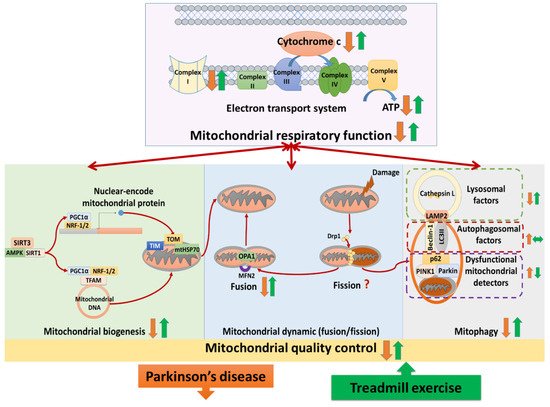

Treadmill training attenuated complex I deficits, cytochrome c release, ATP depletion, and complexes II–V abnormalities in Parkinson’s disease. Studies analyzed the neural mitochondrial quality-control, reporting that treadmill exercise improved mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial fusion, and mitophagy in Parkinson’s disease. The hypothesis that treadmill training could attenuate both neural mitochondrial respiratory deficiency and neural mitochondrial quality-control dysregulation in Parkinson’s disease, suggesting that treadmill training might slow down the progression of Parkinson’s disease.

- treadmill exercise

- Parkinson’s disease

- neural mitochondrial functions

1. Introduction

2. Treadmill Exercise on Neural Mitochondrial Functions in Parkinson’s Disease

2.1. Effects of TE Training on Neural Mitochondrial Respiratory Deficiency in PD

Three studies analyzed the effects of TE training on mitochondrial complex I in PD [15][17][18][15,23,26]. Two of those showed that the protein levels of complex I were reduced in PD compared to normal, whereas TE training enhanced their levels in PD [15][18][15,26]. However, the other study observed that the protein levels of complex I were similar among the normal control group, the PD group, and the TE-trained PD group [17][23]. Two studies observed that the protein levels of cytochrome c in neural mitochondria were reduced in PD compared to normal, whereas TE training increased those levels in PD [19][20][20,24]. One study reported that ATP production was reduced in PD compared to normal, whereas TE training enhanced ATP production in PD [21][25]. Five authors accessed the expression of complexes II, III, IV, and V, reporting different results [15][19][22][17][18][15,20,21,23,26]. One study reported that the protein levels of complexes II, III, IV, and V were unchanged among the normal control group, the sedentary PD group, and the TE-trained PD group [18][26]. The other study showed that the protein levels of complex II and complex V were reduced in PD compared to normal and those levels were restored by TE training in PD, whereas the protein levels of complex III and complex IV were unchanged among the normal control group, the PD group, and the TE-trained PD group [17][23]. Another study observed that TE training reduced the overexpression of complex II, complex III, and complex IV protein levels in PD, whereas complex V protein levels were unchanged among the normal control group, the PD group, and the TE trained-PD group [15]. Two studies showed that the protein levels of complex IV were reduced in PD compared to normal, whereas TE training increased those levels in PD [19][22][20,21].2.2. Effects of TE Training on Neural Mitochondrial Biogenesis in PD

Six publications analyzed TE effects on biogenesis regulators of neural mitochondria in PD [16][19][23][17][20][18][16,20,22,23,24,26]. Four of those showed that the protein levels of biogenesis regulators, including SIRT3 [17][23], SIRT1 [16][19][16,20], PGC-1α [19][18][20,26], NRF-1,2 [19][17][18][20,23,26], and TFAM [19][17][18][20,23,26] were reduced in PD compared to normal, whereas TE training increased those levels in PD. In the other study that analyzed mRNA and protein levels of biogenesis regulators, they observed reduced levels of two biogenesis regulators (AMPK and PGC-1α) along with increased levels of two others (SIRT1 and TFAM) in PD compared to normal [23][22]. However, in this study, all of those levels were enhanced by TE training in PD [23][22]. On the contrary, another study showed that the mRNA levels of biogenesis regulators (PGC-1α and TFAM) were increased in PD compared to normal, and those levels were reduced by TE training in PD [20][24]. Two studies analyzed the effects of TE on translocase factors of neural mitochondria in PD [15][22][15,21]. One study reported that the protein levels of translocase proteins (TOM-20, TOM-40, TIM-23, and mtHSP70) were reduced in PD compared to normal, whereas TE training increased those levels in PD [22][21]. The other study showed that the level of translocase protein (TOM-20) in the substantia nigra was reduced in PD and recovered by TE training, but its level in the striatum was similar among the normal control group, the PD group and the TE-trained PD group [15].2.3. Effects of TE Training on Neural Mitochondrial Dynamics in PD

Two studies analyzed the effects of TE training on mitochondrial fusion and fission proteins [15][17][15,23]. They reported that the protein levels of fusion proteins (OPA1, MFN2) were reduced in PD compared to normal, whereas TE training enhanced those levels in PD [15][17][15,23]. Regarding neural mitochondrial fission, one of two studies showed that the fission protein (Drp-1) was reduced in PD compared to normal, whereas TE training enhanced those levels in PD [15]. However, the other study showed that the anti-fission protein level (p-Drp1Ser637) was reduced in PD compared to normal, whereas TE training enhanced those levels in PD [17][23].2.4. Effects of TE Training on Neural Mitophagy in PD

Three studies analyzed the effects of TE training on neural mitophagy in PD [15][19][24][15,20,27]. Those studies showed that the levels of mitophagy detector proteins, including PINK1 [15][24][15,27], parkin [24][27], and p62 [19][24][20,27] were increased in PD compared to normal, whereas TE training reduced those levels in PD. Two of those studies showed that the levels of autophagosomal proteins, including beclin-1 [19][20] and LC3 II/I [19][24][20,27] were increased in PD compared to normal, whereas TE training had no effect on their levels in PD. One of those studies reported that the levels of lysosomal proteins (LAMP2 and cathepsin L) were reduced in PD compared to normal, whereas TE training enhanced those levels in PD [24][27].3. Summary

(1) Treadmill training attenuated neural mitochondrial respiratory deficiency in Parkinson’s disease, supported by the evidence that treadmill training normalized the levels of complexes I–V, cytochrome c, and ATP production in the Parkinsonian brain. (2) Treadmill training optimized neural mitochondrial biogenesis in Parkinson’s disease, supported by the evidence that treadmill training increased or normalized the levels of biogenesis regulators (SIRT3, SIRT1, AMPK, PGC-1α, NRF-1,2, and TFAM) and import machinery (TOM-20, TOM-40, TIM-23, and mtHSP70) in the Parkinsonian brain. (3) Treadmill training enhanced the neural mitochondrial fusion in Parkinson’s disease, supported by the evidence that treadmill training increased mitochondrial fusion factors (OPA-1 and MFN-2) in the Parkinsonian brain. (4) Treadmill training repaired the impairment of mitophagy in Parkinson’s disease, supported by the evidence that treadmill training reduced the levels of dysfunctional mitochondria detectors (PINK1, parkin, and p62) and increased the levels of lysosomal factors (LAMP2 and cathepsin L) in the Parkinsonian brain. Taking these findings with the previously hypothesized pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease together, we drew a hypothesized figure (Figure 12), which suggests that treadmill training could counteract the neurodegeneration of Parkinson’s disease in both the neural mitochondrial respiratory system and neural mitochondrial quality-control.

4. The Implications for Future Research

Further interdisciplinary studies are required to investigate the effects of treadmill training on the neural mitochondrial respiratory system, biogenesis, dynamics, and mitophagy in both genetic models and toxin models of Parkinson’s disease. Additionally, clinical studies should clarify the possible therapeutic applications through different exercise interventions into neural mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease.