| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Katarzyna Skowrońska | + 5845 word(s) | 5845 | 2021-04-29 04:56:16 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | -2646 word(s) | 3199 | 2021-04-30 09:39:18 | | |

Video Upload Options

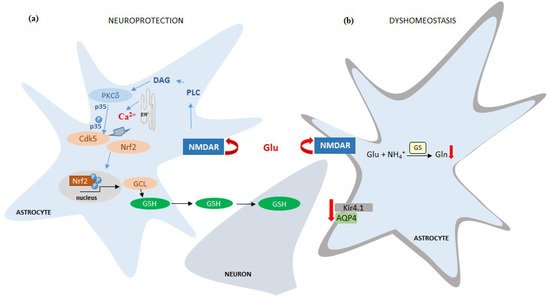

Studies of the last two decades have demonstrated the presence in astrocytic cell membranes of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (NMDARs), albeit their abundance in astrocytes appears to be strikingly lower than of other glutamate (Glu) receptor classes. Recent advancements in visualization techniques have enabled convincing demonstration of the activation of astrocytic NMDARs directly in brain slices and in acutely isolated or cultured astrocytes, by monitoring intracellular calcium increase. Astrocytic NMDARs are activated by mutually unexclusive ionotropic and metabotropic mechanisms.

1. Introduction

Research of the last few decades has promoted astrocytes from cells providing physical and metabolic support to neurons to being their indispensable partner in neurotransmission (for exhaustive reviews see [1][2]). One of the crucial tools which astrocytes use to communicate with neurons and to modulate their function are neurotransmitter receptors located on astrocytic cell membranes. Indeed, astrocytes are endowed with a rich repertoire of receptors for neuroactive amino acids, purines, and catecholamines, among these receptors recognizing glutamate (Glu), the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS). Like in neurons, Glu receptors present on astrocytes include metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) and the three classes of ionotropic receptors (iGluR): α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors (AMPAR), kainic acid (KA) receptors (KAR), and N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) [3][4][5]. Of these, the status of NMDARs is relatively least explored and has long been considered uncertain. Pioneering studies of the 1980s, which analysed electrophysiological and calcium flux-generating responses of astrocytes to Glu in primary cell culture preparations, failed to demonstrate the presence of functional NMDARs on astrocytes. While the responses to Glu could be mimicked by KA or the AMPAR agonist quisqualate, it was not the case with NMDA or Glu in the presence of NMDAR antagonists [6][7][8][9][10]. The advent of experiments on acutely isolated brain slices led first to detailed characterisation of astrocytic AMPAR [11], the responses of which to Glu differed between astrocytes (i) in brain slices and in culture [12], and (ii) recorded in two different loci of the same brain region (hippocampus) [13]. NMDA-mediated responses to Glu were first successfully recorded in astrocytes in brain slices and in astrocytes derived from the brain by the fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) technique [14], albeit interference of the direct response of astrocytes to NMDA by an indirect effect mediated by Glu transfer between astrocytes and neurons could not be excluded in this study. A study performed in acutely isolated astrocytes rendered the first description of NMDAR-mediated currents evoked in astrocytes by exogenously applied Glu [15]. From then on, one could witness considerable progress in understanding the nature of NMDARs residing in astrocytes, including their region-to-region and sub-regional heterogeneity with regard to their pharmacological and functional properties and feedback response to adjacent neurons. Independently, intensive work has led to the revival of cultured astrocytes as a valuable tool with which to study intracellular effects of stimulation of astrocytic NMDARs, including modulation of the responses by pathogenic events. This review accounts for hallmarks of the progress, but at the same time addresses questions that remain to be unraveled to appreciate how critical the role of these receptors is in CNS metabolism and functions. Three major issues will be in focus:

-

Subunit composition and assembly of NMDAR in astrocytes and the impact of the NMDAR composition on receptor functionality.

-

Ways in which astrocytic NMDARs respond to extrasynaptic Glu and translate the neuron-derived signal to modulation of neurotransmission.

-

The role of signals elicited by astrocytic NMDARs in regulating astroglia-specific intracellular metabolic events and in shaping the response of astrocytes to pathogenic stimuli.

Inconsistencies of the results obtained using different ex vivo and in vitro experimental settings and inherent limitations of the methodology used so far will be emphasised.

2. Subunit Composition and Properties of NMDAR in Astrocytes: Comparison to Neurons

Most of the current knowledge about the structure and functioning of NMDAR is derived from studies on neurons. Investigations on neurons revealed the existence of seven NMDAR subunits which form hetero-tetrameric transmembrane ion channels. They contain two GluN1 (In many earlier articles, GluN1, GluN2, and GluN3 have been designated interchangeably with NR1, NR2, and NR3. In this review, we will be exclusively using the terms GluN1, GluN2, and GluN3, which is now a generally accepted mode) subunits, which bind the co-agonist [glycine (Gly) or d-serine] and are linked to one or two GluN2 (A,B,C,D) subunits and one GluN3 (A,B) subunit. GluN2 are Glu-binding subunits, while GluN3 also binds Gly (or d-serine) [16][17]. GluN1 is the obligatory NMDAR subunit essential for the assembly and trafficking of other subunits, and for the formation of a functional NMDAR channel [18][19][20]. GluN3 acts in a dominant-negative manner to suppress receptor activity [21][22]. Overexpression of GluN3A protein results in the formation of GluN1/GluN3A channels that offer neuroprotection [23].

The neuronal NMDARs are classically composed of two GluN1 and two GluN2A or GluN2B. Two molecules of the co-agonist Gly [24][25] and two molecules of the agonist Glu are required for their activation ([26][27][28][29][30]; see [31] for a recent review). More rarely detected NMDAR variants include:

-

assemblies of GluN1 with GluN2C/D or GluN3A/B,

-

a heterodimer of GluN1 and GluN3A/B subunits that forms an excitatory Gly receptor (interaction with Gly is sufficient for their activation) [32][33].

-

a complex composed of GluN1/GluN2/GluN3 subunits that form an NMDAR producing lower currents compared to GluN1/GluN2 assemblies ([32][34][35][36][37], reviewed by [38]).

Each receptor subtype by itself exhibits temporal and regional specificity [39][40], and their unique functional properties are determined by the specific combination of subunits [41][42]. The subunit composition-dependent receptor properties include Glu affinity, receptor desensitisation, ion conductance, agonist affinity, sensitivity to allosteric modulation, and pharmacological sensitivity [27][38][42]. NMDARs possessing GluN2C/D subunits are less sensitive to Mg2+ block than those composed of GluN2A/B, and the combination of GluN3 subunit with GluN2 and GluN1 additionally reduces the sensitivity to Mg2+ and limits Ca2+ permeability [16][21][27][32][33][37][38][43]. Specifically, the presence of GluN3A subunit is critical for determination of the Mg2+ block and Ca2+ permeability of NMDARs [21][44][45][46].

Expression of NMDAR in astrocytes has been fairly reproducibly documented at the level of mRNA coding for the different subunits. Messenger RNAs for GluN1, GluN2A, and GluN2B subunits have been detected in cultured mouse [47] and rat [48] astrocytes. Moreover, transcripts for the GluN1, GluN2B, and GluN2C NMDAR subunits have been demonstrated in cortical astrocytes [14] and in Bergmann glia [49]. In mouse astrocytes in vivo, the presence of all NMDAR subunits at different expression levels was demonstrated [50], with GluN1, GluN2C, and GluN3A being the quantitatively dominating subunits [51][52][53][54]. Transcripts for all seven NMDAR subunits (i.e., GluN1, GluN2A-D, and GluN3A,B) have been found in cultured human [55], rat [56] and mouse astrocytes [Figure 1].

With regard to subunit proteins, immunohistochemical staining of brain slices combined with electron microscopic analysis demonstrated the expression in astrocytes from different rat brain regions of GluN1 [57][58][59][60][61] and GluN2A/B [57][60]. Moreover, the expression of GluN2C protein was documented in astrocytes from Grin2Ctm1 (EGFP/cre/ERT2)Wtsi mouse line [62]. A full set of 7 subunits was recorded in cultured rat [56] and human astrocytes [55]. The GluN1 subunit was detected by immunostaining in mouse cultured astrocytes [47][63], whereas GluN2B was detected in both mouse and rat astrocytes in vitro [47][64].

At the protein level (Western Blot method), so far only the expression of GluN1 [56], GluN2A, and GluN2B [48] subunits have been demonstrated in rat and GluN1 [65] subunit in mouse astrocytes in culture.

NMDARs expressed in astrocytes differ from neuronal NMDARs in their weak susceptibility of the channel to Mg2+ blockade (about −120mV) and reduced Ca2+ permeability (PCa/Pmonovalent ~3). The difference is most likely due to the relative overrepresentation of the tri-heteromeric (GluN1 + GluN2 + GluN3) configuration of NMDAR in astrocytes [15][31][38][52][66][67][68][69]. In one of the above-mentioned studies, functional NMDAR composed of GluN1 with one GluN2C or GluN2D subunit and one GluN3 subunit were identified in astrocytes [68]. Most recently, predominant expression of mRNA coding for the GluN2C subunit was reported in glial cells of the telencephalon [70]. In most studies, requirement of astrocytic NMDAR activity for the co-agonists Gly or d-serine has been reported ([15][52][68][71][72], however, see [56] for a contradictory observation).

3. Changes in Astrocytic NMDAR Subunit Expression in Brain Pathologies

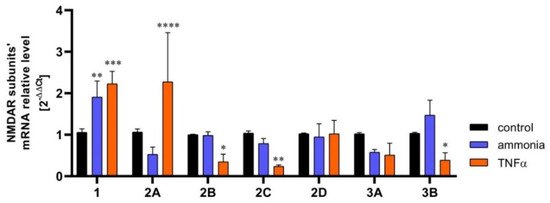

Krebs et al., (2003) [73] reported transient increase of the expression of the GluN1 and GluN2B NMDAR subunits in hippocampal astrocytes in a rat model of ischemia, induced by carotid artery clamping, but provided no mechanistic insight to this process. This study demonstrated a similar GluN2B overexpression in cultured hippocampal astrocytes in culture subjected to anoxia, corroborating the ex vivo studies. The response of astrocytic NMDARs to ischemia was further investigated by Zhou et al., (2010) [47]. The study, conducted on mouse cultured astrocytes, confirmed an increase in GluN2B expression modelled with oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD). However, the expression dynamics of GluN1 were biphasic; initially it increased, and then decreased below the control level at 6h. The GluN2A expression decrease became apparent at 4 h and remained low up to the 6th h. The pathophysiological implications of the above changes were not commented on by the authors and remain to be envisaged. Dzamba et al., (2015) [52] confirmed the involvement of astrocytic NMDARs in the pathomechanism of ischemia. They observed increased GluN3A subunit expression in astrocytes from the cerebral cortex of mice subjected to permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo). The astrocytes of ischemic animals also had impaired (diminished) Ca2+ response to NMDA as compared to sham-operated controls. Experiments from our own laboratory revealed changes in the expression of mRNA coding in a number of NMDAR subunits in astrocytes exposed to two neurotoxic factors: ammonia and the inflammatory cytokine TNFα (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The content of mRNA coding for NMDAR subunits in mouse cortical astrocytes cultured in control conditions and exposed for 72 h to 5 mM ammonia or 50 ng/ml TNFα treatment. Real-time PCR procedure was exactly as in Skowrońska et al., (2019) [63]. The mRNA expression was determined by TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems). The assay IDs were Mm00433790_m1 for GluN1 (Grin1); Mm00433802_m1 for GluN2A (Grin2a); Mm00433820_m1 for GluN2B (Grin2b); Mm00439180_m1 for GluN2C (Grin2c); Mm00433822_m1 for GluN2D (Grin2d); Mm01341723_m1 for GluN3A (Grin3a); Mm00504568_m1 for GluN3B (Grin3b); and Mm00607939_s1 for endogenous control β-actin. Results are mean ± SD (n = 3). (*) p < 0.05 vs control; (**) p < 0.01 vs control; (***) p < 0.001 vs control; (****) p < 0.0001 vs control; Two-Way ANOVA with Dunnett post-hoc test.

4. Mechanisms and Manifestations of NMDAR Activation in Astrocytes

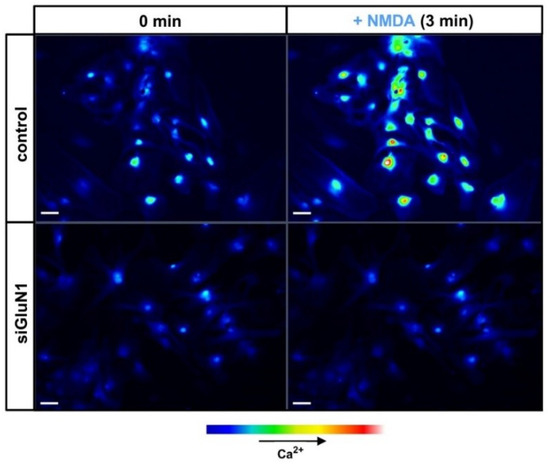

Extensive research of the last two decades has confirmed that astrocytes are able to respond to neuronal stimuli mediated by a variety of neurotransmitters, including Glu, and to modulate neuronal activity (reviewed in [1][2]). Unlike the metabotropic glutamatergic signalling in astrocytes, functionality of astrocytic NMDAR remains a matter of controversy due to the virtual lack of in situ experiments that would unequivocally confirm their role in CNS function. However, there is growing evidence from in vitro and ex vivo studies confirming that activation of NMDAR in astrocytes by Glu or selective NMDAR agonists mediates ion currents and intracellular calcium waves. NMDAR-evoked intracellular calcium accumulation in mouse cortical astrocytes before and after silencing of GluN1 with siRNA is illustrated in Figure 2.

NMDAR is a cationic channel with partial permeability for Ca2+. Accordingly, there has long been a consensus that influx from the extracellular space is the only mechanism by which stimulation of NMDAR increases intracellular Ca2+. The exclusivity of the ionotropic mechanism has been questioned in recent studies. In CA1 pyramidal neurons, in the presence of amyloid β (Aβ), NMDARs act as metabotropic receptors and activate intracellular signalling cascades in the absence of Ca2+ influx [74]. Such external Ca2+ flow-independent (metabotropic) NMDAR activity is also required for Aβ-induced synaptic depression [75][76][77]. In acute hippocampal slices, activation of NMDARs induced long-term depression (LTD) without ion flow through the receptors ([78][79][80][81], see [82] for a recent review). As will be described below, astrocytic NMDARs have likewise been observed to act through non-canonical, metabotropic signalling pathways.

Zhang et al., (2003) [83] and Hu et al., (2004) [84] have noted that in rat astrocytes, calcium increase, as a response to Glu, NMDA, or AMPA, was partially inhibited by the NMDAR antagonist: 2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoate (AP5) and AMPAR/KAR antagonist 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), indicating both NMDAR and AMPAR-dependence. While the sensitivity to lack of external Ca2+ supported the involvement of an ionotropic mechanism, the inhibition of Glu-induced Ca2+ flux by the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) SERCA ATPase blocker, thapsigargin, indicated that metabotropic response is involved as well. Similar conclusions could be drawn from a recent study by Montes de Oca Balderas and Aguilera (2015) [56]. In their hands, the NMDA-induced calcium entry to astrocytes was sensitive to NMDAR antagonists AP5 and kynurenic acid (KYNA) and was blocked by siRNA knockdown of the GluN1 subunit, supporting the ionotropic mechanism. However, the response turned out to be also sensitive to the antagonists of ryanodine and IP3 receptors, ryanodine, and xestospongin C, but not to the NMDAR channel blocker MK-801 or the absence of calcium in the medium. Furthermore, the group revealed that NMDAR activity is dependent on tyrosine kinase function (inhibition of the kinase by genistein potentiated the NMDA-induced calcium signal). In cultured human astrocytes (cerebral white matter biopsies from tumour margin), Nishizaki et al., (1999) [72] and subsequently Kondoh et al., (2001) [71] have detected two types of NMDA-induced ion currents, mediated both by iGluR (insensitive to GDPβS, a broad G-protein inhibitor, and sensitive to external calcium depletion) and mGluR (AP5 independent). The NMDA-induced currents were enhanced by ~40% by 5 μM Gly. Similar evidence for the concurrence of the ionotropic and metabotropic mechanism of the NMDAR activity has also been reported in cultured rat astrocytes subjected to an inflammatory stimulus [64]. The physiological meaning of the dual mechanism remains to be elucidated. As a prerequisite, the duality must be proven in the in vivo setting. As a note of caution, it is not certain whether the metabotropic mechanism operates in all experimental contexts or preparations. In human foetal and adult cultured astrocytes, stimulation of intracellular Ca2+ accumulation by selective NMDAR agonists quinolinic acid (QUIN) and trans-ACBD was virtually abolished by NMDAR channel blockers memantine or MK-801 [55].

While Ca2+ influx is a commonly used marker of NMDAR activity in astrocytes, in one case known to us, a different marker was employed. ATP release from astrocytes, which is regarded as a major pathway employed in glia-neuron interaction, termed gliotransmission [85], is mainly triggered by activation of glutamatergic or purinergic metabotropic receptors [1]. However, as early as 1997, the group of von Kügelgen showed that NMDA (100 μM) induces ATP release in rat cortical astrocytes in culture [86]. The effect was blocked by a selective NMDAR antagonist, AP5, and was abolished or greatly reduced in the absence of external calcium [86][87]. Investigation of this interesting phenomenon has so far not been continued by others.

The activity of NMDAR residing on astrocytes have been also verified and confirmed in different preparations of brain slices. In their pioneering work on acutely isolated rat spinal cord slices, in which cell membrane currents were recorded using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique, Ziak et al., (1998) [88] established that astrocytic NMDARs are characterised by lack of Mg2+ blockade and inhibition in the absence of external Ca2+. Schipke et al., (2001) [14] showed NMDA-induced inward ion currents in mouse cortical astrocytes selectively expressing an enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP). The currents were almost completely and irreversibly blocked by MK-801. Moreover, using microinjected fluorescent calcium dye Fluo-4-AM, the authors showed an increase in intracellular calcium, evoked by NMDA application. Both the ion currents and Ca2+ response were dependent on neuronal function, as demonstrated by tetradotoxin (TTX) sensitivity. In a similar experimental setting, Lalo et al., (2006) [15] confirmed the ability of NMDA to induce ion currents in astrocytes. They also showed that Glu evokes two types of current response, resulting from iGluR and Glu transporters, respectively. The iGluR involved were mostly NMDARs, and to much lesser extent, AMPAR. Additionally, the analysis of astrocytic NMDAR properties performed by Lalo et al., (2006) [15] revealed that NMDA-mediated currents are potentiated by the co-agonist Gly, but unlike in neuronal NMDAR, are insensitive to magnesium blockade. Moreover, astrocytes exhibited spontaneous miniature currents, both NMDA- and AMPA-mediated, in the presence of TTX or picrotoxin. The miniature currents were sensitive to NMDAR antagonists but not to the Glu transporter inhibitor, dl-threo-β-benzyloxyaspartate (TBOA). The presence of miniature potentials bespeaks local, direct neuron-glia communication. Palygin et al., (2011) [68] recorded NMDA-evoked, Gly and d-serine dependent (weak agonism) ionic currents in astrocytes analysed either directly in slices or following their acute isolation from mouse cerebral cortex. The responses were reduced by NMDAR antagonists UBP141, memantine and MK-801, but not by one other antagonist, ifenprodil. The Ca2+ permeability of astrocytic NMDAR was lower than of the neuronal NMDAR, and the Mg2+ block was absent. As mentioned earlier, such response pattern was a good fit into the model of NMDAR in murine cortical astrocytes, being a tri-heteromer assembled of not only GluN1 and GluN2 but also GluN3, a subunit responsible for both relatively low Ca2+ permeability and lack of Mg2+ block. As is to be recalled from Section 2, the presence of GluN3 in astrocytic NMDAR has been confirmed in different astrocytic preparations.

Abbreviations

| AMPA | α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid |

| AMPAR | AMPA receptors |

| AP5 | 2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoate |

| AQP4 | Aquaporin-4 |

| Cdk5 | Cyclin-dependent kinase-5 |

| CNQX | 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| EGFP | Enhanced green fluorescence protein |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| FACS | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting |

| Glu | Glutamate |

| GluN | Subunit of NMDAR |

| Gly | Glycine |

| GS | Glutamine synthetase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| iGluR | Ionotropic glutamate receptors |

| KA | Kainic acid |

| KAR | KA receptors |

| KYNA | Kynurenic acid |

| LTD | Long-term depression |

| MCAo | Middle cerebral artery occlusion |

| mGluR | Metabotropic glutamate receptors |

| NMDA | N-methyl-d-aspartate |

| NMDAR | NMDA receptor |

| NMDARs | NMDA receptors |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor-2 |

| OGD | Oxygen-glucose deprivation |

| QUIN | Quinolinic acid |

| TBOA | dl-threo-β-benzyloxyaspartate |

| TTX | Tetradotoxin |

References

- Hamilton, N.B.; Attwell, D. Do astrocytes really exocytose neurotransmitters? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 227–238.

- Verkhratsky, A.; Nedergaard, M. Physiology of Astroglia. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 239–389.

- Hadzic, M.; Jack, A.; Wahle, P. Ionotropic glutamate receptors: Which ones, when, and where in the mammalian neocortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 2017, 525, 976–1033.

- Willard, S.S.; Koochekpour, S. Glutamate, glutamate receptors, and downstream signaling pathways. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2013, 9, 948–959.

- Zhu, S.; Gouaux, E. Structure and symmetry inform gating principles of ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112, 11–15.

- Backus, K.; Kettenmann, H.; Schachner, M. Pharmacological characterization of the glutamate receptor in cultured astrocytes. J. Neurosci. Res. 1989, 22, 274–282.

- Bowman, C.L.; Kimelberg, H.K. Excitatory amino acids directly depolarize rat brain astrocytes in primary culture. Nature 1984, 311, 656–659.

- Kettenmann, H.; Schachner, M. Pharmacological properties of gamma-aminobutyric acid-, glutamate-, and aspartate-induced depolarizations in cultured astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 1985, 5, 3295–3301.

- Pearce, B.; Albrecht, J.; Morrow, C.; Murphy, S. Astrocyte glutamate receptor activation promotes inositol phospholipid turnover and calcium flux. Neurosci. Lett. 1986, 72, 335–340.

- Sontheimer, H.; Kettenmann, H.; Backus, K.H.; Schachner, M. Glutamate opens Na+/K+ channels in cultured astrocytes. Glia 1988, 1, 328–336.

- Cai, Z.; Kimelberg, H.K. Glutamate receptor-mediated calcium responses in acutely isolated hippocampal astrocytes. Glia 1997, 21, 380–389.

- Kimelberg, H.K.; Cai, Z.; Rastogi, P.; Charniga, C.J.; Goderie, S.; Dave, V.; Jalonen, T.O. Transmitter-induced calcium responses differ in astrocytes acutely isolated from rat brain and in culture. J. Neurochem. 1997, 68, 1088–1098.

- Zhou, M.; Kimelberg, H.K. Freshly isolated hippocampal CA1 astrocytes comprise two populations differing in glutamate transporter and AMPA receptor expression. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 7901–7908.

- Schipke, C.G.; Ohlemeyer, C.; Matyash, M.; Nolte, C.; Kettenmann, H.; Kirchhoff, F. Astrocytes of the mouse neocortex express functional N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 1270–1272.

- Lalo, U.; Pankratov, Y.; Kirchhoff, F.; North, R.A.; Verkhratsky, A. NMDA receptors mediate neuron-to-glia signaling in mouse cortical astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 2673–2683.

- Traynelis, S.F.; Wollmuth, L.P.; McBain, C.J.; Menniti, F.S.; Vance, K.M.; Ogden, K.K.; Hansen, K.B.; Yuan, H.; Myers, S.J.; Dingledine, R. Glutamate receptor ion channels: Structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacol. Rev. 2010, 62, 405–496.

- Vyklicky, V.; Korinek, M.; Smejkalova, T.; Balik, A.; Krausova, B.; Kaniakova, M.; Lichnerova, K.; Cerny, J.; Krusek, J.; Dittert, I.; et al. Structure, function, and pharmacology of NMDA receptor channels. Physiol. Res. 2014, 63, S191–S203.

- Atlason, P.T.; Garside, M.L.; Meddows, E.; Whiting, P.; McIlhinney, R.A. N-Methyl-D aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunit NR1 forms the substrate for oligomeric assembly of the NMDA receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 25299–25307.

- Fukaya, M.; Kato, A.; Lovett, C.; Tonegawa, S.; Watanabe, M. Retention of NMDA receptor NR2 subunits in the lumen of endoplasmic reticulum in targeted NR1 knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 4855–4860.

- Schüler, T.; Mesic, I.; Madry, C.; Bartholomäus, I.; Laube, B. Formation of NR1/NR2 and NR1/NR3 heterodimers constitutes the initial step in N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 37–46.

- Henson, M.A.; Roberts, A.C.; Pérez-Otaño, I.; Philpot, B.D. Influence of the NR3A subunit on NMDA receptor functions. Prog. Neurobiol. 2010, 91, 23–37.

- Low, C.M.; Wee, K.S. New insights into the not-so-new NR3 subunits of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor: Localization, structure, and function. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010, 78, 1–11.

- Nakanishi, N.; Tu, S.; Shin, Y.; Cui, J.; Kurokawa, T.; Zhang, D.; Chen, H.S.; Tong, G.; Lipton, S.A. Neuroprotection by the NR3A subunit of the NMDA receptor. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 5260–5265.

- Johnson, J.W.; Ascher, P. Glycine potentiates the NMDA response in cultured mouse brain neurons. Nature 1987, 325, 529–531.

- Kleckner, N.W.; Dingledine, R. Requirement for glycine in activation of NMDA-receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Science 1988, 241, 835–837.

- Clements, J.D.; Westbrook, G.L. Activation kinetics reveal the number of glutamate and glycine binding sites on the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. Neuron 1991, 7, 605–613.

- Cull-Candy, S.G.; Leszkiewicz, D.N. Role of distinct NMDA receptor subtypes at central synapses. Sci. STKE 2004, 2004, re16.

- Patneau, D.K.; Mayer, M.L. Structure-activity relationships for amino acid transmitter candidates acting at N-methyl-D-aspartate and quisqualate receptors. J. Neurosci. 1990, 10, 2385–2399.

- Rambhadran, A.; Gonzalez, J.; Jayaraman, V. Subunit arrangement in N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 15296–15301.

- Watkins, J.C.; Evans, R.H. Excitatory amino acid transmitters. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1981, 21, 165–204.

- Hogan-Cann, A.D.; Anderson, C.M. Physiological roles of non-neuronal NMDA receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 37, 750–767.

- Chatterton, J.E.; Awobuluyi, M.; Premkumar, L.S.; Takahashi, H.; Talantova, M.; Shin, Y.; Cui, J.; Tu, S.; Sevarino, K.A.; Nakanishi, N.; et al. Excitatory glycine receptors containing the NR3 family of NMDA receptor subunits. Nature 2002, 415, 793–798.

- Pachernegg, S.; Strutz-Seebohm, N.; Hollmann, M. GluN3 subunit-containing NMDA receptors: Not just one-trick ponies. Trends Neurosci. 2012, 35, 240–249.

- Ciabarra, A.M.; Sullivan, J.M.; Gahn, L.G.; Pecht, G.; Heinemann, S.; Sevarino, K.A. Cloning and characterization of chi-1: A developmentally regulated member of a novel class of the ionotropic glutamate receptor family. J. Neurosci. 1995, 15, 6498–6508.

- Das, S.; Sasaki, Y.F.; Rothe, T.; Premkumar, L.S.; Takasu, M.; Crandall, J.E.; Dikkes, P.; Conner, D.A.; Rayudu, P.V.; Cheung, W.; et al. Increased NMDA current and spine density in mice lacking the NMDA receptor subunit NR3A. Nature 1998, 393, 377–381.

- Sucher, N.J.; Akbarian, S.; Chi, C.L.; Leclerc, C.L.; Awobuluyi, M.; Deitcher, D.L.; Wu, M.K.; Yuan, J.P.; Jones, E.G.; Lipton, S.A. Developmental and regional expression pattern of a novel NMDA receptor-like subunit (NMDAR-L) in the rodent brain. J. Neurosci. 1995, 15, 6509–6520.

- Tong, G.; Takahashi, H.; Tu, S.; Shin, Y.; Talantova, M.; Zago, W.; Xia, P.; Nie, Z.; Goetz, T.; Zhang, D.; et al. Modulation of NMDA receptor properties and synaptic transmission by the NR3A subunit in mouse hippocampal and cerebrocortical neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2008, 99, 122–132.

- Paoletti, P.; Bellone, C.; Zhou, Q. NMDA receptor subunit diversity: Impact on receptor properties, synaptic plasticity and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 383–400.

- Monyer, H.; Burnashev, N.; Laurie, D.J.; Sakmann, B.; Seeburg, P.H. Developmental and regional expression in the rat brain and functional properties of four NMDA receptors. Neuron 1994, 12, 529–540.

- Sheng, M.; Cummings, J.; Roldan, L.A.; Jan, Y.N.; Jan, L.Y. Changing subunit composition of heteromeric NMDA receptors during development of rat cortex. Nature 1994, 368, 144–147.

- Monyer, H.; Sprengel, R.; Schoepfer, R.; Herb, A.; Higuchi, M.; Lomeli, H.; Burnashev, N.; Sakmann, B.; Seeburg, P.H. Heteromeric NMDA receptors: Molecular and functional distinction of subtypes. Science 1992, 256, 1217–1221.

- Paoletti, P.; Neyton, J. NMDA receptor subunits: Function and pharmacology. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2007, 7, 39–47.

- Paoletti, P. Molecular basis of NMDA receptor functional diversity. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2011, 33, 1351–1365.

- Cavara, N.A.; Hollmann, M. Shuffling the deck anew: How NR3 tweaks NMDA receptor function. Mol. Neurobiol. 2008, 38, 16–26.

- Kehoe, L.A.; Bernardinelli, Y.; Muller, D. GluN3A: An NMDA receptor subunit with exquisite properties and functions. Neural Plast. 2013, 2013, 145387.

- Pérez-Otaño, I.; Larsen, R.S.; Wesseling, J.F. Emerging roles of GluN3-containing NMDA receptors in the CNS. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 623–635.

- Zhou, Y.; Li, H.L.; Zhao, R.; Yang, L.T.; Dong, Y.; Yue, X.; Ma, Y.Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Cui, C.L.; et al. Astrocytes express N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits in development, ischemia and post-ischemia. Neurochem. Res. 2010, 35, 2124–2134.

- Jimenez-Blasco, D.; Santofimia-Castaño, P.; Gonzalez, A.; Almeida, A.; Bolaños, J.P. Astrocyte NMDA receptors’ activity sustains neuronal survival through a Cdk5-Nrf2 pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 1877–1889.

- Luque, J.M.; Richards, J.G. Expression of NMDA 2B receptor subunit mRNA in Bergmann glia. Glia 1995, 13, 228–232.

- Rusnakova, V.; Honsa, P.; Dzamba, D.; Ståhlberg, A.; Kubista, M.; Anderova, M. Heterogeneity of astrocytes: From development to injury—Single cell gene expression. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69734.

- Cahoy, J.D.; Emery, B.; Kaushal, A.; Foo, L.C.; Zamanian, J.L.; Christopherson, K.S.; Christopherson, K.S.; Xing, Y.; Lubischer, J.L.; Krieg, P.A.; et al. A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: A new resource for understanding brain development and function. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 264–278.

- Dzamba, D.; Honsa, P.; Valny, M.; Kriska, J.; Valihrach, L.; Novosadova, V.; Kubista, M.; Anderova, M. Quantitative analysis of glutamate receptors in glial cells from the cortex of GFAP/EGFP mice following ischemic injury: Focus on NMDA receptors. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015, 35, 1187–1202.

- Orre, M.; Kamphuis, W.; Osborn, L.M.; Melief, J.; Kooijman, L.; Huitinga, I.; Klooster, J.; Bossers, K.; Hol, E.M. Acute isolation and transcriptome characterization of cortical astrocytes and microglia from young and aged mice. Neurobiol. Aging 2014, 35, 1–14.

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, K.; Sloan, S.A.; Bennett, M.L.; Scholze, A.R.; O’Keeffe, S.; Phatnani, H.P.; Guarnieri, P.; Caneda, C.; Ruderisch, N.; et al. An RNA sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 11929–11947.

- Lee, M.C.; Ting, K.K.; Adams, S.; Brew, B.J.; Chung, R.; Guillemin, G.J. Characterisation of the expression of NMDA receptors in human astrocytes. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14123.

- Montes de Oca Balderas, P.; Aguilera, P. A metabotropic-like flux-independent NMDA receptor regulates Ca2+ exit from endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial membrane potential in cultured astrocytes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126314.

- Conti, F.; DeBiasi, S.; Minelli, A.; Melone, M. Expression of NR1 and NR2A/B subunits of the NMDA receptor in cortical astrocytes. Glia 1996, 17, 254–258.

- Farb, C.R.; Aoki, C.; Ledoux, J.E. Differential localization of NMDA and AMPA receptor subunits in the lateral and basal nuclei of the amygdala: A light and electron microscopic study. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995, 362, 86–108.

- Gracy, K.N.; Pickel, V.M. Comparative ultrastructural localization of the NMDAR1 glutamate receptor in the rat basolateral amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995, 362, 71–85.

- Petralia, R.S.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhao, H.M.; Wenthold, R.J. Ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors show unique postsynaptic, presynaptic, and glial localizations in the dorsal cochlear nucleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996, 372, 356–383.

- Van Bockstaele, E.J.; Colago, E.E.O. Selective distribution of the NMDA-R1 glutamate receptor in astrocytes and presynaptic axon terminals in the nucleus locus coeruleus of the rat brain: An immunoelectron microscopic study. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996, 369, 483–496.

- Ravikrishnan, A.; Gandhi, P.J.; Shelkar, G.P.; Liu, J.; Pavuluri, R.; Dravid, S.M. Region-specific Expression of NMDA Receptor GluN2C Subunit in Parvalbumin-Positive Neurons and Astrocytes: Analysis of GluN2C Expression using a Novel Reporter Model. NeuroScience 2018, 380, 49–62.

- Skowrońska, K.; Obara-Michlewska, M.; Czarnecka, A.; Dąbrowska, K.; Zielińska, M.; Albrecht, J. Persistent Overexposure to N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) Calcium-Dependently Downregulates Glutamine Synthetase, Aquaporin 4, and Kir4.1 Channel in Mouse Cortical Astrocytes. Neurotox Res. 2019, 35, 271–280.

- Gerard, F.; Hansson, E. Inflammatory activation enhances NMDA-triggered Ca2+ signalling and IL-1β secretion in primary cultures of rat astrocytes. Brain Res. 2012, 1473, 1–8.

- Skowrońska, K.; Kozłowska, H.; Albrecht, J. Neuron-derived factors negatively modulate ryanodine receptor-mediated calcium release in cultured mouse astrocytes. Cell Calcium. 2020, 92, 102304.

- Lalo, U.; Pankratov, Y.; Parpura, V.; Verkhratsky, A. Ionotropic receptors in neuronal-astroglial signalling: What is the role of “excitable” molecules in non-excitable cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1813, 992–1002.

- Palygin, O.; Lalo, U.; Verkhratsky, A.; Pankratov, Y. Ionotropic NMDA and P2X1/5 receptors mediate synaptically induced Ca2+ signalling in cortical astrocytes. Cell Calcium. 2010, 48, 225–231.

- Palygin, O.; Lalo, U.; Pankratov, Y. Distinct pharmacological and functional properties of NMDA receptors in mouse cortical astrocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 1755–1766.

- Verkhratsky, A.; Kirchhoff, F. Glutamate-mediated neuronal-glial transmission. J. Anat. 2007, 210, 651–660.

- Alsaad, H.A.; DeKorver, N.W.; Mao, Z.; Dravid, S.M.; Arikkath, J.; Monaghan, D.T. In the Telencephalon, GluN2C NMDA Receptor Subunit mRNA is Predominately Expressed in Glial Cells and GluN2D mRNA in Interneurons. Neurochem. Res. 2018.

- Kondoh, T.; Nishizaki, T.; Aihara, H.; Tamaki, N. NMDA-responsible, APV-insensitive receptor in cultured human astrocytes. Life Sci. 2001, 68, 1761–1767.

- Nishizaki, T.; Matsuoka, T.; Nomura, T.; Kondoh, T.; Tamaki, N.; Okada, Y. Store Ca2+ depletion enhances NMDA responses in cultured human astrocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 259, 661–664.

- Krebs, C.; Fernandes, H.B.; Sheldon, C.; Raymond, L.A.; Baimbridge, K.G. Functional NMDA receptor subtype 2B is expressed in astrocytes after ischemia in vivo and anoxia in vitro. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 3364–3372.

- Tamburri, A.; Dudilot, A.; Licea, S.; Bourgeois, C.; Boehm, J. NMDA-receptor activation but not ion flux is required for amyloid-beta induced synaptic depression. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65350.

- Birnbaum, J.H.; Bali, J.; Rajendran, L.; Nitsch, R.M.; Tackenberg, C. Calcium flux-independent NMDA receptor activity is required for Aβ oligomer-induced synaptic loss. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1791.

- Kessels, H.W.; Nabavi, S.; Malinow, R. Metabotropic NMDA receptor function is required for β-amyloid induced synaptic depression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4033–4038.

- Weilinger, N.L.; Lohman, A.W.; Rakai, B.D.; Ma, E.M.; Bialecki, J.; Maslieieva, V.; Rilea, T.; Bandet, M.V.; Ikuta, N.T.; Scott, L.; et al. Metabotropic NMDA receptor signaling couples Src family kinases to pannexin-1 during excitotoxicity. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 432–442.

- Carter, B.C.; Jahr, C.E. Postsynaptic, not presynaptic NMDA receptors are required for spike-timing-dependent LTD induction. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 1218–1224.

- Dore, K.; Aow, J.; Malinow, R. Agonist binding to the NMDA receptor drives movement of its cytoplasmic domain without ion flow. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 14705–14710.

- Nabavi, S.; Kessels, H.W.; Alfonso, S.; Aow, J.; Fox, R.; Malinow, R. Metabotropic NMDA receptor function is required for NMDA receptor-dependent long-term depression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4027–4032.

- Stein, I.S.; Gray, J.A.; Zito, K. Non-Ionotropic NMDA Receptor Signaling Drives Activity-Induced Dendritic Spine Shrinkage. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 12303–12308.

- Dore, K.; Aow, J.; Malinow, R. The Emergence of NMDA Receptor Metabotropic Function: Insights from Imaging. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2016, 8, 20.

- Zhang, Q.; Hu, B.; Sun, S.; Tong, E. Induction of increased intracellular calcium in astrocytes by glutamate through activating NMDA and AMPA receptors. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Med. Sci. 2003, 23, 254–257.

- Hu, B.; Sun, S.G.; Tong, E.T. NMDA and AMPA receptors mediate intracellular calcium increase in rat cortical astrocytes. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2004, 25, 714–720.

- Perea, G.; Navarrete, M.; Araque, A. Tripartite synapses: Astrocytes process and control synaptic information. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 421–431.

- Queiroz, G.; Gebicke-Haerter, P.J.; Schobert, A.; Starke, K.; von Kügelgen, I. Release of ATP from cultured rat astrocytes elicited by glutamate receptor activation. NeuroScience 1997, 78, 1203–1208.

- Queiroz, G.; Meyer, D.K.; Meyer, A.; Starke, K.; von Kügelgen, I. A study of the mechanism of the release of ATP from rat cortical astroglial cells evoked by activation of glutamate receptors. NeuroScience 1999, 91, 1171–1181.

- Ziak, D.; Chvátal, A.; Syková, E. Glutamate-, kainate- and NMDA-evoked membrane currents in identified glial cells in rat spinal cord slice. Physiol. Res. 1998, 47, 365–375.

- Obara-Michlewska, M.; Ruszkiewicz, J.; Zielińska, M.; Verkhratsky, A.; Albrecht, J. Astroglial NMDA receptors inhibit expression of Kir4.1 channels in glutamate-overexposed astrocytes in vitro and in the brain of rats with acute liver failure. Neurochem. Int. 2015, 88, 20–25.