| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Philipp Ernst | + 2055 word(s) | 2055 | 2021-03-15 12:21:41 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 2055 | 2021-03-25 11:18:39 | | |

Video Upload Options

Senescence is a cellular state that is involved in aging-associated diseases but may also prohibit the development of pre-cancerous lesions and tumor growth. Senescent cells are actively secreting chemo- and cytokines, and this senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) can contribute to both early anti-tumorigenic and long-term pro-tumorigenic effects.

1. Introduction on Cellular Senescence

The inability of somatic mammalian cells to undergo further replication was first described as cellular senescence in 1961 [1]. This physiologically limited replicative capacity, known as the “Hayflick limit”, results from successive shortening of telomeres during each cell division [2][3]. Telomerase, a ribonucleoprotein enzyme complex that counteracts telomere shortening, is transcriptionally silent in normal human somatic cells, except in certain stem cells, including hematopoietic stem cells, but can be reactivated in neoplastic cells [2][4][5]. Senescent cells are unable to replicate because of halted DNA synthesis due to an arrested cell cycle in the G1/S interphase [6][7]. In addition, these cells are not able to respond to physiological mitogenic stimuli, although the number of receptors on the surface remains unchanged [8]. In contrast to senescent cells, quiescent or pre-senescent cells are nonreplicating, diploid cells in the G0 phase that are able to restore proliferation after suitable stimuli. The only senescent cells that can re-enter the cell cycle under certain conditions are senescent tumor cells [9]. In addition, replicative senescence state cells can develop so-called premature senescence independent of their biologic or in vitro culture age. This state can be induced by oncogenes, including Ras and factors that cause DNA damage, such as oxidative stress, alcohol, and bacterial lipopolysaccharides [10][11][12][13]. Increased expression of anti-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) protein and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors p16INK4a and p21WAF1, as well as reduced proapoptotic caspase activity, are considered typical features of senescent cells [14][15][16][17][18]. Furthermore, the formation of a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) is characteristic, which among growth factors, proteases, and other factors is mainly characterized by the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. In addition to autocrine senescence maintenance, these factors can exert opposing effects on the surrounding microenvironment with both senescence-inducing and mitogenic stimulation [19][20].

2. Molecular Mechanisms of Senescence

2.1. DNA Damage Response (DDR)

DNA damage response (DDR) is an important mechanism for the initiation of the senescence pathway. In the context of replicative senescence, progressive shortening of telomeres leads to telomere uncapping, which is sensed as double-stranded DNA breaks and thereby activates DDR [21]. On the other hand, DDR can be caused by oncogene-induced DNA replication stress, leading to telomere dysfunction, which seems to be a critical tumor-suppressive mechanism [22]. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and ATM-Rad3 related (ATR) are phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3K) and important components in repairing DNA damage and maintaining telomere length [23]. ATM and ATR bind to damaged DNA sites and phosphorylate histone H2AX. While ATM is primarily activated by double-stranded DNA breaks (DSB), ATR binds in association with ATR-interacting protein (ATRIP) to Replication protein A (RPA)-labeled single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) created by replication arrests [24][25]. By local changes in chromatin structure, γH2AX leads to recruiting the DNA repair complex with a focal assembly of the checkpoint kinases CHK1 and CHK2, which can then be phosphorylated by ATR and ATM. Both ATM and phosphorylated CHK2 at Threonine 68 are able to activate p53 by phosphorylation, which leads to the induction of cell cycle arrest [26]. While the ATM-CHK2 axis plays an auxiliary role, especially in response to DSB, the ATR-CHK1 axis is the main effector of DNA damage and replication control points [27].

2.2. Senescence Associated Molecular Pathways Are Interconnected

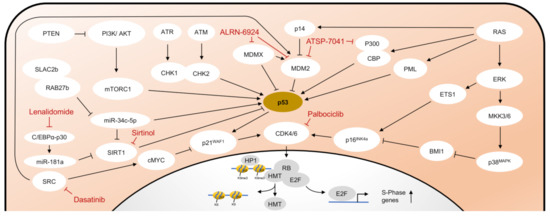

Depending on the trigger, different pathways are activated to induce senescence. As already described, p53 is activated by a variety of triggers, such as DDR, critical telomere shortening, or activation of oncogenic signaling pathways (e.g., RAS-signaling). The activity of p53 is mainly controlled by the E3-ubiquitin ligase Mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2). The transcription of MDM2 is, in turn, induced by p53 as a negative feedback loop since MDM2 acts as a negative regulator of p53 by direct binding and degradation via the ubiquitin–proteasome complex [28][29]. MDMX (also known as MDM4), another endogenous inhibitor of p53, promotes MDM2 activation and inhibits p53 transactivation [30]. When activated in response to oncogenic RAS, the intranuclear protein p14 binds MDM2 in the nucleus and thereby prevents the degradation of p53 [31][32]. Likewise, in response to DSB, MDM2 is inhibited by phosphorylation through activated ATM [33]. Independent of DDR, the translation of p53 is enhanced by AKT by inducing the mammalian target of the rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) [31]. The PI3K/AKT pathway is in turn negatively regulated by the phosphatase PTEN [31][34]. The activity of p53 is also influenced by post-translational modifications. In response to oncogenic RAS, promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) activates p53 through acetylation [35]. Similarly, coactivators p300 and CREB-binding protein (CBP) also lead to acetylation of p53 through stress stimuli, such as UV radiation, hypoxia, and alkylating agents [16]. The activity of p300 and CBP is in turn suppressed by MDM2 [36]. Silent information regulator two ortholog 1 (SIRT1) belongs to the family of sirtuins, a group of highly conserved proteins with NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase activity. By deacetylation of p53, SIRT1 counteracts PML-mediated senescence [37]. SIRT1 is, in turn, a target gene of miR-34c-5p and miR-181a, which inhibit its expression and thus reduce deacetylation of p53 [38][39][40]. The immediately activated target gene after activation of p53 is the p21WAF1 gene, which encodes the cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) inhibitor p21WAF1. The inhibition of CDK2 by p21WAF1 leads to decreased phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein (RB).

In contrast to DDR and telomere dependent mechanisms, the ERK-p38MAPK pathway is activated independently of the telomere function but typically in the presence of oxidative stress or oncogenic signaling. Oncogenic RAS induces premature senescence by sequential activation of MEK-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). Accumulated MAP kinase kinases, MKK3 and MKK6, activate p38MAPK that thereby is able to degrade BMI1, a member of the Polycomb group gene family and transcriptional repressor of p16INK4a [41]. In addition, the MAPK/ERK cascade stimulates the activity of ETS1, which causes an increased transcription of p16INK4a [42]. Upregulated p16INK4a forms complexes with the RB kinases CDK4 and CDK6, which leads to long-term inhibition and stabilization of the hypo-phosphorylated state of RB.

As previously discussed, the final link of both pathways is formed by RB (Figure 1). RB is a key regulator to initiate senescence, as its phosphorylation state can determine the progression of cells from the G1 to S phase of the cell cycle. In contrast, hypophosphorylated RB forms a complex with the transcription factor E2F. In addition to suppression of E2F activity, the RB/E2F complex leads to the recruitment of histone methyltransferases, which results in focal heterochromatin formation of E2F target gene promoters through transcriptional repressive trimethylation of H3K9 [43]. As a result, S-phase-promoting genes remain stably suppressed and cells remain in growth arrest in the late G1 phase.

Figure 1. Pathways in cellular senescence. Schematic representation of the major pathways of cellular senescence and selected compounds for senescence induction or senolysis. HMT, Histone methyltransferase. Other abbreviations are explained in the text in detail.

2.3. The Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP)

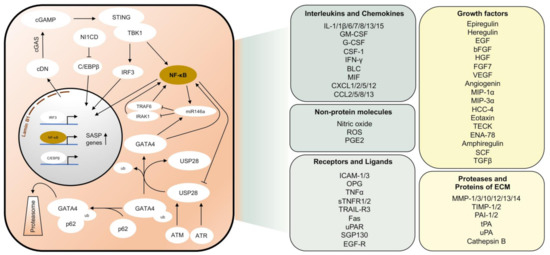

Senescent cells are usually able to express a set of molecules that define a so-called ‘Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype’ (SASP). These factors include a variety of chemokines, pro-inflammatory cytokines, proteases, growth factors, and non-protein molecules (Figure 2). The phenotype of SASP may vary since transcriptional regulation of SASP-associated molecules is highly heterogeneous among different cell types [44]. Different mechanisms have been described that are responsible for initiating the expression of SASP factors. In the context of DDR, the accumulation of cytoplasmic chromatin fragments has been described that are released from the nuclei of primary senescent cells [45]. The release of genomic DNA from the nucleus into the cytoplasm of senescent cells is caused by autophagic degradation of lamin B1, the major structural component of the nuclear membrane [46]. Cyclic guanosine monophosphate (GMP)-adenosine monophosphate (AMP) synthase (cGAS) is a cytosolic DNA sensor that recognizes cytoplasmatic DNA in the form of cyclic dinucleotides found during pathogenic infections [47]. Cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP), which is synthesized by cGAS, in turn, activates the 379 amino acid protein stimulator of interferon genes (STING) located in the endoplasmic reticulum [48][49]. Activated STING forms a complex with TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and shifts to perinuclear regions, where TBK1, released to endolysosomal compartments, is able to phosphorylate the transcription factors interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and nuclear factor ‘kappa-light-chain-enhancer’ of activated B-cells (NF-κB) and thereby enables translocation to the nucleus [50][51].

Figure 2. Pathways responsible for the induction of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Schematic representation of major pathways that are activated in senescent cells leading to the expression of SASP genes (left panel). Most important SASP factors according to [52][53][54] (right panel). cDN, cyclic dinucleotides. ECM, Extracellular matrix. ub, Ubiquitin.

Another activator of the SASP is the transcription factor GATA4 [55]. Under normal conditions, GATA4 is degraded through the autophagic adaptor protein p62 by selective autophagy. The mechanism by which GATA4 is recognized by p62 remains elusive so far. However, p62 can bind ubiquitinated proteins with its UBA domain [56]. In response to DNA damage, phosphorylation of the deubiquitinase USP28 by DDR kinases, ATM, and ATR leads to deubiquitination of either GATA4 or its associated factor [57]. Thus, GATA4 is stabilized and able to activate the SASP via NF-κB activation [55]. At the same time, overactivation of SASP is also prohibited. MiR-146a inhibits the expression of TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) and IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) and, therefore, acts as a negative regulator of NF-κB [58]. In addition to NF-κB, which upregulates miR-146a expression as a negative feedback mechanism during inflammatory stimuli [59], expression of miR-146a is also stimulated by GATA4 [55].

Regulation of SASP has also been linked to JAK2/STAT3 signaling [60]. This pathway is activated in a specific subtype of p53-mediated senescence, initiated by an acute inactivation of PTEN [61]. In pancreatic tumor cells with loss of PTEN-induced senescence, the mainly immunosuppressive SASP could be reprogrammed by inhibiting the JAK2/STAT3 pathway, thus enabling tumor clearance by immunostimulatory cytokines [60]. P53 is required for the growth arrest in senescent cells but not for the induction of the SASP [62]. However, cells with non-functional p53 secrete significantly higher levels of most SASP factors. P53, therefore, restrains the SASP by negative feedback mechanisms to reduce the development of a pro-inflammatory tissue environment. One feedback loop is the negative regulation of USP28 by p53, thereby contributing to the attenuation of the SASP [57]. Other mechanisms include the restriction of p38MAPK activation, a stress-inducible kinase that acts as a DDR-independent regulator of the SASP [63].

Importantly, NF-κB signaling represents a bottleneck in the development of the SASP. In addition to described upstream kinase cascades, the activation of the NF-κB system is usually connected with several pattern recognition receptor pathways, e.g., toll-like receptors (TLR) and inflammasomes [64]. The transcriptional capacity of the NF-kB factors can be regulated by various kinases, of which inhibitory κB (IκB) kinases (IKK) α/β and NF-κB inducing kinase (NIK) are the most important. The NF-κB transcription factors RelA/p65, c-Rel, RelB, p50/p105, and p52/p100 are located in the cytoplasm in a dimerized state and inhibited by binding to the IκB proteins IκBα, IκBβ, IκBγ, IκBδ, IκBε, IκBζ, and Bcl3 [65]. After IκB proteins have been phosphorylated by activating kinases, they are released from the complex to be degraded by proteasomes. The NF-κB transcription factors are then able to translocate into the nucleus and transactivate the expression of certain target genes that define the SASP [65].

Another pro-inflammatory transcription factor, to which most SASP regulators converge, is CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ). In collaboration with NF-κB, C/EBPβ regulates many SASP components and inflammatory cytokines [19][55][66]. During premature senescence, there is transient upregulation of NOTCH homolog 1 intracellular domain (N1ICD), which inhibits C/EBPβ. Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) is upregulated together with N1ICD and leads to the expression of an immunosuppressive secretory phenotype. A decrease in N1ICD over time disinhibits C/EBPβ, which together with NF-κB stimulates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL1a, IL6, and IL8) [66]. IL-6, a pleiotropic cytokine and SASP factor, acts mitogenic on neighboring cells on the one hand and is required cell-autonomously, on the other hand, to reinforce senescence by activating the promotor of CDKN2B encoding p15INK4b that promote p16INK4a by suppressing CDK4 and CDK6 [19].

References

- Hayflick, L.; Moorhead, P.S. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res. 1961, 25, 585–621.

- Harley, C.B.; Futcher, A.B.; Greider, C.W. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature 1990, 345, 458–460.

- Olovnikov, A.M. A theory of marginotomy. The incomplete copying of template margin in enzymic synthesis of polynucleotides and biological significance of the phenomenon. J. Theor. Biol. 1973, 41, 181–190.

- Kim, N.W.; Piatyszek, M.A.; Prowse, K.R.; Harley, C.B.; West, M.D.; Ho, P.L.; Coviello, G.M.; Wright, W.E.; Weinrich, S.L.; Shay, J.W. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science 1994, 266, 2011–2015.

- Chiu, C.P.; Dragowska, W.; Kim, N.W.; Vaziri, H.; Yui, J.; Thomas, T.E.; Harley, C.B.; Lansdorp, P.M. Differential expression of telomerase activity in hematopoietic progenitors from adult human bone marrow. Stem. Cells 1996, 14, 239–248.

- Afshari, C.A.; Vojta, P.J.; Annab, L.A.; Futreal, P.A.; Willard, T.B.; Barrett, J.C. Investigation of the role of G1/S cell cycle mediators in cellular senescence. Exp. Cell Res. 1993, 209, 231–237.

- Sherwood, S.W.; Rush, D.; Ellsworth, J.L.; Schimke, R.T. Defining cellular senescence in IMR-90 cells: A flow cytometric analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 9086–9090.

- Hensler, P.J.; Pereira-Smith, O.M. Human replicative senescence. A molecular study. Am. J. Pathol. 1995, 147, 1–8.

- Saleh, T.; Tyutyunyk-Massey, L.; Gewirtz, D.A. Tumor Cell Escape from Therapy-Induced Senescence as a Model of Disease Recurrence after Dormancy. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 1044–1046.

- Tu, Z.; Aird, K.M.; Bitler, B.G.; Nicodemus, J.P.; Beeharry, N.; Xia, B.; Yen, T.J.; Zhang, R. Oncogenic RAS regulates BRIP1 expression to induce dissociation of BRCA1 from chromatin, inhibit DNA repair, and promote senescence. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 1077–1091.

- Chen, X.; Li, M.; Yan, J.; Liu, T.; Pan, G.; Yang, H.; Pei, M.; He, F. Alcohol Induces Cellular Senescence and Impairs Osteogenic Potential in Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Alcohol. Alcohol. 2017, 52, 289–297.

- Kim, C.O.; Huh, A.J.; Han, S.H.; Kim, J.M. Analysis of cellular senescence induced by lipopolysaccharide in pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2012, 54, e35–e41.

- Serrano, M.; Lin, A.W.; McCurrach, M.E.; Beach, D.; Lowe, S.W. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell 1997, 88, 593–602.

- Serrano, M.; Hannon, G.J.; Beach, D. A new regulatory motif in cell-cycle control causing specific inhibition of cyclin D/CDK4. Nature 1993, 366, 704–707.

- Noda, A.; Ning, Y.; Venable, S.F.; Pereira-Smith, O.M.; Smith, J.R. Cloning of senescent cell-derived inhibitors of DNA synthesis using an expression screen. Exp. Cell Res. 1994, 211, 90–98.

- Muller, M. Cellular senescence: Molecular mechanisms, in vivo significance, and redox considerations. Antioxid. Redox. Signal 2009, 11, 59–98.

- Wang, E. Senescent human fibroblasts resist programmed cell death, and failure to suppress bcl2 is involved. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 2284–2292.

- Ohshima, S. Apoptosis in stress-induced and spontaneously senescent human fibroblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 324, 241–246.

- Kuilman, T.; Michaloglou, C.; Vredeveld, L.C.; Douma, S.; Van Doorn, R.; Desmet, C.J.; Aarden, L.A.; Mooi, W.J.; Peeper, D.S. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell 2008, 133, 1019–1031.

- Kuilman, T.; Michaloglou, C.; Mooi, W.J.; Peeper, D.S. The essence of senescence. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 2463–2479.

- Stewart, S.A.; Ben-Porath, I.; Carey, V.J.; O’Connor, B.F.; Hahn, W.C.; Weinberg, R.A. Erosion of the telomeric single-strand overhang at replicative senescence. Nat. Genet. 2003, 33, 492–496.

- Suram, A.; Kaplunov, J.; Patel, P.L.; Ruan, H.; Cerutti, A.; Boccardi, V.; Fumagalli, M.; Di Micco, R.; Mirani, N.; Gurung, R.L.; et al. Oncogene-induced telomere dysfunction enforces cellular senescence in human cancer precursor lesions. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 2839–2851.

- Shiloh, Y. ATM and related protein kinases: Safeguarding genome integrity. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 155–168.

- Lee, J.H.; Paull, T.T. Activation and regulation of ATM kinase activity in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Oncogene 2007, 26, 7741–7748.

- Zou, L.; Elledge, S.J. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science 2003, 300, 1542–1548.

- Smith, J.; Tho, L.M.; Xu, N.; Gillespie, D.A. The ATM-Chk2 and ATR-Chk1 pathways in DNA damage signaling and cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2010, 108, 73–112.

- Kastan, M.B.; Bartek, J. Cell-cycle checkpoints and cancer. Nature 2004, 432, 316–323.

- Roth, J.; Dobbelstein, M.; Freedman, D.A.; Shenk, T.; Levine, A.J. Nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of the hdm2 oncoprotein regulates the levels of the p53 protein via a pathway used by the human immunodeficiency virus rev protein. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 554–564.

- Kubbutat, M.H.; Jones, S.N.; Vousden, K.H. Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature 1997, 387, 299–303.

- Shvarts, A.; Steegenga, W.T.; Riteco, N.; Van Laar, T.; Dekker, P.; Bazuine, M.; Van Ham, R.C.; Van der Houven van Oordt, W.; Hateboer, G.; Van der Eb, A.J.; et al. MDMX: A novel p53-binding protein with some functional properties of MDM2. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 5349–5357.

- Astle, M.V.; Hannan, K.M.; Ng, P.Y.; Lee, R.S.; George, A.J.; Hsu, A.K.; Haupt, Y.; Hannan, R.D.; Pearson, R.B. AKT induces senescence in human cells via mTORC1 and p53 in the absence of DNA damage: Implications for targeting mTOR during malignancy. Oncogene 2012, 31, 1949–1962.

- Liu, P.; Lu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Shang, D.; Zhao, Z.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, F.; Liu, H.; Tu, Z. Cellular Senescence-Inducing Small Molecules for Cancer Treatment. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2019, 19, 109–119.

- Lavin, M.F.; Kozlov, S. ATM activation and DNA damage response. Cell Cycle 2007, 6, 931–942.

- Chu, E.C.; Tarnawski, A.S. PTEN regulatory functions in tumor suppression and cell biology. Med. Sci. Monit. 2004, 10, RA235–RA241.

- Pearson, M.; Carbone, R.; Sebastiani, C.; Cioce, M.; Fagioli, M.; Saito, S.; Higashimoto, Y.; Appella, E.; Minucci, S.; Pandolfi, P.P.; et al. PML regulates p53 acetylation and premature senescence induced by oncogenic Ras. Nature 2000, 406, 207–210.

- Ito, A.; Lai, C.H.; Zhao, X.; Saito, S.; Hamilton, M.H.; Appella, E.; Yao, T.P. p300/CBP-mediated p53 acetylation is commonly induced by p53-activating agents and inhibited by MDM2. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 1331–1340.

- Langley, E.; Pearson, M.; Faretta, M.; Bauer, U.M.; Frye, R.A.; Minucci, S.; Pelicci, P.G.; Kouzarides, T. Human SIR2 deacetylates p53 and antagonizes PML/p53-induced cellular senescence. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 2383–2396.

- Peng, D.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Ma, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, H.; Luo, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, L. miR-34c-5p promotes eradication of acute myeloid leukemia stem cells by inducing senescence through selective RAB27B targeting to inhibit exosome shedding. Leukemia 2018, 32, 1180–1188.

- Zhou, B.; Li, C.; Qi, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wu, J.X.; Hu, Y.N.; Wu, D.M.; Liu, Y.; Yan, T.T.; et al. Downregulation of miR-181a upregulates sirtuin-1 (SIRT1) and improves hepatic insulin sensitivity. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 2032–2043.

- Zhou, D.; Xu, P.; Zhou, X.; Diao, Z.; Ouyang, J.; Yan, G.; Chen, B. MiR-181a enhances drug sensitivity of mixed lineage leukemia-rearranged acute myeloid leukemia by increasing poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase1 acetylation. Leuk. Lymphoma 2020, 1–11.

- Kim, J.; Hwangbo, J.; Wong, P.K. p38 MAPK-Mediated Bmi-1 down-regulation and defective proliferation in ATM-deficient neural stem cells can be restored by Akt activation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16615.

- Rayess, H.; Wang, M.B.; Srivatsan, E.S. Cellular senescence and tumor suppressor gene p16. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 1715–1725.

- Narita, M.; Nunez, S.; Heard, E.; Narita, M.; Lin, A.W.; Hearn, S.A.; Spector, D.L.; Hannon, G.J.; Lowe, S.W. Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell 2003, 113, 703–716.

- Hernandez-Segura, A.; De Jong, T.V.; Melov, S.; Guryev, V.; Campisi, J.; Demaria, M. Unmasking Transcriptional Heterogeneity in Senescent Cells. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 2652–2660.e2654.

- Dou, Z.; Ghosh, K.; Vizioli, M.G.; Zhu, J.; Sen, P.; Wangensteen, K.J.; Simithy, J.; Lan, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Cytoplasmic chromatin triggers inflammation in senescence and cancer. Nature 2017, 550, 402–406.

- Shimi, T.; Butin-Israeli, V.; Adam, S.A.; Hamanaka, R.B.; Goldman, A.E.; Lucas, C.A.; Shumaker, D.K.; Kosak, S.T.; Chandel, N.S.; Goldman, R.D. The role of nuclear lamin B1 in cell proliferation and senescence. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 2579–2593.

- Sun, L.; Wu, J.; Du, F.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.J. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science 2013, 339, 786–791.

- Cai, X.; Chiu, Y.H.; Chen, Z.J. The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing and signaling. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 289–296.

- Ablasser, A.; Goldeck, M.; Cavlar, T.; Deimling, T.; Witte, G.; Rohl, I.; Hopfner, K.P.; Ludwig, J.; Hornung, V. cGAS produces a 2′-5′-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nature 2013, 498, 380–384.

- Ishikawa, H.; Ma, Z.; Barber, G.N. STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferon-dependent innate immunity. Nature 2009, 461, 788–792.

- Barber, G.N. STING: Infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 760–770.

- Mabrouk, N.; Ghione, S.; Laurens, V.; Plenchette, S.; Bettaieb, A.; Paul, C. Senescence and Cancer: Role of Nitric Oxide (NO) in SASP. Cancers 2020, 12, 1145.

- Coppe, J.P.; Desprez, P.Y.; Krtolica, A.; Campisi, J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: The dark side of tumor suppression. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2010, 5, 99–118.

- Calcinotto, A.; Kohli, J.; Zagato, E.; Pellegrini, L.; Demaria, M.; Alimonti, A. Cellular Senescence: Aging, Cancer, and Injury. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1047–1078.

- Kang, C.; Xu, Q.; Martin, T.D.; Li, M.Z.; Demaria, M.; Aron, L.; Lu, T.; Yankner, B.A.; Campisi, J.; Elledge, S.J. The DNA damage response induces inflammation and senescence by inhibiting autophagy of GATA4. Science 2015, 349, aaa5612.

- Long, J.; Gallagher, T.R.; Cavey, J.R.; Sheppard, P.W.; Ralston, S.H.; Layfield, R.; Searle, M.S. Ubiquitin recognition by the ubiquitin-associated domain of p62 involves a novel conformational switch. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 5427–5440.

- Mazzucco, A.E.; Smogorzewska, A.; Kang, C.; Luo, J.; Schlabach, M.R.; Xu, Q.; Patel, R.; Elledge, S.J. Genetic interrogation of replicative senescence uncovers a dual role for USP28 in coordinating the p53 and GATA4 branches of the senescence program. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 1933–1938.

- Boldin, M.P.; Taganov, K.D.; Rao, D.S.; Yang, L.; Zhao, J.L.; Kalwani, M.; Garcia-Flores, Y.; Luong, M.; Devrekanli, A.; Xu, J.; et al. miR-146a is a significant brake on autoimmunity, myeloproliferation, and cancer in mice. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 1189–1201.

- Taganov, K.D.; Boldin, M.P.; Chang, K.J.; Baltimore, D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 12481–12486.

- Toso, A.; Revandkar, A.; Di Mitri, D.; Guccini, I.; Proietti, M.; Sarti, M.; Pinton, S.; Zhang, J.; Kalathur, M.; Civenni, G.; et al. Enhancing chemotherapy efficacy in Pten-deficient prostate tumors by activating the senescence-associated antitumor immunity. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 75–89.

- Chen, Z.; Trotman, L.C.; Shaffer, D.; Lin, H.K.; Dotan, Z.A.; Niki, M.; Koutcher, J.A.; Scher, H.I.; Ludwig, T.; Gerald, W.; et al. Crucial role of p53-dependent cellular senescence in suppression of Pten-deficient tumorigenesis. Nature 2005, 436, 725–730.

- Coppe, J.P.; Patil, C.K.; Rodier, F.; Sun, Y.; Munoz, D.P.; Goldstein, J.; Nelson, P.S.; Desprez, P.Y.; Campisi, J. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, 2853–2868.

- Freund, A.; Patil, C.K.; Campisi, J. p38MAPK is a novel DNA damage response-independent regulator of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 1536–1548.

- Oeckinghaus, A.; Hayden, M.S.; Ghosh, S. Crosstalk in NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 695–708.

- Salminen, A.; Kauppinen, A.; Kaarniranta, K. Emerging role of NF-kappaB signaling in the induction of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Cell Signal 2012, 24, 835–845.

- Ito, Y.; Hoare, M.; Narita, M. Spatial and Temporal Control of Senescence. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 820–832.