| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Md. Razib Hossain Hossain | + 3203 word(s) | 3203 | 2021-04-25 12:55:04 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 3203 | 2021-05-07 05:12:19 | | | | |

| 3 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 3203 | 2021-05-07 05:13:09 | | |

Video Upload Options

Skin is the largest and most complex organ in the human body comprised of multiple layers with different types of cells. Different kinds of environmental stressors, for example, ultraviolet radiation (UVR), temperature, air pollutants, smoking, and diet, accelerate skin aging by stimulating inflammatory molecules. Skin aging caused by UVR is characterized by loss of elasticity, fine lines, wrinkles, reduced epidermal and dermal components, increased epidermal permeability, delayed wound healing, and approximately 90% of skin aging. These external factors can cause aging through reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated inflammation, as well as aged skin is a source of circulatory inflammatory molecules which accelerate skin aging and cause aging-related diseases.

1. Ultraviolet Radiation (UVR) and Skin Aging

Human skin is the largest organ in the body and protects our internal organs from the external world and is thus exposed to different types of hazardous environmental stimuli. Skin aging is one of the most visible signs of human aging dependent on chronological phenomena (intrinsic aging) and external factors (extrinsic aging or photoaging). Intrinsic aging is a normal physiological process characterized by decreased cell proliferation in basal layers and accumulation of senescent cells in epidermis and dermis resulting in skin dryness, thinning, fine wrinkles, itching [1], and susceptibility to many skin disorders, such as infections, autoimmune disorders, and malignancy [2]. External factors, including pollutants, smoking, diet, temperature, and especially ultraviolet and infrared radiation have larger influence on aggravation of inflammation and aging phenotypes such as wrinkles, irregular pigmentation, skin dryness, and decreased dermal and epidermal thickness [3].

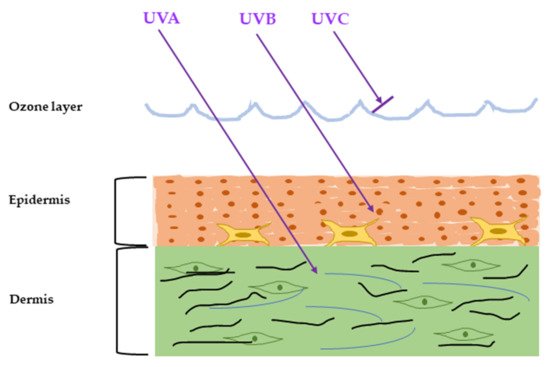

The ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is emitted naturally from the sun and artificial sources and can cause severe damage to the skin, referred to as sun burn. The major artificial sources of UVR are mercury vapor lamps, water-cooled lamps, and air-cooled lamps mainly used for diagnosis and treatment purposes. Chronic exposure to UVR with less dosage causes sun-tan and accelerates skin aging, called photoaging. UVR from sunlight can be classified into three types by their wavelength: UVA (320–400 nm), UVB (280–320 nm), and UVC (100–280 nm) [4]. Among them, almost all UVC and some UVB are absorbed by the ozone layer and do not have any impact on our skin [5][6]. The rest of the UVB can penetrate the skin epidermis and cause erythema (sunburn), while UVA can invade the dermis and is about 98% responsible for major skin aging [7] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Penetration of the solar ultraviolet radiation (UVR) into the skin. According to the wavelength, the UVR is classified into three categories: UVA, UVB, and UVC. UVC is blocked by the ozone layer, UVB can penetrate into the epidermis, and UVA can penetrate up to the dermis.

UVB absorbed by the epidermal cells causes DNA damage, increases oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and leads to premature aging [8][9]. UVA, on the contrary, has a higher wavelength that can cause indirect DNA damage along with collagen and elastin fiber degradation through oxidative stress pathways [4]. Altogether, chronic exposure to UVR results in an increase in nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase and generates ROS, which elevates inflammation, cytokines, chemokines, and skin aging [10]. Chronic and persistent inflammation caused by UVR can weaken skin defense mechanisms and degrade collagen and elastin fibers, and ultimately lead to premature aging. The purpose of this review is to discuss the inflammatory molecules associated with UVR-mediated skin aging.

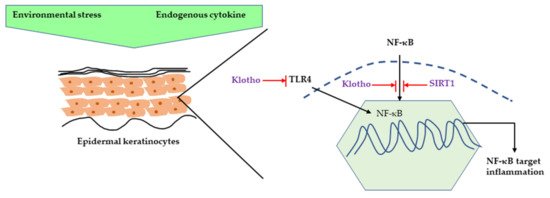

2. Inflammatory Response Caused by UVR

It is well-understood that the acute response of skin to UVR is inflammation, such as erythema and edema, and DNA and mitochondrial damage caused by ROS [11]. The major ROS species involved in this process are superoxide radical anion (O2−), hydroxyl radical (OH), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and singlet oxygen species (O2) [12]. It has been reported that UVB (290–320 nm) exposure caused a significant increase in ROS production in human epidermal keratinocytes (HaCaT) cells along with a decrease in cell viability [13]. ROS is a byproduct of regular oxygen metabolism and is involved in many physiological functions, such as cell signaling, enabling defense mechanisms against pathogens, and cell proliferation. However, UVR exposure to skin can produce increased amounts of ROS, which causes an imbalance between ROS production and antioxidant defense mechanisms, resulting in oxidative stress [10][14]. In a vicious cycle, this oxidative stress can increase ROS production, and can initiate both inflammation and pro-inflammatory cytokine activation, such as interleukin-2 (IL-2), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), involving multiple pathways including nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B (NF-kB), hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1a), nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf-2), and activator protein 1 (AP-1) [15][16]. UVR-related inflammation is also associated with klotho deficiency. Klotho is a transmembrane protein which is also known as an anti-aging hormone protecting against different stressors [17]. Several studies have confirmed that klotho’s function is mediated by the NF-κB pathway. UV irradiation caused a decrease in klotho mRNA and protein expression along with increased pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, such as interleukin-1 β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and TNF-α in HaCaT cells. Moreover, klotho overexpression in human keratinocytes decreased the UV-induced cell damage and inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB nuclear translocation and it also decreased H2O2-induced inflammation by inhibiting Toll-like Receptor 4 expression [18][19]. Sirtuins, a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD(+))-dependent histone deacetylase, is also gaining attention for its ability to increase lifespan as it can delay cellular senescence and promote DNA damage repair. It has been shown that SIRT1, a member of the Sirtuins family, displays an anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting NF-κB signaling. UVR can also cause chronic inflammation by downregulating SIRT1 expression in human keratinocytes [20][21] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Inhibition of NF-κB-induced inflammation by klotho and SIRT1. NF-κB can be activated by different environmental stimuli as well as endogenous cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1. Klotho can inhibit the NF-κB pathway by preventing translocation of NF-κB or inhibiting TLR4-mediated NF-κB activation. SIRT1 prevents the NF-κB pathway by directly inhibiting NF-κB deacetylating NF-κB subunit. NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B; TNF-α, Tumor necrosis factor; IL-1, Interleukin 1; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4, SIRT1, Sirtuin 1.

2.1. Major Inflammatory Responses in Epidermis upon UV Exposure

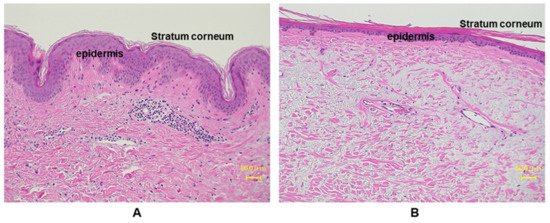

The outermost skin layer is the epidermis, and it is constantly renewing and differentiating. It also works as a barrier against the outer world and is most directly affected by the surrounding environment, mainly UVR. The epidermis mainly consists of four types of cells: predominantly keratinocytes (~90%), melanocytes, Langerhans’ Cells and Merkel Cells [22]. Keratinocytes form a water barrier by means of the stratum corneum (SC), which is generated in the epidermal basal layer, and the tight junctions form a barrier in the stratum granulosum [23]. Almost all UVB is absorbed by the SC, the outermost layer of the epidermis. Several papers have investigated the effects of UVR in epidermis [24][25][26]. The major SC damage caused by UV exposure includes rough and dehydrated texture, reduced desquamation and barrier function, and detrimental effects on cell cohesion [27]. The chronic UV-irradiated epidermis is characterized by thinning of epidermis, fine wrinkles, dryness, and disrupted epidermal barrier function [26][28]. In vitro studies demonstrated an increase in epidermal thickness upon UV irradiation in human samples, whereas in a clinical study, a gradual decrease in epidermal thickness in areas exposed to minimal sunlight has been reported [29][30][31][32]. This discrepancy depends on the chronicity of UV exposure. Acute stimulation with UV enhances keratinocyte proliferation though activating epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), while chronic exposure to sunlight accelerates aging processes, which render epidermis thinner with flattening of rete ridges (Figure 3). On the other hand, non-sun-exposed areas of aged people show comparable thickness to those of young people [33].

Figure 3. Histological comparison between young and aged photo-exposed human skin. Skin specimens from (A) young: 12 years, and (B) aged: 77 years, are stained with hemotoxylin and eosin (HE) staining. Aged human skin epidermis is thinner compared to the young skin, as well as the aged dermis displays increased amounts of degenerated elastic fibers.

It has been demonstrated that UVB exposure disrupted the epidermal barrier function in male hairless Balb/c mice in a dose-dependent manner [34][35], and skin barrier disruption can lead to acute inflammatory response or exacerbation of chronic inflammatory skin diseases, such as atopic dermatitis [36]. Transepidermal water loss (TEWL) is commonly known as a parameter for measuring skin barrier disruption and many reports have confirmed that different UV doses can cause increase of TEWL in murine and human samples [37][38][39][40]. In epidermis, there are several inflammatory signaling pathways connected to different surface receptors, such as the EGFR [41], transforming growth factor receptors (TGFR) [42][43], toll-like receptors (TLRs) [44], IL-1 receptor, and TNF receptor (TNFR) [45][46][47]. The dominant source of cytokines in epidermis is keratinocytes, and major cytokines secreted from keratinocytes upon UVR irradiation are Interleukins (IL-1, IL-3, IL-6, IL-8, IL-33), colony-stimulating factors (GM-CSF, M-CSF, G-CSF), and transforming growth factor α (TGF-α), transforming growth factor β (TGF- β), TNF-α, high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) [48][49][50]. UVR can activate signaling directly by ROS production or indirectly by DNA or mitochondrial damage and then trigger inflammation. Previous studies regarding UVR-mediated inflammation are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Ultraviolet radiation (UVR)-mediated inflammation.

| Study Type | Study Subject | UV Dose | Inflammatory Cytokine | Aging Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-vivo | DBA/2 mice | 180 mJ/cm2 | TNF-α | Increase epidermal thickness, neutrophil infiltration | [47] |

| In-vivo | HR-1 hairless mice | 100 mJ/cm2 | TNF-α, COX-2, iNOS, IL-6, IL-1β | Skin wrinkle formation, increase epidermal thickness, collagen degradation, mast cell infiltration | [51] |

| In-vivo | HR-1 hairless mice | 100 mJ/cm2 | TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β | Skin wrinkle formation, increase epidermal thickness, collagen degradation, trans epidermal water loss (TEWL) of dorsal skin |

[52] |

| In-vivo | Chinese Kun Ming mice | 100–400 mJ/cm2 | IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, COX-2, PGE2, MMP-1, MMP-3 | Coarse wrinkles, erythema, edema, thickening, leathery appearance, epidermal hyperplasia, reduced collagen fibers | [53] |

| In-vivo | SKH-1 hairless mice | 100 mJ/cm2 | TNF-α, MMP-13, IL-1 β, IL-6 | Increase epidermal thickness, collagen degradation | [54] |

| In-vivo | hairless mice (HRS/J) | 0.384 mW/ cm2 | TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β | Increase epidermal thickness, collagen degradation, mast cell infiltration | [55] |

| In-vivo | hairless mice | 312 nm and 790 µW/cm2 intensity | IL-6, IL-12, TNF-α | Skin wrinkle formation, increase epidermal thickness, collagen degradation, collagen and elastic fibers’ (elastin) degradation |

[39] |

| In-vivo | ICR mice | UVA: 20.81 J/cm2, UVB: 0.47 J/cm2 | MMP-1, MMP-3, TNF-α | Thicker scarf-skin, and a disruption of the skin tissue in dermis | [56] |

| In-vitro | HaCaT and HDFs | 200 mJ/cm2 | TNF-α, IL-1β | Increase senescence-associated β -galactosidase activity, increase ROS production | [57] |

| In-vivo | Wister rat | 280–400 nm | IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α | Increase epidermal thickness, disrupted stratum corneum, abnormal hair follicles and loss of histological architecture, uneven sebaceous glands dermis, reduced skin collagen and elastic fibers |

[58] |

| In-vivo and In-vitro | HaCaT | 20 mJ/cm2 | COX-2, MMP-1, FGF, TNF-α, IL-6, and decreased TGF-β1 | Increase ROS production, DNA oxidative damage, reduce procollagen type I | [59] |

| Kunming mice | 150–300 mJ/cm2 | Not investigated | Increase epidermal and dermis thickness, infiltrationof inflammatory cells, decrease collagen fibers |

||

| In-vivo | hairless BALB/c | 55 mJ/cm2 | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 | Increase epidermal and dermis thickness, skin erythema, dry, thickening, sagging, coarse wrinkles, and reduced skin collagen type I |

[60] |

| In-vitro and ex-vivo | NHDFs | 144 mJ/cm2 | TNF-α, IL-6, iNOS, COX-2 | Increase ROS production | [61] |

| Reconstructed human skin (Keraskin™ FT) |

100 mJ/cm2 | Not investigated | Wrinkle formation, disruption and decomposition of collagen fibers in skin tissues exposed to UVB |

||

| In-vivo and In-vitro | HaCaT | 75 mJ/cm2 | TNF-α, IL-6, MMP-1 | Not investigated | [62] |

| hairless mice | 100 mJ/cm2 | MMP-9, MMP-13 | Increase epidermal and dermis thickness | ||

| In-vivo | Human | 25–50 J/ cm2 | IL-6 | Not investigated | [63] |

| In-vivo | hairless mice | 45–210 mJ/cm2 | MMP-2, 9, 12 and 13, TNF-α, IL-1β | Increase epidermal thickness, decrease Type I collagen, deep wrinkle formation | [64] |

| In-vivo | Human | 70 and 90 mJ/cm2 | TNF-α, MMP-1 | Decrease Type I procollagen | [65] |

| In-vivo | Kunming mice | 1 to 4 MED, 1 MED = 70 mJ/cm2 | IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TNF- α, MMP-1, MMP-3 | Reduce skin elasticity, coarse wrinkle formation, erythema, increase epidermal thickness, decrease collagen content | [66] |

| In-vivo and In-vitro | HaCaT cell | 10 mJ/cm2 | IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, MMP-2/9 |

Increase ROS production | [67] |

| BALB/c mice | 180 mJ/cm2 | Not Investigated | Increase epidermal thickness, infiltration of leucocyte | ||

| In-vivo | SKH-1 hairless mice | 30 to 120 mJ/cm2 | MMP-1, 2, 9, COX2, IL-1β, IL-6 | Increase epidermal and dermal thickness, thick and deep wrinkle formation, decrease collagen content | [68] |

| In-vivo and In-vitro | HaCaT cell | 50 J/m2 | COX-2 IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, MMP1, MMP2, MMP9 | Increase cellular senescence | [69] |

| BALB/c athymic nude mice | 60 to 120 mJ/cm2 | COX-2, IL-1β | Increase epidermal thickness, wrinkle formation | ||

| In-vivo | Kunming mice | 1 to 4 MED, 1 MED = 70 mJ/cm2 | IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α | Deep wrinkles, erythema, edema, and skin burn, increase epidermal thickness, degrade dermal collagen fibers, suppress antioxidant enzymes |

[70] |

| In-vivo | Kunming mice | 75 to 300 mJ/cm2 | MMP-1, MMP-3, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1 | Edema, erythema, thickening and coarse wrinkles, epidermal hyperplasia, disorganized collagen fibers |

[71] |

| In-vitro | HaCaT cell | 15 mJ/cm2 | COX-2, TNF-α, IL-1β | Increase ROS production, suppress antioxidant enzymes | [72] |

| In-vivo and In-vitro | HaCaT cell | 12.5 mJ/cm2 | TNF-α, IL-1 α, MMP-1, COX-2 | Not investigated | [73] |

| SKH-1 hairless mice | 36–122 mJ/cm2 | MMP-1 | Increase epidermal and dermal thickness, decrease Type I collagen | ||

| In-vivo | KM mice | 1–4 MED, 1 MED = 100 mJ/cm2 | IL-10, IL-6, TNF-α, MMP-1, MMP-3 | Severe wrinkles, increase epidermal thickness, decease antioxidant enzymes | [74] |

| In-vivo and In-vitro | NHDFs | 90 mJ/cm2 | MMP-1, IL-1 α, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α | Increase ROS production | [75] |

| BALB/c mice | 90 mJ/cm2 | IL-8 | Wrinkle formation, epidermal hyperplasia | ||

| In-vivo | SKH-1 hairless mice | 100–200 mJ/cm2 | MMP-1, MMP-9, decreased TGF-β1 | Increase epidermal thickness, reduce procollagen type I | [76] |

| In-vivo | SKH-1 hairless mice | 280–320 nm | Reduced klotho | Hyper-thickened epidermis | [18] |

HaCaT, Human epidermal keratinocytes; HDFs, Human dermal fibroblasts; NHDFs, Normal human dermal fibroblasts, HSF2; Human skin fibroblasts; MED, minimal erythemal dose; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-a; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; iNOS, Inducible nitric oxide synthase; IL, Interleukin; PGE2, Prostaglandin E2; MMP, Matrix metalloproteinase; FGF, Fibroblast growth factors; TGF-β1, Transforming growth factor beta 1; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

EGFR signaling plays an important role in keratinocyte proliferation, differentiation, cell adhesion, migration, and survival. However, the role of EGFR on inflammatory response upon UVR is very complex. One report demonstrated that UV-irradiated mice and keratinocytes treated with EGFR inhibitor showed suppressed inflammatory responses, such as decreased immune cell infiltration and decreased levels of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-8, IL-1a, Cyclooxygenases (COX2)) [77]. Results also showed that EGFR is partially responsible for p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-activated inflammatory response [77]. It is well-known that p38 MAPK signaling is involved in varied pro-inflammatory cytokine production, leading to various skin pathogenesis, including photoaging. UV-induced COX-2 expression is mostly dependent on the p38 MAPK signaling pathway [78] and regulates prostaglandin 2 (PGE2) secretion, which are major pro-inflammatory cytokines responsible for immune cell infiltration, swelling, and edema [79]. However, some recent reports have shown that prolonged EGFR inhibitor treatment can lead to premature skin aging phenotypes by ROS-induced oxidative stress, or cellular senescence induced by cell cycle arrest [80]. Therefore, the role of EGFR on UVR-mediated skin aging is very complex and yet to be elucidated.

NF-κB is one of the major mediators of cellular inflammatory processes and it is well-established that UV irradiation can increase NF-κB transcriptional activity, resulting in chronic inflammatory signal [81]. Human keratinocytes irradiated with UV showed increased expression of inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α through the NF-κB pathway [82][83]. TLRs are expressed in epidermal keratinocytes and Langerhans cells and are crucial in pathogen identification and immune responses. It has been demonstrated TLRs have important function in UV-mediated inflammation through its downstream signaling pathway involving NF-κB. Specifically, UV-damaged keratinocytes secrete noncoding RNA that can activate TLR3 and induce inflammatory responses, such as TNF-α and IL-6 [84]. Skin epidermis has predominant expression of TNFR, and TNF-α can activate various inflammatory pathways through NF-κB and MAPK. It has been reported that UV irradiation significantly increased both soluble and full-length TNF-α in epidermal keratinocytes [85]. Although epidermis is constantly renewing and cell apoptosis is an essential factor for the epidermis homeostasis, it is also important to note that impaired, premature, or excessive apoptosis can lead to epidermal homeostasis dysregulation and promote aging phenotypes, such as sunburn cells. It has been proven that TNF-α can cause keratinocyte apoptosis by the UV-induced TNFR-1 or p55 receptor pathway [86][87].

The expression of TGF- β is comparatively lower in human epidermis, which is mostly expressed in epidermal basal layers and responsible for epithelial homeostasis, wound healing, and anti-inflammatory response [88]. Chronic UV irradiation can decrease the TGF-β 2 synthesis by reducing TGF-β type II receptor (TβRII) mRNA expression [89][90].

2.2. Major Inflammatory Responses in Dermis upon UV Exposure

The dermis is mainly composed of collagen, elastic fibers, nerves, blood vessels, hair follicles, and glands, where the major component of dermis is collagen [91]. The major cell types in dermis are fibroblasts, vascular smooth muscle cell, macrophages, adipocytes, mast cells, schwann cells, and follicular stem cells [91][92]. Fibroblasts provide dermis with collagen-rich extracellular matrix (ECM) and immune cell infiltration is maintained by blood vessels and lymphatic vessels [93][94]. Photoaged dermis is mostly characterized by thin dermis, decreased collagen content, disorganized and fragmented collagen fibers, elastic fiber degradation, and severe dermal connective tissue damage, which results in most visible signs of skin aging, such as wrinkle formation, fragile atrophic skin, delayed wound healing, and sagging [95]. There are many in-vivo and in-vitro studies that have explored the effects of UVR on dermis (Table 1).

Damaged collagen fibrils and elastin fibers are the most evident component of UVR-mediated aged dermis, mainly caused by the matrix-degrading metalloproteinases (MMPs) synthesis through MAP kinase signaling [14]. MMPs are a family of ubiquitous endopeptidases and participate in inflammatory processes by regulating chemokine activity [96][97]. It has been reported that MMPs are responsible for collagen degradation, mainly through collagenase-1 (MMP-1), stromelysin-1 (MMP-3), and gelatinase B (MMP-9), which directly and fully degrade collagen [98]. One report demonstrated increased expression of MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9, MMP-11, MMP-17, and MMP-27 in a photoaged human forearm correlated with reduced type I procollagen expression [99]. Type I collagen is the most abundant protein in the ECM, and collagen fibrils are synthesized by the procollagens (collagen precursor molecules) through a series of reactions [100]. Another report showed that MMP-1 expression was increased in human UV-irradiated skin along with collagen degradation [101].

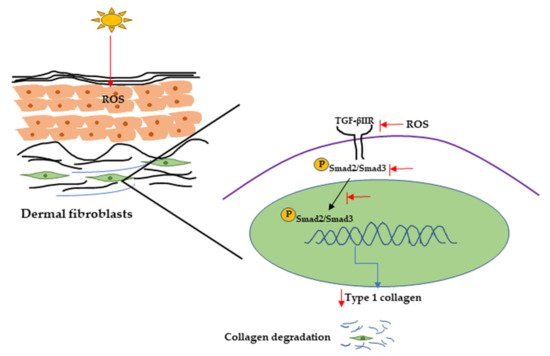

UVR can also initiate collagen degradation by reducing procollagen synthesis, and it has been reported that UVR can reduce procollagen synthesis by downregulating the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway [102]. TGF-β initiates signaling through binding with cell surface receptors (TGF-β type I and type II receptors), then transcription of TGF-β-associated genes by phosphorylating Smad2/Smad3 complex. It has been reported that TGF-β can activate promoter activity of Type I collagen gene (COL1A2) through the Smad signaling pathway [103]. One report showed that UV irradiation inhibits the Smad2/Smad3 nuclear translocation, resulting in decreased TGF-β type II receptor transcription and protein synthesis and procollagen type I expression in hairless mice and in human dermal fibroblasts [76][102][104] (Figure 4).

Figure 4. UVR-induced collagen degradation through the TGF-β pathway. UV radiation can cause a reduction in TGF-β type 2 receptor expression by producing ROS. It can also inhibit Smad2/Smad3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, resulting in decreasing Type 1 collagen expression and collagen degradation. UV, Ultraviolet; TGF-β, transforming growth factor; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

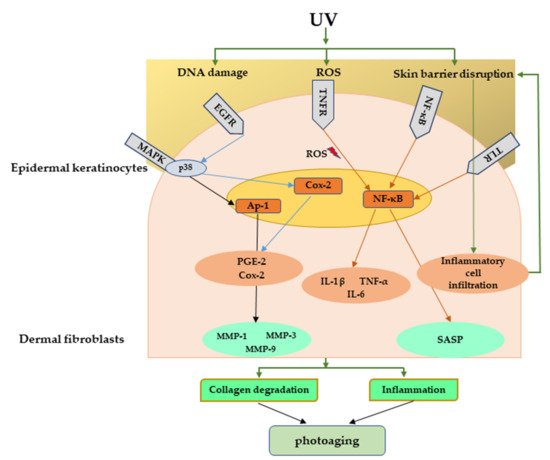

Various stressors including UV radiation can activate DNA damage response that can initiate cell cycle arrest through the p53/p21 pathway involving the P38/MAPK cascade and NF-κB [105] pathway. It has been demonstrated that UV-exposed human skin has significantly high accumulation of senescent cells [106]. Accumulation of senescent fibroblasts can accelerate skin aging by secreting senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors, including IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and MMPs. SASP factors secreted from senescent fibroblasts are responsible for chronic inflammation as well as ECM degradation, resulting in photoaging [107]. Figure 5 explains the major signaling pathways involved in UV-mediated photoaging.

Figure 5. Major signaling pathways involved in UV-mediated photoaging. UV radiation can cause direct damage to the DNA, produce ROS, and disrupt skin barrier function. These can further activate many inflammatory receptors, which can lead to photoaging through inflammation and collagen degradation. UV, Ultraviolet; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

References

- Zhang, S.; Duan, E. Fighting against Skin Aging. Cell Transplant. 2018, 27, 729–738.

- Farage, M.A.; Miller, K.W.; Elsner, P.; Maibach, H.I. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors in skin ageing: A review. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2008, 30, 87–95.

- Tsatsou, F.; Trakatelli, M.; Patsatsi, A.; Kalokasidis, K.; Sotiriadis, D. Extrinsic aging. Dermato-Endocrinology 2012, 4, 285–297.

- Lephart, E.D. Equol’s Anti-Aging Effects Protect against Environmental Assaults by Increasing Skin Antioxidant Defense and ECM Proteins While Decreasing Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 16.

- O’Connor, C.; Courtney, C.; Murphy, M. Shedding light on the myths of ultraviolet radiation in the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 46, 187–188.

- Strzałka, W.; Zgłobicki, P.; Kowalska, E.; Bażant, A.; Dziga, D.; Banaś, A.K. The Dark Side of UV-Induced DNA Lesion Repair. Genes 2020, 11, 1450.

- Mesa-Arango, A.; De Antioquia, U.; Flórez-Muñoz, S.; Sanclemente, G. Mechanisms of skin aging. IATREIA 2017, 30, 160–170.

- Rastogi, R.P.; Richa; Kumar, A.; Tyagi, M.B.; Sinha, R.P. Molecular Mechanisms of Ultraviolet Radiation-Induced DNA Damage and Repair. J. Nucleic Acids 2010, 2010, 1–32.

- Krutmann, J.; Morita, A.; Chung, J.H. Sun Exposure: What Molecular Photodermatology Tells Us About Its Good and Bad Sides. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 976–984.

- Fuller, B. Role of PGE-2 and Other Inflammatory Mediators in Skin Aging and Their Inhibition by Topical Natural Anti-Inflammatories. Cosmetics 2019, 6, 6.

- Mittal, M.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Tran, K.; Reddy, S.P.; Malik, A.B. Reactive Oxygen Species in Inflammation and Tissue Injury. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 1126–1167.

- Yasui, H.; Sakurai, H. Chemiluminescent Detection and Imaging of Reactive Oxygen Species in Live Mouse Skin Exposed to UVA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 269, 131–136.

- Ichihashi, M.; Ueda, M.; Budiyanto, A.; Bito, T.; Oka, M.; Fukunaga, M.; Tsuru, K.; Horikawa, T. UV-induced skin damage. Toxicology 2003, 189, 21–39.

- Kammeyer, A.; Luiten, R. Oxidation events and skin aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 21, 16–29.

- Davinelli, S.; Bertoglio, J.C.; Polimeni, A.; Scapagnini, G. Cytoprotective Polyphenols Against Chronological Skin Aging and Cutaneous Photodamage. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 99–105.

- Imokawa, G. Intracellular Signaling Mechanisms Involved in the Biological Effects of the Xanthophyll Carotenoid Astaxanthin to Prevent the Photo-aging of the Skin in a Reactive Oxygen Species Depletion-independent Manner: The Key Role of Mitogen and Stress-activated Protein Kinase 1. Photochem. Photobiol. 2018, 95, 480–489.

- Hui, H.; Zhai, Y.; Ao, L.; CLeveland, J.C., Jr.; Liu, H.; Fullerton, D.A.; Meng, X. Klotho suppresses the inflammatory responses and ameliorates cardiac dysfunction in aging endotoxemic mice. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 15663–15676.

- Zhang, B.; Xu, J.; Quan, Z.; Qian, M.; Liu, W.; Zheng, W.; Yin, F.; Du, J.; Zhi, Y.; Song, N. Klotho Protein Protects Human Keratinocytes from UVB-Induced Damage Possibly by Reducing Expression and Nuclear Translocation of NF-κB. Med Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 8583–8591.

- Bi, F.; Liu, W.; Wu, Z.; Ji, C.; Chang, C. Antiaging Factor Klotho Retards the Progress of Intervertebral Disc Degeneration through the Toll-Like Receptor 4-NF-κB Pathway. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 2020, 8319516.

- Cao, C.; Lu, S.; Kivlin, R.; Wallin, B.; Card, E.; Bagdasarian, A.; Tamakloe, T.; Wang, W.-J.; Song, X.; Chu, W.-M.; et al. SIRT1 confers protection against UVB- and H2O2-induced cell death via modulation of p53 and JNK in cultured skin keratinocytes. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2008, 13, 3632–3643.

- Lee, D.; Goldberg, A.L. Muscle Wasting in Fasting Requires Activation of NF-κB and Inhibition of AKT/Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) by the Protein Acetylase, GCN5. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 30269–30279.

- Yousef, H.; Alhajj, M.; Sharma, S. Anatomy, Skin (Integument), Epidermis; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020.

- Kubo, A.; Nagao, K.; Amagai, M. Epidermal barrier dysfunction and cutaneous sensitization in atopic diseases. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 440–447.

- Banerjee, S.; Leptin, M. Systemic Response to Ultraviolet Radiation Involves Induction of Leukocytic IL-1β and Inflammation in Zebrafish. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 1408–1415.

- Ansel, J.C.; Luger, T.A.; Green, I. The Effect of In Vitro and In Vivo UV Irradiation on the Production of ETAF Activity by Human and Murine Keratinocytes. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1983, 81, 519–523.

- D’Orazio, J.; Jarrett, S.; Amaro-Ortiz, A.; Scott, T. UV Radiation and the Skin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 12222–12248.

- Biniek, K.; Levi, K.; Dauskardt, R.H. Solar UV radiation reduces the barrier function of human skin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 17111–17116.

- Hwang, I.S.; Kim, J.E.; Choi, S.I.; Lee, H.R.; Lee, Y.J.; Jang, M.J.; Son, H.J.; Lee, H.S.; Oh, C.H.; Kim, B.H.; et al. UV radiation-induced skin aging in hairless mice is effectively prevented by oral intake of sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) fruit blend for 6 weeks through MMP suppression and increase of SOD activity. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2012, 30, 392–400.

- El-Domyati, M.; Attia, S.; Saleh, F.; Brown, D.; Birk, D.E.; Gasparro, F.; Ahmad, H.; Uitto, J. Intrinsic aging vs. photoaging: A comparative histopathological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of skin. Exp. Dermatol. 2002, 11, 398–405.

- Pearse, A.D.; Gaskell, S.A.; Marks, R. Epidermal Changes in Human Skin Following Irradiation With Either UVB or UVA. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1987, 88, 83–87.

- Takema, Y.; Yorimoto, Y.; Kawai, M.; Imokawa, G. Age-related changes in the elastic properties and thickness of human facial skin. Br. J. Dermatol. 1994, 131, 641–648.

- Wan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Voorhees, J.; Fisher, G. EGF receptor crosstalks with cytokine receptors leading to the activation of c-Jun kinase in response to UV irradiation in human keratinocytes. Cell. Signal. 2001, 13, 139–144.

- Giangreco, A.; Goldie, S.J.; Failla, V.; Saintigny, G.; Watt, F.M. Human Skin Aging Is Associated with Reduced Expression of the Stem Cell Markers β1 Integrin and MCSP. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2010, 130, 604–608.

- Jiang, S.J.; Chu, A.W.; Lu, Z.F.; Pan, M.H.; Che, D.F.; Zhou, X.J. Ultraviolet B-induced alterations of the skin barrier and epidermal calcium gradient. Exp. Dermatol. 2007, 16, 985–992.

- Haratake, A.; Uchida, Y.; Schmuth, M.; Tanno, O.; Yasuda, R.; Epstein, J.H.; Elias, P.M.; Holleran, W.M. UVB-Induced Alterations in Permeability Barrier Function: Roles for Epidermal Hyperproliferation and Thymocyte-Mediated Response. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1997, 108, 769–775.

- Kim, B.E.; Leung, D.Y. Significance of Skin Barrier Dysfunction in Atopic Dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2018, 10, 207–215.

- Abe, T.; Mayuzumi, J. The change and recovery of human skin barrier functions after ultraviolet light irradiation. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1979, 27, 458–462.

- Cestone, E.; Michelotti, A.; Zanoletti, V.; Zanardi, A.; Mantegazza, R.; Dossena, M. Acne RA-1,2, a novel UV-selective face cream for patients with acne: Efficacy and tolerability results of a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2017, 16, 265–270.

- Suh, M.G.; Bae, G.Y.; Jo, K.; Kim, J.M.; Hong, K.-B.; Suh, H.J. Photoprotective Effect of Dietary Galacto-Oligosaccharide (GOS) in Hairless Mice via Regulation of the MAPK Signaling Pathway. Molecules 2020, 25, 1679.

- Choi, H.J.; Song, B.R.; Kim, J.E.; Bae, S.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, S.J.; Gong, J.E.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, C.Y.; Kim, B.-H.; et al. Therapeutic Effects of Cold-Pressed Perilla Oil Mainly Consisting of Linolenic acid, Oleic Acid and Linoleic Acid on UV-Induced Photoaging in NHDF Cells and SKH-1 Hairless Mice. Molecules 2020, 25, 989.

- Piepkorn, M.; Predd, H.; Underwood, R.; Cook, P. Proliferation-differentiation relationships in the expression of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-related factors and erbB receptors by normal and psoriatic human keratinocytes. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2003, 295, 93–101.

- Matsuura, H.; Myokai, F.; Arata, J.; Noji, S.; Taniguchi, S. Expression of type II transforming growth factor-β receptor mRNA in human skin, as revealed by in situ hybridization. J. Dermatol. Sci. 1994, 8, 25–32.

- Schmid, P.; Itin, P.; Rufli, T. In situ analysis of transforming growth factors-beta (TGF-beta 1, TGF-beta 2, TGF-beta 3) and TGF-beta type II receptor expression in basal cell carcinomas. Br. J. Dermatol. 1996, 134, 1044–1051.

- Iram, N.; Mildner, M.; Prior, M.; Petzelbauer, P.; Fiala, C.; Hacker, S.; Schöppl, A.; Tschachler, E.; Elbe-Bürger, A. Age-related changes in expression and function of Toll-like receptors in human skin. Dev. 2012, 139, 4210–4219.

- Robert, C.; Kupper, T.S. Inflammatory Skin Diseases, T Cells, and Immune Surveillance. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 1817–1828.

- Kupper, T.S. Immune and inflammatory processes in cutaneous tissues. Mechanisms and speculations. J. Clin. Investig. 1990, 86, 1783–1789.

- Lee, R.T.; Briggs, W.H.; Cheng, G.C.; Rossiter, H.B.; Libby, P.; Kupper, T. Mechanical deformation promotes secretion of IL-1 al-pha and IL-1 receptor antagonist. J. Immunol. 1997, 159, 5084–5088.

- Ansel, J.; Perry, P.; Brown, J.; Damm, D.; Phan, T.; Hart, C.; Luger, T.; Hefeneider, S. Cytokine Modulation of Keratinocyte Cytokines. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1990, 94, s101–s107.

- Johnson, K.E.; Wulff, B.C.; Oberyszyn, T.M.; Wilgus, T.A. Ultraviolet light exposure stimulates HMGB1 release by keratinocytes. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2013, 305, 805–815.

- Meephansan, J.; Komine, M.; Tsuda, H.; Tominaga, S.-I.; Ohtsuki, M. Ultraviolet B irradiation induces the expression of IL-33 mRNA and protein in normal human epidermal keratinocytes. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2012, 65, 72–74.

- Choi, S.; Jung, T.; Cho, B.; Choi, S.; Sim, W.; Han, X.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, Y.; Lee, O. Anti-photoaging effect of fermented agricultural by-products on ultraviolet B-irradiated hairless mouse skin. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 559–568.

- Choi, S.-H.; Choi, S.-I.; Jung, T.-D.; Cho, B.-Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, S.-H.; Yoon, S.-A.; Ham, Y.-M.; Yoon, W.-J.; Cho, J.-H.; et al. Anti-Photoaging Effect of Jeju Putgyul (Unripe Citrus) Extracts on Human Dermal Fibroblasts and Ultraviolet B-induced Hairless Mouse Skin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2052.

- Wang, X.-F.; Huang, Y.-F.; Wang, L.; Xu, L.-Q.; Yu, X.-T.; Liu, Y.-H.; Li, C.-L.; Zhan, J.Y.-X.; Su, Z.-R.; Chen, J.-N.; et al. Photo-protective activity of pogostone against UV-induced skin premature aging in mice. Exp. Gerontol. 2016, 77, 76–86.

- Kwak, C.S.; Yang, J.; Shin, C.-Y.; Chung, J.H. Rosa multiflora Thunb Flower Extract Attenuates Ultraviolet-Induced Photoaging in Skin Cells and Hairless Mice. J. Med. Food 2020, 23, 988–997.

- Martinez, R.M.; Fattori, V.; Saito, P.; Pinto, I.C.; Rodrigues, C.C.A.; Melo, C.P.B.; Bussmann, A.J.C.; Staurengo-Ferrari, L.; Bezerra, J.R.; Vignoli, J.A.; et al. The Lipoxin Receptor/FPR2 Agonist BML-111 Protects Mouse Skin Against Ultraviolet B Radiation. Molecules 2020, 25, 2953.

- Rui, Y.; Zhaohui, Z.; Wenshan, S.; Bafang, L.; Hu, H. Protective effect of MAAs extracted from Porphyra tenera against UV irradiation-induced photoaging in mouse skin. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2019, 192, 26–33.

- Moon, K.-C.; Yang, J.-P.; Lee, J.-S.; Jeong, S.-H.; Dhong, E.-S.; Han, S.-K. Effects of Ultraviolet Irradiation on Cellular Senescence in Keratinocytes Versus Fibroblasts. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2019, 30, 270–275.

- Bora, N.S.; Mazumder, B.; Mandal, S.; Patowary, P.; Goyary, D.; Chattopadhyay, P.; Dwivedi, S.K. Amelioration of UV radiation-induced photoaging by a combinational sunscreen formulation via aversion of oxidative collagen degradation and promotion of TGF-β-Smad-mediated collagen production. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 127, 261–275.

- Qin, D.; Lee, W.-H.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Peng, M.; Sun, T.; Gao, Y. Protective effects of antioxidin-RL from Odorrana livida against ultraviolet B-irradiated skin photoaging. Peptides 2018, 101, 124–134.

- Kong, S.-Z.; Li, D.-D.; Luo, H.; Li, W.-J.; Huang, Y.-M.; Li, J.-C.; Hu, Z.; Huang, N.; Guo, M.-H.; Chen, Y.; et al. Anti-photoaging effects of chitosan oligosaccharide in ultraviolet-irradiated hairless mouse skin. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 103, 27–34.

- Subedi, L.; Lee, T.H.; Wahedi, H.M.; Baek, S.-H.; Kim, S.Y. Resveratrol-Enriched Rice Attenuates UVB-ROS-Induced Skin Aging via Downregulation of Inflammatory Cascades. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 1–15.

- Kang, S.M.; Han, S.; Oh, J.-H.; Lee, Y.M.; Park, C.-H.; Shin, C.-Y.; Lee, D.H.; Chung, J.H. A synthetic peptide blocking TRPV1 activation inhibits UV-induced skin responses. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2017, 88, 126–133.

- Schneider, L.A.; Raizner, K.; Wlaschek, M.; Brenneisen, P.; Gethöffer, K.; Scharffetter-Kochanek, K. UVA-1 exposure in vivo leads to an IL-6 surge within the skin. Exp. Dermatol. 2017, 26, 830–832.

- Misawa, E.; Tanaka, M.; Saito, M.; Nabeshima, K.; Yao, R.; Yamauchi, K.; Abe, F.; Yamamoto, Y.; Furukawa, F. Protective effects ofAloesterols against UVB-induced photoaging in hairless mice. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2017, 33, 101–111.

- Kim, E.J.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, M.-K.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, D.H.; Chung, J.H. UV-induced inhibition of adipokine production in subcutaneous fat aggravates dermal matrix degradation in human skin. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25616.

- Zhan, J.Y.-X.; Wang, X.-F.; Liu, Y.-H.; Zhang, Z.-B.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.-N.; Huang, S.; Zeng, H.-F.; Lai, X.-P. Andrographolide Sodium Bisulfate Prevents UV-Induced Skin Photoaging through Inhibiting Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 1–12.

- Afnan, Q.; Kaiser, P.J.; Rafiq, R.A.; Nazir, L.A.; Bhushan, S.; Bhardwaj, S.C.; Sandhir, R.; Tasduq, S.A. Glycyrrhizic acid prevents ultraviolet-B-induced photodamage: A role for mitogen-activated protein kinases, nuclear factor kappa B and mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Exp. Dermatol. 2016, 25, 440–446.

- Yoo, J.H.; Kim, J.K.; Yang, H.J.; Park, K.M. Effects of Egg Shell Membrane Hydrolysates on UVB-radiation-induced Wrinkle Formation in SKH-1 Hairless Mice. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2015, 35, 58–70.

- Kim, W.; Kim, E.; Yang, H.J.; Kwon, T.; Han, S.; Lee, S.; Youn, H.; Jung, Y.H.; Kang, C.; Youn, B. Inhibition of hedgehog signalling attenuates UVB-induced skin photoageing. Exp. Dermatol. 2015, 24, 611–617.

- Zhang, X.; Xie, Y.-L.; Yu, X.-T.; Su, Z.-Q.; Yuan, J.; Li, Y.-C.; Su, Z.-R.; Zhan, J.Y.-X.; Lai, X.-P. Protective Effect of Super-Critical Carbon Dioxide Fluid Extract from Flowers and Buds of Chrysanthemum indicum Linnén Against Ultraviolet-Induced Photo-Aging in Mice. Rejuvenation Res. 2015, 18, 437–448.

- Kong, S.-Z.; Chen, H.-M.; Yu, X.-T.; Zhang, X.; Feng, X.-X.; Kang, X.-H.; Li, W.-J.; Huang, N.; Luo, H.; Su, Z.-R. The protective effect of 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid against UV irradiation induced photoaging in mice. Exp. Gerontol. 2015, 61, 147–155.

- Kim, M.-J.; Woo, S.W.; Kim, M.-S.; Park, J.-E.; Hwang, J.-K. Anti-photoaging effect of aaptamine in UVB-irradiated human dermal fibroblasts and epidermal keratinocytes. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 16, 1139–1147.

- Oh, J.E.; Kim, M.S.; Jeon, W.-K.; Seo, Y.K.; Kim, B.-C.; Hahn, J.H.; Park, C.S. A nuclear factor kappa B-derived inhibitor tripeptide inhibits UVB-induced photoaging process. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2014, 76, 196–205.

- Feng, X.-X.; Yu, X.-T.; Li, W.-J.; Kong, S.-Z.; Liu, Y.-H.; Zhang, X.; Xian, Y.-F.; Zhang, X.-J.; Su, Z.-R.; Lin, Z.-X. Effects of topical application of patchouli alcohol on the UV-induced skin photoaging in mice. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 63, 113–123.

- Chen, C.-C.; Chiang, A.-N.; Liu, H.-N.; Chang, Y.-T. EGb-761 prevents ultraviolet B-induced photoaging via inactivation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and proinflammatory cytokine expression. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2014, 75, 55–62.

- Chiu, H.-W.; Chen, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-J.; Hsu, Y.-H. Far-infrared suppresses skin photoaging in ultraviolet B-exposed fibroblasts and hairless mice. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174042.

- El-Abaseri, T.B.; Hammiller, B.; Repertinger, S.K.; Hansen, L.A. The Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Increases Cytokine Production and Cutaneous Inflammation in Response to Ultraviolet Irradiation. ISRN Dermatol. 2013, 2013, 1–11.

- Kim, A.L.; Labasi, J.M.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, X.; McClure, K.; Gabel, C.A.; Athar, M.; Bickers, D.R. Role of p38 MAPK in UVB-Induced Inflammatory Responses in the Skin of SKH-1 Hairless Mice. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2005, 124, 1318–1325.

- Murata, K.; Oyama, M.; Ogata, M.; Fujita, N.; Takahashi, R. Oral administration of Jumihaidokuto inhibits UVB-induced skin damage and prostaglandin E2 production in HR-1 hairless mice. J. Nat. Med. 2021, 75, 142–155.

- Gerber, P.A.; Buhren, B.A.; Schrumpf, H.; Hevezi, P.; Bölke, E.; Sohn, D.; Jänicke, R.U.; Belum, V.R.; Robert, C.; Lacouture, M.E.; et al. Mechanisms of skin aging induced by EGFR inhibitors. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 4241–4248.

- O’Dea, E.L.; Kearns, J.D.; Hoffmann, A. UV as an Amplifier Rather Than Inducer of NF-κB Activity. Mol. Cell 2008, 30, 632–641.

- Vicentini, F.T.; He, T.; Shao, Y.; Fonseca, M.J.; Verri, W.A.; Fisher, G.J.; Xu, Y. Quercetin inhibits UV irradiation-induced inflammatory cytokine production in primary human keratinocytes by suppressing NF-κB pathway. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2011, 61, 162–168.

- Xia, J.; Song, X.; Bi, Z.; Chu, W.; Wan, Y. UV-induced NF-kappaB activation and expression of IL-6 is attenuated by (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate in cultured human keratinocytes in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2005, 16, 943–950.

- Bernard, J.J.; Cowing-Zitron, C.; Nakatsuji, T.; Muehleisen, B.; Muto, J.; Borkowski, A.W.; Martinez, L.; Greidinger, E.L.; Yu, B.D.; Gallo, R.L. Ultraviolet radiation damages self noncoding RNA and is detected by TLR3. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1286–1290.

- Jo, J.; Im, S.H.; Babcock, D.T.; Iyer, S.C.; Gunawan, F.; Cox, D.N.; Galko, M.J. Drosophila caspase activity is required independently of apoptosis to produce active TNF/Eiger during nociceptive sensitization. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2786.

- Deshmukh, J.; Pofahl, R.; Haase, I. Epidermal Rac1 regulates the DNA damage response and protects from UV-light-induced keratinocyte apoptosis and skin carcinogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2664.

- Schwarz, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Aragane, Y.; Mahnke, K.; Riemann, H.; Metze, D.; Luger, T.A.; Schwarz, T. Ultraviolet-B-Induced Apoptosis of Keratinocytes: Evidence for Partial Involvement of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α in the Formation of Sunburn Cells. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1995, 104, 922–927.

- Liarte, S.; Bernabé-García, Á.; Nicolás, F.J. Role of TGF-β in Skin Chronic Wounds: A Keratinocyte Perspective. Cells 2020, 9, 306.

- Quan, T.; He, T.; Kang, S.; Voorhees, J.J.; Fisher, G.J. Ultraviolet Irradiation Alters Transforming Growth Factor β/Smad Pathway in Human Skin In Vivo. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2002, 119, 499–506.

- Xu, D.; Yuan, R.; Gu, H.; Liu, T.; Tu, Y.; Yang, Z.; He, L. The effect of ultraviolet radiation on the transforming growth factor beta 1/Smads pathway and p53 in actinic keratosis and normal skin. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2013, 305, 777–786.

- Brown, T.M.; Krishnamurthy, K. Histology, Dermis; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020.

- Prost-Squarcioni, C.; Fraitag, S.; Heller, M.; Boehm, N. Histologie fonctionnelle du derme. Annales de Dermatologie et de Vénéréologie 2008, 135, 5–20.

- Won, H.-R.; Lee, P.; Oh, S.-R.; Kim, Y.-M. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Suppresses the Expression of TNF-α-Induced MMP-1 via MAPK/ERK Signaling Pathways in Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 44, 18–24.

- Mueller, S.N.; Zaid, A.; Carbone, F.R. Tissue-Resident T Cells: Dynamic Players in Skin Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 332.

- Nigam, Y.; Knight, J. Exploring the anatomy and physiology of ageing. Part 11—The skin. Nurs. Times 2009, 104, 24–25.

- Manicone, A.M.; McGuire, J.K. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2008, 19, 34–41.

- Parks, W.C.; Wilson, C.L.; López-Boado, Y.S. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 617–629.

- Shin, J.-W.; Kwon, S.-H.; Choi, J.-Y.; Na, J.-I.; Huh, C.-H.; Choi, H.-R.; Park, K.-C. Molecular Mechanisms of Dermal Aging and Antiaging Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2126.

- Quan, T.; Little, E.; Quan, H.; Qin, Z.; Voorhees, J.J.; Fisher, G.J. Elevated Matrix Metalloproteinases and Collagen Fragmentation in Photodamaged Human Skin: Impact of Altered Extracellular Matrix Microenvironment on Dermal Fibroblast Function. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 1362–1366.

- Kruger, T.E.; Miller, A.H.; Wang, J. Collagen Scaffolds in Bone Sialoprotein-Mediated Bone Regeneration. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 1–6.

- Fisher, G.J.; Choi, H.-C.; Bata-Csorgo, Z.; Shao, Y.; Datta, S.; Wang, Z.-Q.; Kang, S.; Voorhees, J.J. Ultraviolet Irradiation Increases Matrix Metalloproteinase-8 Protein in Human Skin In Vivo. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2001, 117, 219–226.

- Quan, T.; He, T.; Kang, S.; Voorhees, J.J.; Fisher, G.J. Solar Ultraviolet Irradiation Reduces Collagen in Photoaged Human Skin by Blocking Transforming Growth Factor-β Type II Receptor/Smad Signaling. Am. J. Pathol. 2004, 165, 741–751.

- Ghosh, A.K.; Yuan, W.; Mori, Y.; Varga, J. Smad-dependent stimulation of type I collagen gene expression in human skin fibroblasts by TGF-β involves functional cooperation with p300/CBP transcriptional coactivators. Oncogene 2000, 19, 3546–3555.

- Park, B.; Hwang, E.; Seo, S.A.; Zhang, M.; Park, S.-Y.; Yi, T.-H. Dietary Rosa damascena protects against UVB-induced skin aging by improving collagen synthesis via MMPs reduction through alterations of c-Jun and c-Fos and TGF-β1 stimulation mediated smad2/3 and smad7. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 36, 480–489.

- Fridlyanskaya, I.; Alekseenko, L.; Nikolsky, N. Senescence as a general cellular response to stress: A mini-review. Exp. Gerontol. 2015, 72, 124–128.

- Ogata, Y.; Yamada, T.; Hasegawa, S.; Sanada, A.; Iwata, Y.; Arima, M.; Nakata, S.; Sugiura, K.; Akamatsu, H. SASP-induced macrophage dysfunction may contribute to accelerated senescent fibroblast accumulation in the dermis. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 30, 84–91.

- Wlaschek, M.; Maity, P.; Makrantonaki, E.; Scharffetter-Kochanek, K. Connective Tissue and Fibroblast Senescence in Skin Aging. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 985–992.