| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Valentina Marchica | + 3879 word(s) | 3879 | 2021-04-09 04:50:37 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 3879 | 2021-04-27 04:45:39 | | |

Video Upload Options

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a hematologic malignancy characterized by the accumulation of bone marrow (BM) clonal plasma cells, which are strictly dependent on the microenvironment.

1. Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an incurable disease characterized by the accumulation of malignant plasma cells in the bone marrow (BM) microenvironment [1]. In addition to genetic and microenvironmental alterations, MM is supported by a high degree of immune dysregulations [2][3]. Indeed, the tight relationship between MM cells and BM microenvironment cells and hypoxia, creates a permissive niche, with impaired dendritic cell (DC) differentiation and maturation, high levels of myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). Moreover, MM patients display a high percentage of regulatory T cells (Tregs), an unbalanced T helper (Th)1/Th2 cells ratio and altered functionality of natural killer (NK) cells [2]. Furthermore, an increased expression of senescent and exhaustion markers, as programmed death (PD)-1/programmed death-ligand (PD-L)1, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen (CTLA-4) and T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT) has been detected in BM immune-microenvironment of MM patients, leading to the development of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting these molecules.

Several strategies are currently used in the treatment of MM. The standard of care [4][5] includes a high dose of melphalan followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in eligible patients. Induction therapy before transplantation consists in a combined treatment with bortezomib-thalidomide or lenalidomide-dexamethasone for 4–6 cycles. Recently, the role of maintenance therapy with lenalidomide has been proved to extend the survival of MM patients. In elderly and frail patients, the combination of the proteasome inhibitor (PI) bortezomib with melphalan and prednisone or with lenalidomide and dexamethasone or the combination of lenalidomide and dexamethasone as continuous treatment are considered standard care.

The treatment of relapsed disease includes different combinations with PIs (bortezomib, carfilzomib and ixazomib), immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) (lenalidomide and pomalidomide) and dexamethasone. Moreover, both PIs and IMiDs can be combined with mAbs anti-CD38, such as daratumumab. Due to the introduction of these new drugs and transplant techniques, in the past decades, mortality of MM patients has fallen, and 5-year survival has more than doubled particularly in patients aged under 75 years [6]. However, the treatment of patients with refractory relapsed MM remains an urgent medical need due to the high incidence of refractory disease after three lines of treatment. Recently, new therapeutic strategies targeting the microenvironment have been developed, opening new perspectives in the cure of the disease including CAR-T cells, drug-conjugate mAbs and bispecific Abs [7].

Oncolytic virotherapy is an alternative therapeutic technology in cancer treatment that uses natural or genetically engineered viruses as pharmaceutical antitumor agents [8][9][10]. Tumor cells by expressing receptors or adhesion molecules on their cell surface can be targeted by viruses. Indeed, oncolytic viruses are able to selectively infect, transduce and consequently kill cancer cells without affecting normal tissue [11]. The mechanisms of action of oncolytic viruses can be direct, through selective replication within neoplastic cells, or indirect through alterations of the tumor microenvironment that lead to the induction of the antitumor immune response [12][13]. Several oncolytic viruses have shown promising results for the treatment of solid and hematological tumors [14][15][16] and the possibility of using these viruses in tumor immunotherapy has emerged in recent years [17][18]. Researchers are harnessing all the characteristics of viruses, enhancing their effect on cancer cells and awakening and activating the immune system [19].

However, despite encouraging results due to the introduction of several new drugs, recent therapies have not been shown to entirely eradicate MM and overcome drug-resistance [3][20]. Thus, novel treatment strategies are needed.

2. Direct Mechanisms of Action of Oncolytic Viruses in MM

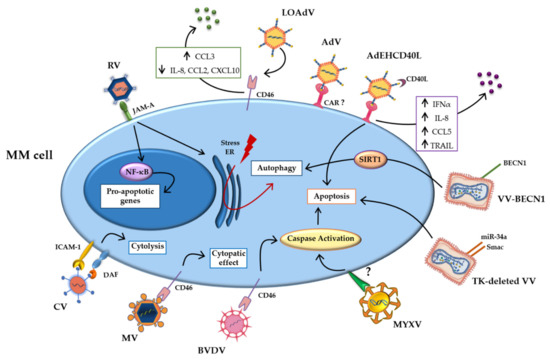

Tumor cells overexpress adhesion molecules, which bind and mediate the infection of oncolytic viruses [21][22]. Furthermore, the permissive nature of the tumor cell allows the uncontrolled replication of the genetic material and virus propagation within the malignant cell, leading to enhanced cell death [23][24]. The oncolytic viruses studied for MM treatment exploit the same mechanisms. In particular, overexpression of surface molecules, such as CD46 exploited as entry site by several viruses, and mutations in the signaling pathways make MM cells more sensitive to viral infections [25][26]. Figure 1 summarizes the main direct mechanisms.

Figure 1. Direct mechanisms of oncolytic viruses. Schematic representation of direct mechanisms of the oncolytic viruses studied in multiple myeloma (MM) cells, showing the main pathways activated by oncolytic infection. Abbreviations: AdV: Adenovirus; BECN-1: Beclin-1; BVDV: Bovine viral diarrhea virus; CAR: coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor; CCL2: Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2; CCL3: Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3; CCL5 Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5; CD40L: CD40-ligand; CXCL10: C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10; CV: Coxsakie virus; DAF: decay-accelerating factor; ER: Endoplasmic reticulum; ICAM-1: intercellular adhesion molecule; INFα: Interferonα; IL-8: Interleukin-8; JAM-A: Junctional adhesion molecule-A; LOAd: Lokon oncolytic Adenovirus; MM: Multiple myeloma; MYXV: Myxoma Virus; MV: Measles virus; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NIS: Sodium iodide symporter; RV: Reovirus; SIRT1: Sirtuin1; TK: thymidine kinase; TRAIL: TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; VV: Vaccinia Virus.

2.1. Human Viruses

The use of human viruses as a therapeutic weapon against cancer dates back to 1897 [19]. The first case reports highlighted the regression of tumors during naturally acquired viral infections [10]. In recent years, they have been genetically engineered to further attenuate their pathogenicity, increase their oncolytic potency and improve their specificity for tumor tissues. In the following paragraphs we describe the main human viruses studied for the treatment of MM.

2.1.1. Measles Virus

It has been reported that MM, as other cancer cells, overexpress CD46 compared to normal cells [27]. CD46 is the major cellular receptor for measles virus (MV) and is responsible for virus attachment, entry and cell killing through cell-cell fusion [28][29][30]. MV is an enveloped negative-sense single-stranded RNA virus in the family Paramyxoviridae with known oncolytic property [31][32]. Several studies showed that oncolytic MV replicates selectively in MM cells and its cytopathic effects correlates with CD46 levels on myeloma cells [28][33]. Peng et al. observed an antitumorigenic and antineoplastic activity of MV against human MM cells in xenografts models. Moreover, they demonstrated that MV administrated intravenously causes regression of myeloma disease [33]. Subsequently, Russell et al. reported clinical responses of 2 patients with refractory MM treated with oncolytic MV engineered to express the human thyroidal sodium iodide symporter (NIS). In particular, they demonstrated a decrease in serum free light chain (FLC) levels, a reduction of the percentage of malignant plasma cells and of extramedullary masses in both patients after a single intravenous administration of the virus [34]. A phase I study was conducted to evaluate the MV-NIS safety and maximum tolerated doses of patients with relapsed refractory MM. The selectivity of MV for the tumor has been confirmed and no toxicity has been found. Moreover, one patient achieved complete remission, while the remaining patients reported a decrease of myeloma IgG and a decrease of FLC levels [16].

2.1.2. Reovirus

Another virus with direct activity against MM is the reovirus (RV), a double-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Reoviridae family, able to exert potent antitumor activity [35][36]. The attachment and internalization of RV are mediated by junctional adhesion molecule-A (JAM-A) [37]. JAM-A is a transmembrane protein that represents an important component of tight junctions between epithelial and endothelial cells, and plays a role in tight junctions formation with a cytoskeleton [38][39]. Moreover, it has been reported that JAM-A binds directly RV and allows it to entry into cells [40]. The RV-JAM interactions are required for activation of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and induction of apoptosis during RV infection [37]. Literature data reported that JAM-A increases across the progression of MM disease [41]. Kelly et al. showed that JAM-A expression correlates with increased sensitivity to RV infection in MM cells [42]. Indeed, JAM-A expression promotes RV replication, then inducing MM cell apoptosis. In addition, RV upregulates autophagy and can trigger endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress during MM oncolysis thereby reducing tumor burden in mouse models [43][44].

2.1.3. Coxsackie Virus

Coxsackie virus (CV) is also used for oncolytic therapy. CV is non-enveloped positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus of which at least 29 strains of CV have been identified [45]. Among these, the most studied and used for virotherapy in solid and hematologic tumors is CV-A21. Its primary receptor, for attachment and internalization in the cell, is intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, which in turn interacts with decay-accelerating factor (DAF). ICAM-1 is known to mediate the interaction between MM and stromal cells, thus facilitating MM growth and survival [46]. Moreover, its expression correlates with advanced disease and resistance to chemotherapy [47]. MM cells are known to express ICAM-1 and DAF at high levels, making them the perfect target for CV-A21 oncolytic virus therapy [48]. Indeed, Au et al. demonstrated that CV-A21 induces cytolysis of MM cell lines, and its action is selective for the CD138+ cells from MM patients. Of note, it has reduced cytotoxicity in non-malignant cells. Interestingly, the authors reported the ability of CV-A21 to also eliminate premalignant plasma cells from patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), the asymptomatic precursor state of MM, suggesting the use of CV as a preventive treatment [48].

2.1.4. Adenovirus

Adenovirus (AdV) is non-enveloped double-stranded DNA extensively used for gene therapy [49]. Among its different serotypes, AdV5 is the most studied in oncolytic therapy for MM [50][51]. The receptor that allows AdV to enter and infect myeloma cells is still unknown. However, MM cells highly express the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR), which allow the entry of AdVs into mammalian cells and could probably make MM cells more susceptible [52]. On the other hand, the ability of AdV to induce cell death is well documented. Senac et al. reported that AdV5 has a high efficiency of infection in CD138+ cells from MM patients, with a high degree of specificity and selectivity for myeloma cells, thus maintaining the BM microenvironment normal cells unaltered [50]. Another study shows that AdV can be exploited for the CD40 ligand (L)-targeted delivery to MM cells. CD40L is a MM growth inhibitor [53], and binding its CD40 receptor stimulates and activates the immune system [54]. Since CD40 is expressed in different cell types, the use of CD40L vectors must be targeted to avoid non-specific immune activation. In this study, Fernandes et al. demonstrated that AdEHCD40L, an AdV armed with CD40L, inhibits MM cell growth in vitro, inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Additionally, intratumoral treatment with AdEHCD40L reduced MM cell growth in vivo in a xenograft model, leading to a reduction of tumor volume of up to 54% compared to controls [55]. A gene expression analysis was performed in order to investigate the molecular mechanism of AdEHCD40L-mediated growth inhibition in MM cells. The authors showed that interferon (IFN)-α, interleukin (IL)-8 and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL)5 were upregulated and Fas and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) [55]. Study from Wenthe et al. investigated the effect of lokon oncolytic adenovirus (LOAd), a serotype 5/35 chimera able to infect CD46+ cells, including MM cells [56]. Specifically, the authors demonstrated that LOAd infected cells are killed by oncolysis as shown by the detection of viral replication in tested human myeloma cell lines (HMCLs). Moreover, it was reported a decrease of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)10, IL-8 and CCL2 levels and the upregulation of CCL3 post LOAd infection, which could facilitate the recognition of infected MM cells by DCs. In addition, a decreased expression of costimulatory and adhesion molecules such as CD86, CD70 and ICAM-1 was observed in HMCLs infected with LOAd700 and LOAd703, which encode for CD40L and CD40L/4-1BBL respectively. On the other hand, the apoptosis receptor Fas was upregulated post virus infection. The oncolytic effect of LOAd was then confirmed in a xenograft MM model injected intratumorally [56].

2.2. Non-Human Viruses

Some human viruses due to their pathogenicity and vaccination, which would neutralize their action, cannot be considered suitable as drugs. In recent years, the attention of researchers has focused on some non-human viruses that lack pathogenicity in humans, but are still capable of destroying human tumor tissue. These viruses exploit the same entry site and mechanism of human viruses to infect and kill tumor cells. Here we reported the non-human viruses considered safe platforms for the development of anti-MM oncolytic therapy.

2.2.1. Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus

Recently, Marchica et al. demonstrated the efficiency of a bovine Pestivirus, bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), in killing MM cells [57]. BVDV is a single-stranded RNA virus considered one of the major viral pathogens of cattle, directly associated with mucosal disease [58]. BVDV binds CD46 receptor, as reported for human MV, to infect MM cells [59]. The authors showed that BVDV treatment induces apoptosis selectively in myeloma cells through the activation of Caspase-3 in vitro. Interestingly, the oncolytic effect of BVDV was increased by Bortezomib pretreatment of HMCLs. Moreover, they confirmed the oncolytic BVDV activity in an in vivo subcutaneous myeloma mouse model, which showed a reduction of tumoral burden [57].

2.2.2. Vaccinia Virus

Vaccinia virus (VV) is a linear double-stranded DNA virus, derived from the original cowpox or horsepox virus with an excellent history of safety in humans. Evidence of its oncolytic activity have been reported in in vitro studies using a VV depleted from thymidine kinase (TK) and vaccinia growth factor (VGF) to allow tumor specificity [60]. Deng et al. demonstrated that the VV cytopathic activity was specific for MM cells while no viral replication was observed in normal peripheral blood cells. The authors described a decrease of tumor volume and an increased survival of subcutaneous xenograft-bearing mice treated with VV [61]. More recently a study using two TK-deleted VV overexpressing respectively the antitumor factors, miR-34a and Smac, showed a synergistic induction of apoptosis through the activation of the caspase pathway [62]. Finally, Lei et al. have constructed a new VV overexpressing Beclin-1 gene (VV-BECN1), which induces in vitro autophagic myeloma cell death, but not apoptosis, through activation of sirtuin1 (SIRT1) [63].

2.2.3. Myxoma Virus

Myxoma Virus (MYXV) is a non-human virus, with a non-segmented double-stranded DNA genome, which showed a significant oncolytic potential against several tumors, including MM [64]. Specifically, it has been demonstrated that MYXV discriminates myeloma cells from normal cells and subsequently eliminates these cells by inducing a rapid apoptotic response mediated by caspase-8 [65]. Moreover, a study from Dunlap et al. showed that MYXV infection causes the inhibition of activating transcription factor (ATF)4, primary mediator of apoptosis during the unfolded protein response (UPR), in MM cells [66].

3. Indirect Mechanisms of Action of Oncolytic Viruses in MM

The therapeutic efficacy of oncolytic viruses can also depend on indirect activation of the immune system against the tumor cells, through the infection of microenvironmental cells, which become carriers to deliver oncolytic viruses in the tumor site [67][68]. Once infection by oncolytic viruses has occurred, cancer cells can activate an antiviral response by releasing soluble factors that stimulate immune cells [69]. Activation of immune responses induced by oncolytic viruses creates an immunogenic microenvironment that increases cell death and tumor destruction [70]. MM microenvironment is characterized by T cell imbalances, functionally defective DCs, increased MDSC percentage and upregulation of immunosuppressive checkpoint proteins [2][71][72]. These features allow MM to evade host immune surveillance. In this context, oncolytic virotherapy is currently used as an immunotherapeutic approach to increase tumor immunogenicity.

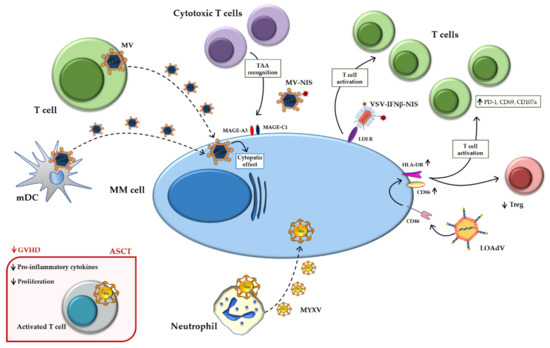

Figure 2 summarizes the main indirect mechanisms.

Figure 2. Indirect mechanisms of oncolytic viruses. Schematic representation of indirect mechanisms of oncolytic viruses using immune-microenvironment cells as carriers and active players against MM. Abbreviations: ASCT: Autologous stem cell transplantation; HLA-DR: Human leukocyte Antigen-DR isotype; GVHD: Graft versus host disease; INFβ: Interferonβ; LDLR: Low-density lipoprotein receptor; LOAd: Lokon oncolytic Adenovirus; MAGE: Melanoma antigen gene; mDCs: Mature dendritic cells; MM: Multiple myeloma; MYXV: Myxoma Virus; MV: Measles virus; NIS: Sodium iodide symporter; PD-1: Programmed death-1; TAA: Tumor-associated antigen; Treg: Regulatory T cell; VSV: Vesicular stomatitis virus.

3.1. Human Viruses

3.1.1. Measles

A study conducted by Ong et al. used activated T cells as carriers for the oncolytic virus MV [73]. In particular, T cells, isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), were loaded with previously modified MV to be directed towards the tumor sites and to escape neutralizing antibodies. Indeed, neutralizing antiviral antibodies can inhibit the anticancer activity of oncolytic viruses and in this case can prevent virus delivery to the target site. In this study, it was demonstrated that systemically administered T cells can act as carriers to deliver MV to MM subcutaneous plasmacytomas in severe combined immune deficient (SCID) mice. However, the treatment of immunized mice with MV immune serum inhibited the spread of the oncolytic MV to the tumor site. Nevertheless, oncolytic MV was detectable after the administration of serially diluted MV immune serum [73]. The authors suggest that good results can be obtained combining oncolytic therapy with plasmapheresis techniques or techniques that reduce pre-existing antiviral antibodies. Interestingly, the efficacy of MV vaccination is known to be inefficient in MM patients [74], and this could favor the use of oncolytic MV in these patients.

Other microenvironment cell types have shown promising results as virus delivery vehicles, able to access MM growth sites, such as mesenchymal progenitor cells and monocytes [75]. Peng et al. identified the presence of infiltrating CD68+, CD163+, S100- macrophages, and dispersed CD3+ T lymphocytes in plasmacytomas histologic sections from MM patients [76]. CD68+ macrophages, known as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) had a dendritic morphology and were in tight contact with several plasma cells. Since the TAMs are cells derived from monocyte lineage, isolated primary CD14+ at different stages of maturation were infected with attenuated Edmonston strain MV expressing enhanced GFP (MV-eGFP), or RFP (MV-RFP) or firefly luciferase (MV-Luc) in order to assess the ability to deliver the virus to MM cells. Mature DCs (mDCs) resulted as the most efficient cells among the different monocyte differentiation stages, while immature DCs (iDCs) showed moderate levels of infection. Subsequently, studying the biodistribution of these cells, the authors observed that the iDCs represented the best candidate to use as a vector of infection, in terms of cell viability. iDCs armed with MV were then inoculated intravenously in SCID mice, their distribution was evaluated by imaging and after 48 h of infection their presence was detected inside the tumor. These in vivo experiments showed that the survival of treated mice with iDCs as the MV carrier was significantly prolonged compared to the control group.

Recently, MV has been used as an immunotherapeutic agent to generate a persistent antitumor immune stimulation in MM patients [77]. In particular, a study by Packiriswamy et al. investigated primary T cell responses against a known panel of tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) in MM, after administration of oncolytic MV encoding sodium iodide symporter (MV-NIS) [78]. The T cell responses against the analyzed TAAs, specifically melanoma antigen gene (MAGE)-C1 and MAGE-A3, were increased after the MV-NIS treatment. Only one patient achieved complete remission with an advanced anticancer T-cell response. Another patient had mild focal relapses few months after oncolytic MV-NIS treatment, which were treated and resolved. The authors suggest that virotherapy could have potentiated the T-cell antitumor response, which was further improved after local radiotherapy treatment. Interestingly, MM patients treated with MV-NIS showed a significant increase in post-virotherapy CD3+ T lymphocytes, and this was largely due to an increase in CD8+ T cells; no changes were observed either in CD4+ T cells or in Tregs. Additionally, a more detailed analysis of the lymphocyte population showed an increased percentage of effector memory and central memory CD8+ after MV-NIS treatment, suggesting that virotherapy induced the activation of T lymphocytes.

3.1.2. Adenovirus

Besides the direct effects reported in the above paragraph, Wenthe et al. described AdV additional activity on the tumor immune-microenvironment [56]. Specifically, the authors reported the upregulation of the costimulatory molecules, CD86 and human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR isotype, on the surface of MM cells upon LOAd infection. Moreover, coculture experiments with MM cells and healthy donor PBMCs showed an expansion of central memory T cells, along with the upregulation of the activation markers CD69, PD-1 and degranulation marker CD107a, especially after infection with LOAd703. Increased levels of IFN-γ were also detected suggesting the activation of T cell compartment. On the other hand, the authors showed that the percentage of Tregs was expanded by the presence of MM cells but it decreased after LOAd infection. Together these data suggest the ability of LOAd infection to increase T cell immune activation and thus revert the immune-suppressive effect of MM cells on the immune-microenvironment [56].

3.2. Non-Human Viruses

3.2.1. Vesicular Stomatitis Virus

Among the enveloped single-stranded negative-sense RNA viruses with oncolytic activity, the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) is reported [79]. The distinguishing features of VSV are a small and easy to manipulate genome, its pantropism and the lack of pre-existing human immunity against VSV [80]. Surface molecules, such as low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR), are used by VSV for cell attachment [81]. LDLRs are ubiquitously expressed and this allows VSV to enter in different cell types [82]. However, its infection is normally inhibited by activation of protein kinase R (PKR) and IFN production [83][84]. Since the PKR system is defective in tumor cells, VSV has been shown to have a high selective lytic activity in these cells. In MM, preclinical studies have shown promising results in the use of VSV in vitro and in vivo. All reported data use genetically modified VSV to enhance its lytic effect, to monitor its infection, to improve host antitumor immunity and to maintain normal cells unaltered. In particular, a VSV able to express NIS was generated, enabling imaging and treatment with radioactive iodine. MM immunocompetent mice treated with VSV-NIS showed a reduction in the tumor burden. In addition, a further reduction was observed following treatment with radiotherapy [85]. Subsequently, Naik et al. inserted IFN-β into the VSV viral genome in order to improve the specificity of the infection and exploit the tumor immune signaling defects. Here the authors demonstrated that VSV-IFNβ has potent therapeutic efficacy against MM in immunocompetent mice, selectively and rapidly destroying tumors. Furthermore, intravenous administration of VSV-IFNβ in immunocompetent mice showed that a sufficient number of VSV-IFNβ virions reached the tumor site, carrying out its antitumor activity, and killed disseminated myeloma cells, increasing the survival of the mice. The authors suggest that IFNβ expression may promote late infiltration of immune cells into MM tumors, enhancing the antitumor immune response [86]. Subsequently, the same group determined that the optimal configuration for VSV is given by the insertion of IFNβ and NIS in its genome, to better perform its oncolytic activity. Treatment with VSV-IFNβ-NIS improved tumor reduction and survival of the mice compared with control VSV treatment. Furthermore, the immune-mediated eradication of minimal residual disease was observed in an immunocompetent MM mouse model. In fact, mice treated with VSV-IFNβ-NIS showed lower relapse rates than mice treated with VSV-IFNβ-NIS but depleted T lymphocytes [87]. Based on these results, a phase I trial was created to investigate the best dose and side effects of VSV-(h)IFNβ-NIS in the treatment of relapsed or unresponsive patients with MM, acute myeloid leukemia, or T-cell lymphoma (NCT03017820). The trial is still in the recruitment phase.

3.2.2. Myxoma Virus

An indirect effect of MYXV in MM cells has been reported in a study from Villa et al., which demonstrated that T cells exposed to MYXV are better armed to kill MM cells, thus increasing the graft-versus-tumor. The mechanism behind this effect was the transfer of active oncolytic virus to residual cancer cells. On the other hand, MYXV infects activated T cells attenuating their proliferation and production of proinflammatory cytokines thus reducing the graft-versus-host disease. Based on these results, the authors suggest that the ex vivo virotherapy with MYXV may be a promising clinical adjunct to allo-hematopoietic cell transplantation regimens [88]. Similarly, Lilly et al. demonstrated that neutrophils from BM allo-transplanted mice infected with MXYV potentially act as carrier cells to target and eradicate residual myeloma cells.

References

- Roodman, G.D. Pathogenesis of myeloma bone disease. Leukemia 2009, 23, 435–441.

- Romano, A.; Conticello, C.; Cavalli, M.; Vetro, C.; La Fauci, A.; Parrinello, N.L.; Di Raimondo, F. Immunological dysregulation in multiple myeloma microenvironment. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 198539.

- Kocoglu, M.; Badros, A. The Role of Immunotherapy in Multiple Myeloma. Pharmaceuticals 2016, 9, 3.

- Rajkumar, S.V.; Kumar, S. Multiple myeloma current treatment algorithms. Blood Cancer J. 2020, 10, 94.

- Van de Donk, N.; Pawlyn, C.; Yong, K.L. Multiple myeloma. Lancet 2021, 397, 410–427.

- Kazandjian, D. Multiple myeloma epidemiology and survival: A unique malignancy. Semin. Oncol. 2016, 43, 676–681.

- Giuliani, N.; Accardi, F.; Marchica, V.; Dalla Palma, B.; Storti, P.; Toscani, D.; Vicario, E.; Malavasi, F. Novel targets for the treatment of relapsing multiple myeloma. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2019, 12, 481–496.

- Russell, S.J.; Peng, K.W.; Bell, J.C. Oncolytic virotherapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 658–670.

- Lawler, S.E.; Speranza, M.C.; Cho, C.F.; Chiocca, E.A. Oncolytic Viruses in Cancer Treatment: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 841–849.

- Kelly, E.; Russell, S.J. History of oncolytic viruses: Genesis to genetic engineering. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2007, 15, 651–659.

- Engeland, C.E.; Bell, J.C. Introduction to Oncolytic Virotherapy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2058, 1–6.

- Cockle, J.V.; Scott, K.J. What is oncolytic virotherapy? Arch. Dis. Child.-Educ. Pract. Ed. 2018, 103, 43–45.

- Sze, D.Y.; Reid, T.R.; Rose, S.C. Oncolytic virotherapy. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2013, 24, 1115–1122.

- Bais, S.; Bartee, E.; Rahman, M.M.; McFadden, G.; Cogle, C.R. Oncolytic virotherapy for hematological malignancies. Adv. Virol. 2012, 2012, 186512.

- Li, J.L.; Liu, H.L.; Zhang, X.R.; Xu, J.P.; Hu, W.K.; Liang, M.; Chen, S.Y.; Hu, F.; Chu, D.T. A phase I trial of intratumoral administration of recombinant oncolytic adenovirus overexpressing HSP70 in advanced solid tumor patients. Gene Ther. 2009, 16, 376–382.

- Dispenzieri, A.; Tong, C.; LaPlant, B.; Lacy, M.Q.; Laumann, K.; Dingli, D.; Zhou, Y.; Federspiel, M.J.; Gertz, M.A.; Hayman, S.; et al. Phase I trial of systemic administration of Edmonston strain of measles virus genetically engineered to express the sodium iodide symporter in patients with recurrent or refractory multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2017, 31, 2791–2798.

- Tsun, A.; Miao, X.N.; Wang, C.M.; Yu, D.C. Oncolytic Immunotherapy for Treatment of Cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 909, 241–283.

- Hemminki, O.; Dos Santos, J.M.; Hemminki, A. Oncolytic viruses for cancer immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 84.

- Brown, C. Scientists are harnessing viruses to treat tumours. Nature 2020, 587, S60–S62.

- Nakamura, K.; Smyth, M.J.; Martinet, L. Cancer immunoediting and immune dysregulation in multiple myeloma. Blood 2020, 136, 2731–2740.

- Jayawardena, N.; Burga, L.N.; Poirier, J.T.; Bostina, M. Virus-Receptor Interactions: Structural Insights For Oncolytic Virus Development. Oncolytic Virother. 2019, 8, 39–56.

- Howells, A.; Marelli, G.; Lemoine, N.R.; Wang, Y. Oncolytic Viruses-Interaction of Virus and Tumor Cells in the Battle to Eliminate Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 195.

- Mohr, I. To replicate or not to replicate: Achieving selective oncolytic virus replication in cancer cells through translational control. Oncogene 2005, 24, 7697–7709.

- Singh, P.K.; Doley, J.; Kumar, G.R.; Sahoo, A.P.; Tiwari, A.K. Oncolytic viruses & their specific targeting to tumour cells. Indian J. Med. Res. 2012, 136, 571–584.

- Oliva, S.; Gambella, M.; Boccadoro, M.; Bringhen, S. Systemic virotherapy for multiple myeloma. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2017, 17, 1375–1387.

- Bartee, E. Potential of oncolytic viruses in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Oncolytic Virother. 2017, 7, 1–12.

- Liszewski, M.K.; Kemper, C. Complement in Motion: The Evolution of CD46 from a Complement Regulator to an Orchestrator of Normal Cell Physiology. J. Immunol. 2019, 203, 3–5.

- Ong, H.T.; Timm, M.M.; Greipp, P.R.; Witzig, T.E.; Dispenzieri, A.; Russell, S.J.; Peng, K.W. Oncolytic measles virus targets high CD46 expression on multiple myeloma cells. Exp. Hematol. 2006, 34, 713–720.

- Sherbenou, D.W.; Aftab, B.T.; Su, Y.; Behrens, C.R.; Wiita, A.; Logan, A.C.; Acosta-Alvear, D.; Hann, B.C.; Walter, P.; Shuman, M.A.; et al. Antibody-drug conjugate targeting CD46 eliminates multiple myeloma cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 4640–4653.

- Russell, S.J.; Peng, K.W. Measles virus for cancer therapy. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2009, 330, 213–241.

- Rota, P.A.; Moss, W.J.; Takeda, M.; de Swart, R.L.; Thompson, K.M.; Goodson, J.L. Measles. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16049.

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Yadava, P.K. Measles virus: Background and oncolytic virotherapy. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2018, 13, 58–62.

- Peng, K.W.; Ahmann, G.J.; Pham, L.; Greipp, P.R.; Cattaneo, R.; Russell, S.J. Systemic therapy of myeloma xenografts by an attenuated measles virus. Blood 2001, 98, 2002–2007.

- Russell, S.J.; Federspiel, M.J.; Peng, K.W.; Tong, C.; Dingli, D.; Morice, W.G.; Lowe, V.; O’Connor, M.K.; Kyle, R.A.; Leung, N.; et al. Remission of disseminated cancer after systemic oncolytic virotherapy. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 926–933.

- Norman, K.L.; Lee, P.W. Reovirus as a novel oncolytic agent. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 105, 1035–1038.

- Kim, M.; Chung, Y.H.; Johnston, R.N. Reovirus and tumor oncolysis. J. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 187–192.

- Barton, E.S.; Forrest, J.C.; Connolly, J.L.; Chappell, J.D.; Liu, Y.; Schnell, F.J.; Nusrat, A.; Parkos, C.A.; Dermody, T.S. Junction adhesion molecule is a receptor for reovirus. Cell 2001, 104, 441–451.

- Bazzoni, G. The JAM family of junctional adhesion molecules. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003, 15, 525–530.

- Martin-Padura, I.; Lostaglio, S.; Schneemann, M.; Williams, L.; Romano, M.; Fruscella, P.; Panzeri, C.; Stoppacciaro, A.; Ruco, L.; Villa, A.; et al. Junctional adhesion molecule, a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that distributes at intercellular junctions and modulates monocyte transmigration. J. Cell Biol. 1998, 142, 117–127.

- Antar, A.A.; Konopka, J.L.; Campbell, J.A.; Henry, R.A.; Perdigoto, A.L.; Carter, B.D.; Pozzi, A.; Abel, T.W.; Dermody, T.S. Junctional adhesion molecule-A is required for hematogenous dissemination of reovirus. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5, 59–71.

- Solimando, A.G.; Brandl, A.; Mattenheimer, K.; Graf, C.; Ritz, M.; Ruckdeschel, A.; Stuhmer, T.; Mokhtari, Z.; Rudelius, M.; Dotterweich, J.; et al. JAM-A as a prognostic factor and new therapeutic target in multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2018, 32, 736–743.

- Kelly, K.R.; Espitia, C.M.; Zhao, W.; Wendlandt, E.; Tricot, G.; Zhan, F.; Carew, J.S.; Nawrocki, S.T. Junctional adhesion molecule-A is overexpressed in advanced multiple myeloma and determines response to oncolytic reovirus. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 41275–41289.

- Kelly, K.R.; Espitia, C.M.; Mahalingam, D.; Oyajobi, B.O.; Coffey, M.; Giles, F.J.; Carew, J.S.; Nawrocki, S.T. Reovirus therapy stimulates endoplasmic reticular stress, NOXA induction, and augments bortezomib-mediated apoptosis in multiple myeloma. Oncogene 2012, 31, 3023–3038.

- Thirukkumaran, C.M.; Shi, Z.Q.; Luider, J.; Kopciuk, K.; Gao, H.; Bahlis, N.; Neri, P.; Pho, M.; Stewart, D.; Mansoor, A.; et al. Reovirus modulates autophagy during oncolysis of multiple myeloma. Autophagy 2013, 9, 413–414.

- Bradley, S.; Jakes, A.D.; Harrington, K.; Pandha, H.; Melcher, A.; Errington-Mais, F. Applications of coxsackievirus A21 in oncology. Oncolytic Virother. 2014, 3, 47–55.

- Hideshima, T.; Mitsiades, C.; Tonon, G.; Richardson, P.G.; Anderson, K.C. Understanding multiple myeloma pathogenesis in the bone marrow to identify new therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 585–598.

- Schmidmaier, R.; Morsdorf, K.; Baumann, P.; Emmerich, B.; Meinhardt, G. Evidence for cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance of multiple myeloma cells in vivo. Int. J. Biol. Markers 2006, 21, 218–222.

- Au, G.G.; Lincz, L.F.; Enno, A.; Shafren, D.R. Oncolytic Coxsackievirus A21 as a novel therapy for multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 2007, 137, 133–141.

- Wold, W.S.; Toth, K. Adenovirus vectors for gene therapy, vaccination and cancer gene therapy. Curr. Gene Ther. 2013, 13, 421–433.

- Senac, J.S.; Doronin, K.; Russell, S.J.; Jelinek, D.F.; Greipp, P.R.; Barry, M.A. Infection and killing of multiple myeloma by adenoviruses. Hum. Gene Ther. 2010, 21, 179–190.

- Raus, S.; Coin, S.; Monsurro, V. Adenovirus as a new agent for multiple myeloma therapies: Opportunities and restrictions. Korean J. Hematol 2011, 46, 229–238.

- Bergelson, J.M. Receptors mediating adenovirus attachment and internalization. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999, 57, 975–979.

- Tong, A.W.; Seamour, B.; Chen, J.; Su, D.; Ordonez, G.; Frase, L.; Netto, G.; Stone, M.J. CD40 ligand-induced apoptosis is Fas-independent in human multiple myeloma cells. Leuk. Lymphoma 2000, 36, 543–558.

- Dotti, G.; Savoldo, B.; Takahashi, S.; Goltsova, T.; Brown, M.; Rill, D.; Rooney, C.; Brenner, M. Adenovector-induced expression of human-CD40-ligand (hCD40L) by multiple myeloma cells. A model for immunotherapy. Exp. Hematol. 2001, 29, 952–961.

- Fernandes, M.S.; Gomes, E.M.; Butcher, L.D.; Hernandez-Alcoceba, R.; Chang, D.; Kansopon, J.; Newman, J.; Stone, M.J.; Tong, A.W. Growth inhibition of human multiple myeloma cells by an oncolytic adenovirus carrying the CD40 ligand transgene. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 4847–4856.

- Wenthe, J.; Naseri, S.; Hellstrom, A.C.; Wiklund, H.J.; Eriksson, E.; Loskog, A. Immunostimulatory oncolytic virotherapy for multiple myeloma targeting 4-1BB and/or CD40. Cancer Gene Ther. 2020, 27, 948–959.

- Marchica, V.; Franceschi, V.; Vescovini, R.; Storti, P.; Vicario, E.; Toscani, D.; Zorzoli, A.; Airoldi, I.; Dalla Palma, B.; Campanini, N.; et al. Bovine pestivirus is a new alternative virus for multiple myeloma oncolytic virotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 89.

- Lindberg, A.; Houe, H. Characteristics in the epidemiology of bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) of relevance to control. Prev. Veter Med. 2005, 72, 55–73.

- Maurer, K.; Krey, T.; Moennig, V.; Thiel, H.J.; Rumenapf, T. CD46 is a cellular receptor for bovine viral diarrhea virus. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 1792–1799.

- McCart, J.A.; Ward, J.M.; Lee, J.; Hu, Y.; Alexander, H.R.; Libutti, S.K.; Moss, B.; Bartlett, D.L. Systemic cancer therapy with a tumor-selective vaccinia virus mutant lacking thymidine kinase and vaccinia growth factor genes. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 8751–8757.

- Deng, H.; Tang, N.; Stief, A.E.; Mehta, N.; Baig, E.; Head, R.; Sleep, G.; Yang, X.Z.; McKerlie, C.; Trudel, S.; et al. Oncolytic virotherapy for multiple myeloma using a tumour-specific double-deleted vaccinia virus. Leukemia 2008, 22, 2261–2264.

- Lei, W.; Wang, S.; Yang, C.; Huang, X.; Chen, Z.; He, W.; Shen, J.; Liu, X.; Qian, W. Combined expression of miR-34a and Smac mediated by oncolytic vaccinia virus synergistically promote anti-tumor effects in Multiple Myeloma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32174.

- Lei, W.; Wang, S.; Xu, N.; Chen, Y.; Wu, G.; Zhang, A.; Chen, X.; Tong, Y.; Qian, W. Enhancing therapeutic efficacy of oncolytic vaccinia virus armed with Beclin-1, an autophagic Gene in leukemia and myeloma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 125, 110030.

- Calton, C.M.; Kelly, K.R.; Anwer, F.; Carew, J.S.; Nawrocki, S.T. Oncolytic Viruses for Multiple Myeloma Therapy. Cancers 2018, 10, 198.

- Bartee, M.Y.; Dunlap, K.M.; Bartee, E. Myxoma Virus Induces Ligand Independent Extrinsic Apoptosis in Human Myeloma Cells. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2016, 16, 203–212.

- Dunlap, K.M.; Bartee, M.Y.; Bartee, E. Myxoma virus attenuates expression of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) which has implications for the treatment of proteasome inhibitor-resistant multiple myeloma. Oncolytic Virother. 2015, 4, 1–11.

- Prestwich, R.J.; Harrington, K.J.; Pandha, H.S.; Vile, R.G.; Melcher, A.A.; Errington, F. Oncolytic viruses: A novel form of immunotherapy. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2008, 8, 1581–1588.

- Iankov, I.D.; Blechacz, B.; Liu, C.; Schmeckpeper, J.D.; Tarara, J.E.; Federspiel, M.J.; Caplice, N.; Russell, S.J. Infected cell carriers: A new strategy for systemic delivery of oncolytic measles viruses in cancer virotherapy. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2007, 15, 114–122.

- Bommareddy, P.K.; Shettigar, M.; Kaufman, H.L. Integrating oncolytic viruses in combination cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 498–513.

- Chaurasiya, S.; Chen, N.G.; Fong, Y. Oncolytic viruses and immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018, 51, 83–90.

- Ratta, M.; Fagnoni, F.; Curti, A.; Vescovini, R.; Sansoni, P.; Oliviero, B.; Fogli, M.; Ferri, E.; Della Cuna, G.R.; Tura, S.; et al. Dendritic cells are functionally defective in multiple myeloma: The role of interleukin-6. Blood 2002, 100, 230–237.

- Malek, E.; de Lima, M.; Letterio, J.J.; Kim, B.G.; Finke, J.H.; Driscoll, J.J.; Giralt, S.A. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: The green light for myeloma immune escape. Blood Rev. 2016, 30, 341–348.

- Ong, H.T.; Hasegawa, K.; Dietz, A.B.; Russell, S.J.; Peng, K.W. Evaluation of T cells as carriers for systemic measles virotherapy in the presence of antiviral antibodies. Gene Ther. 2007, 14, 324–333.

- Robertson, J.D.; Nagesh, K.; Jowitt, S.N.; Dougal, M.; Anderson, H.; Mutton, K.; Zambon, M.; Scarffe, J.H. Immunogenicity of vaccination against influenza, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type B in patients with multiple myeloma. Br. J. Cancer 2000, 82, 1261–1265.

- Munguia, A.; Ota, T.; Miest, T.; Russell, S.J. Cell carriers to deliver oncolytic viruses to sites of myeloma tumor growth. Gene Ther. 2008, 15, 797–806.

- Peng, K.W.; Dogan, A.; Vrana, J.; Liu, C.; Ong, H.T.; Kumar, S.; Dispenzieri, A.; Dietz, A.B.; Russell, S.J. Tumor-associated macrophages infiltrate plasmacytomas and can serve as cell carriers for oncolytic measles virotherapy of disseminated myeloma. Am. J. Hematol. 2009, 84, 401–407.

- Meyers, D.E.; Thakur, S.; Thirukkumaran, C.M.; Morris, D.G. Oncolytic virotherapy as an immunotherapeutic strategy for multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2017, 7, 640.

- Packiriswamy, N.; Upreti, D.; Zhou, Y.; Khan, R.; Miller, A.; Diaz, R.M.; Rooney, C.M.; Dispenzieri, A.; Peng, K.W.; Russell, S.J. Oncolytic measles virus therapy enhances tumor antigen-specific T-cell responses in patients with multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2020, 34, 3310–3322.

- Hastie, E.; Grdzelishvili, V.Z. Vesicular stomatitis virus as a flexible platform for oncolytic virotherapy against cancer. J. Gen. Virol. 2012, 93, 2529–2545.

- Felt, S.A.; Grdzelishvili, V.Z. Recent advances in vesicular stomatitis virus-based oncolytic virotherapy: A 5-year update. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 2895–2911.

- Finkelshtein, D.; Werman, A.; Novick, D.; Barak, S.; Rubinstein, M. LDL receptor and its family members serve as the cellular receptors for vesicular stomatitis virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 7306–7311.

- Van de Sluis, B.; Wijers, M.; Herz, J. News on the molecular regulation and function of hepatic low-density lipoprotein receptor and LDLR-related protein 1. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2017, 28, 241–247.

- Lee, S.B.; Bablanian, R.; Esteban, M. Regulated expression of the interferon-induced protein kinase p68 (PKR) by vaccinia virus recombinants inhibits the replication of vesicular stomatitis virus but not that of poliovirus. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 1996, 16, 1073–1078.

- Stojdl, D.F.; Lichty, B.; Knowles, S.; Marius, R.; Atkins, H.; Sonenberg, N.; Bell, J.C. Exploiting tumor-specific defects in the interferon pathway with a previously unknown oncolytic virus. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 821–825.

- Goel, A.; Carlson, S.K.; Classic, K.L.; Greiner, S.; Naik, S.; Power, A.T.; Bell, J.C.; Russell, S.J. Radioiodide imaging and radiovirotherapy of multiple myeloma using VSV(Delta51)-NIS, an attenuated vesicular stomatitis virus encoding the sodium iodide symporter gene. Blood 2007, 110, 2342–2350.

- Naik, S.; Nace, R.; Barber, G.N.; Russell, S.J. Potent systemic therapy of multiple myeloma utilizing oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus coding for interferon-beta. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012, 19, 443–450.

- Naik, S.; Nace, R.; Federspiel, M.J.; Barber, G.N.; Peng, K.W.; Russell, S.J. Curative one-shot systemic virotherapy in murine myeloma. Leukemia 2012, 26, 1870–1878.

- Villa, N.Y.; Wasserfall, C.H.; Meacham, A.M.; Wise, E.; Chan, W.; Wingard, J.R.; McFadden, G.; Cogle, C.R. Myxoma virus suppresses proliferation of activated T lymphocytes yet permits oncolytic virus transfer to cancer cells. Blood 2015, 125, 3778–3788.