| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jiao Jiao Li | + 2646 word(s) | 2646 | 2021-03-24 09:11:46 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 2646 | 2021-03-25 10:28:43 | | |

Video Upload Options

Over the past two decades, mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) have demonstrated great potential in the treatment of inflammation-related conditions. Recently, the use of MSC-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) for treating inflammation-related conditions has shown therapeutic potential in a range of preclinical studies. This topic explores the current research landscape pertaining to the use of MSC-derived EVs as anti-inflammatory and pro-regenerative agents in a range of inflammation-related conditions: osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, cardiovascular disease, and preeclampsia. Along with this, the mechanisms by which MSC-derived EVs exert their beneficial effects on the damaged or degenerative tissues are discussed, together with current challenges and future perspectives.

1. Introduction

Inflammation is a crucial mechanism initiated by the body as a first line of defence against harmful stimuli such as pathogens, tissue damage, radiation, and toxic compounds [1]. An acute inflammatory response is normally triggered by immune cells sensing a pathogen or endogenous stress signal, resulting in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. This reaction can have a multitude of effects, including neutrophil and macrophage activation, vasodilation, hypotension, induction of capillary leakage, and platelet activation [1][2]. These effects typically facilitate tissue regeneration or the clearance of infection, ultimately leading to the removal of the initial harmful stimuli. Once cleared of harmful stimuli, the multifaceted process of inflammation resolution can begin, which involves substantial reprogramming of cells to the anti-inflammatory phenotype [2]. Unfortunately, acute inflammation can often progress into chronic non-resolving inflammation, which may elicit more harm to the body than the initial stimuli that triggered the inflammatory response [3]. Though not the primary cause, non-resolving chronic inflammation has been identified to play an important role in the pathogenesis of a myriad of debilitating diseases including rheumatoid arthritis [2][4], atherosclerosis [2][5], Alzheimer’s disease [6], various cancers [2][7][8][9], asthma [10], type 2 diabetes [11], diabetic nephropathy [12], osteoarthritis [13][14][15], multiple sclerosis [16], depression [17], chronic rhinosinusitis [18], idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [19], and atrial fibrillation [20]. These diseases share many common pathophysiological mechanisms, including the activation of inflammatory cells, release of soluble inflammatory factors (most notably cytokines and chemokines), and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodelling [21].

With such a long list of conditions in which non-resolving inflammation plays a key role, there is no doubt that it imposes an immense burden on society. Unfortunately, commonly used anti-inflammatory treatments such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and glucocorticoids appear to merely relieve symptoms of the underlying disease, and there is little evidence to demonstrate that these treatments have any effectiveness in ceasing disease progression [22]. As such, there is an urgent need to develop new therapeutic strategies, which perhaps can act on multiple pathways of disease progression rather than only targeting the inflammatory characteristics.

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), previously commonly referred to as mesenchymal stem cells [23], are the most widely explored cell type for cell-based therapeutics, and their use in clinical trials to treat a wide range of diseases has increased dramatically over the past two decades [24]. The literature provides ample evidence of studies showing the beneficial effects of MSCs when applied for treating inflammatory diseases in animal models [25][26], with evidence in multiple tissue types including cardiovascular (myocardial infarction, vascular disease, peripheral artery disease, preeclampsia); neural (multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease); and osteochondral (rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis) [26][27][28][29]. As such, there is an ongoing urge within the scientific community to translate these promising findings to humans. It was initially believed that the therapeutic potential of MSCs was a function of injected MSCs engrafting to existing cellular structures, and subsequently differentiating and facilitating the formation of neo-tissue [30]. However, this belief has been subverted in recent years. It has been widely observed that implanted MSCs show very low levels of engraftment (less than 3%) in the target tissue [31], with the vast majority of the population of implanted cells being rapidly cleared [32]. For this reason, other mechanisms have been investigated, and it is now evident that the regenerative, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory capacity of MSCs is exerted through their secretion of paracrine factors [33][34][35].

The MSC secretome accounts for all molecules secreted by the cell. It includes a variety of chemokines, cytokines, immunomodulatory factors, and ECM components, along with a range of other proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids [32]. It is suggested that once MSCs are implanted into damaged or diseased tissue, they secrete a host of anti-inflammatory and regenerative factors that elicit a therapeutic response. Importantly, the secretion profile appears to be a function of the microenvironment around the secreting cell, for instance, MSCs exposed to inflammatory signals can elicit an enhanced secretory profile [36]. However, the majority of investigations surrounding this observation have been in vitro gene expression or proteomic studies and require further in vivo validation [32].

It has been suggested that the apoptosis or phagocytosis of implanted MSCs act as the trigger for the observed immunomodulatory effects elicited by MSCs [32]. There are so far two key observations supporting this mechanism. First, observations in mouse models of graft-versus-host disease have demonstrated that, for MSCs to exert their immunosuppressive effects, they must first undergo natural killer cell/T-cell induced apoptosis [37]. Second, observations in a mouse model showed that injected populations of MSCs were rapidly cleared through monocytic phagocytosis. The monocytes that phagocytosed the MSCs were shown to modulate their phenotype, which changed the course of the immune response [38]. These two observations provide a potential hypothesis for the mechanisms of MSC-mediated immunomodulation, though further studies are required to confirm the details.

2. The Fundamentals of Extracellular Vesicles

EV is an umbrella definition which encompasses all vesicles released or ’shed’ by cells [39]. Typically, EVs have a diameter in the range of 30–2000 nm. They consist of a lipid bi-layer membrane encasing an organelle-free cytosole, which contains a combination of various proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [40][41]. EVs have been recently discovered as a key mechanism of the intercellular communication network. Since EV release was first observed in rat and sheep reticulocytes in the early 1980s [42][43], an ever-growing number of cells have been shown to release EVs as a form of intercellular communication. Almost all mammalian cell types have demonstrated EV secretion including stem cells, neuronal cells, immune cells, and cancer cells [39][44]. EVs have also been isolated from an extensive range of biological fluids including blood, urine, semen, breast milk, cerebrospinal fluid, bile, amniotic fluid, and ascites fluid [44]. Interestingly, EV secretion has been observed in lower eukaryotes and prokaryotes, with speculations that microbial EVs may mediate the host response to infection [44][45].

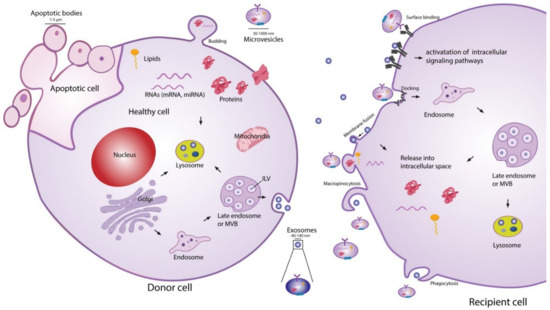

The exact classification of EVs is still evolving, and the current definition of nomenclature is not consistently used in the literature [46][47]. Presently, EV classifications are based on their size and biogenesis [46], with three widely accepted distinct populations. Exosomes are the most widely studied subpopulation of EVs [48]. Although the size range of exosomes has not been consolidated in the literature, it is generally accepted that they have a diameter in the range of 20–150 nm. The biogenesis of exosomes begins with endocytosis, a process of invagination of the plasma membrane to form an endosome. Within the endocytic pathway, endosomes are classified into three sub-populations: early endosomes, late endosomes, and recycling endosomes [49]. Early endosomes which are not destined for secretion, recycling, or degradation become late endosomes. Late endosomal membrane invagination subsequently forms intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) which contain proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. At this point, the late endosome now containing a host of small vesicles is deemed a multivesicular body (MVB) [40]. The MVB has two possible routes, either fusing with the lysosome where its contents will be recycled or fusing with the plasma membrane. The latter releases the ILVs into the extracellular space, where they are now referred to as exosomes. This process is visualised in Figure 1. The formation of ILVs is believed to be mainly regulated by two processes. First, the endosomal membrane is enriched for tetraspanins, specifically CD9 and CD63 [50]. Second, the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRTs) are present during the process of ILV formation. These two processes regulate the initial inward membrane budding of the late endosome, ILV cargo sorting, and subsequent ILV formation. Although it is generally accepted that the ESCRT pathway is the main mechanism governing exosome formation, there exist supplementary mechanisms of ILV formation such as the syndecan–syntenin–ALIX pathway [40]. Since exosomes arise from endosome membrane invagination, they present common proteins associated with this process across all cell types. These proteins include flotillins, GTPases and annexins (membrane transport and fusion); integrins (adhesion); ALIX and the tetraspanins CD9, CD63, CD81, CD82 (MVB formation); and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules (antigen presentation) [51]. Typically, the lipid composition of exosomes mirrors that of their parent cell. Exosomes are commonly enriched with cholesterol, phosphatidylserine, ceramide, and sphingomyelin [52]. Interestingly, the concentration of diacyl-glycerol and phosphatidyl-choline appear to be lower in exosomes than their parent cells [53]. The nucleic acid content of exosomes typically consists of mRNAs, microRNAs (miRNAs), and other non-coding RNAs [51], although genomic and mitochondrial DNA have also been found in exosomes [54][55].

Figure 1. Extracellular vesicle (EV) biogenesis, secretion, and uptake [56]. Exosomes (20–150 nm) are intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) formed by inward budding of the endosomal membrane during maturation of multivesicular body (MVB), which are secreted upon fusion of the MVBs with the plasma membrane. Microvesicles (50–1000 nm) are a heterogeneous group of vesicles with different membranes depending on their origin and morphology. Apoptotic bodies are shedding vesicles derived from apoptotic cells. After their release into the extracellular space, EVs can bind to cell surface receptors to initiate intracellular signalling pathways. EVs can also be internalised through processes such as macropinocytosis and phagocytosis, or by fusion with the plasma membrane. The cargo of EVs consisting of proteins, nucleic acids and lipids are released in the intracellular space or taken up by the endosomal system of the recipient cell. Reproduced with permission from [56].

The second most widely studied subpopulation of EVs are microvesicles (MVs) [48]. It is generally accepted that MVs have a diameter in the range of 50–1000 nm, meaning that they may have a size overlap with exosomes. This creates challenges for purely size-based EV isolation techniques in distinguishing between exosome and MV populations [39]. In contrast to exosomes, MVs are formed through direct shedding from the plasma membrane of the parent cell. The formation of MVs is regulated by aminophospholipid translocases, which control the phospholipid re-distribution in the plasma membrane and the dynamics of cytoskeletal actin-myosin contractions [57]. As MVs form through direct outward budding of the plasma membrane (Figure 1), they share many of the same membrane markers as their parent cell, which may include integrins, selectins, and CD40 ligand [58]. The variations in membrane markers among MVs is a result of the induced changes which occur during the process of nucleation and budding [51]. The cargo carried by MVs, like exosomes, is not simply representative of the cytoplasmic content. Some loading mechanisms such as ARF6 trafficking of proteins and CSE1L nucleic acid export have been identified [59][60]. However, the exact mechanisms of regulation remain incompletely understood and constitute an area of active research. The protein and nucleic acid content of MVs are dependent on the cell type along with the external physiological conditions experienced by the parent cell [40]. A number of proteins are commonly identified in MVs, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), cytoskeletal components, and glycoproteins [51]. Like exosomes, MVs generally contain a combination of mRNAs, miRNAs, and other non-coding RNAs [51], as well as possible genomic and mitochondrial DNA [54][55].

Apoptotic bodies are the final widely recognised subpopulation of EVs. They are by far the largest in size, ranging 500–5000 nm in diameter, and are produced by outward membrane blebbing on the surface of cells undergoing apoptosis [58][61]. There is no evidence that apoptotic bodies play a role in intercellular communication or have a potential therapeutic effect, although they do show potential to be used as disease biomarkers [62].

EV-cell communication can occur through several distinct pathways: lysis of EVs in the extracellular space releasing their contents, direct EV-cell binding, membrane fusion and release of EV contents, and EV uptake into the endocytic system [56][63]. Ligand-receptor binding associated with EV extracellular content release and direct EV binding are believed to be the mechanisms behind several of the biological effects exerted by EVs on cells, such as growth and angiogenic factor delivery [63]. For the nucleic acids or proteins suspended in the EV cytosol to act as messengers in the recipient cell, the EVs must fuse either with the plasma membrane after ligand-receptor binding, or with the endosomal membrane after endocytosis [63]. Endocytosis of EVs is thought to be the most common route of uptake [40][41][63], although several questions remain to be answered about this uptake route. Since the endocytic pathway inevitably ends with degradation or expulsion from the cell, the cargo carried by the EVs must exit the endosome somehow and find its way into the cytoplasm if it is to alter cell composition and function [40]. Although this phenomenon of endosomal escape has been widely observed, the underlying mechanisms are still unclear [40][64][65]. EV–cell communication is known to be involved in an extensive range of biological processes, including modulation of the immune system [66][67], neuro-biological functions such as synaptic plasticity [68], and stem cell differentiation [69][70].

With the extensive role that EVs play in biological processes, it is unsurprising that they are also heavily involved in the pathogenesis of disease. The most in-depth understanding of this concept is in tumour biology [71]. EVs have been shown to have important roles in promoting tumour cell proliferation [72][73], angiogenesis [73][74], ECM remodelling [75], and metastasis [58][75]. Although beyond the scope of this review, there is a great potential in targeting the phenotype altering mechanisms exerted by EVs in tumour biology to help develop new treatment strategies, as well as to apply stem cell-derived EVs as cancer therapeutics [76]. In the field of regenerative medicine, EVs derived from stem cells are shown to replicate the therapeutic properties of the parent cells, and have demonstrated many beneficial effects such as apoptosis suppression [77], promotion of cellular proliferation [78] and angiogenesis [79], and the ability to modulate the diseased cell phenotype to facilitate tissue regeneration [80]. The precise cargo carried by EVs and the mechanisms which facilitate their regenerative potential are still unclear. However, it is known that EV composition is a function of its cellular origin and physiological conditions [81]. By varying factors such as cellular stress, media composition, and physical stimulation, or by enriching certain miRNAs in the parent cells, it may be possible to optimise the EV composition for specific regenerative applications [82][83][84][85].

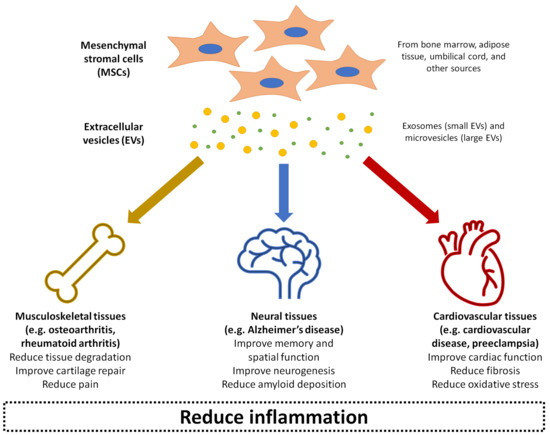

Over the past decade, MSC-derived EVs have been increasingly explored in regenerative medicine to treat disease or promote repair through local delivery in a range of tissue types, including cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, neural, renal, hepatic, lung, dermal, and reproductive tissues [56][86]. It is thought that the MSC-derived EVs can deliver the same anti-inflammatory and trophic effects as the parent cells [87]. Compared to injecting live cells into tissues, MSC-derived EVs bypass potential safety concerns of the MSCs exhibiting uncontrollable behaviour or differentiating into problematic tissue at the site of injection [88]. The EVs also have an additional advantage of presenting minimal toxicity and immunogenicity, even when applied xenogenetically as a large dose at high frequency [89]. The rest of this review will summarise the current state of research into MSC-derived EVs as therapeutic agents for treating a number of inflammation-related conditions: osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, cardiovascular disease, and preeclampsia (Figure 2). For each of these conditions, evidence related to the therapeutic effects of MSC-derived EVs has been collected from a range of experimental studies published within the last ten years, as shown in Table 1. These conditions represent examples of diseases with significant societal impact, where pathogenesis is closely linked with inflammation in musculoskeletal, neural, and cardiovascular tissues as three major body systems. MSC-derived EVs have also demonstrated beneficial effects in other conditions and body systems impacted by inflammation, such as graft-versus-host disease [90], kidney disease [91], liver failure [92], and skin wounds [93], although a detailed discussion of these is beyond the scope of this review.

Figure 2. Summary of the application of mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-derived EVs in treating inflammation-related conditions as covered in this entry: osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, cardiovascular disease, and preeclampsia.

References

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204.

- Netea, M.G.; Balkwill, F.; Chonchol, M.; Cominelli, F.; Donath, M.Y.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Golenbock, D.; Gresnigt, M.S.; Heneka, M.T.; Hoffman, H.M.; et al. A guiding map for inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 826–831.

- Nathan, C.; Ding, A. Nonresolving inflammation. Cell 2010, 140, 871–882.

- McInnes, I.B.; Schett, G. Pathogenetic insights from the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2017, 389, 2328–2337.

- Falk, E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47 (Suppl. 8), C7–C12.

- Zotova, E.; Nicoll, J.A.; Kalaria, R.; Holmes, C.; Boche, D. Inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: Relevance to pathogenesis and therapy. Alzheimer Res. Ther. 2010, 2, 1–9.

- Cho, W.C.; Kwan, C.K.; Yau, S.; So, P.P.; Poon, P.C.; Au, J.S. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of lung cancer. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2011, 15, 1127–1137.

- Greten, F.R.; Grivennikov, S.I. Inflammation and cancer: Triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity 2019, 51, 27–41.

- Nelson, W.G.; De Marzo, A.M.; DeWeese, T.L.; Isaacs, W.B. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2004, 172, S6–S12.

- Holgate, S.T.; Arshad, H.S.; Roberts, G.C.; Howarth, P.H.; Thurner, P.; Davies, D.E. A new look at the pathogenesis of asthma. Clin. Sci. 2010, 118, 439–450.

- Pickup, J.C. Inflammation and activated innate immunity in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 813–823.

- Wada, J.; Makino, H. Inflammation and the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Clin. Sci. 2013, 124, 139–152.

- Goldring, M.B.; Otero, M. Inflammation in osteoarthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2011, 23, 471–478.

- Robinson, W.H.; Lepus, C.M.; Wang, Q.; Raghu, H.; Mao, R.; Lindstrom, T.M.; Sokolove, J. Low-grade inflammation as a key mediator of the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 580.

- Sokolove, J.; Lepus, C.M. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: Latest findings and interpretations. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2013, 5, 77–94.

- Haider, L. Inflammation, iron, energy failure, and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 725370.

- Raison, C.L.; Capuron, L.; Miller, A.H. Cytokines sing the blues: Inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol. 2006, 27, 24–31.

- Van Crombruggen, K.; Zhang, N.; Gevaert, P.; Tomassen, P.; Bachert, C. Pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis: Inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 728–732.

- Bringardner, B.D.; Baran, C.P.; Eubank, T.D.; Marsh, C.B. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008, 10, 287–301.

- Hu, Y.F.; Chen, Y.J.; Lin, Y.J.; Chen, S.A. Inflammation and the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 230–243.

- Libby, P. Inflammatory mechanisms: The molecular basis of inflammation and disease. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, S140–S146.

- Tabas, I.; Glass, C.K. Anti-inflammatory therapy in chronic disease: Challenges and opportunities. Science 2013, 339, 166–172.

- Viswanathan, S.; Shi, Y.; Galipeau, J.; Krampera, M.; Leblanc, K.; Martin, I.; Nolta, J.; Phinney, D.; Sensebe, L. Mesenchymal stem versus stromal cells: International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT®) Mesenchymal Stromal Cell committee position statement on nomenclature. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 1019–1024.

- Mendicino, M.; Bailey, A.M.; Wonnacott, K.; Puri, R.K.; Bauer, S.R. MSC-based product characterization for clinical trials: An FDA perspective. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 141–145.

- Iyer, S.S.; Rojas, M. Anti-inflammatory effects of mesenchymal stem cells: Novel concept for future therapies. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2008, 8, 569–581.

- Murphy, M.B.; Moncivais, K.; Caplan, A.I. Mesenchymal stem cells: Environmentally responsive therapeutics for regenerative medicine. Exp. Mol. Med. 2013, 45, e54.

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, H.; Carter, J.E.; Chang, J.W.; Oh, W.; Yang, Y.S.; Suh, J.-G.; Lee, B.-H.; Jin, H.K. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells improve neuropathology and cognitive impairment in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model through modulation of neuroinflammation. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 588–602.

- Wakitani, S.; Imoto, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Saito, M.; Murata, N.; Yoneda, M. Human autologous culture expanded bone marrow mesenchymal cell transplantation for repair of cartilage defects in osteoarthritic knees. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2002, 10, 199–206.

- Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, B.; Li, B. Exosomes derived from adipose tissue, bone marrow, and umbilical cord blood for cardioprotection after myocardial infarction. J. Cell. Biochem. 2020, 121, 2089–2102.

- Gupta, P.K.; Das, A.K.; Chullikana, A.; Majumdar, A.S. Mesenchymal stem cells for cartilage repair in osteoarthritis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2012, 3, 1–9.

- Von Bahr, L.; Batsis, I.; Moll, G.; Hägg, M.; Szakos, A.; Sundberg, B.; Uzunel, M.; Ringden, O. Le Blanc, K. Analysis of tissues following mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in humans indicates limited long‐term engraftment and no ectopic tissue formation. Stem Cells 2012, 30, 1575–1578.

- Barry, F. MSC therapy for osteoarthritis: An unfinished story. J. Orthop. Res. 2019, 37, 1229–1235.

- Doorn, J.; Moll, G.; Le Blanc, K.; Van Blitterswijk, C. De Boer, J. Therapeutic applications of mesenchymal stromal cells: Paracrine effects and potential improvements. Tissue Eng. Part B: Rev. 2012, 18, 101–115.

- Ferreira, J.R.; Teixeira, G.Q.; Santos, S.G.; Barbosa, M.A.; Almeida-Porada, G.; Gonçalves, R.M. Mesenchymal stromal cell secretome: Influencing therapeutic potential by cellular pre-conditioning. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2837.

- Gnecchi, M.; Danieli, P.; Malpasso, G.; Ciuffreda, M.C. Paracrine mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cells in tissue repair. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1416, 123–146.

- Mancuso, P.; Raman, S.; Glynn, A.; Barry, F.; Murphy, J.M. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for osteoarthritis: The critical role of the cell secretome. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 9.

- Galleu, A.; Riffo-Vasquez, Y.; Trento, C.; Lomas, C.; Dolcetti, L.; Cheung, T.S.; von Bonin, M.; Barbieri, L.; Halai, K.; Ward, S.; et al. Apoptosis in mesenchymal stromal cells induces in vivo recipient-mediated immunomodulation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaam7828.

- de Witte, S.F.; Luk, F.; Sierra Parraga, J.M.; Gargesha, M.; Merino, A.; Korevaar, S.S.; Shankar, A.S.; O’Flynn, L.; Elliman, S.J.; Roy, D. Immunomodulation by therapeutic mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) is triggered through phagocytosis of MSC by monocytic cells. Stem Cells 2018, 36, 602–615.

- Raposo, G.; Stoorvogel, W. Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 200, 373–383.

- Abels, E.R.; Breakefield, X.O. Introduction to extracellular vesicles: Biogenesis, RNA cargo selection, content, release, and uptake. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 36, 301–312.

- Mulcahy, L.A.; Pink, R.C.; Carter, D.R.F. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 24641.

- Harding, C.; Heuser, J.; Stahl, P. Endocytosis and intracellular processing of transferrin and colloidal gold-transferrin in rat reticulocytes: Demonstration of a pathway for receptor shedding. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1984, 35, 256–263.

- Pan, B.T.; Johnstone, R.M. Fate of the transferrin receptor during maturation of sheep reticulocytes in vitro: Selective externalization of the receptor. Cell 1983, 33, 967–978.

- Rani, S.; Ryan, A.E.; Griffin, M.D.; Ritter, T. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: Toward cell-free therapeutic applications. Mol. Ther. 2015, 23, 812–823.

- Tsatsaronis, J.A.; Franch-Arroyo, S.; Resch, U.; Charpentier, E. Extracellular vesicle RNA: A universal mediator of microbial communication? Trends Microbiol. 2018, 26, 401–410.

- van der Pol, E.; Boing, A.N.; Harrison, P.; Sturk, A.; Nieuwland, R. Classification, functions, and clinical relevance of extracellular vesicles. Pharmacol. Rev. 2012, 64, 676–705.

- Witwer, K.W.; Buzas, E.I.; Bemis, L.T.; Bora, A.; Lasser, C.; Lotvall, J.; Nolte-’t Hoen, E.N.; Piper, M.G.; Sivaraman, S.; Skog, J.; et al. Standardization of sample collection, isolation and analysis methods in extracellular vesicle research. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2013, 2, 20360.

- Lötvall, J.; Hill, A.F.; Hochberg, F.; Buzás, E.I.; Di Vizio, D.; Gardiner, C.; Gho, Y.S.; Kurochkin, I.V.; Mathivanan, S.; Quesenberry, P.; et al. Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: A position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 26913.

- Grant, B.D.; Donaldson, J.G. Pathways and mechanisms of endocytic recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 597–608.

- Pols, M.S.; Klumperman, J. Trafficking and function of the tetraspanin CD63. Exp. Cell Res. 2009, 315, 1584–1592.

- Kalra, H.; Drummen, G.P.; Mathivanan, S. Focus on extracellular vesicles: Introducing the next small big thing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 170.

- Llorente, A.; Skotland, T.; Sylvanne, T.; Kauhanen, D.; Rog, T.; Orlowski, A.; Vattulainen, I.; Ekroos, K.; Sandvig, K. Molecular lipidomics of exosomes released by PC-3 prostate cancer cells. Biochim. ET Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gen. Subj. 2013, 1831, 1302–1309.

- Laulagnier, K.; Motta, C.; Hamdi, S.; Roy, S.; Fauvelle, F.; Pageaux, J.F.; Kobayashi, T.; Salles, J.P.; Perret, B.; Bonnerot, C.; et al. Mast cell- and dendritic cell-derived exosomes display a specific lipid composition and an unusual membrane organization. Biochem. J. 2004, 380, 161–171.

- Guescini, M.; Genedani, S.; Stocchi, V.; Agnati, L.F. Astrocytes and Glioblastoma cells release exosomes carrying mtDNA. J. Neural Transm. 2010, 117, 1–4.

- Waldenstrom, A.; Genneback, N.; Hellman, U.; Ronquist, G. Cardiomyocyte microvesicles contain DNA/RNA and convey biological messages to target cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34653.

- Varderidou-Minasian, S.; Lorenowicz, M.J. Mesenchymal stromal/stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in tissue repair: Challenges and opportunities. Theranostics 2020, 10, 5979–5997.

- Akers, J.C.; Gonda, D.; Kim, R.; Carter, B.S.; Chen, C.C. Biogenesis of extracellular vesicles (EV): Exosomes, microvesicles, retrovirus-like vesicles, and apoptotic bodies. J. Neuro Oncol. 2013, 113, 1–11.

- El Andaloussi, S.; Mäger, I.; Breakefield, X.O.; Wood, M.J.A. Extracellular vesicles: Biology and emerging therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 347.

- Liao, C.-F.; Lin, S.-H.; Chen, H.-C.; Tai, C.-J.; Chang, C.-C.; Li, L.-T.; Yeh, C.-M.; Yeh, K.-T.; Chen, Y.-C.; Hsu, T.-H. CSE1L, a novel microvesicle membrane protein, mediates Ras-triggered microvesicle generation and metastasis of tumor cells. Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 1269–1280.

- Tricarico, C.; Clancy, J. D’Souza-Schorey, C. Biology and biogenesis of shed microvesicles. Small Gtpases 2017, 8, 220–232.

- Crescitelli, R.; Lasser, C.; Szabo, T.G.; Kittel, A.; Eldh, M.; Dianzani, I.; Buzas, E.I.; Lotvall, J. Distinct RNA profiles in subpopulations of extracellular vesicles: Apoptotic bodies, microvesicles and exosomes. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2013, 2, 20677.

- Hauser, P.; Wang, S.; Didenko, V.V. Apoptotic bodies: Selective detection in extracellular vesicles. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1554, 193–200.

- Maas, S.L.N.; Breakefield, X.O.; Weaver, A.M. Extracellular vesicles: Unique intercellular delivery vehicles. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 172–188.

- Montecalvo, A.; Larregina, A.T.; Shufesky, W.J.; Beer Stolz, D.; Sullivan, M.L.; Karlsson, J.M.; Baty, C.J.; Gibson, G.A.; Erdos, G.; Wang, Z. Mechanism of transfer of functional microRNAs between mouse dendritic cells via exosomes. Blood 2012, 119, 756–766.

- Pegtel, D.M.; Cosmopoulos, K.; Thorley-Lawson, D.A.; van Eijndhoven, M.A.; Hopmans, E.S.; Lindenberg, J.L.; de Gruijl, T.D.; Wurdinger, T.; Middeldorp, J.M. Functional delivery of viral miRNAs via exosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6328–6333.

- Clayton, A.; Mitchell, J.P.; Mason, M.D.; Tabi, Z. Human tumor-derived exosomes selectively impair lymphocyte responses to interleukin-2. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 7458–7466.

- Sprague, D.L.; Elzey, B.D.; Crist, S.A.; Waldschmidt, T.J.; Jensen, R.J.; Ratliff, T.L. Platelet-mediated modulation of adaptive immunity: Unique delivery of CD154 signal by platelet-derived membrane vesicles. Blood 2008, 111, 5028–5036.

- Chivet, M.; Hemming, F.; Fraboulet, S.; Sadoul, R. Emerging role of neuronal exosomes in the central nervous system. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 145.

- Aliotta, J.M.; Pereira, M.; Li, M.; Amaral, A.; Sorokina, A.; Dooner, M.S.; Sears, E.H.; Brilliant, K.; Ramratnam, B.; Hixson, D.C. Stable cell fate changes in marrow cells induced by lung-derived microvesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2012, 1, 18163.

- Aliotta, J.M.; Sanchez‐Guijo, F.M.; Dooner, G.J.; Johnson, K.W.; Dooner, M.S.; Greer, K.A.; Greer, D.; Pimentel, J.; Kolankiewicz, L.M.; Puente, N. Alteration of marrow cell gene expression, protein production, and engraftment into lung by lung‐derived microvesicles: A novel mechanism for phenotype modulation. Stem Cells 2007, 25, 2245–2256.

- Rak, J.; Guha, A. Extracellular vesicles–vehicles that spread cancer genes. Bioessays 2012, 34, 489–497.

- Hosseini-Beheshti, E.; Choi, W.; Weiswald, L.-B.; Kharmate, G.; Ghaffari, M.; Roshan-Moniri, M.; Hassona, M.D.; Chan, L.; Chin, M.Y.; Tai, I.T. Exosomes confer pro-survival signals to alter the phenotype of prostate cells in their surrounding environment. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 14639.

- Skog, J.; Würdinger, T.; Van Rijn, S.; Meijer, D.H.; Gainche, L.; Curry, W.T.; Carter, B.S.; Krichevsky, A.M.; Breakefield, X.O. Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 1470–1476.

- Al-Nedawi, K.; Meehan, B.; Kerbel, R.S.; Allison, A.C.; Rak, J. Endothelial expression of autocrine VEGF upon the uptake of tumor-derived microvesicles containing oncogenic EGFR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3794–3799.

- Sidhu, S.S.; Mengistab, A.T.; Tauscher, A.N.; LaVail, J.; Basbaum, C. The microvesicle as a vehicle for EMMPRIN in tumor–stromal interactions. Oncogene 2004, 23, 956–963.

- Parfejevs, V.; Sagini, K.; Buss, A.; Sobolevska, K.; Llorente, A.; Riekstina, U.; Abols, A. Adult stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in cancer treatment: Opportunities and challenges. Cells 2020, 9, 1171.

- Gatti, S.; Bruno, S.; Deregibus, M.C.; Sordi, A.; Cantaluppi, V.; Tetta, C.; Camussi, G. Microvesicles derived from human adult mesenchymal stem cells protect against ischaemia-reperfusion-induced acute and chronic kidney injury. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011, 26, 1474–1483.

- Herrera, M.; Fonsato, V.; Gatti, S.; Deregibus, M.C.; Sordi, A.; Cantarella, D.; Calogero, R.; Bussolati, B.; Tetta, C.; Camussi, G. Human liver stem cell‐derived microvesicles accelerate hepatic regeneration in hepatectomized rats. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2010, 14, 1605–1618.

- Deregibus, M.C.; Cantaluppi, V.; Calogero, R.; Lo Iacono, M.; Tetta, C.; Biancone, L.; Bruno, S.; Bussolati, B.; Camussi, G. Endothelial progenitor cell derived microvesicles activate an angiogenic program in endothelial cells by a horizontal transfer of mRNA. Blood 2007, 110, 2440–2448.

- Ratajczak, J.; Miekus, K.; Kucia, M.; Zhang, J.; Reca, R.; Dvorak, P.; Ratajczak, M. Embryonic stem cell-derived microvesicles reprogram hematopoietic progenitors: Evidence for horizontal transfer of mRNA and protein delivery. Leukemia 2006, 20, 847–856.

- de Jong, O.G.; Verhaar, M.C.; Chen, Y.; Vader, P.; Gremmels, H.; Posthuma, G.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Gucek, M. van Balkom, B.W. Cellular stress conditions are reflected in the protein and RNA content of endothelial cell-derived exosomes. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2012, 1, 18396.

- Lo Sicco, C.; Reverberi, D.; Balbi, C.; Ulivi, V.; Principi, E.; Pascucci, L.; Becherini, P.; Bosco, M.C.; Varesio, L.; Franzin, C. Mesenchymal stem cell‐derived extracellular vesicles as mediators of anti‐inflammatory effects: Endorsement of macrophage polarization. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017, 6, 1018–1028.

- Mao, G.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Chang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Liao, W.; Kang, Y. Exosomes derived from miR-92a-3p-overexpressing human mesenchymal stem cells enhance chondrogenesis and suppress cartilage degradation via targeting WNT5A. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 1–13.

- Tao, S.C.; Yuan, T.; Zhang, Y.L.; Yin, W.J.; Guo, S.C.; Zhang, C.Q. Exosomes derived from miR-140-5p-overexpressing human synovial mesenchymal stem cells enhance cartilage tissue regeneration and prevent osteoarthritis of the knee in a rat model. Theranostics 2017, 7, 180–195.

- Wu, J.; Kuang, L.; Chen, C.; Yang, J.; Zeng, W.N.; Li, T.; Chen, H.; Huang, S.; Fu, Z.; Li, J.; et al. miR-100-5p-abundant exosomes derived from infrapatellar fat pad MSCs protect articular cartilage and ameliorate gait abnormalities via inhibition of mTOR in osteoarthritis. Biomaterials 2019, 206, 87–100.

- Lamichhane, T.N.; Sokic, S.; Schardt, J.S.; Raiker, R.S.; Lin, J.W.; Jay, S.M. Emerging roles for extracellular vesicles in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2015, 21, 45–54.

- Li, J.J.; Hosseini-Beheshti, E.; Grau, G.E.; Zreiqat, H.; Little, C.B. Stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles for treating joint injury and osteoarthritis. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 261.

- Caplan, H.; Olson, S.D.; Kumar, A.; George, M.; Prabhakara, K.S.; Wenzel, P.; Bedi, S.; Toledano-Furman, N.E.; Triolo, F. Kamhieh-Milz, J. Mesenchymal stromal cell therapeutic delivery: Translational challenges to clinical application. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1645.

- Zhu, X.; Badawi, M.; Pomeroy, S.; Sutaria, D.S.; Xie, Z.; Baek, A.; Jiang, J.; Elgamal, O.A.; Mo, X.; Perle, K.L.; et al. Comprehensive toxicity and immunogenicity studies reveal minimal effects in mice following sustained dosing of extracellular vesicles derived from HEK293T cells. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2017, 6, 1324730.

- Kordelas, L.; Rebmann, V.; Ludwig, A.K.; Radtke, S.; Ruesing, J.; Doeppner, T.R.; Epple, M.; Horn, P.A.; Beelen, D.W.; Giebel, B. MSC-derived exosomes: A novel tool to treat therapy-refractory graft-versus-host disease. Leukemia 2014, 28, 970–973.

- Aghajani Nargesi, A.; Lerman, L.O.; Eirin, A. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles for kidney repair: Current status and looming challenges. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 273.

- Wang, J.; Cen, P.; Chen, J.; Fan, L.; Li, J.; Cao, H.; Li, L. Role of mesenchymal stem cells, their derived factors, and extracellular vesicles in liver failure. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 137.

- Casado-Díaz, A.; Quesada-Gómez, J.M.; Dorado, G. Extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) in regenerative medicine: Applications in skin wound healing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 146–146.