| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alexander Zaika | + 3000 word(s) | 3000 | 2021-04-20 10:08:24 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 3000 | 2021-05-11 03:27:56 | | |

Video Upload Options

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the deadliest malignancies worldwide. In contrast to many other tumor types, gastric carcinogenesis is tightly linked to infectious events. Infections with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacterium and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) are the two most investigated risk factors for GC. These pathogens infect more than half of the world’s population. Fortunately, only a small fraction of infected individuals develops GC, suggesting high complexity of tumorigenic processes in the human stomach. Recent studies suggest that the multifaceted interplay between microbial, environmental, and host genetic factors underlies gastric tumorigenesis. Many aspects of these interactions still remain unclear.

1. Introduction

Approximately 13–15% of human cancers worldwide can be attributed to infectious agents [1]. One demonstrative example is gastric cancer (GC), which is strongly associated with infections caused by Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacteria and other pathogens. Despite all efforts, gastric cancer remains a serious clinical problem. Over seven hundred thousands of deaths related to GC have been reported in 2020, ranking the fourth most-deadliest tumor in the World [2]. The incidence of GC is characterized by complex dynamics and geographical variation. Its occurrence slowly declines in North America and most Western European countries, but its burden remains very high in Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe [3]. Multiple histological and anatomical classifications of GC have been proposed over time. For more than half a century, the characterization of GC was largely based on Lauren’s criteria, in which GC was divided into intestinal, diffuse and, undetermined types [4][5]. In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) expanded this classification by identifying papillary, tubular, mucinous and poorly cohesive (including signet ring cell carcinoma and other variants), and unusual histological variants [6].

Another approach to GC classification is based on the molecular profiling using gene expression and DNA sequencing analyses. A comprehensive study by the Cancer Genome Atlas consortium (TCGA) proposed four molecular subtypes of GC: (1) tumors positive for Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), (2) microsatellite unstable tumors (MSI), (3) genomically stable tumors (GS), and (4) tumors with chromosomal instability (CIN) [7]. More clinically relevant molecular classification has been presented by the Asian Cancer Research Group (ACRG). This study used gene expression data to describe molecular subtypes linked to distinct patterns of molecular alterations and disease progression and prognosis. Based on these criteria, GC was separated into four groups: MSI-high, microsatellite-stable/p53 inactive (MSS/TP53−), microsatellite-stable/p53 active (MSS/TP53+), and microsatellite-stable/epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (MSS/EMT) subtypes [8]. Additional classifications have also been proposed [9].

2. H. pylori and Gastric Cancer

H. pylori is a spiral-shaped gram-negative microaerophilic bacterium that, in the process of evolution, adapted to survive and thrive in the human stomach. Since the seminal discovery of H. pylori and its role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease by Robin Warren and Barry Marshall [10], studies of this pathogen have been continuing for more than three decades. Among many important findings during this period of time, discovery of the relationship between H. pylori and noncardia gastric cancer, and the characterization of gastric tumorigenesis as a stepwise inflammatory process, initiated by H. pylori, played key roles [11]. The stepwise model that emphasizes the role of chronic inflammation and consecutive pathological changes has been proposed by Dr. Pelayo Correa, and has stood the test of time [12]. According to this model, intestinal-type GC is the end result of lengthy progressive changes in the gastric mucosa that start with chronic gastritis, followed by atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia (IM), dysplasia and invasive tumor. In 1994, H. pylori was recognized as a type I carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [13]. The clinicopathological role of H. pylori was further highlighted by studies showing that H. pylori eradication reduces gastric inflammation and decreases the risk of premalignant and malignant lesions in the stomach [14]. Several effective anti–H. pylori treatment regiments have been developed and successfully used in clinic [15][16][17].

Besides IM, another type of metaplasia, called spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM), is also associated with chronic H. pylori infection and gastric adenocarcinoma [18]. It develops as a results of transdifferentiation of chief cells following persistent stomach injury and loss of parietal cells in the gastric oxyntic mucosa [18][19].

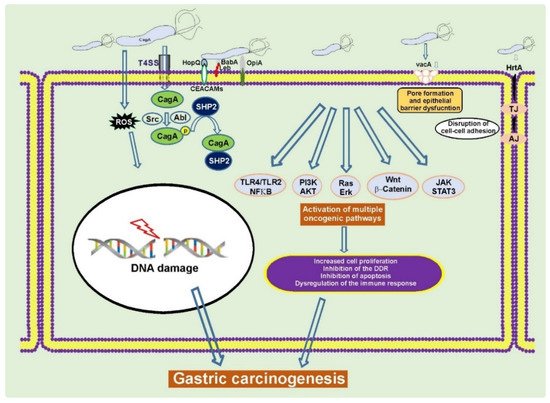

H. pylori typically infects humans at an early age, leading to decades-long chronic infection and mucosal injury that may progress to GC at older age. H. pylori is responsible for almost 90% of all noncardia gastric cancers [11][20]. Although infection with H. pylori is very common worldwide, only a small fraction of infected individuals develops GC, indicating complexity of tumorigenic interactions between bacteria and host cells. Among H. pylori virulence factors cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) protein and vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA) are the most studied determinants associated with gastric carcinogenesis (Figure 1) [21][22][23][24].

Figure 1. H. pylori alters cellular homeostasis during infection. H. pylori colonization of the human stomach is responsible for aberrant activation of multiple oncogenic pathways, induction of DNA damage, disruption of the epithelial barrier, and modulation of the host immune response. CagA, VacA, and other virulence factors play a key role in these processes [22][25][26].

2.1. The cag Pathogenicity Island (cag PAI) and CagA Protein

The cagA gene, which encodes CagA protein, is located at the 3′ end of the cag pathogenicity island, a 40-kilobase bacterial genomic DNA fragment that is thought to be acquired by horizontal transfer of genetic material. The products of the cag PAI form highly organized type IV secretion system (T4SS) pili that functions as a sophisticated molecular machine delivering CagA inside gastric epithelial cells. There are also evidences that bacterial lipopolysaccharides, peptidoglycans, and DNA can be delivered by the T4SS [22][26][27][28][29]. After translocation, CagA is phosphorylated by host tyrosine kinases belonging to the SRC and ABL families at the EPIYA (Glu-Pro-Ile-Tyr-Ala) repeatable motifs located at the carboxy-terminal end of the CagA molecule. The EPIYA motifs are responsible for binding of CagA to multiple host proteins and dysregulation of their functions. Currently, four distinct EPIYA types (-A, -B, -C, and -D) have been identified based on surrounding amino acid sequences. The EPIYA motifs are commonly assembled in the A-B-C(D) arrangements, where the EPIYA-C and rarely EPIYA-D fragments can be present in multiple copies. H. pylori strains carrying the EPIYA-C and EPIYA-D motifs have different geographical distribution. The EPIYA-C motif is typically found outside East Asia, whereas the East Asian strains predominantly carry the EPIYA-D motif [30].

This phenomenon has clinicopathological significance. Systematic review and meta-analysis of published research have shown that the presence of EPIYA-D and multiple EPIYA-C motifs are significantly associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer in the United States/Europe and Asia [31][32].

In addition to the EPIYA motif, the C-terminus of the CagA protein contains another repeatable sequence named the CagA-multimerization motif (CM) [33]. The CM motif comprises 16 amino acid residues and is responsible for homodimerization of CagA and interaction with PAR1b/MARK kinase, playing a critical role in the epithelial cell polarity. [33]. East Asian CagA usually has a single copy of East Asian type of the CM motif, while Western CagA retains multiple copies of Western type of the CM motifs. The polymorphism of the CM and EPIYA motifs explains differences in molecular weight of CagA protein that can vary from 120 to 145 kDa between H. pylori variants [33].

Based on current understanding, CagA is the most significant single factor defining gastric tumorigenesis. Multiple human studies have found considerable associations between infections with CagA-positive H. pylori bacteria and an increased risk of gastric cancer [21][34][35][36]. There are also multiple experimental evidences showing that CagA functions as an oncoprotein. CagA transgenic mice, in which effects of other virulence factors were excluded, developed gastric epithelial hyperplasia and hematopoietic and gastrointestinal malignancies, including gastric adenocarcinoma [37]. Similarly, transgenic expression of CagA in zebrafish causes intestinal epithelial hyperplasia and, in combination with loss of p53, produces intestinal small cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas [38]. CagA also enhances growth and invasion of tumors generated by expression of oncogenic Ras in Drosophila [39].

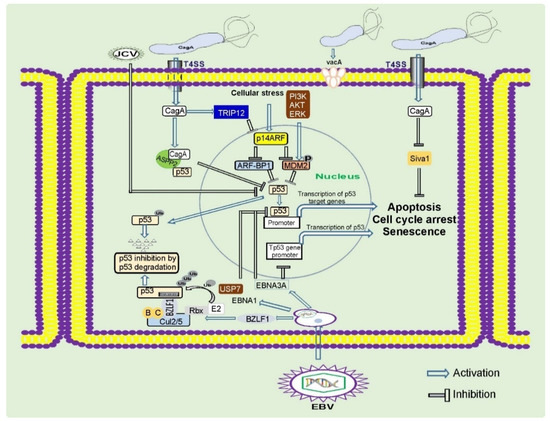

Oncogenic pursuit of CagA is mediated by aberrant activation of multiple signaling cascades that are known to be altered in gastric cancer (RAS/ERK, WNT/β-catenin, JAK/STAT, PI3K/AKT, and others) and inhibition of tumor suppressors. CagA is the first bacterial protein that has been shown to induce degradation of p53 tumor suppressor, activating the PI3K/AKT/MDM2/ARF-BP1 and ERK/MDM2-pathways [40][41] (Figure 2). Previously, only viral proteins, such as HPV E6, were known to degrade p53 [30]. CagA is responsible for altering expression of N-terminally truncated p53 isoforms: ∆133p53 and ∆160p53 [42]. Interestingly, the dysregulation of p53 occurs in a strain-specific manner, with tumorigenic H. pylori strains having a stronger ability to affect p53 [40][43]. Tumorigenic H. pylori strains also decrease activity of other tumor suppressors: p14ARF, SIVA1, and p27(KIP1) [43][44][45][46].

Figure 2. Regulation of tumor suppressor proteins by gastric pathogens. Gastric pathogens: H. pylori and oncogenic viruses inhibit key tumor suppressors proteins p53, p14ARF, and others. These events result in inhibition of the DNA damage and oncogenic stress responses, two key mechanisms important for prevention of gastric carcinogenesis.

Interaction of H. pylori with gastric cells increases the levels of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and induces oxidative stress and DNA damage in a CagA-dependent and -independent manner [47][48][49][50]. Although the entire spectrum of H. pylori–induced DNA damage is currently unknown, the formation of oxidized nitrated DNA lesions and single- and double-strand DNA breaks has been shown. Double-strand breaks in DNA are particularly detrimental, as these lesions are extremely difficult to repair resulting in highly cytotoxic and mutagenic effects [47][49][51][52][53][54][55][56]. H. pylori can also induce damage of mitochondrial DNA likely contributing to cellular senescence and gastric cancer initiation [57].

Induction of DNA damage by H. pylori is exacerbated by inhibition of p53 and multiple DNA repair pathways that are important for proper activation of the DNA damage response [40][42][49][52][58][59][60][61].

CagA is known to function as an anti-apoptotic protein. Multiple prosurvival factors and pathways have been shown to be induced by CagA, and among them are kinases AKT and ERK; antiapoptotic members of the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) protein family MCL-1, BCL-2, and BCL-Xl; and others [62][63][64][65]. CagA is responsible for the suppression of proapoptotic factors such as SIVA1, BIM, and BAD; downregulation of autophagy; and induction of inflammation [46][62]. Human infections with CagA-positive H. pylori strains are characterized by strong inflammation and severe damage of gastric tissues [66][67][68][69][70].

It has been reported that CagA protein has a profound impact on various cellular functions, including epithelial cell barrier, cell polarity, proliferation, apoptosis, EMT, autophagy, miRNA biogenesis, inflammatory and DNA damage responses, and others. It affects activities of multiple kinases and cell signaling pathways. A partial list includes the following: EGFR, c-MET, SRC, cABL, CSC, aPKC, PAR1, PI3K, AKT, FAK, GSK-3, JAK, PAK, MAP, MDM2, p53, p14ARF, p27, RAS, β-catenin, NFκB, and multiple NFκB-related pathways [43][44][46][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78]. It is not completely clear how one bacterial protein produces so pleiotropic effect. One plausible explanation is that CagA acts as a scaffolding protein that interacts with a large number of the host regulatory proteins, tethering them into aberrant enzymatic complexes and altering their normal functions [79].

2.2. VacA and Other Virulence Factors

VacA toxin is another virulence factor that plays a major role in tumorigenesis, associated with H. pylori infection. Its name originates from the ability to cause cell vacuolation in cultured eukaryotic cells. VacA has been classified as a pore-forming toxin. Although many toxins can form pores, the amino acid sequence of VacA is not closely resembled sequences of other known bacterial toxins [22][80][81]. The biosynthesis of VacA includes several sequential steps. Following protein translation, the VacA precursor undergoes complex proteolytic cleavage that produces 88 kDa active toxin that either secreted into the extracellular space or retained on the bacterial surface. The secreted VacA protein binds to target cellular membranes, forming an anion-selective membrane channel [82][83].

Multiple functions have been found to be associated with VacA activity, including disruption of the gastric epithelial barrier, interference with antigen presentation, suppression of autophagy and phagocytosis, inhibition of T cells and B cells that are thought to help bacteria to establish persistent infection [84][85][86][87][88]. The ability of VacA to inhibit autophagy and lysosomal degradation facilitates the accumulation of oncogenic protein CagA in gastric epithelial cells [89].

There are considerable variations in VacA sequences. Three main regions of diversity have been recognized in VacA: the signal sequence region (or “s”), the intermediate region (or “i”), and the middle region (or “m”). Based on sequence heterogeneity, the s region was subdivided into s1 (further subdivided into s1a, s1b, and s1c) and s2 types, the i region was subdivided into i1 and i2 types, and the m region was subdivided into m1 and m2 (further subdivided into m2a and m2b) types [85][90]. The incidence of GC has been found to be higher in populations infected with H. pylori variants containing type s1/i1/m1 of vacA, compared to populations infected with H. pylori type s2/i2/m2 of vacA [36][84][85]. Bacterial strains carrying type s1 and m1 vacA alleles have been associated with epithelial damage, increased gastric inflammation, and duodenal ulceration [91][92][93].

Besides CagA and VacA, H. pylori expresses a number of other cancer-associated virulence determinants. Outer-membrane proteins (OMPs) are among them. These proteins are important for bacterial adherence, colonization, survival, and persistence [94]. These factors also promote gastric diseases by affecting the signaling pathways in the host cells, enhancing activity of the T4SS, and altering immune responses [94]. H. pylori expresses a large repertoire of OMPs divided into five major families based on their sequence similarities [95]. The largest and the most studied family is the Family 1, which comprises the Hop (for H. pylori OMP) and Hor (for Hop related) proteins. The two most studied H. pylori adhesins in the Hop subgroup are BabA(HopS) and SabA(HopP), which have been originally identified to interact with the fucosylated-Lewis B (LeB) and the sialylated-Lewis X (sLeX) blood group antigens, respectively, mediating binding of H. pylori to extracellular matrix and gastric epithelial cells [96][97]. BabA potentiates activity of the T4SS [98] and is involved in induction of double-strand breaks in host cells [49]. SabA increases the colonization density and inflammation in human stomach [97][99]. Several studies analyzed associations of BabA and SabA expression with clinical outcome. The BabA status of infecting bacteria has been found to be associated with the presence of intestinal metaplasia, gastric adenocarcinoma, and MALT (Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue) lymphoma [96][100][101][102][103][104]. Similarly, the SabA status was correlated with an increased risk of premalignant lesions and gastric cancer [105][106]; however, some studies produced contradictory results [99][107].

Other OMPs, such as OipA(HopH), HopQ, and HomB, have also been implicated in gastric tumorigenesis [102][108][109][110][111][112][113][114][115]. Further studies are needed to better characterize properties of OMPs and their roles in gastric tumorigenesis.

3. Gastric Microbiota

The stomach is not a sterile organ, despite its high acidity. It is populated by complex gastric microbial communities that affect tumorigenic processes and are important for the maintenance of human health.

The composition of normal gastric microbiota is diverse and highly dynamic with the most abundant phyla: Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Fusobacteria, Actinobacteria, and others [116][117]. On the other hand, H. pylori has been found to be the most prevalent bacteria in the stomach of H. pylori-infected individuals [116][118]. H. pylori can induce profound changes in the composition of gastric microbiota [117][119][120][121][122][123][124][125]. Analyses of gastric microbiota in specific pathogen-free (SPF) mice revealed that H. pylori infection decreases abundance of normal gastric flora, such as Lactobacilli, and increases the presence of Clostridia, Ruminococcus spp., Eubacterium spp., Bacteroides/Prevotella spp., and others [122]. Similar phenomenon was observed in Mongolian gerbils [124][125][126]. These alterations can be explained, at least in part, by physiological changes caused by persistent H. pylori infection [127]. Induction of chronic inflammation and suppression of acid production can facilitate growth of various non–H. pylori bacterial species [127][128][129]. Many aspects of these interactions still remain controversial. Some studies did not find significant differences in the microbial composition between H. pylori–positive and –negative individuals [116][130][131]. It is likely that multiple confounding factors, such as level and type of inflammation, drug treatment (such as treatment with proton pump inhibitors), and the presence of precancerous and cancerous lesions, have to be taken into consideration during analyses of gastric microbiota.

Phylogenetic diversity of the stomach microbiome is changed during progression from gastritis to intestinal metaplasia and GC in human patients [120][132][133][134]. H. pylori colonization of the human stomach is frequently decreased in patients with advanced premalignant and malignant lesions, while abundance of Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, Veillonella, Clostridia, and others is increased [132][133][134][135][136]. Decline in Porphyromonas, Neisseria, and S. sinensis species and concomitant increase in Lactobacillus coleohominis and Lachnospiraceae were found to correlate with progression from gastritis to GC [133]. Changes in the gastric microbiota were also observed after surgical treatment of GC patients [137].

Synergetic interactions of bacteria with H. pylori to promote gastric neoplasia have been convincingly demonstrated by using transgenic insulin–gastrin (INS–GAS) mice [138][139]. It was found that H. pylori infection causes less severe gastric lesions and delayed onset of gastric intraepithelial neoplasms (GINs) in germ-free INS–GAS mice compared to mice with complex gastric microbiota [140]. In another study, infection of INS–GAS mice with restricted Altered Schaedler flora (rASF), containing Clostridium, Lactobacillus, and Bacteroides species, was sufficient to develop gastric dysplasia [141]. Infection with H. pylori further accelerated the onset of gastric lesions in rASF-infected mice [142]. Notably, antimicrobial therapies delayed onset of GIN not only in INS–GAS mice infected with H. pylori, but also in animals without H. pylori infection, thus indicating that non–H. pylori bacteria, including those considered as commensals, may represent an additional GC risk, particularly in H. pylori–infected susceptible individuals. [140][142][143][144].

It is not completely clear how non–H. pylori microbiota synergizes with H. pylori to induce GC. One plausible explanation includes overgrowth of bacteria, converting nitrogen compounds into potentially carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds [129]. It was shown that reduction of gastric acidity causes growth of nitrate-reducing bacteria, which produce carcinogenic N-nitrosamine [128][145][146]. It is also possible that various non–H. pylori bacteria promote sustained inflammation that contributes to development of GC.

Interactions within the gastric microbiome are complex and may result in various outcomes. Colonization of C57BL/6 mice with the enterohepatic Helicobacter species, H. bilis or H. muridarum, before challenge with H. pylori, was found to reduce H. pylori–induced gastric injury [147][148]. Similarly, oral Lactobacillus strains were shown to suppress H. pylori– and H. felis–induced inflammation in both mice and gerbils [125][149][150][151][152]. Consistent with rodent models, certain Lactobacilli were also found to suppress H. pylori growth and gastric mucosal inflammation in human individuals [153][154].

One interesting aspect of complex biological interactions in the stomach is the influence of helminthiasis. Parasitic worms are known to be involved in the development of various human malignancies [155]. However, certain types of helminths can decrease the risk of GC [156][157]. Infection of mice with enteric helminth (Heligmosomoides polygyrus) has been found to attenuate progression of premalignant gastric lesions induced by H. pylori and H. felis [156][158]. It was also suggested that helminths may decrease the incidence of H. pylori-associated GC in certain world populations due to their immunomodulating effects [157][159].

References

- De Martel, C.; Georges, D.; Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Clifford, G.M. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: A worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e180–e190.

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021.

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424.

- Lauren, P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: Diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 1965, 64, 31–49.

- Van Cutsem, E.; Sagaert, X.; Topal, B.; Haustermans, K.; Prenen, H. Gastric cancer. Lancet 2016, 388, 2654–2664.

- Bosman, F.T.; Carneiro, F.; Hruban, R.H.; Theise, N.D. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System, 4th ed.; IARC: Lyon, France, 2010.

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014, 513, 202–209.

- Cristescu, R.; Lee, J.; Nebozhyn, M.; Kim, K.M.; Ting, J.C.; Wong, S.S.; Liu, J.; Yue, Y.G.; Wang, J.; Yu, K.; et al. Molecular analysis of gastric cancer identifies subtypes associated with distinct clinical outcomes. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 449–456.

- Wang, Q.; Liu, G.; Hu, C. Molecular classification of gastric adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterol. Res. 2019, 12, 275–282.

- Warren, J.R.; Marshall, B. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet 1983, 1, 1273–1275.

- Moss, S.F. The clinical evidence linking Helicobacter pylori to gastric cancer. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 3, 183–191.

- Correa, P. A human model of gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1988, 48, 3554–3560.

- IARC working group on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. Lyon, (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum. 1994, 61, 1–241.

- Lee, Y.C.; Chiang, T.H.; Chou, C.K.; Tu, Y.K.; Liao, W.C.; Wu, M.S.; Graham, D.Y. Association between Helicobacter pylori eradication and gastric cancer incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1113–1124.e5.

- Doorakkers, E.; Lagergren, J.; Engstrand, L.; Brusselaers, N. Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment and the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma in a Western population. Gut 2018, 67, 2092–2096.

- Wong, B.C.; Lam, S.K.; Wong, W.M.; Chen, J.S.; Zheng, T.T.; Feng, R.E.; Lai, K.C.; Hu, W.H.; Yuen, S.T.; Leung, S.Y.; et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004, 291, 187–194.

- Zhang, W.; Chen, Q.; Liang, X.; Liu, W.; Xiao, S.; Graham, D.Y.; Lu, H. Bismuth, lansoprazole, amoxicillin and metronidazole or clarithromycin as first-line Helicobacter pylori therapy. Gut 2015, 64, 1715–1720.

- Schmidt, P.H.; Lee, J.R.; Joshi, V.; Playford, R.J.; Poulsom, R.; Wright, N.A.; Goldenring, J.R. Identification of a metaplastic cell lineage associated with human gastric adenocarcinoma. Lab. Investig. 1999, 79, 639–646.

- Saenz, J.B.; Vargas, N.; Mills, J.C. Tropism for spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia allows Helicobacter pylori to expand its intragastric niche. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 160–174.e7.

- Plummer, M.; Franceschi, S.; Vignat, J.; Forman, D.; de Martel, C. Global burden of gastric cancer attributable to Helicobacter pylori. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, 487–490.

- Blaser, M.J.; Perez-Perez, G.I.; Kleanthous, H.; Cover, T.L.; Peek, R.M.; Chyou, P.H.; Stemmermann, G.N.; Nomura, A. Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 2111–2115.

- Naumann, M.; Sokolova, O.; Tegtmeyer, N.; Backert, S. Helicobacter pylori: A paradigm pathogen for subverting host cell signal transmission. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 316–328.

- Abadi, A.T.; Lee, Y.Y. Helicobacter pylori vacA as marker for gastric cancer and gastroduodenal diseases: One but not the only factor. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 4451.

- Lopez-Vidal, Y.; Ponce-de-Leon, S.; Castillo-Rojas, G.; Barreto-Zuniga, R.; Torre-Delgadillo, A. High diversity of vacA and cagA Helicobacter pylori genotypes in patients with and without gastric cancer. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3849.

- Wilson, K.T.; Crabtree, J.E. Immunology of Helicobacter pylori: Insights into the failure of the immune response and perspectives on vaccine studies. Gastroenterology 2007, 133, 288–308.

- Zaika, A.I.; Wei, J.; Noto, J.M.; Peek, R.M. Microbial regulation of p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005099.

- Stein, S.C.; Faber, E.; Bats, S.H.; Murillo, T.; Speidel, Y.; Coombs, N.; Josenhans, C. Helicobacter pylori modulates host cell responses by CagT4SS-dependent translocation of an intermediate metabolite of LPS inner core heptose biosynthesis. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006514.

- Varga, M.G.; Shaffer, C.L.; Sierra, J.C.; Suarez, G.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Whitaker, M.E.; Romero-Gallo, J.; Krishna, U.S.; Delgado, A.; Gomez, M.A.; et al. Pathogenic Helicobacter pylori strains translocate DNA and activate TLR9 via the cancer-associated cag type IV secretion system. Oncogene 2016, 35, 6262–6269.

- Viala, J.; Chaput, C.; Boneca, I.G.; Cardona, A.; Girardin, S.E.; Moran, A.P.; Athman, R.; Memet, S.; Huerre, M.R.; Coyle, A.J.; et al. Nod1 responds to peptidoglycan delivered by the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island. Nat. Immunol. 2004, 5, 1166–1174.

- Naito, M.; Yamazaki, T.; Tsutsumi, R.; Higashi, H.; Onoe, K.; Yamazaki, S.; Azuma, T.; Hatakeyama, M. Influence of EPIYA-repeat polymorphism on the phosphorylation-dependent biological activity of Helicobacter pylori CagA. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 1181–1190.

- Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Gong, Y.; Yuan, Y. Association of CagA EPIYA-D or EPIYA-C phosphorylation sites with peptic ulcer and gastric cancer risks: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2017, 96, e6620.

- Hatakeyama, M. Malignant Helicobacter pylori-associated diseases: Gastric cancer and MALT lymphoma. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1149, 135–149.

- Ren, S.; Higashi, H.; Lu, H.; Azuma, T.; Hatakeyama, M. Structural basis and functional consequence of Helicobacter pylori CagA multimerization in cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 32344–32352.

- Parsonnet, J.; Friedman, G.D.; Orentreich, N.; Vogelman, H. Risk for gastric cancer in people with CagA positive or CagA negative Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut 1997, 40, 297–301.

- Huang, J.Q.; Zheng, G.F.; Sumanac, K.; Irvine, E.J.; Hunt, R.H. Meta-analysis of the relationship between cagA seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology 2003, 125, 1636–1644.

- Matos, J.I.; de Sousa, H.A.; Marcos-Pinto, R.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M. Helicobacter pylori CagA and VacA genotypes and gastric phenotype: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 25, 1431–1441.

- Ohnishi, N.; Yuasa, H.; Tanaka, S.; Sawa, H.; Miura, M.; Matsui, A.; Higashi, H.; Musashi, M.; Iwabuchi, K.; Suzuki, M.; et al. Transgenic expression of Helicobacter pylori CagA induces gastrointestinal and hematopoietic neoplasms in mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1003–1008.

- Neal, J.T.; Peterson, T.S.; Kent, M.L.; Guillemin, K.H. pylori virulence factor CagA increases intestinal cell proliferation by Wnt pathway activation in a transgenic zebrafish model. Dis. Model. Mech. 2013, 6, 802–810.

- Wandler, A.M.; Guillemin, K. Transgenic expression of the Helicobacter pylori virulence factor CagA promotes apoptosis or tumorigenesis through JNK activation in Drosophila. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002939.

- Wei, J.; Nagy, T.A.; Vilgelm, A.; Zaika, E.; Ogden, S.R.; Romero-Gallo, J.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Correa, P.; Washington, M.K.; El-Rifai, W.; et al. Regulation of p53 tumor suppressor by Helicobacter pylori in gastric epithelial cells. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 1333–1343.e4.

- Bhardwaj, V.; Noto, J.M.; Wei, J.; Andl, C.; El-Rifai, W.; Peek, R.M.; Zaika, A.I. Helicobacter pylori bacteria alter the p53 stress response via ERK-HDM2 pathway. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 1531–1543.

- Wei, J.; Noto, J.; Zaika, E.; Romero-Gallo, J.; Correa, P.; El-Rifai, W.; Peek, R.M.; Zaika, A. Pathogenic bacterium Helicobacter pylori alters the expression profile of p53 protein isoforms and p53 response to cellular stresses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E2543–E2550.

- Wei, J.; Noto, J.M.; Zaika, E.; Romero-Gallo, J.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Schneider, B.; El-Rifai, W.; Correa, P.; Peek, R.M.; Zaika, A.I. Bacterial CagA protein induces degradation of p53 protein in a p14ARF-dependent manner. Gut 2015, 64, 1040–1048.

- Horvat, A.; Noto, J.M.; Ramatchandirin, B.; Zaika, E.; Palrasu, M.; Wei, J.; Schneider, B.G.; El-Rifai, W.; Peek, R.M., Jr.; Zaika, A.I. Helicobacter pylori pathogen regulates p14ARF tumor suppressor and autophagy in gastric epithelial cells. Oncogene 2018, 37, 5054–5065.

- Eguchi, H.; Herschenhous, N.; Kuzushita, N.; Moss, S.F. Helicobacter pylori increases proteasome-mediated degradation of p27(kip1) in gastric epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 4739–4746.

- Palrasu, M.; Zaika, E.; El-Rifai, W.; Garcia-Buitrago, M.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Wilson, K.T.; Peek, R.M., Jr.; Zaika, A.I. Bacterial CagA protein compromises tumor suppressor mechanisms in gastric epithelial cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 2422–2434.

- Koeppel, M.; Garcia-Alcalde, F.; Glowinski, F.; Schlaermann, P.; Meyer, T.F. Helicobacter pylori infection causes characteristic DNA damage patterns in human cells. Cell Rep. 2015, 11, 1703–1713.

- Papa, A.; Danese, S.; Sgambato, A.; Ardito, R.; Zannoni, G.; Rinelli, A.; Vecchio, F.M.; Gentiloni-Silveri, N.; Cittadini, A.; Gasbarrini, G.; et al. Role of Helicobacter pylori CagA+ infection in determining oxidative DNA damage in gastric mucosa. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 37, 409–413.

- Toller, I.M.; Neelsen, K.J.; Steger, M.; Hartung, M.L.; Hottiger, M.O.; Stucki, M.; Kalali, B.; Gerhard, M.; Sartori, A.A.; Lopes, M.; et al. Carcinogenic bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori triggers DNA double-strand breaks and a DNA damage response in its host cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 14944–14949.

- Tsugawa, H.; Suzuki, H.; Saya, H.; Hatakeyama, M.; Hirayama, T.; Hirata, K.; Nagano, O.; Matsuzaki, J.; Hibi, T. Reactive oxygen species-induced autophagic degradation of Helicobacter pylori CagA is specifically suppressed in cancer stem-like cells. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 12, 764–777.

- Hanada, K.; Uchida, T.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Watada, M.; Yamaguchi, N.; Yamamoto, K.; Shiota, S.; Moriyama, M.; Graham, D.Y.; Yamaoka, Y. Helicobacter pylori infection introduces DNA double-strand breaks in host cells. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 4182–4189.

- Hartung, M.L.; Gruber, D.C.; Koch, K.N.; Gruter, L.; Rehrauer, H.; Tegtmeyer, N.; Backert, S.; Muller, A.H. pylori-Induced DNA strand breaks are introduced by nucleotide excision repair endonucleases and promote NF-kappaB target gene expression. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 70–79.

- Raza, Y.; Khan, A.; Farooqui, A.; Mubarak, M.; Facista, A.; Akhtar, S.S.; Khan, S.; Kazi, J.I.; Bernstein, C.; Kazmi, S.U. Oxidative DNA damage as a potential early biomarker of Helicobacter pylori associated carcinogenesis. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2014, 20, 839–846.

- Uehara, T.; Ma, D.; Yao, Y.; Lynch, J.P.; Morales, K.; Ziober, A.; Feldman, M.; Ota, H.; Sepulveda, A.R. H. pylori infection is associated with DNA damage of Lgr5-positive epithelial stem cells in the stomach of patients with gastric cancer. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2013, 58, 140–149.

- Xie, C.; Xu, L.Y.; Yang, Z.; Cao, X.M.; Li, W.; Lu, N.H. Expression of gammaH2AX in various gastric pathologies and its association with Helicobacter pylori infection. Oncol. Lett. 2014, 7, 159–163.

- Zamperone, A.; Cohen, D.; Stein, M.; Viard, C.; Musch, A. Inhibition of polarity-regulating kinase PAR1b contributes to Helicobacter pylori inflicted DNA Double Strand Breaks in gastric cells. Cell Cycle 2019, 18, 299–311.

- Machado, A.M.; Desler, C.; Boggild, S.; Strickertsson, J.A.; Friis-Hansen, L.; Figueiredo, C.; Seruca, R.; Rasmussen, L.J. Helicobacter pylori infection affects mitochondrial function and DNA repair, thus, mediating genetic instability in gastric cells. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2013, 134, 460–466.

- Kim, J.J.; Tao, H.; Carloni, E.; Leung, W.K.; Graham, D.Y.; Sepulveda, A.R. Helicobacter pylori impairs DNA mismatch repair in gastric epithelial cells. Gastroenterology 2002, 123, 542–553.

- Machado, A.M.; Figueiredo, C.; Touati, E.; Maximo, V.; Sousa, S.; Michel, V.; Carneiro, F.; Nielsen, F.C.; Seruca, R.; Rasmussen, L.J. Helicobacter pylori infection induces genetic instability of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in gastric cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 2995–3002.

- Park, D.I.; Park, S.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.W.; Cho, Y.K.; Kim, H.J.; Sohn, C.I.; Jeon, W.K.; Kim, B.I.; Cho, E.Y.; et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori infection on the expression of DNA mismatch repair protein. Helicobacter 2005, 10, 179–184.

- Strickertsson, J.A.; Desler, C.; Rasmussen, L.J. Impact of bacterial infections on aging and cancer: Impairment of DNA repair and mitochondrial function of host cells. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 56, 164–174.

- Vallejo-Flores, G.; Torres, J.; Sandoval-Montes, C.; Arevalo-Romero, H.; Meza, I.; Camorlinga-Ponce, M.; Torres-Morales, J.; Chavez-Rueda, A.K.; Legorreta-Haquet, M.V.; Fuentes-Panana, E.M. Helicobacter pylori CagA suppresses apoptosis through activation of AKT in a nontransformed epithelial cell model of glandular acini formation. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 761501.

- Lin, W.C.; Tsai, H.F.; Kuo, S.H.; Wu, M.S.; Lin, C.W.; Hsu, P.I.; Cheng, A.L.; Hsu, P.N. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into Human B lymphocytes, the origin of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 5740–5748.

- Mimuro, H.; Suzuki, T.; Nagai, S.; Rieder, G.; Suzuki, M.; Nagai, T.; Fujita, Y.; Nagamatsu, K.; Ishijima, N.; Koyasu, S.; et al. Helicobacter pylori dampens gut epithelial self-renewal by inhibiting apoptosis, a bacterial strategy to enhance colonization of the stomach. Cell Host Microbe 2007, 2, 250–263.

- Noto, J.M.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Chaturvedi, R.; Bartel, C.A.; Thatcher, E.J.; Delgado, A.; Romero-Gallo, J.; Wilson, K.T.; Correa, P.; Patton, J.G.; et al. Strain-specific suppression of microRNA-320 by carcinogenic Helicobacter pylori promotes expression of the antiapoptotic protein Mcl-1. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2013, 305, G786–G796.

- Abu-Taleb, A.M.F.; Abdelattef, R.S.; Abdel-Hady, A.A.; Omran, F.H.; El-Korashi, L.A.; Abdel-Aziz El-Hady, H.; El-Gebaly, A.M. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori cagA and iceA genes and their association with gastrointestinal diseases. Int. J. Microbiol. 2018, 2018, 4809093.

- Peek, R.M., Jr.; Blaser, M.J. Pathophysiology of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. Am. J. Med. 1997, 102, 200–207.

- Figura, N.; Vindigni, C.; Covacci, A.; Presenti, L.; Burroni, D.; Vernillo, R.; Banducci, T.; Roviello, F.; Marrelli, D.; Biscontri, M.; et al. cagA positive and negative Helicobacter pylori strains are simultaneously present in the stomach of most patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia: Relevance to histological damage. Gut 1998, 42, 772–778.

- Li, N.; Tang, B.; Jia, Y.P.; Zhu, P.; Zhuang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, K.; Zhang, W.J.; Guo, G.; et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein negatively regulates autophagy and promotes inflammatory response via c-Met-PI3K/Akt-mTOR signaling pathway. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 417.

- Yamaoka, Y.; Kita, M.; Kodama, T.; Sawai, N.; Kashima, K.; Imanishi, J. Induction of various cytokines and development of severe mucosal inflammation by cagA gene positive Helicobacter pylori strains. Gut 1997, 41, 442–451.

- Wei, J.; O’Brien, D.; Vilgelm, A.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Correa, P.; Washington, M.K.; El-Rifai, W.; Peek, R.M.; Zaika, A. Interaction of Helicobacter pylori with gastric epithelial cells is mediated by the p53 protein family. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 1412–1423.

- Bauer, B.; Pang, E.; Holland, C.; Kessler, M.; Bartfeld, S.; Meyer, T.F. The Helicobacter pylori virulence effector CagA abrogates human beta-defensin 3 expression via inactivation of EGFR signaling. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 11, 576–586.

- Higashi, H.; Nakaya, A.; Tsutsumi, R.; Yokoyama, K.; Fujii, Y.; Ishikawa, S.; Higuchi, M.; Takahashi, A.; Kurashima, Y.; Teishikata, Y.; et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA induces Ras-independent morphogenetic response through SHP-2 recruitment and activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 17205–17216.

- Mueller, D.; Tegtmeyer, N.; Brandt, S.; Yamaoka, Y.; De Poire, E.; Sgouras, D.; Wessler, S.; Torres, J.; Smolka, A.; Backert, S. c-Src and c-Abl kinases control hierarchic phosphorylation and function of the CagA effector protein in Western and East Asian Helicobacter pylori strains. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 1553–1566.

- Tabassam, F.H.; Graham, D.Y.; Yamaoka, Y. Helicobacter pylori activate epidermal growth factor receptor- and phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase-dependent Akt and glycogen synthase kinase 3beta phosphorylation. Cell. Microbiol. 2009, 11, 70–82.

- Tegtmeyer, N.; Hartig, R.; Delahay, R.M.; Rohde, M.; Brandt, S.; Conradi, J.; Takahashi, S.; Smolka, A.J.; Sewald, N.; Backert, S. A small fibronectin-mimicking protein from bacteria induces cell spreading and focal adhesion formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 23515–23526.

- Tegtmeyer, N.; Wittelsberger, R.; Hartig, R.; Wessler, S.; Martinez-Quiles, N.; Backert, S. Serine phosphorylation of cortactin controls focal adhesion kinase activity and cell scattering induced by Helicobacter pylori. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 9, 520–531.

- Tsutsumi, R.; Takahashi, A.; Azuma, T.; Higashi, H.; Hatakeyama, M. Focal adhesion kinase is a substrate and downstream effector of SHP-2 complexed with Helicobacter pylori CagA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 261–276.

- Hatakeyama, M. Structure and function of Helicobacter pylori CagA, the first-identified bacterial protein involved in human cancer. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2017, 93, 196–219.

- Torres, V.J.; Ivie, S.E.; McClain, M.S.; Cover, T.L. Functional properties of the p33 and p55 domains of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 21107–21114.

- Wang, W.C.; Wang, H.J.; Kuo, C.H. Two distinctive cell binding patterns by vacuolating toxin fused with glutathione S-transferase: One high-affinity m1-specific binding and the other lower-affinity binding for variant m forms. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 11887–11896.

- Czajkowsky, D.M.; Iwamoto, H.; Cover, T.L.; Shao, Z. The vacuolating toxin from Helicobacter pylori forms hexameric pores in lipid bilayers at low pH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 2001–2006.

- Tombola, F.; Carlesso, C.; Szabo, I.; de Bernard, M.; Reyrat, J.M.; Telford, J.L.; Rappuoli, R.; Montecucco, C.; Papini, E.; Zoratti, M. Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin forms anion-selective channels in planar lipid bilayers: Possible implications for the mechanism of cellular vacuolation. Biophys. J. 1999, 76, 1401–1409.

- Pyburn, T.M.; Foegeding, N.J.; Gonzalez-Rivera, C.; McDonald, N.A.; Gould, K.L.; Cover, T.L.; Ohi, M.D. Structural organization of membrane-inserted hexamers formed by Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin. Mol. Microbiol. 2016, 102, 22–36.

- Atherton, J.C.; Cao, P.; Peek, R.M., Jr.; Tummuru, M.K.; Blaser, M.J.; Cover, T.L. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. Association of specific vacA types with cytotoxin production and peptic ulceration. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 17771–17777.

- Boncristiano, M.; Paccani, S.R.; Barone, S.; Ulivieri, C.; Patrussi, L.; Ilver, D.; Amedei, A.; D’Elios, M.M.; Telford, J.L.; Baldari, C.T. The Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin inhibits T cell activation by two independent mechanisms. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 1887–1897.

- Gebert, B.; Fischer, W.; Weiss, E.; Hoffmann, R.; Haas, R. Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin inhibits T lymphocyte activation. Science 2003, 301, 1099–1102.

- Sundrud, M.S.; Torres, V.J.; Unutmaz, D.; Cover, T.L. Inhibition of primary human T cell proliferation by Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin (VacA) is independent of VacA effects on IL-2 secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 7727–7732.

- Abdullah, M.; Greenfield, L.K.; Bronte-Tinkew, D.; Capurro, M.I.; Rizzuti, D.; Jones, N.L. VacA promotes CagA accumulation in gastric epithelial cells during Helicobacter pylori infection. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 38.

- Van Doorn, L.J.; Figueiredo, C.; Sanna, R.; Pena, S.; Midolo, P.; Ng, E.K.; Atherton, J.C.; Blaser, M.J.; Quint, W.G. Expanding allelic diversity of Helicobacter pylori vacA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998, 36, 2597–2603.

- Atherton, J.C.; Peek, R.M., Jr.; Tham, K.T.; Cover, T.L.; Blaser, M.J. Clinical and pathological importance of heterogeneity in vacA, the vacuolating cytotoxin gene of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology 1997, 112, 92–99.

- Sinnett, C.G.; Letley, D.P.; Narayanan, G.L.; Patel, S.R.; Hussein, N.R.; Zaitoun, A.M.; Robinson, K.; Atherton, J.C. Helicobacter pylori vacA transcription is genetically-determined and stratifies the level of human gastric inflammation and atrophy. J. Clin. Pathol. 2016, 69, 968–973.

- Van Doorn, L.J.; Figueiredo, C.; Sanna, R.; Plaisier, A.; Schneeberger, P.; de Boer, W.; Quint, W. Clinical relevance of the cagA, vacA, and iceA status of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology 1998, 115, 58–66.

- Kao, C.Y.; Sheu, B.S.; Wu, J.J. Helicobacter pylori infection: An overview of bacterial virulence factors and pathogenesis. Biomed. J. 2016, 39, 14–23.

- Alm, R.A.; Bina, J.; Andrews, B.M.; Doig, P.; Hancock, R.E.; Trust, T.J. Comparative genomics of Helicobacter pylori: Analysis of the outer membrane protein families. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 4155–4168.

- Fujimoto, S.; Olaniyi Ojo, O.; Arnqvist, A.; Wu, J.Y.; Odenbreit, S.; Haas, R.; Graham, D.Y.; Yamaoka, Y. Helicobacter pylori BabA expression, gastric mucosal injury, and clinical outcome. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 5, 49–58.

- Mahdavi, J.; Sonden, B.; Hurtig, M.; Olfat, F.O.; Forsberg, L.; Roche, N.; Angstrom, J.; Larsson, T.; Teneberg, S.; Karlsson, K.A.; et al. Helicobacter pylori SabA adhesin in persistent infection and chronic inflammation. Science 2002, 297, 573–578.

- Ishijima, N.; Suzuki, M.; Ashida, H.; Ichikawa, Y.; Kanegae, Y.; Saito, I.; Boren, T.; Haas, R.; Sasakawa, C.; Mimuro, H. BabA-mediated adherence is a potentiator of the Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion system activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 25256–25264.

- Sheu, B.S.; Odenbreit, S.; Hung, K.H.; Liu, C.P.; Sheu, S.M.; Yang, H.B.; Wu, J.J. Interaction between host gastric Sialyl-Lewis X and H. pylori SabA enhances H. pylori density in patients lacking gastric Lewis B antigen. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 101, 36–44.

- Azevedo, M.; Eriksson, S.; Mendes, N.; Serpa, J.; Figueiredo, C.; Resende, L.P.; Ruvoen-Clouet, N.; Haas, R.; Boren, T.; Le Pendu, J.; et al. Infection by Helicobacter pylori expressing the BabA adhesin is influenced by the secretor phenotype. J. Pathol. 2008, 215, 308–316.

- Gerhard, M.; Lehn, N.; Neumayer, N.; Boren, T.; Rad, R.; Schepp, W.; Miehlke, S.; Classen, M.; Prinz, C. Clinical relevance of the Helicobacter pylori gene for blood-group antigen-binding adhesin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 12778–12783.

- Su, Y.L.; Huang, H.L.; Huang, B.S.; Chen, P.C.; Chen, C.S.; Wang, H.L.; Lin, P.H.; Chieh, M.S.; Wu, J.J.; Yang, J.C.; et al. Combination of OipA, BabA, and SabA as candidate biomarkers for predicting Helicobacter pylori-related gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36442.

- Yu, J.; Leung, W.K.; Go, M.Y.; Chan, M.C.; To, K.F.; Ng, E.K.; Chan, F.K.; Ling, T.K.; Chung, S.C.; Sung, J.J. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori babA2 status with gastric epithelial cell turnover and premalignant gastric lesions. Gut 2002, 51, 480–484.

- Prinz, C.; Schoniger, M.; Rad, R.; Becker, I.; Keiditsch, E.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Classen, M.; Rosch, T.; Schepp, W.; Gerhard, M. Key importance of the Helicobacter pylori adherence factor blood group antigen binding adhesin during chronic gastric inflammation. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 1903–1909.

- Lehours, P.; Menard, A.; Dupouy, S.; Bergey, B.; Richy, F.; Zerbib, F.; Ruskone-Fourmestraux, A.; Delchier, J.C.; Megraud, F. Evaluation of the association of nine Helicobacter pylori virulence factors with strains involved in low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 880–888.

- Yamaoka, Y.; Ojo, O.; Fujimoto, S.; Odenbreit, S.; Haas, R.; Gutierrez, O.; El-Zimaity, H.M.; Reddy, R.; Arnqvist, A.; Graham, D.Y. Helicobacter pylori outer membrane proteins and gastroduodenal disease. Gut 2006, 55, 775–781.

- Chen, M.Y.; He, C.Y.; Meng, X.; Yuan, Y. Association of Helicobacter pylori babA2 with peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 4242–4251.

- Zhao, Q.; Song, C.; Wang, K.; Li, D.; Yang, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, L.; Zhou, N.; Xie, Y. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori babA, oipA, sabA, and homB genes in isolates from Chinese patients with different gastroduodenal diseases. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2020, 209, 565–577.

- Bartpho, T.S.; Wattanawongdon, W.; Tongtawee, T.; Paoin, C.; Kangwantas, K.; Dechsukhum, C. Precancerous gastric lesions with Helicobacter pylori vacA (+)/babA2(+)/oipA (+) genotype increase the risk of gastric cancer. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 7243029.

- Liu, J.; He, C.; Chen, M.; Wang, Z.; Xing, C.; Yuan, Y. Association of presence/absence and on/off patterns of Helicobacter pylori oipA gene with peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer risks: A meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 555.

- Cao, P.; Lee, K.J.; Blaser, M.J.; Cover, T.L. Analysis of hopQ alleles in East Asian and Western strains of Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2005, 251, 37–43.

- Leylabadlo, H.E.; Yekani, M.; Ghotaslou, R. Helicobacter pylori hopQ alleles (type I and II) in gastric cancer. Biomed. Rep. 2016, 4, 601–604.

- Jung, S.W.; Sugimoto, M.; Graham, D.Y.; Yamaoka, Y. homB status of Helicobacter pylori as a novel marker to distinguish gastric cancer from duodenal ulcer. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 3241–3245.

- Kang, J.; Jones, K.R.; Jang, S.; Olsen, C.H.; Yoo, Y.J.; Merrell, D.S.; Cha, J.H. The geographic origin of Helicobacter pylori influences the association of the homB gene with gastric cancer. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 1082–1085.

- Abadi, A.T.B.; Rafiei, A.; Ajami, A.; Hosseini, V.; Taghvaei, T.; Jones, K.R.; Merrell, D.S. Helicobacter pylori homB, but not cagA, is associated with gastric cancer in Iran. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 3191–3197.

- Bik, E.M.; Eckburg, P.B.; Gill, S.R.; Nelson, K.E.; Purdom, E.A.; Francois, F.; Perez-Perez, G.; Blaser, M.J.; Relman, D.A. Molecular analysis of the bacterial microbiota in the human stomach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 732–737.

- Li, X.X.; Wong, G.L.; To, K.F.; Wong, V.W.; Lai, L.H.; Chow, D.K.; Lau, J.Y.; Sung, J.J.; Ding, C. Bacterial microbiota profiling in gastritis without Helicobacter pylori infection or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7985.

- Andersson, A.F.; Lindberg, M.; Jakobsson, H.; Backhed, F.; Nyren, P.; Engstrand, L. Comparative analysis of human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2836.

- Espinoza, J.L.; Matsumoto, A.; Tanaka, H.; Matsumura, I. Gastric microbiota: An emerging player in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric malignancies. Cancer Lett. 2018, 414, 147–152.

- Coker, O.O.; Dai, Z.; Nie, Y.; Zhao, G.; Cao, L.; Nakatsu, G.; Wu, W.K.; Wong, S.H.; Chen, Z.; Sung, J.J.Y.; et al. Mucosal microbiome dysbiosis in gastric carcinogenesis. Gut 2018, 67, 1024–1032.

- Chen, X.H.; Wang, A.; Chu, A.N.; Gong, Y.H.; Yuan, Y. Mucosa-associated microbiota in gastric cancer tissues compared with non-cancer tissues. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1261.

- Aebischer, T.; Fischer, A.; Walduck, A.; Schlotelburg, C.; Lindig, M.; Schreiber, S.; Meyer, T.F.; Bereswill, S.; Gobel, U.B. Vaccination prevents Helicobacter pylori-induced alterations of the gastric flora in mice. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 46, 221–229.

- Maldonado-Contreras, A.; Goldfarb, K.C.; Godoy-Vitorino, F.; Karaoz, U.; Contreras, M.; Blaser, M.J.; Brodie, E.L.; Dominguez-Bello, M.G. Structure of the human gastric bacterial community in relation to Helicobacter pylori status. ISME J. 2011, 5, 574–579.

- Noto, J.M.; Rose, K.L.; Hachey, A.J.; Delgado, A.G.; Romero-Gallo, J.; Wroblewski, L.E.; Schneider, B.G.; Shah, S.C.; Cover, T.L.; Wilson, K.T.; et al. Carcinogenic Helicobacter pylori strains selectively dysregulate the in vivo gastric proteome, which may be associated with stomach cancer progression. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2019, 18, 352–371.

- Osaki, T.; Matsuki, T.; Asahara, T.; Zaman, C.; Hanawa, T.; Yonezawa, H.; Kurata, S.; Woo, T.D.; Nomoto, K.; Kamiya, S. Comparative analysis of gastric bacterial microbiota in Mongolian gerbils after long-term infection with Helicobacter pylori. Microb. Pathog. 2012, 53, 12–18.

- Sun, Y.Q.; Monstein, H.J.; Nilsson, L.E.; Petersson, F.; Borch, K. Profiling and identification of eubacteria in the stomach of Mongolian gerbils with and without Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 2003, 8, 149–157.

- Blaser, M.J.; Atherton, J.C. Helicobacter pylori persistence: Biology and disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 113, 321–333.

- Sanduleanu, S.; Jonkers, D.; De Bruine, A.; Hameeteman, W.; Stockbrugger, R.W. Non-Helicobacter pylori bacterial flora during acid-suppressive therapy: Differential findings in gastric juice and gastric mucosa. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 15, 379–388.

- Mowat, C.; Williams, C.; Gillen, D.; Hossack, M.; Gilmour, D.; Carswell, A.; Wirz, A.; Preston, T.; McColl, K.E. Omeprazole, Helicobacter pylori status, and alterations in the intragastric milieu facilitating bacterial N-nitrosation. Gastroenterology 2000, 119, 339–347.

- Khosravi, Y.; Dieye, Y.; Poh, B.H.; Ng, C.G.; Loke, M.F.; Goh, K.L.; Vadivelu, J. Culturable bacterial microbiota of the stomach of Helicobacter pylori positive and negative gastric disease patients. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 610421.

- Tan, M.P.; Kaparakis, M.; Galic, M.; Pedersen, J.; Pearse, M.; Wijburg, O.L.; Janssen, P.H.; Strugnell, R.A. Chronic Helicobacter pylori infection does not significantly alter the microbiota of the murine stomach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 1010–1013.

- Eun, C.S.; Kim, B.K.; Han, D.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, K.M.; Choi, B.Y.; Song, K.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, J.F. Differences in gastric mucosal microbiota profiling in patients with chronic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and gastric cancer using pyrosequencing methods. Helicobacter 2014, 19, 407–416.

- Aviles-Jimenez, F.; Vazquez-Jimenez, F.; Medrano-Guzman, R.; Mantilla, A.; Torres, J. Stomach microbiota composition varies between patients with non-atrophic gastritis and patients with intestinal type of gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4202.

- Ferreira, R.M.; Pereira-Marques, J.; Pinto-Ribeiro, I.; Costa, J.L.; Carneiro, F.; Machado, J.C.; Figueiredo, C. Gastric microbial community profiling reveals a dysbiotic cancer-associated microbiota. Gut 2018, 67, 226–236.

- Dicksved, J.; Lindberg, M.; Rosenquist, M.; Enroth, H.; Jansson, J.K.; Engstrand, L. Molecular characterization of the stomach microbiota in patients with gastric cancer and in controls. J. Med. Microbiol. 2009, 58, 509–516.

- Liu, X.; Shao, L.; Liu, X.; Ji, F.; Mei, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, F.; Yan, C.; Li, L.; Ling, Z. Alterations of gastric mucosal microbiota across different stomach microhabitats in a cohort of 276 patients with gastric cancer. EBioMedicine 2019, 40, 336–348.

- Tseng, C.H.; Lin, J.T.; Ho, H.J.; Lai, Z.L.; Wang, C.B.; Tang, S.L.; Wu, C.Y. Gastric microbiota and predicted gene functions are altered after subtotal gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20701.

- Fox, J.G.; Li, X.; Cahill, R.J.; Andrutis, K.; Rustgi, A.K.; Odze, R.; Wang, T.C. Hypertrophic gastropathy in Helicobacter felis-infected wild-type C57BL/6 mice and p53 hemizygous transgenic mice. Gastroenterology 1996, 110, 155–166.

- Fox, J.G.; Rogers, A.B.; Ihrig, M.; Taylor, N.S.; Whary, M.T.; Dockray, G.; Varro, A.; Wang, T.C. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastric cancer in INS-GAS mice is gender specific. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 942–950.

- Lofgren, J.L.; Whary, M.T.; Ge, Z.; Muthupalani, S.; Taylor, N.S.; Mobley, M.; Potter, A.; Varro, A.; Eibach, D.; Suerbaum, S.; et al. Lack of commensal flora in Helicobacter pylori-infected INS-GAS mice reduces gastritis and delays intraepithelial neoplasia. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 210–220.e4.

- Lertpiriyapong, K.; Whary, M.T.; Muthupalani, S.; Lofgren, J.L.; Gamazon, E.R.; Feng, Y.; Ge, Z.; Wang, T.C.; Fox, J.G. Gastric colonisation with a restricted commensal microbiota replicates the promotion of neoplastic lesions by diverse intestinal microbiota in the Helicobacter pylori INS-GAS mouse model of gastric carcinogenesis. Gut 2014, 63, 54–63.

- Lee, C.W.; Rickman, B.; Rogers, A.B.; Muthupalani, S.; Takaishi, S.; Yang, P.; Wang, T.C.; Fox, J.G. Combination of sulindac and antimicrobial eradication of Helicobacter pylori prevents progression of gastric cancer in hypergastrinemic INS-GAS mice. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 8166–8174.

- Lee, C.W.; Rickman, B.; Rogers, A.B.; Ge, Z.; Wang, T.C.; Fox, J.G. Helicobacter pylori eradication prevents progression of gastric cancer in hypergastrinemic INS-GAS mice. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 3540–3548.

- Rolig, A.S.; Cech, C.; Ahler, E.; Carter, J.E.; Ottemann, K.M. The degree of Helicobacter pylori-triggered inflammation is manipulated by preinfection host microbiota. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 1382–1389.

- Leach, S.A.; Thompson, M.; Hill, M. Bacterially catalysed N-nitrosation reactions and their relative importance in the human stomach. Carcinogenesis 1987, 8, 1907–1912.

- Stockbruegger, R.W. Bacterial overgrowth as a consequence of reduced gastric acidity. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 1985, 111, 7–16.

- Lemke, L.B.; Ge, Z.; Whary, M.T.; Feng, Y.; Rogers, A.B.; Muthupalani, S.; Fox, J.G. Concurrent Helicobacter bilis infection in C57BL/6 mice attenuates proinflammatory H. pylori-induced gastric pathology. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 2147–2158.

- Ge, Z.; Feng, Y.; Muthupalani, S.; Eurell, L.L.; Taylor, N.S.; Whary, M.T.; Fox, J.G. Coinfection with Enterohepatic Helicobacter species can ameliorate or promote Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric pathology in C57BL/6 mice. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 3861–3871.

- Chen, Y.H.; Tsai, W.H.; Wu, H.Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Yeh, W.L.; Chen, Y.H.; Hsu, H.Y.; Chen, W.W.; Chen, Y.W.; Chang, W.W.; et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus spp. act against Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 90.

- Kabir, A.M.; Aiba, Y.; Takagi, A.; Kamiya, S.; Miwa, T.; Koga, Y. Prevention of Helicobacter pylori infection by lactobacilli in a gnotobiotic murine model. Gut 1997, 41, 49–55.

- Zaman, C.; Osaki, T.; Hanawa, T.; Yonezawa, H.; Kurata, S.; Kamiya, S. Analysis of the microbial ecology between Helicobacter pylori and the gastric microbiota of Mongolian gerbils. J. Med. Microbiol. 2014, 63, 129–137.

- Schmitz, J.M.; Durham, C.G.; Schoeb, T.R.; Soltau, T.D.; Wolf, K.J.; Tanner, S.M.; McCracken, V.J.; Lorenz, R.G. Helicobacter felis—Associated gastric disease in microbiota-restricted mice. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2011, 59, 826–841.

- Sakamoto, I.; Igarashi, M.; Kimura, K.; Takagi, A.; Miwa, T.; Koga, Y. Suppressive effect of Lactobacillus gasseri OLL 2716 (LG21) on Helicobacter pylori infection in humans. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001, 47, 709–710.

- De Klerk, N.; Maudsdotter, L.; Gebreegziabher, H.; Saroj, S.D.; Eriksson, B.; Eriksson, O.S.; Roos, S.; Linden, S.; Sjolinder, H.; Jonsson, A.B. Lactobacilli reduce Helicobacter pylori attachment to host gastric epithelial cells by inhibiting adhesion gene expression. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 1526–1535.

- Scholte, L.L.S.; Pascoal-Xavier, M.A.; Nahum, L.A. Helminths and cancers from the evolutionary perspective. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 90.

- Fox, J.G.; Beck, P.; Dangler, C.A.; Whary, M.T.; Wang, T.C.; Shi, H.N.; Nagler-Anderson, C. Concurrent enteric helminth infection modulates inflammation and gastric immune responses and reduces helicobacter-induced gastric atrophy. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 536–542.

- Whary, M.T.; Sundina, N.; Bravo, L.E.; Correa, P.; Quinones, F.; Caro, F.; Fox, J.G. Intestinal helminthiasis in Colombian children promotes a Th2 response to Helicobacter pylori: Possible implications for gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2005, 14, 1464–1469.

- Whary, M.T.; Muthupalani, S.; Ge, Z.; Feng, Y.; Lofgren, J.; Shi, H.N.; Taylor, N.S.; Correa, P.; Versalovic, J.; Wang, T.C.; et al. Helminth co-infection in Helicobacter pylori infected INS-GAS mice attenuates gastric premalignant lesions of epithelial dysplasia and glandular atrophy and preserves colonization resistance of the stomach to lower bowel microbiota. Microbes Infect. 2014, 16, 345–355.

- Fuenmayor-Boscan, A.; Hernandez-Rincon, I.; Arismendi-Morillo, G.; Mengual, E.; Rivero, Z.; Romero, G.; Lizarzabal, M.; Alvarez-Mon, M. Changes in the severity of gastric mucosal inflammation associated with Helicobacter pylori in humans coinfected with intestinal helminths. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 39, 186–195.