| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dirk Reinhardt | + 5159 word(s) | 5159 | 2021-05-12 11:56:32 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 5159 | 2021-05-13 03:23:41 | | |

Video Upload Options

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a malignant, hematologic disease that accounts for about one-fifth of all childhood leukemia cases.

1. Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a malignant, hematologic disease that accounts for about one-fifth of all childhood leukemia cases. In recent decades, the prognosis of AML patients has improved thanks to advances in distinct diagnostic and therapeutic tools. Although the vast majority of children initially achieve complete remission, overall long-term survival is still limited by refractory disease and relapse, which occur in about one-third of children with AML and are linked to poor prognosis [1][2]. To date, therapy is risk-adapted but still mainly based on chemotherapeutic schemes associated with systemic toxicity. Therefore, innovative and selective therapeutic approaches with greater efficacy are urgently needed. To identify suitable, promising therapeutic targets, fundamental knowledge about leukemogenesis in AML is required.

Originating from uncontrolled proliferating immature myeloid precursor cells at different stages of maturation, the pathogenesis of AML is mainly localized in bone marrow, the major hematopoietic tissue. Physiologically, bone marrow represents a highly regenerative tissue that ensures continuous replenishment of hematopoietic cells originating from a common hematopoietic stem cell (HSC). Because the lifespan of differentiated blood cells in peripheral vessels is limited, each multipotent HSC gives rise to approximately 5 × 1011 cells each day, making the hematopoietic system one of the most regenerative tissues in humans [3]. Various cellular and non-cellular factors in the bone marrow microenvironment (BMM) tightly regulate this process, emphasizing the high impact of the hematopoietic microenvironment. In humans, the hematopoietic system is considered to be one of the first developing functional systems, and its localization changes throughout ontogeny. In early embryogenesis, the first hematopoietic cells are assumed to arise from the yolk sac until the second wave of hematopoiesis occurs dorsally of the aorta (referred to as the aorta–gonad–mesonephros region) (reviewed in [4]). Definitive HSCs then move to the fetal liver, which enables rapid expansion of these highly proliferative cells [5][6]. Shortly before birth, HSCs colonize the bone marrow cavity, which becomes the final hematopoietic microenvironment (BMM) [4].

Whilst hosting hematopoietic cells under healthy conditions, in leukemogenesis, this BMM is taken over by malignantly transformed and uncontrollably proliferating leukemic blasts. As these cells outcompete healthy hematopoiesis, the typical clinical presentation arises.

In analogy to the hierarchical order of healthy hematopoiesis, leukemic blasts are thought to arise from a leukemic stem cell (LSC) population that is phenotypically identified as CD34+CD38- and functionally defined by the stem cell-like properties of infinite self-renewal and leukemia engraftment in a patient-derived xenograft model [7][8]. It is noteworthy that, in immunodeficient xenotransplant models, functional LSCs have also been detected within the CD34+CD38+ fraction in AML, depending on the mouse strain, indicating that the LSC population is more heterogenous than previously suggested [9][10]. In this regard, LSCs are also referred to as leukemia-initiating or propagating cells, emphasizing their importance as the putative origin of leukemogenesis [7].

High-yielding, single-cell analyses indicate that in leukemia evolution, the acquisition of various genetic mutations leads to a complex pattern of genetically heterogenous leukemic subclones that can be either competitive or cooperative [11]. During the course of disease, environmental factors in bone marrow exert a selective pressure on leukemic cells, thereby remodeling clonal evolution [12][13]. Genetic diversity is presumed to enable the selection of resistant leukemic subclones, which in turn, could promote the evolution of relapsed and refractory disease [13].

In addition to cell-intrinsic genetic dysregulation, numerous studies have demonstrated that microenvironmental components in malignantly altered bone marrow critically impact leukemogenesis in AML (summarized in [14][15][16]). Leukemic blasts, and their neighboring microenvironmental components, seem to mutually influence each other in a bidirectional manner via complex, modified interacting pathways [16][17]. Although this is reminiscent of healthy hematopoiesis, in AML the architecture and function of the microenvironment importantly differ from those in health. In the pathological microenvironment, the altered release of mediators as well as deviating intercellular contacts lead to the formation of a malignantly modified leukemic niche that disturbs physiological hematopoiesis but fosters leukemia maintenance, thus enabling leukemia progression [17][18][19].

On the one hand, there are indications that certain changes in non-hematopoietic stromal cells may precede and, in turn, promote leukemia development [20]. On the other hand, leukemic blasts are assumed to modify the formerly healthy hematopoietic bone marrow niche to their favor, at the expense of healthy blood formation [21][22][23].

Therefore, targeting critical cellular and non-cellular interactions in the altered leukemic microenvironment could be a promising approach for achieving the major objective of establishing more effective and safer therapies that efficiently eliminate AML blasts. Redirecting this leukemia-supporting niche into a healthy hematopoietic microenvironment will require sound and comprehensive knowledge about the physiological and pathological processes in the BMM.

2. Hematopoietic Cells and Their Microenvironment

Physiologically, hematopoietic cells develop in a highly specialized and supportive microenvironment. As this BMM ensures lifelong continuous replenishment of the blood system, it must be tightly regulated by surrounding cellular and non-cellular elements. These microenvironmental components are constantly interconnected with each other and with hematopoietic cells, providing optimal conditions to direct HSC fate. In this context, an analogy to the “seed-and-soil” theory has been drawn: The BMM serves as fertile soil providing optimal conditions for the maturation of HSCs, which represent the seeds in the soil (summarized in [24]). As early as 1978, the first reports were published regarding the significance of specific bone marrow regions to hematopoiesis, originally referred to as the stem cell niche [25]. Based on the different structural and functional aspects of these different regions within the BMM, distinctions between different niches have been established [26]. Whereas the endosteal niche primarily consists of osteolineage cells, the perivascular niche comprises disparate sub-niches, depending on certain vascular subtypes with associated endothelial and perivascular cells (Figure 1).

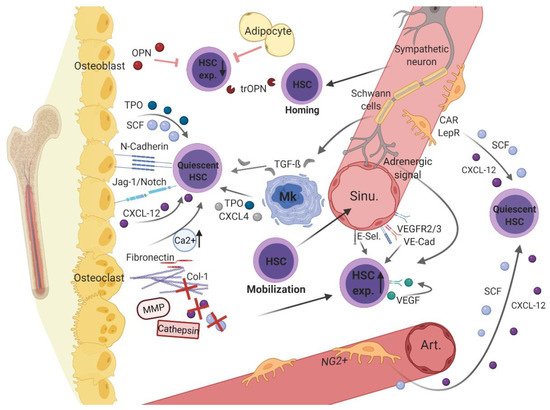

Figure 1. Healthy hematopoietic bone marrow microenvironment.

Endosteal and vascular niches within the BMM consist of different hematopoietic cells (i.e., hematopoietic stem cell [HSCs] and megakaryocytes [MK]) as well as non-hematopoietic cells (e.g., osteoblasts, osteoclasts, adipocytes, sympathetic neurons with associated Schwann’s cells, distinct perivascular stromal cells [neural-glia-2 (NG2+)], C-X-C motif chemokine [CXCL]-12 abundant reticular [CAR] cells, leptin-receptor-positive [LepR+] cells, and endothelial cells) and structural components (i.e., arterioles [Art.], sinusoidal vessels [sinu.], fibronectin, collagen [Col]-1, calcium [Ca2+], and the enzymes cathepsin and matrix metalloproteinase [MMP]). Various non-cellular factors (e.g., osteopontin [OPN], thrombin cleaved OPN [trOPN], and stem cell factor [SCF)), C-X-C motif chemokine [CXCL]-12, CXCL-4, transforming growth factor beta [TGF-β], vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF], and vascular endothelial cadherin [VE-Cad], thrombopoietin [TPO], Notch, and its ligand Jagged-1) expressed by the cellular components contribute to hematopoietic regulation in the BMM. Figure 1 was created with biorender.com (accessed on 13 February 2021).

2.1. Endosteal, Osteoblastic Niche Regulates Hematopoiesis

Since primitive HSCs have first been isolated from the inner bone surface, close to osteolineage cells, the endosteal region was identified as the HSC niche [27][28]. As this niche mainly consists of osteolineage cells, its importance for the regulation of HSC fate was later confirmed. Osteoblastic cells have been shown to ensure long-term maintenance of hematopoiesis by regulating quiescence in long-term (LT)-HSCs [29][30][31][32]. This form of hematopoietic cell control is mediated by various ways of direct and indirect cellular interplay.

In different mouse models, parathyroid-hormone signaling and lack of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) receptor-1A stimulated osteoblastic cells, which in turn increased HSC numbers through Notch ligand Jagged-1- or N-cadherin-mediated cell adhesion to HSCs, respectively [31][33]. Further studies also revealed that osteoblasts essentially contribute to HSC quiescence and maintenance through N-cadherin [34][35]. However, in genetically modified mice, conditional deletion of N-cadherin revealed no significant effect on HSC function and number, suggesting that HSC quiescence may be partly influenced by but not fully dependent on this cellular interaction [36][37]. Moreover, osteoblasts promote stem cell quiescence and long-term maintenance by secretion of various soluble mediators, such as by thrombopoietin (TPO) [38][39], stem cell factor (SCF, also termed steel factor or kit-ligand) [40][41], and C-X-C motif chemokine 12 (CXCL-12) [42][43]. The latter is also considered the strongest chemotactic factor that acts on HSCs via CXCR-4, promoting recirculation of hematopoietic cells to the endosteal region [44]. Nonetheless, these factors appear to be dispensable or at least balanced by other signaling mechanisms, since deletion of CXCL-12 and SCF does not significantly compromise HSC numbers in vivo [45][46]. Moreover, osteoblasts contribute to mineralization by producing extracellular matrix (ECM) components such as collagen-1 or fibronectin [47]. The ECM protein osteopontin (OPN) has been shown to negatively regulate HSC pool size [48]. Its thrombin-cleaved form, which is found predominantly in the BMM, serves as a chemoattractant, mediating the migration and quiescence of HSCs and progenitor cells through interaction with the alpha(9)beta(1) and alpha(4)beta(1) integrins [49]. As recently been shown by Cao et al., OPN already plays a pivotal role in the fetal and newborn hematopoietic BMM (not in liver) [50]. The mentioned endosteal niche factors are cleaved by proteolytic enzymes (i.e., cathepsin-K and matrix metalloproteinase [MMP]-9) secreted by activated, bone-resorbing osteoclasts, leading to mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells [51]. Conversely, via osseous remodeling processes, osteoclasts cause an increase in the calcium level, which is proposed to protect quiescent HSCs through calcium-sensitive receptors [52]. In addition, bone damage has been revealed to promote HSC expansion [53], and a recent imaging study spatially allocated expanding HSCs in areas with high bone turnover [54]. Therefore, in addition to osteoblasts, osteoclasts act as noteworthy cellular components in balancing hematopoietic processes within the endosteal niche. However, distinct endosteal components and associated processes were found to be dispensable, questioning the impact of this endosteal niche in regulating hematopoiesis in the healthy BMM [37][45][55][56][57][58]. Consistently, in vivo investigations revealed that a minority of hematopoietic cells are localized close to the endosteal bone surface, but the majority are localized in the perivascular region within the BM cavity [45][59].

2.2. Perivascular Niches Regulate Hematopoiesis

The BMM is traversed by an intricate vascular system consisting of arterioles that adjoin the endosteum and branches, creating an intricate venous–sinusoidal network in the central bone cavity [60]. Recently, another vascular subtype was reported to connect sinusoids to arterioles in a transition zone, which has been attributed to the endosteal area rather than the central bone marrow [61]. The vast majority of hematopoietic cells have been shown to reside in the perivascular bone marrow region [43][45][59]. This niche can be sub-divided according to distinct types of vessels, which can be assigned to certain perivascular stromal cells [62] and endothelial cells (ECs) [61][63][64], forming different perivascular sub-niches critical for hematopoietic regulation in the BMM [65][66][67].

In the perisinusoidal niche, CXCL-12-abundant reticular (CAR) and leptin-receptor-positive (LepR+) cells direct the mobilization and maintenance of HSCs expressing high amounts of CXCL-12 and SCF [43][45][68]. Of note, in vivo studies revealed that HSC maintenance is necessarily regulated by SCF from LepR+ cells, whereas CXCL-12–mediated regulation by CAR and LepR+ cells appears to be dispensable [45][58].

In vivo imaging identified different subpopulations of stromal cells characterized by green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression under the control of the nestin promoter (Nes-GFP) [62]. Whereas nestin-dim stromal cells largely overlap with CAR and LepR+ cells in the perisinusoidal region, periarteriolar nestin-bright cells are reported to comprise neural-glia-2 (NG2+)-expressing cells [65]. Both contribute to the protection of HSC quiescence mainly conferred by CXCL-12 and SCF secretion [45][65].

In addition to mesenchymal-derived stromal cells, ECs serve as critical sources of regulatory niche factors and importantly contribute to hematopoietic regulation [45][58]. Given the heterogeneity of the EC population, these cells include sinusoidal-derived ECs (low expression of CD31 and Endomucin [type L] [61]) and arteriolar ECs (high expression of CD31 and Endomucin [type H]) [61][66]. Arteriolar and artery-derived ECs have been found to more abundantly express the key niche factors CXCL-12 and SCF [64]. Among ECs, arteriolar ECs are reported to almost exclusively produce SCF and thus importantly regulate HSC maintenance, whereas sinusoidal ECs expressing SCF appear dispensable [69]. When compared with sinusoidal and capillary/arteriole-derived ECs, a recently defined sca+ and vwf+ arterial EC subset has been shown to more abundantly express SCF [64], thereby representing an apparently relevant regulatory EC subset in the BMM.

Sinusoidal ECs are known to importantly contribute to the niche-dependent HSC regulation through vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors 2 and 3 [70][71]. This angiogenic factor (VEGF) supports the proliferation and survival of HSCs by binding to its same-named receptor (VEGFR) in an autocrine manner [72]. In vivo examination provided evidence of VEGFR2-mediated reconstitution of sinusoidal ECs, which essentially promoted regeneration and engraftment of HSCs post-transplantation [70].

Conditional deletion of VEGF-C in endothelial and stromal cells leads to decreased hematopoietic cell and niche regeneration. Conversely, exogenous administration of VEGF-C leads to improved hematopoietic niche recovery after irradiation, suggesting that VEGF is important for maintaining the HSC niche [73]. Adhesion to E-selectin, an adhesion molecule that is constitutively expressed on sinusoidal ECs, promotes HSC proliferation and activation, to the detriment of self-renewal and quiescence [74][75].

In the perisinusoidal region, a major subset of megakaryocytes is reported to positively direct HSC quiescence and maintenance by expression of mediators such as CXCL-4, TPO, and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β)1 [76][77][78]. As part of the TGF-β superfamily, TGF-β1 functions as a pleiotropic mediator, importantly shifting the balance between HSC quiescence and proliferation in favor of the former [79][80]. To exert this regulatory function, the secreted latent form of TGF-β must first be activated by different cellular and non-cellular mechanisms in the BMM.

As the hematopoietic BMM is vastly innervated and controlled by the sympathetic nervous system [81], non-myelinating Schwann’s glial cells wrapping peripheral nerve fibers maintain the quiescent HSC pool by activating latent TGF-β [82]. However, it has been suggested that high levels of catecholaminergic transmitters stimulate HSC proliferation and mobilization [83][84]. Moreover, the circadian release of hematopoietic progenitor cells through β-adrenergic signals was shown to be promoted by neural cells of the sympathetic nervous system, induced by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) [85][86].

A relevant subset of adipocytes localized in the perisinusoidal region has been recently identified as sympathetically innervated and regulated [87]. Initially, adipocytes were preliminarily believed to exert a negative influence on hematopoiesis [88]. Concordantly, in vivo studies revealed that inhibition of adipogenesis following chemotherapy-induced ablation leads to an improved regeneration of hematopoiesis [89]. However, adipocytes have been found to support hematopoietic regeneration through secretion of SCF [90] and to positively contribute to hematopoiesis through the adipokines leptin and adiponectin [91][92]. In addition, in a genetically modified mouse model, a complete lack of adipocytes led to markedly increased extramedullary hematopoiesis and alteration in CXCL-12/CXCR-4 signaling [93]. These results suggest that adipocytes are required for appropriate hematopoietic regulation in BMM. As CD169+ macrophages stimulate secretion of the retention factor CXCL-12 by periarteriolar Nes-GFP+ stromal cells, they presumably contribute to the maintenance of HSC quiescence [94].

The above-discussed results, in part, are indicative of the idea of a vascular sub-niche that plays a binary role within the hematopoietic BMM. Whereas periarteriolar localized parts seem to rather protect the quiescent HSC pool [65][95], perisinusoidal niche cells may be more likely to promote the expansion, differentiation, and mobilization of actively circulating HSCs [65][66][70]. It, therefore, seems reasonable to assume that structurally and functionally separated perivascular sub-niches broadly guarantee differential regulation of distinct hematopoietic cell subsets [95]. However, a strict distinction between these specialized sub-niches appears controversial due to anatomical and functional overlaps between these niches and has therefore not been clearly defined [59]. In addition, contrary to the long-held belief that the hematopoietic BMM consists of different niches, an increasingly accepted point of view states the existence of only one niche, comprising a periarteriolar and a perisinusoidal compartment [96]. Further research is necessary to fully elucidate the exact localization of HSCs at different stages in bone marrow niches and to clarify the specific regulatory functions of distinct niches in the direction of hematopoiesis.

2.3. Hypoxia in the Bone Marrow Microenvironment

Despite its pronounced vascularization, the BMM has been revealed to be hypoxic [97], with varying oxygen (O2) levels reported to range from 0.1% and 6% in different areas within the bone marrow [98][99]. In this hypoxic microenvironment, hematopoietic cells present a hypoxic profile, regardless of their location and cell cycle status, characterized by intracellular incorporated pimonidazole and upregulation of the transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α [60][100][101]. Under hypoxic conditions, HIF-1α shows full transcriptional activities and has been proposed to necessarily contribute to the activation of an anaerobic glycolytic metabolic program in quiescent HSCs [100][102][103]. Hypoxic HSCs sustain their own stem cell properties through the stable expression of HIF-1α, which essentially regulates stem cell survival and quiescence [100]. In this regard, several studies also have suggested that hypoxia contributes to hematopoietic regulation in bone marrow (reviewed in [104]).

Based on indirect measurements, the endosteal niche has long been believed to be comparatively hypoxic, which was thought to support the maintenance of HSCs and subsequently influence the distribution of HSCs in the BMM [105]. However, direct in vivo measurements showed that the total extravascular oxygen tension (pO2) is significantly higher in endosteal regions compared to the local pO2 in the vicinity of nestin-negative vessels, with the lowest level found in the deeper perisinusoidal region (1.3% O2) [97]. More recently, O2 values measured in areas around HSCs and more differentiated HPCs were very similar [54]. This may suggest a lower impact of different levels of hypoxia on the microenvironmental regulation of hematopoiesis and may correspond to a dense arteriolar network, which has been found to abundantly enclose the endosteal surface [65][106].

The exact oxygen concentrations within different niches, as well as the detailed impacts on hematopoietic regulation, remain elusive and are the subject of current research studies.

3. Dysregulated Leukemic Bone Marrow Microenvironment

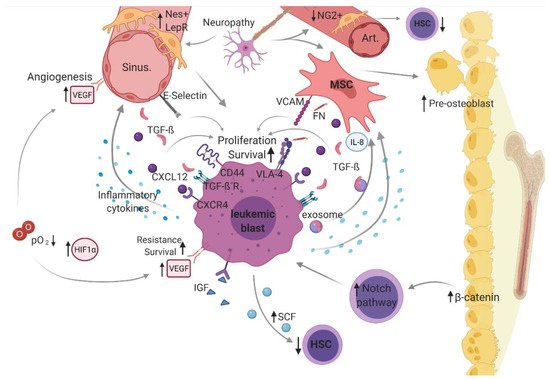

In leukemogenesis, the bone marrow is typically characterized by increased infiltration of uncontrollably proliferating leukemic cells (blasts) at the expanse of healthy hematopoiesis. It has been shown that disturbed cell-intrinsic regulation of leukemic cells is accompanied by deregulation of the bone marrow niche, suggesting a decisive role of an altered BMM in leukemogenesis (Figure 2). Of note, various studies have indicated that this malignant BMM also favors leukemogenesis by promoting immune-evading mechanisms (reviewed in Sendker et al.) [107].

Figure 2. Leukemic bone marrow microenvironment.

The idea of a transformed microenvironment facilitating the development of hematopoietic malignancies was reported first by Dührsen and Hossfeld in 1996 [108]. Since then, several studies have investigated the malignant microenvironment. However, the exact role and contribution of the microenvironment in leukemogenesis have not yet been fully clarified. Understanding the cellular crosstalk in the leukemic microenvironment as well as its contribution to the initiation, progression, relapse, and refractoriness of AML is critical for the identification of promising therapeutic targets.

In a malignantly altered BMM, dysregulated cellular (i.e., mesenchymal stem cell [MSCs], osteoblasts, hematopoietic stem cells [HSC], sympathetic neurons, distinct perivascular stroma cells [neural-glia-2 (NG2+)], C-X-C motif chemokine [CXCL]-12 abundant reticular [CAR] cells, leptin-receptor-positive [LepR+] cells, and endothelial cells) and structural components (i.e., arterioles [Art], sinusoidal vessels [sinu], fibronectin [FN], and oxygen level [O2]) as well as non-cellular mediators (stem cell factor [SCF], CXCL-12, transforming growth factor beta [TGF-β], vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF] and vascular endothelial cadherin [VE-Cad], thrombopoietin [TPO], and hypoxia-inducible factor [HIF]-1α), including related cellular interaction and signaling (vascular cell adhesion molecule [VCAM)]-1 and very late antigen [VLA)-4), constitute a supportive niche for leukemic blasts, driving pathogenesis and disease progression in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Figure 2 was created with biorender.com (accessed on 13 February 2021).

3.1. Microenvironment-Mediated Malignancy Versus Malignancy-Mediated Microenvironment

In the leukemic microenvironment, dysregulations not only occur in hematopoietic cells but also in non-hematopoietic cells. This raises the question of what is first in leukemogenesis?

In non-hematopoietic stromal cells derived from patients with AML and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), certain non-clonal (epi-)genetic aberrations have been revealed and differ from mutations found in hematopoietic cells [20][109][110]. These results may indicate a pivotal role of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in mediating leukemogenesis but do not answer the question of whether microenvironmental stromal cells facilitate disease progression rather than initiation. In mouse models, activating β-catenin mutation in osteoblasts cooperates with Foxo-1 to lead to AML development via activation of the NOTCH pathway in HSCs, which is suggestive of an initiative role of microenvironmental cells [111][112]. However, in an in vitro investigation, leukemic MSCs did not necessarily contribute to the leukemic process, although these stromal cells displayed altered phenotypic and functional features linked to the progression of leukemogenesis [113].

In contrast, multiple reports indicate that donor-derived leukemia following allogenic stem cell transplantation for different hematopoietic malignancies (reviewed by [114]) is a powerful in vivo model, suggesting that the malignant microenvironment pressures healthy donor-derived HSCs to convert into leukemic cells [114][115]. These examples favor an initiative role of the microenvironment preceding leukemic clonal transformation. Interestingly, examples of donor-derived ALL and AML were also reported post-transplantation for beta-thalassemia in a 5 year old boy [116] and for aplastic anemia in a 12 year old girl, respectively [117]. Together with the finding that a relatively small proportion (about 5%) of all post-transplantation cases of leukemia relapse originates from donor cells [118][119] and most cases relapse as acute leukemia, these observations could indicate a type of hereditary leukemic predisposition mediated by the microenvironment [114].

Contrary to the concept of a transformed microenvironment that drives leukemia according to microenvironment-mediated malignancy, an opposite but not exclusive notion assumes malignant hematopoietic cells mediate malignancy-associated changes in the microenvironment (malignancy-mediated microenvironment), as MDS cells have been shown to induce malignant/MDS-like transformation in healthy MSCs [120]. Similarly, AML-derived conditioned medium has been shown to convey leukemic alteration (regarding repressed osteogenic differentiation and proliferation) in healthy MSCs, suggesting leukemic dysregulation is instructed by leukemic cells [22].

In in vivo AML models, LSCs lead to transcriptional changes in healthy MSCs, affecting the expression of various molecular mediators involved in intercellular crosstalk [121]. Interestingly, among these distinct MSCs, a heterogenous pattern of genetic alteration has been shown and linked to a heterogeneous prognosis, presumably reflecting the clinical heterogeneity of AML [121]. A recent study involving co-culture experiments revealed that AML-derived exosomes promote interleukin (IL)-8 secretion in co-cultured stromal cells, which in turn may contribute to leukemic self-protection from chemotherapy [122]. Similarly, further studies demonstrated that AML cells convey microenvironmental disruption through the production of exosomes and vesicles (i.e., affecting stromal cell metabolism or suppressing the natural killer [NK]-cell-mediated immune response) [21][123][124].

These results suggest that leukemic cells differentially remodel the previously healthy microenvironment to their favor, indicative of a secondary induced malignant microenvironment that may further support disease progression. In this context, microenvironmental-mediated malignancy and malignancy-mediated microenvironment do not seem to mutually exclude each other, but rather to complementarily cooperate in a bidirectional manner, favoring hematopoietic insufficiency and leukemogenesis.

3.2. Bidirectional Interplay in a Leukemic Microenvironment

Numerous studies point to a self-reinforcing, bidirectional interplay between leukemic cells and their microenvironment that favors further disease progression (reviewed in Korn et al. 2017 [125]) and resembles a vicious cycle. In the pathological microenvironment, changes in the release of soluble mediators, such as proinflammatory cytokines, and deviating inter-cellular contacts lead to the formation of a leukemic niche at the expense of healthy hematopoiesis.

The retention of LSCs in the leukemic bone marrow niche depends on cellular interactions, which are mediated by CXCR-4/CXCL-12 signaling and other pathways. In addition, AML blasts secrete high amounts of SCF, a retention factor, that importantly attracts HSCs into less suitable areas within the leukemic BMM, from where they can only be mobilized with difficulty, which serves to impede healthy hematopoiesis [14].

Malignant, leukemic cells express certain adhesion molecules to an increased extent, such as CD44, that interact with ECs expressing E-selectin, resulting in promoted chemoresistance and upregulated viability and proliferative capacity [74]. The cellular crosstalk between vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 on MSCs and very late antigen (VLA)-4 (an integrin alpha4βeta1 heterodimer) on leukemic cells is reported to lead to transcriptional changes in stromal bone marrow-derived cells, causing upregulation of distinct nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) target genes and ultimately having a beneficial effect on leukemic cell growth, survival, and chemoresistance [126]. The interaction between VLA-4–expressing AML cells with fibronectin on MSCs has been correlated with adverse outcomes and recurrence in AML, as this interplay causes increased drug resistance mediated by intracellular activation of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI-3K)/AKT/Bcl-2 pathway [127].

Leukemic cells increasingly produce several proinflammatory cytokines, such as Il-1 that induce surrounding ECs and stromal cells to secrete growth factors such as CXCL-12 or colony-stimulating factors, which are proposed to result in unlimited cell growth and proliferation of leukemic blasts [128]. In pediatric AML patient samples, inhibition of BMP (a molecule that belongs to the TGF-ß superfamily) using the BMP-inhibitor K02288 promoted differentiation of LSCs, while reducing viability and colony counts in vitro, suggesting the significance of the BMP-Smad pathway in pediatric AML [129].

Despite the healthy microenvironment, TGF-β restricts hematopoietic proliferation, and in the leukemic microenvironment, TGF-β has also been implicated in leukemogenesis [130]. In this regard, TGF-β has been shown to protect leukemic blasts from lethal chemotherapeutic effects and favor quiescence in LSCs, thus promoting leukemic progression [131]. Moreover, TGF-β importantly contributes to leukemia progression by dysregulating the leukemic microenvironment [132]. Whilst elevated TGF-β levels have been observed in the AML BMM [133][134], predominantly upon release by megakaryocytes (MKs) and to a lesser extent by ECs [135], other studies reported decreased TGF-β levels in AML patients’ sera [136]. However, as shown by multiple studies, TGF-β1 importantly contributes to leukemogenesis [130][132][137]. The BMM in children with Down syndrome (DS)-acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AMKL) is characterized by marrow fibrosis [138][139], and TGF-β has been revealed as the main mediator of bone marrow fibrosis [140]. Based on pediatric patient-derived samples, Hack et al. showed that TGF-β supports fibrosis and thus significantly contributes to leukemogenesis in pediatric DS-AMKL [141].

Given that MKs and leukemic blasts abundantly express TGF-β, resulting in markedly increased TGF-β levels in the DS-AMKL BMM, and TGF-β has been shown to induce early-stage marrow fibrosis in DS-AMKL [141], TGF-β appears to play a pivotal role in the leukemogenesis of AMKL (FAB-M7) in children with and without trisomy-21. Exosomes released in AML have been revealed to contain high concentrations of TGF-β and to impact leukemogenesis and the therapeutic response [134][142]. Thereby, through secretion of exosomes, leukemic blasts remodel their environment into a leukemia-favoring niche, protecting AML blasts [21][123][143].

In AML, insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 and its same-named receptor IFG-R1 significantly contribute to leukemogenesis, according to evidence that IGF-1/IGF-1R signaling exerts pro-leukemic effects on AML cells in vitro via activation of downstream PI3K/Akt and the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk) pathways [144][145]. In the DS-AMKL mice model, overactive IGF/IGF1R-signaling, cooperatively with the mutated lineage determining transcription factor GATA1 contribute to malignant transformation of GATA1-short mutation bearing fetal megakaryocytic progenitors, suggesting a developmental stage-specific interplay in fetal megakaryopoiesis [146]. In AML samples, increased levels of IGF-1 and associated binding proteins (IGF-BP) were shown to correlate with prognosis, which leads to the assumption that these markers have the potential to serve as predictive tools for tracing residual disease load [147]. In contrast to the stated pro-leukemic role of IGF-BP-1–6, IGF-BP-7 has a tumor-suppressive role in leukemogenesis [148].

In an MLL-AF9 AML model, it was demonstrated that leukemic infiltration leads to sympathetic neuropathy, which is presumably due to damaged β-adrenergic signaling and includes disruption of quiescent perisinusoidal nestin-positive cells, resulting in an impaired physiological niche function with reduced HSC-maintaining NG2+ periarteriolar cells but increased leukemia-supportive pericytes [149]. This process is accompanied by increased expansion of MSCs and progenitor cells, primed for osteogenic differentiation (limited to osteoprogenitor cells) [149]. In line with the latter, Battula et al. described a pre-osteoblast-rich niche that further favors the expansion of leukemic blasts [150].

In patient-derived AML cells, VEGF and its receptor VEGFR2 have been reported to be overexpressed [151] and associated with a poor prognosis in AML [152]. The angiogenic factor VEGF-C is proposed to increase the proliferation and survival of leukemic blasts while protecting them from pro-apoptotic signals [153]. Accordingly, in pediatric patient-derived AML samples, increased endogenous levels of VEGF-C were significantly linked to reduced blast elimination, reflected by increased drug resistance in vitro and higher blast count on day 15 as well as a longer time to complete remission in-vivo [154]. VEGF is promoted by hypoxia in normal and malignant cells [155]. Notably, a correlation between the hypoxia marker HIF1α and VEGF-A has been recently reported. Both are overexpressed in AML cells, but the concentration of HIF1α was significantly higher in AML-M3-derived cells than in other AML cells [156]. This could be explained by the oncogenic mutation PML-RARA in promyelocytic leukemia (M3) [157].

Hypoxia-mediated signaling through the transcription factor HIF-1α is required for the maintenance of leukemia-initiating cells in vitro [158] and in vivo [159], suggesting a pivotal role for hypoxia in sustaining leukemia. Furthermore, hypoxia promotes the recruitment of leukemic blasts expressing more CXCR-4 under hypoxic conditions through increased HIF-1α levels [160]. In addition, hypoxia not only conveys anti-apoptotic and pro-proliferative effects on leukemic blasts but also may contribute to chemoresistance [161]. In a patient-derived xenograft model (with knockdown of MIF, HIF-1α, and HIF-2α), leukemia cell proliferation was promoted by hypoxia and HIF-1α. This subsequently caused constitutive overexpression of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in AML blasts, which in turn stimulated Il-8 expression, conferring leukemic growth and a survival advantage [162][163]. Contrary to the notion that hypoxia is a major contributor to leukemia progression, HIF-1α is also considered to have a suppressive function in leukemogenesis [164].

Though most results favor a pro-leukemic role, indicative of a highly hypoxic leukemic microenvironment, the oxygen content in AML-derived bone marrow samples is approximately as high as the pO2 in physiological bone marrow samples (46.05 mmHg [6.1%] and 54.9 mmHg [7.2%]) [160][165]. In contrast to most cancer cell lines, which preliminary depend on anaerobic glycolysis referred to as the Warburg effect [166]), the metabolism of some AML cells importantly depends on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [167][168][169]. Furthermore, leukemic cells can switch metabolism depending on environmental conditions such as oxidative stress, which may confer a selective advantage of leukemia cells over normal hematopoietic cells [170].

3.3. Developmental Changes in the Bone Marrow Microenvironment

Along with the above-mentioned ontogenic changes in hematopoietic development, there are noteworthy age-related differences in the fetal, neonatal, and adult hematopoietic and leukemic BMMs. The healthy fetal liver provides a unique environment that ensures enormous HSC-expansion without malignant transformation. The results of various studies focusing on the fetal liver niche suggest an important role of fetal liver stromal cells in supporting the massive expansion of early HSCs through the expression and secretion of pivotal hematopoietic mediators, including angiopoietin-like 2 and 3, TPO, and IGF-2 (reviewed in [171][172]). The combination of the attracting factors CXCL-12 and SCF synergistically increase migration of fetal liver HSCs to its niche [173].

In the postnatal period, it has been reported that HSCs possess increased CXCL-12 expression and high cell cycling activity, which are linked to an engraftment defect that can be reversed by antagonizing the CXCL-12/CXCR-4 interplay [174]. Intriguingly, in recent studies, investigating the neonatal and adult BMM, transplantation of HSCs into neonatal mice resulted in a higher regeneration capacity than in adult BMM. Conversely, the self-renewal of LSCs, when transplanted into adult BMM, was greater than that in neonatal models, which appears consistent with prognostic differences in adult and childhood AML [175]. In addition, primitive mesenchymal stromal cells (PDGF-R+ and SCA-1+) are more abundant in the neonatal environment and secrete higher levels of pivotal microenvironmental mediators, such as Jag-1 and CXCL-12. This raises the question of whether these age-dependent microenvironmental changes could be causative for the observed changes in hematopoietic and leukemic cell engraftment, which has been confirmed by further switching transplantation experiments [175]. However, considering age as a prognostic factor, particularly in pediatric and young adult AML [176][177], the clinical prognostic impact of age-dependent changes in the leukemic BMM in children versus adults is still unknown.

References

- Rasche, M.; Zimmermann, M.; Borschel, L.; Bourquin, J.; Dworzak, M.; Klingebiel, T.; Lehrnbecher, T.; Creutzig, U.; Klusmann, J.; Reinhardt, D. Successes and challenges in the treatment of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: A retrospective analysis of the AML-BFM trials from 1987 to 2012. Leukemia 2018, 32, 2167–2177.

- Kaspers, G.J.L.; Zimmermann, M.; Reinhardt, D.; Gibson, B.E.S.; Tamminga, R.Y.J.; Aleinikova, O.; Armendariz, H.; Dworzak, M.; Ha, S.-Y.; Hasle, H.; et al. Improved outcome in pediatric relapsed acute myeloid leukemia: Results of a randomized trial on liposomal daunorubicin by the International BFM Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 599–607.

- Fliedner, T.M.; Graessle, D.; Paulsen, C.; Reimers, K. Structure and function of bone marrow hemopoiesis: Mechanisms of response to ionizing radiation exposure. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2002, 17, 405–426.

- Baron, M.H.; Isern, J.; Fraser, S.T. The embryonic origins of erythropoiesis in mammals. Blood 2012, 119, 4828–4837.

- Ema, H.; Nakauchi, H. Expansion of hematopoietic stem cells in the developing liver of a mouse embryo. Blood 2000, 95, 2284–2288.

- Rebel, V.I.; Miller, C.L.; Eaves, C.J.; Lansdorp, P.M. The repopulation potential of fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells in mice exceeds that of their liver adult bone marrow counterparts. Blood 1996, 87, 3500–3507.

- Lapidot, T.; Sirard, C.; Vormoor, J.; Murdoch, B.; Hoang, T.; Caceres-Cortes, J.; Minden, M.; Paterson, B.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Dick, J.E. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature 1994, 367, 645–648.

- Guan, Y.; Gerhard, B.; Hogge, D.E. Detection, isolation, and stimulation of quiescent primitive leukemic progenitor cells from patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Blood 2003, 101, 3142–3149.

- Taussig, D.C.; Miraki-Moud, F.; Anjos-Afonso, F.; Pearce, D.J.; Allen, K.; Ridler, C.; Lillington, D.; Oakervee, H.; Cavenagh, J.; Agrawal, S.G.; et al. Anti-CD38 antibody-mediated clearance of human repopulating cells masks the heterogeneity of leukemia-initiating cells. Blood 2008, 112, 568–575.

- Goardon, N.; Marchi, E.; Atzberger, A.; Quek, L.; Schuh, A.; Soneji, S.; Woll, P.; Mead, A.; Alford, K.A.; Rout, R.; et al. Coexistence of LMPP-like and GMP-like leukemia stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 2011, 19, 138–152.

- Paguirigan, A.L.; Smith, J.; Meshinchi, S.; Carroll, M.; Maley, C.; Radich, J.P. Single-cell genotyping demonstrates complex clonal diversity in acute myeloid leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 281re2.

- Romer-Seibert, J.S.; Meyer, S.E. Genetic heterogeneity and clonal evolution in acute myeloid leukemia. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2020, 28, 64–70.

- Morita, K.; Wang, F.; Jahn, K.; Kuipers, J.; Yan, Y.; Matthews, J.; Little, L.; Gumbs, C.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; et al. Clonal Evolution of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Revealed by High-Throughput Single-Cell Genomics. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–17.

- Colmone, A.; Amorim, M.; Pontier, A.L.; Wang, S.; Jablonski, E.; Sipkins, D.A. Leukemic cells create bone marrow niches that disrupt the behavior of normal hematopoietic progenitor cells. Science 2008, 322, 1861–1865.

- Zhou, H.-S.; Carter, B.Z.; Andreeff, M. Bone marrow niche-mediated survival of leukemia stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia: Yin and Yang. Cancer Biol. Med. 2016, 13, 248–259.

- Lane, S.W.; Scadden, D.T.; Gilliland, D.G. The leukemic stem cell niche: Current concepts and therapeutic opportunities. Blood 2009, 114, 1150–1157.

- Ayala, F.; Dewar, R.; Kieran, M.; Kalluri, R. Contribution of bone microenvironment to leukemogenesis and leukemia progression. Leukemia 2009, 23, 2233–2241.

- Kokkaliaris, K.D.; Scadden, D.T. Cell interactions in the bone marrow microenvironment affecting myeloid malignancies. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 3795–3803.

- Meyer, L.K.; Hermiston, M.L. The bone marrow microenvironment as a mediator of chemoresistance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. CDR 2019, 2, 1164–1177.

- Blau, O.; Hofmann, W.-K.; Baldus, C.D.; Thiel, G.; Serbent, V.; Schümann, E.; Thiel, E.; Blau, I.W. Chromosomal aberrations in bone marrow mesenchymal stroma cells from patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloblastic leukemia. Exp. Hematol. 2007, 35, 221–229.

- Kumar, B.; Garcia, M.; Weng, L.; Jung, X.; Murakami, J.L.; Hu, X.; McDonald, T.; Lin, A.; Kumar, A.R.; DiGiusto, D.L.; et al. Acute myeloid leukemia transforms the bone marrow niche into a leukemia-permissive microenvironment through exosome secretion. Leukemia 2018, 32, 575–587.

- Geyh, S.; Rodríguez-Paredes, M.; Jäger, P.; Khandanpour, C.; Cadeddu, R.-P.; Gutekunst, J.; Wilk, C.M.; Fenk, R.; Zilkens, C.; Hermsen, D.; et al. Functional inhibition of mesenchymal stromal cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2016, 30, 683–691.

- Schepers, K.; Pietras, E.M.; Reynaud, D.; Flach, J.; Binnewies, M.; Garg, T.; Wagers, A.J.; Hsiao, E.C.; Passegué, E. Myeloproliferative neoplasia remodels the endosteal bone marrow niche into a self-reinforcing leukemic niche. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 13, 285–299.

- Tavassoli, M. Handbook of the Hemopoietic Microenvironment; Humana Press: Clifton, NJ, USA, 1989.

- Schofield, R. The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood Cells 1978, 4, 7–25.

- Lo Celso, C.; Fleming, H.E.; Wu, J.W.; Zhao, C.X.; Miake-Lye, S.; Fujisaki, J.; Côté, D.; Rowe, D.W.; Lin, C.P.; Scadden, D.T. Live-animal tracking of individual haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in their niche. Nature 2009, 457, 92–96.

- Gong, J.K. Endosteal marrow: A rich source of hematopoietic stem cells. Science 1978, 199, 1443–1445.

- Lord, B.I. The architecture of bone marrow cell populations. Int. J. Cell Cloning 1990, 8, 317–331.

- Cheng, T.; Rodrigues, N.; Shen, H.; Yang, Y.; Dombkowski, D.; Sykes, M.; Scadden, D.T. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence maintained by p21cip1/waf1. Science 2000, 287, 1804–1808.

- Taichman, R.S.; Reilly, M.J.; Emerson, S.G. Human osteoblasts support human hematopoietic progenitor cells in vitro bone marrow cultures. Blood 1996, 87, 518–524.

- Zhang, J.; Niu, C.; Ye, L.; Huang, H.; He, X.; Tong, W.G.; Ross, J.; Haug, J.; Johnson, T.; Feng, J.Q.; et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature 2003, 425, 577–584.

- Visnjic, D.; Kalajzic, Z.; Rowe, D.W.; Katavic, V.; Lorenzo, J.; Aguila, H.L. Hematopoiesis is severely altered in mice with an induced osteoblast deficiency. Blood 2004, 103, 3258–3264.

- Calvi, L.M.; Adams, G.B.; Weibrecht, K.W.; Weber, J.M.; Olson, D.P.; Knight, M.C.; Martin, R.P.; Schipani, E.; Divieti, P.; Bringhurst, F.R.; et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature 2003, 425, 841–846.

- Hosokawa, K.; Arai, F.; Yoshihara, H.; Iwasaki, H.; Hembree, M.; Yin, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Gomei, Y.; Takubo, K.; Shiama, H.; et al. Cadherin-based adhesion is a potential target for niche manipulation to protect hematopoietic stem cells in adult bone marrow. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 6, 194–198.

- Arai, F.; Hosokawa, K.; Toyama, H.; Matsumoto, Y.; Suda, T. Role of N-cadherin in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow niche. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1266, 72–77.

- Kiel, M.J.; Acar, M.; Radice, G.L.; Morrison, S.J. Hematopoietic stem cells do not depend on N-cadherin to regulate their maintenance. Cell Stem Cell 2009, 4, 170–179.

- Bromberg, O.; Frisch, B.J.; Weber, J.M.; Porter, R.L.; Civitelli, R.; Calvi, L.M. Osteoblastic N-cadherin is not required for microenvironmental support and regulation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood 2012, 120, 303–313.

- Qian, H.; Buza-Vidas, N.; Hyland, C.D.; Jensen, C.T.; Antonchuk, J.; Månsson, R.; Thoren, L.A.; Ekblom, M.; Alexander, W.S.; Jacobsen, S.E. Critical role of thrombopoietin in maintaining adult quiescent hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2007, 1, 671–684.

- Yoshihara, H.; Arai, F.; Hosokawa, K.; Hagiwara, T.; Takubo, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Gomei, Y.; Iwasaki, H.; Matsuoka, S.; Miyamoto, K.; et al. Thrombopoietin/MPL signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and interaction with the osteoblastic niche. Cell Stem Cell 2007, 1, 685–697.

- Audet, J.; Miller, C.L.; Eaves, C.J.; Piret, J.M. Common and distinct features of cytokine effects on hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells revealed by dose-response surface analysis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2002, 80, 393–404.

- Driessen, R.L.; Johnston, H.M.; Nilsson, S.K. Membrane-bound stem cell factor is a key regulator in the initial lodgment of stem cells within the endosteal marrow region. Exp. Hematol. 2003, 31, 1284–1291.

- Ara, T.; Tokoyoda, K.; Sugiyama, T.; Egawa, T.; Kawabata, K.; Nagasawa, T. Long-Term Hematopoietic Stem Cells Require Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1 for Colonizing Bone Marrow during Ontogeny. Immunity 2003, 19, 257–267.

- Sugiyama, T.; Kohara, H.; Noda, M.; Nagasawa, T. Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity 2006, 25, 977–988.

- Jung, Y.; Wang, J.; Schneider, A.; Sun, Y.-X.; Koh-Paige, A.J.; Osman, N.I.; McCauley, L.K.; Taichman, R.S. Regulation of SDF-1 (CXCL12) production by osteoblasts; a possible mechanism for stem cell homing. Bone 2006, 38, 497–508.

- Ding, L.; Saunders, T.L.; Enikolopov, G.; Morrison, S.J. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 2012, 481, 457–462.

- Greenbaum, A.; Hsu, Y.-M.S.; Day, R.B.; Schuettpelz, L.G.; Christopher, M.J.; Borgerding, J.N.; Nagasawa, T.; Link, D.C. CXCL12 in early mesenchymal progenitors is required for haematopoietic stem-cell maintenance. Nature 2013, 495, 227–230.

- El-Amin, S.F.; Lu, H.H.; Khan, Y.; Burems, J.; Mitchell, J.; Tuan, R.S.; Laurencin, C.T. Extracellular matrix production by human osteoblasts cultured on biodegradable polymers applicable for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 1213–1221.

- Stier, S.; Ko, Y.; Forkert, R.; Lutz, C.; Neuhaus, T.; Grünewald, E.; Cheng, T.; Dombkowski, D.; Calvi, L.M.; Rittling, S.R.; et al. Osteopontin is a hematopoietic stem cell niche component that negatively regulates stem cell pool size. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 201, 1781–1791.

- Grassinger, J.; Haylock, D.N.; Storan, M.J.; Haines, G.O.; Williams, B.; Whitty, G.A.; Vinson, A.R.; Be, C.L.; Li, S.; Sørensen, E.S.; et al. Thrombin-cleaved osteopontin regulates hemopoietic stem and progenitor cell functions through interactions with alpha9beta1 and alpha4beta1 integrins. Blood 2009, 114, 49–59.

- Cao, H.; Cao, B.; Heazlewood, C.K.; Domingues, M.; Sun, X.; Debele, E.; McGregor, N.E.; Sims, N.A.; Heazlewood, S.Y.; Nilsson, S.K. Osteopontin is An Important Regulative Component of the Fetal Bone Marrow Hematopoietic Stem Cell Niche. Cells 2019, 8, 985.

- Kollet, O.; Dar, A.; Shivtiel, S.; Kalinkovich, A.; Lapid, K.; Sztainberg, Y.; Tesio, M.; Samstein, R.M.; Goichberg, P.; Spiegel, A.; et al. Osteoclasts degrade endosteal components and promote mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 657–664.

- Adams, G.B.; Chabner, K.T.; Alley, I.R.; Olson, D.P.; Szczepiorkowski, Z.M.; Poznansky, M.C.; Kos, C.H.; Pollak, M.R.; Brown, E.M.; Scadden, D.T. Stem cell engraftment at the endosteal niche is specified by the calcium-sensing receptor. Nature 2006, 439, 599–603.

- Xie, Y.; Yin, T.; Wiegraebe, W.; He, X.C.; Miller, D.; Stark, D.; Perko, K.; Alexander, R.; Schwartz, J.; Grindley, J.C.; et al. Detection of functional haematopoietic stem cell niche using real-time imaging. Nature 2009, 457, 97–101.

- Christodoulou, C.; Joel, A.S.; Shu-Chi, A.Y.; Turcotte, R.; Konstantinos, D.K.; Panero, R.; Ramos, A.; Guo, G.; Seyedhassantehrani, N.; Tatiana, V.E.; et al. Live-animal imaging of native haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Nature 2020, 578, 278–283.

- Kiel, M.J.; Radice, G.L.; Morrison, S.J. Lack of evidence that hematopoietic stem cells depend on N-cadherin-mediated adhesion to osteoblasts for their maintenance. Cell Stem Cell 2007, 1, 204–217.

- Miyamoto, K.; Yoshida, S.; Kawasumi, M.; Hashimoto, K.; Kimura, T.; Sato, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Miyauchi, Y.; Hoshi, H.; Iwasaki, R.; et al. Osteoclasts are dispensable for hematopoietic stem cell maintenance and mobilization. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 2175–2181.

- Mancini, S.J.C.; Mantei, N.; Dumortier, A.; Suter, U.; MacDonald, H.R.; Radtke, F. Jagged1-dependent Notch signaling is dispensable for hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Blood 2005, 105, 2340–2342.

- Ding, L.; Morrison, S.J. Haematopoietic stem cells and early lymphoid progenitors occupy distinct bone marrow niches. Nature 2013, 495, 231–235.

- Acar, M.; Kocherlakota, K.S.; Murphy, M.M.; Peyer, J.G.; Oguro, H.; Inra, C.N.; Jaiyeola, C.; Zhao, Z.; Luby-Phelps, K.; Morrison, S.J. Deep imaging of bone marrow shows non-dividing stem cells are mainly perisinusoidal. Nature 2015, 526, 126–130.

- Nombela-Arrieta, C.; Pivarnik, G.; Winkel, B.; Canty, K.J.; Harley, B.; Mahoney, J.E.; Park, S.-Y.; Lu, J.; Protopopov, A.; Silberstein, L.E. Quantitative imaging of haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell localization and hypoxic status in the bone marrow microenvironment. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 533–543.

- Kusumbe, A.P.; Ramasamy, S.K.; Adams, R.H. Coupling of angiogenesis and osteogenesis by a specific vessel subtype in bone. Nature 2014, 507, 323–328.

- Méndez-Ferrer, S.; Michurina, T.V.; Ferraro, F.; Mazloom, A.R.; Macarthur, B.D.; Lira, S.A.; Scadden, D.T.; Ma’ayan, A.; Enikolopov, G.N.; Frenette, P.S. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature 2010, 466, 829–834.

- Kiel, M.J.; Yilmaz, O.H.; Iwashita, T.; Yilmaz, O.H.; Terhorst, C.; Morrison, S.J. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell 2005, 121, 1109–1121.

- Baryawno, N.; Przybylski, D.; Monika, S.K.; Kfoury, Y.; Severe, N.; Gustafsson, K.; Konstantinos, D.K.; Mercier, F.; Tabaka, M.; Hofree, M.; et al. A Cellular Taxonomy of the Bone Marrow Stroma in Homeostasis and Leukemia. Cell 2019, 177, 1915–1932.e16.

- Kunisaki, Y.; Bruns, I.; Scheiermann, C.; Ahmed, J.; Pinho, S.; Zhang, D.; Mizoguchi, T.; Wei, Q.; Lucas, D.; Ito, K.; et al. Arteriolar niches maintain haematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Nature 2013, 502, 637–643.

- Itkin, T.; Gur-Cohen, S.; Spencer, J.A.; Schajnovitz, A.; Ramasamy, S.K.; Kusumbe, A.P.; Ledergor, G.; Jung, Y.; Milo, I.; Poulos, M.G.; et al. Distinct bone marrow blood vessels differentially regulate hematopoiesis. Nature 2016, 532, 323–328.

- Pinho, S.; Marchand, T.; Yang, E.; Wei, Q.; Nerlov, C.; Frenette, P.S. Lineage-Biased Hematopoietic Stem Cells Are Regulated by Distinct Niches. Dev. Cell 2018, 44, 634–641.

- Omatsu, Y.; Sugiyama, T.; Kohara, H.; Kondoh, G.; Fujii, N.; Kohno, K.; Nagasawa, T. The essential functions of adipo-osteogenic progenitors as the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell niche. Immunity 2010, 33, 387–399.

- Xu, C.; Gao, X.; Wei, Q.; Nakahara, F.; Zimmerman, S.E.; Mar, J.; Frenette, P.S. Stem cell factor is selectively secreted by arterial endothelial cells in bone marrow. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2449.

- Hooper, A.T.; Butler, J.M.; Nolan, D.J.; Kranz, A.; Iida, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Kopp, H.-G.; Shido, K.; Petit, I.; Yanger, K.; et al. Engraftment and reconstitution of hematopoiesis is dependent on VEGFR2-mediated regeneration of sinusoidal endothelial cells. Cell Stem Cell 2009, 4, 263–274.

- Butler, J.M.; Nolan, D.J.; Vertes, E.L.; Varnum-Finney, B.; Kobayashi, H.; Hooper, A.T.; Seandel, M.; Shido, K.; White, I.A.; Kobayashi, M.; et al. Endothelial cells are essential for the self-renewal and repopulation of Notch-dependent hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 6, 251–264.

- Gerber, H.-P.; Malik, A.K.; Solar, G.P.; Sherman, D.; Liang, X.H.; Meng, G.; Hong, K.; Marsters, J.C.; Ferrara, N. VEGF regulates haematopoietic stem cell survival by an internal autocrine loop mechanism. Nature 2002, 417, 954–958.

- Fang, S.; Chen, S.; Nurmi, H.; Leppänen, V.-M.; Jeltsch, M.; Scadden, D.T.; Silberstein, L.; Mikkola, H.; Alitalo, K. VEGF-C Protects the Integrity of Bone Marrow Perivascular Niche. Blood 2020, 136, 1871–1883.

- Winkler, I.G.; Barbier, V.; Nowlan, B.; Jacobsen, R.N.; Forristal, C.E.; Patton, J.T.; Magnani, J.L.; Lévesque, J.-P. Vascular niche E-selectin regulates hematopoietic stem cell dormancy, self renewal and chemoresistance. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1651–1657.

- Sipkins, D.A.; Wei, X.; Wu, J.W.; Runnels, J.M.; Côté, D.; Means, T.K.; Luster, A.D.; Scadden, D.T.; Lin, C.P. In vivo imaging of specialized bone marrow endothelial microdomains for tumor engraftment. Nature 2005, 435, 969–973.

- Bruns, I.; Lucas, D.; Pinho, S.; Ahmed, J.; Lambert, M.P.; Kunisaki, Y.; Scheiermann, C.; Schiff, L.; Poncz, M.; Bergman, A.; et al. Megakaryocytes regulate hematopoietic stem cell quiescence through CXCL4 secretion. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 1315–1320.

- Nakamura-Ishizu, A.; Takubo, K.; Fujioka, M.; Suda, T. Megakaryocytes are essential for HSC quiescence through the production of thrombopoietin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 454, 353–357.

- Zhao, M.; Perry, J.M.; Marshall, H.; Venkatraman, A.; Qian, P.; He, X.C.; Ahamed, J.; Li, L. Megakaryocytes maintain homeostatic quiescence and promote post-injury regeneration of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 1321–1326.

- Scandura, J.M.; Boccuni, P.; Massagué, J.; Nimer, S.D. Transforming growth factor beta-induced cell cycle arrest of human hematopoietic cells requires p57KIP2 up-regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 15231–15236.

- Yamazaki, S.; Iwama, A.; Takayanagi, S.; Eto, K.; Ema, H.; Nakauchi, H. TGF-beta as a candidate bone marrow niche signal to induce hematopoietic stem cell hibernation. Blood 2009, 113, 1250–1256.

- Katayama, Y.; Battista, M.; Kao, W.-M.; Hidalgo, A.; Peired, A.J.; Thomas, S.A.; Frenette, P.S. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egress from bone marrow. Cell 2006, 124, 407–421.

- Yamazaki, S.; Ema, H.; Karlsson, G.; Yamaguchi, T.; Miyoshi, H.; Shioda, S.; Taketo, M.M.; Karlsson, S.; Iwama, A.; Nakauchi, H. Nonmyelinating Schwann cells maintain hematopoietic stem cell hibernation in the bone marrow niche. Cell 2011, 147, 1146–1158.

- Heidt, T.; Sager, H.B.; Courties, G.; Dutta, P.; Iwamoto, Y.; Zaltsman, A.; von zur Muhlen, C.; Bode, C.; Fricchione, G.L.; Denninger, J.; et al. Chronic variable stress activates hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 754–758.

- Spiegel, A.; Shivtiel, S.; Kalinkovich, A.; Ludin, A.; Netzer, N.; Goichberg, P.; Azaria, Y.; Resnick, I.; Hardan, I.; Ben-Hur, H.; et al. Catecholaminergic neurotransmitters regulate migration and repopulation of immature human CD34+ cells through Wnt signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8, 1123–1131.

- Méndez-Ferrer, S.; Lucas, D.; Battista, M.; Frenette, P.S. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature 2008, 452, 442–447.

- García-García, A.; Korn, C.; García-Fernández, M.; Domingues, O.; Villadiego, J.; Martín-Pérez, D.; Isern, J.; Bejarano-García, J.A.; Zimmer, J.; Pérez-Simón, J.A.; et al. Dual cholinergic signals regulate daily migration of hematopoietic stem cells and leukocytes. Blood 2019, 133, 224–236.

- Robles, H.; Park, S.; Joens, M.S.; Fitzpatrick, J.A.J.; Craft, C.S.; Scheller, E.L. Characterization of the bone marrow adipocyte niche with three-dimensional electron microscopy. Bone 2019, 118, 89–98.

- Naveiras, O.; Nardi, V.; Wenzel, P.L.; Hauschka, P.V.; Fahey, F.; Daley, G.Q. Bone-marrow adipocytes as negative regulators of the haematopoietic microenvironment. Nature 2009, 460, 259–263.

- Zhu, R.-J.; Wu, M.-Q.; Li, Z.-J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, K.-Y. Hematopoietic recovery following chemotherapy is improved by BADGE-induced inhibition of adipogenesis. Int. J. Hematol. 2013, 97, 58–72.

- Zhou, B.O.; Yu, H.; Yue, R.; Zhao, Z.; Rios, J.J.; Naveiras, O.; Morrison, S.J. Bone marrow adipocytes promote the regeneration of stem cells and haematopoiesis by secreting SCF. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 891–903.

- Claycombe, K.; King, L.E.; Fraker, P.J. A role for leptin in sustaining lymphopoiesis and myelopoiesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105.

- DiMascio, L.; Voermans, C.; Uqoezwa, M.; Duncan, A.; Lu, D.; Wu, J.; Sankar, U.; Reya, T. Identification of adiponectin as a novel hemopoietic stem cell growth factor. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 3511–3520.

- Wilson, A.; Fu, H.; Schiffrin, M.; Winkler, C.; Koufany, M.; Jouzeau, J.-Y.; Bonnet, N.; Gilardi, F.; Renevey, F.; Luther, S.A.; et al. Lack of Adipocytes Alters Hematopoiesis in Lipodystrophic Mice. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2573.

- Chow, A.; Lucas, D.; Hidalgo, A.; Méndez-Ferrer, S.; Hashimoto, D.; Scheiermann, C.; Battista, M.; Leboeuf, M.; Prophete, C.; van Rooijen, N.; et al. Bone marrow CD169+ macrophages promote the retention of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the mesenchymal stem cell niche. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 261–271.

- Zhao, M.; Tao, F.; Venkatraman, A.; Li, Z.; Smith, S.E.; Unruh, J.; Chen, S.; Ward, C.; Qian, P.; Perry, J.M.; et al. N-Cadherin-Expressing Bone and Marrow Stromal Progenitor Cells Maintain Reserve Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 652–669.e6.

- Hira, V.V.V.; Van, N.C.; Carraway, H.E.; Maciejewski, J.P.; Molenaar, R.J. Novel therapeutic strategies to target leukemic cells that hijack compartmentalized continuous hematopoietic stem cell niches. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2017, 1868, 183–198.

- Spencer, J.A.; Ferraro, F.; Roussakis, E.; Klein, A.; Wu, J.; Runnels, J.M.; Zaher, W.; Mortensen, L.J.; Alt, C.; Turcotte, R.; et al. Direct measurement of local oxygen concentration in the bone marrow of live animals. Nature 2014, 508, 269–273.

- Rieger, C.T.; Fiegel, M. Microenvironmental oxygen partial pressure in acute myeloid leukemia: Is there really a role for hypoxia? Exp. Hematol. 2016, 44, 578–582.

- Eliasson, P.; Jönsson, J.-I. The hematopoietic stem cell niche: Low in oxygen but a nice place to be. J. Cell. Physiol. 2010, 222, 17–22.

- Takubo, K.; Goda, N.; Yamada, W.; Iriuchishima, H.; Ikeda, E.; Kubota, Y.; Shima, H.; Johnson, R.S.; Hirao, A.; Suematsu, M.; et al. Regulation of the HIF-1alpha level is essential for hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 7, 391–402.

- Suessbier, U.; Nombela-Arrieta, C. Assessing Cellular Hypoxic Status in Situ Within the Bone Marrow Microenvironment. In Stem Cell Mobilization; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 123–134.

- Karigane, D.; Takubo, K. Metabolic regulation of hematopoietic and leukemic stem/progenitor cells under homeostatic and stress conditions. Int. J. Hematol. 2017, 106, 18–26.

- Takubo, K.; Nagamatsu, G.; Kobayashi, C.I.; Nakamura-Ishizu, A.; Kobayashi, H.; Ikeda, E.; Goda, N.; Rahimi, Y.; Johnson, R.S.; Soga, T.; et al. Regulation of glycolysis by Pdk functions as a metabolic checkpoint for cell cycle quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 12, 49–61.

- Morikawa, T.; Takubo, K. Hypoxia regulates the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2016, 468, 13–22.

- Parmar, K.; Mauch, P.; Vergilio, J.-A.; Sackstein, R.; Down, J.D. Distribution of hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow according to regional hypoxia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 5431–5436.

- Wang, L.D.; Wagers, A.J. Dynamic niches in the origination and differentiation of haematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 643–655.

- Sendker, S.; Reinhardt, D.; Niktoreh, N. Redirecting the Immune Microenvironment in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancers 2021, 13, 1423.

- Dührsen, U.; Hossfeld, D.K. Stromal abnormalities in neoplastic bone marrow diseases. Ann. Hematol. 1996, 73, 53–70.

- Blau, O.; Baldus, C.D.; Hofmann, W.-K.; Thiel, G.; Nolte, F.; Burmeister, T.; Türkmen, S.; Benlasfer, O.; Schümann, E.; Sindram, A.; et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells of myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia patients have distinct genetic abnormalities compared with leukemic blasts. Blood 2011, 118, 5583–5592.

- Kim, Y.; Jekarl, D.W.; Kim, J.; Kwon, A.; Choi, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y.-J.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, Y.; Oh, I.-H.; et al. Genetic and epigenetic alterations of bone marrow stromal cells in myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia patients. Stem Cell Res. 2015, 14, 177–184.

- Kode, A.; Mosialou, I.; Manavalan, S.J.; Rathinam, C.V.; Friedman, R.A.; Teruya-Feldstein, J.; Bhagat, G.; Berman, E.; Kousteni, S. FoxO1-dependent induction of acute myeloid leukemia by osteoblasts in mice. Leukemia 2016, 30, 1–13.

- Kode, A.; Manavalan, J.S.; Mosialou, I.; Bhagat, G.; Rathinam, C.V.; Luo, N.; Khiabanian, H.; Lee, A.; Murty, V.V.; Friedman, R.; et al. Leukaemogenesis induced by an activating β-catenin mutation in osteoblasts. Nature 2014, 506, 240–244.

- Desbourdes, L.; Javary, J.; Charbonnier, T.; Ishac, N.; Bourgeais, J.; Iltis, A.; Chomel, J.-C.; Turhan, A.; Guilloton, F.; Tarte, K.; et al. Alteration Analysis of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells from De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients at Diagnosis. Stem Cells Dev. 2017, 26, 709–722.

- Wiseman, D.H. Donor cell leukemia: A review. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 2011, 17, 771–789.

- Sala-Torra, O.; Hanna, C.; Loken, M.R.; Flowers, M.E.D.; Maris, M.; Ladne, P.A.; Mason, J.R.; Senitzer, D.; Rodriguez, R.; Forman, S.J.; et al. Evidence of donor-derived hematologic malignancies after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 2006, 12, 511–517.

- Katz, F.; Reeves, B.R.; Alexander, S.; Kearney, L.; Chessells, J. Leukaemia arising in donor cells following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for beta thalassaemia demonstrated by immunological, DNA and molecular cytogenetic analysis. Br. J. Haematol. 1993, 85, 326–331.

- Lawler, M.; Locasciulli, A.; Longoni, D.; Schiro, R.; McCann, S.R. Leukaemic transformation of donor cells in a patient receiving a second allogeneic bone marrow transplant for severe aplastic anaemia. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2002, 29, 453–456.

- Boyd, C.N.; Ramberg, R.C.; Thomas, E.D. The incidence of recurrence of leukemia in donor cells after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Leuk. Res. 1982, 6, 833–837.

- Ruiz-Argüelles, G.J.; Ruiz-Delgado, G.J.; Garces-Eisele, J.; Ruiz-Arguelles, A.; Perez-Romano, B.; Reyes-Nuñez, V. Donor cell leukemia after non-myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation: A single institution experience. Leuk. Lymphoma 2009, 47, 1952–1955.

- Medyouf, H.; Mossner, M.; Jann, J.-C.; Nolte, F.; Raffel, S.; Herrmann, C.; Lier, A.; Eisen, C.; Nowak, V.; Zens, B.; et al. Myelodysplastic cells in patients reprogram mesenchymal stromal cells to establish a transplantable stem cell niche disease unit. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 824–837.

- Kim, J.-A.; Shim, J.-S.; Lee, G.-Y.; Yim, H.W.; Kim, T.-M.; Kim, M.; Leem, S.-H.; Lee, J.-W.; Min, C.-K.; Oh, I.-H. Microenvironmental remodeling as a parameter and prognostic factor of heterogeneous leukemogenesis in acute myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 2222–2231.

- Chen, T.; Zhang, G.; Kong, L.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Dong, M. Leukemia-derived exosomes induced IL-8 production in bone marrow stromal cells to protect the leukemia cells against chemotherapy. Life Sci. 2019, 221, 187–195.

- Kumar, B.; Garcia, M.; Murakami, J.L.; Chen, C.-C. Exosome-mediated microenvironment dysregulation in leukemia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 464–470.

- Hong, C.S.; Muller, L.; Boyiadzis, M.; Whiteside, T.L. Isolation and characterization of CD34+ blast-derived exosomes in acute myeloid leukemia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103310.

- Korn, C.; Méndez-Ferrer, S. Myeloid malignancies and the microenvironment. Blood 2017, 129, 811–822.

- Jacamo, R.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, W.; Zhang, M.; Spaeth, E.L.; Wang, Y.; Battula, V.L.; Mak, P.Y.; Schallmoser, K.; et al. Reciprocal leukemia-stroma VCAM-1/VLA-4-dependent activation of NF-κB mediates chemoresistance. Blood 2014, 123, 2691–2702.

- Matsunaga, T.; Takemoto, N.; Sato, T.; Takimoto, R.; Tanaka, I.; Fujimi, A.; Akiyama, T.; Kuroda, H.; Kawano, Y.; Kobune, M.; et al. Interaction between leukemic-cell VLA-4 and stromal fibronectin is a decisive factor for minimal residual disease of acute myelogenous leukemia. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 1158–1165.

- Griffin, J.D.; Rambaldi, A.; Vellenga, E.; Young, D.C.; Ostapovicz, D.; Cannistra, S.A. Secretion of interleukin-1 by acute myeloblastic leukemia cells in vitro induces endothelial cells to secrete colony stimulating factors. Blood 1987, 70, 1218–1221.

- Long, X.; Man, C.; Narayanan, P.; Seashore, E.; Redell, M. Inhibition of BMP-Smad Pathway Reduces Leukemic Stemness in Pediatric AML. Blood 2019, 134, 3731.

- Krause, D.S.; Fulzele, K.; Catic, A.; Sun, C.C.; Dombkowski, D.; Hurley, M.P.; Lezeau, S.; Attar, E.; Wu, J.Y.; Lin, H.Y.; et al. Differential regulation of myeloid leukemias by the bone marrow microenvironment. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1513–1517.

- Tabe, Y.; Shi, Y.X.; Zeng, Z.; Jin, L.; Shikami, M.; Hatanaka, Y.; Miida, T.; Hsu, F.J.; Andreeff, M.; Konopleva, M. TGF-β-Neutralizing Antibody 1D11 Enhances Cytarabine-Induced Apoptosis in AML Cells in the Bone Marrow Microenvironment. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62785.

- Dong, M.; Blobe, G.C. Role of transforming growth factor-β in hematologic malignancies. Blood 2006, 107, 4589–4596.

- Wu, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Chen, Q.; Peng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, J.; Jin, J.; Xu, H. Increased frequencies of T helper type 17 cells in the peripheral blood of patients with acute myeloid leukaemia. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2009, 158, 199–204.

- Szczepanski, M.J.; Szajnik, M.; Welsh, A.; Whiteside, T.L.; Boyiadzis, M. Blast-derived microvesicles in sera from patients with acute myeloid leukemia suppress natural killer cell function via membrane-associated transforming growth factor-beta1. Haematologica 2011, 96, 1302–1309.

- Gong, Y.; Zhao, M.; Yang, W.; Gao, A.; Yin, X.; Hu, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Hao, S.; Cheng, T.; et al. Megakaryocyte-derived excessive transforming growth factor β1 inhibits proliferation of normal hematopoietic stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Exp. Hematol. 2018, 60, 40–46.e2.

- WU, H.A.O.; LI, P.; SHAO, N.A.; MA, J.; JI, M.I.N.; SUN, X.; MA, D.; JI, C. Aberrant expression of Treg-associated cytokine IL-35 along with IL-10 and TGF-β in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncol. Lett. 2012, 3, 1119–1123.

- Tabe, Y.; Jin, L.; Hatanaka, Y.; Miida, T.; Kornblau, S.M.; Andreeff, M.; Konopleva, M. TGF-β1 Supports Leukemia Cell Survival Via Negative Regulation of FLI-1 Transcription Factor, ERK Inactivation and MMP-1 Secretion. Blood 2012, 120, 3543.

- Vannucchi, A.M.; Bianchi, L.; Cellai, C.; Paoletti, F.; Rana, R.A.; Lorenzini, R.; Migliaccio, G.; Migliaccio, A.R. Development of myelofibrosis in mice genetically impaired for GATA-1 expression (GATA-1(low) mice). Blood 2002, 100, 1123–1132.

- Arai, F.; Hirao, A.; Ohmura, M.; Sato, H.; Matsuoka, S.; Takubo, K.; Ito, K.; Koh, G.Y.; Suda, T. Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell 2004, 118, 149–161.

- Rameshwar, P.; Chang, V.T.; Thacker, U.F.; Gascón, P. Systemic transforming growth factor-beta in patients with bone marrow fibrosis—pathophysiological implications. Am. J. Hematol. 1998, 59, 133–142.

- Hack, T.; Bertram, S.; Blair, H.; Borger, V.; Busche, G.; Denson, L.; Fruth, E.; Giebel, B.; Heidenreich, O.; Klein-Hitpass, L.; et al. Exposure of patient-derived mesenchymal stromal cells to TGFB1 supports fibrosis induction in a pediatric acute megakaryoblastic leukemia model. Mol. Cancer Res. 2020, 18, 1603–1612.

- Hong, C.-S.; Muller, L.; Whiteside, T.L.; Boyiadzis, M. Plasma exosomes as markers of therapeutic response in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 160.

- Zhou, J.; Wang, S.; Sun, K.; Chng, W.-J. The emerging roles of exosomes in leukemogeneis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 50698–50707.

- Doepfner, K.T.; Spertini, O.; Arcaro, A. Autocrine insulin-like growth factor-I signaling promotes growth and survival of human acute myeloid leukemia cells via the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Leukemia 2007, 21, 1921–1930.

- Estrov, Z.; Meir, R.; Barak, Y.; Zaizov, R.; Zadik, Z. Human growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 enhance the proliferation of human leukemic blasts. J. Clin. Oncol. 1991, 9, 394–399.

- Klusmann, J.-H.; Godinho, F.J.; Heitmann, K.; Maroz, A.; Koch, M.L.; Reinhardt, D.; Orkin, S.H.; Li, Z. Developmental stage-specific interplay of GATA1 and IGF signaling in fetal megakaryopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 1659–1672.

- Karmali, R.; Larson, M.L.; Shammo, J.M.; Basu, S.; Christopherson, K.; Borgia, J.A.; Venugopal, P. Impact of insulin-like growth factor 1 and insulin-like growth factor binding proteins on outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2015, 56, 3135–3142.

- Verhagen, H.J.M.P.; van Gils, N.; Martiañez, T.; van Rhenen, A.; Rutten, A.; Denkers, F.; de Leeuw, D.C.; Smit, M.A.; Tsui, M.-L.; de Vos Klootwijk, L.L.E.; et al. IGFBP7 Induces Differentiation and Loss of Survival of Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia Stem Cells without Affecting Normal Hematopoiesis. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 3021–3035.

- Hanoun, M.; Zhang, D.; Mizoguchi, T.; Pinho, S.; Pierce, H.; Kunisaki, Y.; Lacombe, J.; Armstrong, S.A.; Dührsen, U.; Frenette, P.S. Acute myelogenous leukemia-induced sympathetic neuropathy promotes malignancy in an altered hematopoietic stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 15, 365–375.

- Battula, V.L.; Le, P.M.; Sun, J.C.; Nguyen, K.; Yuan, B.; Zhou, X.; Sonnylal, S.; McQueen, T.; Ruvolo, V.; Michel, K.A.; et al. AML-induced osteogenic differentiation in mesenchymal stromal cells supports leukemia growth. JCI Insight 2017, 2.

- Padró, T.; Bieker, R.; Ruiz, S.; Steins, M.; Retzlaff, S.; Bürger, H.; Büchner, T.; Kessler, T.; Herrera, F.; Kienast, J.; et al. Overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its cellular receptor KDR (VEGFR-2) in the bone marrow of patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2002, 16, 1302–1310.

- Aguayo, A.; Estey, E.; Kantarjian, H.; Mansouri, T.; Gidel, C.; Keating, M.; Giles, F.; Estrov, Z.; Barlogie, B.; Albitar, M. Cellular vascular endothelial growth factor is a predictor of outcome in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 1999, 94, 3717–3721.

- Dias, S.; Choy, M.; Alitalo, K.; Rafii, S. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-C signaling through FLT-4 (VEGFR-3) mediates leukemic cell proliferation, survival, and resistance to chemotherapy. Blood 2002, 99, 2179–2184.

- de Jonge, H.J.M.; Weidenaar, A.C.; Ter Elst, A.; Boezen, H.M.; Scherpen, F.J.G.; Bouma-Ter Steege, J.C.A.; Kaspers, G.J.L.; Goemans, B.F.; Creutzig, U.; Zimmermann, M.; et al. Endogenous vascular endothelial growth factor-C expression is associated with decreased drug responsiveness in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 924–930.

- Minchenko, A.; Bauer, T.; Salceda, S.; Caro, J. Hypoxic stimulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in vitro and in vivo. Lab. Investig. 1994, 71, 374–379.

- Jabari, M.; Farsani, M.A.; Salari, S.; Hamidpour, M.; Amiri, V.; Mohammadi, M.H. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-Α (HIF1α) and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A (VEGF-A) Expression in De Novo AML Patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 705–710.

- Coltella, N.; Percio, S.; Valsecchi, R.; Cuttano, R.; Guarnerio, J.; Ponzoni, M.; Pandolfi, P.P.; Melillo, G.; Pattini, L.; Bernardi, R. HIF factors cooperate with PML-RARα to promote acute promyelocytic leukemia progression and relapse. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014, 6, 640–650.

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Malek, S.N.; Zheng, P.; Liu, Y. Targeting HIF1α eliminates cancer stem cells in hematological malignancies. Cell Stem Cell 2011, 8, 399–411.

- Griessinger, E.; Anjos-Afonso, F.; Pizzitola, I.; Rouault-Pierre, K.; Vargaftig, J.; Taussig, D.; Gribben, J.; Lassailly, F.; Bonnet, D. A niche-like culture system allowing the maintenance of primary human acute myeloid leukemia-initiating cells: A new tool to decipher their chemoresistance and self-renewal mechanisms. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2014, 3, 520–529.

- Fiegl, M.; Samudio, I.; Clise-Dwyer, K.; Burks, J.K.; Mnjoyan, Z.; Andreeff, M. CXCR4 expression and biologic activity in acute myeloid leukemia are dependent on oxygen partial pressure. Blood 2009, 113, 1504–1512.

- Drolle, H.; Wagner, M.; Vasold, J.; Kütt, A.; Deniffel, C.; Sotlar, K.; Sironi, S.; Herold, T.; Rieger, C.; Fiegl, M. Hypoxia regulates proliferation of acute myeloid leukemia and sensitivity against chemotherapy. Leuk. Res. 2015, 39, 779–785.

- Abdul-Aziz, A.M.; Shafat, M.S.; Mehta, T.K.; Di Palma, F.; Lawes, M.J.; Rushworth, S.A.; Bowles, K.M. MIF-Induced Stromal PKCβ/IL8 Is Essential in Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 303–311.

- Abdul-Aziz, A.M.; Shafat, M.S.; Zaitseva, L.; Lawes, M.J.; Rushworth, S.A.; Bowles, K.M. Hypoxia Drives AML Proliferation in the Bone Marrow Microenvironment Via Macrophage Inhibitory Factor. Blood 2016, 128, 1721.

- Velasco-Hernandez, T.; Hyrenius-Wittsten, A.; Rehn, M.; Bryder, D.; Cammenga, J. HIF-1α can act as a tumor suppressor gene in murine acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2014, 124, 3597–3607.

- Harrison, J.S.; Rameshwar, P.; Chang, V.; Bandari, P. Oxygen saturation in the bone marrow of healthy volunteers. Blood 2002, 99, 394.

- WARBURG, O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science 1956, 123, 309–314.

- Miwa, H.; Shikami, M.; Goto, M.; Mizuno, S.; Takahashi, M.; Tsunekawa-Imai, N.; Ishikawa, T.; Mizutani, M.; Horio, T.; Gotou, M.; et al. Leukemia cells demonstrate a different metabolic perturbation provoked by 2-deoxyglucose. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 29, 2053–2057.

- Basak, N.P.; Banerjee, S. Mitochondrial dependency in progression of acute myeloid leukemia. Mitochondrion 2015, 21, 41–48.

- Molina, J.R.; Sun, Y.; Protopopova, M.; Gera, S.; Bandi, M.; Bristow, C.; McAfoos, T.; Morlacchi, P.; Ackroyd, J.; Agip, A.-N.A.; et al. An inhibitor of oxidative phosphorylation exploits cancer vulnerability. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1036–1046.

- Goto, M.; Miwa, H.; Suganuma, K.; Tsunekawa-Imai, N.; Shikami, M.; Mizutani, M.; Mizuno, S.; Hanamura, I.; Nitta, M. Adaptation of leukemia cells to hypoxic condition through switching the energy metabolism or avoiding the oxidative stress. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 76.

- Mahony, C.B.; Bertrand, J.Y. How HSCs Colonize and Expand in the Fetal Niche of the Vertebrate Embryo: An Evolutionary Perspective. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 34.

- Lewis, K.; Yoshimoto, M.; Takebe, T. Fetal liver hematopoiesis: From development to delivery. Stem Cell Res. 2021, 12, 139.

- Christensen, J.L.; Wright, D.E.; Wagers, A.J.; Weissman, I.L. Circulation and chemotaxis of fetal hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS Biol. 2004, 2, E75.

- Williams, D.A.; Xu, H.; Cancelas, J.A. Children are not little adults: Just ask their hematopoietic stem cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 2593–2596.

- Lee, G.-Y.; Jeong, S.-Y.; Lee, H.-R.; Oh, I.-H. Age-related differences in the bone marrow stem cell niche generate specialized microenvironments for the distinct regulation of normal hematopoietic and leukemia stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1007.

- Creutzig, U.; Büchner, T.; Sauerland, M.C.; Zimmermann, M.; Reinhardt, D.; Döhner, H.; Schlenk, R.F. Significance of age in acute myeloid leukemia patients younger than 30 years: A common analysis of the pediatric trials AML-BFM 93/98 and the adult trials AMLCG 92/99 and AMLSG HD93/98A. Cancer 2008, 112, 562–571.