Video Upload Options

In recent years, evidence has accumulated that cannabinoids—especially the non-psychoactive compound, cannabidiol (CBD)—possess promising medical and pharmacological activities that might qualify them as potential anti-tumor drugs. In this review, we elaborate on the biological effects of CBD in the anti-tumor molecular mechanism and application prospects.

1. Introduction

In the past few decades, cannabinoids—that can be classified into endogenous cannabinoids, synthetic cannabinoids and phytocannabinoids, derived from the plant Cannabis sativa L.—have attracted great interest in medicine with respect to their broad medical applicability [1]. Cannabis sativa L. has been used for the treatment of glaucoma, anxiety, nausea, depression and neuralgia [2][3][4][5]. The therapeutic value of phytocannabinoids has been demonstrated in the management of HIV/AIDS symptoms and multiple sclerosis [6][7]. Terpenoid compounds are found in the bulbous glands, capitate-sessile glands and capitate-stalked glands of pistillate flowers [8]. The capitate-stalked type glands contain the highest amount of non-psychoactive cannabinoids, whereas the well-known psychoactive compound tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA) is predominantly found in the glandular cells of the plant.

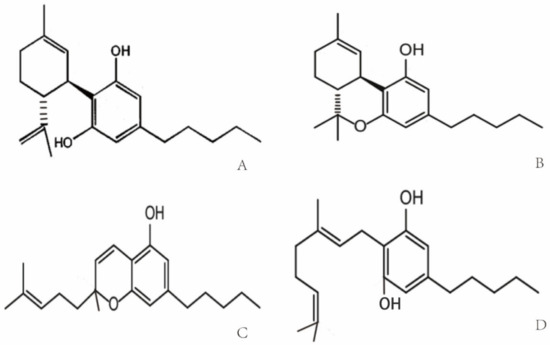

Cannabis was used for the first time for medical purposes in 16th century in Asia for analgesic, anticonvulsant, hypnotic, anti-inflammatory, antitussive and expectorant treatments [9]. In 1840, William O’Shaughnessy noted the medical properties of Indian cannabis for the treatment of different diseases including asthma, insomnia and opium-use withdrawal [10]. Due to an association of the psychoactive potential of cannabis with crime and mental deterioration, the drug was prohibited at the end of the 19th century and other non-psychoactive synthetic derivatives of cannabis have since been produced [11][12]. More than 560 different compounds have been identified in cannabis, each with different biological and chemical activities that might qualify them as potential drug candidates [13]. Phytocannabinoids that interact with the endocannabinoid system have been analyzed extensively [14]. Phytocannabinoids contain high amounts of non-psychoactive compounds such as cannabichromene (CBC), cannabigerol (CBG) and cannabidiol (CBD) [8][15], and lower amounts of psychoactive cannabinoids [16] such as Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) [8][17][18]. The chemical structures of the compounds are shown in Figure 1. Δ9-THC and CBD are the two best-studied active components of Cannabis sativa L., which can either be directly extracted from the plant or synthesized chemically for medical applications [17][19]. Clinical and preclinical trials have shown that CBD [20][21], unlike Δ9-THC, does not induce hallucinogenic effects [22]. Presently, maceration (ME), ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) and reflux heat extraction (RHE) are used to isolate phytocannabinoids such as CBD. UAE is superior to other methods with respect to time, energy consumption and costs [23]. Due to its suitable polarity, ethanol (96%) works best as the extraction solvent [24][25].

2. Molecular Targets of Cannabidiol (CBD)

CBD, one of the phytocannabinoids of Cannabis sativa L., was first identified by Raphael Mechoulam in the 1960s [27]. CBD with a molecular weight of 314.464 g/mol consists of a cyclohexene ring, a phenolic ring and a pentyl sidechain. In addition, methyl, n-propyl, n-butyl, and n-pentyl sidechain homologs are present in CBD [28][29]. The metabolism of CBD starts with a hydroxylation on position C-7, which results in (−)-7-hydroxy-CBD, followed by (−)-7-carboxy-CBD after a further oxidation step [30].

Cannabinoid receptors and other constituents of the endocannabinoid system have also been identified and characterized. Cannabinoid receptor interaction influences different physiological processes such as appetite, pain and inflammation [31][32]. Based on their molecular structure, cannabinoid receptors belong to the guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G protein)-coupled receptor superfamily [33] that stimulates guanosine 5′-O-(3-[35S]thio)-triphosphate ([35S]GTPγS) and thereby decreases the affinity of GDP binding [34][35]. The cannabinoid receptor CB1 contains seven-transmembrane domains, which initiate the mitogen-activated protein kinase via G proteins for cell signaling. The cannabinoid receptor CB2 shares a sequence homology of 48% with CB1. Cannabinoid-specific receptors are expressed on a large variety of different mammalian tissues. In contrast to CB1, CB2 is not expressed on cells of the central nervous system, but on some peripheral neuronal tissues. CB1 and CB2 are both expressed on many primary immune cells [36][37]. Δ9-THC specifically binds to both cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2. In the CB1 receptor-containing endocannabinoid system, Δ9-THC acts as an agonist, but its agonistic potency is significantly lower than that of other cannabinoids receptor agonists (e.g., CP55940 or WIN55212) with a high intrinsic activity [35][38]. The binding of Δ9-THC to the CB2 receptor is weaker than that to the CB1 receptor [39]. Unlike Δ9-THC, CBD acts as a cannabinoid receptor antagonist with low affinity to both receptors [26][40][41], whereas the isomers (+)-CBD exhibit a high affinity to CB1 and CB2 [26]. A study has shown that CBD antagonizes both cannabinoid receptors in the whole-brain membrane tissues of mice, as well as Chinese hamsters’ ovary cells which were transfected with the human CB2 receptor [42]. A few reports have now shown that CBD might act as a negative allosteric modulator of the CB1 and CB2 receptors [43][44] (Table 1).

Transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV) channels are members of the TRP superfamily that modulates the transmission of iron and calcium in cells and thereby mediates a variety of neuronal signaling processes, such as the sensing of temperature, pressure, pH, smell, etc. The occurrence of some common diseases—inflammatory and chronic pain, for instance—are associated with dysfunctional TRPV1 and TRPV2 receptors [26][45]. It is well accepted that CBD has a weak affinity to CB1 and CB2 receptors, but predominantly interacts with TRPV1 and TRPV2 receptors and the mustard oil receptor [26][45][46][47], which acts as a negative allosteric modulator of the CB1 receptor [43][48]. TRPV1 interacts with phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) signaling [49] and thereby supports cell survival. In contrast to TRPV1, TRPV2 is predominantly activated by different phytocannabinoids [50] including CBD [51]. The efficacy of CBD to activate TRPV3/4 is weaker compared to that of TRPV1/2 (~54, ~15 vs. ~78, ~67%, respectively) [52] (Table 1). CBD displays a high potency to agonistically support the TRP ankyrin type-1 (TRPA1) channel’s activity (efficacy ~108%) [52], whereas it antagonizes the TRP melastatin type-8 (TRPM8) channel’s activity [53]. Other molecular targets of CBD that are mediated through the CB1/CB2 receptors include the fatty acid neurotransmitter [54][55][56], G-protein coupled receptors (GPR55/ GPR18) [57][58][59][60], serotonin receptor 5-HT1 [61], peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) [62][63], cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) enzymes and glycine-receptor [64]. Furthermore, CBD mediates neuroprotection by influencing cytosolic Ca2+ and K+ homeostasis by blocking low-voltage-activated (T-type) Ca2+ channels [65][66], reducing Ca2+ levels, preventing Ca2+ oscillations under high-excitability and by altering K+ levels [45].

Table 1. Affinity of the receptors to CBD.

| Receptor | Effect | Affinity | Sequence Identity |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRPV1 | agonist | ~78% [52] | 79% [52] |

| TRPV2 | agonist | ~67% [52] | 96% [52] |

| TRPV3 | agonist | ~54% [52] | 77% [52] |

| TRPV4 | agonist | 15% [52] | 68% [52] |

| TRPA1 | agonist | 108% [52] | ~30% [52] |

| TRPM8 | antagonist | IC50 = 70–160 nM [53] | ~30% with TRPV2 [52] |

| CB2 | inverse agonist | Ki = 4200 nM [53] | N |

| CB1 | antagonist | Ki = 4900 nM [53] | N |

| GPR55 | antagonist | IC50 = 445 nM [67] | N |

Sequence identity, percentage of receptor sequence homology within the putative CBD binding site; N, not defined.

3. CBD and Cancer

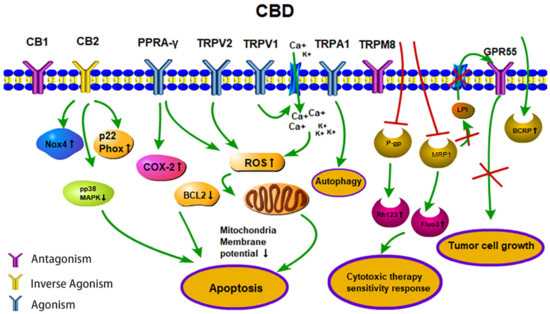

Cancer has become the second greatest cause of disease-related death worldwide in the past few decades [68]. The major treatment strategies for cancer are based on surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. However, normal tissue toxicity and the therapy resistance of tumor cells often limit the efficacy of these three major treatment pillars. Therefore, there is a great medical need for anti-cancer drugs that are well tolerated and highly effective against cancer cells. CBD could serve as a potential anti-cancer drug candidate that fulfills these criteria. In vitro studies with fetal rat telencephalon cells have revealed that highly lipophilic cannabinoids can easily cross the blood-brain barrier and thereby access tumor target cells within the nervous system [69]. Since CB2 receptors mediate neuronal cell survival and proliferation, treatment with the antagonist, CBD, could inhibit the formation and propagation of malignant glial tumor cells [37]. Lipophilic CBD influences mitochondrial calcium stores, glycine receptors and fatty amide hydrolases [70]. Due to its non-psychoactive characteristics, lipophilic CBD has the potential to become an important drug in the treatment of glioblastoma [71]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that CBD impedes tumor cell proliferation and metastatic spread and induces autophagy and/or apoptosis in tumor cells [62][72]. CBD induces tumor cell apoptosis by activating the pro-caspases-3/8/9 and increases the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in human glioma cells. In addition, CBD disturbs redox homeostasis by depleting intracellular glutathione stores via stimulation of the activity of both glutathione reductase and glutathione peroxidase. Interestingly, CBD does not influence the viability of normal primary glial cells [73]. Incubation of the human glioblastoma cell lines, U87 and U373, with CBD reduces their proliferative capacity in a concentration-dependent manner [74]. The partial activation of CB2 receptor activity by CBD is not impaired by the antagonistic activity of the CB1 receptor, and in the absence of the ROS scavenger alpha-tocopherol/vitamin E, the induction of apoptosis by CBD is not inhibited [73][74]. The treatment of leukemia cells with CBD has resulted in CB2 receptor-mediated cell death. CBD treatment results in a disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential, which is accompanied by a release of the pro-apoptotic factor cytochrome c [75]. Other studies have demonstrated that CBD affects the regulation of CB2 and the NAD(P)H oxidases Nox4 and p22 (Phox) [76]. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines (A549, H460, H358), the inhibition of the invasive capacity of the tumor cells by CBD has been related to a reduction in plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) [77]. COX-2 inhibitor (NS-298) and PPAR-γ antagonist (GW9662) studies in lung cancer cell lines (A549, H460) and primary lung cancer cells have demonstrated that CBD-induced apoptosis is associated with an upregulation of the pro-apoptotic markers, COX-2 and PPAR-γ [78]. Activation of the cannabinoid receptors by CBD induces apoptotic cell death in epidermal tumor cells in vitro and results in significant growth inhibition in an epidermal tumor mouse model. Interestingly, the viability of non-transformed normal epidermal cells remains unaffected by CBD [79] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Anti-tumor activities (apoptosis, therapy sensitivity, autophagy, tumor cell growth) of CBD. CBD acts as an agonist for the receptors TRPV1/2, TRPA1 and PPARγ. CBD acts as an inverse agonist of the receptors CB1/CB2 and as an antagonist of the receptors GPR55 and TRPM8. CBD inhibits the efflux transporters P-gp and MRP1 and thereby reverses multi-drug resistance. CBD inhibits the MRP1 pump LPI out and the autocrine loop with GPR55 thereby reduces cell proliferation. Abbreviations: BCRP, breast cancer resistance protein; BCL2, B-cell lymphoma 2; CB1/2, cannabinoid receptors type 1/2; CBD, cannabidiol; COX-2, cyclooxygenase 2; Fluo3, substrate of MRP1; GPR55, G-protein-coupled receptor 55; LPI, lysophospholipid lysophosphatidylinositol; MRP1, multidrug resistance-related protein 1; NOX4, NADPH oxidase 4; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma; P-gp, P-glycoprotein; p22 Phox, human neutrophil cytochrome b light chain; Rh123, P-gp substrate rhodamine 123; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TRPV1/2, transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1/2; TRPA1, TRP ankyrin type-1; TRPM8, TRP melastatin type-8.

Depending on the applied concentration, CBD mediates different pharmacological effects. Low CBD concentrations, in the range of 0.01 µM to 9 μM, do not impair tumor cell viability but result in an increased migratory capacity of U87 glioblastoma cells. In this low concentration range, the biological activities of CBD are neither related to the CB1/CB2 receptors nor the TRPV1 receptor [80], whereas the effects of higher CBD concentrations clearly depend on these receptors [26]. Furthermore, CBD acts as a TRPV2-selective activator by intensifying Ca2+ influx and thereby inducing apoptosis in U87 glioblastoma cells [81]. Other studies suggest that CBD may promote doxorubicin-mediated cell death in hepatocellular carcinoma (BNL1 ME) and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells by facilitating the uptake of doxorubicin, via the activation of the TRPV2 channels [82][83]. Overexpression of TRPV3 in human lung cancer cells correlates with a poor overall survival of lung cancer patients, but blocking TRPV3 efficiently inhibits the proliferation of lung cancer cells [84]. The low binding capacity of CBD to TRPV3 might be another explanation for its anti-tumoral effects. Treatment of the triple-negative breast carcinoma cell line, MDA-MB-231, with CBD induces both, autophagy and apoptosis, as demonstrated by a ROS accumulation, Beclin1 activation and Bcl-2 inhibition [85]. TRPA1/TRPM8 receptors that have been shown to promote autophagy and the metabolic transformation of UCP2 (uncoupling protein 2), respectively, in Lewis lung cancer (LLC) cells [85] might be responsible for CBD-induced autophagy and modulated ROS levels (Figure 2).

In combination with temozolomide (TMZ, the benchmark drug for the management of GBM), cannabinoids enhance autophagy in U87MG glioblastoma cells in vitro. In xenograft glioblastoma mouse models, a subsequent reduction in tumor size is associated with an increase in active cleaved caspases [86]. Treatment of U251 and SF126 glioblastoma cell lines with both Δ9-THC plus CBD is superior to monotherapy with Δ9-THC with respect to ERK signaling, G0-G1 arrest and repression of tumor cell survival [87]. Additionally, combined treatment has resulted in modulation of the oxidative stress response and the lipoxygenase pathway [80][86][87]. Ligresti et al. have reported an accumulation of intracellular Ca2+ and reactive oxygen species (ROS) upon CBD treatment, followed by an induction of apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells through either direct or indirect activation of CB2 and/or TRPV1 receptors [88]. Another study in MDA-MB-231 cells shows the induction of autophagy and apoptosis and an increase in the ER stress response, AKT/mTOR pathway and cell cycle arrest by CBD [85]. Moreover, CBD significantly inhibits EGFR/AKT and MAPK/ERK, as well as NF-kB signaling that mediates proliferation and chemotaxis [89]. CBD also inhibits some efflux transporters, such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and multidrug resistance-related protein 1 (MRP1) by reversing multiple drug resistance (MDR) in anti-cancer therapies. Decreased P-gp expression correlates with an accumulation of the P-gp substrate Rhodamine 123 (Rh123) and promotes the sensitivity of the human T lymphoblastoid leukemia cell line (CEM/VLB(100)) and a mouse fibroblast MDR1 transfected cell line (77.1) towards the P-gp substrate, vinblastine [90]. Moreover, CBD increases the uptake of intracellular MRP1 substrates, Fluo3 and vincristine in ovarian carcinoma cells [91]. Another study has shown that P-gp efflux function is down-regulated after long-term (72 h) CBD exposure, while the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP), one of the efflux transporters, is up-regulated in a choriocarcinoma cell line [92]. The MRP1 (ATP-binding cassette transporter) pump LPI (lysophospholipid lysophosphatidylinositol) initializes cascades downstream of GPR55 to induce proliferation and migration in prostate and ovarian cancer cells [93]. CBD has also been shown to inhibit GPR55-mediated migratory and proliferative capacity in breast cancer cells [94]. CBD strongly inhibits the anti-invasive capacity of tumor cells by reducing Id-1 (an inhibitor of basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors), as shown by in vitro and in vivo experiments [95][96]. The intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1), which are frequently decreased in tumor cells upon treatment, are up-regulated by CBD, whereas an opposite trend is detected for matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in lung cancer cells, which obstruct tumor cells’ ability to pass through complex extracellular matrices [97] (Table 2).

Due to their small size, targeted nanoparticles loaded with drugs show an advantageous biodistribution and dissemination in the body, and have the capacity to release the drug in close proximity to the tumor [98][99]. Although CBD is a potentially effective anti-cancer drug, poor water solubility and the requirement for organic solvents such as ethanol or methanol limit its broader application [100][101]. Due to these limitations, nanoparticles loaded with CBD (CBD-NPs) at a ratio of 1:5 or 3% (w/w) have first been tested to treat ovarian cancer cells in vitro and for in vivo models. Compared to free CBD in organic solvents, CBD-NPs induce apoptosis and tumor growth inhibition at lower IC50 values [102]. CBD in lipid nanocarriers exhibits a high brain targeting ability by enhancing the passage across the blood-brain barrier in vitro and in ovo and, therefore, might provide a novel strategy to treat CNS tumors [103].

Table 2. Studies summarizing the multiple effects of CBD.

| Type/Cancer | Cell Line | Mechanism | Conclusion | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| glioblastoma | U87/U373 in vitro/in vivo |

ssDNA↑ | proliferation↓ apoptosis |

[74] |

| prostate ovarian | PC-3/DU145 OVCAR3 |

GPR55/LPI↓ phospho ERK1/2↓ |

proliferation↓ cell migration↓ |

[93] |

| glioblastoma | U87 | ROS↑ caspase↑ cytochrome c↑ CB1/CB2/TRPV1 receptor-independent TRPV2-activation Ca2+ influx↑ |

apoptosis↑ migration↓ viability↓ (no effect at low doses) |

[73][80][81] |

| glioblastoma | U251/SF126 in vitro/in vivo |

ERK↓ G0-G1 arrest ROS↑ Id-1↓ |

cell survival↓ proliferation↓ apoptosis↑ aggressiveness↓ |

[87][95] |

| acute T lymphoblastic leukemia | Jurkat/MOLT-3/CCFR-CEM/K562/Reh/RS4 | mito Ca2+ overload mito transition pore formation↑ ROS↑ cytochrome c↑ |

autophagy↑ apoptosis↑ |

[75] |

| breast | MDA-MB-231/MCF-7 | AKT/mTOR↓ BCL2↓ ROS↑ beclin1↑ direct/indirect activation CB2 and/or TRPV1 intracellular Ca2+↑ AKT/mTOR↓ cell cycle arrest GPR55↓ LPI↓ |

apoptosis/ autophagy↑ migration↓ |

[85][94] |

| breast | SUM159/4T1/SCP2/MVT-1/MDA-MB-231/RAW 264.7 | GM-CSF/CCL3↓ NF-κB↓ EGFR/AKT↓ MAPK/ERK↓ |

cell growth↓ metastasis↓ TME |

[89] |

| lung | A549/H460/H358 in vitro/in vivo |

PAI-1↓ COX-2/PPAR-γ↑ ICAM-1↑ TIMP-1↑ MMP↓ |

invasiveness↓ apoptosis↑ |

[77][78][97] |

| T lymphoblastoid leukemia | CEM/VLB(100) | P-gp↓ Rh123↑ |

sensitivity↑ | [90] |

| ovarian | 2008 | MRP1↓ Fluo3/vincristine↑ GPR55↓ LPI↓ |

sensitivity↑ proliferation↓ |

[91][93][104] |

| immune cells | T/macrophages/NK cells | IFN-γ↓ IL-2↓ TNF-α↓ IL-10↑ GM-CSF↓ CCL3↓ NFAT↓ |

proliferation↓ infiltration↓ |

[89][105][106][107][108] |

| primary endothelial cells | HUVEC | VEGF-2/VEGFA-2↓ MMP-2/9↓ uPA↓ ET-1↓ PDGF-AA↓ CXCL16↓ ERK/Akt↓ JNK↓ |

angiogenesis↓ | [109][110] |

Abbreviations: BCRP, breast cancer resistance protein; BCL2, B-cell lymphoma 2; CB1/2, cannabinoid receptors type 1/2; CCL, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3; COX-2, cyclooxygenase 2; CXCL16, chemokine ligand 16; EGFR/AKT, epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway; ET-1, endothelin-1; Fluo3, substrate of MRP1; GPR55, G-protein-coupled receptor 55; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IL, interleukin; Id1, inhibitor of differentiation/DNA binding; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; LPI, lysophospholipid lysophosphatidylinositol; mito, mitochondrial; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; MRP, multidrug resistance-related protein; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NK, natural killer; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T-cells; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1; PDGF-AA, platelet-derived growth factor-AA; P-gp, P-glycoprotein; PPAR-γ, peroxisome proliferators activated receptor gamma; Rh123, rhodamine 123; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ssDNA, single stranded DNA; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TIMP-1, metallopeptidase inhibitor 1; TRPV1/2, transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1/2; uPA, urokinase-type plasminogen activator; VEGF-2/VEGFA-2, vascular endothelial growth factor 2 and angiopoietin 2.

References

- Bonini, S.A.; Premoli, M.; Tambaro, S.; Kumar, A.; Maccarinelli, G.; Memo, M.; Mastinu, A. Cannabis sativa: A comprehensive ethnopharmacological review of a medicinal plant with a long history. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 227, 300–315.

- Järvinen, T.; Pate, D.W.; Laine, K. Cannabinoids in the treatment of glaucoma. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002, 95, 203–220.

- Slatkin, N.E. Cannabinoids in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: Beyond prevention of acute emesis. J. Supportive Oncol. 2007, 5, 1–9.

- Chadwick, V.L.; Rohleder, C.; Koethe, D.; Leweke, F.M. Cannabinoids and the endocannabinoid system in anxiety, depression, and dysregulation of emotion in humans. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2020, 33, 20–42.

- Liang, Y.C.; Huang, C.C.; Hsu, K.S. Therapeutic potential of cannabinoids in trigeminal neuralgia. Curr. Drug Targets. CNS Neurol. Disord. 2004, 3, 507–514.

- Abrams, D.I.; Jay, C.A.; Shade, S.B.; Vizoso, H.; Reda, H.; Press, S.; Kelly, M.E.; Rowbotham, M.C.; Petersen, K.L. Cannabis in painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Neurology 2007, 68, 515–521.

- Pryce, G.; Baker, D. Emerging properties of cannabinoid medicines in management of multiple sclerosis. Trends Neurosci. 2005, 28, 272–276.

- ElSohly, M.A.; Radwan, M.M.; Gul, W.; Chandra, S.; Galal, A. Phytochemistry of Cannabis sativa L. Prog. Chem. Org. Nat. Prod. 2017, 103, 1–36.

- Zuardi, A.W. History of cannabis as a medicine: A review. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2006, 28, 153–157.

- Klumpers, L.E.; Thacker, D.L. A Brief Background on Cannabis: From Plant to Medical Indications. J. Aoac Int. 2019, 102, 412–420.

- Pisanti, S.; Bifulco, M. Modern History of Medical Cannabis: From Widespread Use to Prohibitionism and Back. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 195–198.

- Baron, E.P. Comprehensive Review of Medicinal Marijuana, Cannabinoids, and Therapeutic Implications in Medicine and Headache: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been. Headache 2015, 55, 885–916.

- Kis, B.; Ifrim, F.C.; Buda, V.; Avram, S.; Pavel, I.Z.; Antal, D.; Paunescu, V.; Dehelean, C.A.; Ardelean, F.; Diaconeasa, Z.; et al. Cannabidiol-from Plant to Human Body: A Promising Bioactive Molecule with Multi-Target Effects in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5905.

- Kumar, A.; Premoli, M.; Aria, F.; Bonini, S.A.; Maccarinelli, G.; Gianoncelli, A.; Memo, M.; Mastinu, A. Cannabimimetic plants: Are they new cannabinoidergic modulators? Planta 2019, 249, 1681–1694.

- Morales, P.; Reggio, P.H.; Jagerovic, N. An Overview on Medicinal Chemistry of Synthetic and Natural Derivatives of Cannabidiol. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 422.

- Pellati, F.; Borgonetti, V.; Brighenti, V.; Biagi, M.; Benvenuti, S.; Corsi, L. Cannabis sativa L. and Nonpsychoactive Cannabinoids: Their Chemistry and Role against Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Cancer. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1691428.

- Appendino, G.; Chianese, G.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O. Cannabinoids: Occurrence and medicinal chemistry. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 1085–1099.

- Chandra, S.; Lata, H.; ElSohly, M.A.; Walker, L.A.; Potter, D. Cannabis cultivation: Methodological issues for obtaining medical-grade product. Epilepsy Behav. EB 2017, 70, 302–312.

- Andre, C.M.; Hausman, J.F.; Guerriero, G. Cannabis sativa: The Plant of the Thousand and One Molecules. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 19.

- Husni, A.S.; McCurdy, C.R.; Radwan, M.M.; Ahmed, S.A.; Slade, D.; Ross, S.A.; ElSohly, M.A.; Cutler, S.J. Evaluation of Phytocannabinoids from High Potency Cannabis sativa using In Vitro Bioassays to Determine Structure-Activity Relationships for Cannabinoid Receptor 1 and Cannabinoid Receptor 2. Med. Chem. Res. Int. J. Rapid Commun. Des. Mech. Action Biol. Act. Agents 2014, 23, 4295–4300.

- Rong, C.; Lee, Y.; Carmona, N.E.; Cha, D.S.; Ragguett, R.M.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Mansur, R.B.; Ho, R.C.; McIntyre, R.S. Cannabidiol in medical marijuana: Research vistas and potential opportunities. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 121, 213–218.

- Boggs, D.L.; Nguyen, J.D.; Morgenson, D.; Taffe, M.A.; Ranganathan, M. Clinical and Preclinical Evidence for Functional Interactions of Cannabidiol and Δ(9)-Tetrahydrocannabinol. Neuropsychopharmacol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018, 43, 142–154.

- Baranauskaite, J.; Marksa, M.; Ivanauskas, L.; Vitkevicius, K.; Liaudanskas, M.; Skyrius, V.; Baranauskas, A. Development of extraction technique and GC/FID method for the analysis of cannabinoids in Cannabis sativa L. spp. santicha (hemp). Phytochem. Anal. 2020, 31, 516–521.

- Gul, W.; Gul, S.W.; Radwan, M.M.; Wanas, A.S.; Mehmedic, Z.; Khan, I.I.; Sharaf, M.H.M.; ElSohly, M.A. Determination of 11 Cannabinoids in Biomass and Extracts of Different Varieties of Cannabis Using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. J. Aoac Int. 2019, 98, 1523–1528.

- Brighenti, V.; Pellati, F.; Steinbach, M.; Maran, D.; Benvenuti, S. Development of a new extraction technique and HPLC method for the analysis of non-psychoactive cannabinoids in fibre-type Cannabis sativa L. (hemp). J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2017, 143, 228–236.

- Bisogno, T.; Hanus, L.; De Petrocellis, L.; Tchilibon, S.; Ponde, D.E.; Brandi, I.; Moriello, A.S.; Davis, J.B.; Mechoulam, R.; Di Marzo, V. Molecular targets for cannabidiol and its synthetic analogues: Effect on vanilloid VR1 receptors and on the cellular uptake and enzymatic hydrolysis of anandamide. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 134, 845–852.

- Pertwee, R.G. Cannabinoid pharmacology: The first 66 years. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 147 (Suppl. 1), S163–S171.

- Elsohly, M.A.; Slade, D. Chemical constituents of marijuana: The complex mixture of natural cannabinoids. Life Sci. 2005, 78, 539–548.

- Jones, P.G.; Falvello, L.; Kennard, O.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Mechoulam, R. Cannabidiol. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 1977, 33, 3211–3214.

- Agurell, S.; Halldin, M.; Lindgren, J.E.; Ohlsson, A.; Widman, M.; Gillespie, H.; Hollister, L. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of delta 1-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids with emphasis on man. Pharm. Rev. 1986, 38, 21–43.

- Wilson, R.I.; Nicoll, R.A. Endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. Science 2002, 296, 678–682.

- Klein, T.W. Cannabinoid-based drugs as anti-inflammatory therapeutics. Nat. Reviews. Immunol. 2005, 5, 400–411.

- Munro, S.; Thomas, K.L.; Abu-Shaar, M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature 1993, 365, 61–65.

- Griffin, G.; Atkinson, P.J.; Showalter, V.M.; Martin, B.R.; Abood, M.E. Evaluation of cannabinoid receptor agonists and antagonists using the guanosine-5′-O-(3-35Sthio)-triphosphate binding assay in rat cerebellar membranes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998, 285, 553–560.

- Breivogel, C.S.; Selley, D.E.; Childers, S.R. Cannabinoid Receptor Agonist Efficacy for Stimulating 35SGTPγS Binding to Rat Cerebellar Membranes Correlates with Agonist-induced Decreases in GDP Affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 16865–16873.

- Howlett, A.C.; Barth, F.; Bonner, T.I.; Cabral, G.; Casellas, P.; Devane, W.A.; Felder, C.C.; Herkenham, M.; Mackie, K.; Martin, B.R.; et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXVII. Classification of Cannabinoid Receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2002, 54, 161.

- Fernández-Ruiz, J.; Romero, J.; Velasco, G.; Tolón, R.M.; Ramos, J.A.; Guzmán, M. Cannabinoid CB2 receptor: A new target for controlling neural cell survival? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2007, 28, 39–45.

- Pertwee, R.G. Pharmacology of cannabinoid receptor ligands. Curr. Med. Chem. 1999, 6, 635–664.

- Bayewitch, M.; Rhee, M.-H.; Avidor-Reiss, T.; Breuer, A.; Mechoulam, R.; Vogel, Z. (—)-Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol Antagonizes the Peripheral Cannabinoid Receptor-mediated Inhibition of Adenylyl Cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 9902–9905.

- Pertwee, R.G. The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and delta9-tetrahydrocannabivarin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 153, 199–215.

- Pertwee, R.G.; Ross, R.A. Cannabinoid receptors and their ligands. Prostaglandinsleukotrienesand Essent. Fat. Acids 2002, 66, 101–121.

- Thomas, A.; Baillie, G.L.; Phillips, A.M.; Razdan, R.K.; Ross, R.A.; Pertwee, R.G. Cannabidiol displays unexpectedly high potency as an antagonist of CB1 and CB2 receptor agonists in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 150, 613–623.

- Laprairie, R.B.; Bagher, A.M.; Kelly, M.E.; Denovan-Wright, E.M. Cannabidiol is a negative allosteric modulator of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 4790–4805.

- Martínez-Pinilla, E.; Varani, K.; Reyes-Resina, I.; Angelats, E.; Vincenzi, F.; Ferreiro-Vera, C.; Oyarzabal, J.; Canela, E.I.; Lanciego, J.L.; Nadal, X.; et al. Binding and Signaling Studies Disclose a Potential Allosteric Site for Cannabidiol in Cannabinoid CB(2) Receptors. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 744.

- De Petrocellis, L.; Ligresti, A.; Moriello, A.S.; Allarà, M.; Bisogno, T.; Petrosino, S.; Stott, C.G.; Di Marzo, V. Effects of cannabinoids and cannabinoid-enriched Cannabis extracts on TRP channels and endocannabinoid metabolic enzymes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 1479–1494.

- Vandewauw, I.; De Clercq, K.; Mulier, M.; Held, K.; Pinto, S.; Van Ranst, N.; Segal, A.; Voet, T.; Vennekens, R.; Zimmermann, K.; et al. A TRP channel trio mediates acute noxious heat sensing. Nature 2018, 555, 662–666.

- De Petrocellis, L.; Nabissi, M.; Santoni, G.; Ligresti, A. Actions and Regulation of Ionotropic Cannabinoid Receptors. Adv. Pharmacol. 2017, 80, 249–289.

- Hill, T.D.; Cascio, M.G.; Romano, B.; Duncan, M.; Pertwee, R.G.; Williams, C.M.; Whalley, B.J.; Hill, A.J. Cannabidivarin-rich cannabis extracts are anticonvulsant in mouse and rat via a CB1 receptor-independent mechanism. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 170, 679–692.

- Nilius, B.; Szallasi, A. Transient receptor potential channels as drug targets: From the science of basic research to the art of medicine. Pharm. Rev. 2014, 66, 676–814.

- Soethoudt, M.; Grether, U.; Fingerle, J.; Grim, T.W.; Fezza, F.; de Petrocellis, L.; Ullmer, C.; Rothenhäusler, B.; Perret, C.; van Gils, N.; et al. Cannabinoid CB(2) receptor ligand profiling reveals biased signalling and off-target activity. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 13958.

- Qin, N.; Neeper, M.P.; Liu, Y.; Hutchinson, T.L.; Lubin, M.L.; Flores, C.M. TRPV2 is activated by cannabidiol and mediates CGRP release in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 6231–6238.

- Muller, C.; Reggio, P.H. An Analysis of the Putative CBD Binding Site in the Ionotropic Cannabinoid Receptors. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 615811.

- De Petrocellis, L.; Vellani, V.; Schiano-Moriello, A.; Marini, P.; Magherini, P.C.; Orlando, P.; Di Marzo, V. Plant-derived cannabinoids modulate the activity of transient receptor potential channels of ankyrin type-1 and melastatin type-8. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 325, 1007–1015.

- Elmes, M.W.; Kaczocha, M.; Berger, W.T.; Leung, K.; Ralph, B.P.; Wang, L.; Sweeney, J.M.; Miyauchi, J.T.; Tsirka, S.E.; Ojima, I.; et al. Fatty Acid-binding Proteins (FABPs) Are Intracellular Carriers for Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and Cannabidiol (CBD). J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 8711–8721.

- Di Marzo, V. Targeting the endocannabinoid system: To enhance or reduce? Nat. Reviews. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 438–455.

- Oesch, S.; Gertsch, J. Cannabinoid receptor ligands as potential anticancer agents--high hopes for new therapies? J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2009, 61, 839–853.

- Ohlsson, A.; Lindgren, J.-E.; Andersson, S.; Agurell, S.; Gillespie, H.; Hollister, L.E. Single-dose kinetics of deuterium-labelled cannabidiol in man after smoking and intravenous administration. Biomed. Environ. Mass Spectrom. 1986, 13, 77–83.

- Fernández-Ruiz, J.; Sagredo, O.; Pazos, M.R.; García, C.; Pertwee, R.; Mechoulam, R.; Martínez-Orgado, J. Cannabidiol for neurodegenerative disorders: Important new clinical applications for this phytocannabinoid? Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 75, 323–333.

- De Petrocellis, L.; Di Marzo, V. Non-CB1, non-CB2 receptors for endocannabinoids, plant cannabinoids, and synthetic cannabimimetics: Focus on G-protein-coupled receptors and transient receptor potential channels. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. Off. J. Soc. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2010, 5, 103–121.

- Ross, R.A. The enigmatic pharmacology of GPR55. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009, 30, 156–163.

- Russo, E.B.; Burnett, A.; Hall, B.; Parker, K.K. Agonistic properties of cannabidiol at 5-HT1a receptors. Neurochem. Res. 2005, 30, 1037–1043.

- O’Sullivan, S.E.; Sun, Y.; Bennett, A.J.; Randall, M.D.; Kendall, D.A. Time-dependent vascular actions of cannabidiol in the rat aorta. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 612, 61–68.

- Spelman, K.; Iiams-Hauser, K.; Cech, N.B.; Taylor, E.W.; Smirnoff, N.; Wenner, C.A. Role for PPARgamma in IL-2 inhibition in T cells by Echinacea-derived undeca-2E-ene-8,10-diynoic acid isobutylamide. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2009, 9, 1260–1264.

- Ahrens, J.; Demir, R.; Leuwer, M.; de la Roche, J.; Krampfl, K.; Foadi, N.; Karst, M.; Haeseler, G. The nonpsychotropic cannabinoid cannabidiol modulates and directly activates alpha-1 and alpha-1-Beta glycine receptor function. Pharmacology 2009, 83, 217–222.

- Izzo, A.A.; Borrelli, F.; Capasso, R.; Di Marzo, V.; Mechoulam, R. Non-psychotropic plant cannabinoids: New therapeutic opportunities from an ancient herb. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009, 30, 515–527.

- Ross, H.R.; Napier, I.; Connor, M. Inhibition of recombinant human T-type calcium channels by Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 16124–16134.

- Whyte, L.S.; Ryberg, E.; Sims, N.A.; Ridge, S.A.; Mackie, K.; Greasley, P.J.; Ross, R.A.; Rogers, M.J. The putative cannabinoid receptor GPR55 affects osteoclast function in vitro and bone mass in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 16511–16516.

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 7–30.

- Cabral, G.A.; Jamerson, M. Marijuana use and brain immune mechanisms. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2014, 118, 199–230.

- Zhornitsky, S.; Potvin, S. Cannabidiol in humans-the quest for therapeutic targets. Pharmaceuticals 2012, 5, 529–552.

- Dumitru, C.A.; Sandalcioglu, I.E.; Karsak, M. Cannabinoids in Glioblastoma Therapy: New Applications for Old Drugs. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 159.

- Zhang, X.; Qin, Y.; Pan, Z.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Qu, G.; Zhou, L.; Xu, M.; Zheng, Q.; et al. Cannabidiol Induces Cell Cycle Arrest and Cell Apoptosis in Human Gastric Cancer SGC-7901 Cells. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 302.

- Massi, P.; Vaccani, A.; Bianchessi, S.; Costa, B.; Macchi, P.; Parolaro, D. The non-psychoactive cannabidiol triggers caspase activation and oxidative stress in human glioma cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2006, 63, 2057–2066.

- Massi, P.; Vaccani, A.; Ceruti, S.; Colombo, A.; Abbracchio, M.P.; Parolaro, D. Antitumor effects of cannabidiol, a nonpsychoactive cannabinoid, on human glioma cell lines. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 308, 838–845.

- Olivas-Aguirre, M.; Torres-López, L.; Valle-Reyes, J.S.; Hernández-Cruz, A.; Pottosin, I.; Dobrovinskaya, O. Cannabidiol directly targets mitochondria and disturbs calcium homeostasis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 779.

- McKallip, R.J.; Jia, W.; Schlomer, J.; Warren, J.W.; Nagarkatti, P.S.; Nagarkatti, M. Cannabidiol-induced apoptosis in human leukemia cells: A novel role of cannabidiol in the regulation of p22phox and Nox4 expression. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 70, 897–908.

- Ramer, R.; Rohde, A.; Merkord, J.; Rohde, H.; Hinz, B. Decrease of Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 May Contribute to the Anti-Invasive Action of Cannabidiol on Human Lung Cancer Cells. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 2162–2174.

- Ramer, R.; Heinemann, K.; Merkord, J.; Rohde, H.; Salamon, A.; Linnebacher, M.; Hinz, B. COX-2 and PPAR-γ confer cannabidiol-induced apoptosis of human lung cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013, 12, 69–82.

- Casanova, M.L.; Blázquez, C.; Martínez-Palacio, J.; Villanueva, C.; Fernández-Aceñero, M.J.; Huffman, J.W.; Jorcano, J.L.; Guzmán, M. Inhibition of skin tumor growth and angiogenesis in vivo by activation of cannabinoid receptors. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 43–50, (0021-9738 (Print)).

- Vaccani, A.; Massi, P.; Colombo, A.; Rubino, T.; Parolaro, D. Cannabidiol inhibits human glioma cell migration through a cannabinoid receptor-independent mechanism. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 144, 1032–1036.

- Nabissi, M.; Morelli, M.B.; Santoni, M.; Santoni, G. Triggering of the TRPV2 channel by cannabidiol sensitizes glioblastoma cells to cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents. Carcinogenesis 2012, 34, 48–57.

- Neumann-Raizel, H.; Shilo, A.; Lev, S.; Mogilevsky, M.; Katz, B.; Shneor, D.; Shaul, Y.D.; Leffler, A.; Gabizon, A.; Karni, R.; et al. 2-APB and CBD-Mediated Targeting of Charged Cytotoxic Compounds Into Tumor Cells Suggests the Involvement of TRPV2 Channels. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1198.

- Elbaz, M.; Ahirwar, D.; Xiaoli, Z.; Zhou, X.; Lustberg, M.; Nasser, M.W.; Shilo, K.; Ganju, R.K. TRPV2 is a novel biomarker and therapeutic target in triple negative breast cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 33459–33470.

- Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, K.; Li, B.; Li, H.; Qi, H.; Guo, J.; Cao, Y.; Sun, H. Overexpression of TRPV3 Correlates with Tumor Progression in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 437.

- Shrivastava, A.; Kuzontkoski, P.M.; Groopman, J.E.; Prasad, A. Cannabidiol induces programmed cell death in breast cancer cells by coordinating the cross-talk between apoptosis and autophagy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011, 10, 1161–1172.

- Torres, S.; Lorente, M.; Rodríguez-Fornés, F.; Hernández-Tiedra, S.; Salazar, M.; García-Taboada, E.; Barcia, J.; Guzmán, M.; Velasco, G. A combined preclinical therapy of cannabinoids and temozolomide against glioma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011, 10, 90–103, (1538-8514 (Electronic)).

- Marcu, J.P.; Christian, R.T.; Lau, D.; Zielinski, A.J.; Horowitz, M.P.; Lee, J.; Pakdel, A.; Allison, J.; Limbad, C.; Moore, D.H.; et al. Cannabidiol enhances the inhibitory effects of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol on human glioblastoma cell proliferation and survival. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010, 9, 180–189, (1538-8514 (Electronic)).

- Ligresti, A.; Moriello, A.S.; Starowicz, K.; Matias, I.; Pisanti, S.; De Petrocellis, L.; Laezza, C.; Portella, G.; Bifulco, M.; Di Marzo, V. Antitumor activity of plant cannabinoids with emphasis on the effect of cannabidiol on human breast carcinoma. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 318, 1375–1387.

- Elbaz, M.; Nasser, M.W.; Ravi, J.; Wani, N.A.; Ahirwar, D.K.; Zhao, H.; Oghumu, S.; Satoskar, A.R.; Shilo, K.; Carson, W.E., 3rd; et al. Modulation of the tumor microenvironment and inhibition of EGF/EGFR pathway: Novel anti-tumor mechanisms of Cannabidiol in breast cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2015, 9, 906–919.

- Holland, M.L.; Panetta, J.A.; Hoskins, J.M.; Bebawy, M.; Roufogalis, B.D.; Allen, J.D.; Arnold, J.C. The effects of cannabinoids on P-glycoprotein transport and expression in multidrug resistant cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 71, 1146–1154.

- Holland, M.L.; Allen, J.D.; Arnold, J.C. Interaction of plant cannabinoids with the multidrug transporter ABCC1 (MRP1). Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 591, 128–131.

- Feinshtein, V.; Erez, O.; Ben-Zvi, Z.; Erez, N.; Eshkoli, T.; Sheizaf, B.; Sheiner, E.; Huleihel, M.; Holcberg, G. Cannabidiol changes P-gp and BCRP expression in trophoblast cell lines. PeerJ 2013, 1, e153.

- Piñeiro, R.; Maffucci, T.; Falasca, M. The putative cannabinoid receptor GPR55 defines a novel autocrine loop in cancer cell proliferation. Oncogene 2011, 30, 142–152.

- Ford, L.A.; Roelofs, A.J.; Anavi-Goffer, S.; Mowat, L.; Simpson, D.G.; Irving, A.J.; Rogers, M.J.; Rajnicek, A.M.; Ross, R.A. A role for L-alpha-lysophosphatidylinositol and GPR55 in the modulation of migration, orientation and polarization of human breast cancer cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 160, 762–771.

- Soroceanu, L.; Murase, R.; Limbad, C.; Singer, E.; Allison, J.; Adrados, I.; Kawamura, R.; Pakdel, A.; Fukuyo, Y.; Nguyen, D.; et al. Id-1 is a key transcriptional regulator of glioblastoma aggressiveness and a novel therapeutic target. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 1559–1569.

- Swarbrick, A.; Roy, E.; Allen, T.; Bishop, J.M. Id1 cooperates with oncogenic Ras to induce metastatic mammary carcinoma by subversion of the cellular senescence response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 5402–5407.

- Ramer, R.; Bublitz, K.; Freimuth, N.; Merkord, J.; Rohde, H.; Haustein, M.; Borchert, P.; Schmuhl, E.; Linnebacher, M.; Hinz, B. Cannabidiol inhibits lung cancer cell invasion and metastasis via intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Faseb J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2012, 26, 1535–1548.

- Cheng, C.J.; Tietjen, G.T.; Saucier-Sawyer, J.K.; Saltzman, W.M. A holistic approach to targeting disease with polymeric nanoparticles. Nat. Reviews. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 239–247.

- Deng, Y.; Yang, F.; Cocco, E.; Song, E.; Zhang, J.; Cui, J.; Mohideen, M.; Bellone, S.; Santin, A.D.; Saltzman, W.M. Improved i.p. drug delivery with bioadhesive nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 11453.

- Fraguas-Sánchez, A.I.; Fernández-Carballido, A.; Simancas-Herbada, R.; Martin-Sabroso, C.; Torres-Suárez, A.I. CBD loaded microparticles as a potential formulation to improve paclitaxel and doxorubicin-based chemotherapy in breast cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 574, 118916.

- Viudez-Martínez, A.; García-Gutiérrez, M.S.; Navarrón, C.M.; Morales-Calero, M.I.; Navarrete, F.; Torres-Suárez, A.I.; Manzanares, J. Cannabidiol reduces ethanol consumption, motivation and relapse in mice. Addict. Biol. 2018, 23, 154–164.

- Fraguas-Sánchez, A.I.; Torres-Suárez, A.I.; Cohen, M.; Delie, F.; Bastida-Ruiz, D.; Yart, L.; Martin-Sabroso, C.; Fernández-Carballido, A. PLGA nanoparticles for the intraperitoneal administration of CBD in the treatment of ovarian cancer: In Vitro and In Ovo assessment. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 439.

- Aparicio-Blanco, J.; Romero, I.A.; Male, D.K.; Slowing, K.; García-García, L.; Torres-Suárez, A.I. Cannabidiol enhances the passage of lipid nanocapsules across the blood–brain barrier both in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 1999–2010.

- Malfait, A.M.; Gallily, R.; Sumariwalla, P.F.; Malik, A.S.; Andreakos, E.; Mechoulam, R.; Feldmann, M. The nonpsychoactive cannabis constituent cannabidiol is an oral anti-arthritic therapeutic in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 9561–9566.

- Liu, D.Z.; Hu, C.M.; Huang, C.H.; Wey, S.P.; Jan, T.R. Cannabidiol attenuates delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions via suppressing T-cell and macrophage reactivity. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2010, 31, 1611–1617.

- Kaplan, B.L.; Springs, A.E.; Kaminski, N.E. The profile of immune modulation by cannabidiol (CBD) involves deregulation of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT). Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008, 76, 726–737.

- Abbas, A.K.; Trotta, E.; D, R.S.; Marson, A.; Bluestone, J.A. Revisiting IL-2: Biology and therapeutic prospects. Sci. Immunol. 2018, 3.

- Frey, K.; Schliemann, C.; Schwager, K.; Giavazzi, R.; Johannsen, M.; Neri, D. The immunocytokine F8-IL2 improves the therapeutic performance of sunitinib in a mouse model of renal cell carcinoma. J. Urol. 2010, 184, 2540–2548.

- Solinas, M.; Massi, P.; Cantelmo, A.R.; Cattaneo, M.G.; Cammarota, R.; Bartolini, D.; Cinquina, V.; Valenti, M.; Vicentini, L.M.; Noonan, D.M.; et al. Cannabidiol inhibits angiogenesis by multiple mechanisms. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 167, 1218–1231.

- Pisanti, S.; Picardi, P.; Prota, L.; Proto, M.C.; Laezza, C.; McGuire, P.G.; Morbidelli, L.; Gazzerro, P.; Ziche, M.; Das, A. Genetic and pharmacologic inactivation of cannabinoid CB1 receptor inhibits angiogenesis. Blood 2011, 117, 5541–5550.