| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Milica Bozic | + 1724 word(s) | 1724 | 2021-04-16 07:57:21 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 1724 | 2021-04-19 11:59:19 | | |

Video Upload Options

Renal fibrosis is a complex disorder characterized by the destruction of kidney parenchyma. There is currently no cure for this devastating condition. It has been demonstrated that extracellular vesicle (EV)-mediated crosstalk between various kidney cells has an essential role in the development of renal fibrosis. Importantly, EVs released from various mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and other cell sources have emerged as a powerful cell-free therapy in different models of renal fibrosis due to their antifibrotic characteristics and tissue regeneration capacity.

1. Introduction

Renal fibrosis is the final manifestation of chronic kidney disease (CKD), characterized by progressive destruction of kidney parenchyma and the subsequent loss of renal function. Due to the complexity of this condition and the inability to establish a proper hierarchy of involved mechanisms during the development of renal fibrosis, there is currently no effective antifibrotic therapy in clinical use [1]. Over the past decade, extensive research has focused on the prevention and reversal of kidney fibrosis, with specific emphasis on the regeneration of the injured parenchyma using, among others, different cell-based approaches with multipotent progenitor cells for the reparation of an injured organ [1]. Nevertheless, among diverse approaches proposed as potential therapies for renal fibrosis, the use of extracellular vesicles (EVs) as a cell-free therapeutic approach has now started to be extensively investigated.

In recent years, numerous studies have pointed to EVs as important players in various physiological and pathophysiological processes, including kidney diseases. Apart from being active players in various biological processes [2][3], EVs have been identified as important means of communication alongside the nephron [4]. Furthermore, owing to their versatile characteristics, EVs represent a potential basis for the development of novel therapies [5][6]. Thus, EVs derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have emerged as a powerful cell-free therapy for a variety of disease states, renal fibrosis being one of them [7].

2. Extracellular Vesicles: Classification, Biogenesis, and Function

EVs are membrane-limited vesicles that cells release in order to transfer biomolecules to other cells and thus communicate with them [2]. In the last decade, knowledge about EVs vastly expanded, revealing EVs as a novel paradigm in intercellular communication. Numerous studies have demonstrated the involvement of EVs in various physiological and pathophysiological processes, hence highlighting their importance for both functioning of the organism and the design of novel diagnostic tools and therapies [2][3].

EVs encompass diverse populations of membrane-limited vesicles released by virtually all cells in the organism. The diversity of EVs refers to their biogenesis, composition, size, and role [8].

2.1. Classification and Biogenesis of Extracellular Vesicles

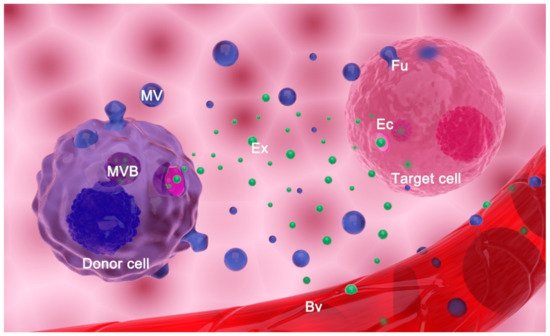

EVs are currently classified into two main types based on their biogenesis: exosomes and microvesicles (MVs) (Figure 1). In a wider sense, apoptotic bodies may also be classified as EVs, although their involvement in intercellular communication is far less studied and will not be considered here [2][8]. The process of biogenesis encompasses the selection of cargo molecules, inducing curvature of the membrane and detachment of the vesicle. Although details of these processes are still elusive, significant advances in understanding their basics have recently been made. Hence, the formation of an exosome starts in a multivesicular body (MVB). Two main mechanisms govern this process: endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)-dependent mechanism or ESCRT-independent mechanism [8][9]. In the former, ubiquitinated proteins are selected by the members of the ESCRT complex [9][10][11], while in the latter, sphingosine-1-phosphate, Hsc70, and tetraspanins participate in protein selection [9][12]. In addition, the sorting of some proteins may depend on their interaction with lipid raft components [13]. The sorting of miRNAs is based on their interaction with RNA-binding proteins that are targeted to EVs, their abundance in cells, and their sequence [8][14]. Invagination of the MVB limiting membrane is accomplished by the action of phosphatidic acid and sphingolipids [15][16]. This process results in the formation of vesicles in the lumen of MVB—intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) (Figure 1). In order for cells to release ILVs as exosomes, MVB must be targeted to and fused with the plasma membrane. The process of guidance of MVBs to the plasma membrane is governed by RAB proteins [8][17][18], while the fusion of MVB with the plasma membrane is mediated by RAB and SNARE proteins (N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion attachment protein (SNAP) receptors) [19].

Figure 1. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) release and transfer. EVs comprise exosomes (Exs), microvesicles (MVs), and apoptotic bodies (not shown). Exs are released from a donor cell upon fusion of a multivesicular body (MVB) with the plasma membrane. Microvesicles (MVs) are formed by budding of the originating cell’s plasma membrane. EVs reach target cells of the same tissue or they are transferred by body fluids to distant cells (i.e., EVs enter blood vessels (Bv) and are transferred by blood to distant organs/tissues/cells). EVs may deliver information to the target cell by (a) fusion (Fu) with its plasma membrane; (b) endocytosis (Ec) of EVs by target cells; or (c) interaction of surface molecules on EVs and the cell (not shown).

In contrast to exosomes, microvesicles are formed by direct outward budding of the plasma membrane. Reshaping of the membrane is accomplished by changing its lipid composition at the budding site and disassembly of the cytoskeleton by Ca++ ions-dependent enzymes, although it has been shown that specific members of the ESCRT complex are also involved in this process [8][20][21].

Even though modes of biogenesis define two main types of EVs, their other properties are not so distinctive. As for composition, EVs can carry all types of biomolecules (proteins, RNA, lipids, metabolites) involved in a number of processes such as adhesion, metabolism, signal transduction, membrane fusion, organization and trafficking, etc., in addition to molecules involved in EVs biogenesis [2][8]. The composition of a particular EV population also depends on the type and physiological condition of its cell of origin [22]. Different molecules specific for cell type or physiological states, such as specific surface receptors, enzymes, or cell markers, may be packed into EVs making them useful as liquid biopsies [23].

All these biogenesis and sorting mechanisms give rise to subpopulations of EVs with partially overlapping cargo [24]. Due to this overlapping and despite the presence of some biogenesis machinery components, no true marker of EV types exists. Although tetraspanins (CD63, CD9, and CD81) are being used as exosome markers, they are present on both exosomes and microvesicles and thus are unable to distinguish these two types of EVs [25].

EVs also differ in size and shape. Although it is often stated that exosomes are generally smaller than microvesicles (30–150 nm vs. 100–1000 nm), their sizes in fact overlap and thus cannot be used as a distinctive criterion for the determination of the EV type [26]. As for morphology, most of the EVs of both types have a round shape under an electron microscope, but other forms (elongated and multilayered vesicles) are also observed, adding to EVs heterogeneity. It should be noted that most of the available data have been derived from heterogeneous populations of EVs, comprising both exosomes and microvesicles and their subpopulations since there is no method available for their complete and precise separation [23][27][28]. Additionally, the terms “exosomes” and “microvesicles” have been used in the literature in an inconsistent manner. Nevertheless, in this review, we will use original terms for EVs described by authors in their publications.

2.2. Main Proposed Functions of Extracellular Vesicles

EVs have numerous roles in the body. They are important players in virtually all physiological processes such as placentation, embryonic development, immunity, coagulation, liver homeostasis, nervous system function, tissue repair, and kidney function [2][29]. EVs also participate as key communicators in pathophysiological processes such as cancer, diabetes, atherosclerosis, and endothelial dysfunction, cardiovascular and immune diseases, inflammation, obesity, fibrosis, etc. [3][30][31]. To exert their roles, EVs may use biofluids to reach the target cell and are able to cross the blood–tissue barrier. EVs deliver bio-information to target cells either by the interaction of surface molecules on EVs and the cell or through uptake/fusion of EVs by a target cell [2][32][33], where proteins and RNA can both be effector molecules.

Aside from their fundamental roles in the organism, EVs can have valuable functions as either diagnostic or therapeutic agents, or the combination of both, known as theranostics tools. EVs reflect the physiological state of the cell they originate from, and they are readily available in biofluids, and as such, they can be used in novel diagnostic platforms [5][34]. This is especially important for the diagnosis of diseases in organs in which tissue biopsy should be avoided whenever possible, such as brain or kidneys. Of note, EVs in urine (uEVs) can originate from different parts of the urinary tract, including the kidney. Carrying diverse molecular cargo from parental cells, uEVs represent an excellent readout of the physiological and pathophysiological state of different parts of the nephron. Thus, uEVs have drawn significant attention as potential biomarkers for diagnostic and prognostic purposes in various renal diseases [35]. For instance, miR-146a from urinary exosomes (uEx) was proposed as a potential biomarker of albuminuria in essential hypertension [36], while miR-29c was suggested as a novel, noninvasive marker for renal fibrosis [37]. miR-145 from uEx was demonstrated to be a promising candidate biomarker for type 1 diabetic nephropathy (DN) [38], while miR-192 was shown to be useful as a predictor of early stage DN [39]. Moreover, CD2AP mRNA in urinary exosomes has been suggested as a noninvasive tool for the detection of changes in kidney function and tubulointerstitial fibrosis, while CCL2 mRNA has been shown as a good predictor of renal function deterioration in IgAN [40]. In addition to miRNAs and mRNAs, various proteins in uEVs were shown to be biomarkers for different renal diseases, among them fetuin-A, ATF3, WT-1, aquaporin-1, etc. [30][41][42][43]. Since the use of EVs as potential diagnostic and prognostic tools for renal diseases has been covered elsewhere [30][41][42][43][44], in this review, we will focus our attention on the potential therapeutic utility of EVs in renal diseases.

Specific properties of EVs such as biocompatibility, biological barrier crossing, selective targeting, and the possibility to be modified make these vesicles a very promising basis for the development of novel therapies [5][6]. Importantly, EVs convey effects of cell therapy without presenting the same hazard as live cells, such as the case for EVs from mesenchymal stem cells (MSC-EVs) [45]. EVs have already been shown to be a beneficial therapy as antitumor vaccines [46], as immune-suppressive agents in graft-vs-host disease [47], and as drug-delivery agents [48][49]. As fundamental tools in cellular communication, EVs hold great promise for both understanding processes that take place in the organism and the design of novel diagnostic and therapeutic tools.

References

- Zeisberg, M.; Kalluri, R. Cellular mechanisms of tissue fibrosis. 1. Common and organ-specific mechanisms associated with tissue fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013, 304, C216–C225.

- Yáñez-Mó, M.; Siljander, P.R.; Andreu, Z.; Zavec, A.B.; Borràs, F.E.; Buzas, E.I.; Buzas, K.; Casal, E.; Cappello, F.; Carvalho, J.; et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 27066.

- Harrison, P.G.C.; Sargent, I.L. Extracellular Vesicles in Health and Disease, 1st ed.; Harrison, P.G.C., Sargent, I.L., Eds.; Jenny Stanford Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2014.

- Borges, F.T.; Reis, L.A.; Schor, N. Extracellular vesicles: Structure, function, and potential clinical uses in renal diseases. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2013, 46, 824–830.

- Fais, S.; O’Driscoll, L.; Borras, F.E.; Buzas, E.; Camussi, G.; Cappello, F.; Carvalho, J.; Cordeiro da Silva, A.; Del Portillo, H.; El Andaloussi, S.; et al. Evidence-Based Clinical Use of Nanoscale Extracellular Vesicles in Nanomedicine. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 3886–3899.

- Klyachko, N.L.; Arzt, C.J.; Li, S.M.; Gololobova, O.A.; Batrakova, E.V. Extracellular Vesicle-Based Therapeutics: Preclinical and Clinical Investigations. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1171.

- Rockel, J.S.; Rabani, R.; Viswanathan, S. Anti-fibrotic mechanisms of exogenously-expanded mesenchymal stromal cells for fibrotic diseases. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 101, 87–103.

- Greening, D.W.; Simpson, R.J. Understanding extracellular vesicle diversity-current status. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2018, 15, 887–910.

- Teng, F.; Fussenegger, M. Shedding Light on Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis and Bioengineering. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 2020, 8, 2003505.

- Li, X.; Liu, R.; Huang, Z.; Gurley, E.C.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; He, H.; Yang, H.; Lai, G.; Zhang, L.; et al. Cholangiocyte-derived exosomal long noncoding RNA H19 promotes cholestatic liver injury in mouse and humans. Hepatology 2018, 68, 599–615.

- Romano, E.; Netti, P.A.; Torino, E. Exosomes in Gliomas: Biogenesis, Isolation, and Preliminary Applications in Nanomedicine. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 319.

- Reddy, V.S.; Madala, S.K.; Trinath, J.; Reddy, G.B. Extracellular small heat shock proteins: Exosomal biogenesis and function. Cell Stress Chaperones 2018, 23, 441–454.

- Skryabin, G.O.; Komelkov, A.V.; Savelyeva, E.E.; Tchevkina, E.M. Lipid Rafts in Exosome Biogenesis. Biochemistry 2020, 85, 177–191.

- Abels, E.R.; Breakefield, X.O. Introduction to Extracellular Vesicles: Biogenesis, RNA Cargo Selection, Content, Release, and Uptake. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 36, 301–312.

- Verderio, C.; Gabrielli, M.; Giussani, P. Role of sphingolipids in the biogenesis and biological activity of extracellular vesicles. J. Lipid Res. 2018, 59, 1325–1340.

- Ghossoub, R.; Lembo, F.; Rubio, A.; Gaillard, C.B.; Bouchet, J.; Vitale, N.; Slavík, J.; Machala, M.; Zimmermann, P. Syntenin-ALIX exosome biogenesis and budding into multivesicular bodies are controlled by ARF6 and PLD2. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3477.

- Ostrowski, M.; Carmo, N.B.; Krumeich, S.; Fanget, I.; Raposo, G.; Savina, A.; Moita, C.F.; Schauer, K.; Hume, A.N.; Freitas, R.P.; et al. Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome secretion pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 19–30, sup pp. 11–13.

- Blanc, L.; Vidal, M. New insights into the function of Rab GTPases in the context of exosomal secretion. Small GTPases 2018, 9, 95–106.

- Hyenne, V.; Labouesse, M.; Goetz, J.G. The Small GTPase Ral orchestrates MVB biogenesis and exosome secretion. Small GTPases 2018, 9, 445–451.

- Hugel, B.; Martínez, M.C.; Kunzelmann, C.; Freyssinet, J.M. Membrane microparticles: Two sides of the coin. Physiology 2005, 20, 22–27.

- Sedgwick, A.E.; D’Souza-Schorey, C. The biology of extracellular microvesicles. Traffic 2018, 19, 319–327.

- Kolonics, F.; Szeifert, V.; Timár, C.I.; Ligeti, E.; Lőrincz, Á. The Functional Heterogeneity of Neutrophil-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Reflects the Status of the Parent Cell. Cells 2020, 9, 2718.

- Vagner, T.; Chin, A.; Mariscal, J.; Bannykh, S.; Engman, D.M.; Di Vizio, D. Protein Composition Reflects Extracellular Vesicle Heterogeneity. Proteomics 2019, 19, e1800167.

- Kowal, J.; Arras, G.; Colombo, M.; Jouve, M.; Morath, J.P.; Primdal-Bengtson, B.; Dingli, F.; Loew, D.; Tkach, M.; Théry, C. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E968–E977.

- Jeppesen, D.K.; Fenix, A.M.; Franklin, J.L.; Higginbotham, J.N.; Zhang, Q.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Liebler, D.C.; Ping, J.; Liu, Q.; Evans, R.; et al. Reassessment of Exosome Composition. Cell 2019, 177, 428–445.e418.

- Raposo, G.; Stoorvogel, W. Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 200, 373–383.

- Willms, E.; Cabañas, C.; Mäger, I.; Wood, M.J.A.; Vader, P. Extracellular Vesicle Heterogeneity: Subpopulations, Isolation Techniques, and Diverse Functions in Cancer Progression. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 738.

- Huang, G.; Lin, G.; Zhu, Y.; Duan, W.; Jin, D. Emerging technologies for profiling extracellular vesicle heterogeneity. Lab Chip 2020, 20, 2423–2437.

- Karpman, D.; Ståhl, A.L.; Arvidsson, I. Extracellular vesicles in renal disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 545–562.

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, H.; Yao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Z. Extracellular vesicles in diagnosis and therapy of kidney diseases. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2016, 311, F844–F851.

- Malloci, M.; Perdomo, L.; Veerasamy, M.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Simard, G.; Martínez, M.C. Extracellular Vesicles: Mechanisms in Human Health and Disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2019, 30, 813–856.

- Maas, S.L.N.; Breakefield, X.O.; Weaver, A.M. Extracellular Vesicles: Unique Intercellular Delivery Vehicles. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 172–188.

- Mulcahy, L.A.; Pink, R.C.; Carter, D.R. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3.

- Ailuno, G.; Baldassari, S.; Lai, F.; Florio, T.; Caviglioli, G. Exosomes and Extracellular Vesicles as Emerging Theranostic Platforms in Cancer Research. Cells 2020, 9, 2569.

- Sun, I.O.; Lerman, L.O. Urinary Extracellular Vesicles as Biomarkers of Kidney Disease: From Diagnostics to Therapeutics. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 311.

- Perez-Hernandez, J.; Olivares, D.; Forner, M.J.; Ortega, A.; Solaz, E.; Martinez, F.; Chaves, F.J.; Redon, J.; Cortes, R. Urinary exosome miR-146a is a potential marker of albuminuria in essential hypertension. J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 228.

- Lv, L.L.; Cao, Y.H.; Ni, H.F.; Xu, M.; Liu, D.; Liu, H.; Chen, P.S.; Liu, B.C. MicroRNA-29c in urinary exosome/microvesicle as a biomarker of renal fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2013, 305, F1220–F1227.

- Barutta, F.; Tricarico, M.; Corbelli, A.; Annaratone, L.; Pinach, S.; Grimaldi, S.; Bruno, G.; Cimino, D.; Taverna, D.; Deregibus, M.C.; et al. Urinary exosomal microRNAs in incipient diabetic nephropathy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73798.

- Jia, Y.; Guan, M.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, C.; Xu, W.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, L.; Xue, Y. miRNAs in Urine Extracellular Vesicles as Predictors of Early-Stage Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 7932765.

- Lv, L.L.; Feng, Y.; Tang, T.T.; Liu, B.C. New insight into the role of extracellular vesicles in kidney disease. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 731–739.

- Gámez-Valero, A.; Lozano-Ramos, S.I.; Bancu, I.; Lauzurica-Valdemoros, R.; Borràs, F.E. Urinary extracellular vesicles as source of biomarkers in kidney diseases. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 6.

- De Palma, G.; Sallustio, F.; Schena, F.P. Clinical Application of Human Urinary Extracellular Vesicles in Kidney and Urologic Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1043.

- Erdbrügger, U.; Le, T.H. Extracellular Vesicles in Renal Diseases: More than Novel Biomarkers? J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 12–26.

- Merchant, M.L.; Rood, I.M.; Deegens, J.K.J.; Klein, J.B. Isolation and characterization of urinary extracellular vesicles: Implications for biomarker discovery. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 731–749.

- Zhao, T.; Sun, F.; Liu, J.; Ding, T.; She, J.; Mao, F.; Xu, W.; Qian, H.; Yan, Y. Emerging Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-derived Exosomes in Regenerative Medicine. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 14, 482–494.

- Viaud, S.; Ploix, S.; Lapierre, V.; Théry, C.; Commere, P.H.; Tramalloni, D.; Gorrichon, K.; Virault-Rocroy, P.; Tursz, T.; Lantz, O.; et al. Updated technology to produce highly immunogenic dendritic cell-derived exosomes of clinical grade: A critical role of interferon-γ. J. Immunother. 2011, 34, 65–75.

- Kordelas, L.; Rebmann, V.; Ludwig, A.K.; Radtke, S.; Ruesing, J.; Doeppner, T.R.; Epple, M.; Horn, P.A.; Beelen, D.W.; Giebel, B. MSC-derived exosomes: A novel tool to treat therapy-refractory graft-versus-host disease. Leukemia 2014, 28, 970–973.

- Saari, H.; Lázaro-Ibáñez, E.; Viitala, T.; Vuorimaa-Laukkanen, E.; Siljander, P.; Yliperttula, M. Microvesicle- and exosome-mediated drug delivery enhances the cytotoxicity of Paclitaxel in autologous prostate cancer cells. J. Control. Release 2015, 220, 727–737.

- El Andaloussi, S.; Lakhal, S.; Mäger, I.; Wood, M.J. Exosomes for targeted siRNA delivery across biological barriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 391–397.