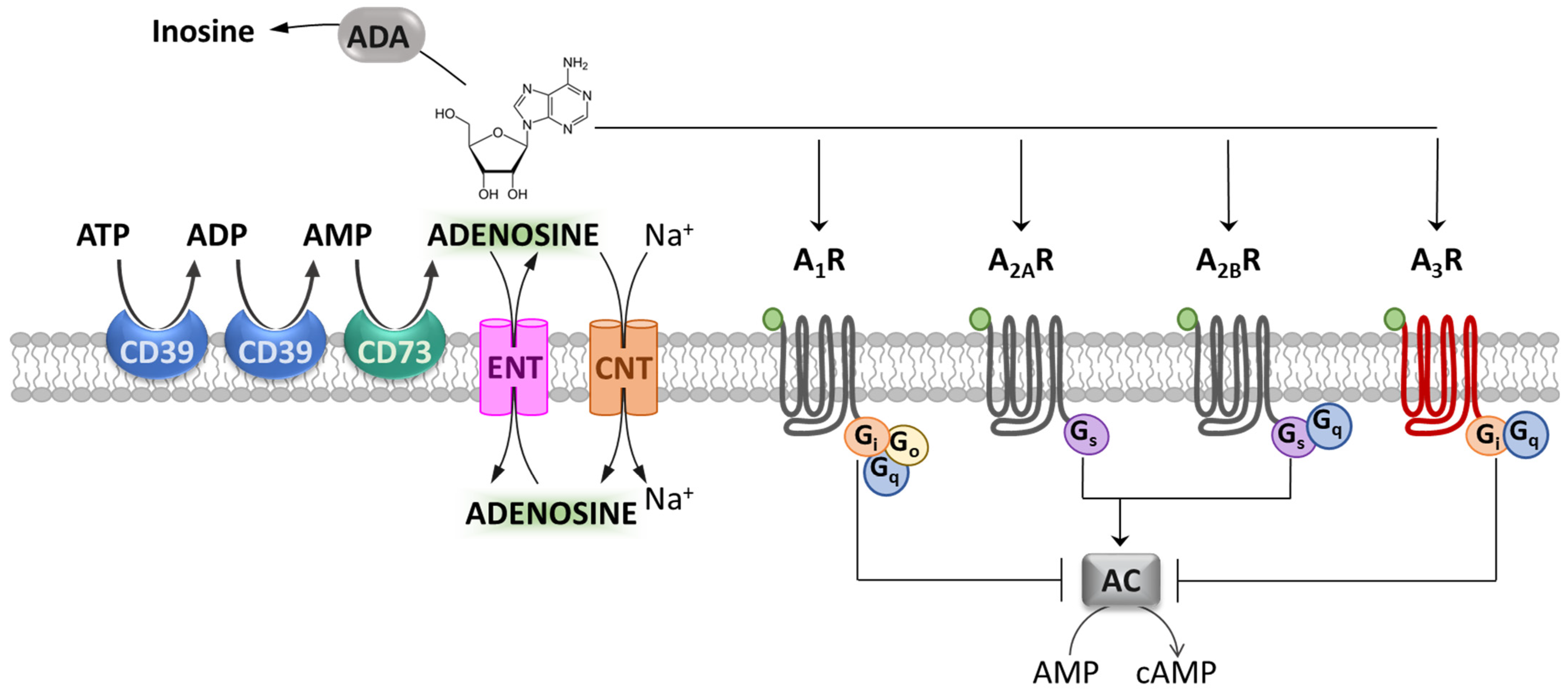

Adenosine is a ubiquitous endogenous neuromodulator and is recognized as one of the most evolutionarily ancient and pervasive signaling molecules [1]. In particular, adenosine plays a crucial role in neuron-to-glia communication in both the central and peripheral nervous systems (CNS and PNS, respectively) [2][3][4][2,3,4] as well as in inflammatory processes throughout the periphery [5]. The effects of adenosine are mediated by the activation of four G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR): A1, A2A, A2B and A3 receptors (A1Rs, A2ARs, A2BRs and A3Rs). A1Rs, A2ARs and A2BRs are fairly conserved throughout evolution, showing 80–95% homology among species, whereas A3Rs present high inter-species variability [6], with only 74% sequence homology between rat and human [7]. In general, A1Rs and A3Rs are coupled to adenylyl cyclase (AC) inhibition through G proteins of the Gi and Go family [8][9][8,9] (Figure 1), whereas A2AR and A2BR actions rely on the stimulation of adenylyl cyclase by Gs or Golf. However, beyond these canonical signaling mechanisms, the stimulation of A1Rs and A3Rs can also elicit Gq-mediated release of calcium ions from intracellular stores [10]. On the other hand, in addition to Gs, A2BR receptors can activate phospholipase C, which also occurs through Gq [10] (Figure 1). Moreover, all adenosine receptors are coupled to mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, which include extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 (ERK1), ERK2, JUN N-terminal kinase and p38 MAPK [10].

Figure 1. Adenosine and its receptors. Schematic representation of adenosine metabolism, transport and metabotropic receptors. The ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73 metabolize ATP and ADP to AMP, and AMP to adenosine. The equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT) or concentrative nucleoside transporter (CNT) families mediate adenosine reuptake. Adenosine metabotropic receptors (A1, A2A, A2B and A3 receptors: A1R, A2AR, A2BR and A3R) are differently coupled to adenylyl cyclase (AC) inhibition or stimulation. Adenosine deaminase (ADA) deactivates extracellular adenosine by converting it into inosine.

1.1. Adenosine Receptors in Peripheral Tissues

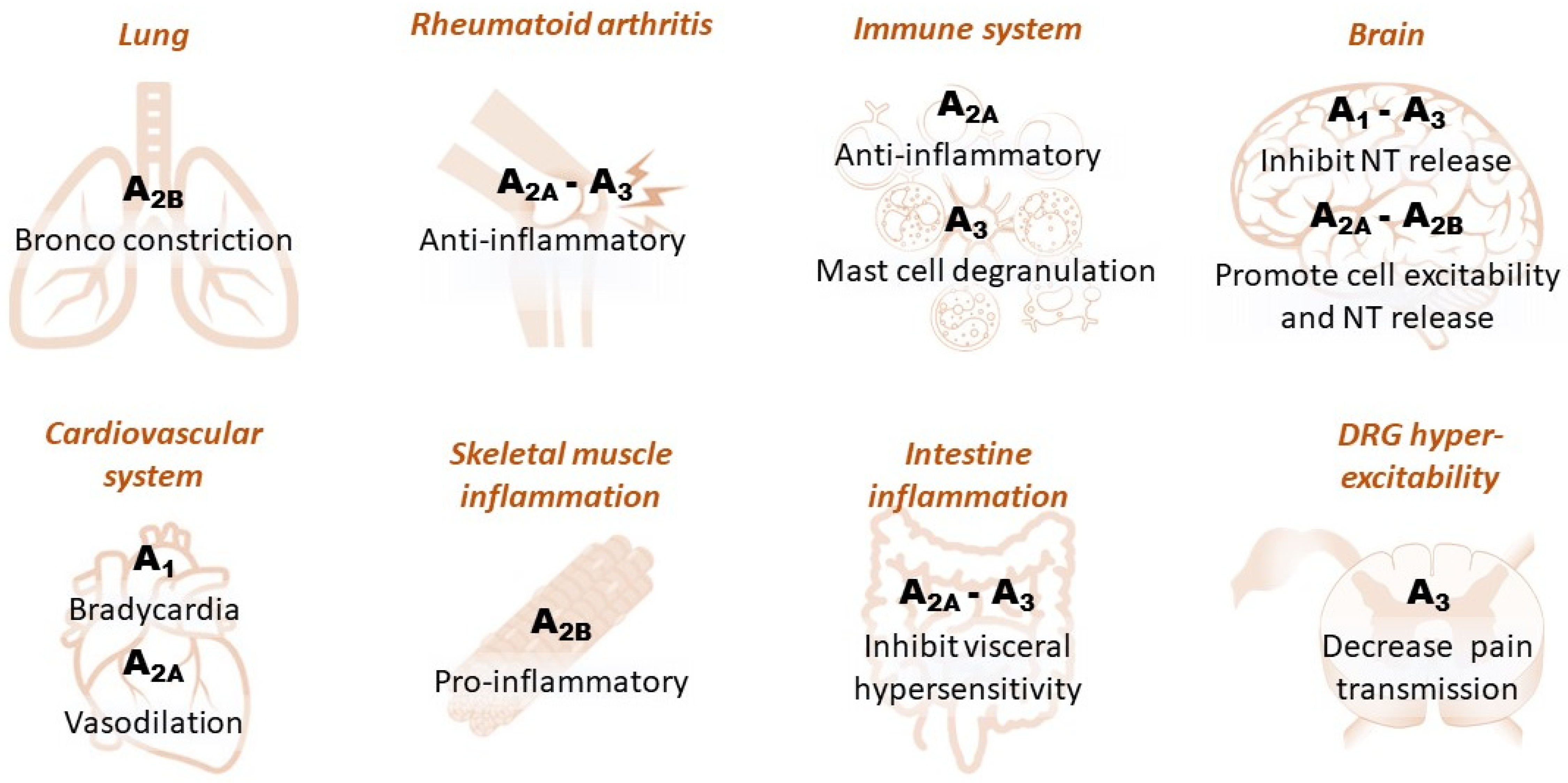

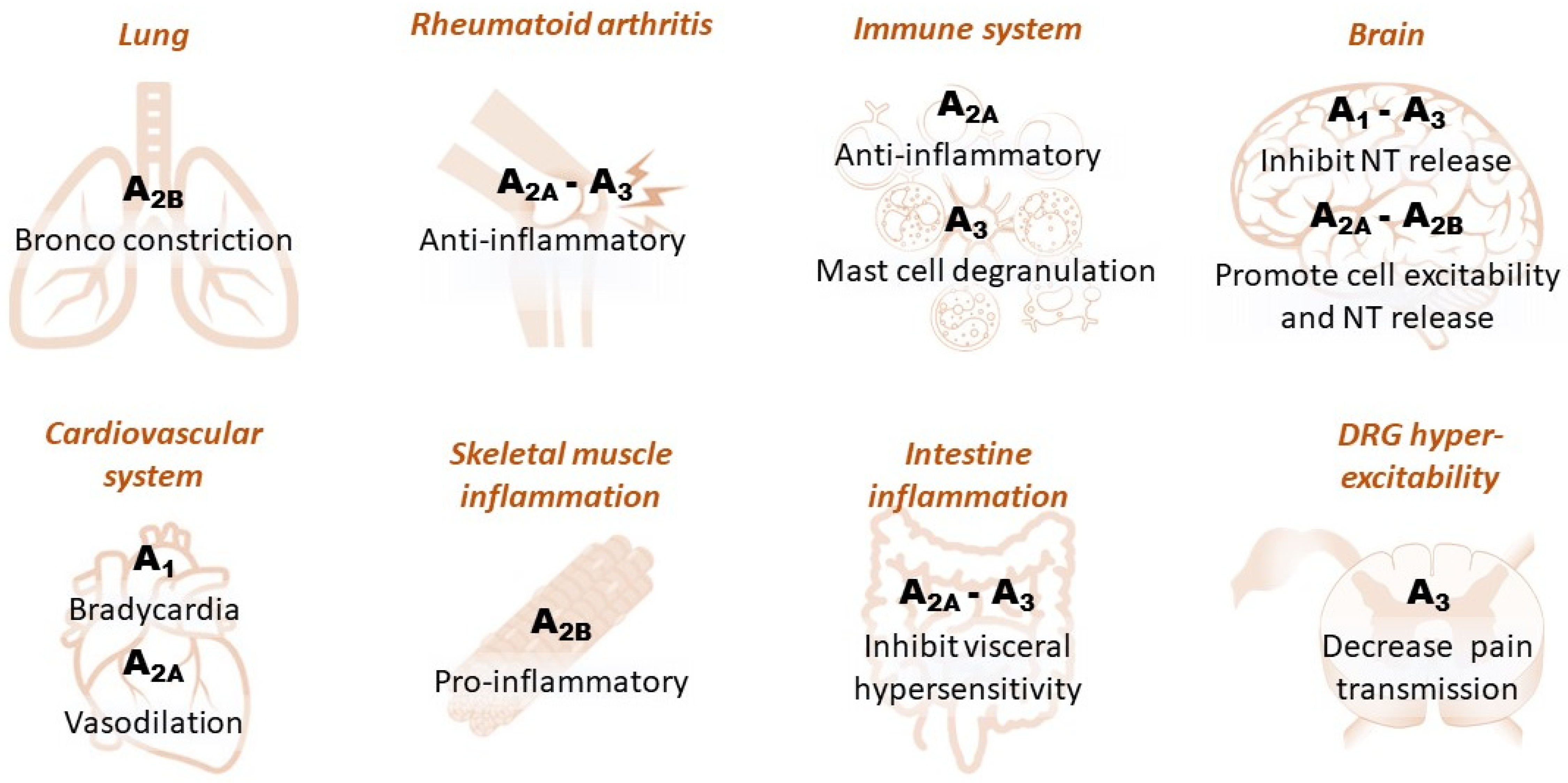

In the periphery, adenosine receptors modulate a number of events, including inflammation, metabolism and cell-to-cell signaling. A pervasive action of peripheral adenosine is on A1Rs in the heart (Figure 2), where they are highly expressed and mediate potent bradycardia. For this reason, adenosine is administered as an emergency drug in arrhythmic conditions, e.g., paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia [19].

Figure 2. Schematic diagram illustrating the effect of different adenosine receptor subtypes in peripheral and central tissues. Dorsal root ganglia: DRG.

1.2. Adenosine Receptors in the CNS

At the central level, A1Rs are the primary effectors of adenosine actions in the CNS, where they are widely distributed, with the highest levels reported in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus [20][29]. A1Rs are known to inhibit neurotransmitter release by inhibiting presynaptic voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) [21][22][32,33] and to decrease neuronal excitability by increasing postsynaptic potassium conductance [23][34]. During brain ischemia, these actions provide important adenosine-mediated neuroprotection by maintaining cells in a low energy consumption state and by counteracting excessive glutamate release, which is responsible for the excitotoxic damage [24][35]. The functional effect of the Gs-coupled A2AR subtype in the CNS is the opposite to that of A1Rs, as these receptors are reported to enhance glutamate release by facilitating calcium entry through presynaptic VGCCs and inhibiting its uptake [25][36]. Moreover, A2AR inhibits voltage-dependent potassium channels, thus promoting cell excitability and neurotransmitter release [26][37] and exacerbating excitotoxic damage during ischemic/hypoxic conditions [26][37]. The expression levels of A2AR in the CNS are comparable to those of A1Rs only in the caudate/putamen nuclei, where they play a deleterious role in the acute phases of an ischemic insult by increasing brain damage and neurological deficit [27][38] after middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo) in rats [16].2. Therapeutic Potential of A3R Ligands

2.1. A3R Ligands as Therapeutic Tools in Brain Ischemia

There are no current treatments for stroke that are able to prevent or alleviate neuronal loss and tissue damage in the acute or post-ischemic phases after the insult. The only therapy strategies currently in use are the administration of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) within the first 3–4 h after the insult [28][52] and, in some cases, hypothermia [29][30][53,54]. As stated above, adenosine is released in great amounts during hypoxic/ischemic conditions and plays a pervasive role in this pathology by activating all subtypes of P1 receptors. Both protective and deleterious effects have been described upon their selective activation, depending on the receptor subtype and timing after the insult.

The most widely recognized effect of adenosine during brain ischemia is the neuroprotective role exerted by the Gi-coupled A1R subtype, which is known to inhibit exaggerated glutamate release during excitotoxic damage in the ischemic core and penumbra [22][23][33,34]. As a result of the wide distribution of A1Rs within the brain, they have a higher impact compared to A2AR, A2BR and A3R subtypes [18]. Unfortunately, due to unacceptable side effects at the peripheral level (bradycardia and hypotension), A1R-selective agonists are not suitable for clinical use in preventing post-ischemic damage [23][34].

Hence, research was driven towards the other Gi-coupled adenosine receptor subtype, A3R. Interestingly, A3R has been proposed as a novel therapeutic target for a number of pathologies [31][32][42,43], and A3R-selective nucleosides are already in phase 2 and/or 3 clinical trials for autoimmune inflammatory diseases, liver cancer and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (see www.clinicaltrials.gov; NCT00556894; NCT02927314; 12 March 2022) [33][34][49,50]. Notably, activation of A3R in humans by the selective and orally bioavailable A3R agonist IB-MECA (1-deoxy-1-[6-[[(3-iodophenyl)methyl]amino]-9H-purine-9-yl]-N-methyl-β-D-ribofuranuronamide) and its chlorinated counterpart Cl-IB-MECA (2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine-5-N-methyluronamide) is not associated with cardiac or hemodynamic effects [34][50], and they have shown encouragingly safe profiles [33][49]. Further attention was focused on this adenosine receptor subtype for the investigation of innovative pain-relieving strategies, as detailed below, due to evidence for their good “safety and security” profile.

Figure 3. Adenosine A3 receptors and pain control. A3 receptors (A3Rs) are expressed on rat DRG neurons, and their activation by the selective agonist MRS5980 decreases action potential (AP) neuronal firing and inhibits N-type voltage-gated calcium channels [46][110]. A3Rs expressed on CD4+ T cells, but not on mouse DRG neurons, promote interleukin-10 (IL-10) release that, by activating IL-10 receptors (IL-10R) on DRG neurons, reduces neuronal excitability by inhibiting AP firing [45][117].

Figure 3. Adenosine A3 receptors and pain control. A3 receptors (A3Rs) are expressed on rat DRG neurons, and their activation by the selective agonist MRS5980 decreases action potential (AP) neuronal firing and inhibits N-type voltage-gated calcium channels [46][110]. A3Rs expressed on CD4+ T cells, but not on mouse DRG neurons, promote interleukin-10 (IL-10) release that, by activating IL-10 receptors (IL-10R) on DRG neurons, reduces neuronal excitability by inhibiting AP firing [45][117].

2.2. A3R Ligands as Therapeutic Tools in Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is a highly debilitating condition, disturbing all aspects of people'sur daily experience, from social life to career-related contexts. The pharmacological tools available to date are sometimes inadequate or, as in the case of opioids, limited by serious adverse effects [35][80]. In an effort to find innovative, non-opioid pain-relieving compounds, many experimental reports have identified adenosine receptors as potential targets for acute or chronic pain management. The first proof of adenosine’s anti-nociceptive effect dates from the 1970s, when administration of adenosinergic agonists proved effective in pain control. These studies emphasized the role of adenosine A1Rs in producing anti-nociceptive effects, with some effects ascribed to the A2AR subtype [36][37][81,82]. Adenosine involvement in peripheral nociception was further confirmed; e.g., the local administration of exogenous A1R agonists to the hind paw of the rat produces anti-nociceptive effects in a pressure hyperalgesia model [38][83], whereas local administration of A2R agonists enhances pain responses [39][84], an action due to adenosine A2AR activation, as confirmed by using the selective agonist CGS21680 [40][85]. Later, it was demonstrated that the anti-nociceptive action of A1R agonists could be ascribed to AC inhibition and to the consequent decrease in cAMP production in sensory nerve terminals [41][42][86,87]; thus, a robust protective role of A1R agonists emerged [43][88]. On the other hand, the A2AR-mediated promotion of cutaneous pain resulted from the stimulation of AC, leading to increased cAMP levels in sensory nerve terminals [41][42][86,87], thus producing opposite effects to those elicited by the anti-hyperalgesic, Gi-coupled A1R subtype. However, the relation between A2ARs and pain has been controversial, with evidence supporting either pro-nociceptive or anti-nociceptive activity depending on the receptor localization and animal models of pain [43][88]. Indeed, a relevant A2AR-mediated anti-nociceptive effect was described in a recent study demonstrating that central neuropathic pain evoked by dorsal root avulsion could be reversed by a single intrathecal injection of A2AR agonists [44][89]. Importantly, the effect of MRS5980 on neuronal firing was also abolished by pre-treatment with an anti-IL-10-selective antibody, thus unequivocally pointing to this anti-inflammatory cytokine as the main effector produced by CD4+ T cells upon A3R activation to inhibit neuronal excitability (Figure 3) [45][117]. Figure 3. Adenosine A3 receptors and pain control. A3 receptors (A3Rs) are expressed on rat DRG neurons, and their activation by the selective agonist MRS5980 decreases action potential (AP) neuronal firing and inhibits N-type voltage-gated calcium channels [46][110]. A3Rs expressed on CD4+ T cells, but not on mouse DRG neurons, promote interleukin-10 (IL-10) release that, by activating IL-10 receptors (IL-10R) on DRG neurons, reduces neuronal excitability by inhibiting AP firing [45][117].

Figure 3. Adenosine A3 receptors and pain control. A3 receptors (A3Rs) are expressed on rat DRG neurons, and their activation by the selective agonist MRS5980 decreases action potential (AP) neuronal firing and inhibits N-type voltage-gated calcium channels [46][110]. A3Rs expressed on CD4+ T cells, but not on mouse DRG neurons, promote interleukin-10 (IL-10) release that, by activating IL-10 receptors (IL-10R) on DRG neurons, reduces neuronal excitability by inhibiting AP firing [45][117].3. Conclusions

In summary, it can be concluded that A3Rs are emerging as promising targets for the treatment of a number of pathologies due to the limited side effects of their ligands in comparison to those targeting other adenosine receptor subtypes (i.e., A1Rs or A2ARs). In particular, A3R antagonists proved effective in preclinical animal models of brain ischemia and OGD in hippocampal slices, thus paving the way for the development of new, highly selective A3R blockers for the treatment of stroke. Furthermore, valuable evidence from rodent models of chronic pain indicates the possible use of selective A3R agonists as non-narcotic anti-hyperalgesic agents for pain control.