| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maite Muniesa | + 4466 word(s) | 4466 | 2021-04-12 08:09:59 | | | |

| 2 | Lily Guo | Meta information modification | 4466 | 2021-04-12 10:25:25 | | | | |

| 3 | Lily Guo | Meta information modification | 4466 | 2021-04-12 10:26:00 | | | | |

| 4 | Lorena Rodriguez-Rubio | Meta information modification | 4466 | 2021-04-12 10:56:51 | | |

Video Upload Options

Shiga toxins (Stx) of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) are generally encoded in the genome of lambdoid bacteriophages, which spend the most time of their life cycle integrated as prophages in specific sites of the bacterial chromosome. Upon spontaneous induction or induction by chemical or physical stimuli, the stx genes are co-transcribed together with the late phase genes of the prophages. After being assembled in the cytoplasm, and after host cell lysis, mature bacteriophage particles are released into the environment, together with Stx. As members of the group of lambdoid phages, Stx phages share many genetic features with the archetypical temperate phage Lambda, but are heterogeneous in their DNA sequences due to frequent recombination events. In addition to Stx phages, the genome of pathogenic STEC bacteria may contain numerous prophages, which are either cryptic or functional. These prophages may carry foreign genes, some of them related to virulence, besides those necessary for the phage life cycle.

1. Introduction

Soon after the first reported outbreak with pathogenic Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) O157:H7 (syn. enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC)) in Oregon and Michigan, USA, in 1983, the ability of these pathogens to produce Stx (syn. Shiga-like toxin, verocytotoxin, verotoxin) was demonstrated to be encoded by bacteriophages [1]. Following this observation, Alison O’Brien’s group genetically and morphologically characterized two Stx converting phages induced from E. coli O26 and E. coli O157:H7 strains [2]. Phages H19J and 933J showed a typical head-tail structure with short tails. Some years later, Huang et al. demonstrated the homology of Stx1-converting bacteriophage H19-B to phage lambda by southern blot hybridization and restriction analysis [3]. During the following years, methodological developments allowed for an accurate characterization of Stx phages, making it clear that these phages comprise a family of genetically heterogeneous members [4][5][6][7][8][9]. Whole genome sequencing yielded the sequence data of hundreds of pathogenic STEC genomes in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/browse#!/prokaryotes/167/, accessed on 26 March 2021), which confirmed the heterogeneity of Stx phage genomes. These differences, in turn, influence the bacterial genome structure and its functionality [10]. Furthermore, the prophage sequences demonstrate that all Stx phages conserve a basic lambdoid structure that is discussed below.

2. Morphology, Genetic Structure and Integration Sites of Stx Phages

All known Stx phages are double-stranded DNA-phages with a functional genetic organization similar to that of the archetypical phage lambda, which is one of the best studied E. coli phages [11][12]. Stx phages share a common head-tail structure ranging from icosahedral or elongated heads to contractile, non-contractile, or short tails with or without tail fibers [9][13][14][15][16][17][18][19].

Although all Stx phages share the same lambda-like genetic structure, significant variations in their genetic composition occur and genome sizes ranging from 28.7 to 71.9 kb have been described [17][20][21][22].

According to their morphological structure, Stx phages are classified into different families of the order Caudovirales. For example, the Stx2a phage 933W of the E. coli O157:H7 strain EDL933 consists of a short tail and regular hexagonal head and belongs to the Podoviridae family [18], whereas the prototype Stx1 phage H19-B [3][15] consists of an elongated head with a long non-contractile tail compatible with phages of the Siphoviridae family. While most of the characterized Stx2 phages belong to the family Podoviridae [9][23][24], only a few reports exist where Stx phages have been described as members of the family Myoviridae [25].

A large majority of short-tailed Stx phages (among them the Stx2 phages 933W and Sp5 of E. coli O157 strains EDL933 and Sakai) use highly conserved tail spike proteins for host recognition [23]. Sequence homologues of the tail spike protein gene of short-tailed Stx phages were also found in the genomes of Stx phages of the Siphoviridae and Myoviridae family [26]. Essential for phage adsorption is the highly conserved receptor protein YaeT (also known as BamA) on the bacterial cell surface and its orthologues, which ensure the spread among various members of the family of Enterobacteriaceae [23][27]. Two other potential receptor proteins, FadL and LamB, have been described for phages Stx2Φ-I and Stx2Φ-II, isolated from clinical STEC strains [28], but they could not be confirmed in later studies as functional receptors for phage Sp5 of the E. coli O157 strain Sakai [27].

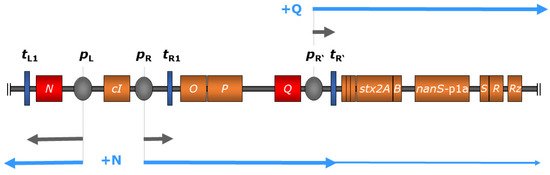

As lambdoid phages, Stx phages share a general genetic structure with immediate early, delayed early, and late phase genes. All of them possess a common regulatory system that includes different variants of cro, cI, N, and Q genes, which are involved in the regulation of the phage entering the lysogenic or lytic life cycle [19][20][29][30]. All Stx phages known so far show a conserved location of the stx genes in the late regulatory region of the prophage genomes (Figure 1) [8][11][19][31][32]. More precisely, stx genes are located downstream of the gene encoding the antiterminator protein Q and upstream of the lysis cassette consisting of S, R, and Rz, and are thereby under control of the late promoter pR’ [7][8][18][19][33] (Figure 1). However, the genomic region between the antiterminator Q gene and stx has been shown to be diverse among Stx phages of the same subtype, and is therefore supposed to have an influence on the Stx expression level [34]. Variations of the Q gene have also been reported, which are thought to have a minor impact on Stx expression and correlate loosely with a clinical or bovine origin of the strains [35]. It is hypothesized that Q21 genes similar to the one of φ21 are often associated with lower Stx expression than the Q933 gene variants of phage 933W [36][37]. Nevertheless, these results are not completely clear and could not be supported by other studies [38]. Most probably, there are various unidentified factors also contributing to the level of Stx expression [35][38].

Figure 1. Regulation scheme of stx expression in bacteriophage 933W of E. coli O157:H7 strain EDL 933 comprising relevant genes (colored in orange) and regulatory elements (not to scale), modified from Wagner and Waldor 2002 [30]. During the lysogenic state (indicated in grey arrows), transcription is inhibited through binding of the cI-encoded repressor protein to operator sites of the early promoters pL and pR (colored in grey); transcription is also terminated by downstream terminators (dark blue). Upon phage induction, autocleavage of the cI-encoded repressor protein allows transcription at pL, resulting in the production of phage-encoded antiterminator protein N (red), which enables polymerase read-through at downstream terminators including tL1 and tR1. This, in turn, leads to the expression of the late-phase antiterminator Q (red), which facilitates transcription initiating at the late-phase promoter pR’, transcending terminator tR’, and resulting in the expression of downstream genes including stx (indicated in light blue arrows). Additionally, the expression of O- and P-encoded phage replication products leads to increased Stx production by amplifying stx copy numbers [30][39].

Genomic differences have also been reported for the early regulatory regions of Stx phages. For example, Stx2 phage 933W contains three operator sites in the right operator region, but only two operator sites in the left operator region, which is different from phage lambda and most other lambdoid phages [39]. In contrast, Stx1 phage H-19B contains four operator sites in the right operator region [40]. It is not well understood how these differences in the early regulatory region affect repressor/operator interactions and, thereby, expression of Stx. However, it was demonstrated that spontaneous induction occurs more readily in Stx phages than in lambdoid prophages without stx genes [39][41].

During the lysogenic state, transcription of most phage genes is mostly silenced by the CI repressor binding at the operators within the early regulatory region [42]. Although expression of certain Stx phage genes during the lysogenic state has been reported [43], it was attributed to a small subset of cells that spontaneously induced the lytic cycle. Thereby, the transcription of phage genes is terminated at tR’ located directly downstream of pR’, thus preventing the transcription of stx genes. Upon phage induction, a cascade of regulatory events leads to the expression of early and late antiterminator proteins N and Q, respectively, allowing polymerase read-through of downstream terminators [30] (Figure 1).

Interestingly, a continuous transcription activity at phage late promoter pR’, which is terminated directly downstream at tR’, generates a short RNA byproduct under lysogenic conditions [44]. It was demonstrated that this regulatory small RNA represses expression of Stx1 under lysogenic conditions and modulates host fitness [45].

Stx phages can harbor a number of additional genes acquired by horizontal gene transfer [9][20]. These so-called morons (“more-on” refers to additional DNA on the phage genomes) are mainly found in the late phage region and usually have a different nucleotide composition compared to the rest of the phage genome. Furthermore, morons may have their own promoter and terminator sequences, so the transcription is independent from phage induction. These genes have no obvious function for the phage but are typically beneficial for the host [9][46].

The STEC genome can contain various Stx prophages and diverse non-Stx prophages [47]. Several strains naturally carry more than one Stx phage and double, or even triple, lysogens of the same Stx phage can be experimentally produced [48][49]. Stx phage integrases seem to have evolved to recognize different insertion sites within the bacterial chromosome. Thus, although each Stx phage integrates preferentially in one particular site, the integrase is able to recognize secondary sites for the phage genome integration if this preferred site is occupied or deleted [50].

Several chromosomal insertion sites have been described for Stx phages: yehV encoding a regulator for curli expression [51][52], wrbA encoding the Trp repressor-binding protein [18], yecE whose function is unknown [32], sbcB encoding an exonuclease [17][53], Z2577 encoding an oxidoreductase [54], ssrA encoding a tmRNA [55], prfC encoding a peptide chain release factor [56], argW encoding a tRNA [57], and the intergenic region between torS and torT genes [56]. In addition, a study by Steyert et al. revealed five novel insertion sites (potC, yciD, ynfH, serU, yjbM) in Locus of Enterocyte Effacement (LEE)-negative STEC isolates that had not been reported to be occupied by Stx phages before [58]. Several new insertion sites have been described for Stx phages carrying the novel Stx2 subtypes Stx2h and Stx2k [21][59]. The Stx2k prophage was found to be integrated adjacent to the yjjG, encoding a nucleotide phosphatase [59][60]. Different insertion sites were described for the Stx2k phages including dusA, which encodes a tRNA dihydroxyuridine synthase A [61], yccA, a predicted transmembrane protein [62][63], and the zur gene encoding a zinc uptake regulator [21][64].

Unlike phage lambda, Stx phages can occur as multiple isogenic prophages in the bacterial chromosome at different insertion sites [50][65]. Whereas phage lambda leads to host immunity, Stx phages are able to evade superinfection immunity [48][49][66]. For example, Stx2 phage Φ24B was shown to integrate into a single host at least three times and furthermore, it was demonstrated that the frequency of multiple lysogens increased with each integrated prophage [9][67]. Different results were reported concerning the influence of multiple lysogens on the toxin expression level: interestingly, experiments with a double isogenic Stx2 phage showed an enhanced production level of Stx [65], whereas other studies with two different Stx2 prophages showed reduced toxin levels [48][68].

3. Induction, Expression and Release of Stx

When Stx phages choose the lysogenic pathway, phage DNA is inserted into the E. coli chromosome, forming a prophage that is replicated together with the bacterial chromosome, transferred to the bacterial progeny by vertical gene transfer and maintained for many cell generations. When diverse environmental conditions threaten the viability of the bacterial cell, these stimuli trigger the SOS response, activating the induction of the prophage. Several of these stimuli have been identified including changes in pH, particularly low pH [69], presence of iron [70], presence (or absence) of ions, which also confers a role on chelating agents such as EDTA and sodium citrate [71][72], several antibiotics including growth promoters [73][74], and other agents causing DNA damage such as mitomycin C or hydrogen peroxide [75][76][77].

After induction, prophages are excised from the chromosome. The viral DNA, which exists as a separate molecule within the bacterial cell, then replicates separately from the host bacterial DNA as an extrachromosomal element [78]. It has been found that stx can be detected in a circular, extrachromosomal state when the non-chromosomal elements are analyzed by southern blot after a PFGE of S1-digested DNA from STEC strains [79]. Moreover, circularized plasmid-like pseudolysogens of Stx phages have been observed in studies of integration of Stx phage Φ24B [67]. Plasmids derived from Stx phages have also been used to study the efficiency of DNA replication of lambdoid phages [78].

During replication, expression of the phage structural proteins and Stx takes place. The structural components are assembled into new Stx phage particles, which are released from the cell by the action of phage lytic proteins expressed at the end of the induction process. These proteins cause the disruption of the bacterial host cell, allowing the release and spread of Stx [8][42], which is the main virulence factor determining the severity and lethality of the STEC infection [80].

Stx can also be released by outer membrane vesicles (OMV) [81][82][83][84]. These OMVs protect Stx and other proteins from degradation by proteases and mask its presence in cytotoxicity or bead-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays [81]. It was shown that OMVs from the hypervirulent O104:H4 outbreak strain are also internalized by intestinal epithelial cells despite not expressing the typical GB3 receptor [84]. A major study by Bielaszewska et al. also described this internalization strategy. Briefly, vesicles were taken up via dynamin-dependent endocytosis, followed by retrograde transport of the Stx holotoxin in early endosomes toward the Golgi complex and endoplasmatic reticulum. The enzymatic active Stx2A subunit could then be transported to the cytosol and bind to the ribosome [83].

In addition to Stx release, the new Stx phages are set free, which allows the dissemination and acquisition of the stx gene among susceptible cells (E. coli or even other genera) present in the same biome [85], contributing to the evolution of STEC [86]. In this context, stx genes have been detected in Citrobacter freundii [87], Enterobacter cloacae [88], Shigella sonnei [89], and Aeromonas spp. [90].

The effective production of Stx2 is always dependent on phage induction, whereas Stx release is dependent on cell lysis [42]. However, a different situation can be observed for Stx1, encoded by Stx1 phages [58][70][91]. The expression of Stx1 is caused by two independent promoters. The first is a late phage promoter pR’ dependent on phage induction (as for Stx2 phages), which allows the expression and release of the toxin by the phage-mediated cell lysis. The second is a specific Stx1 promoter containing a binding site for Fur protein, which makes complexes with iron. Thus, in the presence of iron, Fur blocks Stx1 expression, while in the absence of iron, this repression does not occur and Stx1 is expressed. This situation is entirely independent of phage induction, and Stx1 levels of production are similar to those observed under conditions where the Stx1 phage is not induced [70]. The main consequence of the phage-independent expression of Stx1 is that cells expressing Stx1 can avoid cell lysis, enhancing their survival. Fewer strains producing Stx1 phages means a lower occurrence of free Stx1 phages compared with Stx2 phages, which has been confirmed by analyzing free Stx1 vs. Stx2 phages in extracellular biomes [91].

In any case, Stx2 or Stx1 phage induction poses a serious threat for the survival of the STEC population, which must sacrifice its prevalence for the sake of increasing its virulence. The solution of the paradox presented by Stx as a virulence factor that forces phage activation and cell lysis in order to be expressed and released, is obtained when considering the heterogeneity of the STEC population. In a bacterial population, not all bacterial cells behave synchronously since they are not in the same physiological or growth state, therefore not all of them activate phage induction simultaneously. Thus, one subpopulation will induce Stx phages, producing new virions and expressing the toxin, while another subpopulation remains in the lysogenic state, enhancing its survival and becoming the population’s reservoir [92]. Although the mechanism dealing with the differences between the inducible and the non-inducible stage have not yet been completely elucidated, the growth state seems to play a role. Cells reaching the stationary phase prevent induction better than cells in the exponential phase. The RpoS factor, highly expressed in E. coli cells in the stationary phase, was shown to cause a dramatic delay in Stx phage induction within the E. coli population, and overexpression of RpoS resulted in a large number of E. coli cells that do not induce the Stx prophage [92]. In contrast, in E. coli, lambda prophage induction has been shown to be regulated by the OxyR protein [93].

The differential induction of Stx phages within the STEC population is indeed considered an altruistic strategy shown by a fraction of the STEC cells, rendering the expression of Stx a positive force for the benefit of the whole population [94]. It has been seen in cells spontaneously inducing Stx phages [41] under natural conditions but also in the presence of H2O2, which is produced by neutrophiles during STEC infection in the human body [94].

4. Stx Phages as Pathogenic Principle

In addition to stx, many additional genes have been described in Stx prophage genomes, which may contribute to pathogenicity and virulence, but also to the competitiveness with other gut bacteria in the human host. There are a number of reviews and book chapters that have described the role of some genes in the Stx phages that contribute to regulating pathogenicity in STEC [9][10][46][71][95], and therefore, their structure, function, and roles in pathogenicity will not be reviewed here.

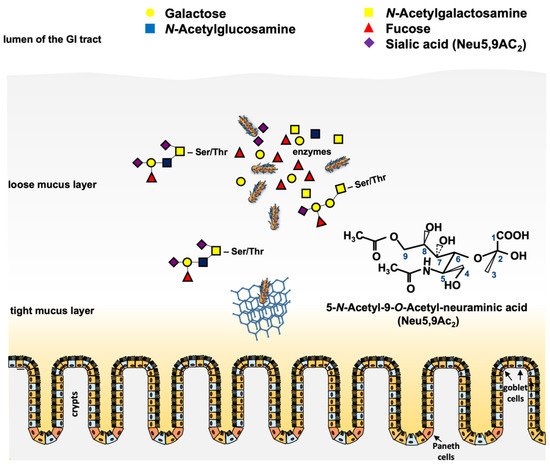

However, there is one newer gene family that is worth describing, since it is present in a number of Stx and non-Stx phages of pathogenic STEC. In preliminary work, an open reading frame (ORF) located downstream of the stx operon in the genome of phage 933W of E. coli O157:H7 and other relevant STEC serotypes was identified [96]. This ORF (z1466) could be induced in microarray experiments together with stx upon norfloxacin treatment of E. coli O157:H7 strain EDL933 [97]. When cultured in simulated colonic environmental medium (SCEM), a 40-fold expression of the corresponding protein P42 was observed [98]. Comparative analyses showed that the gene z1466 is highly homologous to a Neu5,9Ac2-esterase gene from E. coli that has already been in the focus of several studies [99][100]. By molecular and biochemical analyses, it was shown that z1466 indeed encodes a Neu5,9Ac2-acetylesterase, with an active esterase function similar to the chromosomally-encoded NanS, present in many E. coli strains [101]. Moreover, the gene was significantly longer than nanS and contained regions without homology to any known genes [102]. The function of the esterase as well as the role of seven vs. 10 Neu5,9Ac2 acetylesterases (NanS-p) from E. coli O157:H7 strain EDL933, and of five NanS-ps from E. coli O104:H4 strains C227-11φcu were analyzed, and it was shown that all these enzymes were encoded in prophage genomes that produced active esterases from their corresponding nanS-p alleles [101][103]. These results were in concordance with Eric Vimr’s early work [99] showing that cleavage of the O-acetyl residues from Neu5,9Ac2 allowed the lysogen to grow with Neu5,9Ac2 as a single carbon source. Furthermore, experiments with bovine maxillary gland mucin revealed the cleavage of mono, di, and triacetylated O-glycans by the NanS-p enzymes [102]. Similar experiments with the 2011 outbreak strain O104:H4 C227-11φcu revealed comparable results [103]. Taken together, the experiments have shown that these phage-encoded NanS-p enzymes can be used by pathogenic STEC strains to utilize mucin components for their growth, conferring an advantage to the lysogens [100][102][103][104] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Scheme of putative functions of the phage-encoded O-acetyl esterase in the large intestine. Pathogenic STEC cells have to traverse the loose and the tight mucus layer to reach the epithelium for adherence and colonization. Mucinases and other proteases play a role in that process. Cleavage of O-acteyl residues from terminal O-glycans (e.g., Neu5,9Ac2) by chromosomal and phage-encoded O-acetyl esterases results in deacetylated free sialic acids such as N-acetyl neuraminic acid, which can be metabolized by the bacteria [105]. The chemical structure of Neu5,9Ac2 is shown. Honeycomb structure = mucin network. Paneth cells and goblet cells are indicated.

The fact that nanS-p genes are generally located in phage genomes and that Neu5,9-O-acteylesterases are able to cleave O-acetyl residues from sugar moieties [106] raises the question whether this enzyme may play a role in the phage replication cycle itself and consequently could contribute to the STEC infection process. A very interesting aspect of the NanS-p function came from the structural annotation by homology modeling of the esterase domain and crystal structure analysis of the C-terminal domain of the conserved carbohydrate esterase vb_24B_21 from the Stx phage φ24B, which is homologous to nanS-p [104]. The authors proposed a lectin-like, jelly-roll sandwich-fold in the C-terminus with a proposed function in carbohydrate-binding for this domain [104]. It was hypothesized that such a structure could target the enzyme to its substrate to increase the local concentration and to improve catalysis, as shown for similar enzymes [107][108]. Up to now, there is no experimental evidence that this is the case for NanS-ps of pathogenic E. coli. However, carbohydrate-binding may be advantageous for pathogenic E. coli, which can use mucins with a particular carbohydrate structure as the substrate.

Another possibility is that NanS-ps could also be an advantage for the phages itself by enhancing the recognition of phage receptors at the bacterial outer membrane surface. In Gram-negative bacteria, phages have to encounter the LPS, which may function as an initial binding site for infection [109][110][111]. O-antigens of the lipopolysaccharide may be acetylated, and cleavage of these O-acetyl groups may facilitate phage binding [110][112] as well as subsequent traversing of the LPS to reach the specific receptor sites located at the outer membrane [113]. Whether NanS-ps may play a role for the attachment of Stx phages remains to be elucidated.

5. New Stx Phages

Aside from the two main immunologically distinct toxin types Stx1 and Stx2 [114], several subtypes have been described according to the nomenclature proposed by Scheutz et al. [115]. Whereas Stx1 presents the more homogeneous group consisting of subtypes Stx1a, Stx1c, and Stx1d, the Stx2 group is more heterogeneous and also more frequently associated with severe forms of diseases such as hemorrhagic colitis or HUS [116][117]. Additionally, the level of Stx expression has been shown to be correlated with different Stx subtypes and phages [118]. In a study by Fitzgerald et al., using an E. coli O157 strain harboring both Stx2a and Stx2c phages, it was demonstrated that Stx2a was induced more rapidly and to higher levels than Stx2c [119]. Whereas Stx2c phages seem to be highly homogeneous, as reported by Ogura et al., during a comprehensive analysis of Stx2 phages in 123 EHEC O157 strains, Stx2a phages could further be subtyped according to their replication proteins. The respective Stx2a subtypes also correlated with the level of Stx2a expression in the host strains [68].

In addition to the well-known subtypes Stx2a, Stx2b, Stx2c, Stx2d, Stx2e, Stx2f, and Stx2g, several phages harboring new stx subtypes were described. For example, the novel Stx2 subtype h, which was found in STEC strains isolated from intestinal tracts of healthy marmots in China. The Stx2h prophage was reported to be 49,713 bp in size [59]. Sequence analysis revealed 93 predicted coding sequences (CDSs), out of which 37 were hypothetical proteins or mobile elements with unknown function, while phage-specific genes, encoding proteins responsible for integration, transcriptional regulation, and lysis, were found in accordance to other Stx2 phages [59].

A further Stx2 subtype, Stx2i, was described in STEC isolates recovered from shrimps and bivalves, but no further information concerning the genomic characteristics of the respective phages was given [120][121]. The same applies to the subtype Stx2j, which was mentioned in a publication by Yang et al., but without further information [21]. The latest subtype described so far, Stx2k, was identified in E. coli strains isolated from different sources in China including humans, animals, and raw meat [21]. Interestingly, the isolated E. coli strains, which carried the Stx2k phage, showed considerable heterogeneity in serotype, genome sequence, and virulence gene profile. One of the analyzed STEC strains even harbored the plasmid-encoded heat-stable enterotoxin gene sta as well as two copies of enterotoxin gene stb, which were located on the chromosome. As the presence of these enterotoxins is characteristic for enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), they reveal an STEC/ETEC hybrid pathotype and point out the contribution of phages to the rise of new virulent bacteria. Similar results were found for the Stx2k-converting phages of these strains as they also showed considerable heterogeneity concerning insertion sites, genetic content, and structure as well as in stx expression level and cytotoxicity. The phage genome sizes ranged from 28,694 bp to 54,005 bp, with predicted CDSs between 53 and 86.

6. Structure and Function of Non-Stx Phages of Pathogenic STEC

Aside from Stx phages, other non-Stx prophages are found in the genome of STEC, some of them including complete and inducible phages, but also non-inducible, remnant, cryptic, or residual phages. Polylysogeny is therefore a very common occurrence in STEC strains, and a good example is O157 strain Sakai, which carries up to 18 different prophages [13]. As temperate phages, prophages preferentially belong to the Siphoviridae or Podoviridae morphological types [122] and usually display a modular structure, the so-called genetic mosaicism [123]. Similar sequences are also shared by different phages. For this reason, it is difficult to distinguish between Stx and non-Stx phages in the STEC complete genomes because these similar sequences confound the software used for contigs assembly, producing false chimeras. This problem is overcome when using sequencing platforms that generate longer reads [47], or by inducing and isolating the prophages before sequencing [10].

Nevertheless, the abundance of prophages in STEC strains suggests some advantage for the actors implicated, that is, bacteria and phages. Bacteria seem to keep all this prophage pool to incorporate new genetic traits [124], but also to enhance the mobilization of their genome [13][125] or, as mentioned in the previous section, confer fitness and improve growth, or regulate other elements.

Prophages coexisting in a bacterial genome also take advantage of polylysogeny, increasing their genetic diversity. Multiple recombination events between prophages located in the same genome might occur [16][124], mainly between the identical fragments of DNA shared by the co-existing prophages. These shared sequences serve to anchor the activity of recombinases, which in many cases are encoded by the prophage genomes themselves [126] or that can be provided by the host. For example, new Stx1 phages are generated after recombination events occurring between the Stx1 and Stx2 prophages [13].

Other genetic elements can interact with prophages, for example, by taking their capsids to mobilize themselves; in E. coli, this fact has been described for genomic islands [127], defective prophages [14][128][129], and plasmids [130].

8. Final Remarks

The study of Stx phages in the field of pathogenic STEC has contributed to understand that phages play a pivotal role on the virulence mechanisms of this pathogen. Moreover the study of Stx phages can serve as a model to better understand the contribution of phages to bacterial physiology and metabolism and finally, to the development of human diseases.

References

- Scotland, S.M.; Smith, H.R.; Willshaw, G.A.; Rowe, B. Vero cytotoxin production in strain of Escherichia coli is determined by genes carried on bacteriophage. Lancet 1983, 322, 216.

- O’Brien, A.D.; Newland, J.W.; Miller, S.F.; Holmes, R.K.; Smith, H.W.; Formal, S.B. Shiga-like toxin-converting phages from Escherichia coli strains that cause hemorrhagic colitis or infantile diarrhea. Science 1984, 226, 694–696.

- Huang, A.; Friesen, J.; Brunton, J.L. Characterization of a bacteriophage that carries the genes for production of Shiga-like toxin 1 in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1987, 169, 4308–4312.

- Datz, M.; Janetzki-Mittmann, C.; Franke, S.; Gunzer, F.; Schmidt, H.; Karch, H. Analysis of the enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 DNA region containing lambdoid phage gene p and shiga-like toxin structural genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996, 62, 791–797.

- Friedman, D.I.; Court, D.L. Bacteriophage lambda: Alive and well and still doing its thing. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2001, 4, 201–207.

- Johansen, B.K.; Wasteson, Y.; Granum, P.E.; Brynestad, S. Mosaic structure of Shiga-toxin-2-encoding phages isolated from Escherichia coli O157:H7 indicates frequent gene exchange between lambdoid phage genomes. Microbiology 2001, 147, 1929–1936.

- Karch, H.; Schmidt, H.; Janetzki-Mittmann, C.; Scheef, J.; Kroger, M. Shiga toxins even when different are encoded at identical positions in the genomes of related temperate bacteriophages. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1999, 262, 600–607.

- Neely, M.N.; Friedman, D.I. Functional and genetic analysis of regulatory regions of coliphage H- 19B: Location of shiga-like toxin and lysis genes suggest a role for phage functions in toxin release. Mol. Microbiol. 1998, 28, 1255–1267.

- Smith, D.L.; Rooks, D.J.; Fogg, P.C.; Darby, A.C.; Thomson, N.R.; McCarthy, A.J.; Allison, H.E. Comparative genomics of Shiga toxin encoding bacteriophages. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 311.

- Zuppi, M.; Tozzoli, R.; Chiani, P.; Quiros, P.; Martinez-Velazquez, A.; Michelacci, V.; Muniesa, M.; Morabito, S. Investigation on the evolution of Shiga toxin-converting phages based on whole genome sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11.

- Campbell, A. Comparative molecular biology of lambdoid phages. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1994, 48, 193–222.

- Casjens, S.R.; Hendrix, R.W. Bacteriophage lambda: Early pioneer and still relevant. Virology 2015, 479–480, 310–330.

- Asadulghani, M.; Ogura, Y.; Ooka, T.; Itoh, T.; Sawaguchi, A.; Iguchi, A.; Nakayama, K.; Hayashi, T. The defective prophage pool of Escherichia coli O157: Prophage-prophage interactions potentiate horizontal transfer of virulence determinants. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, 1000408.

- García-Aljaro, C.; Ballesté, E.; Muniesa, M. Beyond the canonical strategies of horizontal gene transfer in prokaryotes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017, 38, 95–105.

- Muniesa, M.; Schmidt, H. Shiga toxin-encoding phages: Multifunctional gene ferries. Pathog. Escherichia coli Mol. Cell Mikrobiol. 2014, 57–77.

- Ogura, Y.; Ooka, T.; Iguchi, A.; Toh, H.; Asadulghani, M.; Oshima, K.; Kodama, T.; Abe, H.; Nakayama, K.; Kurokawa, K.; et al. Comparative genomics reveal the mechanism of the parallel evolution of O157 and non-O157 enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 17939–17944.

- Ohnishi, M.; Terajima, J.; Kurokawa, K.; Nakayama, K.; Murata, T.; Tamura, K.; Ogura, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Hayashi, T. Genomic diversity of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli 0157 revealed by whole genome PCR scanning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 17043–17048.

- Plunkett, G.; Rose, D.J.; Durfee, T.J.; Blattner, F.R. Sequence of Shiga toxin 2 phage 933W from Escherichia coli O157:H7: Shiga toxin as a phage late-gene product? J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 1767–1778.

- Schmidt, H. Shiga-toxin-converting bacteriophages. Res. Microbiol. 2001, 152, 687–695.

- Krüger, A.; Lucchesi, P.M.A. Shiga toxins and stx phages: Highly diverse entities. Microbiology 2015, 161, 1–12.

- Yang, X.; Bai, X.; Zhang, J.; Sun, H.; Fu, S.; Fan, R.; He, X.; Scheutz, F.; Matussek, A.; Xiong, Y. Escherichia coli strains producing a novel Shiga toxin 2 subtype circulate in China. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 310.

- Yara, D.A.; Greig, D.R.; Gally, D.L.; Dallman, T.J.; Jenkins, C. Comparison of Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages in highly pathogenic strains of shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the UK. Microb. Genom. 2020, 6.

- Smith, D.L.; James, C.E.; Sergeant, M.J.; Yaxian, Y.; Saunders, J.R.; McCarthy, A.J.; Allison, H.E. Short-tailed Stx phages exploit the conserved YaeT protein to disseminate Shiga toxin genes among enterobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 7223–7233.

- Muniesa, M.; Blanco, J.E.; de Simón, M.; Serra-Moreno, R.; Blanch, A.R.; Jofre, J. Diversity of stx2 converting bacteriophages induced from Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from cattle. Microbiology 2004, 150, 2959–2971.

- Rooks, D.J.; Libberton, B.; Woodward, M.J.; Allison, H.E.; McCarthy, A.J. Development and application of a method for the purification of free shigatoxigenic bacteriophage from environmental samples. J. Microbiol. Methods 2012, 91, 240–245.

- Smith, D.L.; Wareing, B.M.; Fogg, P.C.M.; Riley, L.M.; Spencer, M.; Cox, M.J.; Saunders, J.R.; McCarthy, A.J.; Allison, H.E. Multilocus characterization scheme for shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 8032–8040.

- Islam, M.R.; Ogura, Y.; Asadulghani, M.; Ooka, T.; Murase, K.; Gotoh, Y.; Hayashi, T. A sensitive and simple plaque formation method for the Stx2 phage of Escherichia coli O157: H7, which does not form plaques in the standard plating procedure. Plasmid 2012, 67, 227–235.

- Watarai, M.; Sato, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Shimizu, T.; Yamasaki, S.; Tobe, T.; Sasakawa, C.; Takeda, Y. Identification and characterization of a newly isolated Shiga toxin 2-converting phage from Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 52, 27.

- Herold, S.; Karch, H.; Schmidt, H. Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages--genomes in motion. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004, 294, 115–121.

- Wagner, P.L.; Waldor, M.K. Minireview bacteriophage control of bacterial virulence. Society 2002, 70, 3985–3993.

- Neely, M.N.; Friedman, D.I. Arrangement and functional identification of genes in the regulatory region of lambdoid phage H-19B, a carrier of a Shiga-like toxin. Gene 1998, 223, 105–113.

- Recktenwald, J.; Schmidt, H. The nucleotide sequence of Shiga toxin (Stx) 2e-encoding phage φP27 is not related to other Stx phage genomes, but the modular genetic structure is conserved. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 1896–1908.

- Wagner, P.L.; Neely, M.N.; Zhang, X.; Acheson, D.W.K.; Waldor, M.K.; Friedman, D.I. Role for a phage promoter in Shiga toxin 2 expression from a pathogenic Escherichia coli strain. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 2081–2085.

- Zhang, L.X.; Simpson, D.J.; McMullen, L.M.; Gänzle, M.G. Comparative genomics and characterization of the late promoter pR′ from shiga toxin prophages in Escherichia coli. Viruses 2018, 10, 595.

- LeJeune, J.T.; Abedon, S.T.; Takemura, K.; Christie, N.P.; Sreevatsan, S. Human Escherichia coli O157:H7 genetic marker in isolates of bovine origin. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1482–1485.

- Matsumoto, M.; Suzuki, M.; Takahashi, M.; Hirose, K.; Minagawa, H.; Ohta, M. Identification and epidemiological description of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 strains producing low amounts of Shiga toxin 2 in Aichi Prefecture, Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 61, 442–445.

- Koitabashi, T.; Vuddhakul, V.; Radu, S.; Morigaki, T.; Asai, N.; Nakaguchi, Y.; Nishibuchi, M. Genetic characterization of Escherichia coli O157:H7/- strains carrying the stx2 gene but not producing shiga toxin 2. Microbiol. Immunol. 2006, 50, 135–148.

- Olavesen, K.K.; Lindstedt, B.A.; Løbersli, I.; Brandal, L.T. Expression of Shiga toxin 2 (Stx2) in highly virulent Stx-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) carrying different anti-terminator (q) genes. Microb. Pathog. 2016, 97, 1–8.

- Tyler, J.S.; Mills, M.J.; Friedman, D.I. The operator and early promoter region of the Shiga toxin type 2-encoding bacteriophage 933W and control of toxin expression. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 7670–7679.

- Shi, T.; Friedman, D.I. The operator-early promoter regions of Shiga-toxin bearing phage H-19B. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 41, 585–599.

- Livny, J.; Friedman, D.I. Characterizing spontaneous induction of Stx encoding phages using a selectable reporter system. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 51, 1691–1704.

- Waldor, M.K.; Friedman, D.I. Phage regulatory circuits and virulence gene expression. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2005, 8, 459–465.

- Riley, L.M.; Veses-Garcia, M.; Hillman, J.D.; Handfield, M.; McCarthy, A.J.; Allison, H.E. Identification of genes expressed in cultures of E. coli lysogens carrying the Shiga toxin-encoding prophage ψ24 B. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 42.

- Tree, J.J.; Granneman, S.; McAteer, S.P.; Tollervey, D.; Gally, D.L. Identification of bacteriophage-encoded anti-sRNAs in pathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Cell 2014, 55, 199–213.

- Sy, B.M.; Lan, R.; Tree, J.J. Early termination of the Shiga toxin transcript generates a regulatory small RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 25055–25065.

- Hendrix, R.W.; Lawrence, J.G.; Hatfull, G.F.; Casjens, S. The origins and ongoing evolution of viruses. Trends Microbiol. 2000, 8, 504–508.

- Shaaban, S.; Cowley, L.A.; McAteer, S.P.; Jenkins, C.; Dallman, T.J.; Bono, J.L.; Gally, D.L. Evolution of a zoonotic pathogen: Investigating prophage diversity in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 by long-read sequencing. Microb. Genom. 2016, 2, e000096.

- Serra-Moreno, R.; Jofre, J.; Muniesa, M. The CI repressors of Shiga toxin-converting prophages are involved in coinfection of Escherichia coli strains, which causes a down regulation in the production of Shiga toxin 2. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 4722–4735.

- Fogg, P.C.M.; Rigden, D.J.; Saunders, J.R.; McCarthy, A.J.; Allison, H.E. Characterization of the relationship between integrase, excisionase and antirepressor activities associated with a superinfecting Shiga toxin encoding bacteriophage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 2116–2129.

- Serra-Moreno, R.; Jofre, J.; Muniesa, M. Insertion site occupancy by stx2 bacteriophages depends on the locus availability of the host strain chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 6645–6654.

- Creuzburg, K.; Recktenwald, J.; Kuhle, V.; Herold, S.; Hensel, M.; Schmidt, H. The Shiga toxin 1-converting bacteriophage BP-4795 encodes an NleA-like type III effector protein. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 8494–8498.

- Yokoyama, K.; Makino, K.; Kubota, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Kimura, S.; Yutsudo, C.H.; Kurokawa, K.; Ishii, K.; Hattori, M.; Tatsuno, I.; et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of the prophage VT1-Sakai carrying the Shiga toxin 1 genes of the enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain derived from the Sakai outbreak. Gene 2000, 258, 127–139.

- Strauch, E.; Hammerl, J.A.; Konietzny, A.; Schneiker-Bekel, S.; Arnold, W.; Goesmann, A.; Pühler, A.; Beutin, L. Bacteriophage 2851 is a prototype phage for dissemination of the Shiga toxin variant gene 2c in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 5466–5477.

- Koch, C.; Hertwig, S.; Appel, B. Nucleotide sequence of the integration site of the temperate bacteriophage 6220, which carries the Shiga toxin gene stx1ox3. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 6463–6466.

- Creuzberg, K.; Köhler, B.; Hempel, H.; Schreier, P.; Jacobs, E.; Schmidt, H. Genetic structure and chromosomal integration site of the cryptic prophage CP-1639 encoding Shiga toxin 1. Microbiology 2005, 151, 941–950.

- Ogura, Y.; Ooka, T.; Asadulghani; Terajima, J.; Nougayrède, J.P.; Kurokawa, K.; Tashiro, K.; Tobe, T.; Nakayama, K.; Kuhara, S.; et al. Extensive genomic diversity and selective conservation of virulence-determinants in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli strains of O157 and non-O157 serotypes. Genome Biol. 2007, 8.

- Kulasekara, B.R.; Jacobs, M.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, Z.; Sims, E.; Saenphimmachak, C.; Rohmer, L.; Ritchie, J.M.; Radey, M.; McKevitt, M.; et al. Analysis of the genome of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 2006 spinach-associated outbreak isolate indicates candidate genes that may enhance virulence. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 3713–3721.

- Steyert, S.R.; Sahl, J.W.; Fraser, C.M.; Teel, L.D.; Scheutz, F.; Rasko, D.A. Comparative genomics and stx phage characterization of LEE-negative Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 133.

- Bai, X.; Fu, S.; Zhang, J.; Fan, R.; Xu, Y.; Sun, H.; He, X.; Xu, J.; Xiong, Y. Identification and pathogenomic analysis of an Escherichia coli strain producing a novel Shiga toxin 2 subtype. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8.

- Titz, B.; Häuser, R.; Engelbrecher, A.; Uetz, P. The Escherichia coli protein YjjG is a house-cleaning nucleotidase in vivo. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007, 270, 49–57.

- Farrugia, D.N.; Elbourne, L.D.H.; Mabbutt, B.C.; Paulsen, I.T. A novel family of integrases associated with prophages and genomic islands integrated within the tRNA-dihydrouridine synthase A (dusA) gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 4547–4557.

- Perna, N.T.; Iii, G.P.; Burland, V.; Mau, B.; Glasner, J.D.; Rose, D.J.; Mayhew, G.F.; Po, È.; Evans, P.S.; Gregor, J.; et al. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 2001, 409, 529–533.

- Vanderhaeghen, S.; Zehentner, B.; Scherer, S.; Neuhaus, K.; Ardern, Z. The novel EHEC gene asa overlaps the TEGT transporter gene in antisense and is regulated by NaCl and growth phase. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17875.

- Lim, C.K.; Hassan, K.A.; Penesyan, A.; Loper, J.E.; Paulsen, I.T. The effect of zinc limitation on the transcriptome of Pseudomonas protegens Pf-5. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 702–715.

- Fogg, P.C.M.; Saunders, J.R.; Mccarthy, A.J.; Allison, H.E. Cumulative effect of prophage burden on Shiga toxin production in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 2012, 158, 488–497.

- Allison, H.E.; Sergeant, M.J.; James, C.E.; Saunders, J.R.; Smith, D.L.; Sharp, R.J.; Marks, T.S.; McCarthy, A.J. Immunity profiles of wild-type and recombinant Shiga-like toxin-encoding bacteriophages and characterization of novel double lysogens. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 3409–3418.

- Fogg, P.C.M.; Gossage, S.M.; Smith, D.L.; Saunders, J.R.; McCarthy, A.J.; Allison, H.E. Identification of multiple integration sites for Stx-phage Φ24B in the Escherichia coli genome, description of a novel integrase and evidence for a functional anti-repressor. Microbiology 2007, 153, 4098–4110.

- Ogura, Y.; Mondal, S.I.; Islam, M.R.; Mako, T.; Arisawa, K.; Katsura, K.; Ooka, T.; Gotoh, Y.; Murase, K.; Ohnishi, M.; et al. The Shiga toxin 2 production level in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 is correlated with the subtypes of toxin-encoding phage. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16663.

- Kimmitt, P.T.; Harwood, C.R.; Barer, M.R. Toxin gene expression by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: The role of antibiotics and the bacterial SOS response. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2000, 6, 458–465.

- Wagner, P.L.; Livny, J.; Neely, M.N.; Acheson, D.W.K.; Friedman, D.I.; Waldor, M.K. Bacteriophage control of Shiga toxin 1 production and release by Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 44, 957–970.

- Lenzi, L.J.; Lucchesi, P.M.A.; Medico, L.; Burgán, J.; Krüger, A. Effect of the food additives sodium citrate and disodium phosphate on shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and production of stx-phages and Shiga toxin. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 992.

- Imamovic, L.; Muniesa, M. Characterizing RecA-independent induction of Shiga toxin2-encoding phages by EDTA treatment. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32393.

- Maiques, E.; Úbeda, C.; Campoy, S.; Salvador, N.; Lasa, Í.; Novick, R.P.; Barbé, J.; Penadés, J.R. β-lactam antibiotics induce the SOS response and horizontal transfer of virulence factors in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 2726–2729.

- Köhler, B.; Karch, H.; Schmidt, H. Antibacterials that are used as growth promoters in animal husbandry can affect the release of Shiga-toxin-2-converting bacteriophages and Shiga toxin 2 from Escherichia coli strains. Microbiology 2000, 146, 1085–1090.

- Łoś, J.M.; Łoś, M.; Wegrzyn, G.; Wegrzyn, A. Differential efficiency of induction of various lambdoid prophages responsible for production of Shiga toxins in response to different induction agents. Microb. Pathog. 2009, 47, 289–298.

- Łoś, J.M.; Łoś, M.; Wȩgrzyn, A.; Wȩgrzyn, G. Hydrogen peroxide-mediated induction of the Shiga toxin-converting lambdoid prophage ST2-8624 in Escherichia coli O157:H7. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2010, 58, 322–329.

- Fang, Y.; Mercer, R.G.; McMullen, L.M.; Gänzle, M.G. Induction of Shiga toxin-encoding prophage by abiotic environmental stress in food. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01378-17.

- Nejman, B.; Nadratowska-Wesołowska, B.; Szalewska-Pałasz, A.; Wȩgrzyn, A.; Wȩgrzyn, G. Replication of plasmids derived from Shiga toxin-converting bacteriophages in starved Escherichia coli. Microbiology 2011, 157, 220–233.

- Muniesa, M.; (Department of Genetics, Microbiology and Statistics, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain). Personal communication, 2021.

- Balasubramanian, S.; Osburne, M.S.; BrinJones, H.; Tai, A.K.; Leong, J.M. Prophage induction, but not production of phage particles, is required for lethal disease in a microbiome-replete murine model of enterohemorrhagic E. coli infection. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, 1–27.

- Yokoyama, K.; Horii, T.; Yamashino, T.; Hashikawa, S.; Barua, S.; Hasegawa, T.; Watanabe, H.; Ohta, M. Production of Shiga toxin by Escherichia coli measured with reference to the membrane vesicle-associated toxins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000, 192, 139–144.

- Kolling, G.L.; Matthews, K.R. Export of virulence genes and Shiga toxin by membrane vesicles of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 1843–1848.

- Bielaszewska, M.; Rüter, C.; Bauwens, A.; Greune, L.; Jarosch, K.A.; Steil, D.; Zhang, W.; He, X.; Lloubes, R.; Fruth, A.; et al. Host cell interactions of outer membrane vesicle-associated virulence factors of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157: Intracellular delivery, trafficking and mechanisms of cell injury. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13.

- Kunsmann, L.; Ruter, C.; Bauwens, A.; Greune, L.; Gluder, M.; Kemper, B.; Fruth, A.; Wai, S.N.; He, X.; Lloubes, R.; et al. Virulence from vesicles: Novel mechanisms of host cell injury by Escherichia coli O104:H4 outbreak strain. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13252.

- Khalil, R.K.S.; Skinner, C.; Patfield, S.; He, X. Phage-mediated Shiga toxin (Stx) horizontal gene transfer and expression in non-Shiga toxigenic Enterobacter and Escherichia coli strains. Pathog. Dis. 2016, 74.

- Eichhorn, I.; Heidemanns, K.; Ulrich, R.G.; Schmidt, H.; Semmler, T.; Fruth, A.; Bethe, A.; Goulding, D.; Pickard, D.; Karch, H.; et al. Lysogenic conversion of atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (aEPEC) from human, murine, and bovine origin with bacteriophage Φ3538 Δstx2::cat proves their enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) progeny. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2018, 308, 890–898.

- Schmidt, H.; Montag, M.; Bockemuhl, J.; Heesemann, J.; Karch, H. Shiga-like toxin II-related cytotoxins in Citrobacter freundii strains from humans and beef samples. Infect. Immun. 1993, 61, 534–543.

- Paton, A.W.; Paton, J.C. Enterobacter cloacae producing a Shiga-like toxin II-related cytotoxin associated with a case of hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996, 34, 463–465.

- Tóth, I.; Sváb, D.; Bálint, B.; Brown-Jaque, M.; Maróti, G. Comparative analysis of the Shiga toxin converting bacteriophage first detected in Shigella sonnei. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016, 37, 150–157.

- Palma-Martínez, I.; Guerrero-Mandujano, A.; Ruiz-Ruiz, M.J.; Hernández-Cortez, C.; Molina-López, J.; Bocanegra-García, V.; Castro-Escarpulli, G. Active shiga-like toxin produced by some Aeromonas spp., isolated in Mexico City. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7.

- Grau-Leal, F.; Quirós, P.; Martínez-Castillo, A.; Muniesa, M. Free Shiga toxin 1-encoding bacteriophages are less prevalent than Shiga toxin 2 phages in extraintestinal environments. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 4790–4801.

- Imamovic, L.; Ballesté, E.; Martínez-Castillo, A.; García-Aljaro, C.; Muniesa, M. Heterogeneity in phage induction enables the survival of the lysogenic population. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 957–969.

- Glinkowska, M.; Łoś, J.M.; Szambowska, A.; Czyż, A.; Całkiewicz, J.; Herman-Antosiewicz, A.; Wróbel, B.; Wȩgrzyn, G.; Węgrzyn, A.; Łoś, M. Influence of the Escherichia coli oxyR gene function on λ prophage maintenance. Arch. Microbiol. 2010, 192, 673–683.

- Loś, J.M.; Loś, M.; Wȩgrzyn, A.; Wȩgrzyn, G. Altruism of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: Recent hypothesis versus experimental results. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 1–8.

- Hernandez-Doria, J.D.; Sperandio, V. Bacteriophage transcription factor Cro regulates virulence gene expression in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 607–617.e6.

- Unkmeir, A.; Schmidt, H. Structural analysis of phage-borne stx genes and their flanking sequences in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and Shigella dysenteriae type 1 strains. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 4856–4864.

- Herold, S.; Siebert, J.; Huber, A.; Schmidt, H. Global expression of prophage genes in Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain EDL933 in response to norfloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 931–944.

- Polzin, S.; Huber, C.; Eylert, E.; Elsenhans, I.; Eisenreich, W.; Schmidt, H. Growth media simulating ileal and colonic environments affect the intracellular proteome and carbon fluxes of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157: H7 strain EDL933. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 3703–3715.

- Vimr, E.R. Unified theory of bacterial sialometabolism: How and why bacteria metabolize host sialic acids. ISRN Microbiol. 2013, 2013, 1–26.

- Rangel, A.; Steenbergen, S.M.; Vimr, E.R. Unexpected diversity of Escherichia coli sialate O-acetyl esterase NanS. J. Bacteriol. 2016, 198, 2803–2809.

- Nübling, S.; Eisele, T.; Stöber, H.; Funk, J.; Polzin, S.; Fischer, L.; Schmidt, H. Bacteriophage 933W encodes a functional esterase downstream of the Shiga toxin 2a operon. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2014, 304, 269–274.

- Saile, N.; Voigt, A.; Kessler, S.; Stressler, T.; Klumpp, J.; Fischer, L.; Schmidt, H. Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain EDL933 harbors multiple functional prophage-associated genes necessary for the utilization of 5-N-acetyl-9-O-acetyl neuraminic acid as a growth substrate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 5940–5950.

- Saile, N.; Schwarz, L.; Eissenberger, K.; Klumpp, J.; Fricke, F.W.; Schmidt, H. Growth advantage of Escherichia coli O104:H4 strains on 5-N-acetyl-9-O-acetyl neuraminic acid as a carbon source is dependent on heterogeneous phage-borne nanS-p esterases. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2018, 308, 459–468.

- Franke, B.; Veses-Garcia, M.; Diederichs, K.; Allison, H.; Rigden, D.J.; Mayans, O. Structural annotation of the conserved carbohydrate esterase vb_24B_21 from Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophage Φ24B. J. Struct. Biol. 2020, 212, 107596.

- Josenhans, C.; Müthing, J.; Elling, L.; Bartfeld, S.; Schmidt, H. How bacterial pathogens of the gastrointestinal tract use the mucosal glyco-code to harness mucus and microbiota: New ways to study an ancient bag of tricks. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 310.

- Feuerbaum, S.; Saile, N.; Pohlentz, G.; Müthing, J.; Schmidt, H. De-O-Acetylation of mucin-derived sialic acids by recombinant NanS-p esterases of Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain EDL933. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2018, 308, 1113–1120.

- Boraston, A.B.; Bolam, D.N.; Gilbert, H.J.; Davies, G.J. Carbohydrate-binding modules: Fine-tuning polysaccharide recognition. Biochem. J. 2004, 382, 769–781.

- Gilbert, H.J.; Knox, J.P.; Boraston, A.B. Advances in understanding the molecular basis of plant cell wall polysaccharide recognition by carbohydrate-binding modules. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2013, 23, 669–677.

- Kulikov, E.E.; Golomidova, A.K.; Prokhorov, N.S.; Ivanov, P.A.; Letarov, A.V. High-throughput LPS profiling as a tool for revealing of bacteriophage infection strategies. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2958.

- Prokhorov, N.S.; Riccio, C.; Zdorovenko, E.L.; Shneider, M.M.; Browning, C.; Knirel, Y.A.; Leiman, P.G.; Letarov, A.V. Function of bacteriophage G7C esterase tailspike in host cell adsorption. Mol. Microbiol. 2017, 105, 385–398.

- Kulikov, E.E.; Majewska, J.; Prokhorov, N.S.; Golomidova, A.K.; Tatarskiy, E.V.; Letarov, A.V. Effect of O-acetylation of O antigen of Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide on the nonspecific barrier function of the outer membrane. Microbiology 2017, 86, 310–316.

- Pickard, D.; Toribio, A.L.; Petty, N.K.; Van Tonder, A.; Yu, L.; Goulding, D.; Barrell, B.; Rance, R.; Harris, D.; Wetter, M.; et al. A conserved acetyl esterase domain targets diverse bacteriophages to the Vi capsular receptor of Salmonella enterica serovar typhi. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 5746–5754.

- Casjens, S.R.; Molineux, I.J. Short noncontractile tail machines: Adsorption and DNA delivery by podoviruses. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 726, 143–179.

- Strockbine, N.A.; Marques, L.R.M.; Newland, J.W.; Smith, H.W.; Holmes, R.K.; O’brien, A.D. Two toxin-converting phages from Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain 933 encode antigenically distinct toxins with similar biologic activities. Infect. Immun. 1986, 53, 135–140.

- Scheutz, F.; Teel, L.D.; Beutin, L.; Piérard, D.; Buvens, G.; Karch, H.; Mellmann, A.; Caprioli, A.; Tozzoli, R.; Morabito, S.; et al. Multicenter evaluation of a sequence-based protocol for subtyping Shiga toxins and standardizing Stx nomenclature. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 2951–2963.

- Friedrich, A.W.; Bielaszewska, M.; Zhang, W.L.; Pulz, M.; Kuczius, T.; Ammon, A.; Karch, H. Escherichia coli harboring shiga toxin 2 gene variants: Frequency and association with clinical symptoms. J. Infect. Dis. 2002, 185, 74–84.

- Persson, S.; Olsen, K.E.P.; Ethelberg, S.; Scheutz, F. Subtyping method for Escherichia coli Shiga toxin (Verocytotoxin) 2 variants and correlations to clinical manifestations. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 2020–2024.

- Fuller, C.A.; Pellino, C.A.; Flagler, M.J.; Strasser, J.E.; Weiss, A.A. Shiga toxin subtypes display dramatic differences in potency. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 1329–1337.

- Fitzgerald, S.F.; Beckett, A.E.; Palarea-Albaladejo, J.; McAteer, S.; Shaaban, S.; Morgan, J.; Ahmad, N.I.; Young, R.; Mabbott, N.A.; Morrison, L.; et al. Shiga toxin sub-type 2a increases the efficiency of Escherichia coli O157 transmission between animals and restricts epithelial regeneration in bovine enteroids. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15.

- Lacher, D.W.; Gangiredla, J.; Patel, I.; Elkins, C.A.; Feng, P.C.H. Use of the Escherichia coli identification microarray for characterizing the health risks of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from foods. J. Food Prot. 2016, 79, 1656–1662.

- Martin, C.C.; Svanevik, C.S.; Lunestad, B.T.; Sekse, C.; Johannessen, G.S. Isolation and characterisation of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from Norwegian bivalves. Food Microbiol. 2019, 84, 103268.

- Fauquet, C.M.; Fargette, D. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses and the 3142 unassigned species. Virol. J. 2005, 2, 64.

- Hatfull, G.F. Bacteriophage genomics. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2008, 11, 447–453.

- Ohnishi, M.; Kurokawa, K.; Hayashi, T. Diversification of Escherichia coli genomes: Are bacteriophages the major contributors? Trends Microbiol. 2001, 9, 481–485.

- Muniesa, M.; Colomer-Lluch, M.; Jofre, J. Could bacteriophages transfer antibiotic resistance genes from environmental bacteria to human-body associated bacterial populations? Mob. Genet. Elements 2013, 3, e25847.

- Datsenko, K.A.; Wanner, B.L. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 6640–6645.

- Fillol-Salom, A.; Bacarizo, J.; Alqasmi, M.; Ciges-Tomas, J.R.; Martínez-Rubio, R.; Roszak, A.W.; Cogdell, R.J.; Chen, J.; Marina, A.; Penadés, J.R. Hijacking the hijackers: Escherichia coli pathogenicity islands redirect helper phage packaging for their own benefit. Mol. Cell 2019, 75, 1020–1030.e4.

- De Paepe, M.; Hutinet, G.; Son, O.; Amarir-Bouhram, J.; Schbath, S.; Petit, M.A. Temperate phages acquire DNA from defective prophages by relaxed homologous recombination: The role of Rad52-like recombinases. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10.

- Tormo-Más, M.Á.; Mir, I.; Shrestha, A.; Tallent, S.M.; Campoy, S.; Lasa, Í.; Barbé, J.; Novick, R.P.; Christie, G.E.; Penadés, J.R. Moonlighting bacteriophage proteins derepress staphylococcal pathogenicity islands. Nature 2010, 465, 779–782.

- Rodríguez-Rubio, L.; Serna, C.; Ares-Arroyo, M.; Matamoros, B.R.; Delgado-Blas, J.F.; Montero, N.; Bernabe-Balas, C.; Wedel, E.F.; Mendez, I.S.; Muniesa, M.; et al. Extensive antimicrobial resistance mobilization via multicopy plasmid encapsidation mediated by temperate phages. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020.