Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Natalia NP Paroul.

Esta pesquisa investiga as distinções entre canela verdadeira e falsa. Dadas as complexas composições dos óleos essenciais (OE), foram exploradas várias abordagens de discriminação para garantir a qualidade, segurança e autenticidade, estabelecendo assim a confiança do consumidor.

Given the intricate compositions of essential oils (EOs), various discrimination approaches were explored to ensure quality, safety, and authenticity, thereby establishing consumer confidence.

- discrimination

- physical–chemical analysis

- instrumental analysis

- food industry

1. Introduçãctio

Os óleos e

n

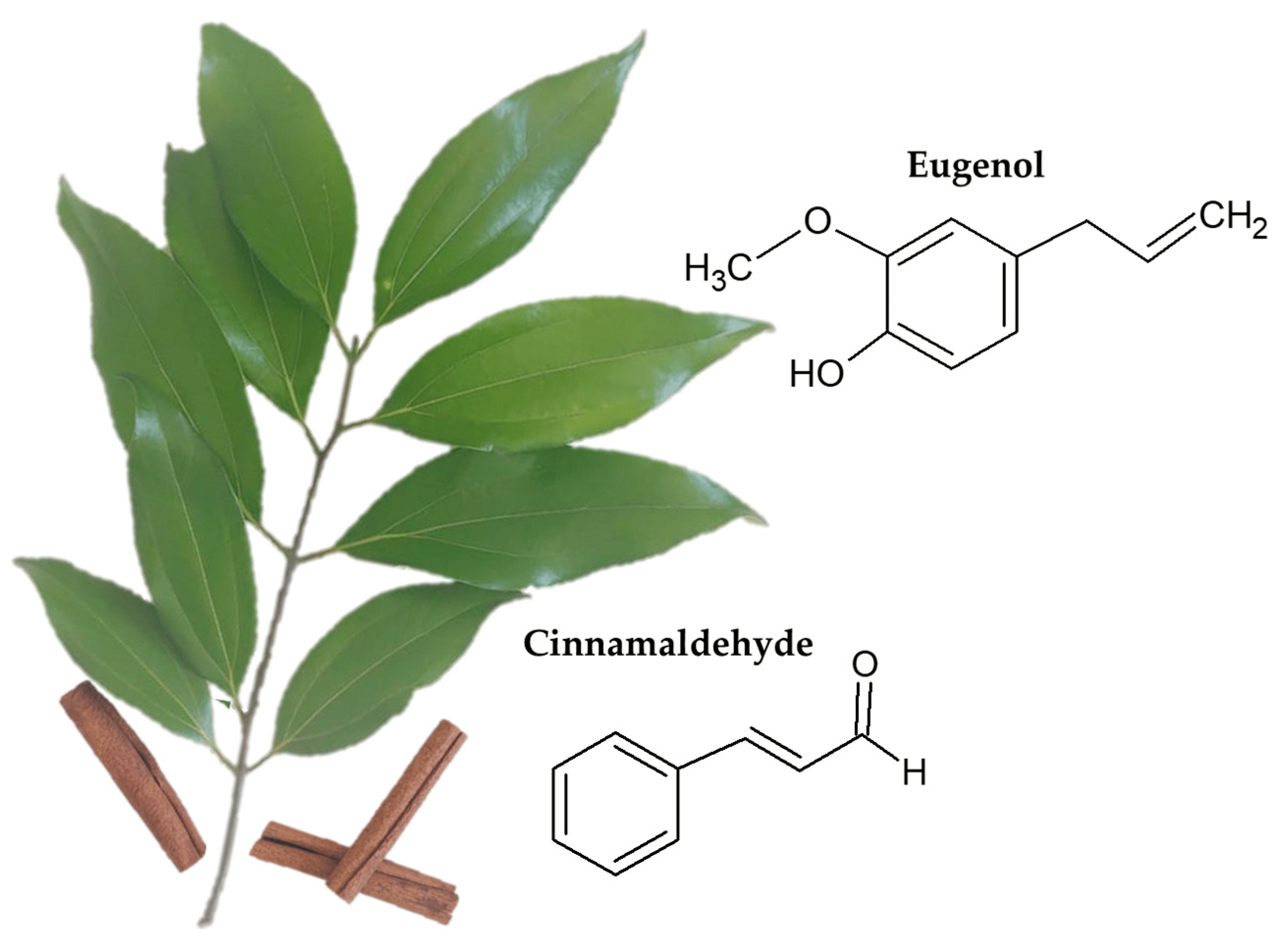

Essenctiais (OE) são produtosl oils (EOs) are naturais obtidos de diferentes partes dasl products obtained from different parts of plantas (raízes, cascas, folhas e flores). São líquidos hidrofóbicos (roots, bark, leaves, and flowers). They are hydrophobic liquids contendo misturasaining complexas de compostos aromático mixtures of aromatic compounds derivados da biossíntese deed from the biosynthesis of secondary metabólitos secundárioolites, servindo como defesa contra agentesg as a defense against externos. Osal agents. The componentes dos OE pertencem a dis of EOs belong to differentes classes deof compostos, comounds, such as monoterpenos ees and sesquiterpenos, álcoois, ésterees, alcohols, esters, aldeídos, cetonas e fenóis, todos possuindo várias propriedadehydes, ketones, and phenols, all of which possess various biológicaogical properties [1 ] [1]. AtCualmente, os OEs têm sido amplamente utilizados nas indústrias alimentíciarrently, EOs have been widely used in the food, cosmética, farmacêutica e química, bem como naetics, pharmaceutical, and chemical industries, as well as in perfumariaery [[2]. One 2of ].Umthe doshighly óleosvalued essenciais (OE) muito valorizados pela indústria alimentícia é o óleo essencial de canelatial oils (EOs) by the food industry is cinnamon essential oil (CEO) do gênerofrom the Cinnamomum genus, que pode serwhich can be extraído da raiz, da casca ou das folhas, cada um acted from the root, bark, or leaves, each presentando composições químicas distintaing distinct chemical compositions. Notavelmente, o óleobly, cinnamon bark essencial de casca de canelatial oil (EO) é rico em cinis rich in cinnamaldeído, o OE da folha contémhyde, leaf EO contains eugenol e o OE da raiz contém cânfora, and root EO contains camphor [[3]. 3CEO ].has Foi demonstrado que o CEO possuibeen shown to possess antimicrobianol [ 4 [4][5], 5 ], antifúngicoungal [ 6 [6][7][8], 7 , 8 ], anti-inflamatóriomatory [ 9 [9][10], 10 ] eand antioxidante [[11][12] 11 , 12] Aactivitidades. Consequentemente, o CEO encontra aplicações emly, CEO finds applications in culinary preparações culinárias devido ao seutions due to its sweet and spicy aroma e sabor doce e picante. É comumente usado em temperos de carne, assados e doces como conservanteand flavor. It is commonly used in meat seasoning, baked goods, and pastries as an alternativo [e preservative 13[13], ]and e em gomas de mascar como agentein chewing gum as a flavoring agent [14].

Cinnarmomatizante [ 14 ].

A n can bela pode ser encontrada no mercado em duas espécies principais found on the market in two main species: Cinnamomum verum (cantruela verdadeira ou cinnamon or canCela do Ceilãylon cinnamo n) eand Cinnamomum cassia (siyn. Cinnamomum Aaromaticum) ., falsae canela). Devido ao seu alto valor de mercado, sabor mais doce e suave e maiores quantidades de compostos fenólicos e aromáticos, como innamon). Due to its high market value, sweeter and milder flavor, and higher amounts of phenolic and aromatic compounds such as eugenol e cinand cinnamaldeído, a canela verdadeira é mais difícil de obter em hyde, true cinnamon is more challenging to obtain comparação com a canela falsa. A falsa canela tem sabor mais aded to false cinnamon. False cinnamon has a more astringente e contém maio taste and contains a higher concentração de ction of coumarina em sua in its composição. O consumo de grandes quantidades de cition. Consuming large amounts of coumarina pode acarretar efeitos can lead to adversos à saúde, e health effects, thus justificando assim o seu menor custo no mercado. Comoying its lower cost in the market. As a resultado, a canela verdadeira é suscetível a, true cinnamon is susceptible to fraudes devido à sua due to its qualidade e alto valor, e a canela falsa é frequentemente usada comoty and high value, and false cinnamon is often used as a substituto e/oue and/or adulterante, tanto na forma , both in powdered form and as a CEO.

In detail, pó quanto como CEO.

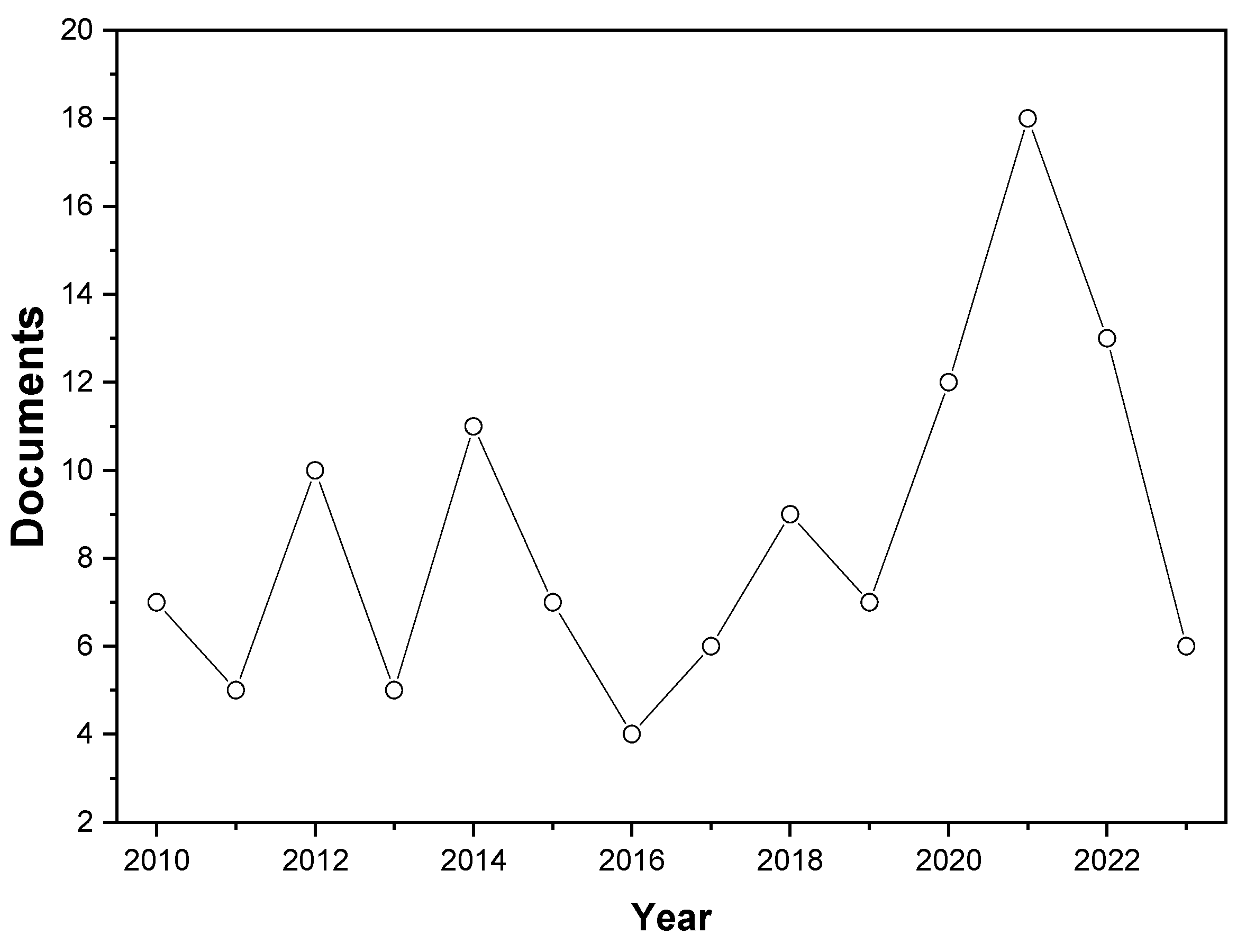

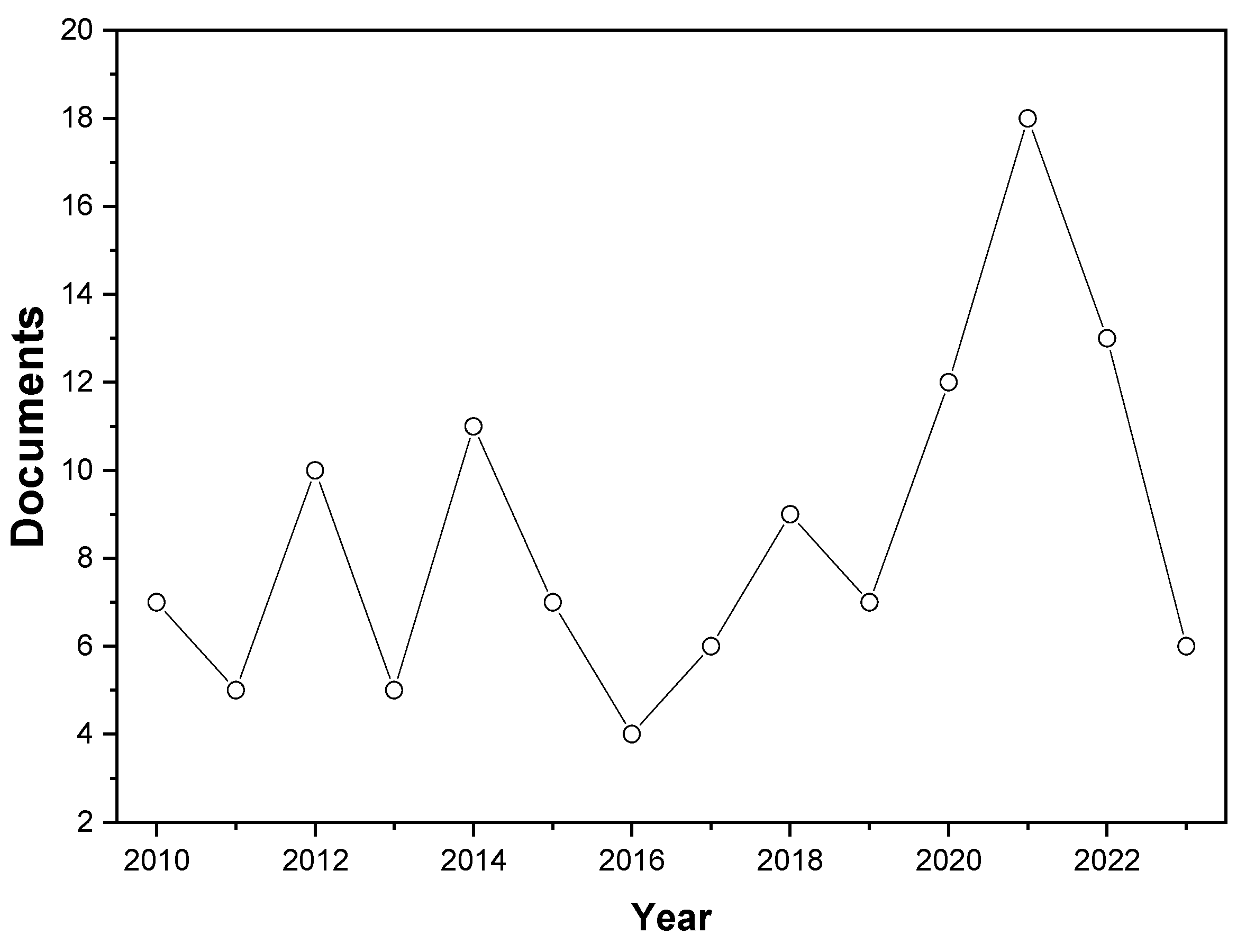

Ain just over the last thirteen years, cinnamon has received sigarantia da qualidade, segurançnificant attention by the scientific community. The search employed specific terms, including “true and false cinnamon”, “Cinnamomum verum and eCinnamomum cassia”, “authenticidade dos OEs é uma preocupação primordial devido às suas composições complexas. Os OE, derivados de várty of cinnamon essential oil”, or “cinnamon adulteration”, and focused on articles where these terms appeared in the field title, abstract, and keywords. The intention was to exclude publications unrelated to the subject matter. The search encompassed the entire period from the inception of the Scopus database up to 2010, with the final retrieval conducted in September 2023. Figure 1 illustras partes de plantas, abrangem uma gama diversificada de compostostes the upward trajectory of scientific publications related to cinnamon over time. This is evidenced by a total of 120 scientific papers published in recent years.

The assuromáticos, cada um contribuindo para os seus aromas distintos e potenciais propriedades terapêuticas. À medida que estes óleos chegam aance of quality, safety, and authenticity of EOs is a paramount concern due to their intricate compositions. EOs, derived from various plant parts, encompass a diverse array of aromatic compounds, each contributing to their distinct aromas and potential therapeutic properties. As these oils find their way into numerososus produtos em indústrias que vão desde a alimentar e cosmética até à farmacêutica, garantir a sua pureza e cts in industries ranging from food and cosmetics to pharmaceuticals, ensuring their purity and legitimidade torna-seacy becomes imperativo para salvaguardar o bem-e to safeguard consumer well-being.

A plestar do consumidor.

The assuromáticos, cada um contribuindo para os seus aromas distintos e potenciais propriedades terapêuticas. À medida que estes óleos chegam aance of quality, safety, and authenticity of EOs is a paramount concern due to their intricate compositions. EOs, derived from various plant parts, encompass a diverse array of aromatic compounds, each contributing to their distinct aromas and potential therapeutic properties. As these oils find their way into numerososus produtos em indústrias que vão desde a alimentar e cosmética até à farmacêutica, garantir a sua pureza e cts in industries ranging from food and cosmetics to pharmaceuticals, ensuring their purity and legitimidade torna-seacy becomes imperativo para salvaguardar o bem-e to safeguard consumer well-being.

A plestar do consumidor.

Figure 1. Number of annual peer-reviewed publications related to cinnamon.

Umahora of techniques infinidhade de técnicas foi detalhada na literatura científica para abordar a naturezave been detailed in the scientific literature to address the multifacetada dos OE. Essas meted nature of EOs. These methodologias abrangem um ees span a spectro desde avaliaçõesum from traditional organolépticas tradicionais, que eeptic assessments, which involvem avaliações human sensoriais humanas, até métodos analíticos mais avançados e y evaluations, to more advanced and precisos. As abordagens físicas, químicas ee analytical methods. Physical, chemical, and instrumentais desempenham papéis fundamentais nal approaches play pivotal roles in verificação daying the genuinidade dosneness of CEOs.

Técnicas es

Spectroscóopicas, como espectroscopia de techniques, such as infravermelho e ressonância magnética nuclear, fornecem informações sobre a estrutura molecular dos OEs, auxiliando na suared and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, provide insights into the molecular structure of EOs, aiding in their identificação e auttion and authenticação. Métodos ction. Chromatográficos, como caphic methods, such as gas chromatografia gasosa-ephy-mass spectrometria de massa y (GC-MS) e cromatografia líquida de alta eficiência and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), permitem a enable the separação etion and quantificação de compostostion of individuais dentro das matrizesl compounds within the complexas de EO. Estas técnica EO matrices. These techniques servem como ferramentas valiosas para identificar marcadores específicos que podem d as valuable tools for pinpointing specific markers that can distinguir CEOs autênticos de versõessh authentic CEOs from adulteradas ou falsificadated or counterfeit versions.

No eventanto, a aplicação bem sucedida destas técnicas exige pessoal qualificado, equipamento ertheless, the successful application of these techniques demands skilled personnel, extensivo e um investimento de tempoe equipment, and a considerável. Além disso, algumas abordagens podem alterarable time investment. Moreover, some approaches may inadvertidamente a amostra do CEO ou exigem muitos recursos, colocando desafios à sua utilização generalizadaently alter the CEO sample or are resource-intensive, posing challenges to their widespread use.

2. Cinnamomum sp.

A cCinnanela é uma especiaria pertencente ao gêneromon is a spice belonging to the genus Cinnamomum dain famíliathe Lauraceae e é amplamente utilizada em váriafamily, and it is widely used across various culturas ao redor do mundo [es around the 15world ][15]. OThe nome “canela” éame “cinnamon” is derivado da palavra grega, que significa “madeira doceed from the Greek word, meaning “sweet wood” [[16]. 16It ]. Éis uma árvore perene que pode atingir alturas de 7 aa perennial tree that can grow to heights of 7 to 10 m, embora também possa seralthough it can also be cultivada como arbusto, podendo atingir menos de 3 m de altura. A canela prospera emted as a shrub, reaching less than 3 m in height. Cinnamon thrives in tropical, warm, and humid climas tropicais, quentes e úmidos e fica pronta para a colheita após cerca de três anos de crescimento. Possui folhas verde-escuras, pequenas flores branco-amareladas e frutos roxos que contêm uma única sementetes, and it becomes ready for harvest after about three years of growth. It features dark green leaves, small white-yellowish flowers, and purple fruits that contain a single seed [ 3 ][3]. CeArca de 250 a 350 espécies de canela foramound 250 to 350 species of cinnamon have been identificadas e ed and distribuídas na América do Norte, Américated across North America, Central, América do Sul, Sudeste Asiático e America, South America, Southeast Asia, and Austrália. Dentre essas espéalia. Among these species, quatro são four are consideradas de maioed of greater importância e são comumente utilizadas para obtenção da especiariaance and are commonly used for obtaining the spice: Cinnamomum zeylanicum Blume (também conhecidalso known as como C. verum ), Cinnamomum Aaromaticum (our C. cassia ), nativa dae to China, Cinnamomum burmannii , nativa dae to Indonésia eesia, and Cinnamomum loureiroi , nativo de to Vietnãam [ 17 , 18 ][17][18]. SeuIts consumo estáption is associado ated with health benefícios à saúde, como atividadeits such as antimicrobianal activity [ 19 ][19], propriedades antioxidante properties [ 20 ][20], efeitos anticancerígeno effects [[21], 21and ] glucose controle da glicose no in diabetes [ 22 ][22]. A cCinnanela émon is utilizada em alimentos, temperoed in foods, seasonings, cosméticos eetics, and medicamentos, e está disponível em diversations, and is available in various formas, como integral, moídas, such as whole material, ground, extratos ou óleos essenciais obtidos das folhas e cascas. No entanto, octs, or essential oils obtained from the leaves and bark. However, the consumo de canela também pode causar efeitosption of cinnamon may also lead to adversos à saúdee health effects. O tTrans -cinnamaldeído, também conhecido como cihyde, also known as cinnamaldeído, principalhyde, the main componente da casca da canela, pode of cinnamon bark, can resultar em in skin sensibilização da pele e causartization and cause contact dermatiteis de[23]. coCinntato [ 23 ]. O áamic acido cinâmico também é conhecido por induzir hiis also known to induce hypersensibilidade aotivity upon contatoct [24 ][24]. ATrue canela verdadeira nativa dinnamon native to Sri Lanka, também conhecidaalso known as como canCeyla do Ceilãon cinnamo n, inclui ades espéthe species C. verum eand C. zeylanicum , e a canela falsa, que tem origens diversas como and false cinnamon, which have diverse origins such as China, América do Sul e Indonésia, eSouth America, and Indonesia, and inclui a espéciede the species C. cassia , C. aromáatico um, C. burmannii, eand C. loureiroi [[25] 25 ] ( Tablela 1 ). OThe aroma e o sabor da canela verdadeira são suaves e doces, e sua cor é marrom claro, enquanto a canela falsa é mais escura, além de possuir sabor mais forte, adand taste of true cinnamon are soft and sweet, and its color is light brown, whereas fake cinnamon is darker, in addition to having a stronger, astringente e picante, and spicy flavor [26 ] [26]. AlémIn disso, possuem caddition, they have distinct characterísticas distintas quanto à istics regarding the composição deition of phenolic compostos fenólicos, sendo a canela verdadeira rica em compostos aromáticos e fenólicos, como cinunds, with true cinnamon being rich in aromatic and phenolic compounds, such as cinnamaldeído ehyde and eugenol, enquanto a canela falsa possui maiores quantidades de cwhile false cinnamon has higher amounts of coumarina (2.000 a 5. (2000 to 5000 mg/kg), approximadamente um mil vezes superiores aos encontrados na canela verdadeira (2 a 5 mg / kg) e taninos na casca, o que explica o sabor adtely a thousand times higher than those found in true cinnamon (2 to 5 mg/kg), and tannins in the bark, which explains the astringent taste [ 25 , 27 , 28 , 29 ][25][27][28][29].Tablela 1. Differenças entre as espéciesces between Cinnamomum verum, eand Cinnamomum cassia species.

| C. verdadeiroum | C. cáassia | C. burmannii | C. loureiroi | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PaísCountry de origemwhere it originates | Sri Lanka | China | Indonéesia | Vietnãam |

| SFlabvor | Mild Suave Docweet | PBicante amargotter Spicy | ASpimentadocy | DocSwee picantet spicy |

| Color | CasLightanho avermelhado cla reddish brown | CDastanho avermelhado escurk reddish brown | CDastanho avermelhado escurk reddish brown | CDastanho avermelhado escurk reddish brown |

| Conteúdo de cumarina content (g/kg) | 0,.017 | 0,.31 | 2.15 | 6,.97 |

Figurae 12. Partes da canela e seus principaisof cinnamon and its main constituinteents.

2.1. ÓleCinnamon Essencial de Canetial Oila

CEOs are complex mixtures of aromatic products from the secondary metabolism of plants, normally produced by secretory cells or groups of cells from different parts of the plant, such as stems, roots, leaves, flowers, and fruits [38,39][38][39]. The essential oil content may vary according to the species, physical form of the sample, part of the plant used (Table 2), geographical origin, and stage of development of the plant [3]. The constituents of CEOs can belong to several classes of compounds, with emphasis on terpenes and phenylpropenes, which are the classes of compounds commonly found. Monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes are the most frequently found terpenes in EOs, as well as diterpenes, and minor constituents [40]. Different parts of cinnamon, bark, leaves, branches, fruits, and roots can be used for the production of essential oils by distillation and oleoresins by solvent extraction [41]. The volatile components of the EO are present in all parts of the plant (Table 2) and can be classified into monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and phenylpropenes, with main constituents such as trans-cinnamaldehyde (bark), eugenol (leaves), and camphor (root) [3,42][3][42].Table 2. Volatile compounds present in the bark and leaf of C. verum and C. cassia essential oils.

| Compounds | Content (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bark | Leaf | |||

| C. cassia | C. verum | C. verum | C. cassia | |

| 1,3-dimethyl-benzene | 0.23 | 0.15 | - | - |

| Styrene | 0.19 | 0.14 | - | - |

| Benzaldehyde | 0.41 | 0.29 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| Camphene | 0.35 | 0.21 | - | - |

| Acetophenone | 0.96 | tr | - | - |

| β-Pinene | 0.15 | 0.44 | - | - |

| Linalool | 0.68 | - | - | - |

| Camphor | 0.97 | 0.53 | - | - |

| Benzene propanal | 0.64 | 0.53 | - | - |

| Borneol | 0.19 | 0.12 | - | - |

Table 3. Biological, insecticidal, and antidiabetic activity of cinnamomum.

| Cinnamomum Species/Type |

Sample | Biological Activity | Result | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insecticidal activity | ||||||||

| C. verum | Essential oil | Odontotermes assamensis | 2.5 mg/g | [59][57] | ||||

| C. osmophloeum | Essential oil | Aedes albopictus | 40.8 µg/mL | [60][58] | ||||

| Culex quinquefasciatus | 31.6 µg/mL | |||||||

| A rmigeres subalbatus | 22.1 µg/mL | |||||||

| C. zeylanicum L. | Essential oil | Acanthoscelides obtectus | 46.8 µL/kg | [61][59] | ||||

| C. cassia | Bark extract | Tribolium castaneum | 3.96 µg/adult | [62][60] | ||||

| Lasioderma serricorne | 23.89 µg/adult | |||||||

| Antioxidant activity | ||||||||

| - | Cinnamon powder (raw extract) | ABTS | 1.52 mg/mL | [63][61] | ||||

| Cis-cinnamaldehyde | 1.95 | 2.29 | - | - | ||||

| Trans-cinnamaldehyde | ||||||||

| Cinnamon powder (in vitro digestion) | 1.18 mg/mL | 77.21 | 74.49 | 16.25 | 30.65 | |||

| Eugenol | ||||||||

| C. cassia | Extract | DPPH | 10 mg/mL | [64][62] | 0.21 | 7.29 | 79.75 | - |

| Geranyl acetate | 0.14 | 0.12 | - | - | ||||

| Benzene,1-(1,5-dimethyl-4-hexenyl)-4-methyl | 0.37 | 0.15 | - | - | ||||

| Cinnamyl acetate | 0.14 | 0.49 | - | - | ||||

| α-muuroleno | 0.47 | 0.11 | - | - | ||||

| 3-Methoxy-1,2-propanediol | - | - | - | 29.30 | ||||

| Cinnamyl alcohol | - | - | 0.07 | 0.65 | ||||

| Acetaldehyde | - | - | - | 0.47 | ||||

| o-Methoxy cinnamaldehyde | - | - | - | 25.39 | ||||

| Coumarin | - | - | 0.05 | 6.36 | ||||

| C. burmannii | ||||

| Essential oil (leave) | ||||

| DPPH | ||||

| 100 µg/mL | ||||

| [ | ||||

| 65 | ||||

| ] | ||||

| [ | 63 | ] | ||

| C. cassia | Cinnamon bark oil | DPPH O2 |

10 mg/mL 1 mg/mL |

[64][62] |

| C. zeylanicum | Essential oil (leave) | DPPH | 4.78 μg/mL | [66][64] |

| ABTS | 5.21 μg/mL | |||

| C. zeylanicum | Extract | ABTS | 1119.9 µmol Trolox/g MS | [67][65] |

| PCL | 177.4 µmol Trolox/g MS | |||

| CV | 39.8 µmol Trolox/g MS | |||

| Anti-inflammatory activity | ||||

| C. osmophloeum | Essential oil (leave) | NO production in RAW 264.7 cells | 9.7 to 65.8 µg/mL | [68][66] |

| C. cassia | Extract | NO production in RAW 264.7 cells | 9.3 to 43 µg/mL | |

| Antidiabetic effect | ||||

| - | Gelatin capsule with cinnamon powder | Group A: placebo in capsule | 17.4% reduction after 12 weeks | [69][67] |

| Group B: 1000 mg/day of cinnamon powder in capsule form | 10.12% reduction after 6 weeks | |||

| - | Cinnamon extract | Rats divided into 5 groups (I—placebo only, II to V extract concentrations) | The highest dose of 200 mg/kg was more effective | [70][68] |

| - | Cinnamon Polyphenols | Mice divided into 5 groups (diabetic model, dimethylbiguanide, low, moderate and high dose of polyphenols) | Treatments with different doses of polyphenols (0.3, 0.6 and 1.2 g/kg/d caused a marked reduction in glucose | [71][69] |

| C. osmophloeum | Essential oil (leave) | Mice were induced with diabetes and then divided into six groups receiving different concentrations of essential oil | All doses tested significantly reduced blood glucose | [72][70] |

| Antimicrobial activity | ||||

| C. verum | Essential oil | Staphylococcus hyicus | minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) values ranging from 0.078 to 0.313% | [73][71] |

| C. verum | Essential oil | Streptococcus suis Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae |

MIC and MBC ranging from 0.01 to 0.156% (v/v) | [74][72] |

| C. verum | Essential oil | Candida tropicalis | MIC of 7.8 µL/mL | [75][73] |

| C. cassia | Essential oil | Candida albicans | 65 μg/mL | [76][74] |

| C. cassia | Essential oil | Staphylococcus aureus | 1.25% MIC | [77][75] |

| C. cassia | Essential oil | Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Streptococcus pyogenes | 0.25 to 0.50 mg/mL MIC | [78][76] |

| C. cassia | Essential oil | Aspergillus flavus, Penicillium viridicatum, and Aspergillus carbonarius. | 1.67 to 5.0 µL/mL MIC | [79][77] |

2.2. Adulteration of Cinnamon Essential Oils (CEOs)

With the growth in demand in the food, perfumery, and cosmetics industries, the market for natural aromatic raw materials is expanding exponentially to meet your needs. To meet this search for aromatic products, research has focused on compounds from biotechnological processes used in the production of aromas and fragrances from other plant origins [80][78]. Intentionally altered products with hidden properties or quality and incomplete and unreliable information define adulteration. In general, counterfeiting involves actions that deteriorate the specific properties of the products while maintaining their characteristic indicators, such as appearance, color, consistency, and aroma [81][79]. Currently, the authenticity of food and food ingredients is a major challenge, as it is often related to fraud. Food adulterations have been occurring for a long time, with the difference that they have been improved over the years, accompanying or even advancing in the field of research into new methods. A greater number of adulterations among raw materials are found in spices, edible oils, honey, milk and its derivatives, fruits and fruit juice, coffee, flour, and meat products [26]. Among the raw materials, cinnamon is one of the spices commonly adulterated. These adulterations can include species (mixing different species of Cinnamomum), origin (incorrectly labeling the country of origin), additives and fillers (adding other substances such as starch, sawdust, or other spices), and oil (adulterating EOs derived from cinnamon with synthetic or cheaper oils). Due to its high added value and high cost, true cinnamon is highly prone to adulteration with false cinnamon species, which are of lower quality and cheaper, causing potential health risks and making the product unsafe for the consumer. This practice is usually carried out in powder form, which makes it difficult to discriminate between cinnamons as their characteristics are lost during the process [29]. Furthermore, true cinnamon can be adulterated with other types of spices, such as clove and chili powder, and clove and cinnamon oil, as reported by Gopu et al. [82][80]. Cinnamon fraud triggered research for the development of new, more accurate, reliable, and sensitive analytical methods in order to identify and quantify potential adulterants in true cinnamon more quickly and efficiently, ensuring food safety. Among the methods developed, chromatography is based on the determination of the main active compounds of cinnamon or adulterants, called marker compounds, such as cinnamaldehyde, eugenol, linalool, and coumarin, among others [82][80]. Cinnamon adulterations do not only occur in the form of powder, frauds are also found in CEO by mixing other compounds or even false cinnamon species. Through physical–chemical and instrumental analyses, the CEOs purity can be proven through qualitative and quantitative analyses, that is, determining the constituents or identifying the compounds present in the oil, respectively [81][79]. To prevent the entrance of adulterated cinnamon products into local markets, the regulatory sector takes several steps: product testing and certification are performed by implementing regular product testing to verify the authenticity and quality of cinnamon products; certifying authentic products with recognized standards can help consumers identify genuine products; labeling regulations require accurate information about the species, country of origin, and any additives or fillers in the product; clear and transparent labeling helps consumers make informed choices; traceability systems that track the supply chain of cinnamon products from production to market, which can help identify and eliminate adulterated products at different stages; import controls and inspections to ensure that products entering the country meet regulatory standards, which includes checking for proper documentation and compliance with labeling regulations; public awareness and education about the different types of cinnamon and their characteristics—informed consumers are less likely to purchase adulterated products; penalties and enforcement for those found guilty of adulteration, and rigorous enforcement of these penalties, which can act as a deterrent to unethical practices; collaboration with industry and associations to establish self-regulation practices and codes of conduct that promote authenticity and quality; and international cooperation with international regulatory bodies and other countries to share information and best practices in combating cinnamon adulteration, especially when products are imported. For the regulation of EOs, the molecules must come from the raw material of the reference plant to be considered and labeled as 100% pure and natural [80][78]. Adulteration of CEOs can be divided into four types [81][79]: essential oil diluted with a solvent that has similar physicochemical characteristics, such as vegetable oils or organic solvents; cheaper CEO, but similar in origin or chemical composition, mixed with authentic CEO; unique natural or synthetic compounds added to mimic aromatic characteristics or composition; and/or substituting with low-value or blending CEOs. As they are complex matrices, the EOs need to be analyzed by different techniques to ensure quality, safety, and authenticity, in addition to ensuring safety for consumers. As a result, a wide range of techniques have been reported, including organoleptic, physical, and chemical methods. However, these techniques, for the most part, require specialized people, have a high investment cost, are time-consuming, and some degrade the samples [81,83][79][81]. Molecules produced from natural reagents, also known as semi-synthetic compounds, can be used to adulterate specific EOs [80][78]. Cinnamaldehyde molecules can be produced from the benzaldehyde found in bitter almonds and used as an adulterant [84][82]. There are several scams associated with bitter almond and CEO, and since the false origin is cheaper than the Ceylon origin, blends between these CEOs are common. Despite this, it is possible to detect this type of adulteration by analyzing differences in composition between EOs or by spectroscopic analysis [26,28,80][26][28][78]. As adulterações ao longo da cadeia alimentar retions along the food chain presentam um perigo para a saúde e a vigilância contínua é a health hazard, and continuous vigilance is fundamental em termos de segurança alimentar, no que diz respeito à investigação e desenvolvimento de métodos analíticos parain terms of food safety, regarding research and development of analytical methods to detectar adulterações etions and contaminações nos alimentos a partir das matérias-primas utilizadastion in food from the raw materials used [26 ] [26].References

- Prakash, A.; Baskaran, R.; Paramasivam, N.; Vadivel, V. Essential oil based nanoemulsions to improve the microbial quality of minimally processed fruits and vegetables: A Review. Food Res. Int. 2018, 111, 509–523.

- Silvestre, W.P.; Livinalli, N.F.; Baldasso, C.; Tessaro, I.C. Pervaporation in the separation of essential oil components: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 42–52.

- Ribeiro-santos, R.; Andrade, M.; Madella, D.; Martinazzo, A.P.; de Aquino Garcia, L.; Melo, N.; Sanches-Silva, A. Revisiting an Ancient Spice with Medicinal Purposes: Cinnamon. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 62, 154–169.

- Mith, H.; Duré, R.; Delcenserie, V.; Zhiri, A.; Daube, G.; Clinquart, A. Antimicrobial activities of commercial essential oils and their components against food-borne pathogens and food spoilage bacteria. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 2, 403–416.

- Yadav, M.K.; Chae, S.-W.; Im, G.J.; Chung, J.-W.; Song, J.-J. Eugenol: A phyto-compound effective against methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus clinical strain biofilms. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119564.

- Abbaszadeh, S.; Sharifzadeh, A.; Shokri, H.; Khosravi, A.R.; Abbaszadeh, A. Antifungal efficacy of thymol, carvacrol, eugenol and menthol as alternative agents to control the growth of food-relevant fungi. J. Mycol. Med. 2014, 24, e51–e56.

- Labib, G.S.; Aldawsari, H. Innovation of natural essential oil-loaded orabase for local treatment of oral candidiasis. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2015, 9, 3349–3359.

- Minozzo, M.; de Souza, M.A.; Bernardi, J.L.; Puton, B.M.S.; Valduga, E.; Steffens, C.; Paroul, N.; Cansian, R.L. Antifungal Activity and aroma persistence of free and encapsulated cinnamomum cassia essential oil in maize. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 394, 110178.

- Zin, W.A.; Silva, A.G.L.S.; Magalhães, C.B.; Carvalho, G.M.C.; Riva, D.R.; Lima, C.C.; Leal-Cardoso, J.H.; Takiya, C.M.; Valença, S.S.; Saldiva, P.H.N.; et al. Eugenol attenuates pulmonary damage induced by diesel exhaust particles. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 112, 911–917.

- Abuohashish, H.M.; Khairy, D.A.; Abdelsalam, M.M.; Alsayyah, A.; Ahmed, M.M.; Al-Rejaie, S.S. In-vivo assessment of the osteo-protective effects of eugenol in alveolar bone tissues. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 97, 1303–1310.

- Yang, C.X.; Wu, H.T.; Li, X.X.; Wu, H.Y.; Niu, T.X.; Wang, X.N.; Lian, R.; Zhang, G.L.; Hou, H.M. Comparison of the inhibitory potential of benzyl isothiocyanate and phenethyl isothiocyanate on shiga toxin-producing and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. LWT 2020, 118, 108806.

- Dawidowicz, A.L.; Olszowy, M. Does antioxidant properties of the main component of essential oil reflect its antioxidant properties? the comparison of antioxidant properties of essential oils and their main components. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 1952–1963.

- Bhagya, H.P.; Raveendra, Y.C.; Lalithya, K.A. Mulibenificial uses of spices: A brief review. Acta Sci. Nutr. Health 2017, 1, 3–6.

- Jakhetia, V.; Patel, R.; Khatri, P.; Pahuja, N.; Garg, S.; Pandey, A.; Sharma, S. Cinnamon: A pharmacological review. J. Adv. Sci. Res. 2010, 1, 19–23.

- Barceloux, D.G. Cinnamon (Cinnamomum species). Disease-a-Month 2009, 55, 327–335.

- Medagama, A.B. The Glycaemic outcomes of cinnamon, a review of the experimental evidence and clinical trials. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 108.

- Shreaz, S.; Wani, W.A.; Behbehani, J.M.; Raja, V.; Irshad, M.; Karched, M.; Ali, I.; Siddiqi, W.A.; Hun, L.T. Cinnamaldehyde and its derivatives, a novel class of antifungal agents. Fitoterapia 2016, 112, 116–131.

- Nabavi, S.F.; Di Lorenzo, A.; Izadi, M.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; Daglia, M.; Nabavi, S.M. Antibacterial effects of cinnamon: From farm to food, cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7729–7748.

- Barbosa, R.F.S.; Yudice, E.D.C.; Mitra, S.K.; Rosa, D.S. Characterization of rosewood and cinnamon cassia essential oil polymeric capsules: Stability, loading efficiency, release rate and antimicrobial properties. Food Control 2021, 121, 107605.

- Muhammad, D.R.A.; Praseptiangga, D.; Van de Walle, D.; Dewettinck, K. Interaction between natural antioxidants derived from cinnamon and cocoa in binary and complex mixtures. Food Chem. 2017, 231, 356–364.

- Duguta, T.; Cheriyan, B.V. An introduction and various phytochemical studies of cinnamomum malabatrum: A brief review. Pharmacogn. J. 2021, 13, 792–797.

- De Oliveira Cardoso, R.; Gancedo, N.C.; Defani, M.A. Efeito Hipoglicemiante da canela (Cinnamomum sp.) e pata-de-vaca (Bauhinia sp.): Revisão bibliográfica. Arq. do Mudi 2019, 23, 399–412.

- Clouet, E.; Bechara, R.; Raffalli, C.; Damiens, M.-H.; Groux, H.; Pallardy, M.; Ferret, P.-J.; Kerdine-Römer, S. The THP-1 cell toolbox: A new concept integrating the key events of skin sensitization. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 941–951.

- Hossein, N.; Zahra, Z.; Abolfazl, M.; Mahdi, S.; Ali, K. Effect of Cinnamon zeylanicum essence and distillate on the clotting time. J. Med. Plants Res. 2013, 7, 1339–1343.

- Lopes, J.D.S.; Salesde Lima, A.B.; da Cruz Cangussu, R.R.; da Silva, M.V.; Ferrão, S.P.B.; Santos, L.S. Application of spectroscopic techniques and chemometric methods to differentiate between true cinnamon and false cinnamon. Food Chem. 2022, 368, 130746.

- Cantarelli, M.Á.; Moldes, C.A.; Marchevsky, E.J.; Azcarate, S.M.; Camiña, J.M. Low-cost analytic method for the identification of cinnamon adulteration. Microchem. J. 2020, 159, 105513.

- Farag, M.A.; Labib, R.M.; Noleto, C.; Porzel, A.; Wessjohann, L.A. NMR Approach for the authentication of 10 cinnamon spice accessions analyzed via chemometric tools. LWT 2018, 90, 491–498.

- Wang, Y.-H.; Avula, B.; Nanayakkara, N.P.D.; Zhao, J.; Khan, I.A. Cassia cinnamon as a source of coumarin in cinnamon-flavored food and food supplements in the United States. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 4470–4476.

- Yasmin, J.; Ahmed, M.R.; Lohumi, S.; Wakholi, C.; Lee, H.; Mo, C.; Cho, B.-K. Rapid authentication measurement of cinnamon powder using FT-NIR and FT-IR Spectroscopic techniques. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crop Foods 2019, 11, 257–267.

- Abraham, K.; Wöhrlin, F.; Lindtner, O.; Heinemeyer, G.; Lampen, A. Toxicology and risk assessment of coumarin: Focus on human data. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010, 54, 228–239.

- Shawky, E.; Selim, D. Rapid authentication and quality evaluation of Cinnamomum verum powder using near-infrared spectroscopy and multivariate analyses. Planta Med. 2018, 84, 1380–1387.

- European Parliament; Council of the the European Union Regulation. (EC) No 1334/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on Flavourings and Certain Food Ingredients with Flavouring Properties for Use in and on Foods and Amending Council Regulation (EEC) No 1601/91, Regulations, Regulations (EC) No 2232/96 and (EC) No 110/2008 and Directive 2000/13/EC. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, L354, 34–50.

- Scherner, M.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Salvati, D. Evaluation of information on cinnamon sold in brazil at fairs, natural product stores and markets. In Open Science Research IV; Editora Científica Digital: Online, São Paulo, Brasil, 2022; pp. 38–44. ISBN 9786553601413.

- Kawatra, P.; Rajagopalan, R. Cinnamon: Mystic powers of a minute ingredient. Pharmacogn. Res. 2015, 7, 1.

- Chen, P.-Y.; Yu, J.-W.; Lu, F.-L.; Lin, M.-C.; Cheng, H.-F. Differentiating parts of Cinnamomum cassia using lc-qtof-ms in conjunction with principal component analysis. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2016, 30, 1449–1457.

- Ghosh, T.; Basu, A.; Adhikari, D.; Roy, D.; Pal, A.K. Antioxidant activity and structural features of Cinnamomum zeylanicum. 3 Biotech 2015, 5, 939–947.

- Gu, D.-T.; Tung, T.-H.; Jiesisibieke, Z.L.; Chien, C.-W.; Liu, W.-Y. Safety of cinnamon: An umbrella review of meta-analyses and systematic reviews of randomized clinical trials. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12, 790901.

- Scherer, R.; Wagner, R.; Duarte, M.C.T.; Godoy, H.T. Composition and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of clove, citronella and palmarosa essential oils. Rev. Bras. Plantas Med. 2009, 11, 442–449.

- Zhang, Y.; Long, Y.; Yu, S.; Li, D.; Yang, M.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wan, J.; Liu, S.; Shi, A.; et al. Natural Volatile oils derived from herbal medicines: A promising therapy way for treating depressive disorder. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 164, 105376.

- De Castro, H.G.; de Moura Perini, V.B.; dos Santos, G.R.; Leal, T.C.A.B. Evaluation of the content and composition of Cymbopogon nardus (L.) essential oil at different harvest times. Rev. Ciência Agronômica 2010, 41, 308–314.

- Muhammad, D.R.A.; Dewettinck, K. Cinnamon and its derivatives as potential ingredient in functional food—A review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 2237–2263.

- Chen, G.; Sun, F.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Dong, J.; Gao, F. Enhanced extraction of essential oil from Cinnamomum cassia bark by ultrasound assisted hydrodistillation. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 36, 38–46.

- Friedman, M. Chemistry, Antimicrobial mechanisms, and antibiotic activities of cinnamaldehyde against pathogenic bacteria in animal feeds and human foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 10406–10423.

- Ashakirin, S.N.; Tripathy, M.; Patil, U.K.; Majeed, A.B.A. Chemistry and bioactivity of cinnamaldehyde: A natural molecule of medicinal importance. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2017, 8, 2333–2340.

- Friedman, M.; Kozukue, N.; Harden, L.A. Cinnamaldehyde content in foods determined by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 5702–5709.

- Das, G.; Gonçalves, S.; Basilio Heredia, J.; Romano, A.; Jiménez-Ortega, L.A.; Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E.P.; Shin, H.S.; Patra, J.K. Cardiovascular protective effect of cinnamon and its major bioactive constituents: An Update. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 97, 105045.

- Dorri, M.; Hashemitabar, S.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) as an antidote or a protective agent against natural or chemical toxicities: A review. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 41, 338–351.

- Hariri, M.; Ghiasvand, R. Cinnamon and chronic diseases. In Drug Discovery from Mother Nature; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–24.

- Cao, T.L.; Song, K.B. Development of bioactive bombacaceae gum films containing cinnamon leaf essential oil and their application in packaging of fresh salmon fillets. LWT 2020, 131, 109647.

- Marchese, A.; Barbieri, R.; Coppo, E.; Orhan, I.E.; Daglia, M.; Nabavi, S.F.; Izadi, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Nabavi, S.M.; Ajami, M. Antimicrobial activity of eugenol and essential oils containing eugenol: A mechanistic viewpoint. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 43, 668–689.

- Mishra, S.; Sachan, A.; Sachan, S.G. Production of natural value-added compounds: An insight into the eugenol biotransformation pathway. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 40, 545–550.

- Sebaaly, C.; Haydar, S.; Greige-Gerges, H. Eugenol encapsulation into conventional liposomes and chitosan-coated liposomes: A comparative study. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 67, 102942.

- Yalkowsky, S.H.; He, Y.; Jain, P. Handbook of Aqueous Solubility Data; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; p. 687. ISBN 0367384175.

- Chen, F.; Du, X.; Zu, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, F. Microwave-assisted method for distillation and dual extraction in obtaining essential oil, proanthocyanidins and polysaccharides by one-pot process from cinnamomi cortex. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 164, 1–11.

- Burt, S. Essential oils: Their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods—A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253.

- Ojeda-Sana, A.M.; van Baren, C.M.; Elechosa, M.A.; Juárez, M.A.; Moreno, S. New Insights into antibacterial and antioxidant activities of rosemary essential oils and their main components. Food Control 2013, 31, 189–195.

- Pandey, A.; Chattopadhyay, P.; Banerjee, S.; Pakshirajan, K.; Singh, L. Antitermitic activity of plant essential oils and their major constituents against termite Odontotermes Assamensis holmgren (Isoptera: Termitidae) of North East India. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2012, 75, 63–67.

- Cheng, S.-S.; Liu, J.-Y.; Huang, C.-G.; Hsui, Y.-R.; Chen, W.-J.; Chang, S.-T. Insecticidal activities of leaf essential oils from Cinnamomum osmophloeum against three mosquito species. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 457–464.

- Viteri Jumbo, L.O.; Faroni, L.R.A.; Oliveira, E.E.; Pimentel, M.A.; Silva, G.N. Potential use of clove and cinnamon essential oils to control the bean weevil, acanthoscelides obtectus say, in small storage units. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 56, 27–34.

- Wang, Y.; Dai, P.-P.; Guo, S.; Cao, J.; Pang, X.; Geng, Z.; Sang, Y.-L.; Du, S.-S. Supercritical carbon dioxide extract of Cinnamomum Cassia bark: Toxicity and repellency against two stored-product beetle species. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 22236–22243.

- Durak, A.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Pecio, Ł. Coffee with cinnamon—Impact of phytochemicals interactions on antioxidant and anti-inflammatory in vitro activity. Food Chem. 2014, 162, 81–88.

- Guo, J.; Yang, R.; Gong, Y.; Hu, K.; Hu, Y.; Song, F. Optimization and evaluation of the ultrasound-enhanced subcritical water extraction of cinnamon bark oil. LWT 2021, 147, 111673.

- Kuspradini, H.; Putri, A.S.; Sukaton, E.; Mitsunaga, T. Bioactivity of essential oils from leaves of Dryobalanops Lanceolata, Cinnamomum burmannii, Cananga odorata, and Scorodocarpus borneensis. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 9, 411–418.

- Mutlu, M.; Bingol, Z.; Uc, E.M.; Köksal, E.; Goren, A.C.; Alwasel, S.H.; Gulcin, İ. Comprehensive metabolite profiling of cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) leaf oil using LC-HR/MS, GC/MS, and GC-FID: Determination of antiglaucoma, antioxidant, anticholinergic, and antidiabetic profiles. Life 2023, 13, 136.

- Przygodzka, M.; Zielińska, D.; Ciesarová, Z.; Kukurová, K.; Zieliński, H. Comparison of methods for evaluation of the antioxidant capacity and phenolic compounds in common spices. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 58, 321–326.

- Yu, T.; Lee, S.; Yang, W.S.; Jang, H.-J.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, T.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, J.; Cho, J.Y. The ability of an ethanol extract of Cinnamomum cassia to inhibit src and spleen tyrosine kinase activity contributes to its anti-inflammatory action. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 139, 566–573.

- Sahib, A. Antidiabetic and antioxidant effect of cinnamon in poorly controlled type-2 diabetic iraqi patients: A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 5, 108.

- Kim, S.H.; Hyun, S.H.; Choung, S.Y. Anti-diabetic effect of cinnamon extract on blood glucose in Db/Db Mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 104, 119–123.

- Li, R.; Liang, T.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Duan, X. Protective effect of cinnamon polyphenols against stz-diabetic mice fed high-sugar, high-fat diet and its underlying mechanism. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 51, 419–425.

- Lee, S.-C.; Xu, W.-X.; Lin, L.-Y.; Yang, J.-J.; Liu, C.-T. Chemical composition and hypoglycemic and pancreas-protective effect of leaf essential oil from indigenous cinnamon (Cinnamomum Osmophloeum Kanehira). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 4905–4913.

- Vaillancourt, K.; LeBel, G.; Yi, L.; Grenier, D. In vitro antibacterial activity of plant essential oils against Staphylococcus hyicus and Staphylococcus aureus, the causative agents of exudative epidermitis in pigs. Arch. Microbiol. 2018, 200, 1001–1007.

- LeBel, G.; Vaillancourt, K.; Bercier, P.; Grenier, D. Antibacterial activity against porcine respiratory bacterial pathogens and in vitro biocompatibility of essential oils. Arch. Microbiol. 2019, 201, 833–840.

- Sahal, G.; Woerdenbag, H.J.; Hinrichs, W.L.J.; Visser, A.; Tepper, P.G.; Quax, W.J.; van der Mei, H.C.; Bilkay, I.S. Antifungal and biofilm inhibitory effect of cymbopogon citratus (Lemongrass) essential oil on biofilm forming by candida tropicalis isolates; an in vitro study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 246, 112188.

- De Fátima Dantas de Almeida, L.; de Paula, J.F.; Dantas de Almeida, R.V.; Williams, D.W.; Hebling, J.; Cavalcanti, Y.W. Efficacy of citronella and cinnamon essential oils on Candida albicans biofilms. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2016, 74, 393–398.

- Campana, R.; Casettari, L.; Fagioli, L.; Cespi, M.; Bonacucina, G.; Baffone, W. Activity of essential oil-based microemulsions against Staphylococcus Aureus biofilms developed on stainless steel surface in different culture media and growth conditions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 241, 132–140.

- Firmino, D.F.; Cavalcante, T.T.A.; Gomes, G.A.; Firmino, N.C.S.; Rosa, L.D.; de Carvalho, M.G.; Catunda, F.E.A., Jr. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of Cinnamomum sp. essential oil and cinnamaldehyde: Antimicrobial activities. Sci. World J. 2018, 2018, 7405736.

- Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Ying, G.; Yang, M.; Nian, Y.; Wei, F.; Kong, W. Antifungal Evaluation of plant essential oils and their major components against toxigenic fungi. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 120, 180–186.

- Cuchet, A.; Anchisi, A.; Schiets, F.; Carénini, E.; Jame, P.; Casabianca, H. Δ18O Compound-specific stable isotope assessment: An advanced analytical strategy for sophisticated adulterations detection in essential oils—Application to spearmint, cinnamon, and bitter almond essential oils authentication. Talanta 2023, 252, 123801.

- Syafri, S.; Jaswir, I.; Yusof, F.; Rohman, A.; Ahda, M.; Hamidi, D. The use of instrumental technique and chemometrics for essential oil authentication: A review. Results Chem. 2022, 4, 100622.

- Gopu, C.L.; Aher, S.; Mehta, H.; Paradkar, A.R.; Mahadik, K.R. Simultaneous Determination of cinnamaldehyde, eugenol and piperine by HPTLC densitometric method. Phytochem. Anal. 2008, 19, 116–121.

- Do, T.K.T.; Hadji-Minaglou, F.; Antoniotti, S.; Fernandez, X. Authenticity of essential oils. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2015, 66, 146–157.

- Remaud, G.; Debon, A.A.; Martin, Y.; Martin, G.G.; Martin, G.J. Authentication of bitter almond oil and cinnamon oil: Application of the SNIF-NMR method to benzaldehyde. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 4042–4048.

More