4. Evidence for Lipids Action as Second Messengers

Many mammalian TRP channels can be characterized as ionotropic receptors since they can be activated directly under physiological conditions by physical stimuli such as heat, cold, mechanical, or by natural chemicals such as capsaicin, menthol, or mustard oil

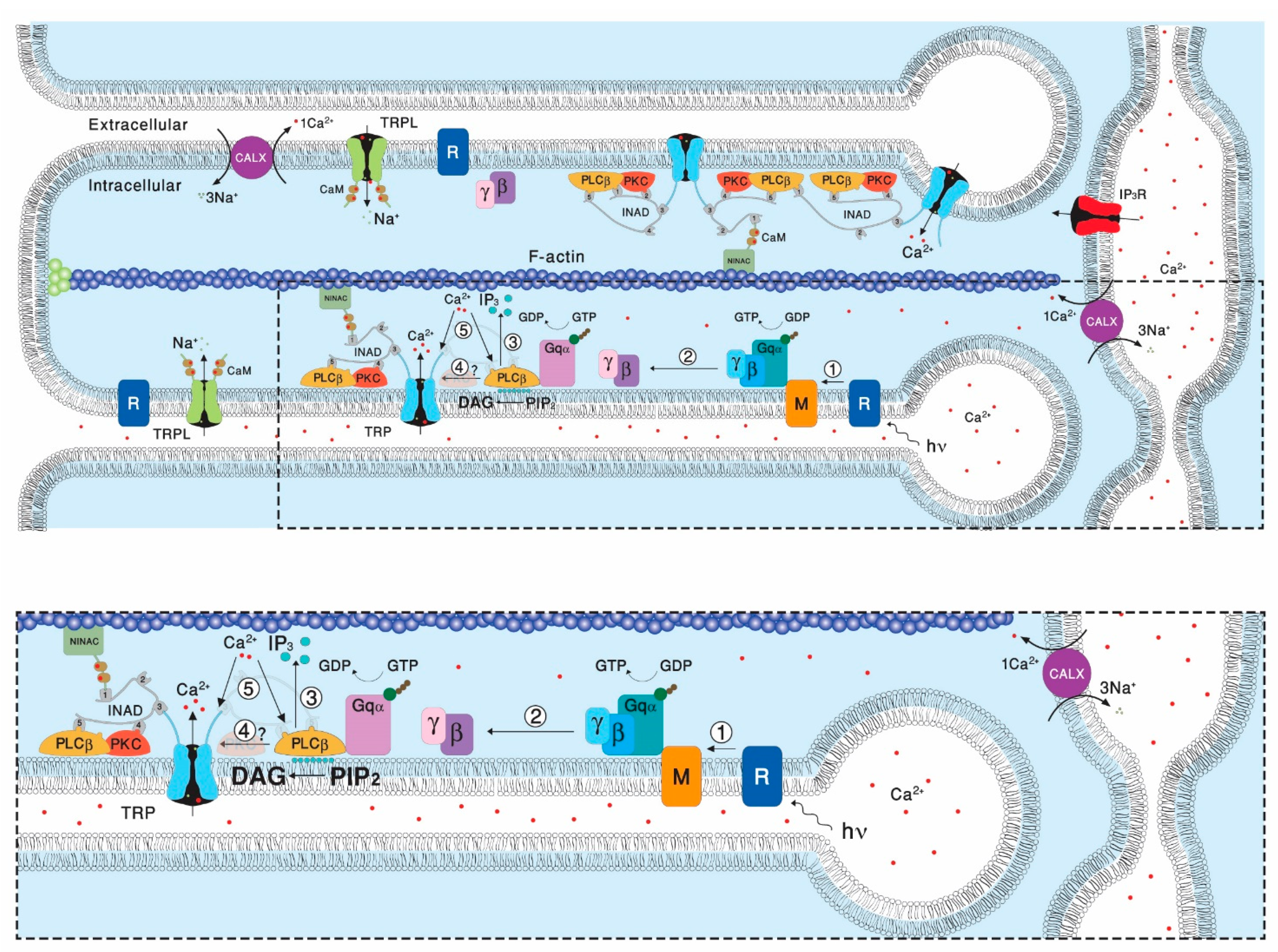

[19][50]. One of the key features of presumably all members of the TRPC subfamily is their indirect physiological activation via PLCβ-mediated signal transduction cascades. Since PLC activity is essential for activation of the TRP/TRPL channels, recycling its substrate, PIP

2, is essential for proper light response. PLC catalyzes hydrolysis of the membrane phospholipid PIP

2 into water soluble IP

3 and membrane-bound diacylglycerol (DAG,

[20][51]). This enzymatic reaction is enhanced by illumination and initiates a cyclic enzymatic pathway called the PI cycle. Many enzymatic components of the complex PI cycle were discovered using genetic dissection by screening for mutations and utilizing the power of the

Drosophila molecular genetics

[21][52]. Following PLC activation, the phospholipid branch of the PI cycle begins by DAG transport through endocytosis to the endoplasmic reticulum designated submicrovillar cisternae (SMC). Subsequently, DAG is inactivated by phosphorylation and converted into phosphatidic acid (PA,

[22][23][53,54] via DAG kinase (DGK), encoded by the retinal degeneration A (

rdgA) gene that was discovered as a mutant causing rapid retinal degeneration in the dark

[22][23][53,54].

5. PUFAs Activation of TRP and TRPL Channels in the Dark

One of the striking findings of Hardie and colleagues in studies of

Drosophila photoreceptors was the demonstration that PUFAs such as linolenic or linoleic acid (LA) are potent activators of the TRP/TRPL channels in the dark. This robust, but still slower activation relative to light activation was demonstrated in both photoreceptor cells

[24][25][77,78] and in cultured S2 cells (

[24][25][77,78]) and HEK cells

[26][73] heterologously expressing TRPL channels.

A question arises as to whether PUFA activation of the channels in the photoreceptor cells reflects the physiological mechanism of channel activation. Supporting evidence was provided by isolation of the Inactivation No Afterpotential E (

inaE) mutant by Pak and colleagues

[27][91]. The

inaE gene was identified as encoding a homologue of the mammalian

sn-1 type DAG lipase, which, rather than PUFAs, releases mono-acyl glycerol (MAGs) and, are at best, weak and slowly acting channel agonists when applied exogenously (Hardie, unpublished results, see

[28][49]). Furthermore, the

inaE gene product immunolocalizes to the cell body with occasional puncta in the rhabdomere

[27][91]. Mutant flies, expressing low levels of the

inaE gene product, have an abnormal light response, while the activation of the light sensitive channels was not prevented

[27][91]. The discovery of the

InaE gene was an important step in the endeavor to elucidate lipids regulation of the channels

[21](see reviews by and [52]). However, for PUFA generation, either an sn-2 DAG lipase or an additional enzyme (MAG lipase) would be required, but there is no evidence of either in

Drosophila photoreceptors and there is also no evidence that PUFAs are even generated in response to illumination

[29][74].

6. Photomechanical Gating of the TRP/TRPL Channels

Many studies have shown that membrane-protein function is regulated by the composition of the lipid bilayer in which the proteins are embedded. The commonality of the changes in protein function by changes in their lipid environment suggests an underlying physical mechanism, and at least some of the changes are caused by altered bilayer physical properties

[30][92]. Although TRP/TRPL channel activation by PUFA is most likely not a physiological mechanism, it provides an important insight into mechanisms by which membrane lipid modulation by a variety of PUFAs causes dramatic effects on TRP/TRPL channel gating and its properties. Accordingly, it was previously showed that removal of open channel block (OCB) from TRP/TRPL channels by PUFA resulted from an increased flow rate of the blocking divalent cations through the channel pore

[25][78]. Modulation of the interface of the channel and its surrounding membrane lipids might underlie the increase in the flow rate of the blocking cations and the removal of the OCB. Various methods were applied to modify membrane lipid properties around the TRPL channel, including: stretch of the plasma membrane by hypoosmotic solutions, sequestration of PIP

2 by polylysine, and application of various lipids. Alternatively,

we blocked PUFA action

was blocked bby the GsMTx-4 tarantula toxin, a specific inhibitor of mechanosensitive channels, which acts on the channel-membrane lipid interface

[31][32][93,94]. These results thus suggested that lipids do not affect the TRPL channel as second messengers but rather as modifiers of membrane lipid-channel interactions

[25][78].

7. Lipid Rafts and Modulation of TRPL Channel Activity by Cholesterol

Lipid rafts are membrane microdomains rich with sterols, sphingolipids, and specific proteins. Lipid rafts have been found in all types of cells. It has been generally agreed that lipid rafts generate signaling platforms by assembling in close proximity to different signaling molecules for the optimal function of signal transduction cascades

[33][96]. Many signaling proteins including ion channels have been found to localize in lipid rafts, while the association with rafts was required for the regulation of some integral membrane protein activities

[34][35][97,98]. The actions of lipid rafts are often associated with the effect of cholesterol on membrane structure or directly on membrane proteins. Channels have been found in detergent-resistant membrane (DRM) fractions, indicating the inclusion of channels in lipid rafts

[36][99].

8. Conclusions

Despite many efforts over the years, the gating mechanism of the

Drosophila TRP/TRPL channels still poses a long-standing enigma. The findings that mammalian TRPC channels can be activated by exogeneous application of DAG together with the solved atomic structures of mammalian TRPC channels by cryo-EM constitute major progress towards understanding TRPC channel gating. Nevertheless,

Drosophila retina is a highly valued preparation for investigating the roles of TRP/TRPL channels under physiological conditions. This is due to their high expression levels and their known functional role as the light-activated channels. There remains no comparable preparation for the mammalian TRPC channels that contains a TRP-enriched tissue combined with the power of the

Drosophila molecular genetics and the accuracy of light activation. Moreover, studies of

Drosophila phototransduction revealed that under physiological conditions,

Drosophila TRP operates as an essential part of a multimolecular signaling complex. There are indications that mammalian TRPC channels also operate in a similar manner, but it is difficult to study these mechanisms in the native mammalian systems because of the scarcity of these signaling proteins in the native systems.

Crucial unsolved questions in

Drosophila photoreceptor physiology are related to the mechanism by which DAG accumulation following DGK inhibition activates the channels. In particular, why exogeneous application of DAG to an excised signaling membrane activates the channels in orders of magnitude slower than light activation in the intact photoreceptor cell. The use of photoactivated DAG analogues

[37][125] may help in solving this question.

An available

Drosophila mutant in which the TRP channels are constitutively active (i.e., the

trpP365 mutant) is a highly valuable tool for investigating TRP gating in the future, which can be used together with the solved atomic structure of mammalian TRPCs. In addition, even if PUFA is not the native second messenger of excitation, its robust effect of opening the TRP/TRPL channels in the dark in vivo and TRPL in tissue culture cells can be studied in detail and provide useful information on channel gating.

Finally, the photomechanical gating mechanism of TRP/TRPL channels that was put forward by Hardie and colleagues needs to be revisited. According to this model and the supporting evidence, light-induced PIP

2 hydrolysis by PLC converts a phospholipid with a large hydrophilic head group (PIP

2) into DAG with a minute hydrophilic head group. This enzymatic reaction leads to a generation of a measurable force that may open the channels mechanically.