| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bruno Miranda | + 2700 word(s) | 2700 | 2021-05-12 08:39:36 | | | |

| 2 | Bruno Miranda | + 1 word(s) | 2701 | 2021-05-18 13:22:03 | | | | |

| 3 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 2701 | 2021-05-19 04:51:04 | | |

Video Upload Options

Optical biosensors based on nanostructured materials have obtained increasing interest since they allow the screening of a wide variety of biomolecules with high specificity, low limits of detection, and great sensitivity. Among them, flexible optical platforms have the advantage of adapting to non-planar surfaces, suitable for in vivo and real-time monitoring of diseases and assessment of food safety.

1. Introduction

Optical biosensors have emerged as analytical devices for the rapid [1], cost-effective [2], selective [3], and specific detection of biological compounds (antibodies, nucleic acids, peptides, toxins, etc.), as well as bacteria [4], viruses [5][6], and cells [7]. The specificity of biosensors is an intrinsic property arising from the biorecognition probe immobilized on the surface of the transducing element. To this aim, noble metals nanomaterials represent very efficient transducers, due to their capability of supporting localized surface plasmons (LSPs) [8] and of significantly enhancing Raman scattering of molecules adsorbed onto their surface (SERS) [9].

Localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) is the size and shape-dependent coherent oscillation of the conduction electrons of a noble metal, arising when the size of the object is much smaller than the excitation wavelength [10][11][12][13][14]. The excitation of LSPs gives rise to a strong enhancement of the electromagnetic field in the surroundings of the nanoparticles, which makes their resonance locally sensitive to refractive index variations [15]. In particular, silver (Ag) and gold (Au) nanoparticles (NPs) have been studied deeply due to their capability of exhibiting LSPs in the visible region of the spectrum, thus allowing the design of refractive index [16][17] and colorimetric [18][19][20] optical biosensors. When a target analyte is recognized by the nanoparticles, a resonance shift, proportional to the concentration of the analyte, can be measured through UV-vis spectroscopy.

Noble metal nanoparticles immobilized onto a substrate can be used also for surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS). SERS is a sensitive and powerful optical technique providing resolutions up to single-molecule detection [21][22]. It has been extensively used for label-free biochemical assays and cell studies [23][24][25]. Two main mechanisms are involved in SERS: the charge transfer between the molecules and the substrate (chemical effect), and the LSPR modes of noble-metal nanoparticles (electromagnetic effect) [26][27]. SERS spectroscopy is performed to collect information about molecular vibrational states, guaranteeing high sensitivity to conformational changes [9]. Metallic nanoparticles provide the selected substrates with strong enhancement factors (EF) of the molecular Raman signals [28]. For SERS spectroscopy, strong efforts have been made to design and fabricate efficient substrates, with enhancement factors of the Raman signals up to 1014, to reach ultra-low limits of detection [29].

All the advantages shown by optical devices based on plasmonic nanoparticles have stimulated the continuous improvement of their fabrication techniques. The nanotechnological fabrication processes are based on two main approaches: top-down and bottom-up, which are sometimes combined to obtain a “hybrid approach” [30][31]. While the top-down approach usually requires nanolithographic techniques, which permits the mechanical or chemical etching of the bulk material, the bottom-up approach is based on the chemical synthesis of nanoparticles [32][33][34], starting from “molecular bricks.” In the case of the bottom-up approach some other methods are required to graft the nanomaterials onto the substrates, usually made of rigid materials (glass, silicon, quartz, etc.) [35][36][37].

The concept of flexible optical biosensors has been introduced more recently, due to the necessity of creating some optical platforms capable of adapting to non-planar surfaces, boosted by the advent of flexible electronics [38] and photonics [39]. This property finds its natural application in wearable sensors, conforming to the skin [40][41][42], food-packaging (sensors for food monitoring) [1][43], real-time monitoring of healing processes [44], and 3D cell cultures in scaffolds and organoids (cellular growth rate monitoring) [45]. Other advantages of flexible plasmonic substrates rely on the rapid, real-time, and cost-effective monitoring of a target analyte.

Flexibility allows rapid and high processability, thus extending plasmonic platforms to daily life applications [46]. For these reasons, many researchers have introduced very promising hybrid/nanocomposite transducers, based on the combination of synthetic or natural polymers with metallic nanoparticles. The combination of polymers with optically active nanomaterials generates platforms with extreme ease of integration within microfluidics and microelectronics devices, showing promising developments toward smart and efficient technologies.

Flexible biosensors find unprecedented applications in the design of wearable, point-of-care testing, and food monitoring devices. First, rigid substrates commonly employed for the accommodation of the plasmonic nanoparticles are difficult to employ as wearable sensors since they cannot easily adapt to skin. Also, rigid platforms on the skin could be uncomfortable and they could not find patient’s compliance [47]. Secondly, concerning POCT devices, researchers are moving toward the use of microfluidics to reduce sample volumes and enhance the capability of an analyte to interact with the bioprobe on the sensing surface. In this context, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) represent the gold standards to fabricate microfluidic channels [48][49]. The typical approach to combine microfluidics and rigid plasmonic substrates is the bonding of the two components. The final result is a microfluidic channel having only one wall covered with the transducing element. However, at the microscale, it may be worth having a channel completely covered with plasmonic nanoparticles to increase the detection efficiency and the contact area. While this is not possible with rigid substrates, it can be done with polymeric nanocomposites [50][51]. Finally, in food safety monitoring polymeric optical devices show appealing features to be easily integrated into food packaging, which is mainly involving polymeric materials [52][53].

The elasticity, bending capability, and stretchability of polymers over/in which plasmonic nanoparticles can be impregnated has been opening novel fundamental studies on the coupling mechanisms between plasmonic nanoparticles. This is something that was not feasible with rigid platforms. As an example, the optical response of plasmonic NPs dispersed in a polymeric film can be coupled by compression, due to the reduction of the distance among NPs, or can be decoupled by stretching the polymer [54]. For this reason, flexible nanoplasmonic is rapidly evolving in optomechanics, which combines theoretical physics with optics and material sciences [55][56]. Moreover, these platforms find applications in many other research fields, such as homeland security (i.e., drugs [57] and explosives [58][59] detection), seismology [60], and plant biology [61].

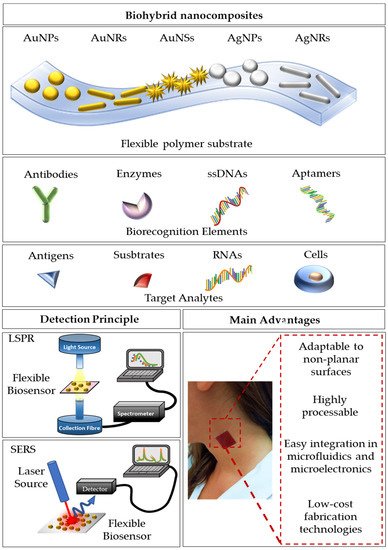

Figure 1 briefly schematizes the most used approaches to obtain functional biohybrid nanocomposites, together with the setups usually employed for their optical characterization and the main advantages. The most used nanomaterials are spherical gold and silver nanoparticles, but more complex shapes, such as nanorods and nanostars [29][62][63], are also employed for the fabrication of these optical devices. The shape and the size of the NPs are important design parameters to tune and optimize the optical responses. The biorecognition elements may include antibodies, enzymes, single-stranded DNAs, and/or aptamers, which provide the platform with high selectivity and specificity for the target analytes (antigens, substrates, RNAs, and cells). The LSPR optical setup usually consists of a white light source directly connected to an optical fiber probe. The resonant spectra can be collected in transmission mode if the device is optically transparent, or in reflectance mode, for devices with high reflectivity. A spectrometer is used to collect the transmitted/reflected light. Vice versa, a typical SERS setup consists of a laser source at different wavelengths, whose light is directly conveyed to the devices and collected with a CCD camera to register the Raman signal. In this review, we mainly focus on the description of LSPR-based flexible biosensors and SERS-based flexible biosensors, reporting the most innovative technologies and protocols for the fabrication of bio-responsive materials combining synthetic or natural polymers with gold or silver nanoparticles having diverse shapes and sizes.

Figure 1. A schematization of flexible optical biosensing platforms reporting the combination of a polymeric substrate with differently shaped gold/silver nanoparticles, the most used biorecognition elements, and target analytes. Furthermore, a schematization of the detection setups for LSPR and SERS signals is reported. Finally, the main advantages are summarized.

2. LSPR-Based Flexible Biosensors

The demand for optical biosensors based on LSPR rather than SPR has increased conspicuously in the last two decades. This is mainly due to the different spatial decay of the two sensing platforms. While surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) exploited for SPR are generated on a thin metallic surface (thickness ~10–250 nm) and have a large spatial decay, localized surface plasmons (LSPs), also known as non-propagating plasmons, are generated on noble-metal nanoparticles, which have characteristic dimensions always well below the excitation wavelength. In the second case, the spatial decay of the electromagnetic field is much smaller and limited to the surrounding of the NPs [64][65][66][67]. This significant difference allows the design of platforms, whose sensitivity is strictly associated with the surface of the NPs and independent from what happens far away from the surface (bulk) [32][33]. In this context, LSPR biosensors show appealing properties such as miniaturization, minimal interferences, and scalable production. However, while both periodic [34][35] and non-periodic [31] arrays of noble-metal nanoparticles on hard substrates have been already proposed as sensing platforms, there is still a lot of active research to propose novel approaches toward the fabrication of flexible, polymer-based LSPR biosensors. The main issue associated with the fabrication of such optical platforms is the limited number of polymers that can be used as substrates. A good LSPR biosensor must be highly transparent or reflective to allow the detection of the optical signal from noble metal nanoparticles. For this reason, opaque polymers, such as nanofibers (commonly employed as substrates for SERS-based biosensors) are not suitable for LSPR sensing.

3. SERS-Based Flexible Biosensors

SERS optical biosensors leverage on the design and fabrication of periodic, quasi-periodic, or random metal nanostructured arrays (nanohole arrays [68][69][70], nanocanals [71], porous structures [72][73][74][75][76][77], etc.) on rigid substrates (alumina, silicon, glass, etc.), showing very efficient performances, in terms of sensitivity and limits of detection. However, for the SERS measurements, the adsorption of the analyte of interest onto the surface is a necessary step, which is not always straightforward. It requires the extraction and the collection of the biomolecule and the selection of suitable surface chemistry for the successful binding of the analyte onto the substrate [78]. To obtain efficient and fast in situ detection, a rigid and opaque substrate may limit the applications to planar surfaces.

For this reason, the development of flexible, transparent substrates is very promising to overcome these issues, allowing the non-destructive detection of the target analytes. Among the currently used materials, we can distinguish between synthetic and natural polymers as SERS flexible substrates, whose performance is comparable to the previously mentioned rigid platforms [79][80].

4. Promising Applications of Flexible Biosensors

4.1. Point-of-Care Testing for Disease Diagnosis

There is an increasing demand for portable biosensors, where the clinical diagnostics is directly transferred from equipped laboratories to the patient on site-diagnosis. This need asks for renovated fabrication strategies of point-of-care testing (POCT) devices, which show ease-of-use, compact size, and limited costs [81][82]. Many examples of already commercialized POCT have been reviewed recently and include pregnancy tests, glucose testing, and HIV testing [83]. LSPR- and SERS-based flexible biosensors are promising transducers for the design of a POCT due to the ease of integration with microelectronics and microfluidics [84] (Figure 2a).

A first example of the integration of an LSPR platform with microfluidics has been reported by Huang et al. [87]. They introduced an approach to continuously monitoring the light transmission from an array of AuNPs arranged in a microfluidic channel. A green LED was used in substitution the typical halogen light source. The authors reported a sensitivity of 10−4 in RIU. The sensing capabilities of the proposed biosensor were shown by measuring the absorbance variation arisen from biotin/anti-biotin interaction. A LOD of 270 ng/mL was successfully achieved. This first example highlights the importance of the design process of both microfluidics and miniaturized optical components. More precisely, microfluidic channels must be highly transparent, to be compatible with light pathways, they should ensure an efficient sample delivery and minimize reagents and sample consumption [82]. On the other side, spectrometers and light sources (optical components) must be miniaturized to obtain a compact device and, although this is often not very easy, some methods to integrate LEDs for the transducer illumination and miniaturized spectrometers for the collection of the signal have been already proposed to overcome this issue [83]. POCTs for the diagnosis of disease especially in developing countries, where expensive laboratory equipment and specialized operators are not easily available are crucial for the rapid screening of a population. In this scenario, the low-cost polymers-based plasmonic devices offer the possibility to extend the modern lab technologies all over the world and give the less well-off the possibility to access to fast diagnosis and appropriate health care [88].

4.2. Wearable Sensors for Rapid Pre-Screening

The design of wearable biosensors for the early diagnosis of diseases has seen many efforts in sensors research. Unfortunately, these novel platforms generally suffer from low reproducibility in sensing capabilities as well as a lack of accuracy in the robust quantification of biomarkers from the skin due to the very tiny concentrations and species of targetable analytes in sweat. Moreover, some crucial issues are still topics of active research: data acquisition, processing, power supply, adaptability to non-planar surfaces (e.g., skin) [42]. Of course, sensitivity, selectivity, and low limits of detection are crucial in any sensing platform, but, in the case of wearable sensors, the collection of skin fluids from the body in a non-invasive way is still an open challenge. Some attempts involving textiles and hydrogels for their absorbing capability have been proposed. However, these materials are not suitable for the precise control of the collected volume.

The combination of micro-and nano-technology for flexible plasmonic biosensors has given rise to platforms with integrated functions all focusing on a single device having a few millimeters size. In these cases, microfluidics and microelectronics can be combined with flexible plasmonic platforms to produce wearable optical biosensors, whose readout can be performed to the naked eye or via integration with smartphones [41]. Wearable optical biosensors find their potential applications in the fast screening of the population for the detection of a target pathogen, which, in the era of SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), have revealed as crucial to avoid the pandemic spreading of disease. LSPR and SERS-based optical biosensors have already shown their potential in the detection of viral pathogens as SARS-Cov-2 [89][90][91]; for this reason, combining this to wearable biosensors by embedding the transducing elements on a flexible substrate could be a winning strategy to pursue, as reported also by Choe et al. [85] (Figure 2b).

4.3. Food Quality Monitoring

Due to the overall increase of the world population in the past decades, avoiding food waste is becoming a fundamental necessity; for this reason, the growing food industry is working on the improvement of the long-storage and preservation of food with novel packaging and delivery systems [53]. In this scenario, the biosensing of freshness markers, pathogens, allergens, and toxic agents in food is evolving toward the so-called smart active packaging [52]. Many sensors have been already proposed for food monitoring, but, again, some of the commonly encountered issues hide in the robustness, selectivity, and sensitivity of the proposed devices. Smart colorimetric labels could provide a “quality index” of the food by simply exhibiting a color variation visible to the naked eye [92]. Even though the implementation of some devices in smart and active packaging has already been proposed, for instance in refs. [53][93], one of the main challenges remains the achievement of a multiplexed sensing of the many different factors affecting the quality of certain food. Flexible optical biosensors have appealing multifunctional capabilities enabling both contaminants detection and longer shelf-life of food due to the sensing mechanisms, herein reported, and to the antimicrobial activity of noble-metal NPs [44][94]. For this reason, the use of polymers combined with optically active nanomaterials exhibit promising potential also in food quality monitoring. A smart application for the SERS-based detection of pesticides in fruits and vegetables has been reported in ref. [86] (Figure 2c), but many other flexible platforms are currently ready for these applications.

References

- Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Ying, Y. A simple and rapid optical biosensor for detection of aflatoxin B1 based on competitive dispersion of gold nanorods. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 47, 361–367.

- Yoo, S.M.; Lee, S.Y. Optical Biosensors for the Detection of Pathogenic Microorganisms. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 7–25.

- Mariani, S.; Scarano, S.; Spadavecchia, J.; Minunni, M. A reusable optical biosensor for the ultrasensitive and selective detection of unamplified human genomic DNA with gold nanostars. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 74, 981–988.

- Maphanga, C.; Manoto, S.L.; Ombinda-Lemboumba, S.S.; Hlekelele, L.; Mthunzi-Kufa, P. Optical biosensing of mycobacterium tuberculosis for point-of-care diagnosis. Proc. SPIE 2020, 11251.

- Yanik, A.A.; Huang, M.; Kamohara, O.; Artar, A.; Geisbert, T.W.; Connor, J.H.; Altug, H. An optofluidic nanoplasmonic biosensor for direct detection of live viruses from biological media. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 4962–4969.

- Baeumner, A.J.; Schlesinger, N.A.; Slutzki, N.S.; Romano, J.; Lee, E.M.; Montagna, R.A. Biosensor for dengue virus detection: Sensitive, rapid, and serotype specific. Anal. Chem. 2002, 74, 1442–1448.

- Endo, T.; Yamamura, S.; Kerman, K.; Tamiya, E. Label-free cell-based assay using localized surface plasmon resonance biosensor. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 614, 182–189.

- Forestiere, C.; Pasquale, A.J.; Capretti, A.; Miano, G.; Tamburrino, A.; Lee, S.Y.; Reinhard, B.M.; Dal Negro, L. Genetically engineered plasmonic nanoarrays. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 2037–2044.

- Alvarez-Puebla, R.A.; Liz-Marzán, L.M. SERS-based diagnosis and biodetection. Small 2010, 6, 604–610.

- Yang, H.; Huang, R.Q.; Hao, J.M.; Li, C.Y.; He, W. Theoretical Study on Effect of the Size of Silver Nanoparticles on the Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Spectrum of Silver Nanoparticles Embedded in BaO Thin Film. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2002, 3, 549–552.

- Park, C.S.; Lee, C.; Kwon, O.S. Conducting polymer based nanobiosensors. Polymers 2016, 8, 249.

- Nehl, C.L.; Hafner, J.H. Shape-dependent plasmon resonances of gold nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 2415–2419.

- Forestiere, C.; Miano, G.; Rubinacci, G. Resonance frequency and radiative Q-factor of plasmonic and dieletric modes of small objects. Phys. Rev. Res. 2020, 2.

- Maier, S.A. Plasmonics: Fundamentals and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007.

- Zalyubovskiy, S.J.; Bogdanova, M.; Deinega, A.; Lozovik, Y.; Pris, A.D.; An, K.H.; Hall, W.P.; Potyrailo, R.A. Theoretical limit of localized surface plasmon resonance sensitivity to local refractive index change and its comparison to conventional surface plasmon resonance sensor. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2012, 29, 994.

- Liu, Y.; Huang, C.Z. Screening sensitive nanosensors via the investigation of shape-dependent localized surface plasmon resonance of single Ag nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 7458–7466.

- Miranda, B.; Moretta, R.; De Martino, S.; Dardano, P.; Rea, I.; Forestiere, C.; De Stefano, L. A PEGDA hydrogel nanocomposite to improve gold nanoparticles stability for novel plasmonic sensing platforms. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 129, 033101.

- Zhao, W.; Brook, M.A.; Li, Y. Design of gold nanoparticle-based colorimetric biosensing assays. ChemBioChem 2008, 9, 2363–2371.

- Filippo, E.; Serra, A.; Manno, D. Poly(vinyl alcohol) capped silver nanoparticles as localized surface plasmon resonance-based hydrogen peroxide sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2009, 138, 625–630.

- Che Sulaiman, I.S.; Chieng, B.W.; Osman, M.J.; Ong, K.K.; Rashid, J.I.A.; Wan Yunus, W.M.Z.; Noor, S.A.M.; Kasim, N.A.M.; Halim, N.A.; Mohamad, A. A review on colorimetric methods for determination of organophosphate pesticides using gold and silver nanoparticles. Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 1–22.

- Qian, X.M.; Nie, S.M. Single-molecule and single-nanoparticle SERS: From fundamental mechanisms to biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 912–920.

- Kneipp, K.; Wang, Y.; Kneipp, H.; Perelman, L.T.; Itzkan, I.; Dasari, R.R.; Feld, M.S. Single molecule detection using surface-enhanced raman scattering (SERS). Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 1667–1670.

- Pramanik, A.; Chavva, S.R.; Viraka Nellore, B.P.; May, K.; Matthew, T.; Jones, S.; Vangara, A.; Ray, P.C. Development of a SERS Probe for Selective Detection of Healthy Prostate and Malignant Prostate Cancer Cells Using Zn II. Chem. An Asian J. 2017, 12, 665–672.

- Kneipp, J. Nanosensors Based on SERS for Applications in Living Cells. In Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 335–349.

- Lee, S.; Chon, H.; Yoon, S.Y.; Lee, E.K.; Chang, S.I.; Lim, D.W.; Choo, J. Fabrication of SERS-fluorescence dual modal nanoprobes and application to multiplex cancer cell imaging. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 124–129.

- Stiles, P.L.; Dieringer, J.A.; Shah, N.C.; Van Duyne, R.P. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2008, 1, 601–626.

- Jana, D.; Mandal, A.; De, G. High Raman enhancing shape-tunable Ag nanoplates in alumina: A reliable and efficient SERS technique. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 3330–3334.

- Zhong, L.B.; Yin, J.; Zheng, Y.M.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, X.X.; Luo, F.H. Self-assembly of Au nanoparticles on PMMA template as flexible, transparent, and highly active SERS substrates. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 6262–6267.

- Tiwari, V.S.; Oleg, T.; Darbha, G.K.; Hardy, W.; Singh, J.P.; Ray, P.C. Non-resonance SERS effects of silver colloids with different shapes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2007, 446, 77–82.

- Bhalla, N.; Sathish, S.; Sinha, A.; Shen, A.Q. Biosensors: Large-Scale Nanophotonic Structures for Long-Term Monitoring of Cell Proliferation (Adv. Biosys. 4/2018). Adv. Biosyst. 2018, 2, 1870031.

- Miranda, B.; Chu, K.-Y.; Maffettone, P.L.; Shen, A.Q.; Funari, R. Metal-Enhanced Fluorescence Immunosensor Based on Plasmonic Arrays of Gold Nanoislands on an Etched Glass Substrate. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020.

- Iarossi, M.; Schiattarella, C.; Rea, I.; De Stefano, L.; Fittipaldi, R.; Vecchione, A.; Velotta, R.; Ventura, B. Della Colorimetric Immunosensor by Aggregation of Photochemically Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 3805–3812.

- Aouidat, F.; Halime, Z.; Moretta, R.; Rea, I.; Filosa, S.; Donato, S.; Tatè, R.; De Stefano, L.; Tripier, R.; Spadavecchia, J. Design and Synthesis of Hybrid PEGylated Metal Monopicolinate Cyclam Ligands for Biomedical Applications. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 2500–2509.

- Politi, J.; Spadavecchia, J.; Fiorentino, G.; Antonucci, I.; De Stefano, L. Arsenate reductase from Thermus thermophilus conjugated to polyethylene glycol-stabilized gold nanospheres allow trace sensing and speciation of arsenic ions. J. R. Soc. Interface 2016, 13, 20160629.

- Luo, D. Nanotechnology and DNA delivery. MRS Bull. 2005, 30, 654–658.

- Iqbal, P.; Preece, J.A.; Mendes, P.M. Nanotechnology: The “Top-Down” and “Bottom-Up” Approaches. In Supramolecular Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2012.

- Teo, B.K.; Sun, X.H. From top-down to bottom-up to hybrid nanotechnologies: Road to nanodevices. J. Clust. Sci. 2006, 17, 529–540.

- Khan, Y.; Thielens, A.; Muin, S.; Ting, J.; Baumbauer, C.; Arias, A.C. A New Frontier of Printed Electronics: Flexible Hybrid Electronics. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1905279.

- Geiger, S.; Michon, J.; Liu, S.; Qin, J.; Ni, J.; Hu, J.; Gu, T.; Lu, N. Flexible and Stretchable Photonics: The Next Stretch of Opportunities. ACS Photonics 2020.

- Yang, J.C.; Mun, J.; Kwon, S.Y.; Park, S.; Bao, Z.; Park, S. Electronic Skin: Recent Progress and Future Prospects for Skin-Attachable Devices for Health Monitoring, Robotics, and Prosthetics. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1904765.

- Dervisevic, M.; Alba, M.; Prieto-Simon, B.; Voelcker, N.H. Skin in the diagnostics game: Wearable biosensor nano-and microsystems for medical diagnostics. Nano Today 2020, 30, 100828.

- Gao, Y.; Yu, L.; Yeo, J.C.; Lim, C.T. Flexible Hybrid Sensors for Health Monitoring: Materials and Mechanisms to Render Wearability. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1902133.

- Mustafa, F.; Andreescu, S. Chemical and biological sensors for food-quality monitoring and smart packaging. Foods 2018, 7.

- Jackson, J.; Burt, H.; Lange, D.; Whang, I.; Evans, R.; Plackett, D. The Design, Characterization and Antibacterial Activity of Heat and Silver Crosslinked Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Hydrogel Forming Dressings Containing Silver Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 96.

- Mishra, A.; Ferhan, A.R.; Ho, C.M.B.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Yoon, Y.J. Fabrication of Plasmon-Active Polymer-Nanoparticle Composites for Biosensing Applications. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. Green Technol. 2020, 1–10.

- Polavarapu, L.; Liz-Marzán, L.M. Towards low-cost flexible substrates for nanoplasmonic sensing. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 5288–5300.

- Dias, D.; Cunha, J.P.S. Wearable health devices—vital sign monitoring, systems and technologies. Sensors 2018, 18, 2414.

- Alkhalaf, Q.; Pande, S.; Palkar, R.R. Review of polydimethylsiloxane (pdms) as a material for additive manufacturing. In Innovative Design, Analysis and Development Practices in Aerospace and Automotive Engineering; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 265–275.

- Reddy Konari, P.; Clayton, Y.-D.; Vaughan, M.B.; Khandaker, M.; Hossan, M.R. micromachines Experimental Analysis of Laser Micromachining of Microchannels in Common Microfluidic Substrates. Micromachines 2021, 12, 138.

- Dallari, C.; Credi, C.; Lenci, E.; Trabocchi, A.; Cicchi, R.; Saverio Pavone, F. Nanostars-decorated microfluidic sensors for surface enhanced Raman scattering targeting of biomolecules. J. Phys. Photonics 2020, 2, 24008.

- Sin, M.L.; Mach, K.E.; Wong, P.K.; Liao, J.C. Advances and challenges in biosensor-based diagnosis of infectious diseases. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2014, 14, 225–244.

- Agrillo, B.; Balestrieri, M.; Gogliettino, M.; Palmieri, G.; Moretta, R.; Proroga, Y.; Rea, I.; Cornacchia, A.; Capuano, F.; Smaldone, G.; et al. Functionalized Polymeric Materials with Bio-Derived Antimicrobial Peptides for “Active” Packaging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 601.

- Narsaiah, K.; Jha, S.N.; Bhardwaj, R.; Sharma, R.; Kumar, R. Optical biosensors for food quality and safety assurance-A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 383–406.

- Minnai, C.; Di Vece, M.; Milani, P. Mechanical-optical-electro modulation by stretching a polymer-metal nanocomposite. Nanotechnology 2017, 28, 355702.

- Schweizerhof, S.; Demco, D.E.; Mourran, A.; Fechete, R.; Möller, M. Diffusion of Gold Nanorods Functionalized with Thermoresponsive Polymer Brushes. Langmuir 2018, 34, 8031–8041.

- Aslam, M.; Kalyar, M.A.; Raza, Z.A. Fabrication of nano-CuO-loaded PVA composite films with enhanced optomechanical properties. Polym. Bull. 1551, 78, 1551–1571.

- Teymourian, H.; Parrilla, M.; Sempionatto, J.R.; Montiel, N.F.; Barfidokht, A.; Van Echelpoel, R.; De Wael, K.; Wang, J. Wearable Electrochemical Sensors for the Monitoring and Screening of Drugs. ACS Sensors 2020, 5, 2679–2700.

- Wasilewski, T.; Gębicki, J. Emerging Strategies for Enhancing Detection of Explosives by Artificial Olfaction. Microchem. J. 2021, 164, 106025.

- Liu, R.; Li, Z.; Huang, Z.; Li, K.; Lv, Y. Biosensors for explosives: State of art and future trends. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 118, 123–137.

- Zhan, Z. Distributed acoustic sensing turns fiber-optic cables into sensitive seismic antennas. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2019, 91, 1–15.

- Giraldo, J.P.; Wu, H.; Newkirk, G.M.; Kruss, S. Nanobiotechnology approaches for engineering smart plant sensors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 541–553.

- Forestiere, C.; He, Y.; Wang, R.; Kirby, R.M.; Dal Negro, L. Inverse Design of Metal Nanoparticles’ Morphology. ACS Photonics 2016, 3, 68–78.

- Zhang, C.L.; Lv, K.P.; Cong, H.P.; Yu, S.H. Controlled assemblies of gold nanorods in PVA nanofiber matrix as flexible free-standing SERS substrates by electrospinning. Small 2012, 8, 648–653.

- Stewart, M.E.; Anderton, C.R.; Thompson, L.B.; Maria, J.; Gray, S.K.; Rogers, J.A.; Nuzzo, R.G. Nanostructured plasmonic sensors. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 494–521.

- Swierczewska, M.; Liu, G.; Lee, S.; Chen, X. High-sensitivity nanosensors for biomarker detection. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2641–2655.

- Li, X.; Zhang, T.; Yu, J.; Xing, C.; Li, X.; Cai, W.; Li, Y. Highly Selective and Sensitive Detection of Hydrogen Sulfide by the Diffraction Peak of Periodic Au Nanoparticle Array with Silver Coating. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 40702–40710.

- Wang, Q.; Wang, L. Lab-on-fiber: Plasmonic nano-arrays for sensing. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 7485–7499.

- Gupta, N.; Dhawan, A. Bridged-bowtie and cross bridged-bowtie nanohole arrays as SERS substrates with hotspot tunability and multi-wavelength SERS response. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 17899.

- Yang, Z.L.; Li, Q.H.; Ren, B.; Tian, Z.Q. Tunable SERS from aluminium nanohole arrays in the ultraviolet region. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 3909–3911.

- Yu, Q.; Golden, G. Probing the protein orientation on charged self-assembled monolayers on gold nanohole arrays by SERS. Langmuir 2007, 23, 8659–8662.

- Ko, H.; Tsukruk, V.V. Nanoparticle-Decorated Nanocanals for Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Small 2008, 4, 1980–1984.

- Netzer, N.L.; Qiu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, C.; Zhang, L.; Fong, H.; Jiang, C. Gold-silver bimetallic porous nanowires for surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 9606–9608.

- Panarin, A.Y.; Terekhov, S.N.; Kholostov, K.I.; Bondarenko, V.P. SERS-active substrates based on n-type porous silicon. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 256, 6969–6976.

- Yang, D.P.; Chen, S.; Huang, P.; Wang, X.; Jiang, W.; Pandoli, O.; Cui, D. Bacteria-template synthesized silver microspheres with hollow and porous structures as excellent SERS substrate. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 2038–2042.

- Terracciano, M.; Napolitano, M.; De Stefano, L.; De Luca, A.C.; Rea, I. Gold decorated porous biosilica nanodevices for advanced medicine. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 235601.

- Pannico, M.; Rea, I.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Musto, P.; Voelcker, N.H.; De Stefano, L. Electroless Gold-Modified Diatoms as Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Supports. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 1–6.

- Terracciano, M.; De Stefano, L.; Rea, I. Diatoms green nanotechnology for biosilica-based drug delivery systems. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 242.

- Park, S.; Lee, J.; Ko, H. Transparent and Flexible Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) Sensors Based on Gold Nanostar Arrays Embedded in Silicon Rubber Film. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 44088–44095.

- He, D.; Hu, B.; Yao, Q.-F.; Wang, K.; Yu, S.-H. Large-Scale Synthesis of Flexible Free-Standing SERS Substrates with High Sensitivity: Electrospun PVA Nanofibers Embedded with Controlled Alignment of Silver Nanoparticles. ACS nano 2009, 3.

- Roskov, K.E.; Kozek, K.A.; Wu, W.C.; Chhetri, R.K.; Oldenburg, A.L.; Spontak, R.J.; Tracy, J.B. Long-range alignment of gold nanorods in electrospun polymer nano/microfibers. Langmuir 2011, 27, 13965–13969.

- Ahmed, M.U.; Saaem, I.; Wu, P.C.; Brown, A.S. Personalized diagnostics and biosensors: A review of the biology and technology needed for personalized medicine. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2014, 34, 180–196.

- Li, C. zhong Special Topic: Point-of-Care Testing (POCT) and In Vitro Diagnostics (IVDs). J. Anal. Test. 2019, 3, 1–2.

- Chen, Y.-T.; Lee, Y.-C.; Lai, Y.-H.; Lim, J.-C.; Huang, N.-T.; Lin, C.-T.; Huang, J.-J. Review of Integrated Optical Biosensors for Point-of-Care Applications. Biosensors 2020, 10, 209.

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, J. Construction of Plasmonic Nano-Biosensor-Based Devices for Point-of-Care Testing. Small Methods 2017, 1, 1700197.

- Choe, A.; Yeom, J.; Shanker, R.; Kim, M.P.; Kang, S.; Ko, H. Stretchable and wearable colorimetric patches based on thermoresponsive plasmonic microgels embedded in a hydrogel film. NPG Asia Mater. 2018, 10, 912–922.

- Wang, P.; Wu, L.; Lu, Z.; Li, Q.; Yin, W.; Ding, F.; Han, H. Gecko-Inspired Nanotentacle Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Substrate for Sampling and Reliable Detection of Pesticide Residues in Fruits and Vegetables. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 2424–2431.

- Huang, C.; Bonroy, K.; Reekmans, G.; Laureyn, W.; Verhaegen, K.; De Vlaminck, I.; Lagae, L.; Borghs, G. Localized surface plasmon resonance biosensor integrated with microfluidic chip. Biomed. Microdevices 2009, 11, 893–901.

- Hauck, T.S.; Giri, S.; Gao, Y.; Chan, W.C.W. Nanotechnology diagnostics for infectious diseases prevalent in developing countries. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010, 62, 438–448.

- Funari, R.; Chu, K.Y.; Shen, A.Q. Detection of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein by gold nanospikes in an opto-microfluidic chip. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 169, 112578.

- Ventura, B.D.; Cennamo, M.; Minopoli, A.; Campanile, R.; Censi, S.B.; Terracciano, D.; Portella, G.; Velotta, R. Colorimetric test for fast detection of SARS-COV-2 in nasal and throat swabs. ACS Sensors 2020, 5, 3043–3048.

- Liu, H.; Dai, E.; Xiao, R.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, M.; Bai, Z.; Shao, Y.; Qi, K.; Tu, J.; Wang, C.; et al. Development of a SERS-based lateral flow immunoassay for rapid and ultra-sensitive detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM/IgG in clinical samples. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 329, 129196.

- Neethirajan, S.; Jayas, D.S. Nanotechnology for the Food and Bioprocessing Industries. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2011, 4, 39–47.

- Duan, N.; Shen, M.; Qi, S.; Wang, W.; Wu, S.; Wang, Z. A SERS aptasensor for simultaneous multiple pathogens detection using gold decorated PDMS substrate. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 230, 118103.

- Tao, C. Antimicrobial activity and toxicity of gold nanoparticles: Research progress, challenges and prospects. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 67, 537–543.