Epigenetic modifications modulate gene expression without any change in genomic DNA sequences that affects multiple aspects of plant growth and development

- Quantitative Epigenetics

1. Introduction

Epigenetic modifications modulate gene expression without any change in genomic DNA sequences that affects multiple aspects of plant growth and development[1] [1]. These epigenetic modification starts mainly involve DNA methylation, histone modification, and small RNA (sRNA)-mediated modifications[2] [2]. Of these epigenetic modifications, DNA methylation is relatively well studied. In plants, DNA methylation predominantly occurs in the cytosines (C) of three sequence contexts: CpG, CpHpG, and CpHpH, where H represents any base other than G (i.e., A/C/T). DNA methylation at each sequence context is regulated by a particular set of enzymes named cytosine-5 DNA methyltransferases (C5-MTases) having complementary ‘de novo’ and ‘maintenance’ methylation activities[3][4] [3,4]. In the de novo methylation process, unmethylated cytosine residues are methylated, while in methylation maintenance the preexisting methylation patterns are maintained after DNA replication [5]. Different C5-MTases including Domains Rearranged Methylases (DRMs), Methyltransferases (METs), and Chromomethylases (CMTs) participate in these processes. The DRMs are involved in de novo DNA methylation via RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) in all three DNA sequence contexts[6] [6]. The DRM2, an ortholog of mammalian DNMT3, is involved in CpHpH methylation of euchromatic regions[7] [7]. The METs are involved in the maintenance of CpG methylation during DNA replication[8] [8]. The CMTs are involved in the maintenance of CpHpG and CpHpH methylations. In Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh (Arabidopsis), CMT2 catalyzes CpHpH methylation, while CpHpG methylation is catalyzed by CMT3 and to a lesser extent by CMT2[9][10] [9,10]. The roles of DNA methylation in plant development and responses to environmental stress conditions have been discussed in detail previously[11] [11].

2. Epigenetic Recombinant Inbred Lines (epiRILs)

EpiRILs are referred to as the recombinant inbred lines that differ for DNA methylation patterns and show no genetic variation. EpiRILs represent an excellent resource to identify the effect of DNA-methylation on phenotypes[12] [34]. Under changing climatic conditions, epigenetic modifications could play a crucial role in plant adaptation to environmental stresses[13] [61]. epiRILs developed in Arabidopsis have been used to explore the effect of environmental factors, which revealed that stress-induced epigenetic modifications could be heritable and provide phenotypic plasticity to plants to endure stress[14] [62].

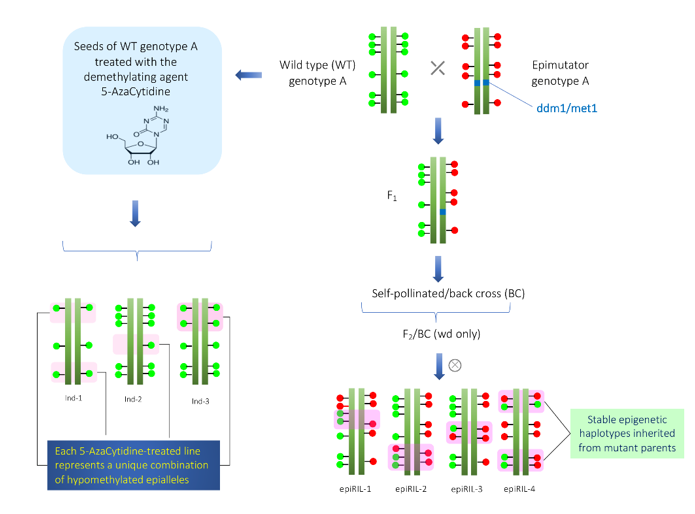

In Arabidopsis, at least two different epi-RIL populations have been developed[12][15] [34,63]. One epi-RIL population was derived from the crossing of met1 mutant and its isogenic wild type[15] [63]. The met1 mutant is defective in DNA methyltransferase[8][16] [8,64]. In the F2 and subsequent generations, only wild type MET1 alleles were selected in order to prevent de novo DNA methylations. In each generation, progenies were advanced using the single seed descent method. Similarly, another epi-RIL population was derived from the crossing of ddm mutant and its isogenic wild type[12] [34]. The ddm mutant is defective in the DDM locus that encodes nucleosome-remodeling ATPase required to maintain C methylation [17][18][65,66]. Due to the utilization of isogenic lines in crossing, these epiRILs have no genetic variations; however, epigenetic variations are maximum. Schematic representation of the development of epiRILs is given in Figure 1. The following points need to be considered while studying transgenerational epigenetic variations.

Figure 1. Construction of epiRILs (hypomethylated population) for quantitative epigenetics. In the left side, the scheme for the construction of hypomethylated population using demethylating agent 5-AzaCytidine is shown. On the right side, scheme for construction of epiRILs with stable inheritance by crossing of two parents (wild-type and epimutator parents (met1 or ddm1)) with different epigenetic states is shown. The green and red circles that overlay the genome sequence illustrates the different epigenetic states of the two parents.

2.1. Persistence of Epigenetic Modification in the epiRILs

3.1. Persistence of Epigenetic Modification in the epiRILs

Epigenetic modifications are heritable and maintained across several generations as revealed from epiRILs developed by the crossing of mutants (met1 or ddm1) with its isogenic wild types[19][20] [67,68]. In the ddm epiRILs, epigenetic loci targeted by small RNAs were extensively remethylated, while nontargeted loci remained unmethylated[21] [69]. In contrast, Flowering Wageningen (FWA) epiallele associated with flowering time became methylated in the subsequent generations despite being targeted by small RNA[12][15] [34,63]. The mechanism underlying remethylation process and the role of small RNAs in remethylation remain unclear. However, a recent study provides mechanistic insights on the formation and transmission of epialleles and suggested that histone and DNA methylation marks are critical in determining the ability of RdDM target loci to form stable epialleles[22] [70]. High levels of active histone mark H3K4me3 at specific loci prevent recruitment of the RdDM machinery, whereas high levels of H3K18ac enable ROS1 (Repressor of Silencing 1) to access specific loci, therefore antagonizing RdDM-mediated re-establishment of DNA methylation.

2.2. Phenotypic Variation and Stability in the epiRILs

3.2. Phenotypic Variation and Stability in the epiRILs

Continuous variations for different traits observed in the abovementioned two epi-RILs suggested that epigenetic modification was involved in the regulation of polygenic traits also. Although two epi-RILs differed for different traits. For instance, epiRILs derived from met1 mutant showed variation for biotic (bacterial pathogen) and abiotic stress (salt) tolerance [63]; however, in the case of epiRILs derived from ddm1 mutant, variation can be clearly seen for morphological traits like flowering time and plant height[12] [34].

The stability of phenotypic characters in the above two epiRILs is quite different. Phenotypes in met1 derived epiRILs are very unstable, and several lines were unable to advance to F8 generation due to abnormal development and infertility [63]. Unlike, ddm1 derived epiRILs were found highly stable and more than 99% lines advanced to F8 generations without any abnormality [12][34].

To explain phenotypic instability, Reinder et al.[15] [63] studied the methylation pattern in met1-derived epiRILs. They found that some cytosine methylation sites were highly segregating even in F8/F9 generations and suggested that some methylations sites are very unstable and cannot be fixed by repeated selfing. Furthermore, several ectopic and hypomethylations were observed that were different from any of the parental genotypes, suggesting de-novo methylations may be a possible reason for the phenotypic and epigenetic instability across generations in met1 derived epiRILs[15] [63]. In contrast, in ddm1-derived epiRILs, cytosine remethylation seems to be the reason for nonparental cytosine methylation[21] [69].

2.3. Epigenetic Basis of Heterosis

3.3. Epigenetic Basis of Heterosis

Heterosis is a phenomenon where F1 hybrid shows enhanced phenotypes than their respective parents. Heterosis has extensively been exploited as a potential breeding strategy for crop improvement. The importance of heterosis, its application in plant breeding, and molecular mechanisms underlying heterosis have been discussed elsewhere[23][24][25][26] [71–74]. Many genetic factors contribute to the heterotic phenotype; however, epigenetic interactions between two parental alleles also play a critical role in heterosis[27][28] [75,76]. Hybrids of Arabidopsis derived from two genetically similar but epigenetically diverse ecotypes C24 and Ler showed more than 250% enhanced biomass over parents advocated the importance of epigenetics in heterosis[29] [77]. Out of three different cytosine methylation contexts, the highest alteration was observed at CpG site; however, CpHpH and CpHpG methylations slightly increased in hybrids than parental genotypes[27] [75]. Furthermore, 75% methylation changes were observed in TEs , and more than 95% methylation increase was observed in siRNA generating regions[27] [75]. In Arabidopsis, hybrids derived from Col-wt (female parent) and 19 epiRILs (male parents) showed positive and negative heterosis for six growth-related traits. DNA methylation profiling of hybrids and parents identified epiQTLs associated with heterosis and suggested that DMRs present in the parental genotypes are responsible for heterosis[26] [74]. The above results provide evidence that epigenetic