Modern cancer therapies have achieved a remarkable improvement in overall survival and patients’ quality of life. However, cardiovascular toxicities are still a major concern. A specific Cardio-Oncology unit is key to offering patients with cancer the best approaches to treatment while minimizing adverse cardiac effects. Moreover, this area of medicine requires a large expertise and has limited trials on which to base decision-making. The development of structured Cardio-Oncology programs leads to better patient care and generates scientific evidence that may impact patient’s survival outcomes.

- Cardio-Oncology

- cardiovascular disease

- cancer

- cardiotoxicity

- program

1. Introduction

2. Organization of a Cardio-Oncology Unit

2.1. Objective of the Cardio-Oncology Unit

The aim of a Cardio-Oncology Unit is to provide specialized multidisciplinary approach and consistent, continuous, coordinated and cost-effective care during the cancer process [9]. It consists of the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of cancer patients at risk of cardiotoxicity. It also involves the monitoring and treatment of cancer patients at risk or with concomitant CV diseases. The final goal of CO services is to facilitate optimal cancer treatments and prevent the unwarranted withdrawal of treatment. Barros-Gomes et al. describe the objectives in their CO practice in the Mayo Clinic as follows: (1) to facilitate the diagnosis, monitoring and therapy of cancer treatment related cardiovascular complications; (2) to evaluate the baseline cardiovascular risks prior to cancer treatment and implement strategies for reducing the risk of developing cardiovascular complications; and (3) to assist the patient with cardiovascular care through long-term follow-up [10].2.2. Components of Cardio-Oncology Team

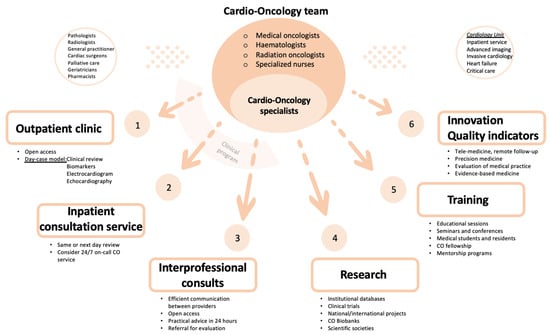

Cardio-Oncology is a discipline that involves different specialized professionals and demands direct communication between them to discuss shared patients. Therefore, a multidisciplinary team is crucial [9,11][9][11]. The nucleus of the CO team is composed of cardiologists (usually with a special interest and experience in the management of cardiac conditions in cancer patients), medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, hematologists and specialized nurses. Apart from the core members, the CO team also needs a close relationship with other professionals like family doctors, pathologists, radiologists, the palliative care team, pharmacists, cardiac surgeons, internists, etc. With regard to the cardiology team, Clinical Cardiology and Cardiology Imaging are usually the axis of the CO team, but multiple cardiology subspecialties may also be involved. They include the inpatient cardiology ward, cardiology critical care unit, invasive cardiology unit and heart failure specialists, among others.2.3. Cardio-Oncology Programs

Ideally, a Cardio-Oncology program should cover five different areas: clinical, research, training, innovation and quality indicator evaluation (Figure 1).

2.3.1. Clinical Program

The CO outpatient clinic is the main activity in a CO program. Most CO consultations should be organized as a face-to-face day-case model, which reduces the number of visits to the hospital and avoids treatment delay. The aim of a day-case model is to provide clinical assessment, non-invasive investigations (blood tests with cardiac biomarkers, electrocardiogram and echocardiography) and multidisciplinary discussion on the same day. Invasive cardiac investigations, if appropriate, can be delivered in collaboration with the cardiology department (advanced cardiac imaging and interventional procedures). The virtual outpatient clinic, using a telephone call or videoconferencing, is an option to connect with patients without in person appointment, e.g., to monitor vital signs or to share test results. A CO program can be established taking advantage of existing resources, such as a specialized nursing staff and a heart failure program, thereby patients who develop significant cardiotoxicity could be transferred to HF Unit for a more specific management [12].

2.3.2. Research Program

Cardio-Oncology is a recently created and evolving subspecialty with limited trials on which to base decision-making. Thus, a great deal of the management of the patients relies on consensus or expert opinion. One of the main goals of creating a CO program is to participate in developing high-quality scientific evidence. A CO service should collect clinical data of patients attended in the outpatient clinic. Advanced and multidisciplinary imaging and CO biobanks are also essential to build new prediction models of cardiotoxicity. In addition to focusing in a concrete area of local research and expertise, it is crucial to participate in multicentric studies and clinical trials.2.3.3. Training Program

Cardio-Oncology training should have an structured program that includes organized educational sessions with the Cardiology, Hematology and Oncology teams [14]. Like any other subspecialty, training medical students, cardiology residents and fellows in Cardio-Oncology is fundamental. It would also be worthwhile to regulate a fellowship in Cardio-Oncology and create mentorship programs for cardiologists interested in this field. This would help increase the visibility of CO and its program among other health care professionals and institutions. Establishing educational opportunities to provide additional experience in CO, like professional seminars and conferences, is also recommended for all CO team members. Education and support for patients also needs to be considered, so they can learn more about their disease and treatment [12].2.3.4. Innovation in Cardio-Oncology

Despite recent advances in Cardio-Oncology and the increase in information and evidence-based approaches in the diagnosis, management and treatment of oncological patients with cardiovascular disease, there are still many gaps in knowledge and areas of uncertainty. Collaborative groups may share information and databases that increase awareness of these kind of patients and improve outcomes. Sharing experience and knowledge may create a bigger database that will make it possible to get specific and copious information and data that can extrapolated to daily clinical practice. Artificial intelligence, patient-centered data, tele-medicine and remote follow-up are several of many fields that need to be explored and exploited in the next future. Finally, individualized medicine derived from targeted treatment in specific scenarios may lead to treatments with greater efficacy and fewer secondary effects [15].2.3.5. Quality Indicators

There is increasing interest in discovering new tools that permit a comprehensive evaluation of quality of care, including structural and process indicators and outcomes in cardiovascular disease. Geographical and social variation in medical care delivery, as well as the difficulty in the assessment of outcomes and the need to invest in closing the so called “evidence-practice gap”, has led several medical societies to try to unify and establish shared pathway goals in the management and outcomes of patients with cardiovascular disease. Currently, the use of quality indicators (QI) to evaluate medical practice is well accepted, as they may serve as a way to promote and enhance evidence-based medicine, through quality improvement, benchmarking of care providers and accountability. Specific pathways have been proposed to establish reliable QI. The most acknowledged program divides the QI development process into four steps: identifying the domain of care, constructing candidate quality indicators, selecting the final quality set and assessing feasibility [16].2.4. Pathway of Care

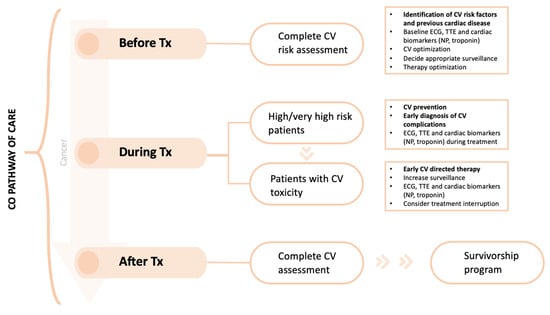

Cardio-Oncology consultations are aimed at patients at considerable risk of CV complications related to anticancer treatment. Lancellotti P et al., in a report from the ESC Cardio-Oncology Council, define high risk patients as: (1) patients receiving potentially cardiotoxic treatment; (2) patients prior to cancer surgery if they have previous CV disease or are expected to receive additional cancer treatment; (3) patients who develop CV symptoms during oncological treatment; (4) patients receiving cancer treatment who develop asymptomatic newly reduced cardiac function; (5) patients with prior childhood cancer treatment; (6) those planning pregnancy or those who develop CV symptoms during pregnancy [9]. The new Cardio-Oncology guidelines also provide tools to stratify cardiovascular toxicity risk of many cancer treatments [17]. Low-risk patients can follow regular oncology monitoring without special cardiology follow-up. The main pathway of care in CO programs is the CV assessment and management of cancer patients before, during and after the cancer therapy (Figure 2).

3. Conclusions

Cardio-Oncology now goes far beyond ventricular dysfunction screening and treatment. Cardiotoxicity comprises a wide spectrum of myocardial, pericardial, coronary and arrhythmic complications. Cardio-Oncology units should perform thorough cardiovascular management of cancer patients to enhance their quality of life, avoid unnecessary withdrawal from cancer therapies and improve their prognosis. This is a complex and challenging job that requires a multidisciplinary approach and continuous communication among all parties involved, including the patients. A comprehensive and structured program is the key to success. The Cardio-Oncology team should be patient-centered, but should also focus on research, training and innovation.References

- Koene, R.J.; Prizment, A.E.; Blaes, A.; Konety, S.H. Shared Risk Factors in Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer. Circulation 2016, 133, 1104–1114.

- Ameri, P.; Canepa, M.; Anker, M.S.; Belenkov, Y.; Bergler-Klein, J.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Farmakis, D.; López-Fernández, T.; Lainscak, M.; Pudil, R.; et al. Cancer diagnosis in patients with heart failure: Epidemiology, clinical implications and gaps in knowledge. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 879–887.

- Banke, A.; Schou, M.; Videbaek, L.; Møller, J.E.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Gustafsson, F.; Dahl, J.S.; Kober, L.; Hildebrandt, P.R.; Gislason, G.H. Incidence of cancer in patients with chronic heart failure: A long-term follow-up study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 260–266.

- Moliner, P.; Lupón, J.; de Antonio, M.; Domingo, M.; Santiago-Vacas, E.; Zamora, E.; Cediel, G.; Santesmases, J.; Díez-Quevedo, C.; Isabel, M.; et al. Trends in modes of death in heart failure over the last two decades: Less sudden death but cancer deaths on the rise. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 1259–1266.

- Nhola, L.F.; Villarraga, H.R. Fundamentos de las unidades de cardio-oncología. Rev. Española Cardiol. 2017, 70, 583–589.

- Ammon, M.; Arenja, N.; Leibundgut, G.; Buechel, R.R.; Kuster, G.M.; Kaufmann, B.A.; Pfister, O. Cardiovascular management of cancer patients with chemotherapy-associated left ventricular systolic dysfunction in real-world clinical practice. J. Card. Fail. 2013, 19, 629–634.

- Parent, S.; Pituskin, E.; Paterson, D.I. The Cardio-oncology Program: A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Care of Cancer Patients With Cardiovascular Disease. Can. J. Cardiol. 2016, 32, 847–851.

- Pareek, N.; Cevallos, J.; Moliner, P.; Shah, M.; Tan, L.L.; Chambers, V.; Baksi, A.J.; Khattar, R.S.; Sharma, R.; Rosen, S.D.; et al. Activity and outcomes of a cardio-oncology service in the United Kingdom-a five-year experience. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 1721–1731.

- Lancellotti, P.; Suter, T.M.; López-Fernández, T.; Galderisi, M.; Lyon, A.R.; Van der Meer, P.; Cohen, A.; Zamorano, J.L.; Jerusalem, G.; Moonen, M.; et al. Cardio-Oncology Services: Rationale, organization, and implementation. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 1756–1763.

- Barros-Gomes, S.; Herrmann, J.; Mulvagh, S.L.; Lerman, A.; Lin, G.; Villarraga, H.R. Rationale for setting up a cardio-oncology unit: Our experience at Mayo Clinic. Cardiooncology 2016, 2, 5.

- Arjun KGhosh Charlotte Manisty Simon Woldman Tom Crake Mark Westwood, J.M.W. Setting up cardio-oncology services. Br. J. Cardiol. 2017, 24, 1.

- Snipelisky, D.; Park, J.Y.; Lerman, A.; Mulvagh, S.; Lin, G.; Pereira, N.; Rodríguez-Porcel, M.; Villarraga, H.R.; Herrmann, J. How to Develop a Cardio-Oncology Clinic. Heart Fail. Clin. 2017, 13, 347–359.

- Okwuosa, T.M.; Barac, A. Burgeoning Cardio-Oncology Programs: Challenges and Opportunities for Early Career Cardiologists/Faculty Directors. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 1193–1197.

- Sadler, D.; Chaulagain, C.; Alvarado, B.; Cubeddu, R.; Stone, E.; Samuel, T.; Bastos, B.; Grossman, D.; Fu, C.L.; Alley, E.; et al. Practical and cost-effective model to build and sustain a cardio-oncology program. Cardiooncology 2020, 6, 9.

- Brown, S.-A.; Rhee, J.-W.; Guha, A.; Rao, V.U. Innovation in Precision Cardio-Oncology during the Coronavirus Pandemic and Into a Post-pandemic World. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 145.

- Aktaa, S.; Batra, G.; Wallentin, L.; Baigent, C.; Erlinge, D.; James, S.; Ludman, P.; Maggioni, A.P.; Price, S.; Weston, C.; et al. European Society of Cardiology methodology for the development of quality indicators for the quantification of cardiovascular care and outcomes. Eur. Heart J. Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 2022, 8, 4–13.

- Lyon, A.R.; López-Fernández, T.; Couch, L.S.; Asteggiano, R.; Aznar, M.C.; Bergler-Klein, J.; Boriani, G.; Cardinale, D.; Córdoba, R.; Cosyns, B.; et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS). Eur Heart J 2022, 43, 4229–4361.

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726.

- Zamorano, J.L.; Lancellotti, P.; Rodriguez Muñoz, D.; Aboyans, V.; Asteggiano, R.; Galderisi, M.; Habib, G.; Lenihan, D.J.; Lip, G.Y.; Lyon, A.R.; et al. 2016 ESC Position Paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: The Task Force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2768–2801.