| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Elena Piccinin | + 3372 word(s) | 3372 | 2021-04-21 04:19:48 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 3372 | 2021-04-28 04:53:00 | | |

Video Upload Options

The family of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1 comprises three members, PGC-1α, PGC-1β, and PGC-related coactivator (PRC). PGC-1s act as ‘molecular switches’ in many metabolic pathways, coordinating transcriptional programs involved in the control of cellular metabolism and overall energy homeostasis as well as antioxidant defence.

1. PGC-1 Family: The Masters of Mitochondrial Biogenesis

The family of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1 comprises three members, PGC-1α, PGC-1β, and PGC-related coactivator (PRC). PGC-1s act as ‘molecular switches’ in many metabolic pathways, coordinating transcriptional programs involved in the control of cellular metabolism and overall energy homeostasis as well as antioxidant defence [1]. Their versatile actions are achieved by interacting with different transcription factors and nuclear receptors in a tissue-specific manner.

Notably, in analysing the PGC-1α gene, it has emerged that different variants originating from diverse transcription start sites exist [2]. This has led to the identification of a so-called “brain variant” that is more abundant in the human brain than the canonical isoform [3]. Moreover, an alternative splicing event, which introduces a premature stop codon, yields a shortened version of the coactivator, named NT-PGC-1α that is highly abundant in the mouse brain [4].

1.1. PGC-1s’ Architecture

The modular structure of PGC-1s is highly conserved among all three members of the family. The N-terminus of PGC-1 contains a strong transcriptional activation domain, whereas the C-terminal region holds a serine/arginine rich domain and an RNA binding domain that couples pre-mRNA splicing with transcription [5]. At its N-terminus domain, PGC-1 interacts with several histone acetyltransferase (HAT) complexes, including cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB)-binding protein, p300, and steroid receptor coactivator-1 (SRC-1) [6]. On the other side, in the C-terminal region, other activation complexes dock PGC-1, including the TRAP/DRIP (thyroid receptor-associated protein/vitamin D receptor-interacting protein), also known as Mediator complex, which facilitates direct interaction with the transcription initiation machinery [7], and the SWI/SNF (switch/sucrose non-fermentable) that acts as a chromatin-remodelling complex, through its interaction with BAF60a [8]. This peculiarity of PGC-1s to function as a protein docking platform for the recruitment and assembly of various chromatin remodelling and histone-modifying enzymes, which easily allow the access of the transcription machinery to DNA by altering the local chromatin state, contributes to the remarkably powerful PGC-1s coactivation capacity.

Furthermore, an alternative mechanism to increase gene expression relies on the capability of the PGC-1α transcriptional activator complex to displace repressor proteins, such as histone deacetylase and small heterodimer partner (SHP), on its target promoters [9].

PGC-1α and PGC-1β share a common similar domain in the internal region, which functions as a repression domain [6], and several clusters of conserved amino acids, such as the LXXLL motif that is recognized by nuclear receptors and host cell factor 1 interacting motif [10][11]. Although it contains the same activation domain and RNA-binding domain as the other members of the family, PRC shows poor sequence similarity to PGC-1α and PGC-1β [12]. Few studies have been conducted until now to elucidate the functions of PRC, and to our knowledge, none of them focus primarily on its activity in the brain. Therefore, this member of the PGC-1 family will be not considered in this review.

1.2. PGC-1s’ Activity: Boosting Mitochondrial Functions

Although PGC-1s display an extremely powerful autonomous transcriptional activity, the mechanism through which PGC-1s activate gene expression is to date poorly understood. The spatial and temporal assemblance of the several activation complexes to PGC-1 is still unknown. The major current hypothesis is that PGC-1 binds to a specific transcription factor in the promoter region, followed by the recruitment of P300 and TRAP/DRIP complexes which opens the chromatin through histone acetylation activity, thus allowing the initiation of the transcription via RNA polymerase II (RNApolII). Moreover, the involvement of additional proteins in RNA elongation and processing as part of the PGC-1 complexes suggests that it might move along the elongating RNA and take part in the mRNA maturation. To terminate gene expression, the acetyltransferase GCN5 acetylates PGC-1 at several lysine residues, inducing re-localization of PGC-1 from the promoter region to subnuclear foci where its transcriptional activity is inhibited [13][14]. On the contrary, sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) activates PGC-1 by deacetylating lysine residues, thus inducing the expression of PGC-1 target genes [15].

Another level of complexity is introduced by other post-translational modifications of PGC-1s, such as phosphorylation and methylation, as well as by the interaction with co-repressors which alters PGC-1s stability and activity. PGC-1α could be directly phosphorylated by three different kinases. p38 MAP kinase and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylate PGC-1α, stabilizing the protein and leading to an increase in gene expression activity [16][17][18][19]. Differently, protein kinase B (AKT) produces a more unstable PGC-1α protein, with consequently decreased expression of target genes [20]. Furthermore, PRMT1 (protein arginine N-methyltransferase 1) methylates PGC-1α on three arginine residues in the C-terminus, hence promoting its activation [21].

It is plausible that PGC-1α acts in multiple transcriptional complexes whose composition might depend on the specific target genes as well as on different metabolic signals [22]. Indeed, PGC-1s may interact with different transcription factors, activating diverse biological programs in a tissue-specific manner. PGC-1α was originally described through its functional interaction with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) in brown adipose tissue (BAT), a mitochondria rich tissue, where it regulates adaptive thermogenesis in response to cold [23]. Further studies revealed that the PGC-1s carry out a plethora of biological responses finalized to manage situations of energy shortage. One of the best characterized functions of PGC-1s resides in their ability to promote mitochondrial biogenesis by coactivating different transcription factors, such as the oestrogen-related receptor α (ERRα), the Nuclear Respiratory Factors 1 and 2 (NRF1 and NRF2, respectively), and the transcriptional repressor protein yin yang 1 (YY1) [24][25][26]. These transcription factors, in turn, regulate the expression of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), which plays an essential role in mtDNA replication, maintenance, and transcription [27]. Moreover, both NRF1 and NRF2 guarantee mitochondrial homeostasis by modulating the expression of nuclear genes for components of the OXPHOS system, such as ATP synthase, cytochrome c, and cytochrome c oxidase [28][29]. In addition to the powerful activity as master regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis, PGC-1s positively control the expression of genes involved in antioxidant response [30]. Finally, PGC-1s can also regulate several other metabolic pathways in different tissues, including gluconeogenesis, fatty acid β-oxidation, thermogenesis, and de novo lipogenesis [1]. The gluconeogenic pathway is mainly initiated by PGC-1α, rather than PGC-1β [31]. Particularly, PGC-1α activates gluconeogenesis interacting with forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1), hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF4α), and glucocorticoid receptor (GR) [32][33][34]. The capacity to sustain fatty acid catabolism is particularly evident in the fasted liver, where PGC-1s act as powerful coactivators of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) and promote the synthesis of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation, such as medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT1A) [35][36]. In BAT, PGC-1s are able to drive the production of heat by inducing the expression of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) [37][38]. Finally, PGC-1β alone is able to regulate de novo lipogenesis and very low-density lipoprotein trafficking in the liver, mainly by interacting with liver X receptor (LXR) and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP1c), leading to the expression of fatty acid synthase (FASN) and SCD1 [39][40][41]. It is important to note that in many tissues the functions of PGC-1α and PGC-1β may overlap. However, in some organs like the liver, these two coactivators exert opposite functions, with PGC-1α mainly regulating fatty acid β-oxidation during fasting and PGC-1β activating de novo synthesis of fatty acids after the intake of a meal enriched in lipids [42]. Although still not well investigated, the occurrence of the same phenomenon in other organs cannot be excluded.

2. PGC-1s in Parkinson’s Disease

The association between PD and alteration of mitochondrial homeostasis has been extensively reported. However, only recently has it been highlighted that disruptions of mitochondrial biogenesis and dynamics, rather than mitophagy, are closely associated with the disease onset. This has resulted in a detailed evaluation of the role of PGC-1s on the onset and progression of PD.

The first evidence of the involvement of PGC-1s in neurodegenerative diseases came from two independent studies on whole body PGC-1α knock out (PGC-1αKO) mice [35][43]. Morphologically, the absence of PGC-1α in the brain results in a well-preserved cerebral cortex with the presence of vacuoles in neurons containing aggregates of membranous material [35]. Nevertheless, these mice display behavioural abnormalities peculiar to neurological disorders, indicative of lesions in the striatum [43]. A direct demonstration of the link between PGC-1α and PD was the higher vulnerability of PGC-1αKO mice to the neurodegenerative effects of MPTP and kainic acid, due to the lack of the PGC1α-dependent induction of the antioxidant response [44]. Furthermore, cultured PGC1α-null nigral neurons were more sensitive to the accumulation of the overexpressed human α-synuclein [45] and conditional PGC1α-KO in the substantia nigra of adult mice caused DA neuron loss associated with a marked decline of mitochondrial biogenesis protein markers [46]. Indeed, while the expression of this coactivator protects neuronal cells from ROS-induced cell death via induction of several detoxifying enzymes (superoxide dismutase 2, SOD2; glutathione peroxidase 1, GPX1), its ablation results in the accumulation of nitrotyrosylated proteins and loss of DA neurons [44]. Furthermore, transgenic mice in which the expression of the PGC-1s target gene TFAM has been disrupted display lower mtDNA expression and respiratory chain deficiency that result in the adult onset of Parkinsonism [47]. All these insights provide the impetus to deepen the knowledge of PGC-1s in PD.

Despite PGC-1α and PGC-1β are both powerful coactivators of mitochondrial biogenesis and antioxidant response, PGC-1α has been far more investigated as compared to PGC-1β, especially in the context of PD. Although PGC-1α and PGC-1β control mitochondrial capacity in an additive and independent manner in different subtypes of neurons, the overexpression of PGC-1α significantly reduces the PGC-1β level [45][48]. Furthermore, while PGC-1α can compensate PGC-1β loss and restore the induction of antioxidant genes, PGC-1β fails to cope with the absence of PGC-1α, being only slightly induced in PGC-1α null mice [44][45]. However, since in other tissues PGC-1β is able to drive genes involved in de novo lipogenesis, including SCD1 [39][40], and given that SCD1 expression has proved to be deleterious for PD, it would be intriguing to evaluate if PGC-1β retains this ability also in DA neurons and whether the activation of this pathway may have detrimental effects.

2.1. Deepening the Role of PGC-1α in Parkinson’s Disease

Numerous studies have been carried out to fully elucidate the role played by PGC-1α in PD. A comparative analysis of a large cohort of PD patients and age-matched controls has revealed that two PGC-1α variants are associated with the risk of PD onset (rs6821591 CC and rs2970848 GG) [49]. Further studies have led to the identification of different PGC-1α isoforms in the brain, including a truncated 17 kDa protein that lacks the LXXLL site of interaction with several transcription factors [46][50]. This 17 kDa isoform has been found upregulated in the substantia nigra of PD patients, where it inhibits the coactivation of several transcription factors by the full-length PGC-1α [50]. The selective knockout of different PGC-1α isoforms in mice may lead to a decrease of dopamine content in the striatum and to an associated loss of DA neurons [46]. Accordingly, in human PD tissues, the levels of PGC-1α and of mitochondrial markers are reduced compared to control patients and are negatively correlated with the severity of the disease [46][51][52][53][54][55]. Conversely, primary fibroblasts from PD patients display upregulation of PGC-1α, even if its target genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and fatty acid β-oxidation processes are unchanged or downregulated and mitochondria display significant morphometric changes [56][57]. This may suggest that a post-translational mechanism may also occur, thus jeopardizing the elevated quantity of the coactivator and interfering with its activity.

The low expression of PGC-1α observed in the PD brain is probably due to the high level of gene methylation that has been found in PD patients [53]. Dense DNA methylation is usually associated with gene repression, and the PGC-1α promoter is proximal to a non-canonical cytosine methylation site that is epigenetically modified in the brain of sporadic PD patients [51]. Notably, free fatty acids can induce the hypermethylation of the PGC-1α promoter. The administration of palmitate to cortical neurons in vitro and to a mouse model of PD in vivo causes promoter hypermethylation, thus lowering the level of PGC-1α and mitochondria-associated genes as well as the concomitant induction of pro-inflammatory genes [51]. Curiously, both a population-based case-control study and a prospective study indicate that a higher caloric intake, due to elevated consumption of animal-derived saturated fatty acids, tends to be associated with a greater risk of PD [58][59]. Moreover, rats subjected to high-fat diet feeding and to infusion of 6-hydroxydopamine displayed DA neurons depletion in the striatum, despite the absence of differences in locomotor activity [60]. Altogether this suggests that a high dietary introit of fatty acids, especially saturated ones, may repress the expression of PGC-1α and related mitochondrial genes, thus lowering the threshold for developing PD.

Studies performed in Drosophila melanogaster further corroborate the association between disrupted PGC-1α functions and PD onset. To some extent, the high degree of conservation between PGC-1α and its D. melanogaster homolog Spargel and the lack of gene redundancy make this organism an ideal model system to determine the role of PGC-1α in PD. The inhibition of Spargel via RNAi in DA neurons causes an altered climbing activity, with an unexpected increase of mean lifespan probably ascribable to the mitochondrial unfolded protein response and/or a ROS-dependent mitohormesis [61]. Further studies have demonstrated that silencing Spargel in flies increases the PD related phenotypes, including climbing defects, decreased mitochondrial mass, and lower dopamine levels [62]. However, the genetic or pharmacological activation of Spargel is sufficient to rescue the disease phenotype [62].

Coherently, PGC-1α null mice display abnormal mitochondria in neurons and are more prone to oxidative stress that may be eventually related to neurodegeneration. Nonetheless, re-expression of PGC-1α in these mice restores mitochondrial functions and oxidative stress detoxification [45].

The overexpression of PGC-1α in several in vitro and in vivo models results in an overall protection against neurodegeneration. Treatment of the SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma human cell line with the neurotoxin N-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium leads to serious mitochondrial damage that can be functionally reversed by the overexpression of PGC-1α [63]. Moreover, resveratrol treatment in Parkin-mutated fibroblasts promotes PGC-1α activity via SIRT-1, thus resulting in increased mitochondrial biogenesis together with lower ROS accumulation that together ameliorate the phenotypic impact of the mitochondrial dysfunctions caused by the Parkin mutation [64]. Accordingly, transgenic mice overexpressing PGC-1α in MPTP-treated DA neurons display induction of the antioxidant genes Sod2 and thioredoxin 2 (Trx2) as well as increased OXPHOS, which collectively promote neuronal viability and prevent striatal dopamine loss [65]. Conversely, the adenovirus-mediated overexpression of PGC-1α in the substantia nigra of mice increases their susceptibility to MPTP, as indicated by the loss of DA neurons [66]. This deleterious effect may be ascribable to the high level of PGC-1α activity caused by the viral vector microinjection and may shed light on the importance of a balanced regulation of this coactivator to achieve beneficial effects.

2.2. PGC-1α and Parkinson’s Mutated Genes: Defining The Network Implicated in Parkinson’s Disease

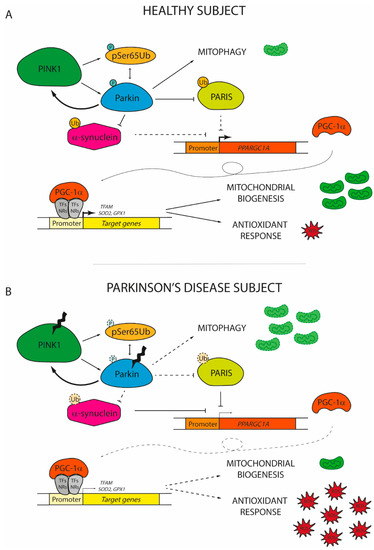

Besides the roles of PGC-1α in different PD scenarios based on its capacity to boost mitochondrial biogenesis and the antioxidant response discussed above, it is now clear that PGC-1α protects against neurodegeneration as a player of a more intricated mechanism whose failure may drive the onset and progression of PD (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 (PGC-1α) in the onset of Parkinson’s disease. (A) In healthy subjects, damaged mitochondria are promptly replaced with new functional organelles. Mitochondrial depolarization induces PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) to phosphorylate serine 65 residue of ubiquitin (pSer65Ub) and of Parkin, which in turn interact together to increase the PINK1 phosphorylation rate of Parkin. The activation of the PINK1/Parkin pathway promotes the degradation of dysfunctional mitochondria via mitophagy and concomitantly induces the expression of PGC-1α by the ubiquitination of PARIS and α-synuclein. By coactivating nuclear receptors (NRs) or transcription factors (TFs), PGC-1α promotes the expression of genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis (mitochondrial transcription factor A, TFAM) and antioxidant response (superoxide dismutase 2, SOD2; glutathione peroxidase 1, GPX1). (B) In Parkinson’s disease individuals, PINK1 and Parkin usually display loss-of-function mutations. Therefore, the PINK1/Parkin axis cannot prevent the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria due to its inability to sustain mitophagy. At the same time, altered Parkin fails to promote the degradation of both PARIS and α-synuclein, which start to accumulate in the nucleus inhibiting PGC-1α transcription. The low levels of PGC-1α observed in PD patients are not sufficient to induce the expression of genes involved in the renewal of mitochondria and in the antioxidant response. Thereby, reactive oxygen species (ROS) start to accumulate, finally leading to the damage and the death of dopaminergic neurons. Dashed lines and soft colours represent inhibited actions/pathways.

The expression of PGC-1α is finely regulated by PARIS, a KRAB and zinc finger protein that accumulates in the human PD brain [67]. PARIS acts as a physiological transcriptional repressor of PGC-1α, downregulating the coactivator and its target genes, [67]. Generally, the amount of PARIS is tightly controlled by the PINK1/Parkin axis, which mediates PARIS degradation via ubiquitination [68]. However, modifications to either PINK1 or Parkin that alter this regulatory pathway allow PARIS to accumulate inside the neurons [69][70][71]. The overexpression of PARIS negatively affects mitochondrial biogenesis causing progressive DA neuron degeneration and loss [70]. In flies, the ubiquitous expression of PARIS results in shortened lifespan and climbing defects that are promptly reversed by PINK1, Parkin, or PGC-1α overexpression [70]. Noteworthy, the loss-of-function of Parkin in mice and in human-derived cells leads to mitochondrial respiratory function decline coupled with a decrease of mitochondrial mass and of the antioxidant response, a phenotype that closely reminds those of PARIS-overexpressing cells [69][71]. Accordingly, the reduction of PARIS level in Parkin knockout cells and mice is sufficient to restore mitochondrial biogenesis and cellular respiration [69][71]. By contrast, the effect of Parkin on mitochondrial density is abolished in PGC-1α null cortical neurons in vitro and the synergic action on mitochondrial functions given by the co-expression of both Parkin and PGC-1α provides significant neuroprotection [72]. This indicates that Parkin is fundamental to ensure the proper action of PGC-1α to stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis, by shutting down PARIS.

PINK1/Parkin axis plays a double role in controlling both the genesis and the destruction of mitochondria. Therefore, it is easy to wonder how the PGC-1α action is finely tuned to keep mitochondrial homeostasis and if the activation of mitophagy in response to damage can start a signal that activates PGC-1α in order to restore the mitochondrial pool. Although this is still an open question, it is clear that the rescue of mitophagy in Parkin knockout mice does not increase PGC-1α expression and activity [69]. However, PGC-1α regulates the abundance of mitofusin2 (Mfn2), a protein with a central role in mitochondrial fusion, whose loss in nigrostriatal DA neurons in mice leads to a neurodegenerative phenotype [72][73]. Once more, this observation provides clues for the existence of a precise regulatory loop that underlies mitochondrial homeostasis through PGC-1α.

Although no direct interaction has been observed between PGC-1α and DJ-1, since DJ-1 can compensate for PINK1 loss, it will be intriguing to evaluate if PGC-1α functions can be rescued by DJ-1 expression in PD cells in terms of mitochondrial biogenesis and antioxidant response [74][75].

In addition to PINK1 and Parkin, several studies have demonstrated a strong interference with other genes frequently mutated in PD. One of them is α-synuclein, whose overexpression and oligomerization negatively correlates with PGC-1α level in the human PD brain as well as in murine and cell culture models of α-synuclein oligomerization [54]. Particularly, under oxidative stress, α-synuclein may localize in the nucleus where it specifically binds to the PGC-1α promoter, decreasing its activity. By reducing the expression of the coactivator and related target genes, α-synuclein impairs the mitochondrial functions [76]. Intriguingly, the ablation of PGC-1α renders both mice and human neurons more prone to α-synuclein accumulation and toxicity [45][77]. By contrast, the pharmacological activation or genetic overexpression of PGC-1α reduces α-synuclein oligomerization and attenuates neurotoxicity in vitro [54][76]. The reciprocal influence of PGC-1α and α-synuclein generates a vicious cycle that may play an important role in the disease progression. Since α-synuclein can be ubiquitinated by Parkin [78][79], it would also be interesting to understand how the different actors involved in PD pathogenesis may act in concert to protect from neurodegeneration and neuronal loss.

References

- Villena, J.A. New insights into PGC-1 coactivators: Redefining their role in the regulation of mitochondrial function and beyond. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 647–672.

- Yoshioka, T.; Inagaki, K.; Noguchi, T.; Sakai, M.; Ogawa, W.; Hosooka, T.; Iguchi, H.; Watanabe, E.; Matsuki, Y.; Hiramatsu, R.; et al. Identification and characterization of an alternative promoter of the human PGC-1alpha gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 381, 537–543.

- Soyal, S.M.; Felder, T.K.; Auer, S.; Hahne, P.; Oberkofler, H.; Witting, A.; Paulmichl, M.; Landwehrmeyer, G.B.; Weydt, P.; Patsch, W.; et al. A greatly extended PPARGC1A genomic locus encodes several new brain-specific isoforms and influences Huntington disease age of onset. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 3461–3473.

- Zhang, Y.; Huypens, P.; Adamson, A.W.; Chang, J.S.; Henagan, T.M.; Boudreau, A.; Lenard, N.R.; Burk, D.; Klein, J.; Perwitz, N.; et al. Alternative mRNA splicing produces a novel biologically active short isoform of PGC-1alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 32813–32826.

- Monsalve, M.; Wu, Z.; Adelmant, G.; Puigserver, P.; Fan, M.; Spiegelman, B.M. Direct coupling of transcription and mRNA processing through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Mol.Cell 2000, 6, 307–316.

- Puigserver, P.; Adelmant, G.; Wu, Z.; Fan, M.; Xu, J.; O’Malley, B.; Spiegelman, B.M. Activation of PPARgamma coactivator-1 through transcription factor docking. Science 1999, 286, 1368–1371.

- Wallberg, A.E.; Yamamura, S.; Malik, S.; Spiegelman, B.M.; Roeder, R.G. Coordination of p300-mediated chromatin remodeling and TRAP/mediator function through coactivator PGC-1alpha. Mol. Cell 2003, 12, 1137–1149.

- Li, S.; Liu, C.; Li, N.; Hao, T.; Han, T.; Hill, D.E.; Vidal, M.; Lin, J.D. Genome-wide coactivation analysis of PGC-1alpha identifies BAF60a as a regulator of hepatic lipid metabolism. Cell Metab. 2008, 8, 105–117.

- Borgius, L.J.; Steffensen, K.R.; Gustafsson, J.A.; Treuter, E. Glucocorticoid signaling is perturbed by the atypical orphan receptor and corepressor SHP. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 49761–49766.

- Lin, J.; Wu, H.; Tarr, P.T.; Zhang, C.Y.; Wu, Z.; Boss, O.; Michael, L.F.; Puigserver, P.; Isotani, E.; Olson, E.N.; et al. Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1 alpha drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres. Nature 2002, 418, 797–801.

- Kressler, D.; Schreiber, S.N.; Knutti, D.; Kralli, A. The PGC-1-related protein PERC is a selective coactivator of estrogen receptor alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 13918–13925.

- Andersson, U.; Scarpulla, R.C. Pgc-1-related coactivator, a novel, serum-inducible coactivator of nuclear respiratory factor 1-dependent transcription in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 21, 3738–3749.

- Lerin, C.; Rodgers, J.T.; Kalume, D.E.; Kim, S.H.; Pandey, A.; Puigserver, P. GCN5 acetyltransferase complex controls glucose metabolism through transcriptional repression of PGC-1alpha. Cell Metab. 2006, 3, 429–438.

- Kelly, T.J.; Lerin, C.; Haas, W.; Gygi, S.P.; Puigserver, P. GCN5-mediated transcriptional control of the metabolic coactivator PGC-1beta through lysine acetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 19945–19952.

- Rodgers, J.T.; Lerin, C.; Haas, W.; Gygi, S.P.; Spiegelman, B.M.; Puigserver, P. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1alpha and SIRT1. Nature 2005, 434, 113–118.

- Puigserver, P.; Rhee, J.; Lin, J.; Wu, Z.; Yoon, J.C.; Zhang, C.Y.; Krauss, S.; Mootha, V.K.; Lowell, B.B.; Spiegelman, B.M. Cytokine stimulation of energy expenditure through p38 MAP kinase activation of PPARgamma coactivator-1. Mol. Cell 2001, 8, 971–982.

- Liang, H.L.; Dhar, S.S.; Wong-Riley, M.T. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and calcium channels mediate signaling in depolarization-induced activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha in neurons. J. Neurosci. Res. 2010, 88, 640–649.

- Irrcher, I.; Ljubicic, V.; Kirwan, A.F.; Hood, D.A. AMP-activated protein kinase-regulated activation of the PGC-1alpha promoter in skeletal muscle cells. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3614.

- Jager, S.; Handschin, C.; St-Pierre, J.; Spiegelman, B.M. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 12017–12022.

- Li, X.; Monks, B.; Ge, Q.; Birnbaum, M.J. Akt/PKB regulates hepatic metabolism by directly inhibiting PGC-1alpha transcription coactivator. Nature 2007, 447, 1012–1016.

- Teyssier, C.; Ma, H.; Emter, R.; Kralli, A.; Stallcup, M.R. Activation of nuclear receptor coactivator PGC-1alpha by arginine methylation. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 1466–1473.

- Rodgers, J.T.; Lerin, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Puigserver, P. Metabolic adaptations through the PGC-1 alpha and SIRT1 pathways. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 46–53.

- Puigserver, P.; Wu, Z.; Park, C.W.; Graves, R.; Wright, M.; Spiegelman, B.M. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell 1998, 92, 829–839.

- Wu, Z.; Puigserver, P.; Andersson, U.; Zhang, C.; Adelmant, G.; Mootha, V.; Troy, A.; Cinti, S.; Lowell, B.; Scarpulla, R.C.; et al. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell 1999, 98, 115–124.

- Schreiber, S.N.; Emter, R.; Hock, M.B.; Knutti, D.; Cardenas, J.; Podvinec, M.; Oakeley, E.J.; Kralli, A. The estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRalpha) functions in PPARgamma coactivator 1alpha (PGC-1alpha)-induced mitochondrial biogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 6472–6477.

- Scarpulla, R.C. Nuclear control of respiratory chain expression by nuclear respiratory factors and PGC-1-related coactivator. Ann. N. Y. Acad Sci. 2008, 1147, 321–334.

- Larsson, N.G.; Wang, J.; Wilhelmsson, H.; Oldfors, A.; Rustin, P.; Lewandoski, M.; Barsh, G.S.; Clayton, D.A. Mitochondrial transcription factor A is necessary for mtDNA maintenance and embryogenesis in mice. Nat. Genet. 1998, 18, 231–236.

- Scarpulla, R.C. Nuclear activators and coactivators in mammalian mitochondrial biogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1576, 1–14.

- Scarpulla, R.C. Transcriptional activators and coactivators in the nuclear control of mitochondrial function in mammalian cells. Gene 2002, 286, 81–89.

- Aquilano, K.; Baldelli, S.; Pagliei, B.; Cannata, S.M.; Rotilio, G.; Ciriolo, M.R. p53 orchestrates the PGC-1alpha-mediated antioxidant response upon mild redox and metabolic imbalance. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 386–399.

- Lin, J.; Tarr, P.T.; Yang, R.; Rhee, J.; Puigserver, P.; Newgard, C.B.; Spiegelman, B.M. PGC-1beta in the regulation of hepatic glucose and energy metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 30843–30848.

- Puigserver, P.; Rhee, J.; Donovan, J.; Walkey, C.J.; Yoon, J.C.; Oriente, F.; Kitamura, Y.; Altomonte, J.; Dong, H.; Accili, D.; et al. Insulin-regulated hepatic gluconeogenesis through FOXO1-PGC-1alpha interaction. Nature 2003, 423, 550–555.

- Herzig, S.; Long, F.; Jhala, U.S.; Hedrick, S.; Quinn, R.; Bauer, A.; Rudolph, D.; Schutz, G.; Yoon, C.; Puigserver, P.; et al. CREB regulates hepatic gluconeogenesis through the coactivator PGC-1. Nature 2001, 413, 179–183.

- Rhee, J.; Inoue, Y.; Yoon, J.C.; Puigserver, P.; Fan, M.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Spiegelman, B.M. Regulation of hepatic fasting response by PPARgamma coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1): Requirement for hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha in gluconeogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 4012–4017.

- Leone, T.C.; Lehman, J.J.; Finck, B.N.; Schaeffer, P.J.; Wende, A.R.; Boudina, S.; Courtois, M.; Wozniak, D.F.; Sambandam, N.; Bernal-Mizrachi, C.; et al. PGC-1alpha deficiency causes multi-system energy metabolic derangements: Muscle dysfunction, abnormal weight control and hepatic steatosis. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e101.

- Koo, S.H.; Satoh, H.; Herzig, S.; Lee, C.H.; Hedrick, S.; Kulkarni, R.; Evans, R.M.; Olefsky, J.; Montminy, M. PGC-1 promotes insulin resistance in liver through PPAR-alpha-dependent induction of TRB-3. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 530–534.

- Sonoda, J.; Mehl, I.R.; Chong, L.W.; Nofsinger, R.R.; Evans, R.M. PGC-1beta controls mitochondrial metabolism to modulate circadian activity, adaptive thermogenesis, and hepatic steatosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 5223–5228.

- Uldry, M.; Yang, W.; St-Pierre, J.; Lin, J.; Seale, P.; Spiegelman, B.M. Complementary action of the PGC-1 coactivators in mitochondrial biogenesis and brown fat differentiation. Cell Metab. 2006, 3, 333–341.

- Lin, J.; Yang, R.; Tarr, P.T.; Wu, P.H.; Handschin, C.; Li, S.; Yang, W.; Pei, L.; Uldry, M.; Tontonoz, P.; et al. Hyperlipidemic effects of dietary saturated fats mediated through PGC-1beta coactivation of SREBP. Cell 2005, 120, 261–273.

- Piccinin, E.; Peres, C.; Bellafante, E.; Ducheix, S.; Pinto, C.; Villani, G.; Moschetta, A. Hepatic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1beta drives mitochondrial and anabolic signatures that contribute to hepatocellular carcinoma progression in mice. Hepatology 2018, 67, 884–898.

- Bellafante, E.; Murzilli, S.; Salvatore, L.; Latorre, D.; Villani, G.; Moschetta, A. Hepatic-specific activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1beta protects against steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2013, 57, 1343–1356.

- Piccinin, E.; Villani, G.; Moschetta, A. Metabolic aspects in NAFLD, NASH and hepatocellular carcinoma: The role of PGC1 coactivators. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 160–174.

- Lin, J.; Wu, P.H.; Tarr, P.T.; Lindenberg, K.S.; St-Pierre, J.; Zhang, C.Y.; Mootha, V.K.; Jager, S.; Vianna, C.R.; Reznick, R.M.; et al. Defects in adaptive energy metabolism with CNS-linked hyperactivity in PGC-1alpha null mice. Cell 2004, 119, 121–135.

- St-Pierre, J.; Drori, S.; Uldry, M.; Silvaggi, J.M.; Rhee, J.; Jager, S.; Handschin, C.; Zheng, K.; Lin, J.; Yang, W.; et al. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell 2006, 127, 397–408.

- Ciron, C.; Zheng, L.; Bobela, W.; Knott, G.W.; Leone, T.C.; Kelly, D.P.; Schneider, B.L. PGC-1alpha activity in nigral dopamine neurons determines vulnerability to alpha-synuclein. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2015, 3, 16.

- Jiang, H.; Kang, S.U.; Zhang, S.; Karuppagounder, S.; Xu, J.; Lee, Y.K.; Kang, B.G.; Lee, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pletnikova, O.; et al. Adult Conditional Knockout of PGC-1alpha Leads to Loss of Dopamine Neurons. eNeuro 2016, 3.

- Ekstrand, M.I.; Terzioglu, M.; Galter, D.; Zhu, S.; Hofstetter, C.; Lindqvist, E.; Thams, S.; Bergstrand, A.; Hansson, F.S.; Trifunovic, A.; et al. Progressive parkinsonism in mice with respiratory-chain-deficient dopamine neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 1325–1330.

- Wareski, P.; Vaarmann, A.; Choubey, V.; Safiulina, D.; Liiv, J.; Kuum, M.; Kaasik, A. PGC-1 and PGC-1 regulate mitochondrial density in neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 21379–21385.

- Clark, J.; Reddy, S.; Zheng, K.; Betensky, R.A.; Simon, D.K. Association of PGC-1alpha polymorphisms with age of onset and risk of Parkinson’s disease. BMC Med Genet. 2011, 12, 69.

- Soyal, S.M.; Zara, G.; Ferger, B.; Felder, T.K.; Kwik, M.; Nofziger, C.; Dossena, S.; Schwienbacher, C.; Hicks, A.A.; Pramstaller, P.P.; et al. The PPARGC1A locus and CNS-specific PGC-1alpha isoforms are associated with Parkinson’s Disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 121, 34–46.

- Su, X.; Chu, Y.; Kordower, J.H.; Li, B.; Cao, H.; Huang, L.; Nishida, M.; Song, L.; Wang, D.; Federoff, H.J. PGC-1alpha Promoter Methylation in Parkinson’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134087.

- Yang, X.D.; Qian, Y.W.; Xu, S.Q.; Wan, D.Y.; Sun, F.H.; Chen, S.D.; Xiao, Q. Expression of the gene coading for PGC-1alpha in peripheral blood leukocytes and related gene variants in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism. Relat. Disord. 2018, 51, 30–35.

- Yang, X.; Xu, S.; Qian, Y.; He, X.; Chen, S.; Xiao, Q. Hypermethylation of the Gene Coding for PGC-1alpha in Peripheral Blood Leukocytes of Patients With Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 97.

- Eschbach, J.; von Einem, B.; Muller, K.; Bayer, H.; Scheffold, A.; Morrison, B.E.; Rudolph, K.L.; Thal, D.R.; Witting, A.; Weydt, P.; et al. Mutual exacerbation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1alpha deregulation and alpha-synuclein oligomerization. Ann. Neurol. 2015, 77, 15–32.

- Zheng, B.; Liao, Z.; Locascio, J.J.; Lesniak, K.A.; Roderick, S.S.; Watt, M.L.; Eklund, A.C.; Zhang-James, Y.; Kim, P.D.; Hauser, M.A.; et al. PGC-1alpha, a potential therapeutic target for early intervention in Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010, 2, 52ra73.

- Pacelli, C.; De Rasmo, D.; Signorile, A.; Grattagliano, I.; di Tullio, G.; D’Orazio, A.; Nico, B.; Comi, G.P.; Ronchi, D.; Ferranini, E.; et al. Mitochondrial defect and PGC-1alpha dysfunction in parkin-associated familial Parkinson’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1812, 1041–1053.

- Antony, P.M.A.; Kondratyeva, O.; Mommaerts, K.; Ostaszewski, M.; Sokolowska, K.; Baumuratov, A.S.; Longhino, L.; Poulain, J.F.; Grossmann, D.; Balling, R.; et al. Fibroblast mitochondria in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease display morphological changes and enhanced resistance to depolarization. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1569.

- Logroscino, G.; Marder, K.; Cote, L.; Tang, M.X.; Shea, S.; Mayeux, R. Dietary lipids and antioxidants in Parkinson’s disease: A population-based, case-control study. Ann. Neurol. 1996, 39, 89–94.

- Chen, H.; Zhang, S.M.; Hernan, M.A.; Willett, W.C.; Ascherio, A. Dietary intakes of fat and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 157, 1007–1014.

- Morris, J.K.; Bomhoff, G.L.; Stanford, J.A.; Geiger, P.C. Neurodegeneration in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease is exacerbated by a high-fat diet. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2010, 299, R1082–R1090.

- Merzetti, E.M.; Staveley, B.E. spargel, the PGC-1alpha homologue, in models of Parkinson disease in Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Neurosci. 2015, 16, 70.

- Ng, C.H.; Basil, A.H.; Hang, L.; Tan, R.; Goh, K.L.; O’Neill, S.; Zhang, X.; Yu, F.; Lim, K.L. Genetic or pharmacological activation of the Drosophila PGC-1alpha ortholog spargel rescues the disease phenotypes of genetic models of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2017, 55, 33–37.

- Ye, Q.; Huang, W.; Li, D.; Si, E.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Chen, X. Overexpression of PGC-1alpha Influences Mitochondrial Signal Transduction of Dopaminergic Neurons. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 3756–3770.

- Ferretta, A.; Gaballo, A.; Tanzarella, P.; Piccoli, C.; Capitanio, N.; Nico, B.; Annese, T.; Di Paola, M.; Dell’aquila, C.; De Mari, M.; et al. Effect of resveratrol on mitochondrial function: Implications in parkin-associated familiar Parkinson’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 902–915.

- Mudo, G.; Makela, J.; Di Liberto, V.; Tselykh, T.V.; Olivieri, M.; Piepponen, P.; Eriksson, O.; Malkia, A.; Bonomo, A.; Kairisalo, M.; et al. Transgenic expression and activation of PGC-1alpha protect dopaminergic neurons in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012, 69, 1153–1165.

- Clark, J.; Silvaggi, J.M.; Kiselak, T.; Zheng, K.; Clore, E.L.; Dai, Y.; Bass, C.E.; Simon, D.K. Pgc-1alpha overexpression downregulates Pitx3 and increases susceptibility to MPTP toxicity associated with decreased Bdnf. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48925.

- Shin, J.H.; Ko, H.S.; Kang, H.; Lee, Y.; Lee, Y.I.; Pletinkova, O.; Troconso, J.C.; Dawson, V.L.; Dawson, T.M. PARIS (ZNF746) repression of PGC-1alpha contributes to neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Cell 2011, 144, 689–702.

- Lee, Y.; Stevens, D.A.; Kang, S.U.; Jiang, H.; Lee, Y.I.; Ko, H.S.; Scarffe, L.A.; Umanah, G.E.; Kang, H.; Ham, S.; et al. PINK1 Primes Parkin-Mediated Ubiquitination of PARIS in Dopaminergic Neuronal Survival. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 918–932.

- Kumar, M.; Acevedo-Cintron, J.; Jhaldiyal, A.; Wang, H.; Andrabi, S.A.; Eacker, S.; Karuppagounder, S.S.; Brahmachari, S.; Chen, R.; Kim, H.; et al. Defects in Mitochondrial Biogenesis Drive Mitochondrial Alterations in PARKIN-Deficient Human Dopamine Neurons. Stem Cell Rep. 2020, 15, 629–645.

- Pirooznia, S.K.; Yuan, C.; Khan, M.R.; Karuppagounder, S.S.; Wang, L.; Xiong, Y.; Kang, S.U.; Lee, Y.; Dawson, V.L.; Dawson, T.M. PARIS induced defects in mitochondrial biogenesis drive dopamine neuron loss under conditions of parkin or PINK1 deficiency. Mol. Neurodegener. 2020, 15, 17.

- Stevens, D.A.; Lee, Y.; Kang, H.C.; Lee, B.D.; Lee, Y.I.; Bower, A.; Jiang, H.; Kang, S.U.; Andrabi, S.A.; Dawson, V.L.; et al. Parkin loss leads to PARIS-dependent declines in mitochondrial mass and respiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 11696–11701.

- Zheng, L.; Bernard-Marissal, N.; Moullan, N.; D’Amico, D.; Auwerx, J.; Moore, D.J.; Knott, G.; Aebischer, P.; Schneider, B.L. Parkin functionally interacts with PGC-1alpha to preserve mitochondria and protect dopaminergic neurons. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 582–598.

- Lee, S.; Sterky, F.H.; Mourier, A.; Terzioglu, M.; Cullheim, S.; Olson, L.; Larsson, N.G. Mitofusin 2 is necessary for striatal axonal projections of midbrain dopamine neurons. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 4827–4835.

- Hao, L.Y.; Giasson, B.I.; Bonini, N.M. DJ-1 is critical for mitochondrial function and rescues PINK1 loss of function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9747–9752.

- Zhong, N.; Xu, J. Synergistic activation of the human MnSOD promoter by DJ-1 and PGC-1alpha: Regulation by SUMOylation and oxidation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008, 17, 3357–3367.

- Siddiqui, A.; Chinta, S.J.; Mallajosyula, J.K.; Rajagopolan, S.; Hanson, I.; Rane, A.; Melov, S.; Andersen, J.K. Selective binding of nuclear alpha-synuclein to the PGC1alpha promoter under conditions of oxidative stress may contribute to losses in mitochondrial function: Implications for Parkinson’s disease. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 993–1003.

- Ebrahim, A.S.; Ko, L.W.; Yen, S.H. Reduced expression of peroxisome-proliferator activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha enhances alpha-synuclein oligomerization and down regulates AKT/GSK3beta signaling pathway in human neuronal cells that inducibly express alpha-synuclein. Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 473, 120–125.

- Shimura, H.; Schlossmacher, M.G.; Hattori, N.; Frosch, M.P.; Trockenbacher, A.; Schneider, R.; Mizuno, Y.; Kosik, K.S.; Selkoe, D.J. Ubiquitination of a new form of alpha-synuclein by parkin from human brain: Implications for Parkinson’s disease. Science 2001, 293, 263–269.

- Norris, K.L.; Hao, R.; Chen, L.F.; Lai, C.H.; Kapur, M.; Shaughnessy, P.J.; Chou, D.; Yan, J.; Taylor, J.P.; Engelender, S.; et al. Convergence of Parkin, PINK1, and alpha-Synuclein on Stress-induced Mitochondrial Morphological Remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 13862–13874.