| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Håkon Eidsvåg | + 4417 word(s) | 4417 | 2021-03-22 08:43:43 |

Video Upload Options

Hydrogen produced from water using photocatalysts driven by sunlight is a sustainable way to overcome the intermittency issues of solar power and provide a green alternative to fossil fuels. TiO2 has been used as a photocatalyst since the 1970s due to its low cost, earth abundance, and stability. There has been a wide range of research activities in order to enhance the use of TiO2 as a photocatalyst using dopants, modifying the surface, or depositing noble metals. However, the issues such as wide bandgap, high electron-hole recombination time, and a large overpotential for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) persist as a challenge. Here, we review state-of-the-art experimental and theoretical research on TiO2 based photocatalysts and identify challenges that have to be focused on to drive the field further. We conclude with a discussion of four challenges for TiO2 photocatalysts—non-standardized presentation of results, bandgap in the ultraviolet (UV) region, lack of collaboration between experimental and theoretical work, and lack of large/small scale production facilities. We also highlight the importance of combining computational modeling with experimental work to make further advances in this exciting field.

1. Introduction

Over the last years, there has been a steadily increasing focus on clean, renewable energy sources as a priority to hinder the irreversible climate change the world is facing and to meet the continuously growing energy demand [1]. One hour of solar energy can satisfy the energy consumption of the whole world for a year [2]. Hence, direct harvesting of solar light and its conversion into electrical energy with photovoltaic cells or chemical energy by photoelectrochemical reactions are the most relevant technologies to overcome this challenge. Conventionally, both technologies rely on the collection of light in semiconductor materials with appropriate bandgaps matching the solar spectrum, and thus providing a high-energy conversion efficiency.

Unfortunately, the technology has drawbacks, which prevent it from overtaking non-renewable energy as the main energy source. A major issue is the uneven power distribution caused by varying solar radiation and a lack of proper storage alternatives. As a solution to this problem, the focus is moving toward research on storage options for the produced electricity, which we can divide into mechanical and electrochemical storage systems. For example, in Oceania, pumped hydroelectricity (mechanical) is the most common storage system for excess electricity [3]. Different batteries (lithium–ion, sodium–sulfur (S), vanadium, etc.), hydrogen fuel cells, and supercapacitors are the current focus areas for electrochemical storage [3]. There are several reasons for choosing hydrogen as a way to store solar energy, namely, (1) there is a high abundance of hydrogen from renewable sources; (2) it is eco-friendly when used; (3) hydrogen has a high-energy yield, and (4) it is easy to store as either a gas or a liquid [4,5,6].

The high energy yield and ease of storage make hydrogen viable as fuel for the long transport sector; airplanes, cruise ships, trailers, and cargo ships [7,8]. The realization of a green energy shipping fleet could alone yearly cut 2.5% of global greenhouse emissions (GHG) [9]. However, to succeed in this strategy, hydrogen must be produced in a clean and renewable way.

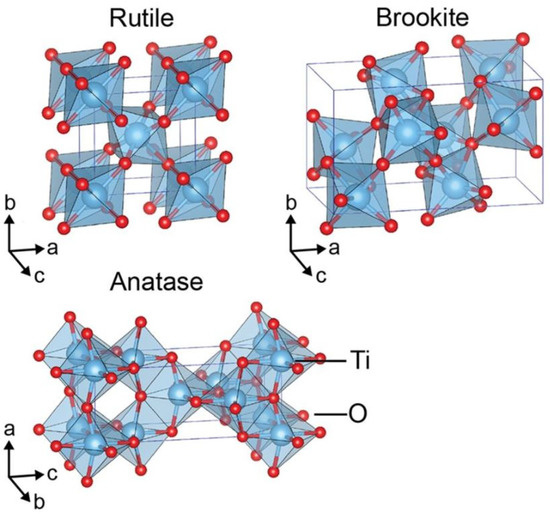

As water splitting got the attention of the researchers in the 1970s, titanium dioxide became the most prominent photocatalyst used [10]. There are several good reasons for this: low cost, chemical stability, earth abundance, and nontoxicity [11]. However, TiO2 also sports a wide bandgap (3.0–3.2 eV), which reduces the potential for absorption of visible light [11]. Due to TiO2s structural and chemical properties, it is possible to engineer the bandgap, light absorption properties, recombination time, etc. by increasing the active sites and improving the electrical conductivity [12]. TiO2 exists in several different polymorphs that all behave differently. The most common ones are rutile, brookite, and anatase as shown in Figure 1. Rutile and anatase TiO2 are the most used polymorphs for photocatalytic water splitting; nevertheless, some attempts with amorphous TiO2 (aTiO2) have been made as shown in Figure 2.

2. Solar-Driven Hydrogen Production

Most of the commercial production of hydrogen stems from four sources: natural gas, coal, oil, and electrolysis. Of these, steam reforming alone stands for 48% of the world’s hydrogen production, while coal contributes 18%, oil 30%, and electrolysis 4% [17]. The first three hydrogen production processes are energy-consuming and use non-renewable energy sources, which is unattractive for environment protection and climate change [18,19]. However, the production of hydrogen by electrolysis requires only water and electrical current. To have green hydrogen, produced friendly to the environment, we propose to use renewable energy sources—wind, hydro, and solar power—to produce the electric current needed for the electrolysis of water. Solar power is ideal due to the high amount of incoming energy. There are several functional methods used in driving the electrolysis process, i.e., thermochemical water splitting [20], photo-biological water splitting [21], and photocatalytic water splitting [22]. Furthermore, photocatalytic water splitting (PWS) is considered the best option, due to the following reasons: (1) PWS has a good solar-hydrogen conversion efficiency, (2) it has a low production cost, (3) oxygen and hydrogen can easily be separated during the PWS process, and (4) hydrogen electrolysis could be used on both small- and large-scale facilities [4,22,23].

2.1. Photocatalytic Water Splitting (PWS)

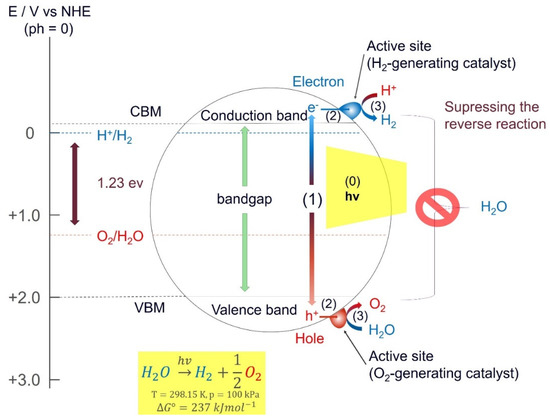

The photocatalytic process splits water (H2O) into hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2) in the presence of a catalyst and natural light; it is an artificial photosynthesis method. Figure 3 shows a schematic illustration of the major steps involved in the process of photocatalytic water splitting. In the first step (1), electron–hole pairs are generated in the presence of irradiation. This is carried out by utilizing the semiconducting nature of the photocatalyst to excite electrons from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB). Photons with energies larger than the bandgap can excite electrons from the VB to the CB. The second step (2) consists of charge separation and migration of the photogenerated electron-hole pairs. Ideally, all electrons and holes reach the surface without recombination to maximize the efficiency of the photocatalyst. In the final step (3), the electrons, which move from the CB to the surface of the catalyst participate in a reduction reaction and generate hydrogen, and the holes diffuse from the VB to the surface of the photocatalyst involved in an oxidation reaction to form oxygen. In general, the efficiency of the catalyst can be enhanced by including dopants or co-catalysts that include metals or metal oxides, such as Pt, NiO, and RuO2, which can act as the active sites via enhancing electron mobility. The redox and oxidations reactions on the surface of the photocatalyst are described by the following equations [24]:

Overall reaction: H2O+1.23 eV→H2+12O2.

The process of water splitting is highly endothermic and requires a Gibbs free energy of 1.23 eV per electron, which corresponds to light with a wavelength of 1008 nm. This means that the photocatalyst must have a bandgap > 1.23 eV, or else the electrons will not have enough energy to start the reaction. In practice, this limit should be 1.6 eV to 1.8 eV due to some overpotentials [24]. Naturally, it should not be too high either, as that would reduce the amount of visible light the photocatalyst can absorb. This means that it is important to find suitable catalysts with a bandgap between 1.6–2.2 eV to ensure maximum absorption of the incoming light. Another important factor regarding the efficiency of a photocatalyst is the recombination time, i.e., the time it takes for an electron to recombine with a hole. If recombination occurs before the electrons can reach the surface and interact with the water molecules, the energy gets wasted and no redox reaction takes place. Unfortunately, there are only a few materials with sufficient recombination time and a satisfactory bandgap that have been identified. However, a recent study by Takata et. al. demonstrates that it is possible to achieve water splitting without any charge recombination losses [26]. With SrTiO3 as the photocatalyst loaded with Rh, Cr, and Co as cocatalysts, they achieved an external quantum efficiency up to 96% at wavelengths between 350 nm and 360 nm [26]. This is equivalent to having an internal quantum efficiency of almost unity. The requirements for having an efficient photocatalyst can be summarized in the solar–hydrogen conversion efficiency (STH) equation [27] as follows:

The STH conversion efficiency depends on (1) the efficiencies of light absorption (ηA), (2) charge separation (ηCS), (3) charge transport (ηCT), and (4) charge collection/reaction efficiency (ηCR). The efficiency of the photocatalyst depends on several factors and they are elaborated in the following section.

2.2. Important Aspects of Photocatalytic Efficiency for Nanomaterials

There are several ways to improve and modify the fundamental properties of a photocatalyst by focusing on its shape, size, order, uniformity, and morphology.

2.2.1. Crystallinity

Research has shown that the crystallinity of the material affects its optoelectronic properties [28,29]. Structures with a high crystallinity perform better than amorphous variations of the same material. The increase in crystallinity reduces the number of defects in the structures and thus decreases the electron-hole recombination sites, which leads to a better catalytic activity [30,31,32,33]. Liu et al. studied the effect of crystalline TiO2 nanotubes against that of amorphous TiO2 nanotubes and found that better photocurrent properties were attained with the crystalline structures due to the lower amount of electron-hole recombination [34]. In another study, enhanced hydrogen production was obtained using extremely ordered nanotubular TiO2 arrays [35].

2.2.2. Dimensionality

Nanomaterials can be classified into four different categories depending on their dimensionality—zero-dimensional (0D), one-dimensional (1D), two-dimensional (2D), and three-dimensional (3D) [36,37]. Zero-dimensional (0D) nanostructures used in PWS are primarily quantum dots (QDs) and hollow shells. In general, QDs are used to decorate the photocatalyst because they increase the visible light absorption and reduce the electron-hole recombination [38,39,40]. One-dimensional (1D) structures include nanorods, nanotubes, and nanowires, which are all attractive for photocatalysts. It is found that nanorod and nanowire arrays result in a more efficient photogenerated electron transport and collection [41,42,43]. On the other hand, nanotubes have a higher surface area for redox reactions compared to nanorods or nanowires although they have less material for light absorption [44,45]. Two-dimensional (2D) nanostructures have a high surface area and a small thickness that reduces the travel distance for generated holes. This results in efficient light harvesting. Lastly, 3D nanostructures are promising candidates for PWS because they can be designed into high-performance photoanodes [27]. In general, it is possible to design and create nanostructures that cater to specific tasks.

2.2.3. Temperature and Pressure

Temperature and pressure during the production phase will affect the resulting properties of a photocatalyst. Research shows that by varying the pressure, the STH performance of the catalyst will change [46]. Another research group found that by using a low-temperature thermal treatment process the charge transfer resistance could be reduced [47].

2.2.4. Size

As mentioned TiO2 exist in three phases, anatase (tetragonal; a = 3.7845 Å; c = 9.5143 Å), rutile (tetragonal; a = 4.5937 Å; c = 2.9587 Å), and brookite (orthorhombic; a = 5.4558 Å; b = 9.1819 Å; c = 5.1429 Å). Among the three different crystalline phases of TiO2, anatase exhibits the highest stability for particle size less than 11 nm, whereas rutile shows thermodynamic stability for particle size greater than 35 nm, and brookite is stable in the size range of 11–35 nm. The size of the nanomaterials and cocatalyst can alter the overall performance of the system. Smaller particles are dominated by electrokinetics and are thus more suited for photocatalysis. Alternatively, larger particles are better suited for photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting because they have a lower electron–hole recombination rate [48]. The size of the particles also influences the electron-hole recombination time. In larger particles the travel distance to the active sites on the surface becomes longer, thus increasing the probability for electron-hole recombination. This probability is decreased in smaller particles due to the shorter migration distance [49,50].

2.2.5. Bandgap

The bandgap is one of the most important properties of the photocatalyst. It is defined as the energy needed for an electron to move from the valence band maximum (VBM) to the conduction band minimum (CBM) in a semiconductor. In addition to a fitting bandgap, the CBM must be more negative than the redox potential of H+/H2 (0 V vs. normal hydrogen electrode (NHE)), while the VBM must be more positive than the redox potential of O2/H2O (1.23 V). Therefore, the theoretical minimum bandgap for water splitting is 1.23 eV. Nanomaterials are used to tune the band positions and the bandgap toward the appropriate range of 1.6 eV to 2.2 eV [51,52,53].

2.2.6. pH Dependency

The pH value of the solution in which the photocatalyst is placed affects the end STH efficiency [54]. It will similarly affect the stability and lifetime of the catalyst. Photoelectrochemical water splitting is very dependent on the pH of the electrolyte solution, which determines the net total charge adsorbed at the surface of the catalyst. The migration of ions during the reactions may weaken the surface of the electrode. The electrode incorporated with nanomaterials exhibits better stability in different pH conditions, however, it was evident that the stability was further improved when the solution is buffered [55,56,57].

2.2.7. Light

It is important that the light source be specified, as semiconductors doped with nanomaterials can absorb both infrared and UV light in addition to visible light [58].

3. Experimental Research

Recent advances in fabrication techniques have made it possible to deposit ultra-thin films, various-sized nanoparticles, and to create nanowires, nanorods, nanobelts, etc. This has made it possible to utilize interesting properties of nanostructure and improve TiO2 photocatalysts.

3.1. Metal Dopants

An interesting phenomenon that could be exploited to increase the solar absorption is the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) effect and localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect, where metal nanoparticles absorb incoming light outside the bandgap of the catalyst. The generated electrons will then be transferred to the surface of the photocatalyst and take part in the oxidation and reduction of the water molecules. To achieve this, one must add metal nanoparticles to the surface of the photocatalyst and let them absorb incoming radiation. Several attempts utilizing metal dopants on TiO2 photocatalysts have revealed an increase in light absorption due to SPR/LSPR.

Zhao Li et al. worked on aluminum-doped TiO2, and they report an increased PEC efficiency due to the LSPR effect [123]. Interestingly enough, they also found that an ultrathin (0.8–2.5 nm) layer of Al2O3 is formed naturally, which works as a protective layer against Al NPs corrosion and in reducing the surface charge recombination [123].

A similar increase in light absorption due to SPR and LSPR can be found using Co, Ni, titanium nitride (TiN), Au, Cu, or Ag dopants [124,125,126,127,128,129]. Nickel was also found to improve the separation of electron–hole pairs [125], while TiN assisted with charge generation, separation transportation, and injection efficiency [126]. Another advantage of the Ag nanoparticles is that they lower the charge carrier recombination rate [129]. In their research on Au dopants, Jinse Park et al. used ZnO–TiO2 nanowires and found that the nanowires themselves excel in charge separation and transportation [127]. Shuai Zhang et al. used a Cu doped TiO2 nanowire film, which showcased clear improvement in photocurrent density due to the unique architecture [128].

In a similar experiment, Jie Liu et al. used Co3O4 quantum dots on TiO2 nanobelts and achieved H2 and O2 production rates of 41.8 and 22.0 µmol/hg [130]. The QDs favored transfer and accommodation of photo-generated electrons, in addition, to inhibit the recombination of charge carriers [130].

Doping could also induce a Schottky junction in the photocatalyst, which could help increase the charge transfer and help separate the photogenerated electrons and holes. He et al. showed this, using TiO2 nanowire decorated with Pd NPs and achieving a photocurrent density of 1.4 mA/cm2 [131]. The use of platinum within TiO2 based photocatalysts is well known, and Lichao Wang et al. showed that by creating a Pt/TiO2 photocatalyst, an H2 production rate of 7410 µmol/gh is achievable [132].

Complex dopants have also been used on TiO2, in addition to nanostructures. This makes it possible to combine the properties of the various dopants on TiO2. In an attempt to increase the hydrogen production of TiO2, Ejaz Hussain et al. doped TiO2 with Pd–BaO NPs [133]. They achieved an H2 production of 29.6 mmol/hg in a solution of 5% ethanol and 95% water [133]. Hussain et al. took advantage of the inherent high catalytic activity of the Pd nanoparticles, and the fact that barium oxide (BaO) enhances the electron transfer from the semiconductor band to the Pd centers [133]. In a similar approach, cadmium sulfide (CdS) was incorporated into a TiO2 photoanode [134]. This utilized the suppression of electron-hole recombination and efficient charge separation/diffusion due to the nanorod structure, in addition to the SPR effect from the dopants [134]. Instead of doping TiO2 only with CdS, it could be combined with tin (IV) oxide (SnO2) nanosheets. The reason for this is that TiO2 reduces the charge recombination between Cds and SnO2 [135]. Thus, the number of electrons and holes reaching the surface and participating in the reduction or oxidation process increases.

It is also possible to dope TiO2 with Ti3+ and Ni to improve the overall efficiency; in fact, Ti3+/Ni co-doped TiO2 nanotubes have a bandgap of 2.84 eV [136]. This is roughly 12% narrower than that of pure TiO2 and could be explained by the SPR effect.

Lately, there has been some research devoted to black titanium dioxide. Mengqiao Hu et al. used Ti3+ self-doped mesoporous black TiO2/SiO2/g–C3N4 sheets [137]. The system has a bandgap of ~2.25 eV and photocatalytic hydrogen evolution of 572.6 µmol/gh. This is all due to the unique mesoporous framework enhancing the adsorption of pollutants and favoring the mass transfer, Ti3+ self-doping reducing the bandgap, and extending the photoresponse to the visible light region [137].

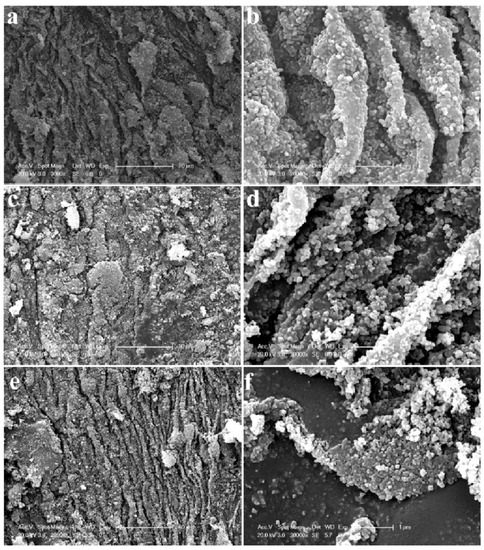

Through modifying the TiO2 NPs with 2D molybdenum disulfide (MoSe2), Lulu Wu et al. achieved a hydrogen production rate of 5.13 µmol/h for samples with 0.1 wt.% MoSe2 [138]. They created MoSe2 nanosheets, which were then combined with TiO2 nanoparticles to create an efficient photocatalyst (Figure 8), by taking advantage of the wide light response and rapid charge migration ability of 2D nanosheets MoSe2. A slightly different approach would be to wrap rutile TiO2 nanorods with amorphous Ta2OxNy to achieve an optical bandgap of 2.86 eV with band edge positions suitable for water splitting [139].

Figure 8. SEM images of MoSe2 with TiO2 nanoparticles synthesised using a simple hydrothermal method; (a,b) 0.025%, (c,d) 0,05%, and (e,f) 0.1% mass ratio of MoSe2:TiO2. Reprinted with permission from [138]. Copyright 2019, with permission from Elsevier.

Bismuth vanadate (BiVO4), iron (III) oxide/hematite (Fe2O3), and bismuth ferrite (BiFeO3) are materials with interesting properties for solar-driven water splitting. They all have low bandgaps, which could help with visible light absorption, and are both simple and inexpensive materials [140,141,142]

Xin Wu et al. utilized BiFeO3 (BFO) on top of TiO2 and found a photocurrent density as high as 11.25 mA/cm2, 20 times higher than that of bare TiO2 [143]. The improvement is mainly due to the heterostructure of BFO/TiO2 and the ferroelectric polarization due to the introduction of BFO, which could lead to upward bending at the interface and thus effectively drive the separation and transportation of photogenerated carriers [143].

Bismuth vanadate is most often used together with a dopant. For example, Jia et al. used W to dope TiO2/BiVO4 nanorods and obtained a bandgap of 2.4 eV [144]. In addition, Wengfeng Zhou et al. synthesized an ultrathin Ti/TiO2/BiVO4 nanosheet heterojunction [145]. It had an enhanced photocatalytic effect due to the formation of a built-in electric field in the heterojunction between TiO2 and BiVO4 [145]. Using Co, Pi Quan Liu et al. modified a TiO2/BiVO4 composite photoanode, which shows improved visible light absorption and a more efficient charge transfer relay [146]. By combining FeOOH/TiO2/BiVO4, Xiang Yin et al. created a photoanode that led to a hydrogen production rate of 2.36 µmol/cm2 after testing for 2.5 h [147].

However, it is possible to use BiVO4 without a dopant BiV because O4 and TiO2 naturally complement each other. It allows for the exploitation of the excellent absorption properties of BiVO4 to produce highly reductive electrons through TiO2 sensitization under visible light [148]. Another example of this is how Ahmad Radzi et al. deposited BiVO4 on TiO2 to increase PEC efficiency [149].

Hematite is usually combined with more complex structures, for example, 3d ordered urchin-like TiO2@Fe2O3 arrays [150]. Using these arrays Chai et al. reported a photocurrent density of 1.58 mA/cm2 at 1.23 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) [150]. This is a clear improvement compared to pristine TiO2.

A different approach is to use amorphous Fe2O3 with TiO2 and silicon (Si). With this method, Zhang et al. achieved a photocurrent density of 3.5 mA/cm2 at 1.23 V vs. RHE [151]. It is also possible to use TiO2 as the dopant on hematite. Fan Feng et al. decorated a hematite PEC with TiO2 at the grain boundaries [152] that increased the charge carrier density and improved the charge separation efficiency, resulting in a photocurrent density of 2.90 mA/cm2 at 1.23 V vs. RHE [152].

However, one could also use a simple TiO2/Fe2O3 heterojunction, which Deng et al. found improved the photocurrent density due to improved separation and transfer of photogenerated carriers [153].

A few studies are also reported on on metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) in cooperation with TiO2.

Yoon et al. coated TiO2 nanorods (NRs) with NH2–MIL-125(Ti) and achieved a photocurrent density of 1.62 mA/cm2 [154]. The high photocurrent can be explained by several factors: the large surface area and crystallinity of TiO2 NRs, which leads to effective light absorption and charge transport. Or the moderate bandgap of MIL(125)–NH2, the uniform and conformal coating of the MIL layer, and the efficient charge carrier separation and transportation through the type (II) band alignment of TiO2 and MIL(125)–NH2.

3.2. Non-Metal Dopants

Metal dopants could act as recombination centers for electrons and holes and thus lowering the overall efficiency of the photocatalyst [155]. Thus, a large number of research studies have been going on toward doping TiO2 with non-metal dopants, for example, Si, S, C, F, and N.

Yang Lu et al. doped TiO2 nanowires with earth-abundant Si and achieved an 18.2 times increase in the charge carrier density, which was better than in N and Ti (III) doped TiO2 [156]. The increase in visible light photocatalytic activity is due to the enhanced electron transport, because of higher charge-carrier density, longer electron lifetime, and larger diffusion coefficient in Si-doped TiO2 NWs [156]. High-quality graphene could be of use in water splitting as quantum dots on rutile TiO2 nanoflowers because they are highly luminescent and can absorb UV and visible light up to wavelengths of 700 nm [157]. Bellamkonda et al. found that multiwalled carbon nanotubes–graphene–TiO2 (CNT–GR–TiO2) could achieve a hydrogen production rate of 29 mmol/hg (19 mmol/hg for anatase TiO2) [158]. They also had an estimated solar energy conversion efficiency of 14.6% and a bandgap of 2.79 eV, which was due to the generation of Ti3+ and oxygen vacancies within the composite [158]. TiO2 absorbs UV light due to its inherent large bandgap, Qiongzhi Gao et al. [159] utilized this and doped TiO2 with hydrogenated F. The hydrogen-treated F atoms increased both UV and visible light absorption. When TiO2 is doped with sulfur, an abundant element, a bandgap of 2.15 eV can be expected [160]. N and lanthanum (La) co-doping of TiO2 does not reduce the bandgap, but the photocatalytic effect is seen to be enhanced due to an increase in surface nitrogen and oxygen vacancies [161].

3.3. Improved Production Methods

As discussed, although there are several options in order to dope TiO2 with metals and non-metals, the research community has devoted much energy to improving the characteristics of TiO2 photocatalysts through appropriate synthesis conditions. It is possible to achieve improved mechanical strength, enhanced composite stability, surface area, roughness, and fill factor for TiO2 by using branched multiphase TiO2 [162].

Treating TiO2 with Ar/NH3 during the fabrication process, which could improve the density of the charge carrier and broaden the photon absorption both in the UV and visible light regions [163]. An increase in density of states at the surface and a 2.5-fold increase in photocurrent density at 1.23 vs. RHE could be achieved by anodizing and annealing TiO2 during the fabrication process [164]. Ning Wei et al. showed that by controlling TiO2 core shells, it was possible to achieve a bandgap of 2.81 eV, and had an H2 evolution rate of 49.2 µmol/(h cm) [165].

Huali Huang et al. looked into the effect of annealing the atmosphere on the performance of TiO2 NR [46]. Oxygen, air, nitrogen, and argon were used as the different atmospheres. The same rutile phase was observed, but it resulted in different H2 activities. Samples annealed in argon showed the highest photocurrent density of 0.978 mA/cm2 at 1.23 V vs. RHE [46], an increase of 124.8% compared to the oxygen annealed samples. It was found that the density of oxygen vacancies in the samples increased with the decrease in oxygen in the annealing atmosphere [46]. The increase in oxygen vacancies enhances visible light absorption and increases the electron conductivity (inhibits recombination of the charge carriers) [46].

Aleksander et al. examined what would happen if the substrate, which TiO2 was fabricated on was changed [166]. The authors lowered the optical reflection by using black silicon, which in turn increased the light collection [166]. They also found that the addition of noble metals could induce SPR in the visible light region [166].

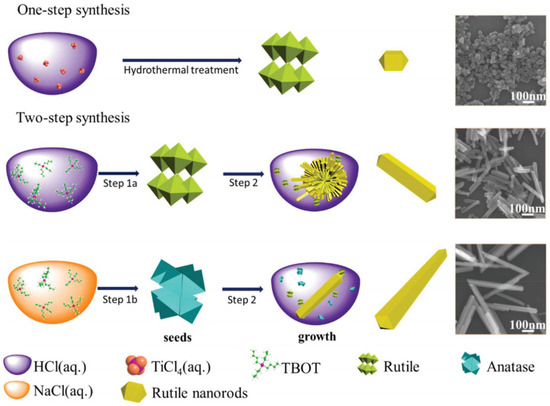

By combining improved production methods and doping/co-doping with metals/non-metals, TiO2 could be realized as an efficient photocatalyst. Fu et. al. showed that by controlling the HCl concentration during the synthesis process, it was possible to synthesize well-crystallized rutile TiO2 nanorods with special aspect ratios [167]. They proposed a process, as shown in Figure 9, for synthesizing rutile TiO2 with different aspect ratios. Rutile TiO2 nanorods with small aspect ratios were formed by placing titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4) in liquid hydrochloric acid (HCl) before undertaking hydrothermal treatment. The key factors were the presence of Cl− and H+ at high temperature and pressure. For the synthesis of nanorods with medium/large aspect ratios titanium butoxide (TBOT) was added dropwise to HCL (aq.)/NaCl (aq.) This created rutile/anatase crystal seeds, which were placed in HCl (aq.) for the final growth process. They concluded that with decreasing aspect ratios, the photocatalytic water splitting activity would increase for TiO2 nanorods [167].

Figure 9. Schematic illustration of the synthesis of rutile TiO2 with specific (small, medium, and large) aspect ratios. Reprinted with permission from [167]. Copyright 2018, with permission from RSC.