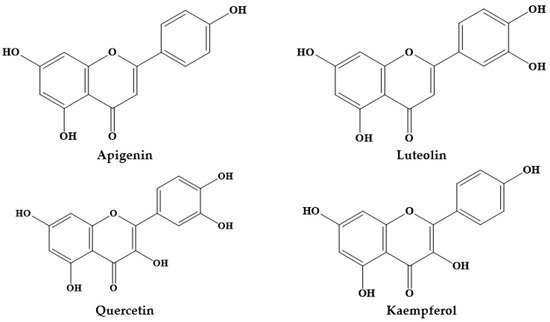

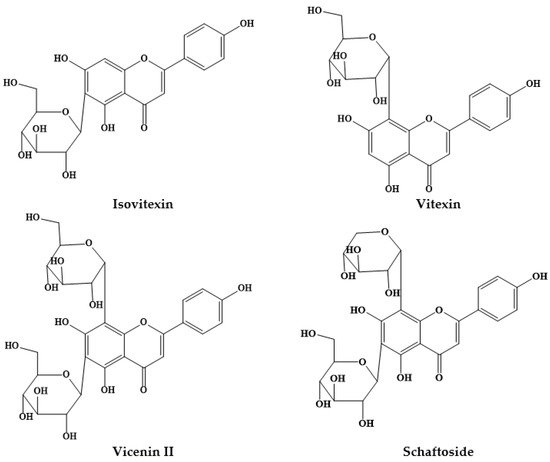

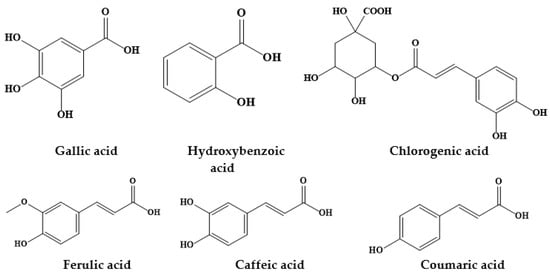

Members of the Prosopis genus are native to America, Africa and Asia, and have long been used in traditional medicine. The Prosopis species most commonly used for medicinal purposes are P. africana, P. alba, P. cineraria, P. farcta, P. glandulosa, P. juliflora, P. nigra, P. ruscifolia and P. spicigera, which are highly effective in asthma, birth/postpartum pains, callouses, conjunctivitis, diabetes, diarrhea, expectorant, fever, flu, lactation, liver infection, malaria, otitis, pains, pediculosis, rheumatism, scabies, skin inflammations, spasm, stomach ache, bladder and pancreas stone removal. Flour, syrup, and beverages from Prosopis pods have also been potentially used for foods and food supplement formulation in many regions of the world. In addition, various in vitro and in vivo studies have revealed interesting antiplasmodial, antipyretic, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticancer, antidiabetic and wound healing effects. The phytochemical composition of Prosopis plants, namely their content of C-glycosyl flavones (such as schaftoside, isoschaftoside, vicenin II, vitexin and isovitexin) has been increasingly correlated with the observed biological effects.

- Prosopis

- vitexin

- C-glycosyl flavones

- food preservative

- antiplasmodial

- wound healing potential

1. Introduction

2. Prosopis Plants Phytochemical Composition

| Prosopis Plant and Part | Identified/Quantified Phytochemicals | References |

|---|---|---|

| P. alba flours | Isovitexin (1.12–0.48 μg/mg) | [9] |

| Vicenin II (1.07–0.34 μg/mg) | ||

| Vitexin (0.91–0.47 μg/mg) | ||

| Schaftoside (0.42–0.00 μg/mg) | ||

| Ferulic acid (4.01–0.28 μg/mg) | ||

| Coumaric acid (3.94–0.33 μg/mg) | ||

| P. alba pods | Q-dihexoside rhamnoside | [10] |

| Q-dihexoside | ||

| Q-methylether dihexoside | ||

| Vitexin | ||

| Q-rhamnoside hexoside | ||

| Isovitexin | ||

| Q-hexoside | ||

| K-hexoside | ||

| P. alba flour | Isoschaftoside hexoside (2.43 mg/g) | [13] |

| Schaftoside hexoside (3.33 mg/g) | ||

| Vicenin II/Isomer (0.67 mg/g) | ||

| Vicenin II/Isomer (2.34 mg/g) | ||

| Gallic acid (8.203 mg/g) | ||

| [ | ||

| 21 | ||

| ] | ||

| Hydroxybenzoic acid (1.797 mg/g) | ||

| Pyrocatechol (5.538 mg/g) | ||

| Caffeic acid (0.295 mg/g) | ||

| Ferulic acid (0.466 mg/g) | ||

| Quercetin (0.045 mg/g) | ||

3. Traditional Medicinal Uses of Prosopis Plants

| Scientific Name | Location | Local Name | Parts Used | Administration | Disease(s) Treated/Bioactive Effects | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. africana | Sélingué subdistrict, Mali | Guele | Bark trunk | Oral, Bath | Malaria | [19] | ||

| Guinea-Bissau | Tentera, Buiengué, Bussagan, Coquengue karbon, Késeg-késeg, Paucarvão, Pócarvão, Pó-de-carbom, Po-di-carvom, Tchelem, Tchalem-ai, tchela, Tchelangadje, Tchelem, Bal-tencali, Culengô, Culim-ô, Djandjam-ô, Quéssem-quéssem, Djeiha, Ogea | Leaves, bark, roots | Unspecified | Pains, pregnancy (childbirth, breastfeeding, diseases of the newborn), skin inflammations (wounds, burns) | [20] | |||

| Nsukka Local Government Area, South-eastern Nigeria | Ugba | Leaf | Oral | Malaria | [21] | |||

| North-West Nigeria | Kirya, Ko-hi | Roots | Oral | Analgesic, anti-inflammatory | [22] | |||

| P. alba | Wichí people of Salta province, Argentina | Jwaayukw, Algarrobo blanco | Resin | Oral | Conjunctivitis, post-abortion pain | [23] | ||

| P. cineraria | Bahawalnagar, Punjab, Pakistan | Drucey | Leaves, stem | Oral | Spasm, diabetes, liver infection, diarrhea, removal of bladder and pancreas stone, fever, flu | [5] | ||

| Topical | Rheumatism | |||||||

| Thar Desert (Sindh), Pakistan | Gujjo | Fruit | Oral | Tonic for body, leucorrhea | [13] | |||

| South of Kerman, Iran | Kahour | Fruit | Topical | Asthma, skin rash | [14] | |||

| Pakistan | Unspecified | Flower | Oral | Rheumatism | [15] | |||

| Hafizabad district, Punjab, Pakistan | Jhand | Leaf, bark, stem, flower, fruit | Oral, topical, eye drop | Liver tonic, boils and blisters, scorpion bite, pancreatic stone, leucorrhoea, chronic dysentery, cataract | [3] | |||

| Pakistan | Unspecified | Fruit, pods | Unspecified | Asthma | [4] | |||

| Pakistan | Jandi, Kanda, Kandee, Jhand | Leaves, Bark, Flowers, Pods and wood | Oral | Menstrual disorders, contraceptive, prevention of abortion | [16] | |||

| P. farcta | Jahrom, Iran | Kourak | Fruit | Oral | Constipation, febrifuge | [24] | ||

| P. glandulosa Torr | Bustamante, Nuevo León, Mexico | Mezquite | Inflorescences | Oral | Stomach pain | [25] | ||

| P. juliflora | Thar Desert (Sindh), Pakistan | Devi | Leaves, Gum | Oral | Painkiller, boils opening, eye inflammation, body tonic, muscular pain | [13] | ||

| Isoschaftoside (23.67 mg/g) | ||||||||

| Hafizabad district, Punjab, Pakistan | Mosquit pod | Whole plant, Flower, Stem, Leaves, Bark | Oral, topical, and as toothbrush | Galactagogue, kidney stones, toothache, breast cancer, asthma, boils | [3 | Schaftoside (14.86 mg/g) | ||

| ] | ||||||||

| Pakistan | Unspecified | Xerophytic shrub | Unspecified | Vitexin (0.46 mg/g) | ||||

| Isovitexin (2.09 mg/g) | ||||||||

| Asthma, cough | [ | 4 | ] | |||||

| Mohmand Agency, FATA, Pakistan | Kikrye | Leaves | Oral | Lactation, expectorant | [17] | |||

| Western Madhya Pradesh, India | Reuja | Stem bark | Oral | Asthma | [18] | P. alba | ||

| P. nigra | Wichí people of Salta province, Argentina | Wosochukw, Algarrobo negro | Resin | Oral | Ocular trauma, conjunctivitis | [23] | exudate gum | |

| P. ruscifolia | Wichí people of Salta province, Argentina | Atek, Vinal | LeavesFerulic acid 4-glucuronide (E) | [11] | ||||

| Apigetrin, chrysin (E) | ||||||||

| Chlorogenic acid (E and NE) | ||||||||

| 3-O-feruloylquinic acid (E) | ||||||||

| p-Coumaroylquinic acid (E) | ||||||||

| Valoneic acid dilactone (E) | ||||||||

| Digallic acid (E) | ||||||||

| Ferulic acid (NE) | ||||||||

| Esculetin derivative (NE) | ||||||||

| 7-O-Methylapigenin (NE) | ||||||||

| P. nigra pods | Cyanidin rhamnosyl hexoside | [10] | ||||||

| Cyanidin-3-hexoside | ||||||||

| Peonidin-3-hexoside | ||||||||

| Malvidin dihexoside | ||||||||

| Cyanidin malonoyl hexoside | ||||||||

| Petunidin-3-hexoside | ||||||||

| Malvidin rhamnosyl hexoside | ||||||||

| Malvidin-3-hexoside | ||||||||

| Vicenin II | ||||||||

| Q-dihexoside rhamnoside | ||||||||

| Isoschaftoside | ||||||||

| Q-dihexoside | ||||||||

| Schaftoside | ||||||||

| Q-hexoside rhamnose | ||||||||

| K-hexoside rhamnoside | ||||||||

| Isovitexin | ||||||||

| Q-hexoside | ||||||||

| K-hexoside | ||||||||

| Apigenin hexoside rhamnoside | ||||||||

| Q methyl ether hexoside rhamnoside | ||||||||

| Oral | K-methyl ether hexoside rhamnoside | |||||||

| P. nigra flour | Vicenin II (0.34 μg/mg) | [14] | ||||||

| Schaftoside (0.24 μg/mg) | ||||||||

| Isoschaftoside (0.27 μg/mg) | ||||||||

| Isovitexin (0.81 μg/mg) | ||||||||

| Protocatechuic acid (0.33 μg/mg) | ||||||||

| Coumaric acid (8.16 μg/mg) | ||||||||

| Ferulic acid (4.47 μg/mg) | ||||||||

| Conjunctivitis, stomachache, pimples/rash, scabies, callouses, fever, birth/postpartum pains, diarrhoea, pediculosis, otitis | [ | 23 | ] | |||||

| P. spicigera | Pakistan | Unspecified | Bark, leaves, flowers | Unspecified | Asthma | P. cineraria | Protocatechuic acid (31.65 mg/g) Chlorogenic acid (22.31 mg/g) | [15,16,17][15][16][17] |

| Caffeic acid (6.02 mg/g) | ||||||||

| Ferulic acid (9.24 mg/g) | ||||||||

| Prosogerin A, B, C and D | ||||||||

| β-sitosterol | ||||||||

| Hentriacontane | ||||||||

| Rutin | ||||||||

| Gallic acid | ||||||||

| Patulitrin | ||||||||

| Luteolin | ||||||||

| [ | Spicigerin | |||||||

| 4 | P. laevigata | Gallic acid (8–25 mg/100 g) | [18] | |||||

| Coumaric acid (335–635 mg/100 g) | ||||||||

| Catechin (162.5 mg/100g) | ||||||||

| Gallocatechin (340–648 mg/100 g) | ||||||||

| Epicatechin gallate (10–71 mg/100 g) | ||||||||

| Rutin (222.4–256.1 mg/100 g) | ||||||||

| Morin (236.5 mg/100 g) | ||||||||

| ] | Naringenin (20 mg/100 g) | |||||||

| Luteolin (13 mg/100 g) | ||||||||

| P. juliflora | 4′-O-Methylgallocatechin | [19,20][19][20] | ||||||

| (+)-catechins | ||||||||

| (-)-mesquitol | ||||||||

| Apigenin | ||||||||

| Luteolin | ||||||||

| Apigenin-6,8-di-C-glycoside | ||||||||

| Chrysoeriol 7-O-glucoside | ||||||||

| Luteolin 7-O-glucoside | ||||||||

| Kaempferol 3-O-methyl ether | ||||||||

| Quercitin 3-O-methyl ether | ||||||||

| Isoharmentin 3-O-glucoside | ||||||||

| Isoharmentin 3-O-rutinoside | ||||||||

| Quercitin 3-O-rutinoside | ||||||||

| Quercitin 3-O-diglycoside | ||||||||

| P. glandulosa |

3.1. Prosopis cineraria

3.2. Prosopis juliflora

3.3. Prosopis africana

3.4. Other Prosopis Plants

References

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Salehi, B.; Varoni, E.M.; Sharopov, F.; Yousaf, Z.; Ayatollahi, S.A.; Kobarfard, F.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Afdjei, M.H.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; et al. Plants of the Melaleuca genus as antimicrobial agents: From farm to pharmacy. Phytother. Res. 2017.

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Roberts, T.H.; Matthews, K.R.; Bezerra, C.F.; Morais-Braga, M.F.B.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; Sharopov, F.; Salehi, B.; Yousaf, Z.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; et al. Ethnobotany of the genus Taraxacum—Phytochemicals and antimicrobial activity. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 2131–2145.

- Umair, M.; Altaf, M.; Abbasi, A.M. An ethnobotanical survey of indigenous medicinal plants in Hafizabad district, Punjab-Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177912.

- Younis, W.; Asif, H.; Sharif, A.; Riaz, H.; Bukhari, I.A.; Assiri, A.M. Traditional medicinal plants used for respiratory disorders in Pakistan: A review of the ethno-medicinal and pharmacological evidence. Chin. Med. 2018, 13, 48.

- Ahmed, N.; Mahmood, A.; Ashraf, A.; Bano, A.; Tahir, S.S.; Mahmood, A. Ethnopharmacological relevance of indigenous medicinal plants from district Bahawalnagar, Punjab, Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 175, 109–123.

- Abarca, N.A.; Campos, M.G.; Reyes, J.A.A.; Jimenez, N.N.; Corral, J.H.; Valdez, L.G.S. Antioxidant activity of polyphenolic extract of monofloral honeybee-collected pollen from mesquite (Prosopis juliflora, Leguminosae). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2007, 20, 119–124.

- Cattaneo, F.; Sayago, J.E.; Alberto, M.R.; Zampini, I.C.; Ordoñez, R.M.; Chamorro, V.; Pazos, A.; Isla, M.I. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities, functional properties and mutagenicity studies of protein and protein hydrolysate obtained from Prosopis alba seed flour. Food Chem. 2014, 161, 391–399.

- Jahromi, M.A.F.; Etemadfard, H.; Zebarjad, Z. Antimicrobial and antioxidant characteristics of volatile components and ethanolic fruit extract of Prosopis farcta (Bank & Soland.). Trends Pharm. Sci. 2018, 4, 177–186.

- Rodriguez, I.F.; Pérez, M.J.; Cattaneo, F.; Zampini, I.C.; Cuello, A.S.; Mercado, M.I.; Ponessa, G.; Isla, M.I. Morphological, histological, chemical and functional characterization of Prosopis alba flours of different particle sizes. Food Chem. 2019, 274, 583–591.

- Perez, M.J.; Cuello, A.S.; ZampiniI, C.; Ordonez, R.M.; Alberto, M.R.; Quispe, C.; Schmeda-Hirschmann, G.; Isla, M.I. Polyphenolic compounds and anthocyanin content of Prosopis nigra and Prosopis albapods flour and their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capacities. Food Res. Int. 2014, 64, 762–771.

- Vasile, F.E.; Romero, A.M.; Judis, M.A.; Mattalloni, M.; Virgolini, M.B.; Mazzobre, M.F. Phenolics composition, antioxidant properties and toxicological assessment of Prosopis alba exudate gum. Food Chem. 2019.

- Afrin, S.; Gasparrini, M.; Forbes-Hernandez, T.Y.; Reboredo-Rodriguez, P.; Mezzetti, B.; Varela-Lopez, A.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. Promising health benefits of the strawberry: A focus on clinical studies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 4435–4449.

- Yaseen, G.; Ahmad, M.; Sultana, S.; Alharrasi, A.S.; Hussain, J.; Zafar, M. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants in the Thar Desert (Sindh) of Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 163, 43–59.

- Sadat-Hosseini, M.; Farajpour, M.; Boroomand, N.; Solaimani-Sardou, F. Ethnopharmacological studies of indigenous medicinal plants in the south of Kerman, Iran. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 199, 194–204.

- Suroowan, S.; Javeed, F.; Ahmad, M.; Zafar, M.; Noor, M.J.; Kayani, S.; Javed, A.; Mahomoodally, M.F. Ethnoveterinary health management practices using medicinal plants in South Asia—A review. Vet. Res. Commun. 2017, 41, 147–168.

- Tariq, A.; Adnan, M.; Iqbal, A.; Sadia, S.; Fan, Y.; Nazar, A.; Mussarat, S.; Ahmad, M.; Olatunji, O.A.; Begum, S. Ethnopharmacology and toxicology of Pakistani medicinal plants used to treat gynecological complaints and sexually transmitted infections. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 114, 132–149.

- Aziz, M.A.; Adnan, M.; Khan, A.H.; Shahat, A.A.; Al-Said, M.S.; Ullah, R. Traditional uses of medicinal plants practiced by the indigenous communities at Mohmand Agency, FATA, Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14, 2.

- Wagh, V.V.; Jain, A.K. Status of ethnobotanical invasive plants in western Madhya Pradesh, India. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 114, 171–180.

- Diarra, N.; van’t Klooster, C.; Togola, A.; Diallo, D.; Willcox, M.; de Jong, J. Ethnobotanical study of plants used against malaria in Sélingué subdistrict, Mali. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 166, 352–360.

- Catarino, L.; Havik, P.J.; Romeiras, M.M. Medicinal plants of Guinea-Bissau: Therapeutic applications, ethnic diversity and knowledge transfer. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 183, 71–94.

- Odoh, U.E.; Uzor, P.F.; Eze, C.L.; Akunne, T.C.; Onyegbulam, C.M.; Osadebe, P.O. Medicinal plants used by the people of Nsukka Local Government Area, south-eastern Nigeria for the treatment of malaria: An ethnobotanical survey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 218, 1–15.

- Salihu, T.; Olukunle, J.O.; Adenubi, O.T.; Mbaoji, C.; Zarma, M.H. Ethnomedicinal plant species commonly used to manage arthritis in North-West Nigeria. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 118, 33–43.

- Suárez, M.E. Medicines in the forest: Ethnobotany of wild medicinal plants in the pharmacopeia of the Wichí people of Salta province (Argentina). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 231, 525–544.

- Nasab, F.K.; Esmailpour, M. Ethno-medicinal survey on weed plants in agro-ecosystems: A case study in Jahrom, Iran. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 21, 2145–2164.

- Estrada-Castillón, E.; Villarreal-Quintanilla, J.Á.; Rodríguez-Salinas, M.M.; Encinas-Domínguez, J.A.; González-Rodríguez, H.; Figueroa, G.R.; Arévalo, J.R. Ethnobotanical survey of useful species in Bustamante, Nuevo León, Mexico. Hum. Ecol. 2018, 46, 117–132.