| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cecilia Winata | + 2995 word(s) | 2995 | 2021-04-13 11:45:44 |

Video Upload Options

Enhancers positively influence the activity of its target gene by operating at long-range distances in either direction of the nucleotide sequence. Early heart development is tightly controlled by these cis-regulatory elements and mutations affecting them have been shown to result in devastating forms of congenital heart defect. Therefore, identifying enhancers implicated in heart biology and understanding their mechanism is key to improve diagnosis and therapeutic options.

1. Introduction

The cell specification and tissue remodeling that entails the formation of an organ are complex biological processes which are modulated by coordinated spatiotemporal execution of gene regulatory networks which dictates cell fates and organize specialized cell types into complex three-dimensional units of structure and function [1][2]. These networks are composed of diverse genes and their regulatory elements that evolve at different rates and can undergo various modifications. Non-coding DNA regulatory elements mediate the molecular networks of regulatory processes at the transcriptional, post-transcriptional and post-translational levels [3]. They include promoters [4], silencer [5], insulator [6], and cis- and trans-regulatory elements [7][8].

Enhancers are a major type of cis-regulatory element in the genome which increase the likelihood of transcription of one or more distally located genes [9]. The function of an enhancer was demonstrated for the first time in a non-coding region which contains two 72 base pair (bp) repeats of the simian virus 40 (SV40), which is able to drive efficient transcription of SV40 early genes [10][11][12][13]. Subsequently, it was found that enhancers were associated with genes that exhibit tissue-specific expression. The first cell type-specific enhancer was identified in mammalian B lymphocytes within the IgH locus [14][15][16]. Enormous progress has been made since the first discoveries about enhancer properties and their modus operandi. Enhancers serve as binding sites for transcription factors (TFs) which are necessary for the activation of target gene expression. Through chromatin looping, these regulatory factors are brought into direct physical contact with their target promoters [17][18] and thereby potentiate transcriptional initiation and elongation by interacting with the basal transcriptional machinery and the local chromatin remodeling of target genes [19][20]. More recently, it was found that active enhancer state is associated with the generation of bi-directional non-coding transcripts of the enhancer region known as enhancer RNAs (eRNAs) which are functionally required for its activity [20][21][22][23][24].

The heart is an essential organ which serves to circulate blood throughout the whole body. It is the first organ to form in the embryo. Heart development involves an extraordinary and precisely orchestrated series of molecular processes. The combination of complex morphogenetic events necessary for the formation of the heart results from an evolutionarily conserved gene regulatory network [25][26][27][28][29][30]. A core set of conserved cardiac TFs, such as NK2, MEF2, GATA, Hand and Tbx, is involved in the specification of cardiac cell fate, contractility, morphogenesis, segmentation, and growth of cardiac chambers [1][31]. This set, together with others TFs, govern and stabilize the developmental program of the heart [32][33][34]. Expansion and modifications of this ancestral cardiac network could give rise to hearts with higher structure and function complexity [35][36][37]. Homologs of the cardiac TFs were found in early multicellular organisms (~800 million years ago). These organisms possess a primitive coelom surrounded by cells which express NKX2.5/tinman, a TF necessary for the specification of cardiac fate in higher vertebrates [38]. The specialization of mesodermal cells around the coelom in the phylum Bilateria gave rise to the first primitive cardiac myocytes [39]. A further evolved heart structure is found in Protostomia (e.g., Drosophila) and Deuterostoma (e.g., Amphioxus), in the form of a peristaltic tubular heart arising from a monolayer of contracting mesoderm [38][40][41]. In the phylum Chordata and subsequently in the vertebrates, the primitive linear heart develops looping, unidirectional circulation, enclosed vasculature, and the conduction system. Fish and amphibians had further specializations with regional protein localization in cardiomyocytes, while, in reptiles, birds, and mammals, the heart is further sophisticated with the formation of septa and a four-chambered heart which has lost the ability to regenerate cardiomyocytes [38].

Cardiomyocytes (CMs) are the basic units of cardiac tissue which are specified from a pool of mesodermal progenitors located at the anterior portion of the embryonic lateral plate mesoderm [28][42]. Heart development initiates with the specification of cardiac cell fate with the expression of the homeobox TF tinman in invertebrates or Nkx2.5 in vertebrates. This TF is considered the earliest molecular marker of heart progenitors and is known to interact with the zinc finger TF of the GATA family. In flies, Tinman directly activates Mef2 gene, which encodes transcriptional elements that control myocyte differentiation [33]. The MADS-box protein MEF2 is the most ancient myogenic TF that, via specific combinations of cis-regulatory elements, regulates different muscle gene programs [1]. In zebrafish, the tinman-related gene orthologs nkx2.5 and nkx2.7 are responsible for the earliest step of cardiac genes initiation and regulate the expressions of tbx5 and tbx20 through the heart tube stage [43]. Bmp and Nodal signaling induce nkx2.5 expression and cardiogenic differentiation by inducing gata5 [44].

Following the specification of cardiac progenitors, the beating linear heart tube forms by the convergence of cardiac muscle cells along the ventral midline of the embryo. This linear cardiac structure is composed of extracellular matrix and myocardial and endocardial layers. The GATA family TFs play an essential role in forming the linear heart tube in both invertebrate and vertebrate species [45][46][47]. In vertebrate such as mice and zebrafish, the heart tube subsequently undergoes rightward looping which is essential for the alignment of the heart chambers. The rightward direction of cardiac looping is driven by asymmetric axial signals which include members of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) family, Sonic hedgehog, and Nodal, which are expressed in the lateral mesoderm [44][48]. In mice, frogs, and in zebrafish, the TF Pitx2 is involved in the mediation of left-right signals, which is expressed along the developing organs [48][49]. In addition, in zebrafish, the asymmetric heart looping is controlled by both Nodal-dependent and -independent mechanisms [50].

Despite the wealth of knowledge on TFs regulating heart development, very few enhancers to which they bind and exert their functions have been identified. As TFs bind to enhancers to exert their function, mutations in these regulatory elements can equally affect developmental outcome as mutations in coding regions. Studies in humans have revealed a number of such mutations associated with increased risk to various heart diseases (reviewed in [51][52][53][54]). The discovery of enhancers regulating multiple steps of heart development and regeneration has been greatly facilitated by the development of various approaches which allow their large-scale discovery. These include genome-wide profiling techniques such as chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by DNA sequencing (ChIP-seq) [20][55][56][57][58], computational predictions [59][60], and in vivo assay [61][62][63][64]. These approaches have been used on various model organisms such as the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster [65], mouse Mus musculus [66][67], zebrafish Danio rerio [68][69], and the African clawed frog Xenopus laevis [70][71].

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) was established as a model organism for genetic studies by George Streisinger at the Oregon University in the late 1960s [72]. Several unique biological properties make zebrafish an attractive model for studying heart development. The embryos are transparent, allowing direct in vivo imaging of the developing heart. The zebrafish embryos are not fully dependent upon a functional cardiovascular system, which allows loss of function analysis up to a relatively late developmental stage compared to mammals. Despite having only two chambers, the zebrafish heart develops by means of a mechanism conserved with its mammalian counterpart [73]. The high number of offspring and low cost of maintenance of the zebrafish render it a good model for genomics studies, harboring the potential for rapid discovery of enhancers and other genetic regulatory elements involved in heart development [44][69][74]. The zebrafish entered the genomic field relatively late compared to mammalian and other model organisms as evidenced by the lack of systematic efforts such as ENCODE [75] and modENCODE [65][76] to study its regulatory genetic elements. Nevertheless, such efforts are underway (DANIO-code) and more and more high-throughput techniques are employed to explore its genome [77].

2. The Quest for Enhancers Involved in Heart Development and Function

2.1. Targeted Analysis of Gene Promoter Regions Pinpoints Regulatory Elements Driving Tissue-Specific Expression

Functional characterization of enhancers was traditionally performed by deletion mapping, in which putative regulatory regions upstream of transcription start sites (TSS) of candidate genes are tested by means of a reporter assay to determine its ability to drive specific expression pattern (Table 1). In the zebrafish, these reporter assays can be done in vivo, where a transgenic reporter construct carrying a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter can be directly injected into the embryo and its resulting expression observed live. In one of the earliest applications of the deletion mapping strategy in zebrafish, Meng and colleagues [78] characterized the promoter region of the zebrafish gata1 gene which encodes a TF that plays an important role in hematopoietic development. Using transgene constructs containing deleted and point mutated regions of the gata1 promoter previously identified in zebrafish [79], they identified distinct cis-acting elements that regulate gata1 transcription in various tissues. Systematic deletion on the 5.6 kb genomic fragment upstream of the zebrafish gata1 translation start codon, identified a CACCC box, located between −146 and −142 bp upstream of the translation start codon, which were critical for the initiation of gata1 expression. Furthermore, they showed that the hematopoietic expression of gata1 was maintained by double GATA motif in the distal region between −4635 and −4627 bp. In addition, a 49 bp element located 218 bp upstream of the CACCC element and a CCAAT box at −4643 bp adjacent to the double GATA motif enhanced the erythroid-specific activity of gata1 promoter. Interestingly, a region located between −1776 and −468 was found to repress the gata1 expression in the notochord (a nonhematopoietic tissue), making it one of the earliest discoveries of a repressive hematopoietic regulatory element in the zebrafish. In a similar approach, Muller and colleagues [80] investigated the cis-regulatory elements directing sonic hedgehog (shh) expression in the zebrafish embryo. They focused on the zebrafish shh region, employing an enhancer screening strategy based on co-injection of putative enhancer sequences with a reporter construct [81]. They identified three regulatory elements in introns 1 (ar-A and ar-B) and 2 (ar-C) that mediated floor plate and notochord expression. Deletion fine mapping strategy on ar-C delineated three sub regions of 40 bp essential for its activity. A T-box TF binding site was found in one of these subregions, but none of the three regions contained binding sites of Foxa2, which was previously shown to regulate of shh expression [82], suggesting that other regulatory mechanisms were involved in shh expression. Importantly, these enhancers were able to drive similar expression pattern in zebrafish as well as in mouse embryos, showing that the mechanism controlling shh expression in the midline were evolutionarily conserved. Both these studies therefore showed for the first time that the transient enhancer expression assay using zebrafish embryos could be exploited to identify novel regulatory elements in gene fragments.

Table 1. A list of methods known for enhancer identification.

| Biological Approaches | Work-Principle | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Enhancer-Deletion Approach | Deletion of non-coding cis-regulatory DNA elements can severely disrupt the systemic functions. | [83] |

| Enhancer-Trap Assay | Through microinjection of embryos random integration of a vector-construct with minimal promoter and reporter gene, driving expression if enhancer is present. | [84][85][86][87][88] |

| Transient Transfection Assay | Luciferase reporter plasmid constructs containing promoter and 5′-flanking DNA sequence increases the luciferase expression in the presence of enhancer region. | [81] |

| High-Throughput Techniques | ||

| DNase I-seq | DNase I digestion and DHS fragments mostly comprises cis-regulatory regions (e.g., enhancers). | [89] |

| Epigenomic Profiling (ChIP-Seq) | Enrichment of H3K4me1, H3K4ac, and P300 histone modifications determines the active enhancers. | [20][55][56][60][90][91][92][93] |

| CAGE | High resolution map of TSS and bidirectional transcription patterns defines the precise location of enhancers. | [94][95] |

| NET-CAGE | Capturing 5′-ends of nascent transcripts by fusing two technologies helps to identify unstable transcripts (eRNA). | [8] |

| ATAC-Seq | Accessible chromatin regions encompass enhancer elements. | [58][96] |

The enhancer deletion mapping approach was applied to study the regulatory mechanism of gata4 [83], a TF which plays an essential role in specification of cardiomyocytes and formation of the linear heart tube [45][46][47]. A 14.8 kb fragment upstream of the gata4 transcription initiation site was found to drive GFP expression in both chambers and the valves of the zebrafish heart. Truncation of 7 kb of the distal sequences eliminated expression in the atrium and the atrioventricular valve, while expression was retained in the ventricle and bulboventricular valves. Within this 7 kb distal regulatory region, a 1300 bp region with a cluster of consensus binding sites for T-box TFs was delineated. Mutation of these binding sites significantly reduced reporter gene expression in the heart, providing the first evidence that T-box factors function by directly regulating gata4 expression. This study established that gata4 regulatory elements control gene expression differentially along the rostro-caudal axis and that T-box binding elements in the gata4 promoter contribute to heart-specific expression.

2.2. Large-Scale Enhancer Discovery by Enhancer Trapping Generates Live Markers for Developmental Studies

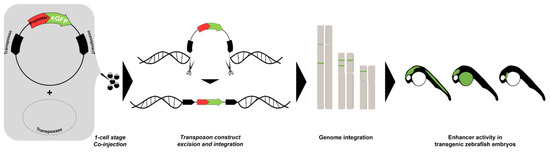

To perform large-scale discovery of enhancers, several methods were developed in model organisms, particularly the zebrafish (Table 1). One of these methods, known as enhancer trapping, offers ease of genetic manipulation by transgenesis (Figure 1). In 2000, Kawakami and colleagues developed a gene trap method in zebrafish using a modified Tol2 transposable element isolated from medaka fish (Oryzias latipes), which encodes a gene for a fully functional transposase capable of catalyzing transposition in the zebrafish germ lineage [84]. The Tol2 element could be inserted in the zebrafish genome and transmitted to the next generation with a low transgenic frequency which prevented to generate hundreds or thousands of transposon insertions. In 2004, they further optimized the Tol2 system, incorporating the Xenopus EF1α enhancer/promoter, the rabbit β-globin intron, the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) reporter gene, and the SV40 polyA signal, which results in EGFP expression that could be observed consistently up to the F4 generation [85]. This established a highly efficient transgenesis method with more than 50% of frequency compared to other methods using naked plasmid DNA or other transposon systems. Applying this technique, Kawakami and colleagues established a collection of transgenic zebrafish lines with a variety of EGFP expression patterns, including ubiquitous, and spatiotemporally restricted patterns. Unique reporter expression patterns were detected in the heart, forebrain, notochord, floor plate, neural crest, and other tissues, establishing a novel transposon-mediated gene trap approach in zebrafish and facilitating studies of vertebrate development and organogenesis. In a parallel effort, Parinov and colleagues also reported the application of an enhancer trap approach in zebrafish using the Tol2 transposon system [86]. They used an enhancer trap construct that carried the EGFP gene as reporter in live zebrafish embryos controlled by a partial promoter of the epithelial keratin4 (krt4) gene. In their initial screen, 37 founders (F0) transmitting the actively expressed EGFP gene to their offspring (F1) were identified. These founders were raised, outcrossed with wild-type, and analyzed up to the F2 generation. In total, they established 28 enhancer trap (ET) lines that exhibited distinct EGFP expression patterns apart from the basal expression from the modified krt4 promoter. The EGFP fluorescence was detected in a variety of tissues and organs, including the central nervous system (CNS), neural crest and its derivatives, notochord, heart, muscles, digestive organs, and kidney. This study, together with that of Kawakami and colleagues, demonstrated that the enhancer trap construct could produce high trapping frequency and specificity.

Figure 1. Enhancer trapping method. The synthetic transposase mRNA, the transposon donor plasmid containing transposable elements with a minimal promoter, and the gene encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) are co-injected into fertilized zebrafish eggs. The construct is excised from the donor plasmid and integrated into the endogenous genome. The activity of the “trapped” enhancer can be visualized in the injected embryo when the inserted transgene is expressed under control of nearby enhancers.

Subsequently, Poon and colleagues [61] further screened the collection of zebrafish enhancer trap lines [86][87][88] and found 18 cardiac enhancer trap (CET) lines with EGFP expression in various part of the embryonic heart. They characterized the EGFP expression pattern in the embryonic heart in vivo using fast scanning confocal microscopy coupled with image reconstruction, producing three-dimensional movies in time. The transgenic lines exhibited EGFP expression in distinct cell layers of the heart, including the endocardium, myocardium, and epicardium. Subsequently, the genomic locations of the transposon insertions were identified by thermal asymmetric interlaced polymerase chain reaction (TAIL-PCR). This screen therefore established a collection of CET lines which could be utilized as a starting point for discovery of cardiac enhancers through further analysis. Furthermore, the cardiac EGFP expression is useful for in vivo studies of heart development.

Balciunas and colleagues [97] modulated the salmonid-originating Sleeping Beauty (SB) transposon-based transgenesis cassette [98] to establish an enhancer trapping in zebrafish. It belongs to the Tc1/mariner superfamily of transposons consisting of two components: the transposase enzyme and a transposon vector containing the terminal-inverted repeat/direct repeat (IR/DR) sequences which moves by a cut-and-paste mechanism. Optimization of this system allowed them to establish nine transgenic lines (ET1–ET9) with different tissue-specific patterns including various tissues of the nervous system, otic vesicle, and the heart in one of the lines (ET7). Detailed analysis on lines ET2 and ET7 revealed that the ET2 line harbors a transposon insertion in the gene encoding poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG) expressed in caudal primary motoneurons. The GFP expression in the ET2 line recapitulated that of the endogenous gene (PARG), indicating that transgene expression was under control of an endogenous enhancer. The ET7 line had closely resembled part of the dual specificity phosphatase 6 (dusp6) expression domain, which is expressed in the midbrain-hindbrain boundary, forebrain, tailbud, branchial arches, developing ear, pectoral fin buds, and other tissues [99], suggesting that the enhancer trap transposon in that line was under control of a subset of dusp6 enhancer elements.

Despite its potential to discover a large number of enhancers, a major drawback of the enhancer trap approach is that the enhancers driving the specific expression are not always easy to identify. Only in some cases, analyses of expression by whole-mount RNA in situ hybridization demonstrated that EGFP expression patterns in enhancer trap lines reflected the tissue-specific expression of nearby genes. Nevertheless, these lines provide a valuable starting point for assays such as chromatin conformation capture, which would allow the identification of the enhancer responsible for driving the reporter expression. In addition, the enhancer trapping screens has generated a wealth of resources in the form of live transgenic markers for various tissues, which is useful for developmental studies.

References

- Olson, E.N. Gene Regulatory Networks in the Evolution and Development of the Heart. Science 2006, 313, 1922–1927.

- Ounzain, S.; Pezzuto, I.; Micheletti, R.; Burdet, F.; Sheta, R.; Nemir, M.; Gonzales, C.; Sarre, A.; Alexanian, M.; Blow, M.J.; et al. Functional Importance of Cardiac Enhancer-Associated Noncoding RNAs in Heart Development and Disease. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014, 76, 55–70.

- Doane, A.S.; Elemento, O. Regulatory Elements in Molecular Networks. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2017, 9, e1374.

- Weingarten-Gabbay, S.; Nir, R.; Lubliner, S.; Sharon, E.; Kalma, Y.; Weinberger, A.; Segal, E. Systematic Interrogation of Human Promoters. Genome Res. 2019, 29, 171–183.

- Jayavelu, N.D.; Jajodia, A.; Mishra, A.; Hawkins, R.D. Candidate Silencer Elements for the Human and Mouse Genomes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–15.

- West, A.G. Insulators: Many Functions, Many Mechanisms. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 271–288.

- Wittkopp, P.J. Genomic Sources of Regulatory Variation in Cis and in Trans. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2005, 62, 1779–1783.

- Hirabayashi, S.; Bhagat, S.; Matsuki, Y.; Takegami, Y.; Uehata, T.; Kanemaru, A.; Itoh, M.; Shirakawa, K.; Takaori-Kondo, A.; Takeuchi, O. NET-CAGE Characterizes the Dynamics and Topology of Human Transcribed Cis-Regulatory Elements. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 1369–1379.

- Gasperini, M.; Tome, J.M.; Shendure, J. Towards a Comprehensive Catalogue of Validated and Target-Linked Human Enhancers. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020, 21, 292–310.

- De Villiers, J.; Olson, L.; Tyndall, C.; Schaffner, W. Transcriptional ‘Enhancers’ from SV40 and Polyoma Virus Show a Cell Type Preference. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982, 10, 7965–7976.

- Spandidos, D.A.; Wilkie, N.M. Host-Specificities of Papillomavirus, Moloney Murine Sarcoma Virus and Simian Virus 40 Enhancer Sequences. EMBO J. 1983, 2, 1193–1199.

- Hansen, U.; Sharp, P.A. Sequences Controlling in Vitro Transcription of SV40 Promoters. EMBO J. 1983, 2, 2293–2303.

- Schirm, S.; Weber, F.; Schaffner, W.; Fleckenstein, B. A Transcription Enhancer in the Herpesvirus Saimiri Genome. EMBO J. 1985, 4, 2669–2674.

- Banerji, J.; Olson, L.; Schaffner, W. A Lymphocyte-Specific Cellular Enhancer Is Located Downstream of the Joining Region in Immunoglobulin Heavy Chain Genes. Cell 1983, 33, 729–740.

- Gillies, S.D.; Morrison, S.L.; Oi, V.T.; Tonegawa, S. A Tissue-Specific Transcription Enhancer Element Is Located in the Major Intron of a Rearranged Immunoglobulin Heavy Chain Gene. Cell 1983, 33, 717–728.

- Mercola, M.; Wang, X.; Olsen, J.; Calame, K. Transcriptional Enhancer Elements in the Mouse Immunoglobulin Heavy Chain Locus. Science 1983, 221, 663–665.

- Zeller, R.W.; Griffith, J.D.; Moore, J.G.; Kirchhamer, C.V.; Britten, R.J.; Davidson, E.H. A Multimerizing Transcription Factor of Sea Urchin Embryos Capable of Looping DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 2989–2993.

- Bulger, M.; Groudine, M. Looping versus Linking: Toward a Model for Long-Distance Gene Activation. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 2465–2477.

- Ong, C.-T.; Corces, V.G. Enhancer Function: New Insights into the Regulation of Tissue-Specific Gene Expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 283–293.

- Wamstad, J.A.; Alexander, J.M.; Truty, R.M.; Shrikumar, A.; Li, F.; Eilertson, K.E.; Ding, H.; Wylie, J.N.; Pico, A.R.; Capra, J.A.; et al. Dynamic and Coordinated Epigenetic Regulation of Developmental Transitions in the Cardiac Lineage. Cell 2012, 151, 206–220.

- De Santa, F.; Barozzi, I.; Mietton, F.; Ghisletti, S.; Polletti, S.; Tusi, B.K.; Muller, H.; Ragoussis, J.; Wei, C.-L.; Natoli, G. A Large Fraction of Extragenic RNA Pol II Transcription Sites Overlap Enhancers. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000384.

- Kowalczyk, M.S.; Hughes, J.R.; Garrick, D.; Lynch, M.D.; Sharpe, J.A.; Sloane-Stanley, J.A.; McGowan, S.J.; Gobbi, M.D.; Hosseini, M.; Vernimmen, D.; et al. Intragenic Enhancers Act as Alternative Promoters. Mol. Cell 2012, 45, 447–458.

- Lai, F.; Orom, U.A.; Cesaroni, M.; Beringer, M.; Taatjes, D.J.; Blobel, G.A.; Shiekhattar, R. Activating RNAs Associate with Mediator to Enhance Chromatin Architecture and Transcription. Nature 2013, 494, 497–501.

- Lam, M.T.Y.; Li, W.; Rosenfeld, M.G.; Glass, C.K. Enhancer RNAs and Regulated Transcriptional Programs. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014, 39, 170–182.

- Nemer, G.; Nemer, M. Regulation of Heart Development and Function through Combinatorial Interactions of Transcription Factors. Ann. Med. 2001, 33, 604–610.

- Chang, C.-P.; Bruneau, B.G. Epigenetics and Cardiovascular Development. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2012, 74, 41–68.

- Li, X.; Martinez-Fernandez, A.; Hartjes, K.A.; Kocher, J.-P.A.; Olson, T.M.; Terzic, A.; Nelson, T.J. Transcriptional Atlas of Cardiogenesis Maps Congenital Heart Disease Interactome. Physiol. Genom. 2014, 46, 482–495.

- Paige, S.L.; Plonowska, K.; Xu, A.; Wu, S.M. Molecular Regulation of Cardiomyocyte Differentiation. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 341–353.

- Lu, F.; Langenbacher, A.; Chen, J.-N. Transcriptional Regulation of Heart Development in Zebrafish. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2016, 3, 14.

- Pawlak, M.; Niescierowicz, K.; Winata, C.L. Decoding the Heart through Next Generation Sequencing Approaches. Genes 2018, 9, 289.

- Bruneau, B.G. Transcriptional Regulation of Vertebrate Cardiac Morphogenesis. Circ. Res. 2002, 90, 509–519.

- Schwartz, R.J.; Olson, E.N. Building the Heart Piece by Piece: Modularity of Cis-Elements Regulating Nkx2-5 Transcription. Development 1999, 126, 4187–4192.

- Srivastava, D.; Olson, E.N. A Genetic Blueprint for Cardiac Development. Nature 2000, 407, 221–226.

- Buckingham, M.; Meilhac, S.; Zaffran, S. Building the Mammalian Heart from Two Sources of Myocardial Cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005, 6, 826–835.

- Fishman, M.C.; Olson, E.N. Parsing the Heart: Genetic Modules for Organ Assembly. Cell 1997, 91, 153–156.

- OOta, S.; Saitou, N. Phylogenetic Relationship of Muscle Tissues Deduced from Superimposition of Gene Trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 856–867.

- Arendt, D. The Evolution of Cell Types in Animals: Emerging Principles from Molecular Studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 868–882.

- Bishopric, N.H. Evolution of the Heart from Bacteria to Man. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1047, 13–29.

- Kawakoshi, A.; Hyodo, S.; Yasuda, A.; Takei, Y. A Single and Novel Natriuretic Peptide Is Expressed in the Heart and Brain of the Most Primitive Vertebrate, the Hagfish (Eptatretus Burgeri). J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003, 31, 209–220.

- Becker, D.L.; Cook, J.E.; Davies, C.S.; Evans, W.H.; Gourdie, R.G. Expression of Major Gap Junction Connexin Types in the Working Myocardium of Eight Chordates. Cell Biol. Int. 1998, 22, 527–543.

- Holland, N.D.; Venkatesh, T.V.; Holland, L.Z.; Jacobs, D.K.; Bodmer, R. Amphink2-Tin, an Amphioxus Homeobox Gene Expressed in Myocardial Progenitors: Insights into Evolution of the Vertebrate Heart. Dev. Biol. 2003, 255, 128–137.

- Brade, T.; Pane, L.S.; Moretti, A.; Chien, K.R.; Laugwitz, K.-L. Embryonic Heart Progenitors and Cardiogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2013, 3, a013847.

- Tu, C.-T.; Yang, T.-C.; Tsai, H.-J. Nkx2.7 and Nkx2.5 Function Redundantly and Are Required for Cardiac Morphogenesis of Zebrafish Embryos. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4249.

- Bakkers, J. Zebrafish as a Model to Study Cardiac Development and Human Cardiac Disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011, 91, 279–288.

- Kuo, C.T.; Morrisey, E.E.; Anandappa, R.; Sigrist, K.; Lu, M.M.; Parmacek, M.S.; Soudais, C.; Leiden, J.M. GATA4 Transcription Factor Is Required for Ventral Morphogenesis and Heart Tube Formation. Genes Dev. 1997, 11, 1048–1060.

- Molkentin, J.D.; Lin, Q.; Duncan, S.A.; Olson, E.N. Requirement of the Transcription Factor GATA4 for Heart Tube Formation and Ventral Morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997, 11, 1061–1072.

- Patient, R.K.; McGhee, J.D. The GATA Family (Vertebrates and Invertebrates). Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2002, 12, 416–422.

- King, T.; Brown, N.A. Embryonic Asymmetry: The Left Side Gets All the Best Genes. Curr. Biol. 1999, 9, R18–R22.

- Campione, M.; Steinbeisser, H.; Schweickert, A.; Deissler, K.; van Bebber, F.; Lowe, L.A.; Nowotschin, S.; Viebahn, C.; Haffter, P.; Kuehn, M.R. The Homeobox Gene Pitx2: Mediator of Asymmetric Left-Right Signaling in Vertebrate Heart and Gut Looping. Development 1999, 126, 1225–1234.

- Noël, E.S.; Verhoeven, M.; Lagendijk, A.K.; Tessadori, F.; Smith, K.; Choorapoikayil, S.; Den Hertog, J.; Bakkers, J. A Nodal-Independent and Tissue-Intrinsic Mechanism Controls Heart-Looping Chirality. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2754.

- Sakabe, N.; Savic, D.; Nobrega, M.A. Transcriptional Enhancers in Development and Disease. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, 238.

- Postma, A.V.; Bezzina, C.R.; Christoffels, V.M. Genetics of Congenital Heart Disease: The Contribution of the Noncoding Regulatory Genome. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 61, 13–19.

- Zaidi, S.; Brueckner, M. Genetics and Genomics of Congenital Heart Disease. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 923–940.

- Chahal, G.; Tyagi, S.; Ramialison, M. Navigating the Non-Coding Genome in Heart Development and Congenital Heart Disease. Differentiation 2019, 107, 11–23.

- Blow, M.J.; McCulley, D.J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, T.; Akiyama, J.A.; Holt, A.; Plajzer-Frick, I.; Shoukry, M.; Wright, C.; Chen, F.; et al. ChIP-Seq Identification of Weakly Conserved Heart Enhancers. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 806–810.

- May, D.; Blow, M.J.; Kaplan, T.; McCulley, D.J.; Jensen, B.C.; Akiyama, J.A.; Holt, A.; Plajzer-Frick, I.; Shoukry, M.; Wright, C.; et al. Large-Scale Discovery of Enhancers from Human Heart Tissue. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 89–93.

- Paige, S.L.; Thomas, S.; Stoick-Cooper, C.L.; Wang, H.; Maves, L.; Sandstrom, R.; Pabon, L.; Reinecke, H.; Pratt, G.; Keller, G.; et al. A Temporal Chromatin Signature in Human Embryonic Stem Cells Identifies Regulators of Cardiac Development. Cell 2012, 151, 221–232.

- Pawlak, M.; Kedzierska, K.Z.; Migdal, M.; Nahia, K.A.; Ramilowski, J.A.; Bugajski, L.; Hashimoto, K.; Marconi, A.; Piwocka, K.; Carninci, P.; et al. Dynamics of Cardiomyocyte Transcriptome and Chromatin Landscape Demarcates Key Events of Heart Development. Genome Res. 2019, 29, 506–519.

- Narlikar, L.; Sakabe, N.J.; Blanski, A.A.; Arimura, F.E.; Westlund, J.M.; Nobrega, M.A.; Ovcharenko, I. Genome-Wide Discovery of Human Heart Enhancers. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 381–392.

- Dickel, D.E.; Barozzi, I.; Zhu, Y.; Fukuda-Yuzawa, Y.; Osterwalder, M.; Mannion, B.J.; May, D.; Spurrell, C.H.; Plajzer-Frick, I.; Pickle, C.S.; et al. Genome-Wide Compendium and Functional Assessment of in Vivo Heart Enhancers. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12923.

- Poon, K.-L.; Liebling, M.; Kondrychyn, I.; Garcia-Lecea, M.; Korzh, V. Zebrafish Cardiac Enhancer Trap Lines: New Tools for in Vivo Studies of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. Dev. Dyn. 2010, 239, 914–926.

- Wang, F.; Yang, Q.; Wu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; Wang, X.; Gui, Y.; Li, Q. Identification of a 42-bp Heart-specific Enhancer of the Notch1b Gene in Zebrafish Embryos. Dev. Dyn. 2019, 248, 426–436.

- Van den Boogaard, M.; van Weerd, J.H.; Bawazeer, A.C.; Hooijkaas, I.B.; van de Werken, H.J.G.; Tessadori, F.; de Laat, W.; Barnett, P.; Bakkers, J.; Christoffels, V.M. Identification and Characterization of a Transcribed Distal Enhancer Involved in Cardiac Kcnh2 Regulation. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 2704–2714.e5.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Wu, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Gui, Y.; Li, Q. Tnni1b-ECR183-D2, an 87 Bp Cardiac Enhancer of Zebrafish. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10289.

- The modENCODE Consortium; Roy, S.; Ernst, J.; Kharchenko, P.V.; Kheradpour, P.; Negre, N.; Eaton, M.L.; Landolin, J.M.; Bristow, C.A.; Ma, L.; et al. Identification of Functional Elements and Regulatory Circuits by Drosophila ModENCODE. Science 2010, 330, 1787–1797.

- Phifer-Rixey, M.; Nachman, M.W. Insights into Mammalian Biology from the Wild House Mouse Mus Musculus. eLife 2015, 4, e05959.

- Han, S.; Yang, A.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.-W.; Park, C.B.; Park, H.-S. Expanding the Genetic Code of Mus Musculus. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14568.

- Woods, I.G.; Kelly, P.D.; Chu, F.; Ngo-Hazelett, P.; Yan, Y.-L.; Huang, H.; Postlethwait, J.H.; Talbot, W.S. A Comparative Map of the Zebrafish Genome. Genome Res. 2000, 10, 1903–1914.

- Howe, K.; Clark, M.D.; Torroja, C.F.; Torrance, J.; Berthelot, C.; Muffato, M.; Collins, J.E.; Humphray, S.; McLaren, K.; Matthews, L.; et al. The Zebrafish Reference Genome Sequence and Its Relationship to the Human Genome. Nature 2013, 496, 498–503.

- Lee-Liu, D.; Méndez-Olivos, E.E.; Muñoz, R.; Larraín, J. The African Clawed Frog Xenopus Laevis: A Model Organism to Study Regeneration of the Central Nervous System. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 652, 82–93.

- Borodinsky, L.N. Xenopus Laevis as a Model Organism for the Study of Spinal Cord Formation, Development, Function and Regeneration. Front. Neural Circuits 2017, 11, 90.

- Streisinger, G.; Walker, C.; Dower, N.; Knauber, D.; Singer, F. Production of Clones of Homozygous Diploid Zebra Fish (Brachydanio Rerio). Nature 1981, 291, 293–296.

- Staudt, D.; Stainier, D. Uncovering the Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Heart Development Using the Zebrafish. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2012, 46, 397–418.

- Yang, H.; Luan, Y.; Liu, T.; Lee, H.J.; Fang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Jin, Q.; Ang, K.C.; et al. A Map of Cis-Regulatory Elements and 3D Genome Structures in Zebrafish. Nature 2020, 588, 337–343.

- The ENCODE Project Consortium. The ENCODE (ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements) Project. Science 2004, 306, 636–640.

- Gerstein, M.B.; Lu, Z.J.; Van Nostrand, E.L.; Cheng, C.; Arshinoff, B.I.; Liu, T.; Yip, K.Y.; Robilotto, R.; Rechtsteiner, A.; Ikegami, K.; et al. Integrative Analysis of the Caenorhabditis Elegans Genome by the ModENCODE Project. Science 2010, 330, 1775–1787.

- Tan, H.; Onichtchouk, D.; Winata, C. DANIO-CODE: Toward an Encyclopedia of DNA Elements in Zebrafish. Zebrafish 2016, 13, 54–60.

- Meng, A.; Tang, H.; Yuan, B.; Ong, B.A.; Long, Q.; Lin, S. Positive and Negative Cis-Acting Elements Are Required for Hematopoietic Expression of Zebrafish GATA-1. Blood 1999, 93, 500–508.

- Long, Q.; Meng, A.; Wang, H.; Jessen, J.R.; Farrell, M.J.; Lin, S. GATA-1 Expression Pattern Can Be Recapitulated in Living Transgenic Zebrafish Using GFP Reporter Gene. Development 1997, 124, 4105–4111.

- Muller, F.; Chang, B.; Albert, S.; Fischer, N.; Tora, L.; Strahle, U. Intronic Enhancers Control Expression of Zebrafish Sonic Hedgehog in Floor Plate and Notochord. Development 1999, 126, 2103–2116.

- Müller, F.; Williams, D.W.; Kobolák, J.; Gauvry, L.; Goldspink, G.; Orbán, L.; Maclean, N. Activator Effect of Coinjected Enhancers on the Muscle-Specific Expression of Promoters in Zebrafish Embryos. Mol. Reprod. Dev. Inc. Gamete Res. 1997, 47, 404–412.

- Chang, B.-E.; Blader, P.; Fischer, N.; Ingham, P.W.; Strähle, U. Axial (HNF3β) and Retinoic Acid Receptors Are Regulators of the Zebrafish Sonic Hedgehog Promoter. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 3955–3964.

- Heicklen-Klein, A.; Evans, T. T-Box Binding Sites Are Required for Activity of a Cardiac GATA-4 Enhancer. Dev. Biol. 2004, 267, 490–504.

- Kawakami, K.; Shima, A.; Kawakami, N. Identification of a Functional Transposase of the Tol2 Element, an Ac-like Element from the Japanese Medaka Fish, and Its Transposition in the Zebrafish Germ Lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 11403–11408.

- Kawakami, K.; Takeda, H.; Kawakami, N.; Kobayashi, M.; Matsuda, N.; Mishina, M. A Transposon-Mediated Gene Trap Approach Identifies Developmentally Regulated Genes in Zebrafish. Dev. Cell 2004, 7, 133–144.

- Parinov, S.; Kondrichin, I.; Korzh, V.; Emelyanov, A. Tol2 Transposon-Mediated Enhancer Trap to Identify Developmentally Regulated Zebrafish Genes in Vivo. Dev. Dyn. 2004, 231, 449–459.

- Choo, B.; Kondrichin, I.; Parinov, S.; Emelyanov, A.; Go, W.; Toh, W.; Korzh, V. Zebrafish Transgenic Enhancer TRAP Line Database (ZETRAP). BMC Dev. Biol. 2006, 6, 1–7.

- Kondrychyn, I.; Garcia-Lecea, M.; Emelyanov, A.; Parinov, S.; Korzh, V. Genome-Wide Analysis of Tol2 Transposon Reintegration in Zebrafish. BMC Genom. 2009, 10, 418.

- Boyle, A.P.; Davis, S.; Shulha, H.P.; Meltzer, P.; Margulies, E.H.; Weng, Z.; Furey, T.S.; Crawford, G.E. High-Resolution Mapping and Characterization of Open Chromatin across the Genome. Cell 2008, 132, 311–322.

- Creyghton, M.P.; Cheng, A.W.; Welstead, G.G.; Kooistra, T.; Carey, B.W.; Steine, E.J.; Hanna, J.; Lodato, M.A.; Frampton, G.M.; Sharp, P.A.; et al. Histone H3K27ac Separates Active from Poised Enhancers and Predicts Developmental State. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 21931–21936.

- Heintzman, N.D.; Stuart, R.K.; Hon, G.; Fu, Y.; Ching, C.W.; Hawkins, R.D.; Barrera, L.O.; Van Calcar, S.; Qu, C.; Ching, K.A.; et al. Distinct and Predictive Chromatin Signatures of Transcriptional Promoters and Enhancers in the Human Genome. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 311–318.

- Heintzman, N.D.; Hon, G.C.; Hawkins, R.D.; Kheradpour, P.; Stark, A.; Harp, L.F.; Ye, Z.; Lee, L.K.; Stuart, R.K.; Ching, C.W.; et al. Histone Modifications at Human Enhancers Reflect Global Cell-Type-Specific Gene Expression. Nature 2009, 459, 108–112.

- Rada-Iglesias, A.; Bajpai, R.; Swigut, T.; Brugmann, S.A.; Flynn, R.A.; Wysocka, J. A Unique Chromatin Signature Uncovers Early Developmental Enhancers in Humans. Nature 2011, 470, 279–283.

- Andersson, R.; Gebhard, C.; Miguel-Escalada, I.; Hoof, I.; Bornholdt, J.; Boyd, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Schmidl, C.; Suzuki, T. An Atlas of Active Enhancers across Human Cell Types and Tissues. Nature 2014, 507, 455–461.

- Sakaguchi, Y.; Nishikawa, K.; Seno, S.; Matsuda, H.; Takayanagi, H.; Ishii, M. Roles of Enhancer RNAs in RANKL-Induced Osteoclast Differentiation Identified by Genome-Wide Cap-Analysis of Gene Expression Using CRISPR. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–5.

- Galang, G.; Mandla, R.; Ruan, H.; Jung, C.; Sinha, T.; Stone, N.R.; Wu, R.S.; Mannion, B.J.; Allu, P.K.R.; Chang, K.; et al. ATAC-Seq Reveals an Isl1 Enhancer That Regulates Sinoatrial Node Development and Function. Circ. Res 2020, 127, 1502–1518.

- Balciunas, D.; Davidson, A.E.; Sivasubbu, S.; Hermanson, S.B.; Welle, Z.; Ekker, S.C. Enhancer Trapping in Zebrafish Using the Sleeping Beauty Transposon. BMC Genom. 2004, 5, 62.

- Ivics, Z.; Hackett, P.B.; Plasterk, R.H.; Izsvák, Z. Molecular Reconstruction of Sleeping Beauty, a Tc1-like Transposon from Fish, and Its Transposition in Human Cells. Cell 1997, 91, 501–510.

- Kawakami, Y.; Rodríguez-León, J.; Koth, C.M.; Büscher, D.; Itoh, T.; Raya, Á.; Ng, J.K.; Esteban, C.R.; Takahashi, S.; Henrique, D.; et al. MKP3 Mediates the Cellular Response to FGF8 Signalling in the Vertebrate Limb. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003, 5, 513–519.