| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marcella Barbarino | + 5061 word(s) | 5061 | 2021-04-19 10:41:27 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 5061 | 2021-04-27 11:07:39 | | |

Video Upload Options

Malignant mesothelioma is an aggressive cancer of the membranes covering the lung and chest cavity (pleura) or the abdomen (peritoneum), mainly linked to asbestos exposure. Asbestos is a proven human carcinogen but its use is far from being universally banned and the forecasts on the incidence of mesothelioma over the next several years are far from optimistic. Carbon nanotubes are a promising type of nano-materials used in the field of nanotechnology for a wide range of applications. However, the similarities between asbestos and CNTs have raised many concerns about their danger and are still the subject of intense research.

1. Introduction

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is an aggressive cancer of the pleural membranes covering the lungs and is strongly linked to asbestos exposure. MPM generally manifests in an advanced stage after a latency period of 30–40 years following asbestos exposure.

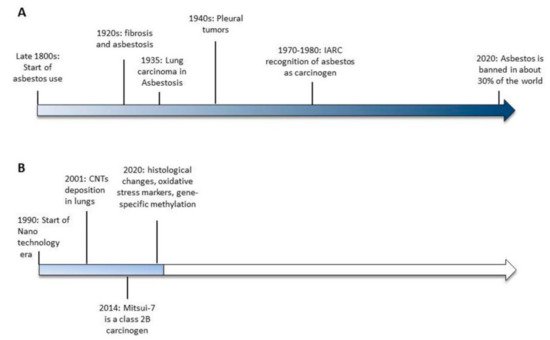

Asbestos is a commercial term describing a group of specific silicate minerals forming bundles of long and thin mineral fibers that, because of their intrinsic characteristic of durability and resistance to chemicals, heat and electricity, were widely used in the late 1800s with the start of the Industrial Revolution. However, as early as 1898, lung damage was described in industry workers exposed to asbestos dust [1] and in the early 1900s, the first reports documenting fibrosis [2][3] and asbestosis [4] in asbestos-exposed workers were published. Only 30 years later (1935), the first association between asbestos and lung cancer was described [5][6] and it was another 10 years passed before asbestos exposure was correlated with pleural tumors, in the work of Wedler in 1943 [7] and the doctorate thesis of Wyres in 1946 [8]. In 1977 [9] and 1987 [10], the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) concluded that asbestos is a human carcinogen and that the size and shape of the fibers influence the incidence of tumors. In 2006 [11] and 2009 [12] asbestos exposure was also correlated with an increased risk of other cancers, such as laryngeal and ovarian cancer.

Currently, even though asbestos is a known carcinogen, it is not banned in about 70% of the world (Figure 1). As such, more than 100 years after the recognition of asbestos as a carcinogenic agent, the case is not yet closed (http://ibasecretariat.org/chron_ban_list.php, accessed on 2nd of October 2020). Indeed, it is important to note that countries that banned asbestos a quarter of a century ago are still contributing to the worldwide toll of more than 100,000 asbestos-related deaths per year [13]. As highlighted by Terracini [13], while banning asbestos is important, that alone does not create an asbestos-free environment. It will take a very long time to ban the use of asbestos worldwide, and it will take an even longer time to end up with an environment that is completely safe from the toxic effects of asbestos. For all of these reasons, the forecasts on the incidence of mesothelioma over the next several years are far from optimistic.

Figure 1. Timelines of the significant events leading to asbestos banning (A) and the available evidences of carbon nanotubes-induced toxicity (B).

It should also be considered that asbestos present in old constructions still represents a daily hazard to human health. There are numerous cases in which the presence of asbestos has been detected during the renovation or demolition of old buildings. The 9/11 terrorist attack in New York City to the World Trade Center, built in the 1970s, created extra exposure of asbestos, the impact of which will be known only in the coming years [14]. In the dense clouds of dust resulting from this tragic event, relevant quantities of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) produced by the high combustion temperatures were also found, along with other pollutants.

CNTs are nanomaterials composed of graphene sheets consisting of a series of carbon rings rolled into cylindrical fibers with an external measurement between 1 and 100 nm. Their fibrous particulate matter, similar to that of asbestos [15] has raised much concern about their safety for human health. In particular, growing evidence supports the idea that inhaled nanomaterials of >5 μm and with a high aspect ratio (3:1), like rod-like carbon nanotubes resembling asbestos, may cause pleural disease including mesothelioma. In 2014, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified the first type of CNT, the long, rigid, needle-shaped Mitsui-7, as possibly carcinogenic to humans (Group 2B) [16], while in the case of other CNTs, it was not possible to ascertain their toxicity due to lack of evidence. It is also important to consider that, together with the lack of sufficient evidence supporting CNTs’ carcinogenicity, their heterogeneity in chemical and physical structures makes it difficult to generalize the available results regarding their possible hazardous effects on human health.

2. An Overview of Carbon Nanotubes

Thirty years ago, the IBM researcher Don Eigler moved the first individual atom using a scanning tunnelling microscope. Despite that progress, Eigler has said he is not sure about when or even if his ideas for computing will bear fruit. It was Eigler who started the era of nanotechnology, the science that is able to create and manipulate materials at the nanoscale. Nano-sized materials, defined as having at least one dimension between 1 and 100 nm, include many types of materials, different in their physicochemical properties, and used in a great variety of applications [17]. Given the immense potential of nanotechnology, the global nanotechnology market has been estimated to reach 126.8 billion U.S. dollars by 2027 [18].

The big world of nanotechnology comprises various types of nanomaterial, all differing in their chemo-physical properties. CNTs are the most promising type of nanomaterials in the industry today. They are defined as nanotubes composed of carbon, consisting of one or more cylindrical graphene layers and are classified, on the basis of the number of graphene layers, as single- or multi-walled carbon nanotubes (respectively, SWCNTs and MWCNTs). Larger MWCNTs can contain hundreds of concentric layers.

As CNTs come to be used in a wider range of products, human exposure can take place through various routes, such as local (in medical applications, such as drug delivery, cancer therapy, medical diagnostics and imaging), environmental (industrial waste or accidentally released by the final product), or pulmonary (during occupational handling or accidental exposure). The work environment is actually thought to be the principal source of human exposure to CNTs during the phases of their production, as seen for example in laboratory handling and packaging of the final product, and in this case the most plausible route of exposure to manufactured nanomaterials remains pulmonary inhalation. The inhalation of particles during their synthesis is a significant concern in the growing nanotechnology field.

Despite different governmental organizations monitoring CNT exposure in workers, there are still no standards for defining the risk levels for CNT exposure. The method of monitoring CNTs in work environments involves measurement of Elemental Carbon (EC). The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH, USA), based on quantification limits and not on studies in exposed workers, recommends an exposure level of 1 μg/m3 elemental carbon (EC) [19]. This limit, which might not be representative of a safe exposure limit, has often been found to be much lower than those measured in various industries, ranging from 2.6 µg/m3 to 45 µg/m3 depending on the particular workplace analyzed (handling facilities, production areas, construction sites, offices, etc.) [20][21].

The pulmonary toxicity of fibrous materials such as asbestos has been demonstrated to result from deposition (thin fibers deposit in the lungs more efficiently than thick fibers) and tissue persistence (“biopersistence” is directly related to fiber length and inversely related to dissolution and fragmentation rates). CNTs have been demonstrated to deposit in human lungs and other organs. Lung biopsies of people exposed to the dense clouds of dust during the tragic events of 9/11 in New York City have shown the presence of CNTs produced by high combustion temperatures. The first adverse health effects diagnosed were pulmonary fibrosis, and bronchiolocentric parenchymal and granulomatous diseases [14].

Carbon nanotubes, although a sub-group in the immense word of nanomaterials, comprise various substances that differ from each other in length, size, diameter, impurities, and method used for synthesis and dispersion of the final product, among other characteristics. All of these characteristics impact their biological effects, and it is now recognized that generalized conclusions about CNTs should not be drawn by extrapolating data that are available on similar, but not identical, compounds. For these reasons, we focused our analysis on the results obtained using reference CNTs (NM-400, NM-401, NM-402, and NM-403) (https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC91205/mwcnt-online.pdf accessed on 15th October 2020), with fully characterized commercial and in-house CNTs produced using the CVD method, which is currently one of the principal techniques used for CNT synthesis. Data regarding CNTs that had been chemically modified to alter their properties and data obtained in cancer cells were excluded from our analysis; this model is suitable for other purposes, such as drug-delivery studies, which are not the focus of this review.

We reported data relevant to assessing the potential adverse respiratory effects following the IARC’s protocol for defining an agent as a human carcinogen [22]. For each group of characteristics, we analyzed data obtained from in vitro models of pleura, lung macrophages, and airway cells, from in vivo studies examining effects on the respiratory system, and from biological fluids collected from exposed workers, highlighting those results that could be relevant for mesothelioma onset.

3. Carbon Nanotubes and the Hallmarks of Cancer

3.1. Oxidative Stress, Chronic Inflammation

The oxidative potential of a particle is the intrinsic property to form reactive oxygen species (ROS). Generation of ROS and free radicals has been demonstrated to be involved in the molecular mechanisms leading to mesothelioma as well as other asbestos-related diseases. In cell-free systems, asbestos can generate free radicals and induce release of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, growth factors, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in neutrophils, and alveolar macrophages for incomplete/frustrated phagocytosis of fibers. At cellular level, in asbestos exposed cells, inflammation, oxidative stress, and carcinogenesis has been associated with the alteration of the iron metabolism due to iron accumulation on fibers [23]. Similarly, iron impurities in CNTs have been demonstrated to participate in increased inflammation and oxidative stress in CNTs exposed mesothelial cells, in a “dose-dependent” manner [24][25][26].

At the molecular level, ROS may cause different injuries, such as gene mutations and structural alterations to the DNA, leading to deregulation in cell proliferation and apoptosis. Oxidative DNA damage is often characteristic of chronic inflammation, one of the main mechanisms underlying mesothelial transformation.

During the inflammation process, the cross-talk between inflammatory cells and damaged alveolar cells has been recognized to contribute to mesothelioma pathogenesis as well as other respiratory disease like lung fibrosis and lung cancer [27][28]. Lung fibrosis manifests with excessive deposition of collagen fibers in the extracellular matrix (ECM) and remodelling of the alveolar parenchyma, leading to a progressive loss of lung function. It includes a first acute inflammation phase where inflammatory cells infiltrate the tissue, secrete proinflammatory mediators (cytokines TNFα, IL1α, IL1β, IL6, chemokine CCL2, and fibrogenic growth factors TGF-β1 and PDGF-A), and collagen is deposited in the ECM. After this early response, granulomatous fibrotic foci deposits around the lesions are detectable. Activation of fibroblasts and formation of myofibroblasts (fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition) and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of alveolar type II cells are drivers of this process [29][30]. Lung fibrosis is one of the first documented injuries to lung described in asbestos-exposed workers 2,3 and the inflammatory process leading to fibrosis has been well characterized using long, needle-like Mitsui-7 MWCNT exposure in vivo [31][32]. The role of oxidative stress in CNTs-induced lung fibrosis was demonstrated through the use of the antioxidant N-Acetyl Cysteine, which interfered with NLRP3 inflammasome activation and generation of pulmonary fibrosis in mice [33].

In both asbestos- and MWCNT-exposed workers, markers of fibrosis, profibrotic inflammatory mediators and immune markers [20][34][35], as well as dysregulation in mRNAs and target genes linked to the activation of key pathways involved in several disease outcomes (e.g., cancer, respiratory and cardiovascular disease, and fibrosis) [36] have been found. Markers of oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction have also been found in exposed workers [37].

The similarity between MWCNTs and asbestos due to their inflammatory and oxidative potential has been recently demonstrated in vivo with long MWCNTs (Nanostructured & Amorphous Materials, Houston, TX, USA; University of Manchester, Manchester, UK) and long fiber amosite asbestos instilled into the pleural cavity of mice. Exposure to long fibers but not to short fibers resulted in the development and progression of inflammatory lesions along the pleura and in the increase of markers of oxidative stress and genotoxicity. All exposed animals displayed pleural lesions (mesothelial hyperplasia and fibrosis), and chronic inflammation and, in 10–25% of animals exposed to long MWCNTs, the lesions progressed to pleural mesothelioma [38]. Different results were obtained with long NM-401 and Mitsui-7 MWCNTs. In this study, toxicity and inflammation were observed only in mice exposed to short MWCNTs (NM-400, NM-402, NM-403, and MWCNTs from CheapTubes, Brattleboro, VT, USA) [39].

However, other studies in vivo have demonstrated that both long and short industrial MWCNTs induced granulomatous changes in the lungs, development of pulmonary fibrosis, and inflammation accompanied by increase in vimentin, TGF-beta, IL-1b, IL-18, and cardiac fibrotic deposition [40][41][42][43][44]. Commercial short MWCNTs (tangled) (Graphistrength© C100; Arkema, France) showed prolonged TNF-α release in BAL of exposed rats associated with increased collagen staining [45].

Similar results were obtained with SWCNTs (Nikkiso Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), showing strong persistent pulmonary inflammation [46]. The same group also demonstrated that the shorter the length of SWCNTs is, the stronger the toxicity. Short SWCNTs (Nikkiso Co., LTD., Tokyo, Japan) with a length of 2.8 µm induced a weaker inflammatory response and pulmonary toxicity than those with a length of 0.4 µm [42].

It has also been demonstrated that chronic exposure to commercial short SWCNTs (CNI, Houston, TX, USA) induces tumor growth (subcutaneously injected) and metastasis to liver and lung through activation of EMT [47]. Cancer development (Bronchiolo-alveolar adenoma and carcinoma) was also found in 18% of mice exposed to a single intratracheal instillation of short SWCNT (Nikkiso Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) [46].

For a long time, length has been considered a predictor of CNTs’ adverse biological effects. However, even if this is true in some cases, many in vitro studies support the concept that the length of CNTs might not be a unique determinant of the biological response. Recently, shape and diameter have been correlated with accessibility to the macrophage interior subsequently affecting their degradation ability and, therefore, ROS production. Since alveolar clearance contributes to inhalation toxicity, the understanding of parameters predicting CNT toxicity is of crucial importance. This question has been challenged in many studies. Rigid, needle-shaped, long Mitsui-7 MWCNTs (diameter > 50 µm), which are poorly uptaken into phagosomes of alveolar macrophages, have been demonstrated to not induce ROS release. On the contrary, curved, straight, long and thin MWCNTs from different manufacturers, with diameters <20 µm which localize in vacuole-like compartments, have been demonstrated to generate intracellular ROS. For all the analyzed MWCNTs, increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, MIP-1α, INF-γ, IL-18, MCP-1, and TNF-α) were found, implying that the inflammatory response might not be strictly related to the phagocytic ability of the macrophages [48]. ROS production from lung cells could be responsible for the inflammatory response of macrophages in the absence of phagocytic activity. While the rigid, straight, “needle-like” NM-401 MWCNTs, which are similar to Mitsui-7, are poorly uptaken by macrophages and do not cause an increase in NO production, lung fibroblast cells (V79) were demonstrated to be able to uptake NM-401, with 80% of fibers localized in endosomes, generating a consistent production of intracellular ROS [49]. Short NM-400 and NM-402 MWCNTs with a diameter <20 µm, are instead efficiently degraded by macrophages and induce an increase in NO accompanied by acute inflammation [50].

Markers of inflammation and oxidative stress were also studied in epithelial cells. Induction of oxidative stress have been described in lung epithelial cells exposed to NM-402 and NM-403 with values comparable to or higher than that of Mitsui-7 [51] while in BEAS-2B cells, a significant reduction in the levels of mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 and an increase in the antioxidant HO-1 gene were found in long-term exposure (three weeks) to NM-403 [52]. However the authors associated these contradictory findings to the metal contaminants present in NM-403.

As a driver of lung fibrosis, the activation of the EMT program in lung epithelial cells by fibrous materials has been documented in four different studies in airway epithelial cells. Exposure to chrysotile asbestos, SWCNTs, Mitsui-7, and Mitsui-7-derived MWCNTs with the length reduced to 1.12 µm, at sub-toxic concentrations led to an increase in mesenchymal markers (α-smooth muscle actin, vimentin, metalloproteinases, and fibronectin), a decrease in epithelial markers (E-cadherin and β-catenin), and activation of the TGF-β–mediated signaling pathway [40][53][54].

Fibrogenic potential was also demonstrated with an in-house lung microtissue array device in airway epithelial cells exposed to non-toxic concentrations of short MWCNTs (CheapTubes.com accessed on 15th of October 2020) together with a significant increase in expression of the fibrogenic marker miR-21. These effects were not found in cells exposed to long MWCNTs [55].

All of the results reported above indicate that physico-chemical characteristics such as length and diameter could partially explain the different biological responses but, alone, might not be predictive of inflammatory response. Many variables such as the presence of CNTs of different lengths in the same preparation together with their heterogeneity in experimental settings contribute to the difficulty in predicting their inflammatory and oxidative effects. Particularly in in vivo studies (Table 1 and Table 2), different route of exposure and different endpoints analyzed have been used for the evaluation of pathological parameters. Even though studies comparing the inhalation and instillation of MWCNT showed that both methods induced pulmonary inflammation [56], inhalation is more powerful in inducing inflammation [57] and should be the preferred method for studies on accidental exposure during the manufacturing process since it recreates real situations better.

Table 1. Cancer development, histological changes, and inflammatory response observed in in vivo experiments with MWCNTs.

| CNTs | Length (µm); Diameter (nm) | Cancer | Histological Changes | Inflammation | Exposure Route | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitsui-7 | L: 3–5.7 D: 49–100 |

x | x | intratracheal instillation | [58] | |

| Mitsui-7 | L: 3–5.7 D: 49–100 |

bronchiolo-alveolar adenoma and adenocarcinoma | x | x | whole body inhalation | [32] |

| Mitsui-7 | L: 5.7 ± 0.49; D: 74 (29–173) |

intratracheal instillation | [39] | |||

| Short MWCNTs | L: 1.12 ± 0.05 D: 67 ± 2 |

x | pharyngeal aspiration | [40] | ||

| Industrial MWCNTs | L: 2–15; D: 8–15 |

x | x | pharyngeal aspiration | [41] | |

| Long MWCNTs (Nikkiso similar to Mitsui-7) | L: 1–10; D: 1–20 |

pleural malignant mesothelioma and lung tumors | intratracheally instilled | [59] | ||

| Long MWCNTs (University of Manchester, UK) | L: 85% > 15 D: 165 + 4.7 |

mesothelial hyperplasia; mesothelioma | x | x | instilled into the pleural cavity | [38] |

| MWCNTs (Nanostructured & Amorphous Materials, USA) | L: <15; D: 125 |

instilled into the pleural cavity | [38] | |||

| NM-400 | L: 0.85 ± 0.10; D: 11 ± 3 |

x | intratracheally instilled | [39] | ||

| NM-401 | L: 4.0 ± 0.37; D: 67 ± 24 |

intratracheal instillation | [39] | |||

| NM-402 | L: 1.4 ± 0.19; D: 11 ± 3 |

x | x | intratracheal instillation | [58] | |

| NM-402 | L: 1.4 ± 0.19; D: 11 ± 3 |

x | intratracheal instillation | [39] | ||

| NM-403 | L: 0.4 ± 0.03; D: 12 ± 7 |

x | intratracheal instillation | [39] | ||

| MWCNTs Nanotechcenter Ltd. | L: 2–15; D: 8–15 |

x | pharyngeal aspiration | [44] | ||

| MWCNTs(Cheaptube) | L: 0.52 (±0.59); D: 20.56 (±6.94) |

x | intratracheal instillation | [60] | ||

| MWCNTs(Cheaptube) | L: 0.77 (±0.35) D: 26.73 (±6.88) |

x | intratracheal instillation | [60] | ||

| MWCNTs(Cheaptube) | L: 0.72 (±1.2) D: 17.22 (±5.77) |

x | intratracheal instillation | [60] |

Abbreviations: “x”: studies that have reported a relationship between these characteristics and exposure to the material.

Table 2. Cancer development, histological changes, and inflammatory response observed in in vivo experiments with SWCNTs.

| CNTs | Length (µm); Diameter (nm) | Cancer | Inflammation | Exposure Route | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWCNTs Graphistrength© C100 | L: 1.06 mean; D: 11.9 mean |

x | nose-only inhalation exposure | [45] | |

| Short SWCNTs (Nikkiso & Co., LTD) | L: 0.55 ± 0.36; D: 1.4 ± 0.7 |

bronchiolo-alveolar adenoma and adenocarcinoma (18% of mice) | intratracheal instillation | [46] |

Abbreviations: “x”: studies that have reported a relationship between these characteristics and exposure to the material.

3.2. Epigenetic Alterations

It is well known that epigenetic changes in DNA and RNA play an important role in the regulation of gene expression by changing DNA accessibility to the cellular machinery, and switching on/off gene expression. As indicators of environmental insults, the study of epigenetics is a useful tool to understand disease-related mechanisms as well as serve as an indicator of disease risk. Among the epigenetic modifications affecting the genome, DNA methylation, the process by which a methyl group is added to carbon five in the cytosine pyridine ring forming 5-methylcytosine (5 mC) in DNA, is the most studied for the assessment of the potential hazard of fiber-like materials. Mesothelioma, as well other asbestos-related diseases, has been related to epigenetic changes, and the methylation changes of blood markers have been proposed as diagnostic and prognostic markers for mesothelioma [61][62][63]. In recent epidemiological studies in asbestos-exposed populations, a decrease in the levels of blood global 5-methylcytosine (5 mC) has been described in both healthy exposed workers and in those with benign asbestos-related disorders, confirming that global methylation could be a useful marker of asbestos exposure but, unfortunately, cannot be used as indicator of asbestos-related disease [64][65].

In MWCNT-exposed workers, changes in the methylation of specific genes mainly involved in DNA damage repair, cell cycle regulation, chromatin remodelling, and transcriptional repression (DNMT1, ATM, SKI and HDAC4 promoter) was described in a cross-sectional study [21]. Unlike with asbestos, no significant difference was found in total DNA methylation.

Hypermethylation of specific genes was also found in mice exposed to long MWCNTs (Nanostructured & Amorphous Materials, Houston, TX, USA; University of Manchester, UK) and long amosite fibers, which caused chronic inflammatory lesions or mesothelioma. Of particular importance is the epigenetic silencing of the CDKN2A locus, a well-known driver mutation in asbestos-induced mesothelioma, observed in mice exposed to both long MWCNTs and long amosite fibers [38].

Many in vitro studies have confirmed the methylation of specific genes. In 16HBE airway epithelial cells, in-house synthesized short MWCNTs and SWCNTs induced differentially methylated and expressed genes in cellular pathways related to DNA damage repair and cell cycle, with more pronounced effects in MWCNTs. No alteration of global DNA methylation was found [66]. An increased alteration on CpG sites after short -and long-term exposure has also been described for both benchmark short NM-400 MWCNTs and asbestos (CDKN1A and ATM among others) [66][67][68][69][70].

Together with specific gene methylation, other studies have also found a strong genome-wide DNA hypomethylation in airway epithelial cells (BEAS-2B and 16HBE) exposed to commercial short MWCNTs (CheapTubes, Brattleboro, VT, USA) and NM-400 and NM-401 [67][68][69][71].

It is important to note that most of the hypomethylated genes observed after two weeks of exposure to NM-401 became hypermethylated after four weeks of exposure [67], thus highlighting how time and particle type can trigger different and apparently discordant results.

In conclusion, many studies have demonstrated that change in methylation can be used as a marker of exposure to CNTs but heterogeneity of this class of nanomaterial does not allow for making generalizations. More studies are needed to expand our knowledge about epigenetic regulation of specific genes after CNT exposure. Given our current knowledge of asbestos, we know what genes are strictly linked to mesothelioma onset, and the results regarding epigenetic changes reported above suggest that CNTs could act via a similar mechanism.

3.3. Genotoxicity, Alteration in DNA Repair, and Genome Instability

Genotoxic effects can result from primary or secondary mechanisms. The first implies a direct interaction with the genetic material, the latter the oxidation of DNA by reactive oxygen/nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) generated during substance-induced inflammation. Both mechanisms could be involved in the genotoxic response elicited by MWCNTs.

Although CNTs are considered by IARC to be usually non-reactive and, for Mitsui-7 genotoxicity, have been demonstrated to act via secondary mechanisms, it cannot be excluded that defects in their structure occurring during the synthesis or functionalization could increase their reactivity [72][73]. Very recently, for long and short SWCNTs, the nucleus has been hypothesized to be the primary target site with DNA damage likely due to mechanical penetration [74].

Many studies, such as those described above, support the hypothesis that CNT genotoxicity could result from secondary mechanisms triggered by a strong inflammatory response and ROS release.

A genotoxicity study recently conducted in workers exposed to CNTs (unspecified manufacturer), revealed an 18.3% increase in telomere length and a 35.2% increase in mitochondrial DNA copy number from peripheral blood [75].

Asbestos-induced mesothelioma has been linked to polyploidization and aneuploidization, and MWCNTs seem to have similar adverse effects [76]. Chromosomal aberrations (polyploidy), and mitotic and chromosomal disruptions have been demonstrated for commercial MWCNTs (Hodogaya Chemical, Tokyo, Japan; Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan; Showa Denko K.K, Tokyo, Japan), including MWCNT-7, with different length and shape (including straight fibrous, not straight fibrous (curved), and tangled MWCNTs) in Chinese hamster lung cell lines with straight fibrous being the more potent inducers of polyploidy. None of the seven MWCNTs analyzed caused structural chromosomal aberrations [76]. In the same model, NM-401 was found to be genotoxic, increasing HPRT mutant frequency [49].

In vivo experiments with long MWCNTs (Mitsui & Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) showed a significant increase in DNA damage (comet assay) in the cells of lungs with straight MWCNTs but not with tangled MWCNTs. Moreover, straight MWCNTs caused an increase in DNA strand breaks in BAL cells collected after inhalation but not after pharyngeal aspiration [77]. DNA strand breaks were also observed after intratracheal instillation of straight NM-401 MWCNTs in the transgenic MutaTMMouse model. Moreover, both straight NM-401 and Mitsui-7 MWCNTs increased p53 expression predominantly in the area of fibrotic lesions (more pronounced for NM-401), and induced chronic inflammation and changes in the expression of genes linked to hallmarks of cancer. There was no evidence of a LacZ mutation [58].

Short commercial MWCNTs comprised of straight and tangled MWCNTs (CheapTube, Brattleboro, VT, USA), were demonstrated to induce a dose- and time- dependent neutrophil influx in BAL and to cause DNA damage in the lungs of mice exposed by intratracheal instillation, with large MWCNTs diameter associated with increased genotoxicity (Analysis at 1, 28 and 92 days after exposure). All MWCNTs analyzed induced similar histological changes [60].

Another study using commercial short tangled MWCNTs (Graphistrength© C100; Arkema, France) did not disclose genotoxicity in lung cells or a microscopic change in the pleura. As the authors hypothesized, these effects could in part be ascribed to the formation of agglomerates that are poorly uptaken by cells [45]. However, the lack of a positive control in the experimental setting could represent a weakness in the study.

Similar results have been seen in in vitro studies. Long-term exposure of primary human airway epithelial cells (SAECs) to commercial short SWCNTs (CNI, Houston, TX, USA), long Mitsui-7 MWCNTs (Mitsui & Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and Crocidolite, and mesothelial MeT-5A cells exposed to commercial long MWCNTs (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) have demonstrated a substantial increase in DNA damage in γH2A.X foci and p53 dysregulation [54][78].

Chromosome damage and chromosome mis-segregation have also been described in airway epithelial cells chronically exposed to sub-toxic doses of short NM-400 and NM-403 MWCNTs [52], while no primary DNA damage or oxidized DNA bases have been observed in short-term experiments with NM-400, NM-401, and NM-403 [50][79][80]

Contrasting results for Micronuclei (MN) formation assay were found in NM-401-exposed cells, according to the different methods used. With the cytokinesis-blocked micronucleus assay (CBMN), authors did not observe significant increases in the frequency of micronucleated binucleated cells or induction of DNA damage by the comet assay [81]. When analyzed by flow cytometry, NM-401 at 20 and 50 µg/mL were able to increase the MN formation [79]. No genotoxic effects with the CBMN assay were detected also for NM-400, NM-402, and NM-403 [81].

Bacterial reverse mutation tests and chromosomal aberration tests, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Testing of Chemicals, were conducted on straight, long, thin MWCNTs, revealing no structural or numerical chromosomal aberrations below a concentration of 50 µg/mL following short-term exposure, both with and without metabolic activation [48]. However, this test is not suitable for studies with nanomaterials since they are not able to enter the bacterial cell wall, thus leading to the production of false-negative results.

Even though a definitive conclusion on the genotoxicity of CNTs is still impossible to draw, many results have indicated the presence of damaged DNA after exposure to CNTs. It is clear that for genotoxicity assessment, many variables, in addition to those mentioned previously, could interfere with the results. In particular, due to different responses in terms of DNA repair of different cell types, in vitro and in vivo models used represent a key factor together with the dose and time chosen for the analysis.

3.4. Immortalization, Altered Cell Proliferation, Cell Death, or Nutrient Supply

MWCNT-7 carcinogenicity has been demonstrated by different studies in mice in which the whole body has been exposed [82][83]. Nikkiso MWCNTs, which is similar to Mitsui-7, have also been demonstrated to induce pleural malignant mesothelioma and lung tumors in intratracheal instillation studies [59].

The transformation potential in vitro has been documented in different studies. After long-term exposure to commercial long MWCNTs (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), mesothelial MeT-5A cells showed features resembling a malignant transformation process and specifically an increase in cell proliferation and invasion capacity, morphology change, and DNA damage [78].

Similarly, after long-term exposure to short SWCNTs (CNI, Houston, TX, USA), Mitsui-7 (Mitsui & Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and Crocidolite asbestos, primary human small airway epithelial cells (SAECs) exhibited neoplastic and cancer stem cell-like properties, such as anchorage-independent colony formation, spheroid formation, anoikis resistance, and expression of cancer stem cell markers [54].

Altered cell proliferation was also described. Cell growth inhibition with benchmark NM-403 MWCNTs [52], and NM-400 and NM401 MWCNTs have been demonstrated in bronchial epithelial cells in long-term experiments [84] and, for NM401 and NM403, in short-term experiments without significant cytotoxicity [51].

Similar results were obtained with commercial short SWCNTs and MWCNTs (SES Research, USA; Heji, Hong Kong, China), in lung fibroblasts and in epithelial cells with short rod-like SWCNTs and straight MWCNTs showing higher toxicity [77][85][86].

Toxicity studies in macrophages mostly supported the hypothesis that rigidity and high diameters are as key factors underlying toxicity. Indeed, exposure to rigid, needle-shaped Mitsui-7 MWCNTs, and Nikkiso and NM-401 MWCNTs all induce cytotoxicity in macrophage cells while NM-400 and NM-402 did not [48][50]. However, the opposite has also been described in rat alveolar macrophages acutely exposed to highly bent, low-diameter NM-403 MWCNTs, which induced significant toxicity [87].

3.5. Immunosuppression, Modulation of Receptor-Mediated Effects, and Electrophilicity

Few data are available regarding the characteristics grouped below.

Available studies have demonstrated that CNTs can interact and activate the complement system, a key part of the immune system, and induce an early and sustained immunosuppressive response [44][88][89][90]. Moreover, it has been shown that SWCNT exposure in mice increases susceptibility to respiratory viral infections [91].

The ability of CNTs to act as an electrophile and then interact with cellular macromolecules, such as DNA, RNA, lipids, and proteins, has not been thoroughly investigated. It has been suggested that SWCNTs block K+ channel subunits by “plugging” the channel by virtue of the small diameter [92] and interact with TLR4 by hydrophobic interactions [93].

All of these studies suggest that the immunosuppression and modulation of the immune responses elicited by CNTs need further investigation. Indeed, an increased susceptibility to pathogens as well as immunosuppression could be a new and potentially significant mechanism of toxicity in humans.

References

- National Research Council. Asbestiform Fibers: Nonoccupational Health Risks; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1984.

- Committee on Compensation for Industrial Diseases. Report of the Departmental Committee on Compensation for Industrial Diseases; Wyman & Sons: London, UK, 1907.

- Cooke, W.E. Fibrosis of the lungs due to the inhalation of asbestos dust. BMJ 1924, 2, 140–142, 147.

- Cooke, W.E. Pulmonary asbestosis. BMJ 1927, 2, 1024–1025.

- Gloyne, S.R. Two cases of squamous carcinoma of the lung occurring in asbestosis. Tubercle 1935, 17, 5–10.

- Lynch, K.M.; Smith, W.A. Pulmonary Asbestosis III: Carcinoma of Lung in Asbesto-Silicosis. Am. J. Cancer 1935, 24, 56–64.

- Wedler, H.-W. Asbestose und Lungenkrebs. DMW Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 1943, 69, 575–576.

- Wyers, H. That Legislative Measures Have Proved Generally Effective in the Control of Asbestosis. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK, 1946.

- International Agency Research on Cancer. Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Human; IARC: Lyon, France, 1977.

- Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on Asbestos: Selected Health Effects; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1987.

- Committee I of M (US). Asbestos: Selected Cancers; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006.

- Straif, K.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Baan, R.; Grosse, Y.; Secretan, B.; El Ghissassi, F.; Bouvard, V.; Guha, N.; Freeman, C.; Galichet, L.; et al. A review of human carcinogens—Part C: Metals, arsenic, dusts, and fibres. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 453–454.

- Terracini, B. Contextualising the policy decision to ban asbestos. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e331–e332.

- Wu, M.; Gordon, R.E.; Herbert, R.; Padilla, M.; Moline, J.; Mendelson, D.; Litle, V.; Travis, W.D.; Gil, J. Case Report: Lung disease in world trade center responders exposed to dust and smoke: Carbon nanotubes found in the lungs of world trade center patients and dust samples. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 499–504.

- Donaldson, K.; Poland, C.A.; Murphy, F.A.; MacFarlane, M.; Chernova, T.; Schinwald, A. Pulmonary toxicity of carbon nanotubes and asbestos—Similarities and differences. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 2078–2086.

- Grosse, Y.; Loomis, D.; Guyton, K.Z.; Lauby-Secretan, B.; El Ghissassi, F.; Bouvard, V.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Guha, N.; Scoccianti, C.; Mattock, H.; et al. Carcinogenicity of fluoro-edenite, silicon carbide fibres and whiskers, and carbon nanotubes. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 1427–1428.

- De Menezes, B.R.C.; Rodrigues, K.F.; Fonseca, B.C.D.S.; Ribas, R.G.; Montanheiro, T.L.D.A.; Thim, G.P. Recent advances in the use of carbon nanotubes as smart biomaterials. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 1343–1360.

- Globe Newswire. Global Nanotechnology Industry; Globe Newswire: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Centre for Disease Control and Prevention: CURRENT Intelligence Bulletin 65: Occupational Exposure to Carbon Nanotubes and Nanofibers; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013.

- Fatkhutdinova, L.M.; Khaliullin, T.O.; Vasil’Yeva, O.L.; Zalyalov, R.R.; Mustafin, I.G.; Kisin, E.R.; Birch, M.E.; Yanamala, N.; Shvedova, A.A. Fibrosis biomarkers in workers exposed to MWCNTs. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2016, 299, 125–131.

- Ghosh, M.; Öner, D.; Poels, K.; Tabish, A.M.; Vlaanderen, J.; Pronk, A.; Kuijpers, E.; Lan, Q.; Vermeulen, R.; Bekaert, B.; et al. Changes in DNA methylation induced by multi-walled carbon nanotube exposure in the workplace. Nanotoxicology 2017, 11, 1195–1210.

- International Agency Research on Cancer. Some Nanomaterials and Some Fibres; IARC: Lyon, France, 2017; p. 111.

- Toyokuni, S. Iron overload as a major targetable pathogenesis of asbestos-induced mesothelial carcinogenesis. Redox Rep. 2013, 19, 1–7.

- Cammisuli, F.; Giordani, S.; Gianoncelli, A.; Rizzardi, C.; Radillo, L.; Zweyer, M.; Da Ros, T.; Salomé, M.; Melato, M.; Pascolo, L. Iron-related toxicity of single-walled carbon nanotubes and crocidolite fibres in human mesothelial cells investigated by Synchrotron XRF microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 706.

- Muller, J.; Decordier, I.; Hoet, P.H.; Lombaert, N.; Thomassen, L.; Huaux, F.X.; Lison, D.; Kirsch-Volders, M. Clastogenic and aneugenic effects of multi-wall carbon nanotubes in epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis 2008, 29, 427–433.

- Kagan, V.; Tyurina, Y.; Tyurin, V.; Konduru, N.; Potapovich, A.; Osipov, A.; Kisin, E.; Schwegler-Berry, D.; Mercer, R.; Castranova, V.; et al. Direct and indirect effects of single walled carbon nanotubes on RAW 264.7 macrophages: Role of iron. Toxicol. Lett. 2006, 165, 88–100.

- Digifico, E.; Belgiovine, C.; Mantovani, A.; Allavena, P. Microenvironment and immunology of the human pleural malignant mesothelioma BT—Mesothelioma: From research to clinical practice. In Mesothelioma; Ceresoli, G.L., Bombardieri, E., D’Incalci, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 69–84.

- Mittal, V.; El Rayes, T.; Narula, N.; McGraw, T.E.; Altorki, N.K.; Barcellos-Hoff, M.H. The Microenvironment of lung cancer and therapeutic implications. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 890, 75–110.

- Dong, J.; Ma, Q. Myofibroblasts and lung fibrosis induced by carbon nanotube exposure. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2016, 13, 1–22.

- Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Nie, X.; Braïni, C.; Bai, R.; Chen, C. Multiwall Carbon nanotubes directly promote fibroblast-myofibroblast and epithelial-mesenchymal transitions through the activation of the TGF-β/smad signaling pathway. Small 2014, 11, 446–455.

- Dong, J.; Porter, D.W.; Batteli, L.A.; Wolfarth, M.G.; Richardson, D.L.; Ma, Q. Pathologic and molecular profiling of rapid-onset fibrosis and inflammation induced by multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Arch. Toxicol. 2014, 89, 621–633.

- Snyder-Talkington, B.N.; Dong, C.; Sargent, L.M.; Porter, D.W.; Staska, L.M.; Hubbs, A.F.; Raese, R.; McKinney, W.; Chen, B.T.; Battelli, L.; et al. mRNAs and miRNAs in whole blood associated with lung hyperplasia, fibrosis, and bronchiolo-alveolar adenoma and adenocarcinoma after multi-walled carbon nanotube inhalation exposure in mice. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2016, 36, 161–174.

- Sun, B.; Wang, X.; Ji, Z.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.-P.; Chang, C.H.; Li, R.; Zhang, H.; Nel, A.E.; Xiang, W. NADPH oxidase-dependent nlrp3 inflammasome activation and its important role in lung fibrosis by multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Small 2015, 11, 2087–2097.

- Vlaanderen, J.; Pronk, A.; Rothman, N.; Hildesheim, A.; Silverman, D.; Hosgood, H.D.; Spaan, S.; Kuijpers, E.; Godderis, L.; Hoet, P.; et al. A cross-sectional study of changes in markers of immunological effects and lung health due to exposure to multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Nanotoxicology 2017, 11, 395–404.

- Beard, J.D.; Erdely, A.; Dahm, M.M.; de Perio, M.A.; Birch, M.E.; Evans, D.E.; Fernback, J.E.; Eye, T.; Kodali, V.; Mercer, R.R.; et al. Carbon nanotube and nanofiber exposure and sputum and blood biomarkers of early effect among U.S. workers. Environ. Int. 2018, 116, 214–228.

- Shvedova, A.A.; Yanamala, N.; Kisin, E.R.; Khailullin, T.O.; Birch, M.E.; Fatkhutdinova, L.M. Integrated Analysis of Dysregulated ncRNA and mRNA Expression Profiles in Humans Exposed to Carbon Nanotubes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150628.

- Lee, J.S.; Choi, Y.C.; Shin, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, Y.; Park, S.Y.; Baek, J.E.; Park, J.D.; Ahn, K.; Yu, I.J. Health surveillance study of workers who manufacture multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Nanotoxicology 2014, 9, 802–811.

- Chernova, T.; Murphy, F.A.; Galavotti, S.; Sun, X.-M.; Powley, I.R.; Grosso, S.; Schinwald, A.; Zacarias-Cabeza, J.; Dudek, K.M.; Dinsdale, D.; et al. Long-Fiber carbon nanotubes replicate asbestos-induced mesothelioma with disruption of the tumor suppressor gene Cdkn2a (Ink4a/Arf). Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 3302–3314.e6.

- Knudsen, K.B.; Berthing, T.; Jackson, P.; Poulsen, S.S.; Mortensen, A.; Jacobsen, N.R.; Skaug, V.; Szarek, J.; Hougaard, K.S.; Wolff, H.; et al. Physicochemical predictors of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube-induced pulmonary histopathology and toxicity one year after pulmonary deposition of 11 different Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes in mice. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 124, 211–227.

- Polimeni, M.; Gulino, G.R.; Gazzano, E.; Kopecka, J.; Marucco, A.; Fenoglio, I.; Cesano, F.; Campagnolo, L.; Magrini, A.; Pietroiusti, A.; et al. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes directly induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human bronchial epithelial cells via the TGF-β-mediated Akt/GSK-3β/SNAIL-1 signalling pathway. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2015, 13, 1–19.

- Khaliullin, T.O.; Shvedova, A.A.; Kisin, E.R.; Zalyalov, R.R.; Fatkhutdinova, L.M. Evaluation of fibrogenic potential of industrial multi-walled carbon nanotubes in acute aspiration experiment. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2015, 158, 684–687.

- Ema, M.; Takehara, H.; Naya, M.; Kataura, H.; Fujita, K.; Honda, K. Length effects of single-walled carbon nanotubes on pulmonary toxicity after intratracheal instillation in rats. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 42, 367–378.

- Davis, G.; Lucero, J.; Fellers, C.; McDonald, J.D.; Lund, A.K. The effects of subacute inhaled multi-walled carbon nanotube exposure on signaling pathways associated with cholesterol transport and inflammatory markers in the vasculature of wild-type mice. Toxicol. Lett. 2018, 296, 48–62.

- Khaliullin, T.O.; Yanamala, N.; Newman, M.S.; Kisin, E.R.; Fatkhutdinova, L.M.; Shvedova, A.A. Comparative analysis of lung and blood transcriptomes in mice exposed to multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2020, 390, 114898.

- Pothmann, D.; Simar, S.; Schuler, D.; Dony, E.; Gaering, S.; Le Net, J.-L.; Okazaki, Y.; Chabagno, J.M.; Bessibes, C.; Beausoleil, J.; et al. Lung inflammation and lack of genotoxicity in the comet and micronucleus assays of industrial multiwalled carbon nanotubes Graphistrength© C100 after a 90-day nose-only inhalation exposure of rats. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2015, 12, 21.

- Honda, K.; Naya, M.; Takehara, H.; Kataura, H.; Fujita, K.; Ema, M. A 104-week pulmonary toxicity assessment of long and short single-wall carbon nanotubes after a single intratracheal instillation in rats. Inhal. Toxicol. 2017, 29, 471–482.

- Wang, P.; Voronkova, M.; Luanpitpong, S.; He, X.; Riedel, H.; Dinu, C.Z.; Wang, L.; Rojanasakul, Y. Induction of Slug by Chronic Exposure to Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Promotes Tumor Formation and Metastasis. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2017, 30, 1396–1405.

- Fujita, K.; Obara, S.; Maru, J.; Endoh, S. Cytotoxicity profiles of multi-walled carbon nanotubes with different physico-chemical properties. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2020, 30, 477–489.

- Rubio, L.; El Yamani, N.; Kazimirova, A.; Dusinska, M.; Marcos, R. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (NM401) induce ROS-mediated HPRT mutations in Chinese hamster lung fibroblasts. Environ. Res. 2016, 146, 185–190.

- Di Cristo, L.; Bianchi, M.G.; Chiu, M.; Taurino, G.; Donato, F.; Garzaro, G.; Bussolati, O. Chiu comparative in vitro cytotoxicity of realistic doses of benchmark multi-walled carbon nanotubes towards macrophages and airway epithelial cells. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 982.

- Jackson, P.; Kling, K.; Jensen, K.A.; Clausen, P.A.; Madsen, A.M.; Wallin, H.; Vogel, U. Characterization of genotoxic response to 15 multiwalled carbon nanotubes with variable physicochemical properties including surface functionalizations in the FE1-Muta (TM) mouse lung epithelial cell line. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2014, 56, 183–203.

- Vales, G.; Rubio, L.; Marcos, R. Genotoxic and cell-transformation effects of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) following in vitro sub-chronic exposures. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 306, 193–202.

- Gulino, G.R.; Polimeni, M.; Prato, M.; Gazzano, E.; Kopecka, J.; Colombatto, S.; Ghigo, D.; Aldieri, E. Effects of chrysotile exposure in human bronchial epithelial cells: Insights into the pathogenic mechanisms of asbestos-related diseases. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 776–784.

- Kiratipaiboon, C.; Stueckle, T.A.; Ghosh, R.; Rojanasakul, L.W.; Chen, Y.C.; Dinu, C.Z.; Rojanasakul, Y. Acquisition of cancer stem cell-like properties in human small airway epithelial cells after a long-term exposure to carbon nanomaterials. Environ. Sci. Nano 2019, 6, 2152–2170.

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Q.; Asmani, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, C.; Lippmann, J.M.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, R. Lung microtissue array to screen the fibrogenic potential of carbon nanotubes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31304.

- Gaté, L.; Knudsen, K.B.; Seidel, C.; Berthing, T.; Chézeau, L.; Jacobsen, N.R.; Valentino, S.; Wallin, H.; Bau, S.; Wolff, H.; et al. Pulmonary toxicity of two different multi-walled carbon nanotubes in rat: Comparison between intratracheal instillation and inhalation exposure. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2019, 375, 17–31.

- Shvedova, A.A.; Kisin, E.; Murray, A.R.; Johnson, V.J.; Gorelik, O.; Arepalli, S.; Hubbs, A.F.; Mercer, R.R.; Keohavong, P.; Sussman, N.; et al. Inhalation vs. aspiration of single-walled carbon nanotubes in C57BL/6 mice: Inflammation, fibrosis, oxidative stress, and mutagenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2008, 295, L552–L565.

- Rahman, L.; Jacobsen, N.R.; Aziz, S.A.; Wu, D.; Williams, A.; Yauk, C.L.; White, P.; Wallin, H.; Vogel, U.; Halappanavar, S. Multi-walled carbon nanotube-induced genotoxic, inflammatory and pro-fibrotic responses in mice: Investigating the mechanisms of pulmonary carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2017, 823, 28–44.

- Suzui, M.; Futakuchi, M.; Fukamachi, K.; Numano, T.; Abdelgied, M.; Takahashi, S.; Ohnishi, M.; Omori, T.; Tsuruoka, S.; Hirose, A.; et al. Multiwalled carbon nanotubes intratracheally instilled into the rat lung induce development of pleural malignant mesothelioma and lung tumors. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 924–935.

- Poulsen, S.S.; Jackson, P.; Kling, K.; Knudsen, K.B.; Skaug, V.; Kyjovska, Z.O.; Thomsen, B.L.; Clausen, P.A.; Atluri, R.; Berthing, T.; et al. Multi-walled carbon nanotube physicochemical properties predict pulmonary inflammation and genotoxicity. Nanotoxicology 2016, 10, 1263–1275.

- Sinn, K.; Mosleh, B.; Hoda, M.A. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: Recent developments. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2021, 33, 80–86.

- Rozitis, E.; Johnson, B.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Lee, K. The Use of Immunohistochemistry, Fluorescence in situ hybridization, and emerging epigenetic markers in the diagnosis of malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM): A review. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1742.

- Ferrari, L.; Carugno, M.; Mensi, C.; Pesatori, A.C. Circulating Epigenetic biomarkers in malignant pleural mesothelioma: State of the art and critical evaluation. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 445.

- Yu, M.; Lou, J.; Xia, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Ying, S.; Zhu, L.; Liu, L.; et al. Global DNA hypomethylation has no impact on lung function or serum inflammatory and fibrosis cytokines in asbestos-exposed population. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2017, 90, 265–274.

- Yu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Lou, J.; Zhang, X. Mesothelin (MSLN) methylation and soluble mesothelin-related protein levels in a Chinese asbestos-exposed population. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2015, 20, 369–378.

- Öner, D.; Ghosh, M.; Bové, H.; Moisse, M.; Boeckx, B.; Duca, R.C.; Poels, K.; Luyts, K.; Putzeys, E.; Van Landuydt, K.; et al. Differences in MWCNT- and SWCNT-induced DNA methylation alterations in association with the nuclear deposition. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2018, 15, 11.

- Sierra, M.I.; Rubio, L.; Bayón, G.F.; Cobo, I.; Menendez, P.; Morales, P.; Mangas, C.; Urdinguio, R.G.; Lopez, V.; Valdes, A.; et al. DNA methylation changes in human lung epithelia cells exposed to multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Nanotoxicology 2017, 11, 857–870.

- Öner, D.; Ghosh, M.; Coorens, R.; Bové, H.; Moisse, M.; Lambrechts, D.; Ameloot, M.; Godderis, L.; Hoet, P.H. Induction and recovery of CpG site specific methylation changes in human bronchial cells after long-term exposure to carbon nanotubes and asbestos. Environ. Int. 2020, 137, 105530.

- Emerce, E.; Ghosh, M.; Öner, D.; Duca, R.C.; Vanoirbeek, J.; Bekaert, B.; Hoet, P.H.M.; Godderis, L. Carbon nanotube- and asbestos-induced DNA and RNA methylation changes in bronchial epithelial cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019, 32, 850–860.

- Ghosh, M.; Öner, D.; Duca, R.C.; Bekaert, B.; Vanoirbeek, J.A.; Godderis, L.; Hoet, P.H. Single-walled and multi-walled carbon nanotubes induce sequence-specific epigenetic alterations in 16 HBE cells. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 20351–20365.

- Chatterjee, N.; Yang, J.; Yoon, D.; Kim, S.; Joo, S.-W.; Choi, J. Differential crosstalk between global DNA methylation and metabolomics associated with cell type specific stress response by pristine and functionalized MWCNT. Biomaterials 2017, 115, 167–180.

- Bernholc, J.; Roland, C.; Yakobson, B.I. Nanotubes. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 1997, 2, 706–715.

- Fukushima, S.; Kasai, T.; Umeda, Y.; Ohnishi, M.; Sasaki, T.; Matsumoto, M. Carcinogenicity of multi-walled carbon nanotubes: Challenging issue on hazard assessment. J. Occup. Health 2018, 60, 10–30.

- Jiang, T.; Amadei, C.A.; Gou, N.; Lin, Y.; Lan, J.; Vecitis, C.D.; Gu, A.Z. Toxicity of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs): Effect of lengths, functional groups and electronic structures revealed by a quantitative toxicogenomics assay. Environ. Sci. Nano 2020, 7, 1348–1364.

- Ghosh, M.; Janssen, L.; Martens, D.S.; Öner, D.; Vlaanderen, J.; Pronk, A.; Kuijpers, E.; Vermeulen, R.; Nawrot, T.S.; Godderis, L.; et al. Increased telomere length and mt DNA copy number induced by multi-walled carbon nanotube exposure in the workplace. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 394, 122569.

- Sasaki, T.; Asakura, M.; Ishioka, C.; Kasai, T.; Katagiri, T.; Fukushima, S. In vitro chromosomal aberrations induced by various shapes of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs). J. Occup. Health 2016, 58, 622–631.

- Catalán, J.; Siivola, K.M.; Nymark, P.; Lindberg, H.; Suhonen, S.; Järventaus, H.; Koivisto, A.J.; Moreno, C.; Vanhala, E.; Wolff, H.; et al. In vitroandin vivogenotoxic effects of straight versus tangled multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Nanotoxicology 2016, 10, 794–806.

- Ju, L.; Wu, W.; Yu, M.; Lou, J.; Wu, H.; Yin, X.; Jia, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Zhu, L.; Yang, J. Different cellular response of human mesothelial cell met-5a to short-term and long-term multiwalled carbon nanotubes exposure. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1–10.

- García-Rodríguez, A.; Kazantseva, L.; Vila, L.; Rubio, L.; Velázquez, A.; Ramírez, M.J.; Marcos, R.; Hernández, A. Micronuclei detection by flow cytometry as a high-throughput approach for the genotoxicity testing of nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1677.

- García-Rodríguez, A.; Rubio, L.; Vila, L.; Xamena, N.; Velázquez, A.; Marcos, R.; Hernández, A. The comet assay as a tool to detect the genotoxic potential of nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1385.

- Louro, H.; Pinhão, M.; Santos, J.; Tavares, A.M.; Vital, N.; Silva, M.J. Evaluation of the cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of benchmark multi-walled carbon nanotubes in relation to their physicochemical properties. Toxicol. Lett. 2016, 262, 123–134.

- Dymacek, J.M.; Snyder-Talkington, B.N.; Raese, R.; Dong, C.; Singh, S.; Porter, D.W.; Ducatman, B.; Wolfarth, M.G.; Andrew, M.E.; Battelli, L.; et al. Similar and differential canonical pathways and biological processes associated with multiwalled carbon nanotube and asbestos-induced pulmonary fibrosis: A 1-year postexposure study. Int. J. Toxicol. 2018, 37, 276–284.

- Kasai, T.; Umeda, Y.; Ohnishi, M.; Mine, T.; Kondo, H.; Takeuchi, T.; Matsumoto, M.; Fukushima, S. Lung carcinogenicity of inhaled multi-walled carbon nanotube in rats. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2015, 13, 1–19.

- Phuyal, S.; Kasem, M.; Rubio, L.; Karlsson, H.L.; Marcos, R.; Skaug, V.; Zienolddiny, S. Effects on human bronchial epithelial cells following low-dose chronic exposure to nanomaterials: A 6-month transformation study. Toxicol. Vitr. 2017, 44, 230–240.

- Ndika, J.D.T.; Sund, J.; Alenius, H.; Puustinen, A. Elucidating differential nano-bio interactions of multi-walled andsingle-walled carbon nanotubes using subcellular proteomics. Nanotoxicology 2018, 12, 554–570.

- Ursini, C.L.; Maiello, R.; Ciervo, A.; Fresegna, A.M.; Buresti, G.; Superti, F.; Marchetti, M.; Iavicoli, S.; Cavallo, D. Evaluation of uptake, cytotoxicity and inflammatory effects in respiratory cells exposed to pristine and -OH and -COOH functionalized multi-wall carbon nanotubes. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2015, 36, 394–403.

- Nahle, S.; Cassidy, H.; Leroux, M.; Mercier, R.; Ghanbaja, J.; Doumandji, Z.; Matallanas, D.; Rihn, B.H.; Joubert, O.; Ferrari, L. Genes expression profiling of alveolar macrophages exposed to non-functionalized, anionic and cationic multi-walled carbon nanotubes shows three different mechanisms of toxicity. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 18, 1–18.

- Schubauer-Berigan, M.K.; Dahm, M.M.; Toennis, C.A.; Sammons, D.L.; Eye, T.; Kodali, V.; Zeidler-Erdely, P.C.; Erdely, A. Association of occupational exposures with ex vivo functional immune response in workers handling carbon nanotubes and nanofibers. Nanotoxicology 2020, 14, 404–419.

- Pondman, K.M.; Pednekar, L.; Paudyal, B.; Tsolaki, A.G.; Kouser, L.; Khan, H.A.; Shamji, M.H.; Haken, B.T.; Stenbeck, G.; Sim, R.B.; et al. Innate immune humoral factors, C1q and factor H, with differential pattern recognition properties, alter macrophage response to carbon nanotubes. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2015, 11, 2109–2118.

- Huaux, F.; De Bousies, V.D.; Parent, M.-A.; Orsi, M.; Uwambayinema, F.; Devosse, R.; Ibouraadaten, S.; Yakoub, Y.; Panin, N.; Palmai-Pallag, M.; et al. Mesothelioma response to carbon nanotubes is associated with an early and selective accumulation of immunosuppressive monocytic cells. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2015, 13, 1–10.

- Chen, H.; Zheng, X.; Nicholas, J.; Humes, S.T.; Loeb, J.C.; Robinson, S.E.; Bisesi, J.H., Jr.; Das, D.; Saleh, N.B.; Castleman, W.L.; et al. Single-walled carbon nanotubes modulate pulmonary immune responses and increase pandemic influenza a virus titers in mice. Virol. J. 2017, 14, 1–15.

- Park, K.H.; Chhowalla, M.; Iqbal, Z.; Sesti, F. Single-walled Carbon Nanotubes Are a New Class of Ion Channel Blockers. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 50212–50216.

- Mukherjee, S.P.; Bondarenko, O.; Kohonen, P.; Andón, F.T.; Brzicová, T.; Gessner, I.; Mathur, S.; Bottini, M.; Calligari, P.; Stella, L.; et al. Macrophage sensing of single-walled carbon nanotubes via Toll-like receptors. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–17.