Many Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria rely on a functional type III secretion system (T3SS), which injects multiple effector proteins into eukaryotic host cells, for their pathogenicity. Genetic studies conducted in different host-microbe pathosystems often revealed a sophisticated regulatory mechanism of their T3SSs, suggesting that the expression of T3SS is tightly controlled and constantly monitored by bacteria in response to the ever-changing host environment.

- T3SS

- plant bacterial diseases

- Dickeya dadantii

- fire blight

- T3SS inhibitors

- c-di-GMP

1. Introduction

Type III secretion systems (T3SSs) are well-studied protein secretion/translocation systems found in almost all Gram-negative bacterial pathogens of plants and animals [1][2][1,2]. Structurally, the T3SSs are highly conserved among bacteria. They are syringe-like nanomachines consisting of inner and outer membrane rings, known as a basal body, and an apparatus that enables bacteria to inject diverse effector proteins directly into the host cell cytoplasm, which participate in the regulation of host cell functions to benefit the bacterial survival and multiplication [3][4][3,4]. In the plant pathogenic bacteria, the T3SSs have attracted much attention due to their ability to elicit the hypersensitive response (HR), a plant defense mechanism characterized by rapid cell death, in resistant or non-host plants and induce disease symptoms in host plants [4][5][4,5]. In Erwinia amylovora, for instance, the T3SS is a major pathogenicity factor as the T3SS-deficient mutants are unable to cause fire blight disease in Rosaceous plant hosts [6][7][6,7]. Studies of the T3SS from Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000, which causes bacterial speck of tomato and the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, have provided valuable information for the understanding of host–microbe interactions by signifying the T3SS and its effectors as essential players involved in the repression of plant defense mechanisms during the bacterial infection [8][9][10][8,9,10].

As is the case for many T3SS-expressing pathogens, a growing number of studies have explored novel disease management strategies using the T3SS as a target for the inhibition of bacterial pathogenesis [11][12][13][11,12,13]. In the studies of plant pathogenic bacteria, small molecules that target and inhibit the T3SSs have been discovered. The soft rot plant pathogen Dickeya dadantii served as the model organism due to its well-characterized regulatory pathways of the T3SS. It has been well established that the T3SSs from plant pathogenic bacteria are encoded by the hypersensitive response and pathogenicity (hrp) operon [14]. Based on the similarities of operon organization and regulatory systems, plant pathogenic bacterial hrp gene clusters are divided into two groups [15][16][15,16]. The group I hrp gene cluster includes those of P. syringae, E. amylovora, and Dickeya spp., in which the alternative sigma factor HrpL is the master regulator that activates the expression of most hrp genes [17][18][19][17,18,19]. Ralstonia spp. and Xanthomonas spp. possess the group II hrp gene clusters, whose expression is heavily relied on an AraC-type transcriptional activator HrpX [20][21][20,21]. Genetic and molecular analyses have identified multiple important regulators that control the expression of T3SS in plant pathogenic bacteria, suggesting that the regulation of T3SS is a highly modulated process during the infection of plants by pathogens, and such regulation often occurs in a hierarchical manner.

2. Regulation of T3SS in D. dadantii

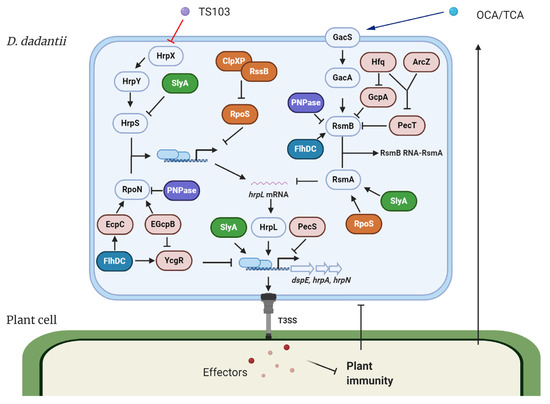

The expression of T3SS in D. dadantii is governed by the master regulator HrpL. This alternative sigma factor activates T3SS gene expression by binding to the highly conserved hrp box (GGAACC-N15/16-CCACNNA) in their promoter regions. Genes such as hrpA, hrpN, and dspE, which encode the T3SS pilus protein, a harpin, and a virulence effector, respectively, are all transcribed in a HrpL-dependent manner [17][18][22][23][17,18,27,28]. The regulation of HrpL is achieved via two independent regulatory cascades in D. dadantii (Figure 1) [24][25][26][27][29,30,31,32]. Transcriptionally, HrpS is a σ54 (RpoN) enhancer binding protein, which binds the σ54 (RpoN)-containing RNA polymerase holoenzyme and initiates the expression of hrpL. A two-component signal transduction system (TCSTS) HrpX/HrpY is responsible for the activation of hrpS [24][28][29,33]. Post-transcriptionally, hrpL is regulated by RsmA, a small RNA-binding protein, which binds the 5′ untranslated region of hrpL mRNA and facilitates its degradation [29][34]. RsmB is a non-coding RNA containing multiple RsmA binding sites that bind RsmA proteins to antagonize their negative effect on hrpL mRNA, resulting in a positive effect on the downstream T3SS gene expression [28][30][33,35]. The GacS/GacA TCSTS has been shown to upregulate the production of RsmB RNA in D. dadantii [26][31].

Figure 1. Model of the type III secretion system (T3SS) regulation and modes of action of T3SS inhibitors in Dickeya dadantii. The expression of T3SS master regulator HrpL is transcriptionally regulated by the HrpX/HrpY-HrpS-RpoN pathway and post-transcriptionally regulated by the GacS/GacA-RsmB-RsmA pathway. Several transcriptional regulators, including FlhDC, SlyA, PecS, PecT, and RpoS, regulate the expression of T3SS genes via targeting multiply key components in the T3SS regulatory pathways. Hfq and its dependent sRNA ArcZ form a feed-forward signaling cascade that positively control the expression of RsmB. PNPase degrades RsmB sRNA and is also required for the stability of rpoN mRNA. c-di-GMP signaling is involved in the FlhDC-mediated RpoN regulation and the Hfq-mediated RsmB regulation. T3SS injects bacterial effectors into the plant cells to suppress plant immune responses. On the other hand, plants secrete a variety of phenolic compounds that are able to regulate the T3SS in bacteria. For D. dadantii, two plant phenolic compounds, o-coumaric acid (OCA) and t-cinnamic acid (TCA), upregulate T3SS gene expression via the GacS/GacA-RsmB-RsmA-HrpL pathway. Trans-4-hydroxycinnamohdroxamic acid (TS103), a plant phenolic compound derivative, represses the expression of T3SS via the HrpX/HrpY-HrpS-RpoN-HrpL pathway. ⊥ represents negative control; → represents positive control.

3. Discovery of T3SS Inhibitors in Plant Pathogens and Their Regulatory Mechanisms

Small molecules that could specifically inhibit the synthesis or functionality of the T3SS are referred to as T3SS inhibitors. Unlike traditional antibiotics that often target bacterial survival, T3SS inhibitors display negligible effects on bacterial growth, thus reducing the selective pressure for the development of resistance [12][31][32][12,113,114]. In plant pathogenic bacteria, extensive studies have led to the discovery of a group of plant-derived compounds and several chemically synthesized compounds that modulate the expression of T3SS in major plant pathogens

3.1. Plant Phenolic Compounds as T3SS Inhibitors

Plant phenolic compounds are one of the most widespread secondary metabolites in plants. They range from low molecular weight and single aromatic ringed compounds to large and complex-polyphenols and are involved in diverse physiological activities in plants, such as pigmentation, growth, and defense mechanisms [33][123]. Plant phenolic compounds also function as signal molecules that either induce or repress the microbial gene expression during the interactions between plants and microbes [34][124]. As the expression of D. dadantii T3SS genes was induced in planta [35][125], Yang et al. discovered that two plant phenolic compounds, o-coumaric acid and t-cinnamic acid, positively regulated the expression of T3SS genes in D. dadantii [27][32]. o-coumaric acid upregulated hrpL at the post-transcriptional level via the RsmA/RsmB system and had no impact on the HrpX/HrpY-HrpS-HrpL pathway. Although o-coumaric acid and t-cinnamic acid are the biosynthetic precursors of salicylic acid, which plays an important role in plant defense responses [36][37][126,127], application of salicylic acid did not affect the expression of T3SS in D. dadantii [27][32].

To identify potential phenolic compounds as T3SS inhibitors, Li and colleagues evaluated the effects of 29 analogs and isomers of o-coumaric acid and t-cinnamic acid on the transcriptional activity of hrpA:gfp fusion in D. dadantii. One compound, p-coumaric acid, was shown to repress the expression of T3SS genes via the HrpS-HrpL pathway, as the addition of 100 µM p-coumaric acid significantly reduced the transcriptional activities and mRNA levels of hrpS and hrpL without affecting the bacterial growth [38][117]. p-coumaric acid is an intermediate in the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway. Phenylpropanoids are plant secondary metabolites that act as defense molecules in response to microbial attack [39][40][128,129]. It is worth noting that the discovery of p-coumaric acid as a T3SS inhibitor has provided fundamental aspects for compound modification and greatly encouraged the innovation of chemically synthesized plant phenolic compound derivatives. A subsequent library screening of 50 p-coumaric acid derivatives identified trans-4-hydroxycinnamohydroxamic acid as a T3SS inhibitor in D. dadantii. The same study found that this synthetic compound increased the inhibitory potency towards T3SS by eightfold compared with the naturally occurring p-coumaric acid [41][118]. Furthermore, trans-4-hydroxycinnamohydroxamic acid was shown to repress hrpL transcriptionally through both the RpoN-HrpL pathway and the HrpX/HrpY-HrpS-HrpL pathway. Trans-4-hydroxycinnamohydroxamic acid repressed rsmB via unknown mechanisms, negatively contributing to the post-transcriptionally regulation of hrpL [41][118].

Using similar strategies as Li et al. [38][41][117,118], Khokhani and colleagues reported several plant phenolic compounds and derivatives that can modulate T3SS in E. amylovora [42][115]. o-coumaric acid and t-cinnamic acid, which induced the expression of T3SS in D. dadantii [27][32], repressed the E. amylovora T3SS. The T3SS inhibitors of E. amylovora also include benzoic acid, salicylic acid, and 4-methoxy-cinnamic acid. Benzoic acid negatively regulated hrpS expression, while 4-methoxy-cinnamic acid repressed HrpL, respectively. HR analysis demonstrated that co-infiltration of E. amylovora with benzoic acid or 4-methoxy-cinnamic acid reduced the HR development in Nicotiana tabacum cv. Xanthi leaves, suggesting that both phenolic compounds are functionally inhibiting T3SS in planta. Earlier studies on phenylpropanoid metabolism in Vanilla planifolia have reported that 4-methoxy-cinnamic acid is one of the intermediates in the biosynthetic conversion of cinnamic acid to benzoic acid [43][130]. Benzoic acid could be produced via the conversion of t-cinnamic acid to salicylic acid [44][131].

X. oryzae pv. oryzae is the causal agent of bacterial blight, one of the major rice diseases in the world. X. oryzae pv. oryzicola, which causes the bacterial leaf streak disease, is another rice pathogen [45][132]. Both pathogens process a T3SS encoded by the group II hrp gene clusters, in which HrpG and HrpX are two key regulators [16][21][25][46][16,21,30,133]. HrpG is a response regulator of the OmpR family of TCSTS, which positively regulates the expression of hrpX. HrpX is an AraC family transcriptional regulator responsible for activating the transcription of hrp genes [21][46][21,133]. By combining the transcriptional screening of the T3SS genes and HR assay in tobacco, Fan et al. identified four plant phenolic compounds, including o-coumaric acid, trans-2-methoxycinnamic acid, trans-2-phenylcyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid, and trans-2-methylcinnamic acid, actively inhibited the T3SS gene expression in vitro likely through the HrpG-HrpX regulatory cascade. Application of these T3SS inhibitors reduced the HR of X. oryzae pv. oryzae in non-host plants and the water soaking and disease symptoms of the pathogen in rice [47][116]. Since no impact on other virulence factors of X. oryzae pv. oryzae, such as the type II secretion system (T2SS), exopolysaccharide (EPS), and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [48][49][134,135], was observed, the reduced virulence caused by the plant phenolic compounds in X. oryzae pv. oryzae is T3SS-dependent. A recent study was conducted to further understand the response of X. oryzae pv. oryzae to o-coumaric acid using transcriptomic analysis [50][136].

In R. solanacearum, the bacterial wilt pathogen of tomato, much progress has been made in identifying coumarins as T3SS inhibitors. Coumarins, consisting of fused benzene and α-pyrone rings, are a family of plant-derived secondary metabolites containing a large class of phenolic substances [51][137]. Members of the coumarins have been extensively studied mainly for their antimicrobial properties [52][138]. Umbelliferone is a 7-hydroxycoumarin that has recently been reported to repress the expression of hrpG and multiple T3SS regulon genes in R. solanacearum [53][54][119,120]. It reduced biofilm formation and suppressed the wilting disease process by reducing the colonization and proliferation of R. solanacearum in planta [54][120]. Besides, six plant phenolic compounds and derivatives, including p-coumaric acid, that repress the T3SS in D. dadantii, failed to modulate the expression of R. solanacearum T3SS genes [55][122].

3.2. Salicylidene Acylhydrazides and Their Derivatives as T3SS Inhibitors

Salicylidene acylhydrazides are one of the earliest T3SS inhibitors that were first identified through large-scale chemical screening approaches in Yersinia spp. [56][57][58][139,140,141]. Later studies have shown that salicylidene acylhydrazide family compounds actively against T3SSs from other human pathogenic bacteria, including S. enterica, Shigella, Chlamydia, P. aeruginosa, and enteropathogenic E. coli [59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150]. However, whether salicylidene acylhydrazides inhibit the plant pathogenic bacterial T3SSs remained unknown. To address this question, Yang and colleagues screened a small library of compounds. They found that several salicylidene acylhydrazides repressed the expression of T3SS genes, including the master regulator encoding gene hrpL, in E. amylovora [68][121]. Microarray analysis of E. amylovora treated with compound 3, also known as ME0054 [benzoic acid N′-(2,3,4-trihydroxy-benzylidene)-hydrazide] [58][141], confirmed its inhibitory impact on T3SS, as the majority of the 38 known T3SS genes was downregulated [68][121]. In addition, compound 3 suppressed the production of EPS amylovoran, one of the major pathogenicity factors of E. amylovora [7][69][7,151], and reduced the disease development of E. amylovora on crab apple flowers [68][121].

Puigvert and colleagues recently applied a similar approach to the T3SS of R. solanacearum to discover T3SS inhibitors [55][122]. Three synthetic salicylidene acylhydrazide derivatives, ME0054, ME0055 [4-nitrobenzoic acid N′-(2,4-dihydroxy-benzylidene)-hydrazide], and ME0177 [2-nitro-benzoic acid N′-(3,5-dichloro-2-hydroxy-benzylidene)-hydrazide] [58][70][141,152], were shown to inhibit the expression of T3SS genes through the inhibition of the regulator encoding gene hrpB [55][122]. All three salicylidene acylhydrazides could suppress the multiplication of R. solanacearum in planta and protect tomato from bacterial speck caused by P. syringae pv. tomato [55][122]. Since Yang et al. reported that ME0054 and ME0055 are T3SS inhibitors in E. amylovora [68][121], these findings suggest that salicylidene acylhydrazides and their derivatives are effective against different plant pathogenic bacteria.