| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jeremy Hoffman | + 1673 word(s) | 1673 | 2021-04-13 06:16:16 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 1673 | 2021-04-23 08:45:37 | | |

Video Upload Options

Mycotic or fungal keratitis (FK) is a sight-threatening infection of the cornea by filamentous fungi or yeasts.

1. Introduction

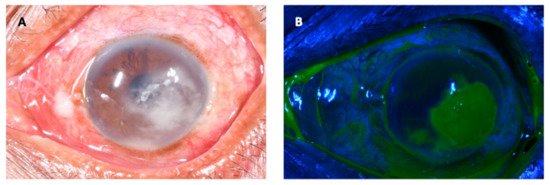

Mycotic or fungal keratitis (FK) is a severe and potentially blinding infection of the cornea (Figure 1) and is considered an ophthalmic emergency [1][2]. It is one of the leading causes of microbial keratitis (MK) or corneal ulcer. The latest conservative estimates predict that there are close to 1.5 million new infections every year [3], which correlate with estimates published more than 20 years ago [4][5]. The burden of FK is greatest in tropical and subtropical countries, accounting for between 20 and 60% of MK cases presenting in tropical regions [6], likely a result of climate (higher temperatures and relative humidity) and frequent agriculture-related ocular trauma [7].

Figure 1. Fungal keratitis in a patient presenting to an ophthalmic hospital in Nepal. The causative organism was confirmed to be Fusarium sp. on culture. (A): The conjunctiva is hyperaemic, causing the eye to be red. There is a white corneal infiltrate with feathery serrated margins and satellite lesions present. There is also a small hypopyon. (B): The same eye as viewed with a cobalt blue filter after instillation of topical fluorescein. The area staining in green represents a defect in the corneal epithelium.

Fungal keratitis is caused by yeasts and filamentous fungi but the pattern of infection varies globally with respect to aetiology and predisposing risk factors relating to geographical location and occupational exposure. Infections due to Candida spp. and other yeasts are typically associated with steroid use, ocular surface disorders, previous ocular surgery, contact lens wear and underlying illness resulting in immuno-incompetency [8], mostly occurring in temperate climes. However, the main burden of disease globally is attributable to the filamentous fungi and these infections predominantly affect the poorest patients in warm, humid, tropical climatic regions [7]. There have also been reports of an increase in Fusarium-related keratitis in contact lens wearers in temperate, industrialised regions [9][10][11]. Interestingly, even within developed countries fungal keratitis is a disease of poverty: infections are associated with contact lens wearers from deprived or low socioeconomic backgrounds [3][12].

2. Risk Factors

There are numerous risk factors for developing fungal keratitis, some attributable to the individual such as age, gender or pre-existing ophthalmic or systemic disease, with others dependent on extrinsic factors including the income status of the patient, occupation, contact-lens use, previous ocular surgery and region.

2.1. Age and Gender

Despite age and gender not being independent risk factors for fungal keratitis, they both affect other risk factors such as trauma, which is more common in younger men who tend to be agricultural labourers [12][13]. It is also important to note that older patients tend to have a more severe disease and worse outcome [14]. Furthermore, older patients are more likely to have predisposing systemic and ocular co-morbidities such as diabetes mellitus and ocular surface disease [14]. Patients between the ages of 20–40 make up the majority of cases [12][15][16][13]. In areas of high incidence of fungal keratitis such as south India, the majority of young patients (aged between 21 and 50) typically have fungal keratitis, compared to the majority of patients over 50 years old who typically have bacterial keratitis [17].

In SSA and India where the burden of FK is greatest, the majority of cases of fungal keratitis are reported in males [12][18][16]. Interestingly, one study from Nepal reports a higher proportion of females compared to males [19], whilst other studies from Nepal report male preponderance [20][21]. The reason for this difference is unclear; it may be due to different socioeconomic factors, health seeking behaviour or differing study methodology. In Europe and North America, there is considerable variation in the reported proportion of men with fungal keratitis [15][22].

2.2. Trauma

Preceding ocular trauma is a key predisposing risk factor for the development of fungal keratitis, regardless of geographical region. This is particularly true for trauma with vegetative material and trauma occurring during agricultural practices. Injury to the eye allows for a disruption to the corneal epithelium, permitting fungal pathogens to infiltrate the cornea [23][24][17][25][26][27]. Furthermore, injury with plant matter can lead to direct inoculation with fungal conidia. For regions where a fungal aetiology is the most common form of microbial keratitis such as South Asia and SSA, the reported rates of trauma range from 24 to 83% [1][28].

2.3. Occupation

Given the clear risk that trauma, particularly with organic material, poses to the cornea it is not surprising that occupations that carry a high risk of occupational ocular injury are associated with developing fungal keratitis. In particular, agricultural labourers and subsistence farmers are the most likely to develop fungal keratitis, reported to be between 56–74% of cases from studies in Nepal and India [12][20].

2.4. Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is of increasing public health concern globally, with the incidence increasing at an alarming rate in LMICs [29]. It is well-established that patients with DM are at an elevated risk of developing fungal infections [30], and DM is the most important systemic risk factor for developing fungal keratitis [31]. DM has also been shown to be an independent risk factor for the severity of fungal keratitis [32]. It is thought that hyperglycaemia can alter the ocular surface microenvironment including changes to the commensal organisms and enzyme action, allowing easier fungal adherence, proliferation and corneal penetration [32]. The associated reduced immune response seen in diabetes is also likely to be a significant factor in increasing host susceptibility to fungal infection [33].

2.5. HIV

There have been a number of studies from SSA that have suggested an association between HIV infection and fungal keratitis, following a number of case reports of fungal keratitis in AIDS patients at the start of the HIV/AIDS pandemic [34][35]. A prospective study from Tanzania in 1999 found that 81% of the patients with fungal keratitis were HIV positive, compared to only 33% in non-fungal cases (p < 0.001) [36]. Another study from Tanzania a few years later found the prevalence of HIV infection amongst MK cases to be double that of the wider population [1], although this did not directly compare the proportion of HIV positive fungal MK cases to bacterial MK cases. A more recent, nested case control study from Uganda where over 60% of MK cases were fungal, found a strong association between HIV infection and MK (OR 83.5, p = 0.02) [33][37]. There have been no studies to date looking at this association outside of SSA.

2.6. Traditional Eye Medicine

The use of traditional eye medicine (TEM) to treat a wide range of eye problems is commonplace in LMICs [38][39]. Most TEM contain non-sterile preparations comprising plant matter, often herbs or dried leaves, and are therefore a potential route for inoculating the cornea with microorganisms, particularly fungal pathogens [31]. Although there are no studies that have specifically looked at TEM as a risk factor for fungal keratitis, it has been found to be an independent risk factor in developing microbial keratitis in Tanzania and Uganda [40][33][37], where a fungal aetiology make up the majority of MK cases.

2.7. Topical Corticosteroids

It is well established that glucocorticoids are associated with an increased risk of invasive fungal infection due to the dysregulation of the patient’s immunity [41]. This holds true for prior topical steroid use, which is an independent risk factor for developing fungal keratitis [42]. Prior topical corticosteroid use is also associated with deeper corneal penetration and a worse clinical outcome [43]. Although topical corticosteroid use is associated with both yeast and filamentous fungal infections, it may be a stronger risk factor for yeast infection [15].

2.8. Ocular Surface Disease

Pre-existing ocular surface disease (OSD, a diverse range of disorders that lead to an abnormal ocular surface such as dry eye disease, corneal exposure, blepharitis, persistent epithelial defects or ocular surface inflammatory conditions) compromises the corneal epithelium and therefore allows fungal pathogens to invade the cornea. Furthermore, these conditions are often treated with topical corticosteroids or bandage contact lenses, which further increases the risk of developing fungal keratitis. Although OSD is more often associated with yeast infection [15], it remains a risk factor for filamentous fungal infection: a multi-centre study from the US found 29% of cases of fungal keratitis were associated with OSD, 42.6% of which were filamentous and 53.1% were yeast [44]. Cases of fungal keratitis with pre-existing OSD are less frequently reported in LMICs than in developed countries, other than in areas such as Tanzania, where OSD due to trachoma exists [45].

2.9. Contact Lens Usage

In industrialised countries, contact lens use constitutes the main predisposing factor for developing fungal keratitis, with studies showing between 37% and 67% of fungal cases were contact lens wearers [15][46][44]. It is important to consider, however, that it is not simply the contact lens wear itself that carries the risk-it is the type of lens used, the frequency of replacement and how the lenses are cleaned-and with what. For example, the global outbreak of Fusarium keratitis between 2005–2006 was caused by a specific contact lens cleaning solution [47]. The current proportion of patients with fungal keratitis in LMICs associated with contact lens usage is low, but this is likely to increase as these countries industrialise leading to an increased number of contact lens wearers and fewer people involved in manual agricultural labour.

2.10. Previous Ocular Surgery

A prior history of ocular surgery, including cataract, laser-refractive or corneal transplantation surgery, has been associated with the development of fungal keratitis in both developed and lower-middle income countries [48][49]. Yeasts are often the most commonly implicated pathogen following surgery [8]; for example, in a study from Boston, USA, yeasts accounted for 67% of post-surgical fungal infections. Of note, this group of patients had the worst outcome in terms of final visual acuity. In this study, all surgeries were a form of corneal transplantation [50]. However, it should be noted that prior ocular surgery is more likely to be a stronger risk factor for bacterial, rather than fungal, keratitis [51]; a study from Brazil found 32% of bacterial keratitis cases were associated with previous ocular surgery, compared to just 8% of fungal keratitis cases [52].

Despite intravitreal injections for retinal disease becoming the most commonly performed intraocular procedure globally [53], and corticosteroid periocular injections being used routinely for the treatment of diabetic macular oedema [54][55], there have been no cases of fungal keratitis associated with this treatment reported in the scientific literature to date. However, other complicating local fungal infections have been reported, including fungal endophthalmitis, fungal orbital abscesses and conjunctival mycetoma [56][57][58].

References

- Burton, M.J.; Pithuwa, J.; Okello, E.; Afwamba, I.; Onyango, J.J.; Oates, F.; Chevallier, C.; Hall, A.B. Microbial Keratitis in East Africa: Why are the Outcomes so Poor? Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2011, 18, 158–163.

- Thomas, P.A.; Leck, A.K.; Myatt, M. Characteristic clinical features as an aid to the diagnosis of suppurative keratitis caused by filamentous fungi. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 89, 1554–1558.

- Brown, L.; Leck, A.K.; Gichangi, M.; Burton, M.J.; Denning, D.W. The global incidence and diagnosis of fungal keratitis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020.

- Srinivasan, M.; Gonzales, C.A.; George, C.; Cevallos, V.; Mascarenhas, J.M.; Asokan, B.; Wilkins, J.; Smolin, G.; Whitcher, J.P. Epidemiology and aetiological diagnosis of corneal ulceration in Madurai, south India. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1997, 81, 965–971.

- Whitcher, J.P.; Srinivasan, M.; Upadhyay, M.P. Corneal blindness: A global perspective. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 214–221.

- Bongomin, F.; Gago, S.; Oladele, R.O.; Denning, D.W. Global and Multi-National Prevalence of Fungal Diseases-Estimate Precision. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 57.

- Leck, A.K.; Thomas, P.A.; Hagan, M.; Kaliamurthy, J.; Ackuaku, E.; John, M.; Newman, M.J.; Codjoe, F.S.; Opintan, J.A.; Kalavathy, C.M.; et al. Aetiology of suppurative corneal ulcers in Ghana and south India, and epidemiology of fungal keratitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 86, 1211–1215.

- Qiao, G.L.; Ling, J.; Wong, T.; Yeung, S.N.; Iovieno, A. Candida Keratitis: Epidemiology, Management, and Clinical Outcomes. Cornea 2020, 39, 801–805.

- Ahearn, D.G.; Zhang, S.; Stulting, R.D.; Schwam, B.L.; Simmons, R.B.; Ward, M.A.; Pierce, G.E.; Crow, S.A., Jr. Fusarium keratitis and contact lens wear: Facts and speculations. Med. Mycol. 2008, 46, 397–410.

- Walther, G.; Stasch, S.; Kaerger, K.; Hamprecht, A.; Roth, M.; Cornely, O.A.; Geerling, G.; Mackenzie, C.R.; Kurzai, O.; von Lilienfeld-Toal, M. Fusarium Keratitis in Germany. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 2983–2995.

- Oliveira Dos Santos, C.; Kolwijck, E.; van Rooij, J.; Stoutenbeek, R.; Visser, N.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Santana, N.T.Y.; Verweij, P.E.; Eggink, C.A. Epidemiology and Clinical Management of Fusarium keratitis in the Netherlands, 2005–2016. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 133.

- Deorukhkar, S.; Katiyar, R.; Saini, S. Epidemiological features and laboratory results of bacterial and fungal keratitis: A five-year study at a rural tertiary-care hospital in western Maharashtra, India. Singap. Med. J. 2012, 53, 264–267.

- Bharathi, M.J.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Vasu, S.; Meenakshi, R.; Palaniappan, R. Epidemiological characteristics and laboratory diagnosis of fungal keratitis. A three-year study. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 51, 315–321.

- Van der Meulen, I.J.; van Rooij, J.; Nieuwendaal, C.P.; Van Cleijnenbreugel, H.; Geerards, A.J.; Remeijer, L. Age-related risk factors, culture outcomes, and prognosis in patients admitted with infectious keratitis to two Dutch tertiary referral centers. Cornea 2008, 27, 539–544.

- Ong, H.S.; Fung, S.S.M.; Macleod, D.; Dart, J.K.G.; Tuft, S.J.; Burton, M.J. Altered Patterns of Fungal Keratitis at a London Ophthalmic Referral Hospital: An Eight-Year Retrospective Observational Study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 168, 227–236.

- Gopinathan, U.; Garg, P.; Fernandes, M.; Sharma, S.; Athmanathan, S.; Rao, G.N. The epidemiological features and laboratory results of fungal keratitis: A 10-year review at a referral eye care center in South India. Cornea 2002, 21, 555–559.

- Bharathi, M.J.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Meenakshi, R.; Padmavathy, S.; Shivakumar, C.; Srinivasan, M. Microbial Keratitis in South India: Influence of Risk Factors, Climate, and Geographical Variation. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007, 14, 61–69.

- Kibret, T.; Bitew, A. Fungal keratitis in patients with corneal ulcer attending Minilik II Memorial Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016, 16, 148.

- Suwal, S.; Bhandari, D.; Thapa, P.; Shrestha, M.; Amatya, J. Microbiological profile of corneal ulcer cases diagnosed in a tertiary care ophthalmological institute in Nepal. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016, 16.

- Ganguly, S.; Kansakar, I.; Sharma, M.; Bastola, P.; Pradhan, R. Pattern of fungal isolates in cases of corneal ulcer in the western periphery of Nepal. Nepal. J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 3, 118–122.

- Sitoula, R.P.; Singh, S.; Mahaseth, V.; Sharma, A.; Labh, R. Epidemiology and etiological diagnosis of infective keratitis in eastern region of Nepal. Nepal. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 7, 10–15.

- Iyer, S.A.; Tuli, S.S.; Wagoner, R.C. Fungal Keratitis: Emerging Trends and Treatment Outcomes. Eye Contact Lens 2006, 32, 267–271.

- Prajna, N.V.; Krishnan, T.; Mascarenhas, J.; Rajaraman, R.; Prajna, L.; Srinivasan, M.; Raghavan, A.; Oldenburg, C.E.; Ray, K.J.; Zegans, M.E.; et al. The mycotic ulcer treatment trial: A randomized trial comparing natamycin vs voriconazole. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013, 131, 422–429.

- Cheikhrouhou, F.; Makni, F.; Neji, S.; Trigui, A.; Sellami, H.; Trabelsi, H.; Guidara, R.; Fki, J.; Ayadi, A. Epidemiological profile of fungal keratitis in Sfax (Tunisia). J. Mycol. Med. 2014, 24, 308–312.

- Bharathi, M.J.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Meenakshi, R.; Shivakumar, C.; Raj, D.L. Analysis of the risk factors predisposing to fungal, bacterial & Acanthamoeba keratitis in south India. Indian J. Med. Res. 2009, 130, 749–757.

- Sharma, S.; Das, S.; Virdi, A.; Fernandes, M.; Sahu, S.K.; Kumar Koday, N.; Ali, M.H.; Garg, P.; Motukupally, S.R. Re-appraisal of topical 1% voriconazole and 5% natamycin in the treatment of fungal keratitis in a randomised trial. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 99, 1190–1195.

- Das, S.; Sharma, S.; Mahapatra, S.; Sahu, S.K. Fusarium keratitis at a tertiary eye care centre in India. Int. Ophthalmol. 2015, 35, 387–393.

- Basak, S.K.; Basak, S.; Mohanta, A.; Bhowmick, A. Epidemiological and microbiological diagnosis of suppurative keratitis in Gangetic West Bengal, eastern India. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 53, 17–22.

- Cho, N.H.; Shaw, J.E.; Karuranga, S.; Huang, Y.; da Rocha Fernandes, J.D.; Ohlrogge, A.W.; Malanda, B. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2018, 138, 271–281.

- Hine, J.L.; de Lusignan, S.; Burleigh, D.; Pathirannehelage, S.; McGovern, A.; Gatenby, P.; Jones, S.; Jiang, D.; Williams, J.; Elliot, A.J.; et al. Association between glycaemic control and common infections in people with Type 2 diabetes: A cohort study. Diabet. Med. 2017, 34, 551–557.

- Nath, R.; Baruah, S.; Saikia, L.; Devi, B.; Borthakur, A.K.; Mahanta, J. Mycotic corneal ulcers in upper Assam. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 59, 367–371.

- Dan, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhai, H.; Cheng, J.; Wan, L.; Ge, C.; Xie, L. Clinical analysis of fungal keratitis in patients with and without diabetes. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196741.

- Arunga, S.; Kintoki, G.M.; Gichuhi, S.; Onyango, J.; Ayebazibwe, B.; Newton, R.; Leck, A.; Macleod, D.; Hu, V.H.; Burton, M.J. Risk Factors of Microbial Keratitis in Uganda: A Case Control Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2020, 27, 98–104.

- Santos, C.; Parker, J.; Dawson, C.; Ostler, B. Bilateral fungal corneal ulcers in a patient with AIDS-related complex. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1986, 102, 118–119.

- Parrish, C.M.; O’Day, D.M.; Hoyle, T.C. Spontaneous fungal corneal ulcer as an ocular manifestation of AIDS. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1987, 104, 302–303.

- Mselle, J. Fungal keratitis as an indicator of HIV infection in Africa. Trop. Dr. 1999, 29, 133–135.

- Arunga, S.; Kintoki, G.M.; Mwesigye, J.; Ayebazibwe, B.; Onyango, J.; Bazira, J.; Newton, R.; Gichuhi, S.; Leck, A.; Macleod, D.; et al. Epidemiology of Microbial Keratitis in Uganda: A Cohort Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2020, 27, 121–131.

- Anguria, P.; Ntuli, S.; Interewicz, B.; Carmichael, T. Traditional eye medication and pterygium occurrence in Limpopo Province. South Afr. Med. J. 2012, 102, 687–690.

- Bisika, T.; Courtright, P.; Geneau, R.; Kasote, A.; Chimombo, L.; Chirambo, M. Self treatment of eye diseases in Malawi. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement Altern. Med. 2008, 6, 23–29.

- Yorston, D.; Foster, A. Traditional eye medicines and corneal ulceration in Tanzania. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1994, 97, 211–214.

- Lionakis, M.S.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Glucocorticoids and invasive fungal infections. Lancet 2003, 362, 1828–1838.

- Nielsen, S.E.; Nielsen, E.; Julian, H.O.; Lindegaard, J.; Højgaard, K.; Ivarsen, A.; Hjortdal, J.; Heegaard, S. Incidence and clinical characteristics of fungal keratitis in a Danish population from 2000 to 2013. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015, 93, 54–58.

- Cho, C.H.; Lee, S.B. Clinical analysis of microbiologically proven fungal keratitis according to prior topical steroid use: A retrospective study in South Korea. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019, 19, 207.

- Keay, L.J.; Gower, E.W.; Iovieno, A.; Oechsler, R.A.; Alfonso, E.C.; Matoba, A.; Colby, K.; Tuli, S.S.; Hammersmith, K.; Cavanagh, D.; et al. Clinical and Microbiological Characteristics of Fungal Keratitis in the United States, 2001–2007: A Multicenter Study. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 920–926.

- Poole, T.R.G.; Hunter, D.L.; Maliwa, E.M.K.; Ramsay, A.R.C. Aetiology of microbial keratitis in northern Tanzania. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 86, 941–942.

- Gower, E.W.; Keay, L.J.; Oechsler, R.A.; Iovieno, A.; Alfonso, E.C.; Jones, D.B.; Colby, K.; Tuli, S.S.; Patel, S.R.; Lee, S.M.; et al. Trends in fungal keratitis in the United States, 2001 to 2007. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 2263–2267.

- Bullock, J.D.; Warwar, R.E.; Elder, B.L.; Khamis, H.J. Microbiological Investigations of ReNu Plastic Bottles and the 2004 to 2006 ReNu With MoistureLoc-Related Worldwide Fusarium Keratitis Event. Eye Contact Lens 2016, 42, 147–152.

- Buchta, V.; Feuermannová, A.; Váša, M.; Bašková, L.; Kutová, R.; Kubátová, A.; Vejsová, M. Outbreak of fungal endophthalmitis due to Fusarium oxysporum following cataract surgery. Mycopathologia 2014, 177, 115–121.

- Labiris, G.; Troeber, L.; Gatzioufas, Z.; Stavridis, E.; Seitz, B. Bilateral Fusarium oxysporum keratitis after laser in situ keratomileusis. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2012, 38, 2040–2044.

- Jurkunas, U.; Behlau, I.; Colby, K. Fungal keratitis: Changing pathogens and risk factors. Cornea 2009, 28, 638–643.

- Roy, P.; Das, S.; Singh, N.P.; Saha, R.; Kajla, G.; Snehaa, K.; Gupta, V.P. Changing trends in fungal and bacterial profile of infectious keratitis at a tertiary care hospital: A six-year study. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2017, 5, 40–45.

- Ibrahim, M.M.; Vanini, R.; Ibrahim, F.M.; Martins, W.d.P.; Carvalho, R.T.d.C.; Castro, R.S.d.; Rocha, E.M. Epidemiology and medical prediction of microbial keratitis in southeast Brazil. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2011, 74, 7–12.

- Grzybowski, A.; Told, R.; Sacu, S.; Bandello, F.; Moisseiev, E.; Loewenstein, A.; Schmidt-Erfurth, U. 2018 Update on Intravitreal Injections: Euretina Expert Consensus Recommendations. Ophthalmologica 2018, 239, 181–193.

- Luo, D.; Zhu, B.; Zheng, Z.; Zhou, H.; Sun, X.; Xu, X. Subtenon Vs Intravitreal Triamcinolone injection in Diabetic Macular Edema, A prospective study in Chinese population. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 30, 749–754.

- Weinberg, T.; Loewenstein, A. The role of steroids in treating diabetic macular oedema in the era of anti-VEGF. Eye 2020, 34, 1003–1005.

- Durand, M.L. Bacterial and Fungal Endophthalmitis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 597–613.

- Galor, A.; Karp, C.L.; Forster, R.K.; Dubovy, S.R.; Gaunt, M.L.; Miller, D. Subconjunctival mycetoma after sub-Tenon’s corticosteroid injection. Cornea 2009, 28, 933–935.

- Iwahashi, C.; Eguchi, H.; Hotta, F.; Uezumi, M.; Sawa, M.; Kimura, M.; Yaguchi, T.; Kusaka, S. Orbital abscess caused by Exophiala dermatitidis following posterior subtenon injection of triamcinolone acetonide: A case report and a review of literature related to Exophiala eye infections. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 566.