Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Laura Anselmi | + 2246 word(s) | 2246 | 2021-04-26 07:54:22 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | -21 word(s) | 2225 | 2021-05-18 04:05:06 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Anselmi, L. Genetic Heterogeneity of Pediatric AML. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/9720 (accessed on 04 March 2026).

Anselmi L. Genetic Heterogeneity of Pediatric AML. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/9720. Accessed March 04, 2026.

Anselmi, Laura. "Genetic Heterogeneity of Pediatric AML" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/9720 (accessed March 04, 2026).

Anselmi, L. (2021, May 17). Genetic Heterogeneity of Pediatric AML. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/9720

Anselmi, Laura. "Genetic Heterogeneity of Pediatric AML." Encyclopedia. Web. 17 May, 2021.

Copy Citation

Despite improvements in therapeutic protocols and in risk stratification, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) remains the leading cause of childhood leukemic mortality. Indeed, the overall survival accounts for ~70% but still ~30% of pediatric patients experience relapse, with poor response to conventional chemotherapy. Thus, there is an urgent need to improve diagnosis and treatment efficacy prediction in the context of this disease. Nowadays, in the era of high throughput techniques, AML has emerged as an extremely heterogeneous disease from a genetic point of view. Different subclones characterized by specific molecular profiles display different degrees of susceptibility to conventional treatments.

pediatric AML

NGS

clonal evolution

target therapy

1. Introduction

Pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (AML), with an incidence of approximately seven occurrences per 1 million children annually [1], still represents a challenge for pediatric oncologists. Even though patient outcome has significantly improved over the past 30 years [1], as survival rates have reached ~70%, still about 30% of children with AML experience disease recurrence, with a probability of overall survival (pOS) ranging between 29 and 38% [2][3][4][5]. Thus, given the high frequency of relapse in pediatric AML, a deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying disease recurrence is necessary.

2. Pediatric AML: Clinical Presentation

AML is a heterogeneous disease, from clinical behavior to morphology, immunophenotyping and genetic abnormalities, due to the abnormal proliferation of myeloid progenitor cells in the bone marrow [6]. It has some unique presentations, such as granulocytic sarcomas, subcutaneous nodules, infiltration of the gingiva and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [7]. Diagnosis is based on leukemic blasts evaluation from the bone marrow, considering the morphology, cytochemistry, immunophenotype, cytogenetics (conventional karyotyping complemented with FISH or reverse transcriptase PCR) and molecular characterization [6]. AML is then classified according to the 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) classification, which also considers karyotype and molecular aberrations, and has replaced the morphology-based French–American–British (FAB) classification [6]. Due to the poor outcome of some specific subtypes, risk-group stratification based on genetic abnormalities and response is essential, mainly in order to identify those with high-risk AML, which could benefit from a more intensive treatment [1] such as hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in first complete remission (CR) [8]. Despite an increasing knowledge about the landscape of molecular alterations in AML, there are still only few alternatives to standard intensive chemotherapy regimens used for induction and consolidation treatment protocols, considering that ~30% of the pediatric patients relapse after the achievement of CR. The development of new therapies able to overcome resistance/relapse is essential. To this aim, it is necessary to deeply characterize the mechanisms responsible for AML and progression.

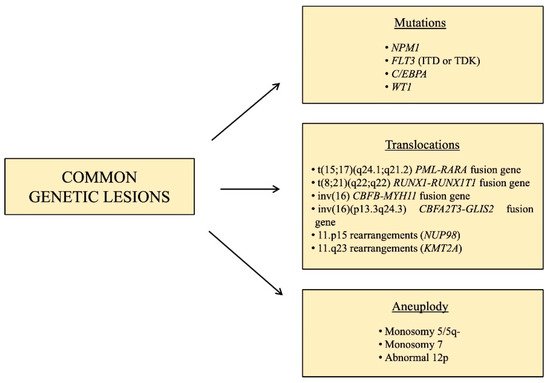

3. Pediatric AML: Common Genetic Lesions

Regardless of its heterogeneity, some characteristic chromosomal changes and molecular lesions are recurrent in pediatric AML (Figure 1). These include the translocation t(15;17)(q24.1;q21.2), that leads to the fusion of promyelocytic leukemia (PML) gene with the retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARA), in acute promyelocytic leukemia, which represent ~5% of pediatric AML [9]. This subtype of AML is highly peculiar and does not belong to any additional category, and its remission rates are >95% and overall survival is >80% [10], thanks to a target therapy consisting of all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) associated with arsenic trioxide (ATO), with the addition of the anti-CD33 gemtuzumabozogamicin in high-risk patients, defined as having WBC prior to treatment ≥10 × 109/

L [9].

Figure 1. Schematic resume of the main recurrent genetic lesions found in pediatric AML.

Other subtypes of pediatric AML, characterized by a favorable prognosis, are those involving core binding factor (CBF), accounting for approximately 20–25% of pediatric AML cases [11], such as t(8;21) (q22;q22) and inv(16),which lead to the fusion genes RUNX1-RUNX1T1 and CBFB-MYH11, respectively.

KMT2A is a histone methyltransferase that is rearranged in 35–60% of infants and 10–15% of children and adolescents [12], and it has almost 100 different fusion partners [13]. It represents a subgroup of pediatric AML with intermediate/unfavorable prognosis and for this reason, many specific drugs are in preclinical and clinical trials [14]. A subtype of pediatric AML with an unfavorable prognosis is that characterized by the fusion gene CBFA2T3-GLIS2, caused by inv(16) (p13.3q24.3), which is present in 15–20% of pediatric non-Down syndrome acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (non-DS-AMKL) and about 7–8% of pediatric AML with normal karyotype [15][16], mostly found in infant patients (<3 years) [17][18]. AMKL occurs particularly in children with Down syndrome, however, in contrast to DS-AMKL which display 80% of overall survival rate, non-DS-AMKL is associated with extremely poor prognosis [19][20]. Fusions involving the gene nucleoporin 98kD (NUP98) and over 30 different fusion partners, the most common of which are KDM5A and NDS1, can be found in 4–9% of pediatric AML [21]. The t(6;9) (p22;q34) leads to the expression of the fusion gene DEK-NUP214, present in just 1–2% of pediatric AML [22], whose role in leukemogenesis is unknown, but it is associated with a poor prognosis, due to the low rates of remission and high rates of relapse. A very rare cause of pediatric AML (less than 1%) associated with grim prognosis are translocations or inversions involving the MDS1 and EVI1 complex locus (MECOM) [13]. Aneuploidy, in the form of monosomy 5/5q-, monosomy 7 and abnormal 12p, are present in 4–9% of pediatric AML [12].

With the advent of large-scale genomic approaches, several molecular aberrations have been likewise identified, such as the gene nucleophosmin 1 (NPM1) which encodes for a chaperon protein normally localized predominantly in the nucleolus, however, when mutated, it is aberrantly localized in the cytoplasm, causing the activation of oncogenes. This is rarely altered in pediatric AML [23], but much more often in children (10%) and adolescents (20%) [12], and it often co-exists with FLT3-ITD mutations [24]. Another recurrent mutation in AML, especially in older children and adolescents, is that involving the gene CCAAT-enhancer binding protein alpha (C/EBPA), present in 5–10% of pediatric AML cases [12]. This is a very important transcription factor for granulocytic and monocytic differentiation [25], and inactivating mutations causing a block in granulocytic differentiation likely contribute to leukemogenesis. The prognosis of this genetic aberration in pediatric AML is still a matter of debate but generally, patients harboring this mutation are included in low/intermediate risk groups. Among the molecular lesions with an unfavorable prognosis, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) is a common gene involved in pediatric AML, whose frequency is age-related, being rare in infants and rising as age increases. FLT3 is essential for the proliferation, survival and differentiation of stem/progenitor cells. The most common type of mutation in FLT3 is represented by internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutations, but point mutations are also frequent, and both these lesions lead to the constitutive activation of this gene [26]. The WT1 gene is expressed in CD34+ hematopoietic stem progenitors and is crucial for the regulation of normal growth and development. Among pediatric AML cases, 15% are characterized by inactivating mutations of WT1 [21], and associated with a poor prognosis when FLT3-ITD mutations are also present [21]. Mutations in epigenetic regulators such as TET2, IDH1 and IDH2 are much less prevalent compared to adult AML, characterizing only 1–2% of pediatric patients [27], while signaling mutations such as NRAS, KRAS, CBL, GATA2, SETD2 and PTPN11 are more common in younger patients. Moreover, MYC alterations were identified as exclusive in children, suggesting different leukemogenesis mechanisms in children compared to adults [10][21].Nonetheless, therapies targeting alterations in these factors are showing promising results in adults, thus it is important to look for these lesions in pediatric cases too [27].

4. Clonal Evolution in Pediatric AML: From Diagnosis to Relapse

The concept of clonal evolution in cancer, which was first conceived in 1976 [28], appears to apply also to AML, as demonstrated by the pivotal work of Ding et al. [29] in adult AML and also confirmed in the pediatric setting [2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30]. This term refers to the selection and expansion, over the course of the disease, of subclones that originate from a common ancestral clone but acquire different mutations that confer them a survival advantage, leading to genetic diversity within a cell lineage [2]. AML arises from the accumulation of “early” DNA mutations in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), which enhance their self-renewal potential, leading to leukemia stem cells (LSCs). Additionally, “late” mutations that promote proliferation are necessary for the development of AML [31]. We can therefore identify “primary events” that are highly penetrant and stable during the course of the disease, and “secondary events” that occur later and only in some cells, leading to the development of different subclones and to a variation in the composition of cancer [2]. This explains the complexity of the determination of the proper treatment option, because of AML genomic heterogeneity not only at diagnosis, but also during therapy and eventually at relapse.

Several studies [2][30][32] have globally analyzed, by means of whole exome sequencing (WES), trios of pediatric AML diagnostic, remission and relapse specimens, in order to deeply characterize the key features that shapes clonal evolution over time. They showed that most of the dominant variants, which originate during ancestral leukemic development, persist from diagnosis to relapse, but many subclonal modifications, which develop later in specific subclones, do not, and thus, the genomic landscape at relapse also differs based on the use of different therapeutic agents [30]. They also demonstrated that, even if recurrent single mutations cannot be found, mutations in specific gene families are typical [30]. Indeed, aside from the canonical classification of AML, in terms of clonal evolution, we can further classify mutations into three major groups (Table 1):

Table 1. List of the main mutated genes, classified in three major groups, with the relative prominent occurrence in terms of timing (mainly at diagnosis and/or relapse).

| Group of Mutations | Genes | Timing |

|---|---|---|

| Cohesin complex genes | RAD21, SMC3, STAG2 | Diagnosis |

| ASXL1, ASXL2 | Diagnosis | |

| ASXL3 | Relapse | |

| BCOR, BCORL1, EZH2 | Diagnosis | |

| Signaling molecules | NRAS, CREBBP, KIT, FLT3-ITD | Relapse |

| PTPN11 | Diagnosis/relapse | |

| Others | SETD2, TYK2 | Diagnosis/relapse |

| SALL1 | Relapse | |

| C/EBPA | Diagnosis | |

| WT1 | Diagnosis/relapse |

- i.

-

Cohesin complex gene mutations;

- ii.

-

Transcription factors and epigenetic regulators mutations;

- iii.

-

Signaling molecules mutations.

Cohesin is a protein necessary for cell division, DNA repair and gene expression, and it is composed of four core subunits, three of which have been found to be mutated in pediatric AML, leading to a loss of cohesin function: RAD21, SMC3 and STAG2 [32]. Shiba et al. [32] demonstrated that variant allele frequencies (VAFs) of mutated SMC3 were high, suggesting these occur at an early stage of leukemogenesis.

Among the epigenetic regulators, mutations have been found in the Additional Sex combs-Like (ASXL) family, BCOR and BCORL1, EZH2. ASXL1 and ASXL2 mutations have been found in pediatric de novo AML, mainly in patients with t(8;21) [32], and an ASXL3 mutation has been described by Masetti et al. [2] at relapse (median frequency or MF of 29.7%), backtracking to a small subclone already present at diagnosis (MF of 0.3%). VAFs of mutated ASXL2 were lower than others, suggesting that this mutation is a secondary event. BCOR and its homologue BCORL1 suppress gene transcription through epigenetic mechanisms [32]. BCORL1 has been shown to be a tumor suppressor gene, and, as SMC3, BCORL1 appears to be mutated at an early stage in leukemic cells [32]. EZH2 is one of the most commonly mutated genes in pediatric Down syndrome AMKL, and it encodes for a subunit of a complex responsible for methylation [32].

Signaling pathway mutations include mutations of genes involved in Ras pathways such as NRAS, KRAS, PTPN11, and of tyrosine kinases such as KIT and FLT3. NRAS mutations have been found to be relapse specific, like those in CREBBP, a coactivator of several hematopoietic transcription factors [32]. Farrar et al. [30] described PTPN11 mutations, lost at relapse when they appeared as subclonal variants at diagnosis. Masetti et al. [2] found a PTPN11 mutation gained at relapse (MF of 31.9%), suggesting its role in increasing cell proliferation and/or survival. As previously described, FLT3 is essential for proliferation, survival and differentiation of stem/progenitor cells. Masetti et al. [2] showed that a small FLT3-TKD-mutated subclone present at diagnosis (MF of 3.4%) underwent expansion at relapse (MF of 13.3%), leading to increased cell proliferation and/or survival, and this mutation, together with NRAS and KIT mutations, was also described as a secondary event contributing to disease progression by Shiba et al. [32].

In addition, also genes that do not belong to these groups are frequently mutated. The previously described C/EBPA and WT1 mutations exhibit different patterns of recurrency in the study presented by Masetti et al. A highly penetrant biallelic mutation of C/EBPA was revealed, and in one patient, a homozygous non-frameshift insertion was present both at diagnosis and relapse in the majority of the tumor-cell population (MF > 80%). On the contrary, WT1 mutations appeared highly unstable, two different frameshift insertions were detected mainly at diagnosis (MF of 27.6% and 13.9), while a single-nucleotide variant was detected only at relapse (MF of 40%). SETD2 is a methyltransferase involved in the recruitment of mismatch repair (MMR) machinery, and its mutation results in a loss of function of the methyltransferase activity, leading to the build-up of several subclonal mutations and consequently, the increased plasticity and adaptability of leukemia cells, due to the failure of DNA repair [2]. A frameshift insertion of the SETD2 gene has been described both at diagnosis (MF of 32.5%) and at relapse (MF of 31.7%) [2]. The TYK2 gene is a member of the Janus tyrosine kinases (JAK) family involved in cell growth, differentiation and survival. Masetti et al. [2] found a mutation of TYK2 both at diagnosis (MF of 43%) and at relapse (MF of 14.9%), which causes a hyperactivation of the TYK2 pathway, resulting in aberrant cell survival through the upregulation of BCL2 (anti-apoptotic protein). SALL1 is a member of the transcriptional network that regulates stem cell pluripotency [33]; it has not been detected at diagnosis but only at relapse (MF of 28.6%) with a clone size at relapse of 50–60% (corrected for copy number variations) [2] (Table 1).

References

- Zwaan, C.M.; Kolb, E.A.; Reinhardt, D.; Abrahamsson, J.; Adachi, S.; Aplenc, R.; De Bont, E.S.J.M.; De Moerloose, B.; Dworzak, M.; Gibson, B.E.S.; et al. Collaborative efforts driving progress in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2949–2962.

- Masetti, R.; Castelli, I.; Astolfi, A.; Bertuccio, S.N.; Indio, V.; Togni, M.; Belotti, T.; Serravalle, S.; Tarantino, G.; Zecca, M.; et al. Genomic complexity and dynamics of clonal evolution in childhood acute myeloid leukemia studied with whole-exome sequencing. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 56746–56757.

- Masetti, R.; Vendemini, F.; Zama, D.; Biagi, C.; Pession, A.; Locatelli, F. Acute myeloid leukemia in infants: Biology and treatment. Front. Pediatr. 2015, 3.

- Pession, A.; Masetti, R.; Rizzari, C.; Putti, M.C.; Casale, F.; Fagioli, F.; Luciani, M.; Nigro, L.L.; Menna, G.; Micalizzi, C.; et al. Results of the AIEOP AML 2002/01 multicenter prospective trial for the treatment of children with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2013, 122, 170–178.

- Rasche, M.; Zimmermann, M.; Borschel, L.; Bourquin, J.-P.; Dworzak, M.; Klingebiel, T.; Lehrnbecher, T.; Creutzig, U.; Klusmann, J.-H.; Reinhardt, D. Successes and challenges in the treatment of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: A retrospective analysis of the AML-BFM trials from 1987 to 2012. Leukemia 2018, 32, 2167–2177.

- de Rooij, J.; Zwaan, C.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M. Pediatric AML: From biology to clinical management. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 4, 127–149.

- Clarke, R.T.; Bruel, A.V.D.; Bankhead, C.; Mitchell, C.D.; Phillips, B.; Thompson, M.J. Clinical presentation of childhood leukaemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2016, 101, 894–901.

- Locatelli, F.; Masetti, R.; Rondelli, R.; Zecca, M.; Fagioli, F.; Rovelli, A.; Messina, C.; Lanino, E.; Bertaina, A.; Favre, C.; et al. Outcome of children with high-risk acute myeloid leukemia given autologous or allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in the aieop AML-2002/01 study. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2015, 50, 2.

- Masetti, R.; Vendemini, F.; Zama, D.; Biagi, C.; Gasperini, P.; Pession, A. All-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of pediatric acute promyelocytic leukemia. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2012, 12.

- Testi, A.M.; Pession, A.; Diverio, D.; Grimwade, D.; Gibson, B.; De Azevedo, A.C.; Moran, L.; Leverger, G.; Elitzur, S.; Hasle, H.; et al. Risk-adapted treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia: Results from the International consortium for childhood APL. Blood 2018, 132, 405–412.

- Harrison, C.J.; Hills, R.K.; Moorman, A.V.; Grimwade, D.J.; Hann, I.; Webb, D.K.H.; Wheatley, K.; De Graaf, S.S.N.; Berg, E.V.D.; Burnett, A.K.; et al. Cytogenetics of Childhood acute myeloid leukemia: United Kingdom medical research council treatment trials AML 10 and 12. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 2674–2681.

- Creutzig, U.; Zimmermann, M.; Reinhardt, D.; Rasche, M.; von Neuhoff, C.; Alpermann, T.; Dworzak, M.; Perglerová, K.; Zemanova, Z.; Tchinda, J.; et al. Changes in cytogenetics and molecular genetics in acute myeloid leukemia from childhood to adult age groups. Cancer 2016, 122.

- Conneely, S.E.; Rau, R.E. The genomics of acute myeloid leukemia in children. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020, 39, 189–209.

- Lonetti, A.; Indio, V.; Laginestra, M.A.; Tarantino, G.; Chiarini, F.; Astolfi, A.; Bertuccio, S.N.; Martelli, A.M.; Locatelli, F.; Pession, A.; et al. Inhibition of methyltransferase DOT1L sensitizes to sorafenib treatment AML cells irrespective of MLL-rearrangements: A novel therapeutic strategy for pediatric AML. Cancers 2020, 12, 1972.

- Masetti, R.; Bertuccio, S.N.; Astolfi, A.; Chiarini, F.; Lonetti, A.; Indio, V.; De Luca, M.; Bandini, J.; Serravalle, S.; Franzoni, M.; et al. Hh/Gli antagonist in acute myeloid leukemia with CBFA2T3-GLIS2 fusion gene. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 26.

- Masetti, R.; Bertuccio, S.N.; Guidi, V.; Cerasi, S.; Lonetti, A.; Pession, A. Uncommon cytogenetic abnormalities identifying high-risk acute myeloid leukemia in children. Futur. Oncol. 2020, 16, 2747–2762.

- Masetti, R.; Bertuccio, S.N.; Pession, A.; Locatelli, F. CBFA2T3-GLIS2-positive acute myeloid leukaemia. A peculiar paediatric entity. Br. J. Haematol. 2018, 184, 337–347.

- Hara, Y.; Shiba, N.; Yamato, G.; Ohki, K.; Tabuchi, K.; Sotomatsu, M.; Tomizawa, D.; Kinoshita, A.; Arakawa, H.; Saito, A.M.; et al. Patients aged less than 3 years with acute myeloid leukaemia characterize a molecularly and clinically distinct subgroup. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 188, 528–539.

- De Rooij, J.D.E.; Branstetter, C.; Ma, J.; Li, Y.; Walsh, M.P.; Cheng, J.; Obulkasim, A.; Dang, J.; Easton, J.; Verboon, L.J.; et al. Pediatric non–down syndrome acute megakaryoblastic leukemia is characterized by distinct genomic subsets with varying outcomes. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 451–456.

- Malinge, S.; Izraeli, S.; Crispino, J.D. Insights into the manifestations, outcomes, and mechanisms of leukemogenesis in Down syndrome. Blood 2009, 113, 2619–2628.

- Bolouri, H.; Farrar, J.E.; Triche, T.; Ries, R.E.; Lim, E.L.; Alonzo, T.A.; Ma, Y.; Moore, R.; Mungall, A.J.; Marra, M.A.; et al. The molecular landscape of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia reveals recurrent structural alterations and age-specific mutational interactions. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 103–112.

- Sandahl, J.D.; Coenen, E.A.; Forestier, E.; Harbott, J.; Johansson, B.; Kerndrup, G.; Adachi, S.; Auvrignon, A.; Beverloo, H.B.; Cayuela, J.-M.; et al. t(6;9)(p22;q34)/DEK-NUP214-rearranged pediatric myeloid leukemia: An international study of 62 patients. Haematologica 2014, 99, 865–872.

- Cazzaniga, G.; Dell’Oro, M.G.; Mecucci, C.; Giarin, E.; Masetti, R.; Rossi, V.; Locatelli, F.; Martelli, M.F.; Basso, G.; Pession, A.; et al. Nucleophosmin mutations in childhood acute myelogenous leukemia with normal karyotype. Blood 2005, 106, 1419–1422.

- Brunetti, L.; Gundry, M.C.; Sorcini, D.; Guzman, A.G.; Huang, Y.H.; Ramabadran, R.; Gionfriddo, I.; Mezzasoma, F.; Milano, F.; Nabet, B.; et al. Mutant NPM1 maintains the leukemic state through HOX expression. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 499–512.e9.

- Leroy, H.; Roumier, C.; Huyghe, P.; Biggio, V.; Fenaux, P.; Preudhomme, C. CEBPA point mutations in hematological malignancies. Leukemia 2005, 19, 329–334.

- Sexauer, A.N.; Tasian, S.K. Targeting FLT3 signaling in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 248.

- Rasche, M.; Von Neuhoff, C.; Dworzak, M.; Bourquin, J.-P.; Bradtke, J.; Göhring, G.; Escherich, G.; Fleischhack, G.; Graf, N.; Gruhn, B.; et al. Genotype-outcome correlations in pediatric AML: The impact of a monosomal karyotype in trial AML-BFM 2004. Leukemia 2017, 31, 2807–2814.

- Aparicio, S.; Caldas, C. The implications of clonal genome evolution for cancer medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 842–851.

- Ding, L.; Ley, T.; Larson, D.E.; Miller, C.A.; Koboldt, D.C.; Welch, J.S.; Ritchey, J.K.; Young, M.A.; Lamprecht, T.; McLellan, M.D.; et al. Clonal evolution in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature 2012, 481, 506–510.

- Farrar, J.E.; Schuback, H.L.; Ries, R.E.; Wai, D.; Hampton, O.A.; Trevino, L.R.; Alonzo, T.A.; Auvil, J.M.G.; Davidsen, T.M.; Gesuwan, P.; et al. Genomic profiling of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia reveals a changing mutational landscape from disease diagnosis to relapse. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2197–2205.

- Vetrie, D.; Helgason, G.V.; Copland, M. The leukaemia stem cell: Similarities, differences and clinical prospects in CML and AML. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 158–173.

- Shiba, N.; Yoshida, K.; Shiraishi, Y.; Okuno, Y.; Yamato, G.; Hara, Y.; Nagata, Y.; Chiba, K.; Tanaka, H.; Terui, K.; et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals the spectrum of gene mutations and the clonal evolution patterns in paediatric acute myeloid leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 175, 476–489.

- Salman, H.; Shuai, X.; Nguyen-Lefebvre, A.T.; Giri, B.; Ren, M.; Rauchman, M.; Robbins, L.; Hou, W.; Korkaya, H.; Ma, Y. SALL1 expression in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7442–7452.

More

Information

Subjects:

Oncology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

580

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

23 Jun 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No