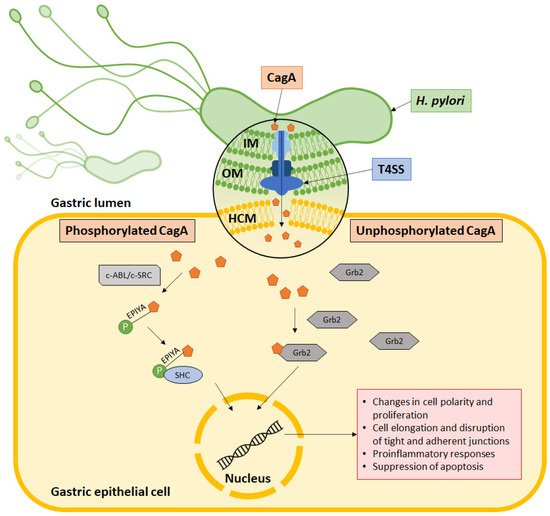

Helicobacter pylori is well established as a causative agent for gastritis, peptic ulcer, and gastric cancer. Armed with various inimitable virulence factors, this Gram-negative bacterium is one of few microorganisms that is capable of circumventing the harsh environment of the stomach. The unique spiral structure, flagella, and outer membrane proteins accelerate H. pylori movement within the viscous gastric mucosal layers while facilitating its attachment to the epithelial cells. Furthermore, secretion of urease from H. pylori eases the acidic pH within the stomach, thus creating a niche for bacteria survival and replication. Upon gaining a foothold in the gastric epithelial lining, bacterial protein CagA is injected into host cells through a type IV secretion system (T4SS), which together with VacA, damage the gastric epithelial cells.

- Helicobacter pylori

- flagella

- outer membrane protein

- CagA

- VacA

- type IV secretion system

- pathogenesis

1. H. pylori Structures Facilitate Bacterial Motility in the Thick Mucosal Layers

2. OMPs Facilitate Bacterial Attachment to the Gastric Epithelial Cells

3. H. pylori Urease Neutralizes Acidic pH

4. H. pylori Evades Host Immune Response

5. Type IV Secretion System Penetrates Gastric Epithelial Cells

6. CagA Perturbs Normal Cell Activities