| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yi-Wen Liu | + 2479 word(s) | 2479 | 2021-04-01 08:26:28 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | + 2704 word(s) | 2704 | 2021-04-01 09:42:02 | | |

Video Upload Options

Our previous study demonstrated that the glutathione S-transferase Mu 5 (GSTM5) gene is highly CpG-methylated in bladder cancer cells and that demethylation by 5-aza-dC activates GSTM5 gene expression. The aim of the present study was to investigate the role of GSTM5 in bladder cancer.

1. Introduction

Bladder cancer is the fourth most common type of cancer among men in the United States [1] and is the ninth most common cancer type worldwide [2]. Although bladder cancer is the 13th most lethal cancer type globally [2], its high recurrence impairs patient quality of life and results in considerable economic burden. Recently, immunotherapy has provided hope for the treatment of metastatic platinum-refractory bladder cancer but is only effective in patients with programmed cell death 1 ligand 1-positive status [3]. Therefore, it is important to prevent the development of bladder tumors by elucidating the factors involved in their carcinogenesis and progression. There are various risk factors for the development of bladder cancer, including exposure to arylamines [4], smoking [5], exposure to environmental arsenic [6][7], aging and hereditary influences. Among these factors, cigarette smoke is the single most prevalent cause of bladder cancer [8].

Gene polymorphism is also a factor for bladder cancer development. Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), a family of phase 2 detoxification enzymes, play an important role in the metabolism and/or detoxification of various endo- and xenobiotics, including drugs [9]. GSTs catalyze the conjugation of glutathione (GSH) to a wide variety of xenobiotics. This detoxification ability plays an important role in cellular protection from the environment and oxidative stress but is also implicated in cellular resistance to various chemotherapy drugs [10]. GSTs can be categorized into different families according to similarities in amino acid sequence. GSTmu (GSTM) is one of the largest GST families, which contains five members, GSTM1-M5. It is known that approximately 50% of the population possess the GSTM1-null genotype, which results in a lack of GSTM1 enzyme activity [11]. Furthermore, loss of the GSTM1 gene is known to be correlated with human bladder cancer [11][12]. Smoking also increases the odds ratio of bladder cancer in individuals with the GSTM1-null genotype [12][13]. Cigarette smoke contains various carcinogens, including nitrosamines, and the bladder carcinogen N-butyl N-(4-hydroxybutyl) nitrosamine has been shown to induce mouse bladder carcinogenesis accompanied by decreasing GSTM1 gene expression [14]. The human genome database indicates that GSTM1-M5 is located on chromosome 1 and in close proximity to each other [15]. Furthermore, genes in the same GST family have a greater opportunity to play as substitutes for one another. For example, GSTM2 has been reported to functionally compensate for GSTM1-null in Indian people [16]. Moreover, a protective genotype with higher GSTM3 expression exhibits a lower breast cancer risk when GSTM1 is absent [17].

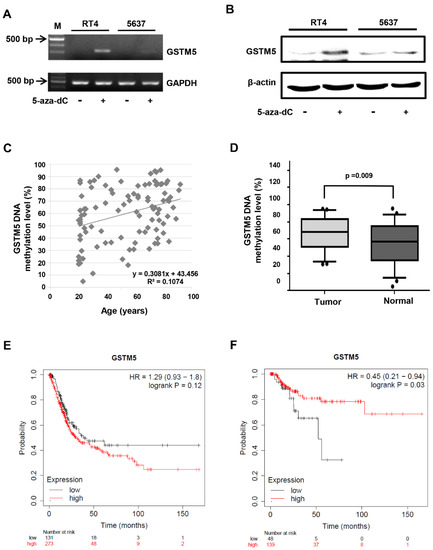

The role of GSTM2 has been studied in lung cancer, where it was found to decrease benzo[a]pyrene-induced DNA damage in lung cancer cells [18][19]. DNA methylation of the GSTM2 gene promoter decreases its gene expression by inhibiting Sp1 binding [20], and GSTM2 expression suppresses the migration of lung cancer cells [21]. A global analysis of promoter methylation in treatment-naïve urothelial cancer suggests that GSTM3 is one of the hypermethylated genes in invasive urothelial carcinoma [22]. In addition, other published reports have indicated an association between GSTM5 and cancers. A study of Barrett’s adenocarcinoma indicated that the gene expression of GSTM2, GSTM3 and GSTM5, but not GSTM4, was lower in tumors than in normal tissues and that DNA methylation also regulates gene expression [23]. In our previous study, the GSTM5 gene was found to be heavily CpG methylated and expressed at low levels in human bladder cancer cells. After treatment with the DNA methylation inhibitor 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-aza-dC), the methylation level of GSTM5 was decreased, resulting in an increase in GSTM5 gene expression in 5637 and J82 cells [24]. In the present study, the DNA methylation level of human GSTM5 was analyzed in patients with bladder cancer and normal subjects, and GSTM5 was overexpressed in bladder cancer cells to assess changes in cancer-associated characteristics.

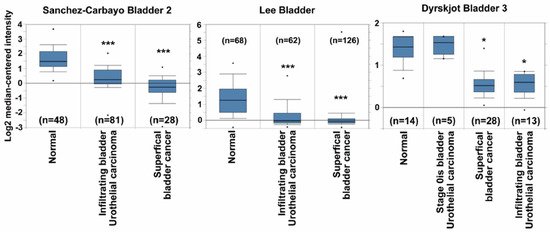

2. GSTM5 mRNA Expression Is Downregulated in Bladder Cancer Tissues

The GSTM5 mRNA expression data of patients with bladder cancer were extracted from the publicly available Oncomine database. After data-mining for GSTM5 and bladder cancer in cancer vs. normal differential analysis (p < 0.001, fold change >1.5, gene rank the top 10%), three mRNA databases exhibited differential expression (Sanchez-Carbayo bladder 2, Lee bladder and Dyrskjot bladder 3). In these three databases, GSTM5 mRNA was downregulated in superficial and infiltrating bladder tumor tissues compared with normal tissues (Figure 1), suggesting that GSTM5 may play a tumor suppressor role in human bladder cancer.

Figure 1. Glutathione S-transferase Mu 5 (GSTM5) mRNA expression is downregulated in patients with bladder cancer from the Oncomine database. Three mRNA databases exhibited different expression levels of GSTM5 mRNA between normal and cancer tissues (left panel: Sanchez-Carbayo bladder 2, middle panel: Lee bladder, right panel: Dyrskjot bladder 3). The dots are the maximum and minimum, the box contains 75% to 25% values, the line in box is median, and the lines outside the box are the values of 90% and 10%. The n means bladder sample number, * p < 1 × 10−7; *** p < 1 × 10−9 compared to normal.

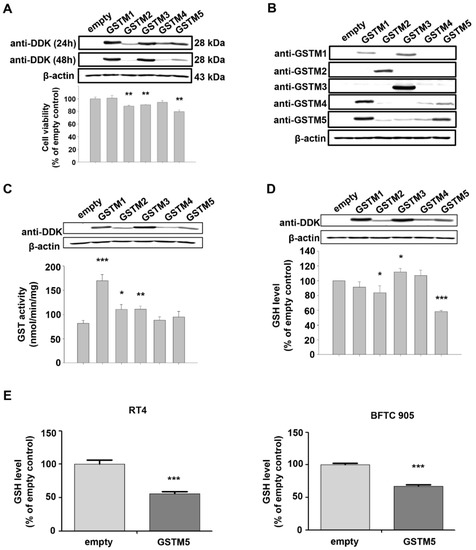

3. Biological Effects of GSTM1-5 Overexpression in Bladder Cancer Cells

In addition to GSTM5 and GSTM1, there are another 3 members in the GSTM family, including GSTM2-4. GSTM1~5 share 66 to 88% amino acid sequence similarity. GSTM2 is known to play a tumor suppressor role [21], and functional characteristics that may also be shared GSTM5 (Figure 1); therefore, the effects of GSTM1-5 on cell viability were compared by overexpressing these proteins in 5637 cells. GSTM1-5 were transiently overexpressed in 5637 cells and detected by anti-DDK flag (Figure 3A) or anti-GSTM1-5-specific antibodies (Figure 3B). The molecular weight of the overexpressed GSTMs was about 28–29 kDa, which is slightly greater than that of endogenous GSTMs (about 26 kDa). As shown in Figure 3A, the cell viability was significantly decreased in GSTM2, GSTM3 and GSTM5-overexpressed cells. Figure 3B indicates that anti-GSTM2 and -GSTM3 antibodies have a higher specificity than those against GSTM1, GSTM4 and GSTM5. Due to the nonspecific activity of the anti-GSTM5 antibody from GeneTex, another antibody from Abnova was used to generate the data presented in Figure 2B and Figure 4A. As the primary function of GSTs is to catalyze the conjugation of GSH to a wide variety of electrophilic substrates, the enzyme activity was also compared in 5637 cells overexpressing GSTM1-5, using CDNB as a substrate. The results suggested that GSTM1 possessed the greatest enzymatic activity (Figure 3C). Considering the differences in substrate binding affinity between GSTM1-5, the findings may not represent the real enzymatic activity of all cells overexpressing GSTMs; therefore, the cellular GSH level was also selected to assess the enzyme activity because the glutathione transferase consumes GSH as a result of this enzyme reaction. Figure 3D indicates that cellular GSH levels were decreased in cells overexpressing GSTM2 and GSTM5 but increased in GSTM3-overexpressed cells. Among them, GSTM5 overexpression depleted GSH levels to the greatest degree. The phenomenon of GSTM5 overexpression-reduced GSH cellular level was confirmed in two additional bladder cancer cell lines, RT4 and BFTC 905 (Figure 3E).

Figure 2. The status of GSTM5 DNA methylation in bladder cancer cells and clinical samples. (A) The effect of 10 µM 5-aza-dC on GSTM5 mRNA expression. (B) The effect of 10 µM 5-aza-dC on GSTM5 protein expression. The anti-GSTM5 antibodies were Abnova H00002949-D01P. (C) Correlation between age and GSTM5 DNA methylation level in 50 bladder cancer tissues and 50 normal human urine pellets. The linear regression formula is on the bottom right (R2 = 0.1074), which was calculated by Microsoft Excel. (D) GSTM5 DNA methylation level in 50 bladder cancer tissues and 50 normal human urine pellets. The statistical results were analyzed by SigmaPlot. (E) Kaplan–Meier plot showing the overall survival probability of 404 bladder cancer patients. (F) Kaplan–Meier plot of the relapse-free survival probability of 187 bladder cancer patients.

Figure 3. The expression and biological effects of GSTM1-5 by transient transfection expression. (A) The protein expression and cell viability after transfection. A total of 5637 cells were transfected with empty vectors or vectors with GSTM1-5 genes. After transfection for 24 h and 48 h, the proteins were detected by anti-DDK antibodies. Cell viability was analyzed after transfection for 32 h. (B) The protein expression and antibody characteristics. A total of 5637 cells were transfected with empty vectors or vectors with GSTM1-5 genes for 24 h; GSTM1~5 proteins were detected by their individual antibodies from GeneTex. (C) GST activity assay. A total of 5637 cells were transfected with empty vectors or vectors with GSTM1-5 genes for 24 h, the protein expression and GST activity were analyzed individually. (D) Cellular GSH level. A total of 5637 cells were transfected with empty vectors or vectors with GSTM1-5 genes for 24 h, the protein expression and GSH level (assayed by Cayman Chemical kit 703002) were analyzed. (E) Cellular GSH level in RT4 and BFTC 905 cells. After transient transfection for 24 h, cells were collected for GSH level detection (assayed by Cayman Chemical kit 703,002). All data are presented as the mean ± SE of three independent experiments. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

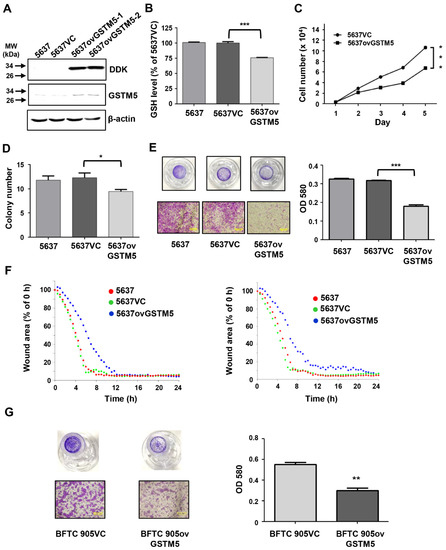

Figure 4. Bladder cancer cell proliferation and migration ability were decreased after GSTM5 overexpression. (A) The protein expression in 5637 cells with or without overexpression of empty vector (5637VC) or GSTM5 (5637ovGSTM5-1 and 5637ovGSTM5-2 were from 2 stably transfected colonies) was detected by Western blot. The anti-DDK antibodies (TA50011-100 from OriGene) and anti-GSTM5 antibodies (H00002949-D01P from Abnova) were used for detection. (B,C) GSTM5-overexpressed 5637 cells decreased intracellular GSH levels (B) and cell proliferation (C). The glutathione (GSH) levels were analyzed by a modified method described in Materials and Methods. (D) The number of colonies in cancer cells was decreased by GSTM5 overexpression. (E) The migration ability of 5637 cells was suppressed by GSTM5 overexpression by Transwell assay. Upper panel: Transwell insert with a circular membrane of 0.65 cm diameter. Lower panel: microscopic images: scale bar is 500 µm. All data are presented as the mean ± SE of three independent experiments. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. (F) Wound healing assay. Four different wound sites were recorded in each well for 24 h. The experiment was repeated once (right and left). Red line: 5637 cells, green line: 5637VC cells, blue line: 5637ovGSTM5 cells. (G) The migration capacity of BFTC 905 cells was inhibited by GSTM5 overexpression. Upper panel: Transwell inserts with a circular membrane of 0.65 cm diameter. Lower panel: microscopic images; scale bar is 500 µm.

4. GSTM5 Overexpression Decreases Intracellular GSH Levels and Suppresses the Proliferation and Migration of Bladder Cancer Cells

The conjugation of GSH with various electrophilic compounds is supposed to decrease the cellular damage caused by the reactive compounds. However, the process also depletes cellular GSH, which is integral to other protective mechanisms in addition to glutathione transferase, including the glutathione peroxidase pathway. Since GSTM5 decreased GSH levels to a greater degree than the other GSTMs (Figure 3D), the potential effect of this GSTM5-induced GSH reduction in cellular activity was investigated. After stable overexpression, the protein levels of GSTM5 were significantly increased in 5637 cells (5637ovGSTM5) (Figure 4A). The cellular GSH concentration was also decreased in 5637ovGSTM5 cells compared with those transfected with the vector control (5637VC) (Figure 4B).

The cell viability was significantly decreased after transient GSTM5 expression (Figure 3A). In the stable cell lines, the effects of GSTM5 on the proliferative rate and colony formation ability were analyzed. The results indicated that the cell proliferation and the number of colonies in soft agarose were decreased by GSTM5 overexpression (Figure 4C,D). Moreover, the migration activity of 5637ovGSTM5 cells was significantly lower than that of 5637VC cells by Transwell assay (Figure 4E). Wound healing assays also showed that GSTM5 overexpression retarded the healing rate (Figure 4F). GSTM5 overexpression inhibited cell migration was also observed in BFTC 905 cells (Figure 4G). The results of the aforementioned functional assays indicate that GSTM5 plays a suppressor role in both bladder cancer proliferation and migration.

5. Discussion

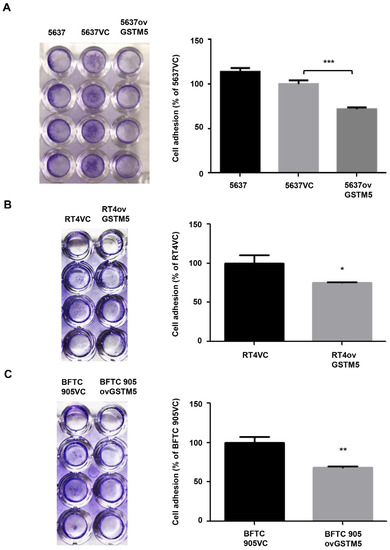

The present study revealed that low GSTM5 gene expression and high GSTM5 DNA methylation level tended to bladder cancer (Figure 1 and Figure 2D) and that patients with bladder cancer and high GSTM5 expression had a longer relapse-free survival (Figure 2F). In vitro assays demonstrated that GSTM5 inhibited cell proliferation (Figure 4C), colony formation (Figure 4D), cell migration (Figure 4E–G) and fibronectin adhesion (Figure 5). Furthermore, GSTM5-induced GSH decrease was found to play a role in the inhibition of cell proliferation and migration. GSH, a small molecule with a molecular weight of 307, is a cellular metabolite found in the majority of organisms. GSH is an antioxidant whose functions are dependent on the thiol group of cysteine residues, and in its reduced form, is a marketed drug for maintaining normal liver function. Furthermore, GSH also manifests other biologic functions, especially those associated with cancer cells. For example, increased GSH levels promoted cell proliferation in HepG2 cells [25] and cell metastasis in B16 melanoma cells [26]. The information elucidates that intracellular GSH concentration affects cancer cell function and plays a pivotal role in cancer characteristics.

Figure 5. Cell adhesion analysis. (A) The adhesion capacity of 5637, (B) RT4, and (C) BFTC 905 cells. Each VC cell was set as 100%. The data are presented as the mean ± SE of three independent experiments. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

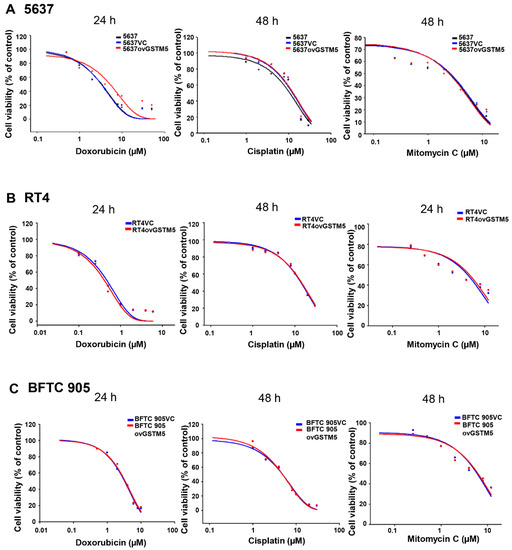

Redox homeostasis is important for both normal and cancer cells. The cells will undergo death following redox imbalance, where the levels of reactive oxygen species exceed the intrinsic antioxidant capacity. In cancer cells, elevated GSH level not only counteracts elevated oxidative stress but also contributes to chemotherapeutic resistance [27]. For example, GSH mediates Nrf2-induced boningmycin resistance in A549 and HepG2 cancer cells [28]. In the present study, the GSTM5-reduced GSH level inhibited the proliferation of bladder cancer cells (Figure 4C) but did not affect sensitivity to cisplatin and mitomycin C (Figure 6). Although the GSH conjugation function of GSTs can neutralize electrophilic endogenous and xenobiotic compounds by introducing a GSH molecule into them [29], GSTM5 overexpression accompanied by GSH decreasing did not affect the cytotoxic sensitivity of cisplatin and mitomycin C. This suggests that GSTM5 induction may be a potential strategy for bladder cancer treatment without inducing significant resistance to cisplatin and mitomycin C. GSTM5 overexpression slightly increased resistance to doxorubicin in 5637 cells (Figure 6A), increasing the IC50 from 3.2 µM (5637VC) to 5.2 µM (5637ovGSTM5). However, no change in doxorubicin sensitivity was observed in RT4 and BFTC 905 cells (Figure 6B,C). Therefore, the influence of GSTM5 on doxorubicin sensitivity is different between diverse cancer cells. It is still unclear what molecular mechanism contributes to the difference, but similar results have been reported in the study of GSTP1. In stable transfection of laryngeal carcinoma, HEp2 cells with human GSTP1 resulted in a 3-fold increase in doxorubicin resistance, compared with that of the control cells [30]. However, in ovarian cancer cells, stable GSTP1 knockdown did not significantly influence the IC50 value of doxorubicin [31]. According to the aforementioned reports and our results, it suggests that the influence of GSTs on drug sensitivity should be analyzed in individual cell lines.

Figure 6. GSTM5 overexpression does not significantly alter the sensitivity of cells to doxorubicin, cisplatin and mitomycin C. (A) The drug sensitivity of 5637, 5637VC and 5637ovGSTM5 cells (B) drug sensitivity of RT4VC and RT4ovGSTM5. (C) Drug sensitivity of BFTC 905VC and BFTC 905ovGSTM5. Cells were analyzed in a wide-range drug concentration by MTT assay. The individual drug treatment times are displayed above each data.

The anticancer role of GSTs has been reported in some studies. In non-small cell lung cancer, GSTM2 can inhibit cell migration [21]. In hepatocellular carcinoma cells, GSTZ1 also serves as a tumor suppressor [32]. To date, several studies have reported a correlation between GSTM5 and cancer, though the direct effects of GSTM5 on tumor cells remain unclear. For example, the gene expression of GSTM5 is lower in tumor tissues than in normal tissues in Barrett’s adenocarcinoma [23], GSTM5 expression is downregulated in breast and prostate cancer [33]. GSTM5 expression was also shown to be a positive biomarker for survival in ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma [34]. The aforementioned reports and the present study suggest that GSTM5 expression and its DNA methylation levels may act as biomarkers for bladder cancer progression. To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first to directly indicate that GSTM5 plays an anticancer role and that the GSTM5-reduced GSH mediates an important mechanism for this anticancer effect. However, it is still unknown how GSTM5 reduces GSH, which will be investigated in future metabolite analysis.

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 7–34.

- Antoni, S.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Znaor, A.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Bladder Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A Global Overview and Recent Trends. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 96–108.

- Stenehjem, D.D.; Tran, D.; Nkrumah, M.A.; Gupta, S. PD1/PDL1 inhibitors for the treatment of advanced urothelial bladder cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 5973–5989.

- Lower, G.M., Jr. Concepts in causality: Chemically induced human urinary bladder cancer. Cancer 1982, 49, 1056–1066.

- Brennan, P.; Bogillot, O.; Cordier, S.; Greiser, E.; Schill, W.; Vineis, P.; Lopez-Abente, G.; Tzonou, A.; Chang-Claude, J.; Bolm-Audorff, U.; et al. Cigarette smoking and bladder cancer in men: A pooled analysis of 11 case-control studies. Int. J. Cancer 2000, 86, 289–294.

- Straif, K.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Baan, R.; Grosse, Y.; Secretan, B.; El Ghissassi, F.; Bouvard, V.; Guha, N.; Freeman, C.; Galichet, L.; et al. A review of human carcinogens—Part C: Metals, arsenic, dusts, and fibres. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 453–454.

- Jou, Y.C.; Wang, S.C.; Dai, Y.C.; Chen, S.Y.; Shen, C.H.; Lee, Y.R.; Chen, L.C.; Liu, Y.W. Gene expression and DNA methylation regulation of arsenic in mouse bladder tissues and in human urothelial cells. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 42, 1005–1016.

- Burger, M.; Catto, J.W.; Dalbagni, G.; Grossman, H.B.; Herr, H.; Karakiewicz, P.; Kassouf, W.; Kiemeney, L.A.; La Vecchia, C.; Shariat, S.; et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of urothelial bladder cancer. Eur. Urol. 2013, 63, 234–241.

- Oakley, A. Glutathione transferases: A structural perspective. Drug Metab. Rev. 2011, 43, 138–151.

- Hayes, J.D.; Strange, R.C. Glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms and their biological consequences. Pharmacology 2000, 61, 154–166.

- Engel, L.S.; Taioli, E.; Pfeiffer, R.; Garcia-Closas, M.; Marcus, P.M.; Lan, Q.; Boffetta, P.; Vineis, P.; Autrup, H.; Bell, D.A.; et al. Pooled analysis and meta-analysis of glutathione S-transferase M1 and bladder cancer: A HuGE review. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 156, 95–109.

- Kang, H.W.; Song, P.H.; Ha, Y.S.; Kim, W.T.; Kim, Y.J.; Yun, S.J.; Lee, S.C.; Choi, Y.H.; Moon, S.K.; Kim, W.J. Glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 polymorphisms: Susceptibility and outcomes in muscle invasive bladder cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 3010–3019.

- Matic, M.; Pekmezovic, T.; Djukic, T.; Mimic-Oka, J.; Dragicevic, D.; Krivic, B.; Suvakov, S.; Savic-Radojevic, A.; Pljesa-Ercegovac, M.; Tulic, C.; et al. GSTA1, GSTM1, GSTP1, and GSTT1 polymorphisms and susceptibility to smoking-related bladder cancer: A case-control study. Urol. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1184–1192.

- Chuang, J.J.; Dai, Y.C.; Lin, Y.L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Lin, W.H.; Chan, H.L.; Liu, Y.W. Downregulation of glutathione S-transferase M1 protein in N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)nitrosamine-induced mouse bladder carcinogenesis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014, 279, 322–330.

- Pearson, W.R.; Vorachek, W.R.; Xu, S.J.; Berger, R.; Hart, I.; Vannais, D.; Patterson, D. Identification of class-mu glutathione transferase genes GSTM1-GSTM5 on human chromosome 1p13. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1993, 53, 220–233.

- Bhattacharjee, P.; Paul, S.; Banerjee, M.; Patra, D.; Banerjee, P.; Ghoshal, N.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Giri, A.K. Functional compensation of glutathione S-transferase M1 (GSTM1) null by another GST superfamily member, GSTM2. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2704.

- Yu, K.D.; Fan, L.; Di, G.H.; Yuan, W.T.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, W.; Chen, A.X.; Yang, C.; Wu, J.; Shen, Z.Z.; et al. Genetic variants in GSTM3 gene within GSTM4-GSTM2-GSTM1-GSTM5-GSTM3 cluster influence breast cancer susceptibility depending on GSTM1. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 121, 485–496.

- Weng, M.W.; Hsiao, Y.M.; Chiou, H.L.; Yang, S.F.; Hsieh, Y.S.; Cheng, Y.W.; Yang, C.H.; Ko, J.L. Alleviation of benzo[a]pyrene-diolepoxide-DNA damage in human lung carcinoma by glutathione S-transferase M2. DNA Repair 2005, 4, 493–502.

- Tang, S.C.; Sheu, G.T.; Wong, R.H.; Huang, C.Y.; Weng, M.W.; Lee, L.W.; Hsu, C.P.; Ko, J.L. Expression of glutathione S-transferase M2 in stage I/II non-small cell lung cancer and alleviation of DNA damage exposure to benzo[a]pyrene. Toxicol. Lett. 2010, 192, 316–323.

- Tang, S.C.; Wu, M.F.; Wong, R.H.; Liu, Y.F.; Tang, L.C.; Lai, C.H.; Hsu, C.P.; Ko, J.L. Epigenetic mechanisms for silencing glutathione S-transferase m2 expression by hypermethylated specificity protein 1 binding in lung cancer. Cancer 2011, 117, 3209–3221.

- Tang, S.C.; Wu, C.H.; Lai, C.H.; Sung, W.W.; Yang, W.J.; Tang, L.C.; Hsu, C.P.; Ko, J.L. Glutathione S-transferase mu2 suppresses cancer cell metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. MCR 2013, 11, 518–529.

- Ibragimova, I.; Dulaimi, E.; Slifker, M.J.; Chen, D.Y.; Uzzo, R.G.; Cairns, P. A global profile of gene promoter methylation in treatment-naive urothelial cancer. Epigenetics 2014, 9, 760–773.

- Peng, D.F.; Razvi, M.; Chen, H.; Washington, K.; Roessner, A.; Schneider-Stock, R.; El-Rifai, W. DNA hypermethylation regulates the expression of members of the Mu-class glutathione S-transferases and glutathione peroxidases in Barrett’s adenocarcinoma. Gut 2009, 58, 5–15.

- Wang, S.C.; Huang, C.C.; Shen, C.H.; Lin, L.C.; Zhao, P.W.; Chen, S.Y.; Deng, Y.C.; Liu, Y.W. Gene Expression and DNA Methylation Status of Glutathione S-Transferase Mu1 and Mu5 in Urothelial Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159102.

- Huang, Z.Z.; Chen, C.; Zeng, Z.; Yang, H.; Oh, J.; Chen, L.; Lu, S.C. Mechanism and significance of increased glutathione level in human hepatocellular carcinoma and liver regeneration. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 19–21.

- Carretero, J.; Obrador, E.; Anasagasti, M.J.; Martin, J.J.; Vidal-Vanaclocha, F.; Estrela, J.M. Growth-associated changes in glutathione content correlate with liver metastatic activity of B16 melanoma cells. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 1999, 17, 567–574.

- Traverso, N.; Ricciarelli, R.; Nitti, M.; Marengo, B.; Furfaro, A.L.; Pronzato, M.A.; Marinari, U.M.; Domenicotti, C. Role of glutathione in cancer progression and chemoresistance. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2013, 2013, 972913.

- Zhang, H.X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, R.; He, Q.Y. Nrf2 mediates the resistance of human A549 and HepG2 cancer cells to boningmycin, a new antitumor antibiotic, in vitro through regulation of glutathione levels. Acta Pharm. Sin. 2018, 39, 1661–1669.

- Hayes, J.D.; Flanagan, J.U.; Jowsey, I.R. Glutathione transferases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005, 45, 51–88.

- Harbottle, A.; Daly, A.K.; Atherton, K.; Campbell, F.C. Role of glutathione S-transferase P1, P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 in acquired doxorubicin resistance. Int J. Cancer 2001, 92, 777–783.

- Sawers, L.; Ferguson, M.J.; Ihrig, B.R.; Young, H.C.; Chakravarty, P.; Wolf, C.R.; Smith, G. Glutathione S-transferase P1 (GSTP1) directly influences platinum drug chemosensitivity in ovarian tumour cell lines. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 111, 1150–1158.

- Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Lei, C.; Yang, F.; Liang, L.; Chen, C.; Xia, J.; Wang, K.; Tang, N. GSTZ1 deficiency promotes hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation via activation of the KEAP1/NRF2 pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 438.

- Sun, C.; Gu, Y.; Chen, G.; Du, Y. Bioinformatics Analysis of Stromal Molecular Signatures Associated with Breast and Prostate Cancer. J. Comput. Biol. 2019, 26, 1130–1139.

- Wang, Y.; Lei, L.; Chi, Y.G.; Liu, L.B.; Yang, B.P. A comprehensive understanding of ovarian carcinoma survival prognosis by novel biomarkers. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 23, 8257–8264.