Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Wiebke Rubel and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Anaplasma ovis, tick-borne pathogens with zoonotic potential, have been detected in small ruminants in Europe and North America in the past. However, knowledge about the distribution of these pathogens in the German small ruminant population is scarce. These intracellular bacteria cause tick borne fever and ovine anaplasmosis, respectively.

- Anaplasma phagocytophilum

- Anaplasma ovis

- tick-borne fever

- ovine anaplasmosis

- sheep

- goat

- Germany

1. Introduction

Across Europe and North America, sheep and goats can become infected with obligate intracellular bacteria of the genus Anaplasma. Whereas Anaplasma phagocytophilum is widespread in many European countries, an infection with Anaplasma ovis mainly occurs in the Mediterranean Basin [1]. However, reports about the focal occurrence of A. ovis in Central European countries like Hungary, Slovakia and Germany are increasing [2][3][4][2,3,4]. Both pathogens are also present in the US sheep population, but detailed information about the dissemination is lacking [5][6][5,6].

Wild ruminants may act as a reservoir for both pathogens in Europe and North America [3][7][8][9][10][11][3,7,8,9,10,11]. The transmission of Anaplasma spp. usually happens through tick bites [1]. The main vectors of A. phagocytophilum are Ixodes ricinus in Europe, as well as Ixodes scapularis, Ixodes pacificus and Ixodes spinipalpis in North America [1][11][12][13][1,11,12,13]. Different tick species belonging to the genera Dermacentor, Rhipicephalus and Hyalomma are considered to transmit A. ovis [13][14][13,14]. In recent years, A. ovis was also found in sheep keds (Melophagus ovinus) but their vector competence remains doubtful [15][16][15,16].

The replication of A. phagocytophilum takes place within the vacuoles of neutrophil granulocytes and sometimes also lymphocytes [17]. This causes granulocytic anaplasmosis in many domestic animals, such as horses [18][19][18,19], cattle [20][21][20,21], dogs [22][23][22,23] and cats [24][25][24,25], and also in humans [12]. In small ruminants, A. phagocytophilum results in tick-borne fever (TBF) and affected animals suffer from high fever, anorexia and dullness [26][27][28][26,27,28]. Neutropenia and thrombocytopenia are the haematological key findings in affected sheep and goats [26][29][26,29]. Immunosuppression causes a high susceptibility to secondary infections like Mannheima haemolytica and Bibersteina trehalosi and leads to respiratory distress in lambs [30][31][30,31]. Furthermore, A. phagocytophilum favours co-infections with staphylococcal bacteria which cause tick-pyaemia with polyarthritis [29]. TBF and co-infections can be fatal for lambs [29][30][31][29,30,31]. However, mild courses of A. phagocytophilum were reported but affected lambs had reduced growth rates [28]. Goats show similar clinical signs to sheep after an infection with A. phagocytophilum, but to a lesser extent [26][32][33][26,32,33].

Anaplasma ovis mainly affects the ovine and caprine erythrocytes [34] but can also be found in wild ungulates like roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) and red deer (Cervus elaphus) [7][15][35][7,15,35]. Humans rarely become infected [36]. The pathogen causes ovine anaplasmosis especially in sheep in poor health [37]. Main clinical signs in sheep are fever, severe anaemia, extreme weakness, anorexia, and weight loss [34][37][38][39][34,37,38,39]. Moreover, haemoglobinuria and icteric carcasses were also described in sheep infected with A. ovis [2][39][2,39]. An acute infection results in decreased values of red blood cells, haemoglobin and packed cell volume [40]. Although the same signs are described for goats as for sheep, A. ovis appears to be more pathogenic for goats [41].

In Germany, A. phagocytophilum was identified in I. ricinius across the country with detection rates between 1.9% and 5.4% [42][43][44][42,43,44]. Although A. phagocytophilum has been well described in domestic animals [19][20][25][45][19,20,25,45] and wild ungulates [9][46][9,46], knowledge of the occurrence of the pathogen in German sheep and goat flocks is still limited. A molecular investigation revealed an infection rate of 4% (n = 255) in sheep from Northern Germany [8] and a clinical case of TBF was described in a goat from western Germany [47]. Recently, A. phagocytophilum was detected by PCR in five sheep flocks located in the southern part of the country [4]. In the same study, A. ovis was identified for the first time in a German sheep flock.

2. Animals

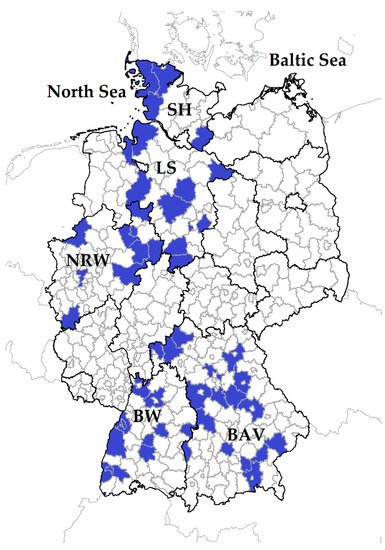

Serum samples from sheep and goats were available from a Q fever study conducted from winter 2017 to spring 2018, and details were described elsewhere [48][49]. In brief, the specimens were collected from 3178 small ruminants (2731 sheep, 447 goats) within 71 flocks located in five federal states: Schleswig-Holstein (SH), Lower Saxony (LS), North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), Baden-Wuerttemberg (BW) and Bavaria (BAV) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. In total, 71 small ruminant flocks were sampled in five German federal states: Schleswig-Holstein: SH; Lower Saxony: LS, North Rhine-Westphalia: NRW, Baden-Wuerttemberg: BW, Bavaria: BAV. Districts with participating farms are coloured in blue.

3. Occurrence of Anaplasma spp. in German Small Ruminant Flocks

In total, antibodies against Anaplasma spp. were detected in 70 out of 71 small ruminant flocks. The IFP ranged between 0% and 97.7%. However, the level of IFP did not differ in principle between the federal states (p > 0.05). There was only one sheep flock in BAV without antibodies to Anaplasma species.

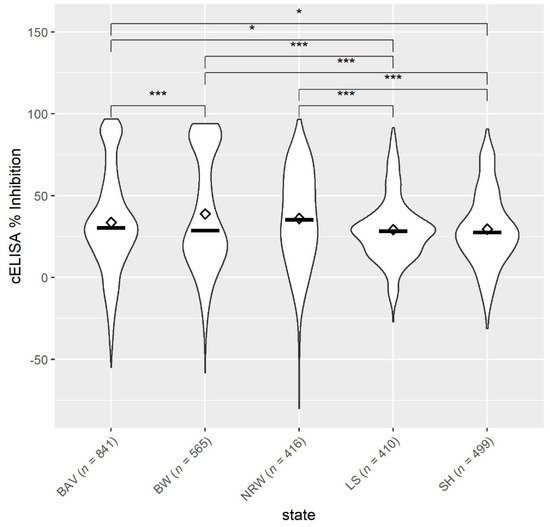

Overall, the mean antibody levels against Anaplasma spp. in sheep from the northern federal states, SH and LS, were significantly lower compared to NRW, BW and BAV (Figure 23). Among the northern federal states, there was no difference in the sheep’s antibody response (p > 0.05). Moreover, the mean antibody levels were also not statistically different between BW vs. NRW and BAV vs. NRW (p > 0.05), but sheep from BAV had significantly lower Anaplasma spp. values than animals from BW.

Figure 23. Mean ◊ and median—values of antibodies to Anaplasma spp. from sheep (n = 2731, 71 flocks) located in five German federal states: BAV = Bavaria, BW = Baden-Wuerttemberg, NRW = North Rhine-Westphalia, LS = Lower Saxony, SH = Schleswig-Holstein. * p < 0.05. *** p < 0.001.

4. Univariable Analysis

4.1. Risk Factors at Animal Level for Exposure to Anaplasma spp.

Sheep had a 2.5 times higher risk acquiring an Anaplasma spp. infection than goats. Females had a 37% increased chance of being seropositive, but the likelihood of antibody detection in young animals (≤2 years) was reduced by one quarter (Supplementary Table S1).

4.2. Risk Factors at Flock Level for Exposure to Anaplasma spp.

At flock level, only landscape conservation and cats had a significant p-value (Supplementary Table S2). Small ruminant flocks used for landscape conservation were four times more likely to have an IFP of above 20%. Farms with cats had an almost four-fold higher risk of having more than 20% IFP than farms without cats.

5. Multivariable Analysis

5.1. Risk Factors at Animal Level for Exposure to Anaplasma spp.

The results of the multivariable analysis were in line with the univariable analysis and revealed no additional information (Table 1).

Table 1.

Multivariable risk factor model at animal level for exposure to

Anaplasma

spp.

| Variable | Category | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value | Quasilikelihood under the Independence Model Criterion (QIC) |

|---|

| Species | Goat | 2.525 | 1.443–4.417 |

| >2 years | |||

| 0.739 | 0.970–0.970 | 0.029 |

5.2. Risk Factors at Flock Level for Exposure to Anaplasma spp.

The resulting multivariate model at flock level included four risk factors (Table 2) which were all significant except for contact to deer.

Table 2. Multivariate risk factor model at flock level for the risk of having an Anaplasma spp. intra-flock seroprevalence of above 20%.

| Variable | Category | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% Confidence Interval | C- p-Value | LR- p-Value | Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) |

|---|

| 0.001 |

| 4342.598 |

| Landscape conservation | No | 5.348 | 1.026–7.877 | 0.047 | 0.0002 | 49.614 | |

| Sex | Male | 1.378 | 1.029–1.846 | 0.032 | |||

| Deer | No | 0.149 | 0.015–1.461 | 0.102 | Age | ||

| Cats | No | 10.731 | 1.681–68.514 | 0.012 | |||

| Dogs | No | 166.328 | 3.606–>999.999 | 0.009 |

Small ruminant flocks which performed landscape conservation had about a five times higher risk of having more than 20% seropositive animals compared to flocks without this farming purpose. Observations of deer near the flock reduced the risk to less than one-sixth, while the presence of cats and dogs on the farms increased the probability of having an IFP above 20% 10-fold and 166-fold, respectively.