| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ruben de Dios | + 1928 word(s) | 1928 | 2021-04-13 11:12:23 | | | |

| 2 | Francisca Reyes-Ramírez | Meta information modification | 1928 | 2021-04-15 19:24:51 | | | | |

| 3 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 1928 | 2021-04-16 06:06:55 | | |

Video Upload Options

The ability of bacterial core RNA polymerase (RNAP) to interact with different σ factors, thereby forming a variety of holoenzymes with different specificities, represents a powerful tool to coordinately reprogram gene expression. Extracytoplasmic function σ factors (ECFs), which are the largest and most diverse family of alternative σ factors, frequently participate in stress responses. The classification of ECFs in 157 different groups according to their phylogenetic relationships and genomic context has revealed their diversity.

1. Introduction and Aim of this Entry

Bacteria, like all other living organisms, have adapted and evolved to inhabit a specific environment, tuning their physiology and metabolism to the pervading conditions provided by their habitat. However, bacteria also need to be prepared to face constant changes in their environment. These fluctuations may lead to important deviations from the optimal growth conditions for a species, threatening bacterial survival, and are known as stress conditions. Stress may be generated by environmental changes and by the biochemical processes performed in the cell, although it may also appear as nutrient starvation or interactions with a host. Furthermore, a stress-inducing condition is subjective and specific for each species, so that different bacterial representatives may differ in their response to the same stimulus.

When the conditions shift to a less favorable situation, bacteria fight for survival by activating a number of mechanisms and regulatory circuits whose main effect is the mitigation, or removal, of the stress. The gene products synthesized to overcome stress conditions are variable depending on the stress. For example, temperature shifts may lead to the production of chaperones that aid in protein folding and proteases to remove misfolded proteins [1]. These shifts can also result in the production of proteins involved in maintaining the fluidity and functionality of the cell membrane [2]. Oxidative stress can be overcome by expressing catalases or peroxiredoxins [3][4], which catalyze the conversion of ROS (reactive oxygen species) into harmless compounds before they can damage cell structures. Alternatively, the response can result in the production of components that repair already damaged proteins, such as thioredoxins and glutaredoxins [5][6]. The host immune system, which is activated upon bacterial infection, can also be considered a stress for a pathogen and can result in activation of mechanisms to evade the host defenses [7]. These are the so-called bacterial stress responses, which comprise sensing of the stress and the ultimate activation of the resistance system through a signal transduction process. Actually, any type of bacterial signal transduction mechanism (reviewed in [8]) may be used to exert these responses, as long as its goal is to prepare the cell to face a threatening situation. However, from a classical point of view, bacterial signaling is performed by one- and two-component systems (OCSs and TCSs, respectively), which may introduce the added complexity of a phosphorelay when more than one phosphotransfer step occurs. Recently, Ser/Thr kinase systems started to gain relevance in the bacterial world, since they were originally thought to have a minor role compared to their functions in Eukarya [9]. This occurs despite sharing a common evolutionary origin [10] and contrasting with the His/Asp kinase/phosphotransfer mechanisms on which most TCSs rely.

Besides these mechanisms to regulate the activation of stress responses, alternative σ factors can also be used by bacteria. σ factors are subunits of the RNA polymerase (RNAP) holoenzyme essential for transcription initiation, due to their role in guiding the catalytic core of the RNAP in promoter recognition. Moreover, their specific helicase activity on the -10 box facilitates the formation of the transcription bubble through formation of the open complex. Apart from the vegetative σ70 factor, which ensure the bulk of the transcriptional control of house-keeping genes, alternative σ factors control the expression of a number of specific genes (regulons) with a defined collective function, which may go beyond the stress response. In the early 1990s, certain representatives of this group caught the attention of molecular microbiologists (reviewed in [11]) because of their small size. They comprise the essential domains allowing RNAP interaction, promoter-binding and initiation activity. They were named extracytoplasmic function σ factors (ECFs), since at that time they were thought to respond exclusively to environmental cues. Indeed, most of them are activated by external stimuli, although they can also respond to cytoplasmic signals. Due to their diversity and the relative simplicity of their mechanism of action, they have stood out as a versatile and powerful bacterial tool to efficiently activate stress responses [12].

2. Bacterial σ Factor Families

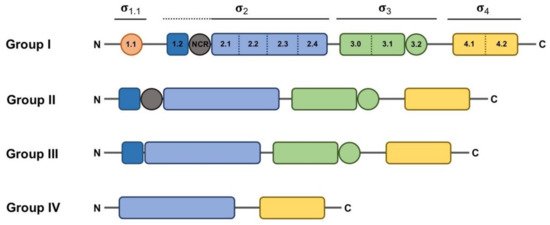

When considered from a structural point of view, σ factors can be divided in two main, structurally unrelated families: one large group includes the primary σ70 family, and the other much smaller group includes the RpoN family (classically known as σ54 or σN), [13][14]. The RpoN family is generally represented by one member per bacterial genome. Although the difference between these two families is not the main focus of this review, it is nevertheless important to stress that RpoN acts in concert with ATP-dependent activators to help unwind the double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) near the transcription start site (TSS) to initiate transcription. In contrast, RNAP holoenzymes formed with σ70 family members melt the DNA near the TSS in an ATP-independent manner and without the aid of additional regulatory proteins [15]. The σ2 domain is able to melt the DNA at the -10 box once the RNAP holoenzyme is correctly positioned thanks to the DNA-binding activity of σ4 and σ3 domains to other promoter regions, such as the -35 box and the extended -10 region, respectively [16]. These structural domains, plus another additional domain with non-essential activity for promoter binding (σ1.1), form the basis of the typical structure feature of the primary σ70 factor, ascribed to Group I (Figure 1). σ factors belonging to Groups II–IV are considered alternative, because they are usually not essential for cell viability and may diverge from Group I in the presence of certain domains. Group II σ factors, with one well-characterized example in Escherichia coli RpoS, conserve the same domain architecture as the primary σ70 factor (RpoD in E. coli) except for the absence of the region σ1.1 [17], and their absence does not result in lethality. Thus, they are generally defined as non-essential σ70 homologs. Members of Group III, such as E. coli RpoH and FliA, essentially conserve domains σ2, σ3 and σ4 [17]. Although σ3 and σ4 bind different promoter regions, they are considered redundant, since the RNAP holoenzyme can bind and orientate efficiently in the absence of one of these domains or one of their DNA-binding determinants [16]. ECFs comprise Group IV with their structure being determined by the presence of only domains σ2 and σ4 separated by a linker shorter than 50 residues. Actually, “Group IV” would be a more appropriate term to describe these σ factors, since it is meanwhile clear that some ECFs respond to intracellular stimuli [13].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the domain and subdomain architecture present in the different groups of the σ70 family. Regions that do not have a direct interaction with DNA appear as circles. Domains σ1.1, core σ2, σ3 and σ4 appear in orange, blue, green and yellow, respectively. Subdomains σ1.2 and σNCR (non-conserved region), which are considered part of the σ2 domain but are not conserved in all σ70 family groups, are depicted in dark blue and gray, respectively, and indicated with a dotted line. The extent of the rest of the σ domains is indicated with solid lines.

Classification of σ70 family members has relied on the presence of various well-conserved protein domains and subdomains (Figure 1). However, in some cases, the boundaries of this classification are diffuse, as some proteins may act as σ factors despite showing low similarity or a different organization, or vice versa, some proteins may have a structure resembling a σ factor whilst not functioning as such. For instance, a group of proteins encoded by Clostridium species that control the production of extracellular toxins, such as TcdR or BotR, function as σ factors at the biochemical level, and even show somewhat recognizable σ2 and σ4 domains [18][19]. However, the marked sequence divergence from Group IV representatives prevents a clear-cut classification into that group. This led to the proposition of these proteins as members of a novel category (Group V), branching from Group IV. Another example of these hard-to-define σ elements is the SigO-RsoA system, formerly YvrI-YvrHa [20][21]. In this pair, the σ4 and σ2 domains are split into separate SigO and RsoA proteins, respectively, and together are able to initiate the transcription of the oxdC-yvrL, yvrJ and yvrI-yvrHa operons. Finally, the response regulator PhyR, whose function will be explained below in more detail, has a N-terminal σ-like domain [22], and although this domain reveals a correct ECF structure, the regions responsible for the interaction with the promoter sequence and the core RNAP appear degenerated, preventing it acting in transcription initiation. Instead, upon activation of the PhyR protein, this domain serves to titrate the anti-σ factor NepR from its cognate ECF EcfG, thus triggering the alphaproteobacterial General Stress Response (GSR).

3. Transcription Initiation: σ70 Factor vs. ECFs

Clearly, the regulation of σ factor availability and/or activity is a powerful means by which gene expression can be regulated, particularly because different RNAP holoenzymes can initiate the transcription of diverse gene clusters at the same time by swapping only one subunit. Thanks to many structural and functional studies deciphering the catalytic mechanism of RNA polymerase, many aspects related to both promoter recognition and dsDNA strand separation are known for the primary σ70 factor [23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34]. More recently, a number of studies have shed light on the structures and mechanistic differences of transcriptional initiation driven by ECFs in comparison with the σ70 factor [35][36][37].

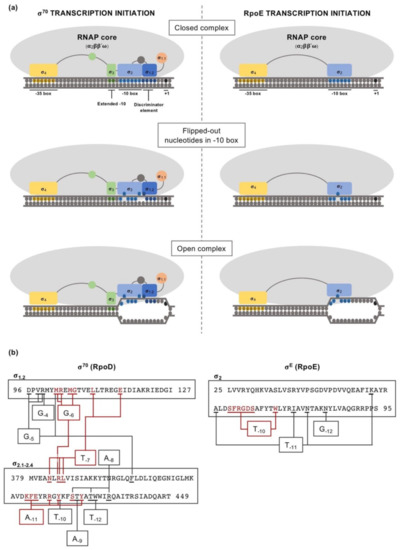

Taken as a paradigmatic example, E. coli σ70 factor (RpoD) is composed of several domains and subdomains [15][17][38][39] each of them with a specific role, namely: σ1.1, σ2 (1.2, NCR, 2.1, 2.2, 2.3 2.4), σ3 (3.0, 3.1), σ3.2 and σ4 (4.1, 4.2) (Figure 1). Once the RNAP holoenzyme has formed, domains σ1.2, σ2, σ3.1 and σ4 of the σ70 are exposed on the surface of the holoenzyme and provide the promoter recognition and binding activity (Figure 2a). Upon promoter binding, domain σ2 triggers the separation of the dsDNA at the conserved -10 motif of the promoter to form a transcription bubble or open complex [23]. Separation of the double strand is further augmented by the region σ1.2 [40][41], considered to be an extended part of the σ2 region [17], which melts the promoter at the discriminator element (details on the promoter melting capacity of the σ70 factor compared to ECFs are further explained at the end of this section). The σNCR (non-conserved region) subdomain is an adjacent region to the core σ2 domain whose interaction with the core RNAP, in a manner which is antagonistic to the core RNAP–σ2 interaction, facilitates promoter escape allowing the first stages of elongation to occur [42]. σ3.2 is a conserved linker between the σ3 and σ4 regions that inserts into the RNAP active site and occupies the RNA exit channel. Part of this region, the σ finger, interacts with the DNA template strand pre-organizing it into a helical conformation for accommodating it into the RNAP active site, thus enabling the binding of initiating NTPs to the template strand. For promoter escape and transcription elongation to occur, the DNA–σ3.2 interactions must be disrupted and the σ finger has to be displaced from the RNA exit channel, which may explain from a mechanistic perspective the close relationship between this region and abortive transcription events [23][29][43][44].

Figure 2. Comparison between the transcription initiation mechanisms of the primary σ70 factor (RpoD) and the extracytoplasmic function σ factor (ECF) RpoE, from E. coli. (a) Involvement of the different σ factor domains (using the same color code as in Figure 1) in the transcription initiation, emphasizing the differences between the vegetative σ70 factor and RpoE regarding their promoter melting capability. The different isomerization stages from closed complex to open complex are indicated. (b) Schematic of the contacts between -10 box nucleotides and σ2 domain residues for RpoD and RpoE. Residues directly interacting with -10 box nucleotides are underlined. Nucleotides that are flipped-out during transcription initiation and the respective residues that contact them are indicated in red.

References

- Mogk, A.; Tomoyasu, T.; Goloubinoff, P.; Rüdiger, S.; Röder, D.; Langen, H.; Bukau, B. Identification of thermolabile Escherichia coli proteins: Prevention and reversion of aggregation by DnaK and ClpB. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 6934–6949.

- Murata, M.; Fujimoto, H.; Nishimura, K.; Charoensuk, K.; Nagamitsu, H.; Raina, S.; Kosaka, T.; Oshima, T.; Ogasawara, N.; Yamada, M. Molecular Strategy for Survival at a Critical High Temperature in Eschierichia coli. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20063.

- Storz, G.; Tartaglia, L.A.; Ames, B.N. Transcriptional regulator of oxidative stress-inducible genes: Direct activation by oxidation. Science 1990, 248, 189–194.

- Storz, G.; Tartaglia, L.A.; Ames, B.N. The OxyR regulon. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 1990, 58, 157–161.

- Collet, J.-F.; Messens, J. Structure, Function, and Mechanism of Thioredoxin Proteins. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 13, 1205–1216.

- Fernandes, A.P.; Holmgren, A. Glutaredoxins: Glutathione-Dependent Redox Enzymes with Functions Far Beyond a Simple Thioredoxin Backup System. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2004, 6, 63–74.

- Ruchaud-Sparagano, M.H.; Maresca, M.; Kenny, B. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) inactivate innate immune responses prior to compromising epithelial barrier function. Cell. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 1909–1921.

- Galperin, M.Y. What bacteria want. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 20, 4221–4229.

- Cousin, C.; Derouiche, A.; Shi, L.; Pagot, Y.; Poncet, S.; Mijakovic, I. Protein-serine/threonine/tyrosine kinases in bacterial signaling and regulation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2013, 346, 11–19.

- Stancik, I.A.; Šestak, M.S.; Ji, B.; Axelson-Fisk, M.; Franjevic, D.; Jers, C.; Domazet-Lošo, T.; Mijakovic, I. Serine/Threonine Protein Kinases from Bacteria, Archaea and Eukarya Share a Common Evolutionary Origin Deeply Rooted in the Tree of Life. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 27–32.

- Lonetto, M.A.; Donohue, T.J.; Gross, C.A.; Buttner, M.J. Discovery of the extracytoplasmic function σ factors. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 112, 348–355.

- Staroń, A.; Sofia, H.J.; Dietrich, S.; Ulrich, L.E.; Liesegang, H.; Mascher, T. The third pillar of bacterial signal transduction: Classification of the extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factor protein family. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 74, 557–581.

- El-Gebali, S.; Mistry, J.; Bateman, A.; Eddy, S.R.; Luciani, A.; Potter, S.C.; Qureshi, M.; Richardson, L.J.; Salazar, G.A.; Smart, A.; et al. The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D427–D432.

- Pinto, D.; Liu, Q.; Mascher, T. ECF σ Factors with Regulatory Extensions: The One-Component Systems of the σ Universe. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 112, 399–409.

- Lonetto, M.; Gribskov, M.; Gross, C.A. The sigma 70 family: Sequence conservation and evolutionary relationships. J. Bacteriol. 1992, 174, 3843–3849.

- Hook-Barnard, I.G.; Hinton, D.M. Transcription Initiation by Mix and Match Elements: Flexibility for Polymerase Binding to Bacterial Promoters The Multi-Step Process of Transcription Initiation. Gene Regul. Syst. Bio. 2007, 1, 275–293.

- Paget, M.S.B. Bacterial Sigma Factors and Anti-Sigma Factors: Structure, Function and Distribution. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 1245–1265.

- Dupuy, B.; Raffestin, S.; Matamouros, S.; Mani, N.; Popoff, M.R.; Sonenshein, A.L. Regulation of toxin and bacteriocin gene expression in Clostridium by interchangeable RNA polymerase sigma factors. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 60, 1044–1057.

- Dupuy, B.; Matamouros, S. Regulation of toxin and bacteriocin synthesis in Clostridium species by a new subgroup of RNA polymerase sigma-factors. Res. Microbiol. 2006, 157, 201–205.

- MacLellan, S.R.; Guariglia-Oropeza, V.; Gaballa, A.; Helmann, J.D. A two-subunit bacterial σ-factor activates transcription inBacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 21323–21328.

- Xue, X.; Davis, M.C.; Steeves, T.; Bishop, A.; Breen, J.; MacEacheron, A.; Kesthely, C.A.; Hsu, F.; MacLellan, S.R. Characterization of a protein–protein interaction within the SigO–RsoA two-subunit σ factor: The σ70 region 2.3-like segment of RsoA mediates interaction with SigO. Microbiology 2016, 162, 1857–1869.

- Campagne, S.; Damberger, F.F.; Kaczmarczyk, A.; Francez-Charlot, A.; Allain, F.H.-T.; Vorholt, J.A. Structural basis for sigma factor mimicry in the general stress response of Alphaproteobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E1405–E1414.

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Chatterjee, S.; Tuske, S.; Ho, M.X.; Arnold, E.; Ebright, R.H. Structural Basis of Transcription Initiation. Science 2012, 338, 1076–1080.

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ebright, R.H. Structural basis of transcription activation. Science 2016, 352, 1330–1333.

- Bae, B.; Davis, E.; Brown, D.; Campbell, E.A.; Wigneshweraraj, S.; Darst, S.A. Phage T7 Gp2 inhibition of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase involves misappropriation of σ70 domain 1.1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 19772–19777.

- Naryshkin, N.; Revyakin, A.; Kim, Y.; Mekler, V.; Ebright, R.H. Structural Organization of the RNA Polymerase-Promoter Open Complex. Cell 2000, 101, 601–611.

- Mekler, V.; Kortkhonjia, E.; Mukhopadhyay, J.; Knight, J.; Revyakin, A.; Kapanidis, A.N.; Niu, W.; Ebright, Y.W.; Levy, R.; Ebright, R.H. Structural Organization of Bacterial RNA Polymerase Holoenzyme and the RNA Polymerase-Promoter Open Complex. Cell 2002, 108, 599–614.

- Hudson, B.P.; Quispe, J.; Lara-González, S.; Kim, Y.; Berman, H.M.; Arnold, E.; Ebright, R.H.; Lawson, C.L. Three-dimensional EM structure of an intact activator-dependent transcription initiation complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19830–19835.

- Murakami, K.S.; Masuda, S.; Darst, S.A. Structural Basis of Transcription Initiation: RNA Polymerase Holoenzyme at 4 A Resolution. Science 2002, 296, 1280–1284.

- Liu, X.; Bushnell, D.A.; Wang, D.; Calero, G.; Kornberg, R.D. Structure of an RNA Polymerase II–TFIIB Complex and the Transcription Initiation Mechanism. Science 2010, 327, 206–209.

- Kostrewa, D.; Zeller, M.E.; Armache, K.-J.; Seizl, M.; Leike, K.; Thomm, M.; Cramer, P. RNA polymerase II–TFIIB structure and mechanism of transcription initiation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 462, 323–330.

- Treutlein, B.; Muschielok, A.; Andrecka, J.; Jawhari, A.; Buchen, C.; Kostrewa, D.; Hög, F.; Cramer, P.; Michaelis, J. Dynamic Architecture of a Minimal RNA Polymerase II Open Promoter Complex. Mol. Cell 2012, 46, 136–146.

- Grünberg, S.; Warfield, L.; Hahn, S. Architecture of the RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex and mechanism of ATP-dependent promoter opening. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012, 19, 788–796.

- Vassylyev, D.G.; Sekine, S.-I.; Laptenko, O.; Lee, J.; Vassylyeva, M.N.; Borukhov, S.; Yokoyama, S. Crystal structure of a bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme at 2.6 A resolution. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002, 417, 712–719.

- Li, L.; Fang, C.; Zhuang, N.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y. Structural basis for transcription initiation by bacterial ECF σ factors. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–14.

- Fang, C.; Li, L.; Shen, L.; Shi, J.; Wang, S.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y. Structures and mechanism of transcription initiation by bacterial ECF factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 7094–7104.

- Lin, W.; Mandal, S.; Degen, D.; Cho, M.S.; Feng, Y.; Das, K.; Ebright, R.H. Structural basis of ECF-σ-factor-dependent transcription initiation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–14.

- Campbell, E.A.; Muzzin, O.; Chlenov, M.; Sun, J.L.; Olson, C.A.; Weinman, O.; Trester-Zedlitz, M.L.; Darst, S.A. Structure of the Bacterial RNA Polymerase Promoter Specificity sigma Subunit. Mol. Cell 2002, 9, 527–539.

- Paget, M.S.; Helmann, J.D. The σ70 family of sigma factors. Genome Biol. 2003, 4, 203.

- Haugen, S.P.; Ross, W.; Manrique, M.; Gourse, R.L. Fine structure of the promoter-sigma region 1.2 interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 3292–3297.

- Zenkin, N.; Kulbachinskiy, A.; Yuzenkova, Y.; Mustaev, A.; Bass, I.; Severinov, K.; Brodolin, K. Region 1.2 of the RNA polymerase sigma subunit controls recognition of the −10 promoter element. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 955–964.

- Leibman, M.; Hochschild, A. A sigma-core interaction of the RNA polymerase holoenzyme that enhances promoter escape. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 1579–1590.

- Basu, R.S.; Warner, B.A.; Molodtsov, V.; Pupov, D.; Esyunina, D.; Fernández-Tornero, C.; Kulbachinskiy, A.; Murakami, K.S. Structural Basis of Transcription Initiation by Bacterial RNA Polymerase Holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 24549–24559.

- Kulbachinskiy, A.; Mustaev, A. Region 3.2 of the sigma Subunit Contributes to the Binding of the 3′-Initiating Nucleotide in the RNA Polymerase Active Center and Facilitates Promoter Clearance during Initiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 18273–18276.