| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Parvaiz Yousuf | + 3213 word(s) | 3213 | 2021-05-07 10:32:47 | | | |

| 2 | Karina Chen | Meta information modification | 3213 | 2021-05-10 08:36:00 | | |

Video Upload Options

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs) are aggressive diseases with a dismal patient prognosis. Despite significant advances in treatment modalities, the five-year survival rate in patients with HNSCC has improved marginally and therefore warrants a comprehensive understanding of the HNSCC biology. Alterations in the cellular and non-cellular components of the HNSCC tumor micro-environment (TME) play a critical role in regulating many hallmarks of cancer development including evasion of apoptosis, activation of invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, response to therapy, immune escape mechanisms, deregulation of energetics, and therefore the development of an overall aggressive HNSCC phenotype. Cytokines and chemokines are small secretory proteins produced by neoplastic or stromal cells, controlling complex and dynamic cell–cell interactions in the TME to regulate many cancer hallmarks.

1. Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is a very aggressive disease with a dismal prognosis. With an annual incidence of ~800,000 new cases and 350,000 deaths worldwide, HNSCC is the sixth most common cancer globally [1]. HNSCC includes tumors of the oral cavity, hypopharynx, oropharynx, larynx and, paranasal sinuses and is clinically, pathologically, phenotypically, and biologically a heterogeneous disease [2]. Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), being the primary subtype of HNSCC, accounts for two-thirds of the cases occurring in developing nations. Although tobacco and alcohol consumption account for nearly 75% of the total HNSCC cases, there has been a recent rise in the incidence of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) associated oropharynx cancers (OPC) [3]. Cytokines and chemokines are soluble, low molecular weight secretory proteins, which regulate lymphoid tissue development, immune and inflammatory responses by controlling immune cell growth, differentiation, and activation [4][5]. While the cytokines are non-structural, pleiotropic proteins or glycoproteins, which have a complex regulatory influence on inflammation and immunity, chemokines are a large family of low molecular weight (8–14 KDa) heparin-binding chemotactic cytokines that regulate leukocyte trafficking, development, angiogenesis, and hematopoiesis [4][5]. Based on the variations in the structural motif of the first two closely paired and highly conserved cysteine residues, chemokines are divided into CXC, CC, CX3C, and the C subfamilies. While the C subfamily has only two cysteine residues, CXC, CC, and CX3C have four cysteine residues [6]. The letter ‘‘L” followed by a number denotes a specific chemokine (e.g., CCL2 or CXCL8). The receptors are labeled by the letter R followed by the number (e.g., CCR2 or CXCR1) [7][8]. Based on the conserved glutamic acid-leucine-arginine “Glu-Leu-Arg” (ELR) motif at the NH2 terminus, the CXC chemokine family is further subdivided into ELR+ve and ELR−ve. The ELR+ve CXC chemokines are angiogenic and activate CXCR2 mediated signaling pathway in endothelial cells, while the ELR−ve CXC chemokines are angio-static and are potent chemo-attractants for mononuclear leukocytes [9][10][11]. Cytokines such as TNF (α and β), interleukin 1 family (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1 receptor antagonistic (IL-Ira) and IL-2, IL -6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-11, IL-12, IL-15, IL-16, IL -17, IL-18, IL-19, IL-20, IL-21, IL-22, IL-23, IL-24, interferon’s (α, β, and γ), TGFβ, are produced by various types of cell including mononuclear phagocytic cells, T-lymphocytes, B-lymphocytes, Langerhans cells, polymorph nuclear neutrophils (PMNs), and mast cells [12]. Based on their biological properties, these cytokines are classified into T-helper 1 (Th1), T-helper 2 (Th2), and T-helper 17 (Th17) [13]. While Th1 and Th2 cytokines stimulate cellular and humoral immune responses, Th17 cytokines are known to regulate inflammatory responses and autoimmunity [13].

2. HNSCC Tumor Microenvironment

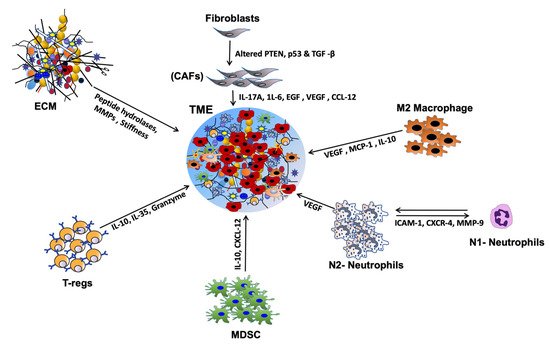

The HNSCC TME is a heterogeneous complex of cellular and non-cellular components that dictate aberrant tissue function and promote the development of aggressive tumors [14]. While the non-cellular components include extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins and many physical and chemical parameters, cellular components of HNSCC TME includes immune cells such as T cells, B cells, natural killer cells (NK cells), langerhans cells, dendritic cells (DC), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), macrophages, tumor associated-platelets (TAPs), mast cells, adipocytes, neuroendocrine cells, blood lymphatic vascular cells, endothelial cells (EC), pericytes and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) [15]. In addition to providing intermediate metabolites and nutrients to the tumor cells, these stromal cells secrete a diverse array of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors that support tumor growth, progression, metastasis [16], host immunosuppression [17], and promote the development of aggressive tumors [18] (Figure 1). However, dysfunctional T-cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs), MDSCs, impaired NK cell activity, and type 2 macrophages (M2) present in the HNSCC TME have an inverse function and promote tumor growth, metastasis, and resistance to therapy [19]. The immunosuppressive HNSCC TME is also facilitated by the downregulation of MHC molecules (human leukocyte antigen, HLA), inactivation of the antigen processing machinery (APM), and dysregulation of checkpoint proteins (reviewed in [20]). The important HNSCC-associated TME cells, cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors are discussed below.

Figure 1. Chemokine and cytokine-mediated crosstalk in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) tumor micro-environment (TME). Cytokines and chemokines secreted by a variety of stromal cells affect tumor cell growth, proliferation & metastasis in many ways. By inducing immune-suppressive TME, they promote immune evasion and metastasis. Many chemokines and cytokines help degrade extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, induce angiogenesis, and thereby promote invasion and metastasis.

Cancer-associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) are the major cell type in the HNSCC and help maintain a favorable TME aiding tumorigenesis [21]. Though controversial, CAFs are believed to be generated from myofibroblasts, transformed cancer cells, epithelial cells via epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), resting resident fibroblasts or pericytes via mesothelial-mesenchymal transition (MMT), endothelial cells via endothelial to mesenchymal transition (EndMT), adipocytes, and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [22]. HNSCC CAF’s secrete a wide variety of cytokines (autocrine or paracrine in function) and tumor-promoting factors essential for inflammation, cell proliferation, tumor growth, invasion & metastasis, angiogenesis, cancer stem cell (CSC) maintenance, and resistance to therapy [23]. These include various cytokines, interleukins (ILs) such as IL-6, IL-17A, and IL-22, growth factors such as EGF, HGF, VEGF, chemokines such as C-X-C motif chemokine ligands (CXCLs), CXCL1, CXCL8, CXCL12 (SDF-1α), and CXCL14, and C-C motif chemokine ligands (CCLs), CCL2, CCL5 and CCL7 [24][25]. These factors promote ECM degradation and modulation by secreting matrix metalloproteins (MMPs) such as MMP-2 and MMP-9 for effective invasion and metastasis of tumor cells [26]. Endothelins (iso-peptides) produced by vascular epithelium upon binding to CAFs activate ADAM17 and trigger release of EGFR ligands such as amphiregulin and TGF-α [26]. These ligands activate EGFR signaling in HNSCC cells, upregulate COX-2 and stimulate the growth, invasion, and metastasis of HNSCC cells [27]. Although little is known about the interaction of CAF-tumor cells in HNSCC, poor overall survival (OS) of HNSCC patients has been associated with increased α-SMA expression regardless of the clinical stage [23]. All these findings ascertain the credibility of CAFs in promoting growth and thus can be useful in facilitating the development of new therapeutic strategies against tumor progression in HNSCC.

Macrophages engage in both innate and adaptive immune responses and protect the body against invading pathogens. These macrophages can either help tumor growth or destroy tumor cells depending upon the external cues from TME. In response to interferons, macrophages are polarized and activated into pro-inflammatory classical M1 type that produces cytokines, such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-23, IL-12, CCL5, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL5 and help destroy tumor cells via activating Th1 cells [28]. M2 type macrophages closely resemble tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and are characterized by increased expression of IFN-γ, CCL2, CCL5, CXCL16, CXCL10, CXCL9, TNF-α, MMP9 and IL-10, arginase-1, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) [29]. HNSCC tumors with high M2 TAM infiltration have an advanced stage lymph node metastasis, and poor patient outcome [30]. Elevated CD68+ macrophages are also associated with poor patient survival [31]. Furthermore, increased M2 TAM infiltration is associated with increased tissue levels of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) and serum TGF-β levels. Though TGF-β is suppressive in function, MIF helps recruit neutrophils to the TME and promotes invasion and metastasis by producing ROS, MMP9 and, VEGF expression [32]. All these studies conclusively established the pro-tumorigenic role of M2 TAMs in regulating cell proliferation, invasion & metastasis, angiogenesis, and promoting immune evasion.

Neutrophils are the most abundant granulocytes present in the blood and an important component of innate and adaptive immunity by regulating T cell activation, antigen presentation and T cell-independent antibody responses [33]. Like TAMs, tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) can be either tumor-promoting (N2) or tumor suppressors (N1). By activating platelets, neutrophils enhance the risk of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism (VTE) and death in HNSCC patients [34]. Due to the lack of specific markers, identification and characterization of TANs are difficult. However, nonspecific markers including CD14, CD15, CD16, CD11b, CD62L and CD66b are routinely used for their isolation and characterization (reviewed [30]). Natural Killer (NK) cells are large granular CD3−ve cytotoxic type 1 innate lymphoid cells that detect and kill virus-infected and cancer cells. Based on the expression of adhesion molecules CD56 and the low-affinity FcγR CD16, NK cells are classified into a highly cytotoxic CD56lowCD16high population predominantly present in the peripheral blood, and less cytotoxic CD56highCD16low cells present in the secondary lymphoid and other tissues [35]. These CD56highCD16low NK cells, like neutrophils and macrophages, kill cells directly by secreting a plethora of immunomodulatory molecules such as IL-5, IL-8, IL-10, IL-13, CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5 IFN-γ, TNF-α, GM-SCF and, CXCL10 [36]. Recently, tumor-infiltrating NK cells from HNSCC patients have been shown to possess a decreased expression of activating receptors like NKG2D, DNAM-1, NKp30, CD16, and 2B4 and upregulation of inhibitory receptors NKG2A and PD-1 compared to NK cells from matched peripheral cells [37]. The study also observed low cytotoxicity and reduced IFN-γ secretion from tumor-infiltrating NK cells in vitro [37]. Though no stimulation is needed for NK activation, a small percentage of NK T-cells (NKT) require priming for activation [38]. These NKT cells are specialized cells with morphological and functional characteristics and surface markers of both T and NK cells. The presence of another small subset of invariant NK T cells (iNKT) that express invariant αβ T cell receptors is associated with poor outcomes for HNSCC patients [39][40].

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are another class of inhibitory immune cells present in the TME of almost all solid tumors. MDSCs are a heterogeneous population of immature immune cells comprising early myeloid progenitors, immature dendritic cells (DCs), neutrophils, and monocytes, which negatively regulate the activity of NK cells and induce Tregs [41]. Though difficult to identify due to their diversity, MDSCs were initially identified from HNSCC patients as immature CD34+ cells [42][43]. MDSCs inhibit the production of innate inflammatory cytokines such as IL-23, IL-12, and IL-1 by DCs, thereby suppressing antitumor IFN-γ secreting CD4+ and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells [44]. They regulate T cell activation, migration, proliferation and induce apoptosis by overexpressing immunomodulatory cytokines like IL-10, TGF-β, CD86, PD-L1, TGF-β and suppressing IFN-γ production [45]. MDSCs indirectly suppress the T- cell activation by inducing Tregs, TAMs, and modulating NK cell activity. They also promote angiogenesis and metastasis by producing βFGF, TGF-β and, VEGFA and degrading ECM [46]. Therefore, targeting the inhibitory functions of MDSCs represents a novel avenue for therapeutic intervention in HNSCC tumors.

Regulatory T-cells are immunosuppressive cells with a crucial function in maintaining self-tolerance immune homeostasis (reviewed in [44]). They are also known to regulate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, macrophages, B cells, NK cells, and DCs. Based on origin, localization, and marker expression, Tregs are mainly divided into CD25+ CD4+ Tregs (natural regulatory T cells) that mature in the thymus and peripheral CD25+ CD4+ Tregs (induced or adaptive Tregs). [47]. These Tregs are known to function by releasing IL-35, IL-10, and TGF-β, inhibiting DC maturation, cytolysis and granzyme/perforin dependent killing of cells, metabolic disruption of effector T cells, and modulation of DC maturation [48]. The genomic and epigenomic differences between HPV+ve and HPV−ve HNSCC tumors favor less infiltration of PD-1 and TIM3 co-expressing CD8+ T-cells in HPV−ve HNSCC [49]. On the contrary, HPV+ve HNSCC tumors are infiltrated with increased Tregs, Tregs/CD8+, and CD56low NK cells, CD56+ CD3+ NKT cells, CD3+ T cell, and activated T cells with increased CTLA4 and PD-1 expression and PD-1/TIM3 co-expressing CD8+ T cells, suggesting compromised immune system [50]. All these studies suggest heterogeneity in cellular phenotype, function, and location among HPV+ve and HPV−ve HNSCC tumors and may potentially be responsible for the varied therapeutic responses.

Besides Tregs, MDSCs, NK, macrophages, neutrophils, platelets, mast cells, adipose cells, and neuroendocrine cells constitute an integral part of the HNSCC TME. In addition to their thrombosis and wound healing activities, thrombocytes or platelets play an important role in tumor biology and inflammation. Besides the secretion of specific granules, viz. dense granules, lysosomes, and α-granules involved in platelet aggregation, platelets also secrete various growth factors in the TME [51]. Interestingly, these granules also contain membranous protein CD63 and lysosomal associated membrane protein 1 & 2 (LAMP1/2), integrin α2β3, p-selectin and glycoprotein-Iβ (GP-Iβ), and secrete molecules like ATP, ADP, Ca2+, serotonin, phosphatase into the TME [52]. It is interesting to mention that CD63 and LAMP1/2 membrane proteins help create an acidic environment for acid hydrolases’ optimum activity to degrade ECM [53]. Besides, α-granules also contain many growth factors, a wide variety of chemokines, MMPs, proteins like thrombospondin, fibrinogen, fibronectin, vitronectin, Von Willebrand factor (VWF), and inflammatory proteins that stimulate tumor growth and angiogenesis [54].

Mast cells are another critical component of the immune system regulating both innate and acquired immune response. When mast cells undergo cross-linkage with IgE receptor (FcERI) on their surface, mast cells exocytose many inflammatory mediators including histamine, heparin, prostaglandin D2 (PGD2), leukotriene C4 (LTC4), chondroitin sulfate E, chymase, tryptase, Cathepsin G, carboxypeptidase-A (CPA1), GM-CSF and interleukins into the TME [55]. These cells also secrete fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), VEGF, MMPs, protease, cytokines, chemokines, and promote proliferation, invasion, and migration of neoplastic cells and angiogenesis [56][57]. Mast cells produce numerous pro-angiogenic factors specific to HNSCC TME, such as FGFβ, TGFβ, tryptase, heparin, and MMPs, to support growth and development [58].In the HNSCC, increased mast cell numbers have been associated with angiogenesis and tumor progression [59].

Neuroendocrine cells release norepinephrine (NE) and epinephrine (E) neurotransmitters. They may either show strong antitumor properties or pro-tumorigenic effects by regulating tumor cell invasion and migration and modulating the immune response. Neurotransmitter substance P (SP) (a member of the tachykinin neuropeptide family), secreted by both tumor and stromal cells, is known to induce many cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α). Neurotransmitter SP stimulates tumor cell migration and blocks the integrin β1 mediated adhesion of T cells [60]. In addition, SP also acts as a mitogen factor via a neurokinin-1 receptor (NK-1R), activates protein kinases (PK1 and 2), and promotes cell migration [61], proliferation and protection from apoptosis [62]. Interestingly, both SP and NK-1R are overexpressed and associated with the development and progression of HNSCC [63][64]. Secretion of NE neurotransmitters also inhibits TNF-α synthesis and thereby prevents the generation of CTLs [65]. The α- and β-adrenoreceptors (ARs) for NE and E are overexpressed in the HNSCC cell lines [66], and administration of NE has been shown to increase the proliferation of these cells [67]. A recent study has shown that increased expression of β2-AR promotes EMT in HNSCC cells by activating the IL-6/STAT3/Snail1 signaling pathway [68]. In addition, increased expression of β2-AR was associated with differentiation, lymph node metastasis, and reduced OS of HNSCC patients [68].

Dendritic cells are the most potent antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Through their interaction with lymphoid and myeloid cells, DCs play a vital role in regulating adaptive and innate immune responses during normal and pathophysiological conditions [69]. DCs become immunogenic upon maturation by up-regulation of MHC class II, co-stimulatory molecules, and by secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-12, TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 [70]. Interestingly, tumor-associated or tumor-treated DCs show low levels of co-stimulatory molecules [71], slow production of IL-12, inhibited antigen-processing machinery (APM), suppressed endocytic activity, and abnormal motility, etc. [72][73]. While higher tumor infiltration of immature DCs is usually observed, increased immature DCs in patients’ peripheral blood with HNSCC, esophageal, lung, and breast cancer have also been reported [74]. Through abortive proliferation, anergy of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes or Tregs produce IL-10 and TGF-β and prevent immune response, immature DCs also induce tolerance, thus inhibiting co-stimulatory signals [75][76].

Endothelial cells (ECs) play an important role in the development and progression of many tumors [77]. By secreting large amounts of VEGF [78], ECs, in an autocrine manner, induce Bcl-2 expression in the TME micro-vessels and promote angiogenesis and tumor growth [79][80][81]. By regulating the secretion of various CXC chemokines in the HNSCC TME, Bcl-2 is known to enhance invasiveness and the development of recurrent tumors [82][83]. VEGF via IKK/IκB/NF-κB signaling pathway also modulates the expression levels of growth-related oncogene GRO-α (or CXCL1) and interleukin 8 (CXCL8) expression in HNSCC [79] and promotes the development of aggressive tumors. Another study reported that Jagged1, a notch ligand, induced by the growth factors via the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase-activator protein-1 (MAPK) in HNSCC cells, triggered Notch signaling in adjacent endothelial cells, thus enhancing neovascularization and tumor growth in vivo [84]. Like the ECs, pericytes are an important cellular component of TME and critically important for tumor initiation, progression, and angiogenesis [85]. Pericytes and ECs communicate with each other by paracrine signaling or by chemo-mechanical signaling pathways [86]. By providing mechanical and physiological support to EC, pericytes stabilize vascular walls, promote vessel remodeling, maturation [87][88], regulation of blood flow, and vessel permeability [89]. Although, there are limited studies on the role of pericytes in HNSCC, some studies have shown the presence of abnormal vessels in the OSCC tumor tissue and a reduction of pericyte population in the peritumoral area, thus showing that the pericyte population is significantly affected during OSCC development [90][91][92].

Extracellular Matrix and Chemokine/Cytokine Activation

The ECM is a 3D network of interwoven macromolecules including glycoproteins, structural fibrous proteins (collagen, elastin, fibronectin, laminin, and tenascin), immersed with enzymes, growth factors, non-cellular components, physical and chemical parameters such as pH, oxygen tension, interstitial pressure, and fluid flux. The ECM provides biophysical, structural, mechanical, and biochemical support to the surrounding cells and helps in-cell adhesion, cell–cell communication, and differentiation [93][94]. Collagen, which constitutes about 30–40% of the total mass of ECM, plays a vital role in cell behavior regulation and development by providing mechanical and structural support and helps in cell adhesion, differentiation, migration, wound repair, and tissue scaffoldings [95][96]. Overexpression of type IV collagen is often observed in HNSCC [97], and collagen XVII, Col15 interaction with integrins has been shown to chemotactically attract HNSCC cells [98]. Notably, Type I collagen has been shown to stimulate the expression of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and TGF-β in HNSCC [99]. Glycoprotein fibronectin (Fn) produced by fibroblasts and endothelial cells interacts with fibrin, integrins, heparin, collagen, gelatin, and syndecan and promotes tumor progression, migration, invasion, and therapeutic resistance [100]. Peptide hydrolases and MMPs produced by tumor and stromal cells cleave the basement membrane, cell surface receptors, and adhesion molecules and result in the disorganization and deregulation of ECM necessary for invasion and metastasis [101][102]. As in many tumors, ECM proteins such as collagen, laminin, and fibronectin have been shown to promote HNSCC tumor growth, progression, and metastasis [103][104]. Besides, increased expression of fibronectin, tenascin, and decreased expression of laminin, collagen type IV and vitronectin have also been reported to be associated with aggressive HNSCC phenotypes [30][105][106][107]. While the interaction of integrins, particularly α5β1 integrin with fibronectin, and αvβ5 with vitronectin were shown to modulate HNSCC cell behavior, αvβ3-osteopontin, αvβ3-fibronectin, and α5β1-fibronectin interactions are involved in angiogenesis [108]. Overall, ECM plays a very pivotal role in the development and metastasis of tumors by altering the phenotype of stromal or tumor cells, availability of secreted cytokines/chemokines and growth factors, providing acidic and hypoxic conditions for the tumor cells to survive and prevent neoplastic cells from immune attack [109].

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424.

- Leemans, C.R.; Braakhuis, B.J.; Brakenhoff, R.H. The molecular biology of head and neck cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 9–22.

- Blot, W.J.; McLaughlin, J.K.; Winn, D.M.; Austin, D.F.; Greenberg, R.S.; Preston-Martin, S.; Bernstein, L.; Schoenberg, J.B.; Stemhagen, A.; Fraumeni, J.F., Jr. Smoking and drinking in relation to oral and pharyngeal cancer. Cancer Res. 1988, 48, 3282–3287.

- Turner, M.D.; Nedjai, B.; Hurst, T.; Pennington, D.J. Cytokines and chemokines: At the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1843, 2563–2582.

- Commins, S.P.; Borish, L.; Steinke, J.W. Immunologic messenger molecules: Cytokines, interferons, and chemokines. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 125 (Suppl. 2), S53–S72.

- Hromas, R.; Broxmeyer, H.E.; Kim, C.; Nakshatri, H.; Christopherson, K., 2nd; Azam, M.; Hou, Y.H. Cloning of BRAK, a novel divergent CXC chemokine preferentially expressed in normal versus malignant cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 255, 703–706.

- Bacon, K.; Baggiolini, M.; Broxmeyer, H.; Horuk, R.; Lindley, I.; Mantovani, A.; Maysushima, K.; Murphy, P.; Nomiyama, H.; Oppenheim, J.; et al. Chemokine/chemokine receptor nomenclature. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. Off. J. Int. Soc. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002, 22, 1067–1068.

- Cameron, M.J.; Kelvin, D.J. Cytokines and chemokines--their receptors and their genes: An overview. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2003, 520, 8–32.

- Strieter, R.M.; Burdick, M.D.; Mestas, J.; Gomperts, B.; Keane, M.P.; Belperio, J.A. Cancer CXC chemokine networks and tumour angiogenesis. Eur. J. Cancer 2006, 42, 768–778.

- Luster, A.D. Chemokines—Chemotactic cytokines that mediate inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 436–445.

- Belperio, J.A.; Keane, M.P.; Arenberg, D.A.; Addison, C.L.; Ehlert, J.E.; Burdick, M.D.; Strieter, R.M. CXC chemokines in angiogenesis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2000, 68, 1–8.

- Borish, L.C.; Steinke, J.W. 2. Cytokines and chemokines. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 111 (Suppl. 2), S460–S475.

- Akdis, M.; Burgler, S.; Crameri, R.; Eiwegger, T.; Fujita, H.; Gomez, E.; Klunker, S.; Meyer, N.; O’Mahony, L.; Palomares, O.; et al. Interleukins, from 1 to 37, and interferon-γ: Receptors, functions, and roles in diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 127, 701–721.e70.

- Chen, F.; Zhuang, X.; Lin, L.; Yu, P.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Hu, G.; Sun, Y. New horizons in tumor microenvironment biology: Challenges and opportunities. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 45.

- Bhat, A.A.; Yousuf, P.; Wani, N.A.; Rizwan, A.; Chauhan, S.S.; Siddiqi, M.A.; Bedognetti, D.; El-Rifai, W.; Frenneaux, M.P.; Batra, S.K.; et al. Tumor microenvironment: An evil nexus promoting aggressive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and avenue for targeted therapy. Signal. Transduct Target. 2021, 6, 12.

- Cheng, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Wu, Q.; Donnola, S.; Liu, J.K.; Fang, X.; Sloan, A.E.; Mao, Y.; Lathia, J.D.; et al. Glioblastoma stem cells generate vascular pericytes to support vessel function and tumor growth. Cell 2013, 153, 139–152.

- Quezada, S.A.; Peggs, K.S.; Simpson, T.R.; Allison, J.P. Shifting the equilibrium in cancer immunoediting: From tumor tolerance to eradication. Immunol. Rev. 2011, 241, 104–118.

- Giancotti, F.G. Deregulation of cell signaling in cancer. Febs Lett. 2014, 88, 2558–2570.

- Tlsty, T.D.; Hein, P.W. Know thy neighbor: Stromal cells can contribute oncogenic signals. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2001, 11, 54–59.

- Canning, M.; Guo, G.; Yu, M.; Myint, C.; Groves, M.W.; Byrd, J.K.; Cui, Y. Heterogeneity of the Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Immune Landscape and Its Impact on Immunotherapy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 52.

- Sazeides, C.; Le, A. Metabolic Relationship between Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and Cancer Cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1063, 149–165.

- Xing, F.; Saidou, J.; Watabe, K. Cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in tumor microenvironment. Front. Biosci 2010, 15, 166–179.

- Kalluri, R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 582–598.

- Augsten, M.; Sjöberg, E.; Frings, O.; Vorrink, S.U.; Frijhoff, J.; Olsson, E.; Borg, Å.; Östman, A. Cancer-associated fibroblasts expressing CXCL14 rely upon NOS1-derived nitric oxide signaling for their tumor-supporting properties. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 2999–3010.

- Jia, C.C.; Wang, T.T.; Liu, W.; Fu, B.S.; Hua, X.; Wang, G.Y.; Li, T.J.; Li, X.; Wu, X.Y.; Tai, Y.; et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts from hepatocellular carcinoma promote malignant cell proliferation by HGF secretion. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63243.

- Glentis, A.; Oertle, P.; Mariani, P.; Chikina, A.; El Marjou, F.; Attieh, Y.; Zaccarini, F.; Lae, M.; Loew, D.; Dingli, F.; et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts induce metalloprotease-independent cancer cell invasion of the basement membrane. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 924.

- Hinsley, E.E.; Hunt, S.; Hunter, K.D.; Whawell, S.A.; Lambert, D.W. Endothelin-1 stimulates motility of head and neck squamous carcinoma cells by promoting stromal-epithelial interactions. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 40–47.

- Atri, C.; Guerfali, F.Z.; Laouini, D. Role of Human Macrophage Polarization in Inflammation during Infectious Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2018, 19, 1801.

- Liu, C.Y.; Xu, J.Y.; Shi, X.Y.; Huang, W.; Ruan, T.Y.; Xie, P.; Ding, J.L. M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophages promoted epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer cells, partially through TLR4/IL-10 signaling pathway. Lab. Investig. A J. Tech. Methods Pathol. 2013, 93, 844–854.

- Peltanova, B.; Raudenska, M.; Masarik, M. Effect of tumor microenvironment on pathogenesis of the head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 63.

- Wolf, G.T.; Chepeha, D.B.; Bellile, E.; Nguyen, A.; Thomas, D.; McHugh, J. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) and prognosis in oral cavity squamous carcinoma: A preliminary study. Oral Oncol. 2015, 51, 90–95.

- Galdiero, M.R.; Garlanda, C.; Jaillon, S.; Marone, G.; Mantovani, A. Tumor associated macrophages and neutrophils in tumor progression. J. Cell. Physiol. 2013, 228, 1404–1412.

- Liew, P.X.; Kubes, P. The Neutrophil’s Role During Health and Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1223–1248.

- Paneesha, S.; McManus, A.; Arya, R.; Scriven, N.; Farren, T.; Nokes, T.; Bacon, S.; Nieland, A.; Cooper, D.; Smith, H.; et al. Frequency, demographics and risk (according to tumour type or site) of cancer-associated thrombosis among patients seen at outpatient DVT clinics. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 103, 338–343.

- Stabile, H.; Fionda, C.; Gismondi, A.; Santoni, A. Role of Distinct Natural Killer Cell Subsets in Anticancer Response. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 293.

- Teng, T.S.; Ji, A.L.; Ji, X.Y.; Li, Y.Z. Neutrophils and Immunity: From Bactericidal Action to Being Conquered. J. Immunol. Res. 2017, 2017, 9671604.

- Korrer, M.J.; Kim, Y. Phenotypical and functional analysis of natural killer cells from primary human head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. J. Immunol. 2019, 202 (Suppl. 1), 134.19.

- Chan, C.J.; Smyth, M.J.; Martinet, L. Molecular mechanisms of natural killer cell activation in response to cellular stress. Cell death and differentiation 2014, 21, 5–14.

- Horinaka, A.; Sakurai, D.; Ihara, F.; Makita, Y.; Kunii, N.; Motohashi, S.; Nakayama, T.; Okamoto, Y. Invariant NKT cells are resistant to circulating CD15+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells in patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 207–216.

- Takami, M.; Ihara, F.; Motohashi, S. Clinical Application of iNKT Cell-mediated Anti-tumor Activity Against Lung Cancer and Head and Neck Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2021.

- Youn, J.I.; Nagaraj, S.; Collazo, M.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 5791–5802.

- Garrity, T.; Pandit, R.; Wright, M.A.; Benefield, J.; Keni, S.; Young, M.R. Increased presence of CD34+ cells in the peripheral blood of head and neck cancer patients and their differentiation into dendritic cells. Int. J. Cancer 1997, 73, 663–669.

- Pak, A.S.; Wright, M.A.; Matthews, J.P.; Collins, S.L.; Petruzzelli, G.J.; Young, M.R. Mechanisms of immune suppression in patients with head and neck cancer: Presence of CD34(+) cells which suppress immune functions within cancers that secrete granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 1995, 1, 95–103.

- Butt, A.Q.; Mills, K.H. Immunosuppressive networks and checkpoints controlling antitumor immunity and their blockade in the development of cancer immunotherapeutics and vaccines. Oncogene 2014, 33, 4623–4631.

- Chikamatsu, K.; Sakakura, K.; Toyoda, M.; Takahashi, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Masuyama, K. Immunosuppressive activity of CD14+ HLA-DR- cells in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Sci. 2012, 103, 976–983.

- Du, R.; Lu, K.V.; Petritsch, C.; Liu, P.; Ganss, R.; Passegué, E.; Song, H.; Vandenberg, S.; Johnson, R.S.; Werb, Z.; et al. HIF1alpha induces the recruitment of bone marrow-derived vascular modulatory cells to regulate tumor angiogenesis and invasion. Cancer Cell 2008, 13, 206–220.

- Zheng, S.G.; Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Gray, J.D.; Horwitz, D.A. IL-2 is essential for TGF-beta to convert naive CD4+CD25- cells to CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells and for expansion of these cells. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 2018–2027.

- Vignali, D.A.; Collison, L.W.; Workman, C.J. How regulatory T cells work. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 523–532.

- Hanna, G.J.; Liu, H.; Jones, R.E.; Bacay, A.F.; Lizotte, P.H.; Ivanova, E.V.; Bittinger, M.A.; Cavanaugh, M.E.; Rode, A.J.; Schoenfeld, J.D.; et al. Defining an inflamed tumor immunophenotype in recurrent, metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Oral Oncol. 2017, 67, 61–69.

- Badoual, C.; Hans, S.; Merillon, N.; Van Ryswick, C.; Ravel, P.; Benhamouda, N.; Levionnois, E.; Nizard, M.; Si-Mohamed, A.; Besnier, N.; et al. PD-1-expressing tumor-infiltrating T cells are a favorable prognostic biomarker in HPV-associated head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 128–138.

- Shah, B.H.; Rasheed, H.; Rahman, I.H.; Shariff, A.H.; Khan, F.L.; Rahman, H.B.; Hanif, S.; Saeed, S.A. Molecular mechanisms involved in human platelet aggregation by synergistic interaction of platelet-activating factor and 5-hydroxytryptamine. Exp. Mol. Med. 2001, 33, 226–233.

- Ruiz, F.A.; Lea, C.R.; Oldfield, E.; Docampo, R. Human platelet dense granules contain polyphosphate and are similar to acidocalcisomes of bacteria and unicellular eukaryotes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 44250–44257.

- Metzelaar, M.J.; Wijngaard, P.L.; Peters, P.J.; Sixma, J.J.; Nieuwenhuis, H.K.; Clevers, H.C. CD63 antigen. A novel lysosomal membrane glycoprotein, cloned by a screening procedure for intracellular antigens in eukaryotic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 3239–3245.

- Gleissner, C.A.; von Hundelshausen, P.; Ley, K. Platelet chemokines in vascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 1920–1927.

- Prussin, C.; Metcalfe, D.D. 4. IgE, mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 111 (Suppl. 2), S486–S494.

- Saleem, S.J.; Martin, R.K.; Morales, J.K.; Sturgill, J.L.; Gibb, D.R.; Graham, L.; Bear, H.D.; Manjili, M.H.; Ryan, J.J.; Conrad, D.H. Cutting edge: Mast cells critically augment myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 511–515.

- Stoyanov, E.; Uddin, M.; Mankuta, D.; Dubinett, S.M.; Levi-Schaffer, F. Mast cells and histamine enhance the proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Lung Cancer 2012, 75, 38–44.

- Ciurea, R.; Mărgăritescu, C.; Simionescu, C.; Stepan, A.; Ciurea, M. VEGF and his R1 and R2 receptors expression in mast cells of oral squamous cells carcinomas and their involvement in tumoral angiogenesis. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. Rev. Roum. Morphol. Embryol. 2011, 52, 1227–1232.

- Barth, P.J.; Schenck zu Schweinsberg, T.; Ramaswamy, A.; Moll, R. CD34+ fibrocytes, alpha-smooth muscle antigen-positive myofibroblasts, and CD117 expression in the stroma of invasive squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx. Virchows Arch. Int. J. Pathol. 2004, 444, 231–234.

- Levite, M. Nerve-driven immunity. The direct effects of neurotransmitters on T-cell function. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 917, 307–321.

- Muñoz, M.; González-Ortega, A.; Rosso, M.; Robles-Frias, M.J.; Carranza, A.; Salinas-Martín, M.V.; Coveñas, R. The substance P/neurokinin-1 receptor system in lung cancer: Focus on the antitumor action of neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists. Peptides 2012, 38, 318–325.

- Koon, H.W.; Zhao, D.; Na, X.; Moyer, M.P.; Pothoulakis, C. Metalloproteinases and transforming growth factor-alpha mediate substance P-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and proliferation in human colonocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 45519–45527.

- Brener, S.; González-Moles, M.A.; Tostes, D.; Esteban, F.; Gil-Montoya, J.A.; Ruiz-Avila, I.; Bravo, M.; Muñoz, M. A role for the substance P/NK-1 receptor complex in cell proliferation in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2009, 29, 2323–2329.

- Mehboob, R.; Tanvir, I.; Warraich, R.A.; Perveen, S.; Yasmeen, S.; Ahmad, F.J. Role of neurotransmitter Substance P in progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2015, 211, 203–207.

- Lala, P.K.; Parhar, R.S.; Singh, P. Indomethacin therapy abrogates the prostaglandin-mediated suppression of natural killer activity in tumor-bearing mice and prevents tumor metastasis. Cell. Immunol. 1986, 99, 108–118.

- Bernabé, D.G.; Tamae, A.C.; Biasoli, É.R.; Oliveira, S.H. Stress hormones increase cell proliferation and regulates interleukin-6 secretion in human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Brain Behav. Immunol. 2011, 25, 574–583.

- Shang, Z.J.; Liu, K.; Liang, D.F. Expression of beta2-adrenergic receptor in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Oral Pathol. Am. Acad. Oral Pathol. 2009, 38, 371–376.

- Liu, H.; Wang, C.; Xie, N.; Zhuang, Z.; Liu, X.; Hou, J.; Huang, H. Activation of adrenergic receptor β2 promotes tumor progression and epithelial mesenchymal transition in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 147–154.

- Shurin, M.R. Dendritic cells presenting tumor antigen. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 1996, 43, 158–164.

- Lutz, M.B.; Schuler, G. Immature, semi-mature and fully mature dendritic cells: Which signals induce tolerance or immunity? Trends Immunol. 2002, 23, 445–449.

- Chaux, P.; Moutet, M.; Faivre, J.; Martin, F.; Martin, M. Inflammatory cells infiltrating human colorectal carcinomas express HLA class II but not B7–1 and B7–2 costimulatory molecules of the T-cell activation. Lab. Investig. A J. Tech. Methods Pathol. 1996, 74, 975–983.

- Shurin, M.R.; Shurin, G.V.; Lokshin, A.; Yurkovetsky, Z.R.; Gutkin, D.W.; Chatta, G.; Zhong, H.; Han, B.; Ferris, R.L. Intratumoral cytokines/chemokines/growth factors and tumor infiltrating dendritic cells: Friends or enemies? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006, 25, 333–356.

- Makarenkova, V.P.; Shurin, G.V.; Tourkova, I.L.; Balkir, L.; Pirtskhalaishvili, G.; Perez, L.; Gerein, V.; Siegfried, J.M.; Shurin, M.R. Lung cancer-derived bombesin-like peptides down-regulate the generation and function of human dendritic cells. J. Neuroimmunol. 2003, 145, 55–67.

- Lizée, G.; Radvanyi, L.G.; Overwijk, W.W.; Hwu, P. Improving antitumor immune responses by circumventing immunoregulatory cells and mechanisms. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 4794–4803.

- Mahnke, K.; Schmitt, E.; Bonifaz, L.; Enk, A.H.; Jonuleit, H. Immature, but not inactive: The tolerogenic function of immature dendritic cells. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2002, 80, 477–483.

- Hawiger, D.; Inaba, K.; Dorsett, Y.; Guo, M.; Mahnke, K.; Rivera, M.; Ravetch, J.V.; Steinman, R.M.; Nussenzweig, M.C. Dendritic cells induce peripheral T cell unresponsiveness under steady state conditions in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2001, 194, 769–779.

- Folkman, J. Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Semin. Oncol. 2002, 29 (Suppl. 16), 15–18.

- Eisma, R.J.; Spiro, J.D.; Kreutzer, D.L. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. 1997, 174, 513–517.

- Kaneko, T.; Zhang, Z.; Mantellini, M.G.; Karl, E.; Zeitlin, B.; Verhaegen, M.; Soengas, M.S.; Lingen, M.; Strieter, R.M.; Nunez, G.; et al. Bcl-2 orchestrates a cross-talk between endothelial and tumor cells that promotes tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 9685–9693.

- Nör, J.E.; Christensen, J.; Mooney, D.J.; Polverini, P.J. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-mediated angiogenesis is associated with enhanced endothelial cell survival and induction of Bcl-2 expression. Am. J. Pathol. 1999, 154, 375–384.

- Nör, J.E.; Christensen, J.; Liu, J.; Peters, M.; Mooney, D.J.; Strieter, R.M.; Polverini, P.J. Up-Regulation of Bcl-2 in microvascular endothelial cells enhances intratumoral angiogenesis and accelerates tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 2183–2188.

- Karl, E.; Warner, K.; Zeitlin, B.; Kaneko, T.; Wurtzel, L.; Jin, T.; Chang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.Y.; Strieter, R.M.; et al. Bcl-2 acts in a proangiogenic signaling pathway through nuclear factor-kappaB and CXC chemokines. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 5063–5069.

- Warner, K.A.; Miyazawa, M.; Cordeiro, M.M.; Love, W.J.; Pinsky, M.S.; Neiva, K.G.; Spalding, A.C.; Nör, J.E. Endothelial cells enhance tumor cell invasion through a crosstalk mediated by CXC chemokine signaling. Neoplasia 2008, 10, 131–139.

- Zeng, Q.; Li, S.; Chepeha, D.B.; Giordano, T.J.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Polverini, P.J.; Nor, J.; Kitajewski, J.; Wang, C.Y. Crosstalk between tumor and endothelial cells promotes tumor angiogenesis by MAPK activation of Notch signaling. Cancer Cell 2005, 8, 13–23.

- Pietras, K.; Ostman, A. Hallmarks of cancer: Interactions with the tumor stroma. Exp. Cell Res. 2010, 316, 1324–1331.

- Durham, J.T.; Surks, H.K.; Dulmovits, B.M.; Herman, I.M. Pericyte contractility controls endothelial cell cycle progression and sprouting: Insights into angiogenic switch mechanics. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2014, 307, C878–C892.

- Ribatti, D.; Nico, B.; Crivellato, E. The role of pericytes in angiogenesis. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2011, 55, 261–268.

- Gerhardt, H.; Betsholtz, C. Endothelial-pericyte interactions in angiogenesis. Cell Tissue Res. 2003, 314, 15–23.

- Bergers, G.; Song, S. The role of pericytes in blood-vessel formation and maintenance. Neuro Oncol. 2005, 7, 452–464.

- Mărgăritescu, C.; Simionescu, C.; Pirici, D.; Mogoantă, L.; Ciurea, R.; Stepan, A. Immunohistochemical characterization of tumoral vessels in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. Rev. Roum. Morphol. Embryol. 2008, 49, 447–458.

- Valle, I.B.; Schuch, L.F.; da Silva, J.M.; Gala-García, A.; Diniz, I.M.A.; Birbrair, A.; Abreu, L.G.; Silva, T.A. Pericyte in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Head Neck Pathol. 2020, 14, 1080–1091.

- Hollemann, D.; Yanagida, G.; Rüger, B.M.; Neuchrist, C.; Fischer, M.B. New vessel formation in peritumoral area of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck 2012, 34, 813–820.

- Muncie, J.M.; Weaver, V.M. The Physical and Biochemical Properties of the Extracellular Matrix Regulate Cell Fate. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2018, 130, 1–37.

- Urbanczyk, M.; Layland, S.L.; Schenke-Layland, K. The role of extracellular matrix in biomechanics and its impact on bioengineering of cells and 3D tissues. Matrix Biol. 2020, 85–86, 1–14.

- Zhu, J.; Liang, L.; Jiao, Y.; Liu, L. Enhanced invasion of metastatic cancer cells via extracellular matrix interface. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118058.

- Schminke, B.; Frese, J.; Bode, C.; Goldring, M.B.; Miosge, N. Laminins and Nidogens in the Pericellular Matrix of Chondrocytes: Their Role in Osteoarthritis and Chondrogenic Differentiation. Am. J. Pathol. 2016, 186, 410–418.

- Cao, X.L.; Xu, R.J.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Liu, J.; Teng, Y.S.; Li, Y.; Zhu, J. Expression of type IV collagen, metalloproteinase-2, metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 in laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2011, 12, 3245–3249.

- Parikka, M.; Nissinen, L.; Kainulainen, T.; Bruckner-Tuderman, L.; Salo, T.; Heino, J.; Tasanen, K. Collagen XVII promotes integrin-mediated squamous cell carcinoma transmigration--a novel role for alphaIIb integrin and tirofiban. Exp. Cell Res. 2006, 312, 1431–1438.

- Koontongkaew, S.; Amornphimoltham, P.; Yapong, B. Tumor-stroma interactions influence cytokine expression and matrix metalloproteinase activities in paired primary and metastatic head and neck cancer cells. Cell Biol. Int. 2009, 33, 165–173.

- Nam, J.M.; Onodera, Y.; Bissell, M.J.; Park, C.C. Breast cancer cells in three-dimensional culture display an enhanced radioresponse after coordinate targeting of integrin alpha5beta1 and fibronectin. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 5238–5248.

- Levental, K.R.; Yu, H.; Kass, L.; Lakins, J.N.; Egeblad, M.; Erler, J.T.; Fong, S.F.; Csiszar, K.; Giaccia, A.; Weninger, W.; et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell 2009, 139, 891–906.

- Provenzano, P.P.; Eliceiri, K.W.; Campbell, J.M.; Inman, D.R.; White, J.G.; Keely, P.J. Collagen reorganization at the tumor-stromal interface facilitates local invasion. BMC Med. 2006, 4, 38.

- Ziober, A.F.; Falls, E.M.; Ziober, B.L. The extracellular matrix in oral squamous cell carcinoma: Friend or foe? Head Neck 2006, 28, 740–749.

- Harada, T.; Shinohara, M.; Nakamura, S.; Oka, M. An immunohistochemical study of the extracellular matrix in oral squamous cell carcinoma and its association with invasive and metastatic potential. Virchows Arch. Int. J. Pathol. 1994, 424, 257–266.

- Agarwal, P.; Ballabh, R. Expression of type IV collagen in different histological grades of oral squamous cell carcinoma: An immunohistochemical study. J. Cancer Res. 2013, 9, 272–275.

- Shruthy, R.; Sharada, P.; Swaminathan, U.; Nagamalini, B. Immunohistochemical expression of basement membrane laminin in histological grades of oral squamous cell carcinoma: A semiquantitative analysis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2013, 17, 185–189.

- Firth, N.A.; Reade, P.C. The prognosis of oral mucosal squamous cell carcinomas: A comparison of clinical and histopathological grading and of laminin and type IV collagen staining. Aust Dent. J. 1996, 41, 83–86.

- Fabricius, E.M.; Wildner, G.P.; Kruse-Boitschenko, U.; Hoffmeister, B.; Goodman, S.L.; Raguse, J.D. Immunohistochemical analysis of integrins alphavbeta3, alphavbeta5 and alpha5beta1, and their ligands, fibrinogen, fibronectin, osteopontin and vitronectin, in frozen sections of human oral head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Exp. Ther. Med. 2011, 2, 9–19.

- Popovic, Z.V.; Sandhoff, R.; Sijmonsma, T.P.; Kaden, S.; Jennemann, R.; Kiss, E.; Tone, E.; Autschbach, F.; Platt, N.; Malle, E.; et al. Sulfated glycosphingolipid as mediator of phagocytosis: SM4s enhances apoptotic cell clearance and modulates macrophage activity. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 6770–6782.