| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Francisco Gasulla Vidal | + 2080 word(s) | 2080 | 2021-04-29 08:10:05 | | | |

| 2 | Vicky Zhou | Meta information modification | 2080 | 2021-05-05 05:02:58 | | |

Video Upload Options

Lichens are symbiotic associations (holobionts) established between fungi (mycobionts) and certain groups of cyanobacteria or unicellular green algae (photobionts). This symbiotic association has been essential in the colonization of terrestrial dry habitats. Lichens possess key mechanisms involved in desiccation tolerance (DT) that are constitutively present such as high amounts of polyols, LEA proteins, HSPs, a powerful antioxidant system, thylakoidal oligogalactolipids, etc. This strategy allows them to be always ready to survive drastic changes in their water content. However, several studies indicate that at least some protective mechanisms require a minimal time to be induced, such as the induction of the antioxidant system, the activation of non-photochemical quenching including the de-epoxidation of violaxanthin to zeaxanthin, lipid membrane remodeling, changes in the proportions of polyols, ultrastructural changes, marked polysaccharide remodeling of the cell wall, etc. Although DT in lichens is achieved mainly through constitutive mechanisms, the induction of protection mechanisms might allow them to face desiccation stress in a better condition. The proportion and relevance of constitutive and inducible DT mechanisms seem to be related to the ecology at which lichens are adapted to.

1. Introduction

Lichens are stable mutualistic symbioses between a fungus (mycobiont) and at least one photosynthetic partner (photobiont) that can be an eukaryotic algae (phycobiont) and/or a cyanobacteria (cyanobiont). In this association, the mycobiont is the exhabitant that forms a thallus around the photobiont, which provides carbohydrates to the fungus [1]. The oldest cyanobacterial and green algal lichens with heteromerous thallus anatomy (predominance of fungal cells over photobiont cells) so far found, are two fossils from the Lower Devonian (Lochkovian, approx. 415 Myr) [2]. These fossils show the characteristic thallus organization of extant foliose Lecanoromycetes lichens formed by an upper thin and compacted fungal hyphae layer (cortex), a photobiont layer and a lower loosely interwoven hyphae layer (medulla). The morphology and size of the cyanobiont and the phycobiont very strongly resemble extant Nostoc ssp. and Trebouxia ssp., respectively [2]. Recent time-calibration of ascomycete fungi and algal lichen-associated phylogenies show broad congruence and demonstrate that lichen symbiosis appeared during the Devonian period [3]. The origin of embryophytes is estimated in the middle Cambrian-Early Ordovician (∼515.2 Myr to 473.5 Myr) followed by a high diversification in the Silurian period (443.8 Myr to 419.2 Myr) [4]. Thus, lichens emerged in a land already conquered by bryophytes and vascular plants and had to adapt to niches unsuitable for the latter. Extant lichens have a very low growth rate, from millimetres to centimetres per year, and cannot compete directly against land plants for vital sources such as water, light or space.

Lichens occupy habitats with low water retention capacity such as rock surfaces, sand, gypsum soils or tree bark, where land plants cannot survive. This adaptive strategy is mainly based on the tolerance to desiccation. Lichens are poikilohydric organisms, which means they do not have active mechanisms to regulate their water content, and therefore hydration fluctuates with the availability of water in the surrounding environment. When a lichen thallus is hydrated, the photobiont produces carbohydrates through the photosynthetic process-obviously in presence of light-, which are used in its own growth but also to feed the fungus partner. When lichens completely lose their water, they enter anhydrobiosis until the following rehydration. Theoretically, lichens can survive infinite cycles of desiccation/rehydration, the only requisite is to be hydrated -in the light- for enough time to compensate the energetic cost of fungus respiration and to make new carbohydrates for growth. In this sense, besides precipitation, lichens can utilize other water sources, such as fog and dew, and indeed have the ability to extract some moisture from the air, which can help to extend the hydration time. In addition, desiccation confers an extraordinary resistance to extremely high and low temperatures, to insolation and to UV irradiation [5], which allow lichens to conquer stressful environments such as hot deserts and high mountains. The strong similarity between the thallus organization and the photobiont taxonomy of Devonian and extant lichens suggests that early lichens also based their adaption strategy on poikylohydria and DT. This strategy had a great evolutionary success and earliest lichens diversified on land even after the rise and spread of multicellular plants. Nowadays this diverse group is found in almost all terrestrial habitats from the tropics to polar regions and dominate about ~7% of the earth’s terrestrial surface [6].

The scientific study of the specific physiological traits of lichens began in the 19th Century and demonstrated that lichens have the extraordinary capacity to tolerate desiccation for several months [7]. During the following century, lichenologists and other scientists tried to establish the limits and the ecophysiological significance of lichen DT. Probably, the major problem in studies carried out on survival of lichens under extreme conditions is to determine their viability. As we stated above, the growth rate of lichens is very slow, and the effects caused by moderate stress generally cannot be measured within a short period. Thus, “visual investigation of the viability of lichens is unreliable” [8]. Because of these difficulties, many kinds of physiological measurements and observational approaches were used to determine the ability of lichens to survive to extreme environments. One of these methods was to observe whether the symbionts isolated from a stressed lichen thallus grew in culture [9][10]. The measurement of CO2 exchange was also proven to be a reliable indicator for the response of lichens to any environmental influence. Jumelle [11] was the first to study the response of a lichen thallus to stress by using this technique. After him, several authors described different methods of measurement of CO2 exchange in a lichen thallus, reviewed in Kappen et al. [7]. At the end of the 20th Century began the massive use of chlorophyll fluorescence measurements to determine lichen fitness through the analysis of the photobiont photosynthesis performance [12]. The general conclusions of these studies were that the great majority of lichens are highly desiccation tolerant, but they do not survive embedded in water for a few days. Dry thalli can resist heat, up to 60 °C, however, a hydrated thallus dies when the temperature exceeds 35 °C. Lichens can also tolerate extremely low temperatures (−196 °C) when dry and when hydrated if cooling is slow enough.

During the end of the 20th Century and beginning of the 21st, scientists focused on understanding the physiological processes that lie behind lichen tolerance to environmental stress. Most of the studies addressed the physiological responses to desiccation-induced oxidative stress. The intracellular overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can cause considerable cellular injuries by attacking nucleic acids, lipids, and proteins. It was argued by Kranner et al. [13] that “effective control of reactive oxygen species and mutual up-regulation of protective mechanisms was critically important for the evolution of lichens, facilitating the transition from free-living fungi and green algae or cyanobacteria to the lichenized state”. On one hand, the role of energy dissipation mechanisms against desiccation stress was investigated by employing chlorophyll fluorescence techniques and the quantification of xanthophylls by HPLC analysis. On the other hand, the response of ROS scavengers-enzymatic and low-molecular weight antioxidants during desiccation/rehydration (D/R) was studied by HPLC, electrophoretical, immunological and spectrophotometrical techniques. Comparative approaches with lichen species differing in DT suggested that, besides the antioxidant system, other mechanisms allowed lichens to survive desiccation [14][15].

The latest reviews on lichen DT (e.g., [5][13][16]) revealed that the knowledge about DT mechanisms was much scarcer than in other organisms tolerant to desiccation such as bryophytes or vascular resurrection plants. During the last decade, this gap has been reduced due to advances in molecular biology, particularly in the use of -omic technologies. The increasing availability of genomic, proteomic, transcriptomic and metabolomic data from lichens and their isolated symbionts have expanded our horizons and helped to gain insight into alternative lichen desiccation-tolerance mechanisms.

2. Advances in Understanding of Desiccation Tolerance of Lichens and Lichen-Forming Algae

During the last decade there has been a quantitative and qualitative leap in the knowledge of DT in lichens. This advance has been possible because of the onset of the use of “omics” techniques including genomics, proteomics, metabolomics and transcriptomics. These techniques have allowed us to deepen our knowledge of the role of the antioxidant system, sugar and polyol metabolism, and photoprotection mechanisms in desiccation tolerant lichens. Besides the insights in the aforementioned DT mechanisms, additional protection strategies, never described before in lichens, have been reported. Some of these strategies are changes in the lipid membrane composition, the remodeling of the cell wall and changes in EPS, cytoplasm vitrification during desiccation, etc. Moreover, transcriptomic data analyses have provided clues about other possible components contributing to DT in lichens such as aquaporins or DPS. Another important insight is the beginning of the decryption of the molecular signaling pathways (NO, PLD, MAPKs, etc.) that are behind the rapid response of lichen phycobionts to dehydration.

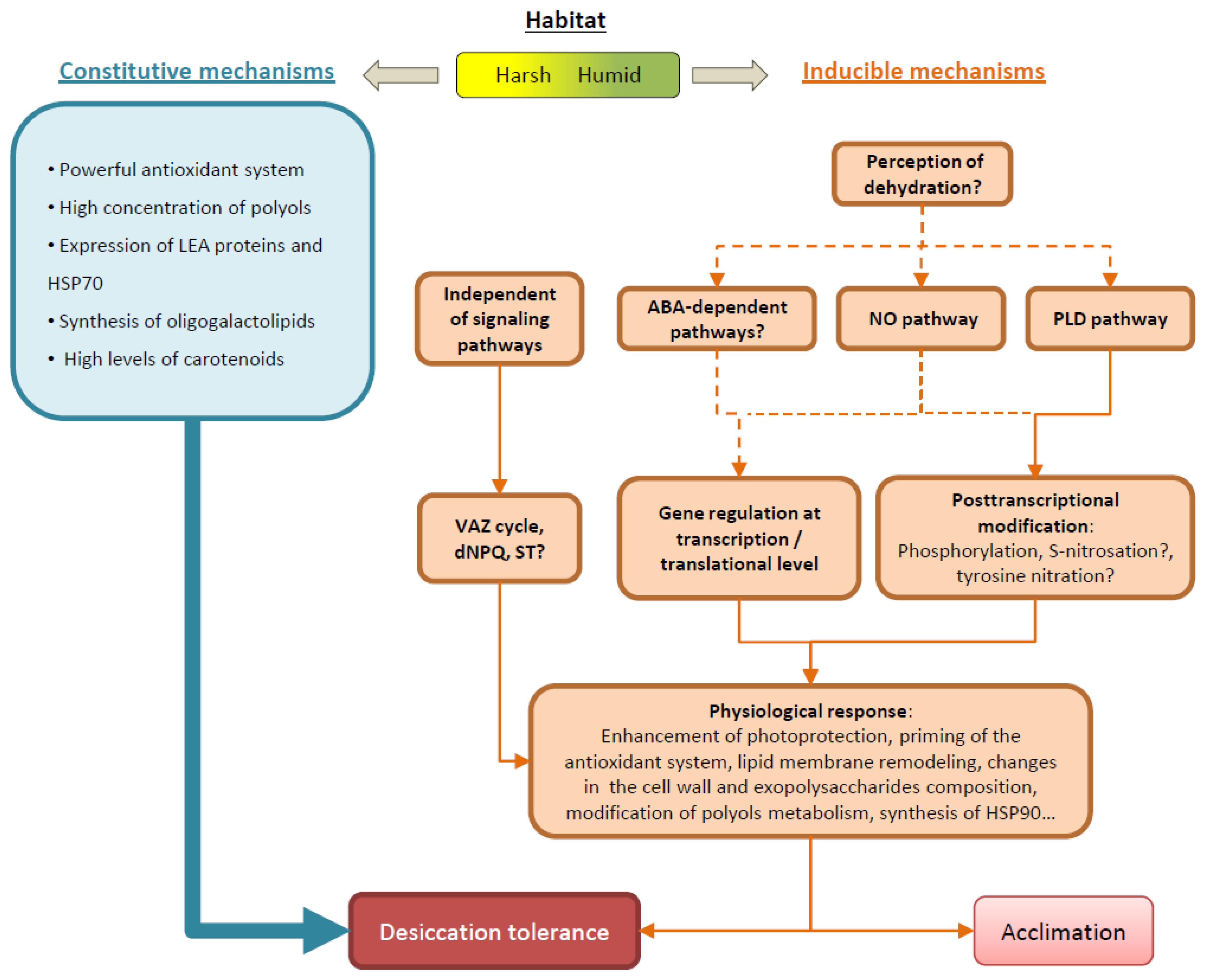

The compilation of previous and recent knowledge gives a clearer and detailed view of the molecular processes involved in the tolerance to desiccation of lichens (Figure 1). Desiccation-tolerance in lichens is mainly achieved by constitutive mechanisms, as it can be expected for poikilohydric organisms adapted to rapid fluctuation of hydration. However, there is increasing evidence that inducible responses during dehydration are also important. Inducible mechanisms would be particularly important for species growing in more humid and stable habitats, where constitutive mechanisms would have an unnecessary permanent energetic cost. Moreover, inducible factors could eventually contribute to acclimation and priming of physiological responses for a better adaption to changing environmental conditions. Several molecular signaling pathways might be involved in the transduction of the perception of water loss into physiological responses. The regulation of the function of proteins and enzymes may occur at different levels: (1) transcriptionally, up- or down-regulating the transcription of specific genes in response to D/R; (2) translationally, sequestering and stabilizing selected mRNA during desiccation to be translated into proteins upon rehydration; (3) through the activation/deactivation of enzymes by molecular modifications.

Figure 1. Lichen desiccation-tolerance (DT) is mainly achieved by constitutive mechanisms, although some physiological responses can also be induced during dehydration/rehydration. The relevance of constitutive and induced mechanisms may depend on adaption to habitat. In lichens growing in harsh habitats, DT relays mainly on constitutive mechanisms, whereas, in humid habitats, where drying occurs more slowly, lichens have enough time to induce cellular responses. The detection of cell water loss might trigger molecular signal cascades, such as the abscisic acid (ABA), nitric oxide (NO) and phospholipase D (PLD) pathways. Signaling pathways might regulate the expression of genes by the induction/inhibition of their transcription, or by the selective sequestration of specific mRNA that would be translated into proteins during rehydration. In addition, the activity of enzymes might be regulated by modifications such as phosphorylation. Besides regulation by signaling pathways, there are some physiochemical events indirectly caused by dehydration that can activate enzymatic reactions, such as the activation of the xanthophyll cycle (VAZ), the regulation of the photosynthetic state-transition (ST), or the activation of the desiccation non-photochemical quenching (dNPQ). The activation of these (and other) physiological responses would allow the cells to face a desiccation event in a better position, and to recover quickly upon rehydration. In this sense, priming of physiological responses could help lichens to acclimate to environmental conditions. For more detailed information see the text. Solid arrows depict known pathways, while dashed arrows indicate proposed or unknown pathways.

Despite the advances obtained during the last decade, there are still great challenges that remain unsolved. Among them, little is known about some key proteins involved in DT, such as LEAs or HSPs. Their study might be addressed through the genetic modification of the symbionts, or by comparative approaches employing symbionts differing in DT. Obviously, it is necessary to start the survey of specific DT components revealed by transcriptomic data analyses such as the aquaporins or DPRs. Another important challenge is to determine the DT degree of the different species/groups of phycobionts, and whether their selection might be related to the habitat. Finally, as the readers would have realised, the vast majority of DT studies have focused on lichen photobionts, through the analysis of particular parameters such as photosynthesis and plant pigments in lichen thalli, or directly working with in vitro algae cultures. The lack of specific studies with isolated mycobionts probably is due to the difficulty of their culture and manipulation, in comparison to microalgae. However, it is essential to begin the research in mycobionts since the fungus partner represents more than 90% of the biomass of a lichen thallus. The success of these goals will lead us to reach new horizons of knowledge in desiccation tolerance.

References

- Jahns, H.M. The lichen thallus. In CRC Handbook of Lichenology; Galun, M., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1988; pp. 95–143.

- Honegger, R.; Edwards, D.; Axe, L. The earliest records of internally stratified cyanobacterial and algal lichens from the Lower Devonian of the Welsh Borderland. New Phytol. 2013, 197, 264–275.

- Nelsen, M.P.; Lucking, R.; Boyce, C.K.; Lumbsch, H.T.; Ree, R.H. No support for the emergence of lichens prior to the evolution of vascular plants. Geobiology 2020, 18, 3–13.

- Morris, J.L.; Puttick, M.N.; Clark, J.W.; Edwards, D.; Kenrick, P.; Pressel, S.; Wellman, C.H.; Yang, Z.; Schneider, H.; Donoghue, P.C.J. The timescale of early land plant evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E2274–E2283.

- Beckett, R.P.; Kranner, I.; Minibayeva, F.V. Stress physiology and the symbiosis. In Lichen Biology; Nash, I., Thomas, H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 134–151.

- Larson, D.W. The absorption and release of water by lichens. Bibl. Lichenol. 1987, 25, 351–360.

- Kappen, L. Chapter 10-Response to extreme environments. In The Lichens; Ahmadjian, V., Hale, M.E., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1973; pp. 311–380.

- Smith, D.C. The Biology of Lichen Thalli. Biol. Rev. 1962, 37, 537–570.

- Thomas, E.A. Über die Biologie von Flechtenbildnern; Kommissionsverlag Buchdruckerei Büchler: Bern, Germany, 1939.

- Lange, O.L. Hitze- und Trockenresistenz der Flechten in Beziehung zu ihrer Verbreitung. Flora Oder Allg. Bot. Ztg. 1953, 140, 39–97.

- Jumelle, M.H. Recherches physiologiques sur les lichens. II/2. Influence de la proportion d’eau du lichen sur l’intensité des échanges gazeux. Rev. Gén. Bot. 1892, 4, 159–169.

- Jensen, M.; Kricke, R. Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements in the field: Assessment of the vitality of large numbers of lichen thalli. In Monitoring with Lichens-Monitoring Lichens; Nimis, P.L., Scheidegger, C., Wolseley, P.A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 327–332.

- Kranner, I.; Beckett, R.; Hochman, A.; Nash, T.H. Desiccation-tolerance in lichens: A review. Bryologist 2008, 111, 576–593.

- Kranner, I. Glutathione status correlates with different degrees of desiccation tolerance in three lichens. New Phytol. 2002, 154, 451–460.

- Kranner, I.; Zorn, M.; Turk, B.; Wornik, S.; Beckett, R.P.; Batič, F. Biochemical traits of lichens differing in relative desiccation tolerance. New Phytol. 2003, 160, 167–176.

- Gasulla, F.; Herrero, J.; Esteban-Carrasco, A.; Ros-Barceló, A.; Barreno, E.; Zapata, J.M.; Guéra, A. Photosynthesis in lichen: Light reactions and protective mechanisms. In Advances in Photosynthesis-Fundamental Aspects; Najafpour, M.M., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 149–174.