Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Birgitta Dresp and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

When “hijacked” by compulsive behaviors that affect the reward and stress centers of the brain, functional changes in the dopamine circuitry occur as the consequence of pathological brain adaptation. As a brain correlate of mental health, dopamine has a central functional role in behavioral regulation from healthy reward-seeking to pathological adaptation to stress in response to adversity.

- dopamine

- brain

- addiction

- stress

- anhedonia

1. Introduction

The neurotransmitter dopamine fulfills a critical function in regulating the responses of the mesolimbic system, also known as the reward system, in the neural circuits of the mammalian brain [1]. The reward system governs and regulates responses ranging from pleasure and cravings to disgust and anhedonia, triggered by chemicals and other stimuli and guiding a larger proportion of our behavior than we may be aware of or are ready to admit [2]. In ancient times, the function of the reward system made the difference between life and death, because it made us and other species deploy most of our or their attention and behavioral effort towards things that were important for the survival of the species, such as food, sleep, and sex. Our ancestors did not have a supermarket around the corner but had to hunt for food and often had to deploy a considerable amount of time and energy to find it. An individual who found sweet fruit in the environment, for example, had better consume it quickly, in as large of quantities as possible, before another did. Ripe fruits have the highest sugar content and provide higher amounts of instant energy compared with other foods. The human preference for sweet nutrients may, indeed, be due to the evolutionary advantage that craving and eating high-calorie foods has caused. Responding selectively to survival-relevant stimuli, in the course of evolution, has become hardwired into the brain’s reward system [3]. Food, sleep, physical contact, and sex are primary stimuli that reinforce the neural connections of the reward system, and a craving for these primary stimuli is inherent in humans [4], as well as most other mammals [5]. The reward system is composed of brain structures that mediate the physiological and cognitive aspects of a reward. This involves neurobiological processes driving the brain’s capapcity to associate stimuli such as substances or activities with a pleasant and positive outcome. Reward-associated mechanisms explain why individuals search for initially positive stimuli again and again and why this can ultimately lead to compulsive behaviors and addicions that pose a threat to mental health. Pandemic-related adversities and the stresses they engendered [6], with the long lockdown periods where people in social isolation had to rely on food for comfort or digital tools to get feedback rewards via the internet, can be seen as major triggers of changes in motivation and compulsive reward-seeking behaviors worldwide. These are linked here to the pathological adaptation of dopamine-mediated reward circuitry, triggered and consolidated through functional links with brain structures controlling the circadian rythm and/or the responses to chronic stress. This offersplausible insight into why environmental adversity pushed individuals of all nations, during and after the pandemic, into compulsive behaviors that couldlead to sleep disorders, anhedonia (from the Greek language: “inability to feel or experience pleasure”), depression, and in extreme cases, suicidal ideation.

2. COVID-19 Pandemic and Mental Health

In 2022, the World Health Organisation (WHO) issued a brief [7][89] with facts and figures showing that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a severe impact on the mental health and well-being of people around the world. While many individuals have adapted, others have experienced mental health problems that, only in some cases, are a consequence of COVID-19 infection. The brief stated further that the pandemic also continues to impede access to mental health services and raised concerns about increases in suicidal behavior, stressing the causal role of psychological and environmental factors producing ontological insecurity in individuals and populations. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, experts havewitnessed a- ➢

-

significant rise in addictions and related mental illnesses;

- ➢

-

significant rise in the corresponding anti-depressant prescription uptake;

- ➢

-

increased risk of suicidal ideation or suicide.

2.1. Adversity and Vulnerability

Mental health issues arise from a specific context. Recently reported effects of the pandemic have shown, beyond all reasonable doubt, that adversity affects people’s capacity tocope with the stresses it produces. Conditions of extreme adversity challenge the stress and immune system responses needed for coping, and beyond a certain threshold, such conditions can trigger behavioral changes as listed and discussed here above; all of them have been functionally linked to the complex brain pathways involving dopamine release, reward mechanisms, and their interactions or regulations [19][20][77,79]. During the different waves of the pandemic, many individuals had an actual COVID-19 infection, with direct effects on the brain’s immune system, stress centers, and the dopamine system, affecting people’s mood beyond the actual duration of the illness. Cohort studies examining the psychopathological and cognitive status of COVID-19 pneumonia survivors [21][101], for example, have shown that three months after discharge from the hospital, close to 40% still self-rated their symptoms in the clinical range for at least one psychopathological dimension, with persistent depressive symptomatology, while anxiety and insomnia progressively decreased during follow-up. Studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on individuals with eating disorders have been performed all over the world, showing that the traumatic effects of COVID-19 have exacerbated specific eating disorder-related psychopathologies [22][102], pointing towards complex interactions between environmental and personal factors. Healthy siblings of patients with eating disorders have beenfound to present specific psychological vulnerabilities, i.e., specific associations between interpersonal sensitivity and posttraumatic symptoms, including anxiety, depression, and compulsive behaviors [22][23][102,103]. Moreover, having to cope with adversity during childhood increases the risk of mental health problems in adulthood, and it has been suggested that this effect may be mediated by increased striatal dopamine neurotransmission [24][104]. Also, while resilience may be viewed as an individual’s positive adaptation to experiences of adversity [25][105], it is also known that conditions of adversity reinforce the already exisiting vulnerability to mental illness and may create a new vulnerabilty duringspecific adverse contexts such as a pandemic [10][92] or armed conflict [26][106]. It has been confirmed that stress responses can cause functional changes in the amygdala and the dopaminergic circuits of the brain in relation to stress-induced cortisol release mechanisms [26][27][28][106,107,108]. Some of these studies have shown a cortisol-induced increase in serotonin in subjects with major depressive disorder, offering further insight into the functional links between stress, sleep disorders, and depression, where an increase in one brain correlate affects another, thereby creating or increasing the physiological vulnerability to mental illness in individuals under prolonged stress.2.2. Bingeing

The COVID-19 pandemic creatednegative health consequences such as consuming high-fat and sugar foods, increasing body weight [29][109], anxiety and depression [30][110], anhedonia [30][31][110,111], or a combination thereof [32][83]. As a core characteristic of eating disorders and all forms of addiction [33][22], bingeing is associated with changes in the activity of the brain’s reward system in the process of pathological adaptation of the central nervous system through deregulation of the reward mechanisms generating positive reinforcement. As explained earlier, this deregulation progressively leads to the consolidation of the anti-reward brain state that produces anxiety, anhedonia, and depression. Most people during COVID-19 lockdown reportedly turned to substances or other “rewarding” activities to deal with the stress of isolation and the negative feelings it engendered [34][35][112,113]. A number of factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic may have contributed to the reportedly high incidence of food addictions during and after that period [35][36][113,114]. It has been suggested that people under the influence of the excessive and uncontrolled consumption of extremely palatable foods experience similar highreward sensations as recorded for addicts resorting to classic intoxicants, both at the behavioral and neurobiological levels [35][36][37][88,113,114]. As lives and daily routines were transformed by the pandemic and rapidly rising anxiety fueled by social isolation and, often, unemployment, the mental health of millions is at stake. In the United States alone [38][115], close to 60% of adults screened declared that the pandemic led them to abuse alcohol and other drugs, binge eating, and/or compulsive internet gambling.2.3. The New Digital Drug

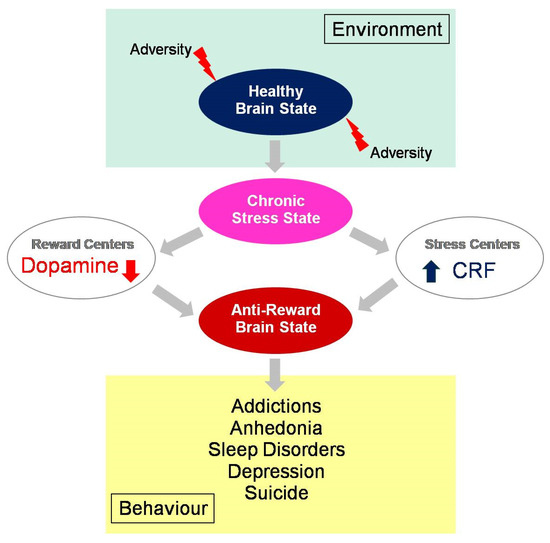

COVID-19 spread across the world ata rapid pace, and to further limit the spread of infection, lockdowns were declared in most parts of the world. People were forced to stay indoors, and the internet was the only source of entertainment. This context engendered addictive behavior with measurable negative effects on anxiety and sleep quality, especially among younger individuals [38][39][40][41][115,116,117,118]. Digital addiction involves theinternet as a channel through which individuals may access whatever content they want (games, social media, shopping, etc.) wherever and whenever they want. The development of the addictive response is digitally facilitated by such instant availability [40][41][42][43][44][45][117,118,119,120,121,122]. At an advanced stage, digital addiction [41][118] is associated with significant and permanent symptomatic psychological, cognitive, and physiological states, with a measurable dopamine deficiency and impaired mental health [44][121]. Psychological stress [44][45][46][47][121,122,123,124], anxiety and depression [48][49][50][125,126,127], eating disorders [51][52][53][128,129,130], sleeplessness [54][55][131,132], and mood changes, along with suicidal ideation [56][57][133,134], are the most frequently reported. A compilation of cross-national studies on more than 89,000 participants from 31 nations performed almost ten years ago, well before the COVID-19 pandemic, already suggested a global prevalence estimate for digital addiction of 6% worldwide [43][120]. Interdependent variables such as sociocultural factors, biological vulnerabilities (genetic predisposition and preexisting metabolic disorders), and psychological factors (personality characteristics and a negative affect) play a critical role [58][59][60][61][62][63][135,136,137,138,139,140]. Excessive seeking of the new digital drug and addiction to the internet have been identified as part of the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, with a major impact on the mental health of predominantly young people and teenagers [61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146]. This involves, like all compulsive behavior loops, the brain’s reward circuitry, with all the complex interactions between environmental, metabolic, and neurobiological changes in the brain discussed above. Dopamine, and the modulation thereof under conditions of adversity and stress (Figure 1), is the common functional denominator [70][147]. Figure 1. Behavioral consequences of an anti-reward brain state, with ultimately depleted dopamine levels in the reward centersand increased cortisol levels in the centers that regulate the brain’s response in pathological adaptation to chronic stress. Under adverse environmental conditions, such as those generated by the COVID-19 pandemic, healthy reward-seeking has progressively evolved into stress-related compulsory behaviors and/or addictions leading to anhedonia and related mental health issues worldwide.

Figure 1. Behavioral consequences of an anti-reward brain state, with ultimately depleted dopamine levels in the reward centersand increased cortisol levels in the centers that regulate the brain’s response in pathological adaptation to chronic stress. Under adverse environmental conditions, such as those generated by the COVID-19 pandemic, healthy reward-seeking has progressively evolved into stress-related compulsory behaviors and/or addictions leading to anhedonia and related mental health issues worldwide.