Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Raf Sciot | + 1585 word(s) | 1585 | 2021-04-29 09:51:58 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | -5 word(s) | 1580 | 2021-04-29 11:16:09 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Sciot, R. MDM2 Amplified Sarcomas. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/9191 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Sciot R. MDM2 Amplified Sarcomas. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/9191. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Sciot, Raf. "MDM2 Amplified Sarcomas" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/9191 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Sciot, R. (2021, April 29). MDM2 Amplified Sarcomas. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/9191

Sciot, Raf. "MDM2 Amplified Sarcomas." Encyclopedia. Web. 29 April, 2021.

Copy Citation

Murine Double Minute Clone 2, located at 12q15, is an oncogene that codes for an oncoprotein of which the association with p53 was discovered 30 years ago. The most important function of MDM2 is to control p53 activity. The sarcomas that typically have an amplification of MDM2.

MDM2 amplification

well-differentiated liposarcoma/atypical lipomatous tumor

dedifferentiated liposarcoma

1. Introduction

Murine Double Minute Clone 2 is an oncogene, the function of which was first described in DNA associated with paired acentric chromatin bodies, termed double minutes, harbored in spontaneously transformed mouse 3T3 fibroblasts [1]. MDM2 (located at 12q15) codes for an oncoprotein of which the association with p53 was discovered 30 years ago. The protein functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets the p53 protein for proteasomal degradation. Thus, the most important function of MDM2 is to control p53 activity; it is in fact the best documented negative regulator of p53. For normal cells, it is of utmost importance that p53 is maintained at low levels since p53 has potent growth suppressive activities. In fact, p53 is lethal in the absence of MDM2. Mouse MDM2−/− embryos are inviable and deletion of p53 rescues these embryos. There are different mechanisms by which MDM2 can block p53 activity. On the one hand, MDM2 stimulates the degradation of p53 by escorting p53 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and by catalyzing the ubiquitination of p53 and hence, proteosomal degradation. On the other hand, MDM2 blocks the activity of intact p53 by inhibiting the p53 transactivation domain. Indeed, it is well known that p53 trans-activates a number of genes that mediate cell cycle arrest or apoptosis [1]. The oncogenic activities of MDM2 extend beyond the regulation of p53. Thus, MDM2-mediated ubiquitination of various transcription factors (ATF, E2F and others), of the retinoblastoma protein, and the histones H2A and H2B can influence cell proliferation, DNA repair, transcription, ribosome biosynthesis and cell fate. In addition, chromatin-bound MDM2 plays a key role in serine metabolism [2].

2. Well-Differentiated Liposarcoma/Atypical Lipomatous Tumor (WDL/ATL)

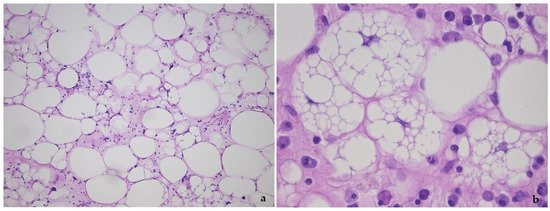

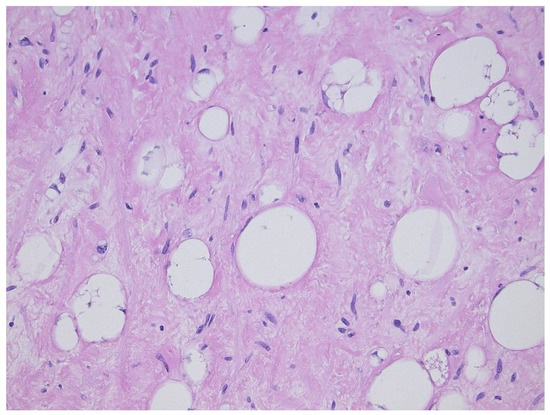

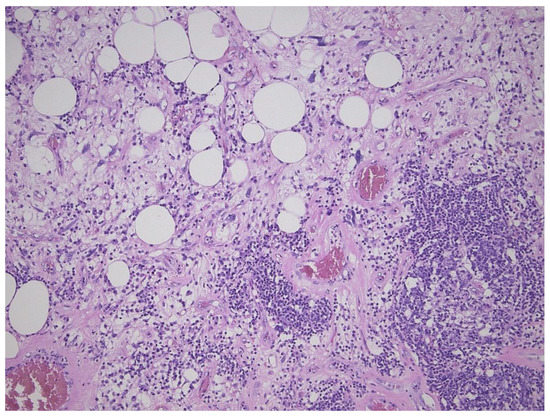

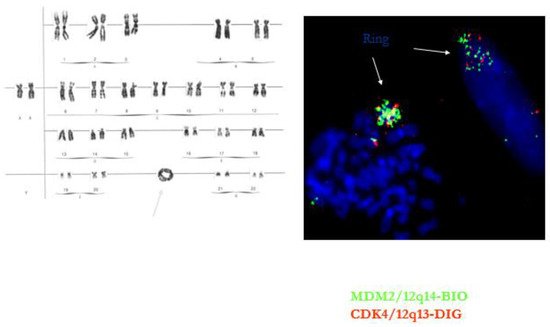

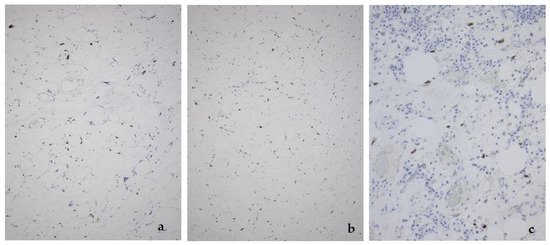

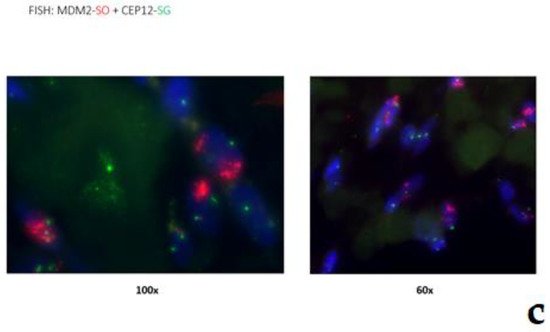

This tumor represents the most common malignant adipocytic neoplasm and is mainly seen in middle-aged adults. The deep soft tissues of the extremities are most frequently involved (75%), followed by the retroperitoneum (20%). The groin, paratesticulum and mediastinum are also known locations. The overall mortality is zero for lesions of the extremities and more than 80% for exactly the same tumors in the retroperitoneum. Therefore, the term “atypical lipomatous tumor” is used for lesions in surgically amenable sites where excision can be curative, like the extremities, and “well differentiated liposarcoma” for tumors presenting in the retroperitoneum, spermatic cord and mediastinum, where complete removal is often not possible leading to high morbidity and mortality. Three morphological subtypes are classically described: lipoma-like, sclerosing and inflammatory [3]. In the lipoma-like variant, the basic morphological hallmark is the presence of variation in adipocyte diameter, hyperchromatic/atypical nuclei and lipoblasts (Figure 1). In the sclerosing variant, scattered bizarre hyperchromatic cells and lipoblasts are seen in an extensive fibrillary stroma, varying from dens to myxoid (Figure 2). This subtype is most often seen in the retroperitoneum or paratesticular area. In the inflammatory variant, mainly seen in the retroperitoneum, a lymphoplasmocytic inflammatory infiltrate predominates and obscures the adipocytic component, to the extent that it can mimic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, Castleman’s disease or even a lymphoma (Figure 3). These phenotypic variants can be admixed in the same tumor. Whatever it looks like, WDL/ATL is characterized by giant marker and/or supernumerary ring chromosomes, both of which contain multiple copies of MDM2. This amplification results in nuclear MDM2 protein overexpression. There is frequently co-amplification of other genes of the 12q14-15 region, like CDK4, GLI1 and HMGA2, but MDM2 amplification is the main driver (Figure 4). Immunohistochemistry and/or FISH for MDM2 is frequently used to support the diagnosis of WDL/ATL, FISH being much more sensitive and specific than protein detection (Figure 5) [4][5]. MDM2 RNA ISH seems to be as performant as DNA FISH [6]. An important pitfall is the presence of nuclear MDM2 immunoreactivity in histiocytes/lipophages which are very often seen in traumatized fatty tumors. In addition, any cytoplasmic positivity is not diagnostic. The pathologist is often faced with lesions in which the histological changes are not convincing enough for WDL/ATL and thus, the differential diagnosis with an ordinary lipoma cannot be made on morphological grounds alone. This does not mean that every lipoma should be FISHed for MDM2, the following features justify the use of this test: (1) recurrent lesion, (2) deep extremity lesion larger than 10 cm in a patient over 50 years of age, (3) lesion with equivocal atypia, (4) lesion in the retroperitoneum/pelvis/abdomen, and (5) lesions not fitting the above criteria but having worrisome clinical or radiological features [7].

Figure 1. Lipoma-like variant of well-differentiated liposarcoma/atypical lipomatous tumor, showing the variation in adipocyte size, hyperchromatic nuclei and lipoblasts (a), detail of lipoblasts with the typical punched-out nucleus in (b).

Figure 2. Sclerosing variant of well-differentiated liposarcoma/atypical lipomatous tumor, highlighting the scattered lipoblasts in a sclerotic background.

Figure 3. Inflammatory variant of well-differentiated liposarcoma/atypical lipomatous tumor, dominated by a prominent lymphoplasmocytic infiltration. Note the atypical fat cells as well.

Figure 4. Ring chromosome in well-differentiated liposarcoma/atypical lipomatous tumor. The ring contains multiple copies of the MDM2 and CDK4 gene.

Figure 5. MDM2 expression in the lipoma-like (a), sclerosing (b), and inflammatory variant (c) of well-differentiated liposarcoma/atypical lipomatous tumor.

A lack of MDM2 amplification does not entirely preclude the diagnosis of ALT/WDL. In Li–Fraumeni syndrome, the occurrence of p53+/MDM2− ALT/WDL can be an early expression of the disease [8].

It is of interest that in the past, a well-differentiated spindle cell liposarcoma subtype was described. This group of tumors is now called atypical spindle cell lipoma, since it has a different genetic background, relating it to spindle cell lipoma, with deletion of the Rb-1 gene [9][10].

Very recently, rare cases of “dysplastic lipoma”, “anisometric cell lipoma”, or “minimally ALT” have been reported. These tumors, which do not fit neatly into the category of lipoma or ALT, show prominent variation in adipocyte size, frequent single-cell adipocytic necrosis, limited nuclear enlargement and hyperchromasia, and minimally thickened fibrous septa. These tumors do not show MDM2 amplification as determined by FISH, but are positive for MDM2 RNA-ISH. In addition, they can show deletion of the RB-1 gene on 13q14 [11][12][13]. Clinically, local recurrence in dysplastic lipoma is estimated to be approximately 10%, which is intermediate between lipoma and ALT. Further studies are warranted to clarify the exact classification of these lesions.

3. Low-Grade Osteosarcoma

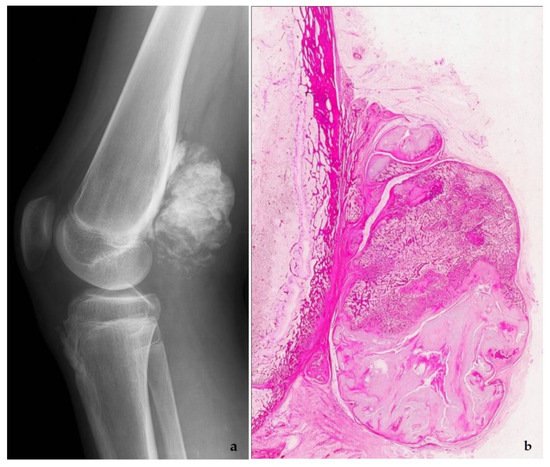

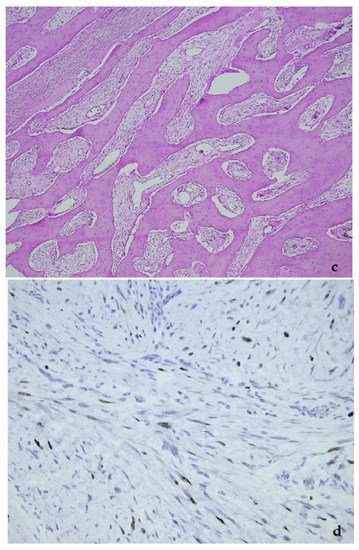

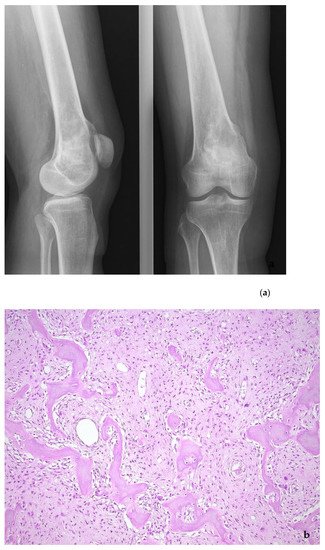

Low-grade osteosarcomas are rare and are subdivided in parosteal and low-grade central osteosarcoma. In both tumors, the diagnosis is often impossible in the absence of imaging features, because they often look deceptively bland. Parosteal osteosarcoma represents 4–5% of all osteosarcomas and is the most frequent surface osteosarcoma. It typically develops on the posterior surface of the distal femur of young adults, mainly in the third decade. The humerus can also be rarely involved. On imaging, a heavily mineralized mass attached to the cortex is seen (Figure 6). Histologically, fascicles of non-atypical spindle cells admixed with parallel bone trabecula are typical (Figure 6). In half of the cases, cartilage islands can be seen, and about half of the tumors transgress the cortex and invade the medullary cavity. Fifteen to 43% dedifferentiate into a high grade (osteo)sarcoma [14]. Low grade central osteosarcoma only accounts for 1–2% of osteosarcomas and is mainly seen in the metaphysis of long bones, tibia and femur being most affected. This tumor rarely involves jaw bones, axial and small tubular bones. Half of the cases occur in the second to third decade. On imaging, a large lytic to mineralized mass is seen, often associated with focal cortical disruption, which can be hard to see (Figure 7). On histology, the tumor consists of a fascicular and moderately cellular fibroblastic proliferation, with minimal or no atypia. The neoplastic bone can present as curved bone trabeculae, mimicking fibrous dysplasia, or as longitudinal seams of bone, as seen in parosteal osteosarcoma (Figure 7). Bone formation can even be absent, resulting in a picture that resembles desmoplastic fibroma or low-grade fibrosarcoma. Very rarely dedifferentiation can occur resulting in a classical high-grade osteosarcoma-like picture [15]. Both tumors harbor long marker or ring chromosomes with amplified 12q13-15 regions, including the MDM2 and CDK4 genes [16][17]. In a high proportion of cases, immunohistochemical MDM2 and/or CDK4 expression can be found as well. In this respect, search for MDM2 amplification/expression can be very useful to distinguish these low-grade sarcomas from their—often benign—mimics (Figure 6 and Figure 7) [18]. The prognosis of both neoplasms is excellent, with 5-year survival rates of 90% upon complete resection. Chemotherapy is only administered in cases of dedifferentiation, when the prognosis is that of a conventional osteosarcoma. Interestingly, when low-grade central or parosteal osteosarcoma dedifferentiate into a high-grade sarcoma, they retain their MDM2/CDK4 amplification and overexpression. In addition, the finding of MDM2 and/or CDK4 amplification/overexpression in a high-grade osteosarcoma indicates progression/dedifferentiation from a low-grade osteosarcoma and practically excludes a primary conventional high-grade osteosarcoma [17].

Figure 6. Parosteal osteosarcoma, typically presenting as a mineralized mass at the back of the distal femur, X-ray (a), and whole mount section (b). At high power, the tumor consists of parallel bone trabeculae and a typical spindle cell proliferation (c). MDM2 expression is present as well (d).

Figure 7. Low-grade central osteosarcoma, showing a lytic lesion the distal femur on X-ray (a). On histology, the tumor strongly mimics fibrous dysplasia, with the very irregular bone trabeculae embedded in e fibrous stroma (b). The amplification of the MDM2 gene supports the diagnosis (c).

References

- Momand, J.; Wu, H.H.; Dasgupta, G. MDM2-master regulator of the p53 tumor suppressosofier protein. Gene 2000, 242, 15–29.

- Cissé, M.Y.; Pyrdziak, S.; Firmin, N.; Gayte, L.; Heuillet, M.; Bellvert, F.; Fuentes Delpech, H.; Riscal, R.; Arena, G.; Chibon, F.; et al. Targeting MDM2-dependent serine metabolism as a therapeutic strategy for liposarcoma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, 1–13.

- Sbaraglia, M.; Dei Tos, A.P.; Pedeutour, F. Atypical lipomatous tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma. In WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Soft Tissue and Bone Tumors; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020; pp. 36–38.

- Weaver, J.; Rao, P.; Goldblum, J.R.; Joyce, M.J.; Turner, S.L.; Lazar, A.J.F.; Lόpez-Terada, D.; Tubbs, R.R.; Rubin, B.P. Can MDM2 analytical tests performed on core needle biopsy be relied upon to diagnose well-differentiated liposarcoma? Mod. Pathol. 2010, 23, 1301–1306.

- Kimura, H.; Dobashi, Y.; Nojima, T.; Nakamura, H.; Yamamoto, N.; Tsuchiya, H.; Ikeda, H.; Sawada-Kitamura, S.; Oyama, T.; Ooi, A. Utility of fluorescence in situ hybridization to detect MDM2 amplification in liposarcomas and their morphological mimics. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2013, 6, 1306–1316.

- Kulkarni, A.S.; Wojcik, J.B.; Chougule, A.; Arora, K.; Chittampalli, Y.; Kurzawa, P.; Mullen, J.T.; Chebib, I.; Nielsen, G.P.; Rivera, N.M.; et al. MDM2 RNA In Situ Hybridization for the Diagnosis of Atypical Lipomatous Tumor, A Study Evaluating DNA, RNA, and Protein Expression. AM J. Surg. Pathol. 2019, 43, 446–454.

- Clay, M.R.; Martinez, A.P.; Weiss, S.W.; Edgar, M.A. MDM2 Amplification in Problematic Lipomatous Tumors. Analysis of FISH Testing Criteria. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2015, 39, 1433–1439.

- Deblenko, L.V.; Perez-Atayde, A.R.; Dubois, S.G.; Grier, H.E.; Pai, S.-Y.; Shamberger, R.C.; Kozakewich, H.P.W. p53+/mdm2- Atypical Lipolatous Tumor/Well-differentiated Lipomasarcoma in Young Children: An Early Expression of Li-Fraumeni Syndrome. Pediatric Dev. Pathol. 2010, 13, 218–224.

- Mentzel, T.; Palmedo, G.; Kuhnen, C. Well-differentiated spindle cell liposarcoma (‘atypical spindle cell lipomatous tumor’) does not belong to the spectrum of atypical lipomatous tumor but has a close relationship to spindle cell lipoma: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of six cases. Mod. Pathol. 2010, 23, 729–736.

- Creytens, D. What’s new in adipocytic neoplasia? Virchows Archiv. 2020, 476, 29–39.

- Hung, Y.P.; Michal, M.; Dubuc, A.M.; Rosenberg, A.E.; Nielsen, G.P. Dysplastic lipoma: potential diagnostic pitfall of using MDM2 RNA in situ hybridization to distinguish between lipoma and atypical lipomatous tumor. Hum. Pthology 2020, 101, 53–57.

- Agaimy, A. Anisometric cel lipoma: Insight from a case series and review of the literature on adipocytic neoplasms in survivors of retinoblastoma suggest a role for RB1 loss and possible relationship to fat-predominant (“fat-only”) spindle cell lipoma. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2017, 29, 52–56.

- den Bakker, M.A. Response to “‘Dysplastic Lipoma’ Is Probably Not a Separate Entity but Rather Belongs to the Morphological Spectrum of Atypical Spindle Cell/Pleomorphic Lipomatous Tumor”. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2020, 28, 931.

- Wang, J.; Nord, K.H.; O’Donnell, P.G.; Yoshida, A. Parosteal osteosarcoma. In WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Soft Tissue and Bone Tumors; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020; pp. 410–413.

- Yoshida, A.; Bredella, M.A.; Gambarotti, M.; Sumathi, V.P. Low-grade central osteosarcoma. In WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Soft Tissue and Bone Tumors; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020; pp. 400–402.

- Dujardin, F.; Bui Nhuyen Binh, M.; Bouvier, C.; Gomez-Brouchet, A.; Larousserie, F.; de Muret, A.; Louis-Brennetot, C.; Aurias, A.; Coindre, J.M.; Guillou, L.; et al. MDM2 and CDK4 immunohistochemistry is a valuable tool in the differential diagnosis of low-grade osteosarcomas and other primary fibro-osseous lesions of the bone. Mod. Pathol. 2011, 24, 624–637.

- Yoshida, A.; Ushiku, T.; Motoi, T.; Beppu, Y.; Fukayama, M.; Tsuda, H.; Shibata, T. MDM2 and CDK4 Immunohistochemical Coexpression in High-grade Osteosarcoma: Correlation with a Dedifferentiated Subtype. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012, 36, 423–431.

- Lott Limbach, A.; Lingen, M.W.; McElherne, J.; Mashek, H.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Hyjek, E.; Mostofi, R.; Cipriani, N.A. The Utility of MDM2 and CDK4 Immunohistochemistry and MDM2 FISH in Craniofacial Osteosarcoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2020, 14, 889–898.

More

Information

Subjects:

Orthopedics

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.4K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

29 Apr 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No