| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deog-Hwan Oh | + 1942 word(s) | 1942 | 2021-04-01 08:23:18 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 1942 | 2021-04-02 10:58:54 | | |

Video Upload Options

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MetS) is presently an alarming public health problem globally. Oxidative stress has been postulated to be strongly correlated with MetS, such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and certain cancers. In addition, substantial evidence of the role of antioxidants in human health and chronic disease prevention exist. Cereals are important staple foods which account for a huge proportion of the human diet. However, owing to recent growing demand and the search for natural antioxidants, the development of cereal peptidic antioxidants using bioinformatics approaches, simultaneous application of green food processing technologies with enzymatic and fermentation methods could potentially be used as health-promoting functional ingredients, foods or dietary supplements for the prevention and management of MetS. However, the obtainability and achievability of human equivalent doses under physiological conditions still remains controversial and requires further studies.

1. Oxidative Stress

The term “oxidative stress” was initially conceptualized about three (3) decades ago [1][2]. Since then, the term has evolved remarkably. The inception of oxidative stress finds its roots in early publications of Seyle (loc. cit), which were concerned with the toxicity of oxygen linked with aging, bodily responses and processes associated with oxygen radicals, the concept of the physiology of the mitochondria and research on its aging, as well as work on variances of redox reactions in living organisms [1]. Table 1 shows several definitions proposed by different scientists over the years. Consequently, oxidative stress is denoted by an imbalance between oxidant and antioxidant species, such that oxidant species weigh more, which results in the excessive release of free radicals or reactive oxygen species (ROS) and causes cellular and molecular disruption, as well as a negative influence on redox signaling [3][4][5]. Oxidative stress occurs when antioxidant defenses are impaired or are not strong enough to overpower the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [3][4][6]. The consequences of oxidative stress may be progressive and often dire. The two underlying components in oxidative stress, as evidenced by the definition above, are prooxidant and antioxidant species. It is their non-homeostatic co-existence that results in oxidative stress. To prevent excess ROS production in mammalian cells, antioxidant molecules and antioxidant enzymes act as defense systems. There are many prooxidant species and antioxidant species. In cells, glutathione (GSH) is the most abundant and important non-protein antioxidant molecule. Antioxidants are those substances that counteract the harmful effects of oxidants. They are usually produced in insufficient quantities by the body; therefore, they need to be supplemented frequently from external sources, typically food sources [7]. Examples of antioxidants are vitamins A, C, E, carotenoids (including beta-carotene and astaxanthins), and polyphenols (such as flavonoids, isoflavones, anthocyanins, chlorogenic, and catechins) [7][8][9]. Examples of prooxidants, particularly the reactive species, include reactive oxygen species (ROS) [6][10], reactive sulfur species (RSS) [11], reactive electrophile species (RES) [12], reactive carbonyl species (RCS) [13][14], reactive nitrogen species (RNS) [15][16][17], and reactive halogen species (RHS) [10][15][18]. ROS, RHS, and RNS are toxic oxidants that cause damage to DNA, RNA, lipids, and phagocytosed pathogen proteins, especially during inflammation [10]. According to Yang et al. [19], ROS, RHS, and RNS cause apoptosis by directly oxidizing protein, lipid, and DNA signaling pathways, which increases the risk of CVD, specifically atherosclerosis. RSS are molecules produced from sequential one-electron oxidations (loss of electrons in a chemical reaction) of hydrogen sulfide, thus forming thiyl, hydrogen persulfide, and the persulfide “supersulfide” radicals, before terminating in elemental sulfur [11]. There are resemblances between ROS and RSS, and they are sometimes misconstrued and used interchangeably. However, RSS have more effectiveness, reactivity, signaling, and versatility potential compared to ROS. They can also be accumulated and reused [11]. RES have a wide range of functionality with overlying chemical reactivity, which sometimes makes the study of biological RES challenging. Biologically, they range in different shapes and forms. RES involved in cell signaling may even rise higher when they sense the human body is stressed. RHS control antioxidant response, cell growth, DNA damage development, aging, cellular homeostasis events, such as apoptosis, and immune response [12].

Table 1. Some proposed definitions of oxidative stress throughout the course of time.

| Definition of Oxidative Stress | Reference |

|---|---|

| Oxidative stress is a disturbance in the prooxidant–antioxidant balance in favor of the former. | [20] |

| Oxidative stress is defined as a disturbance in the prooxidant–antioxidant balance that leads to potential damage. | [21] |

| Oxidative stress is a situation when steady-state ROS concentration is transiently or chronically enhanced, disturbing cellular metabolism, its regulation, and damaging cellular constituents. | [22] |

| Oxidative stress is defined as excess production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) relative to antioxidant defense. | [23] |

| Oxidative stress refers to the imbalance between cellular antioxidant cascade and processes that generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide (O2.), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl anion (OH−). | [24] |

| Oxidative stress is defined as an imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants in favor of the oxidants, leading to a disruption of redox signaling and control and/or molecular damage. This implies a deviation to the opposite side of the balance (thus, “reductive stress”), as well as physiological and supraphysiological deviations, which tie into the overarching concept of “oxidative distress” and “oxidative eustress”, respectively. | [5] |

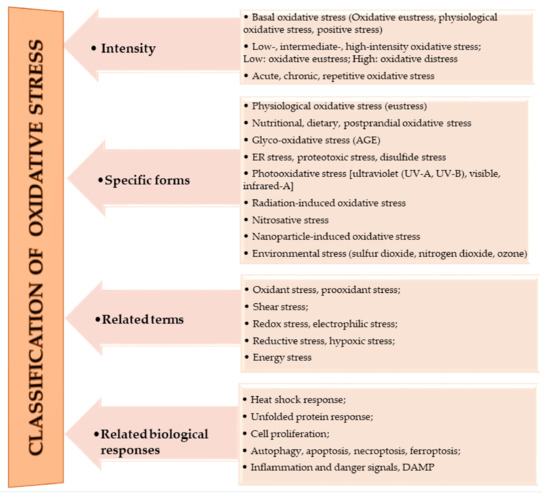

The oxidation of macromolecules, such as carbohydrates, lipids, and amino acids, produces many reactive carbonyl species (RCS). RCS can react and cause changes to the surface composition of proteins, nucleic acids and amino phospholipids, and therefore serve as agents of cell destruction and gene mutation. Furthermore, interaction of RCS with biological samples results in many chemical products that have diverse negative effects on human health [13]. RCS are shown to be involved in ROS signaling, and are typically classified under RES [14]. Electrophilic and nucleophilic reactions are some of the most common covalent bond formations that are found in many chemical–cellular reactions. The electrophilic nature of carbonyl compounds has a high affinity for nucleophilic cellular constituents, thus making it possible for easy accessibility of the cells by RCS to render its physiological effects [13][14]. In the form of free radicals, such as nitric oxide and other nitric oxide-derived species (organic species, such as 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) and S-nitrosothiols (RS–NO), and inorganic species, such as nitrite [15]), RNS are involved in a variety of biological activities, and their detection and quantification are technically difficult [15][16]. However, there is evidence that, when RNS is produced in excess, it disrupts protein synthesis in the body, which harms mitochondrial metabolism dynamics and mitophagy in the nervous system [17]. RHS, especially those with chlorine, bromine, and iodine (thus, HOX with X=Cl, Br or I) induce injuries to DNA, RNA, lipids, and proteins cells [10][15]. They render the immune system’s defense useless when they are released into the body in high quantities by reversing the action of phagocytes (including neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, mast cells, dendritic cells, osteoclasts, and eosinophils) that capture pathogens, and, thus, instigate disease or infection pathogenesis [10]. When RHS interreact with extracellular myeloperoxidase (MPO) produced by neutrophils to provide immune system defenses against pathogens, it results in tissue damage, cellular damage, and inflammatory reactions that facilitate the occurrence of a variety of diseases, particularly CVD (atherosclerosis), obesity, T2DM, and, ultimately, metabolic syndrome (MetS) [10][18]. Owing to the vast quantities and differences in prooxidant and antioxidant species, the best way to understand oxidative stress is through a classification system. According to Sies et al. [4], oxidative stress can be classified according to its intensity (basal, low, intermediate, and high), specific forms, related terms, and associated biological responses (Figure 1). A further assessment by Lushchak [22] establishes that imbalance could also result from one or a combination of the following: elevated levels of endogenous and exogenous compounds entering autoxidation, coupled with ROS production; depleted stores of low molecular mass antioxidants; deactivated antioxidant enzymes; and reduced production of antioxidant enzymes and low molecular mass antioxidants. These determine the three types of oxidative stress—acute, chronic, and quasi-stationery [22][25][26][27] (Table 2).

Figure 1. Classifications of oxidative stress adapted with permission from Sies et al. [4]. Copyright 2017 Annual Reviews, Inc.

Table 2. Types/Levels of oxidative stress.

| Oxidative Stress | Definition | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Acute | The inability of cells to neutralize enhanced ROS level over a period of time, such that the time is enough to result in specific physiological consequences. | [22][25][26][27] |

| Chronic | It occurs when acute oxidative stress progresses to significantly disturb homeostasis. Here, the ROS levels are elevated and very stable, and very potent in altering healthy cell components. | [22] |

| Quasi-stationery | It occurs when ROS levels are so elevated that it is almost impossible to return to ideal homeostatic levels, thus resulting in the need for a substantial reorganization of the entire homeostatic system. | [26][27] |

2. Metabolic Syndrome (MetS)

Insulin resistant syndrome, MetS, or dysmetabolic syndrome are other terms used to denote metabolic syndrome. MetS is a health condition characterized by the summative complexities of three or more of the following risk factors: high blood pressure, abdominal obesity, elevated triglyceride (TG) levels, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels, and high fasting levels of blood sugar that instigate the potential for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [28][29][30]. Typically, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels are less than 40 mg/dL in men, or less than 50 mg/dL in women; elevated TG is 150 mg/dL of blood or higher; elevated fasting glucose is l00 mg/dL or higher; and high blood pressure is indicated by systolic levels of 130 mmHg or higher and/or diastolic levels of 85 mmHg or higher [31]. Research purports a positive correlation between increases in age and obesity, and the prevalence of MetS [32][33]. Sigit et al. [34] argue that MetS is sex and population specific. Current trends suggest Asian populations are showing, relatively, the highest prevalence (an estimate of 39.9 ± 0.7%) [34][35]; about one-third of US adults (thus, 34.3 ± 0.8% of all adults and 50% of those aged 60 years or older) have MetS [33][36]; and about 29.2 ± 0.7% in European populations [34][35][36]. Comparatively, the prevalence is very minimal in populations in Africa; however, diabetes, one of the pre-indicators of MetS, is expected to have huge spikes in sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and North Africa (141% and 104%, respectively) in the next 25 years [30]. It is worth noting that sex and populations showed differing prevalence and contributing risk factors of MetS. For instance, in relation to sex, the incidence of MetS was higher in Indonesian women than in Indonesian men, but higher in Dutch men than in Dutch women [34]; in relation to contributing risk factors, Asian–Chinese men recorded higher TG and FBS levels than European men. Again, Chinese women recorded higher glucose levels than European women [34][37]; abdominal obesity was higher in Dutch women than in Indonesian women [34].

The Link: Oxidative Stress and Metabolic Syndrome

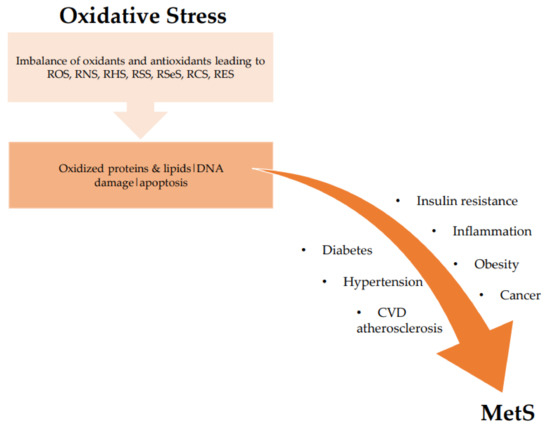

There is compelling evidence of the association between oxidative stress and MetS from both human and animal studies [38][39][40][41]. Oxidative stress correlates with increased BMI, increased adiposity, and high blood pressure, which are all components of the risk factors of MetS. Particularly in obesity-related MetS, elevated ROS production targets adipose tissue and rapidly incites fat accumulation, thereby contributing to atherosclerosis, among other vascular medical conditions [40][41][42]. Oxidative stress reduces the number of helpful proteins, such as adiponectin (involved in regulating glucose levels and fatty acid breakdown); as adiponectin decreases, systemic oxidative stress levels increase. Oxidative stress associated with increased adiposity mediates the development of MetS [38][42][43]. There are two main mechanisms by which this occurs: first, through increased oxidative stress in accumulated fat, resulting in uncontrolled adipocytokines production; and second, the selective rise in reactive species production in accumulated fat, resulting in high systemic oxidative stress [38][39][40][41]. Oxidative stress impairs pancreatic beta cells’ ability to secrete insulin, affecting glucose transport in muscle and adipocytes which relates to the development of hypertension and diabetes [38][42]. The association between oxidative stress and MetS is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Association between oxidative stress and MetS. ROS: reactive oxygen species; RNS: reactive nitrogen species; RHS: reactive halogen species; RSS: reactive sulfur species; RSeS: reactive selenium species; RCS: reactive carbonyl species; RES: reactive electrophile species; CVD: cardiovascular diseases.

References

- Breitenbach, M.; Eckl, P. Introduction to Oxidative Stress in Biomedical and Biological Research. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 1169–1170.

- Sies, H. On the history of oxidative stress: Concept and some aspects of current development. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2018, 7, 122–126.

- Salim, S. Oxidative stress and the central nervous system. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2017, 360, 201–205.

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative stress. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 715–748.

- Sies, H. Oxidative stress: Concept and some practical aspects. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 852.

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 363–383.

- Mitra, A.K. Antioxidants: A Masterpiece of Mother Nature to Prevent Illness. J. Chem. Rev. 2020, 2, 243–256.

- Rahal, A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, V.; Yadav, B.; Tiwari, R.; Chakraborty, S.; Dhama, K. Oxidative stress, prooxidants, and antioxidants: The interplay. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 761264.

- Ofosu, F.K.; Elahi, F.; Daliri, E.B.-M.; Tyagi, A.; Chen, X.Q.; Chelliah, R.; Kim, J.-H.; Han, S.-I.; Oh, D.-H. UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS characterization, antioxidant and antidiabetic properties of sorghum grains. Food Chem. 2021, 337, 127788.

- Lu, Q.-B. Reaction Cycles of Halogen Species in the Immune Defense: Implications for Human Health and Diseases and the Pathology and Treatment of COVID-19. Cells 2020, 9, 1461.

- Olson, K.R. Reactive oxygen species or reactive sulfur species: Why we should consider the latter. J. Exp. Biol. 2020, 223, jeb196352.

- Parvez, S.; Long, M.J.; Poganik, J.R.; Aye, Y. Redox signaling by reactive electrophiles and oxidants. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 8798–8888.

- Semchyshyn, H.M. Reactive carbonyl species in vivo: Generation and dual biological effects. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 417842.

- Mano, J.I.; Biswas, M.; Sugimoto, K. Reactive carbonyl species: A missing link in ROS signaling. Plants 2019, 8, 391.

- Lee, B.H.; Lopez-Hilfiker, F.D.; Veres, P.R.; McDuffie, E.E.; Fibiger, D.L.; Sparks, T.L.; Ebben, C.J.; Green, J.R.; Schroder, J.C.; Campuzano-Jost, P. Flight deployment of a high-resolution time-of-flight chemical ionization mass spectrometer: Observations of reactive halogen and nitrogen oxide species. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 7670–7686.

- Möller, M.N.; Rios, N.; Trujillo, M.; Radi, R.; Denicola, A.; Alvarez, B. Detection and quantification of nitric oxide–derived oxidants in biological systems. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 14776–14802.

- Nakamura, T.; Lipton, S.A. Nitric oxide-dependent protein post-translational modifications impair mitochondrial function and metabolism to contribute to neurodegenerative diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020, 32, 817–833.

- Davies, M.J.; Hawkins, C.L. The role of myeloperoxidase in biomolecule modification, chronic inflammation, and disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020, 32, 957–981.

- Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhang, X.; Hu, D.; Gao, Y.; Xing, Y.; Shang, H. Oxidative stress-mediated atherosclerosis: Mechanisms and therapies. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 600.

- Sies, H. (Ed.) Oxidative stress: Introductory remarks. In Oxidative Stress, 1st ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1985; pp. 1–8.

- Roede, J.R.; Stewart, B.J.; Petersen, D.R. Hepatotoxicity of Reactive Aldehydes. In Comprehensive Toxicology, 2nd ed.; McQueen, C.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, MA, USA, 2010; Volume 9, pp. 581–594.

- Lushchak, V.I. Free radicals, reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress and its classification. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2014, 224, 164–175.

- El-Fawal, H.A.N. Neurotoxicology. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Health, 1st ed.; Nriagu, J.O., Ed.; Elsevier: Burlington, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 4, pp. 87–106.

- Ofosu, F.K.; Mensah, D.J.F.; Daliri, E.B.M.; Lee, B.H.; Oh, D.H. Probiotics, diet, and gut microbiome modulation in metabolic syndromes prevention. In Advances in Probiotics Microorganisms in Food and Health; Dhanasekaran, D., Narayanan, S., Eds.; Elsievier Academic Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; in press.

- Hermes-Lima, M. Oxygen in biology and biochemistry: Role of free radicals. Funct. Metab. Regul. Adapt. 2004, 1, 319–366.

- Lushchak, V.I. Environmentally induced oxidative stress in aquatic animals. Aquat. Toxicol. 2011, 101, 13–30.

- Lushchak, V.I. Adaptive response to oxidative stress: Bacteria, fungi, plants and animals. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2011, 153, 175–190.

- Shankar, K.; Mehendale, H. Encyclopedia of toxicology. Oxidative Stress 2014, 20, 735–737.

- Grundy, S.M. Metabolic syndrome. In Diabetes Complications, Comorbidities and Related Disorders, 1st ed.; Bonora, E., DeFronzo, R.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 71–107.

- Shoushou, I.M.; Melebari, A.N.; Alalawi, H.A.; Alghaith, T.A.; Alaithan, M.S.; Albriman, M.H.A.; Hawsawi, H. Evaluation of Metabolic Syndrome in Primary Health Care. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Allied Sci. 2020, 9, 52–55.

- Swarup, S.; Goyal, A.; Grigorova, Y.; Zeltser, R. Metabolic syndrome. In Statpearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020.

- Di Daniele, N.; Petramala, L.; Di Renzo, L.; Sarlo, F.; Della Rocca, D.G.; Rizzo, M.; Fondacaro, V.; Iacopino, L.; Pepine, C.J.; De Lorenzo, A. Body composition changes and cardiometabolic benefits of a balanced Italian Mediterranean Diet in obese patients with metabolic syndrome. Acta Diabetol. 2013, 50, 409–416.

- Aguilar, M.; Bhuket, T.; Torres, S.; Liu, B.; Wong, R.J. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the United States, 2003–2012. JAMA 2015, 313, 1973–1974.

- Sigit, F.S.; Tahapary, D.L.; Trompet, S.; Sartono, E.; Van Dijk, K.W.; Rosendaal, F.R.; De Mutsert, R. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its association with body fat distribution in middle-aged individuals from Indonesia and the Netherlands: A cross-sectional analysis of two population-based studies. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2020, 12, 1–11.

- Marcos-Delgado, A.; Hernández-Segura, N.; Fernández-Villa, T.; Molina, A.J.; Martín, V. The Effect of Lifestyle Intervention on Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Metabolic Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 887.

- Shin, D.; Kongpakpaisarn, K.; Bohra, C. Trends in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components in the United States 2007–2014. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 259, 216–219.

- Lesser, I.A.; Gasevic, D.; Lear, S.A. The effect of body fat distribution on ethnic differences in cardiometabolic risk factors of Chinese and Europeans. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 38, 701–706.

- Furukawa, S.; Fujita, T.; Shimabukuro, M.; Iwaki, M.; Yamada, Y.; Nakajima, Y.; Nakayama, O.; Makishima, M.; Matsuda, M.; Shimomura, I. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 114, 1752–1761.

- Bonomini, F.; Rodella, L.F.; Rezzani, R. Metabolic syndrome, aging and involvement of oxidative stress. Aging Dis. 2015, 6, 109.

- Li, L.; Yang, X. The essential element manganese, oxidative stress, and metabolic diseases: Links and interactions. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 7580707.

- Monserrat-Mesquida, M.; Quetglas-Llabrés, M.; Capó, X.; Bouzas, C.; Mateos, D.; Pons, A.; Tur, J.A.; Sureda, A. Metabolic syndrome is associated with oxidative stress and proinflammatory state. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 236.

- Spahis, S.; Borys, J.-M.; Levy, E. Metabolic syndrome as a multifaceted risk factor for oxidative stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 26, 445–461.

- Manna, P.; Jain, S.K. Obesity, oxidative stress, adipose tissue dysfunction, and the associated health risks: Causes and therapeutic strategies. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2015, 13, 423–444.