| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Elahe Alizadeh | + 4292 word(s) | 4292 | 2021-03-08 10:46:15 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | -44 word(s) | 4248 | 2021-03-24 02:23:07 | | |

Video Upload Options

Plasma medicine is a multidisciplinary field of research which is combining plasma physics and chemistry with biology and clinical medicine to launch a new cancer treatment modality. It mainly relies on utilizing low temperature plasmas in atmospheric pressure to generate and instill a cocktail of reactive species to selectively target malignant cells for inhibition the cell proliferation and tumor progression. Intracellular mechanisms of action and significant pathways behind the anticancer effects of plasma and selectivity toward cancer cells are comprehensively discussed. A thorough understanding of involved mechanisms helps investigators to explicate many disputes including optimal plasma parameters to control the reactive species combination and concentration, transferring plasma to the tumors located in deep, and determining the optimal dose of plasma for specific outcomes in clinical translation. As a novel strategy for cancer therapy in clinical trials, designing low temperature plasma sources which meet the technical requirements of medical devices still needs to improve in efficacy and safety.

1. Background and Motivation

Cancer is the second leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide after cardiovascular diseases [1]. Although, significant progresses have been achieved toward a better understanding of cancer therapy over the last few decades, nevertheless the World Health Organization estimated that this family of diseases was responsible for a likely 9.6 million deaths in 2018, which was about 1 in 6 deaths in the world [2]. Thus, cancer is still considered one of the deadliest threats to human health. Current conventional cancer treatments, comprising of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy, all aim to achieve a complete eradication of cancer cells without affecting non-malignant tissues. In surgery, complete surgical excision of tumor cells is challenged by microscopic tumor residues, consequently tumors can return if not fully removed. In radiation therapy (exploiting high-energy ionizing radiation), the necessity to protect healthy tissues surrounding a tumor is the major issue that extremely limits the therapeutic radiation dose. Despite of causing inevitably damages to normal tissues, radiation therapy still remains as an important modality for curing at least 50% of all cancer patients [3]. Similarly, in chemotherapy (utilizing cytotoxic drugs), chemotherapeutic agents point cells with the high basal level of proliferation and regeneration. Thus, both tumor cells and surrounding healthy cells with rapid proliferation (like hair, skin, bone marrow and epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract cells) are targeted by agents, consequently causing highly toxic effects related to the treatment [4][5]. In combined-modality therapy, cancer patients are treated with two or more of these modalities rather than just one to improve the chance of cure. For instance, chemoradiation therapy (CRT) is combining of radiation therapy and chemotherapy at the same time. Moreover, in concurrent chemoradiation therapy (CCRT), employing radiosensitizer or radioenhancers with platinum chemotherapeutic drugs together sensitizes the malignant cells to high-energy radiation [6] which is offering an alternative application of chemoradiation therapy [7][8]. Some emerging strategies including photothermal therapy (using photothermal agents activated by light to produce heat for tumor destruction), gene therapy and immune therapy have also shown reasonable potential in cancer treatment. However, they undergo various limitations like drug resistance, pathogenesis complications, cytotoxicity to healthy tissues, inadequate delivery methods to the tumor site, and high recurrence rates of some certain types of cancer. In general, the ideal alternatives and more effective therapies for cancer should be less-invasive treatments with strong cytotoxic effect on malignant cells and inferior side effects on healthy cells.

One of the most crucial causes of cancer initiation and progression is the formation of reactive species in biological systems. Interestingly, on the other hand, high doses of reactive species possess the capability to damage malignant cells. Therefore, utilizing external physical or chemical methods to produce and instill a high concentration of reactive species to the cells is a promising approach for inhibition the growth of cancer cells via several intracellular mechanisms. Low temperature plasma (LTP) is another new modality for cancer treatment relying on the generating a cocktail of reactive species in plasma to selectively target malignant cells for inhibition and treatment of cancer. Understanding of the anticancer mechanisms of plasma-based processes and LTP’s selectivity toward cancer cells still need to be investigated [9].

Plasma, called the forth state of the matter, fundamentally is an entirely or partially ionized gas consisting of biologically and chemically reactive species, including free electrons and radicals, as well as atoms, and molecules either in neutral or charged form. In addition to chemically reactive species, depending on plasma force, plasma produces physically active agents, i.e., electromagnetic fields leading to the emission of visible light, ultraviolet (UV) or vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) radiations, and propagating disturbances like shock waves and heating [10]. In the laboratory, plasmas are conveniently created by applying an electric field to the injected gas or vapor between two electrodes, typically pure helium, argon, neon or their mixtures with different percentages of oxygen or other compounds. The electric field accelerates electrons and initiates a cascade of collisional processes (excitation, ionization, and dissociation) that gives rise to a diverse range of chemical species. The numbers of positively charged ions and electrons in the discharge are generally equal except in plasma surfaces, where electric fields are strong. The amount of applied power, and the type and pressure of the processing gas determine the energy (thus the temperature) and the chemical combination of the cocktail of species. Proportionality of electrons and positive ions results in no relatively high electric charge at low pressures (like in fluorescent lamps) or at very high temperatures (like in stars and nuclear fusion reactors). At near-ambient temperatures or in low temperature plasma (so-called cold plasma, non-thermal plasma or non-equilibrium plasma), the gas temperature is slightly above room temperature and biologically tolerable (< 40 °C), while electron temperature is in order of a few thousands of °C [11][12]. Low temperature plasmas applied in atmospheric pressure are efficient sources of very high concentrations of reactive species. They contain reactive atomic and molecular species, including unstable, short lived or metastable excited atoms or ions and radicals. Moreover, they prominently contain reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydroxyl free radicals (OH) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) such as nitric oxide (NO) and nitrite (NO2−) [13][14].

The complex nature and exact mechanisms of interaction of atmospheric pressure LTP with biological systems has been intensively investigated [11][15][16][17][18][19]. Most of these studies have focused on the role of reactive species in cancer initiation and progression, as well as their antitumor effects in a variety of malignance, consequently indicating the capacity of LTP to induce highly significant lethal effects in cells and cancer treatment [20]. In 2004, based on some primary results, Stoffels et al. [21] introduced the basis for a novel interdisciplinary field of research later called plasma medicine: optimal applications of LTP and its therapeutic potential in medicine and biology [22][23]. Friedman and Keidar were among the pioneering researchers who developed LTP sources for medical applications and showed that cold plasma selectively kills cancer cells. Friedman et al. used cold plasma for cancer treatment and showed that high doses of plasma leads to necrosis death and low doses to initiate apoptotic death post treatment [24][25][26][27]. Over the next decade after these findings, numerous in vitro studies have performed and showed remarkable selective anticancer effects of non-thermal atmospheric pressure plasma on approximately 20 types of malignant cell lines; including lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, glioblastoma, prostate cancer, ovarian cancer, osteosarcoma, melanoma and breast cancer [28].

2. Mechanisms of Action of Plasma-Generated Species in Inhibition and Treatment of Cancer

Ionizing radiation, including gamma- and X-ray photons, electrons, alpha particles, and other heavy ions, is one of the most commonly types of radiation applied for cancer treatments. Absorption of high-energy ionizing radiation in cells and tissues induces excitation and ionization of water molecules, which are constituting 70−80% of the cell structure. Thus, majority (over 66%) of the radiation energy deposited in the cell is absorbed initially by water molecules [29]. This is leading to the immediate formation of free radicals such as hydroxyl radicals (OH•), hydrogen (H•), H2O2 and hydrated electrons, which can react with significant biomolecules like DNA [30]. Hydroxyl free radicals carry no charge, but have a strong affinity for electrons causing to remove hydrogen atoms from biomolecules. For instance, abstraction of deoxyribose hydrogen atoms from DNA initiates at least one pathway, which resulting in the production of a DNA strand scission [31][32][33][34]. Free radicals and electrons can also interact with other surrounding molecules like oxygen to generate the highly reactive secondary free radicals and ROS, particularly the superoxide anion radical (O2•−) [35]. Superoxide radical can respectively interact with nitric oxide (NO) to form different RNS like peroxynitrite (ONOO−), which produces cellular dysfunction by S-nitrosylating proteins. Biological mechanisms behind the effectiveness of ROS/RNS in cancer treatment with ionizing radiation have been extensively explored earlier in many studies [36]. High-energy radiation-induced ROS are generated in a very short span of time (shorter than 10−8 s) [30][37][38] in irradiated cells and indirectly induce damage in mitochondrial proteins, as well as both nuclear DNA (nDNA) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Ionizing radiation also stimulates an increase in the production of endogenous ROS by mitochondria in the irradiated cells, which potentially leads to mitochondrial dysfunction. The remains of damaged mitochondria could generate or leak more ROS inside the cell, although the damaged mitochondria are removed by mitophagy.

Here, it is important to briefly review the effect of high-energy ionizing radiation on cells, since LTP regulates some similar pathways to cell-killing effect as radiation does. Although besides the ROS produced during water radiolysis and ROS production by mitochondria, there are ROS/RNS generated inside the plasma jet which play multiple roles in signaling cascades and mediates apoptosis [39][35][40]. The OH radical is the major common physicochemical factor which is numerously produced in both plasma and radiation treatments. Under exposure of LTP, generated OH radicals in gaseous form are transferred to the medium. These radicals are the major mediator and responsible for DNA damage in cells [41]. Arjunan et al. [42] has outstandingly reviewed and discussed various plasma-generated ROS/RNS involved in DNA damage, characterized DNA damage and their associated cellular responses induced by atmospheric pressure plasma jet [43]. Interestingly, low levels of ROS/RNS play an important role in vital physiological processes to promote cell survival, proliferation and migration, while excessive ROS levels contribute to accumulating the oxidative stress and finally the initiation and execution of apoptosis [44][45]. Extensive research has shown that these cellular responses can be initiated by severe oxidative DNA damage [46][47][48]. On the other hand, there is an increasing number of studies verifying the important role of intracellular ROS levels in plasma treatment of cancer cells. Within the cell, plasma-derived ROS can oxidize proteins involved in metabolic pathways, proteasome activity and mitochondrial respiration [49]. In addition, plasma can cause double-strand DNA breaks [50][51] that if irreversible, can lead to cell death [52]. This section mainly focuses on the role of mitochondria in continuous endogenous production of ROS following exposure to radiation or LTP treatment and its relationship to the biological effects.

2.1. Production of Endogenous ROS without Plasma Exposure

Under normal conditions without exposure of cells to high-energy radiation, mitochondria, peroxisomes and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) mostly contribute to the production of endogenous ROS in cells. Mammalian mitochondria are highly dynamic primary intracellular organelles that have a crucial role in cell metabolism and variety of other additional functions in apoptosis, iron-sulfur (Fe-S) proteins cluster generation and regulating of intra-mitochondrial calcium concentration [53]. Each mitochondrion contains numerous copies of a circular mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) encoding 13 imported proteins required for electron transport chain (ETC) activity and respiration. All other mitochondrial proteins are nuclear-encoded and are synthesized on cytoplasmic ribosomes [54]. Commonly ETC, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondria are the cell’s principal source of energy. ETC is located on inner membranes of mitochondria and is essential for a number of vital processes including the generation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). The TCA cycle (also known as the Krebs cycle) is a three-stage process which occurs in the mitochondrial matrix for oxidation of carbohydrates, lipids, and amino acids. This chemical process produces required intermediates NADH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) and FADH2 (flavin adenine dinucleotide) which are electron-rich donors for entering the ETC on the mitochondrial inner membrane for ATP production. Mitochondria possess sensors for molecular oxygen and nutrient levels and contain a number of enzymes like mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2) to transform oxygen to superoxide or its derivative hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) radicals. These reactions occur in the ETC when electrons react with O2 as the final electron acceptor resulting in the generation of O2•− radicals, which is the primary ROS generated in mitochondria (Figure 1). O2•− radicals are converted by mitochondrial SOD2 into H2O2, which can be turned into OH• radical via the Fenton reaction [55]. Electron transfer is linked to the ejection of H+ out of the mitochondrial matrix into the inter-membrane space, creating a proton gradient that drives the production of ATP through oxidative phosphorylation. Thus, consequence of the energy production process is the generation of ROS byproducts. Later, H2O2 is converted to H2O and O2 by the action of catalase [56][57].

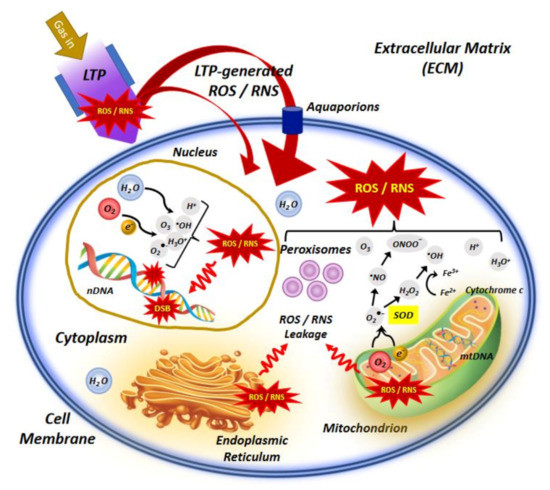

Figure 1. An illustrative representation of low temperature plasma (LTP) interaction with the cell, indicating the main molecular mechanisms involved in application of LTP in cancer treatment. In the extracellular matrix (ECM), LTP-generated species can penetrate the membrane of cells and organelles via lipid peroxidation, which leads to pore formation in the cell membrane and facilitates diffusion of reactive species into the cell. This effect may be enhanced in cancer cells due to reduced levels of cholesterol which is responsible for membrane stability and fluidity. Furthermore, extracellular ROS/RNS, specially H2O2 can pass aquaporins which are often increased in cancer cells and help transition of ROS/RNS via the cell membrane. Inside the cell, major intracellular sources of ROS/RNS are mitochondria, peroxisomes and endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Some species like O2•− and H2O2 may leak into the cell cytoplasm due to the disturbance of mitochondrial homeostasis. The imbalance of ROS/RNS in mitochondria can ultimately damages mitochondria causing mitochondrial dysfunction and trigger apoptosis. Increased levels of ROS/RNS by exposure to LTP can also destruct the antioxidant system and limit its protective effect against oxidative stress. Moreover, inside the nucleus, ROS/RNS may attack nearly all significant macromolecules like DNA and induce double strand breaks (DSBs) in nuclear DNA (nDNA).

As the main source of cellular ROS, mitochondria produce up to ninety percent of ROS in normal living cells. Although it rarely happens, O2•− and H2O2 may leak into the cell cytoplasm due to the disturbance of mitochondrial homeostasis because of the premature leakage of electrons mainly from defective ETC-related proteins complexes. These leaked ROS can react with important biomolecules, leading to the activation of oxidative stress responses to counteract the ROS. The imbalance of ROS in mitochondria can cause mitochondrial dysfunction which is the decisive factor in the pathways of cell apoptosis. Radiation causes further leakage of electrons from the ETC, excess ROS production and therefore results in further leakage of ROS by mitochondria, which will be more discussed in subsequent section.

Two other intracellular organelles contributing to the generation of ROS in normal cells are peroxisomes and ER. Peroxisomes are dynamic and metabolically active organelles that produce ROS in different metabolic pathways, including β- and α-oxidation of fatty acids, photorespiration, nucleic acid and polyamine catabolism and ureide metabolism. They also contain xanthine oxidase and the inducible form of NO synthase, which produce O2•− and NO•, respectively. The capacity to rapidly produce and scavenge H2O2 and O2•−, then increasing the formation of ONOO and OH• radicals (via Fenton reaction) helps peroxisomes for regulating dynamic changes in ROS levels [58]. ER is a continuous membrane system which constitutes more than half of the membranous content of mammalian cells and plays an important role in calcium storage, lipids metabolism, biosynthesis and transport of proteins and lipids. It is the place for folding and post-translational modifications of newly synthesized proteins. During protein folding process, formation of improperly paired disulfide bonds can lead to the accumulation of misfolded proteins aggregates and stimulation of unfolded protein response to facilitate correct protein folding. ER contains two enzymes, i.e., protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) and ER oxidoreductin 1 (ERO1), which are used for disulfide bond formation in the misfolded proteins, thereby folding them correctly. H2O2 is generated as a byproduct of oxidative protein folding process in ER. Glutathione is an essential antioxidant in ER which can reduce the formation of improperly paired disulfide bonds [59].

2.2. Production of Mitochondria-Dependent ROS after Plasma Treatment

Depending on the type of human cells, mitochondria occupy a fairly considerable fraction of cell volume (4–25%), which renders them a likely target of radiation traversal through the cell [57]. There are several copies of mtDNA in mitochondria, which code for ribosomal and transfer ribonucleic acid (rRNA and tRNA) and many other essential proteins for sustaining mitochondrial structure and functions [60][61][62]. Other required proteins for mitochondria are encoded by the nDNA. More importantly, as the powerhouse of the cells, mitochondria consume about 90% of the body’s oxygen through aerobic respiration and are the richest source of ROS. As shown in Figure 1, they divert about 1–5% of electrons from the respiratory chain to the formation of O2•− radicals by ubiquinone-dependent reduction [63]. Accordingly, exposure to any physical agents or carcinogenetic chemicals, like high-energy radiation in radiation therapy, pharmaceuticals in chemotherapy and LTP in plasma oncology could stimulates the domino effect on the ROS burst in the mitochondria. Various intracellular and extracellular signals induced by LTP-mediated ROS in mitochondria, increase their transmembrane potential and promoting the release of pro-apoptotic factors including cytochrome c. This process is regulated by the B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) protein family and ultimately leads to the activation of the caspase cascade [64]. Both in vitro and in vivo studies by Arndt et al. have shown that exposure of human melanoma cells to LTP initiated pro-apoptotic changes like Rad17 and tumor suppressor phospho-p53 phosphorylations, cytochrome c release and cleaved-caspase-3 activation, leading to improved wound healing [65][66].

Several observations have suggested that mtDNA could be a key molecule involved in plasma-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Overproduced ROS accumulated in mitochondria may target the mtDNA polymerase γ activity required for replication and repair of mtDNA, thereby resulting in reducing its repair capacity, damage and mutation of mtDNA [67]. They also may modify the assembly of large protein complexes and alter the proper expression of proteins which are required for critical mitochondrial and cellular functions [59]. The accumulation of damaged mtDNAs and mitochondrial proteins inhibits mitochondrial functions, including the maintenance of a stable mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP production. Subsequently, excess ROS accumulated in mitochondria in plasma-irradiated cells cause mitochondrial collapse and irreversible cell apoptosis, since mitochondria act as the major regulator of apoptosis (a type of programmed cell death) [68]. Mitochondrial dysfunction is associated to carcinogenesis, cancer progression and metastasis [69] and mitochondrial pathways such as ROS/RNS signaling or Ca2+ homeostasis which significantly contribute to the alteration of energy metabolism in cancer cells [70][71].

These dysfunctions are leading to an increase and continuous leakage of the mitochondrial ROS inside the whole cell and subsequently amplification of damages to nDNA and mitochondria. The presence of mitochondria with damaged mtDNA and oxidized proteins due to radiation-induced ROS production may provoke higher accumulation of oxidative and other types of damages in the cell [61][72][73]. However, dysfunctional mitochondria (those containing damaged mtDNA and oxidized proteins) can be eliminated by mitochondria-specific degradation systems called mitophagy. Mitophagy acts as a mitochondrial quality control measure and prevents excess mitochondrial-dependent ROS accumulation in cells after exposure to IR to repress the effect of leakage of ROS from the damaged mitochondria into the whole cell [74].

Other significant impact of radiation on function of mitochondria may take place during mitochondrial fission and fusion cycles. The mtDNA integrity is maintained during the fission and fusion cycles. Many studies have revealed that ionizing radiation stimulates mitochondrial fission in mammalian cells via an increase in Dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) [74][75]. Mitochondrial fission is primarily mediated by Drp1 as a main regulator in the division fission process and essential for the activation of mitophagy. Loss of Drp1 triggers genome instability and initiates DNA damage response by disrupting the mitochondrial fission and distribution [76]. Similar to Drp1, Parkin is another regulator of mitophagy, which its expression increases by radiation, triggering the activation of mitophagy in irradiated cells [77]. Moreover, Parkin-overexpressing cells seem to facilitate the removal of damaged mitochondria and to limit excess mitochondrial ROS production to avoid inducing apoptosis in radiosensitive cells [78].

There are several evidences suggesting that the anticancer effect of plasma radiation is predominantly caused by apoptosis-induction mediated by ROS/RNS primarily act in the extracellular matrix ECM [9]. Triggering apoptosis in plasma-irradiated cancer cells can be assumed from the ROS/RNS generated by LTP and added exogenously, even though some of these species have a very short life time and diffusion length due to their highly reactive nature and will not be able to reach the ECM, particularly in the bulk of a tumor. Changing the structure and function of proteins at the cell surface or in the ECM has been thoroughly investigated [9][79]. Here, we briefly remark that generated ROS/RNS in plasma can oxidize lipids in the cell membrane, reduce the membrane fluidity and produce pore formation. Thus, due to the permeability of the cell membrane, ROS/RNS penetrate the cell and reach to the intracellular compartment (Figure 1). Thus, cell contents may be released to the ECM, as unregulated digestion of cell components in necrotic cells [80]. These modifications at the cell surface can also activate signaling pathways to alter gene expression, cell growth and maintenance [81].

Furthermore, biological mechanisms behind the high selectivity of LTP to induce apoptosis in cancer cells can be elucidated here using plasma-generated ROS/RNS in cancerous and normal cells after LTP treatment [65]. Typically, normal tissues differ from tumor in the proportion of cells in each cell cycle phase at a given time, and in tumor tissues most cells are in the proliferative phase [42]. Plasma-generated ROS/RNS interfere with the signaling pathways used by cancerous cells to inhibit cell proliferation by inducing cell senescence. Thus, the proliferative signal turns into an apoptosis-inducing signal in cancer cells manipulated by LTP, while the signaling pathways manipulated by plasma do not exist in normal cells. Yan et al. demonstrated that LTP increased the percentage of apoptotic tumor cells by blocking the cell cycle at the G2/M checkpoint, and this effect was mediated by reducing intracellular cyclin B1 and cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdc2) and increasing p53 which is resulting in p53-dependant apoptosis [82][83][84]. However, the viability of non-tumor cells can also be altered with longer time of exposure to LTP [85].

Another differing parameter between cancer cells and normal cells that contribute to the high selectivity of LTP for inducing apoptosis in cancer cells is the lower levels of cholesterol in the membrane of cancer cells, which facilitate the diffusion of ROS inside the cells. Additionally, the increased number of aquaporins in the membrane of cancer cells lets easier transport of H2O2 into the cells [86][87]. When H2O2 is intact, it may enter the intracellular compartment through aquaporins, where it causes depletion of glutathione (GSH). The depletion of antioxidants like SOD2, GSH and glutathione peroxidases (GPx) via plasma exposure causes membrane attack by the superoxide and OH• radicals. Formation of OH• in the vicinity of the cell membrane causes lipid peroxidation of membrane and subsequent cell death by apoptosis. However, the extremely short lifetime and short diffusion length of OH• prevent harm on neighboring cells [88].

2.3. Oxidative Stress and Gene Expression

The level of intracellular ROS/RNS is carefully regulated by endogenous antioxidant enzymes such as SOD2, catalase, GSH and GPx, as well as some low-molecular-weight scavenging enzymes like uric acid, coenzyme Q and lipoic acid [89]. At low concentrations, ROS/RNS play an important role as regulatory mediators in various cellular functions and signaling processes. For instance, ROS are critical components of the antimicrobial repertoire of macrophages for bacterial destruction, or NO is involved in endothelial NO-mediated vasodilatation, which influences the function of circulating cells and underlying smooth muscles in a variety of cardiovascular disorders [90]. Whereas, at moderate or high concentrations, when ROS/RNS levels exceed the capacity of the redox balance control system, a phenomenon appears which is known as oxidative stress, referring to the state that ROS/RNS levels can be cytotoxic and lethal for cells. This suggests that the concentrations of reactive species regulate the shift from their advantageous to detrimental effects, yet the concentrations to which this shift happens and exact mechanisms are unclear [55].

Oxidative stress is involved in the development of various pathological conditions such as psoriasis, cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disorders, chronic ulcers, and conclusively tumor promotion and progression in cancer. Compared to normal cells, cancer cells display weaker antioxidant reactions. This property can facilitate selective attack of cancer cells by extracellular plasma-generated ROS/RNS, resulting in severe oxidative damage and cell death. Additionally, the bursts of ROS/RNS may affect directly or indirectly proteins and genes that participate in oxidative metabolism [91]. Perturbations in oxidative metabolism can lead to chromosomal instability in targeted and non-targeted cells as radiation-induced bystander effects [92]. Numerous in vitro studies have assessed the effects of LTP treatment on gene expression and epigenetics in several cell lines like melanoma and breast cancers [28][65][93][94][95]. Schmidt et al. observed that oxidative stress and alterations in redox state due to LTP treatment can modify the expression of nearly 3000 genes encoding structural proteins and inflammatory mediators, such as growth factors and cytokines. Moreover, plasma-activated medium treatment on melanoma cells caused changes in cellular morphology and mobility and colony formation, but was less effective on apoptosis and cell cycle progression [96][97][98].

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 7–30.

- World Health Organization. Available online: (accessed on 3 January 2021).

- Siva, S.; MacManus, M.P.; Martin, R.F.; Martin, O.A. Abscopal effects of radiation therapy: A clinical review for the radiobiologist. Cancer Lett. 2015, 356, 82–90.

- Lee, C.S.; Ryan, E.J.; Doherty, G.A. Gastro-intestinal toxicity of chemotherapeutics in colorectal cancer: The role of inflammation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 3751–3761.

- Trueb, R.M. Chemotherapy-induced hair loss. Skin Ther. Lett. 2010, 15, 5–7.

- Rezaee, M.; Alizadeh, E.; Cloutier, P.; Hunting, D.J.; Sanche, L. A single subexcitation-energy electron can induce a double-strand break in DNA modified by platinum chemotherapeutic drugs. Chem. Med. Chem. 2014, 9, 1145–1149.

- Seiwert, T.; Salama, J.; Vokes, E. The concurrent chemoradiation paradigm—General principles. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 4, 86–100.

- Charest, G.; Tippayamontri, T.; Shi, M.; Wehbe, M.; Anantha, M.; Bally, M.; Sanche, L. Concomitant chemoradiation therapy with gold nanoparticles and platinum drugs co-encapsulated in liposomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4848.

- Semmler, M.L.; Bekeschus, S.; Schäfer, M.; Bernhardt, T.; Fischer, T.; Witzke, K.; Seebauer, C.; Rebl, H.; Grambow, E.; Vollmar, B.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of the efficacy of cold atmospheric pressure plasma (CAP) in cancer treatment. Cancers 2020, 12, 269.

- Gümbel, D.; Bekeschus, S.; Gelbrich, N.; Napp, M.; Ekkernkamp, A.; Kramer, A.; Stope, M.B. Cold atmospheric plasma in the treatment of osteosarcoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2004.

- Saadati, F.; Mahdikia, H.; Abbaszadeh, H.; Khoramgah, M.S.; Shokri, B. Comparison of direct and indirect cold atmospheric-pressure plasma methods in the B16F10 melanoma cancer cells treatment. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7689.

- Laroussi, M.; Lu, X.; Keidar, M. Perspective: The physics, diagnostics, and applications of atmospheric pressure low temperature plasma sources used in plasma medicine. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 122, 020901.

- Lu, X.; Naidis, G.V.; Laroussi, M.; Reuter, S.; Graves, D.B.; Ostrikov, K. Reactive species in non-equilibrium atmospheric-pressure plasmas: Generation, transport, and biological effects. Phys. Rep. 2016, 630, 1–84.

- Babaeva, N.Y.; Naidis, G.V.; Tereshonok, D.V.; Son, E.E.; Vasiliev, M.M.; Petrov, O.F.; Fortov, V.E. Production of active species in argon microwave plasma torch. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 464004.

- Schlegel, J.; Köritzer, J.; Boxhammer, V. Plasma in cancer treatment. Clin. Plasma Med. 2013, 1, 2–7.

- Dobrynin, D.; Fridman, G.; Friedman, G.; Fridman, A. Physical and biological mechanisms of direct plasma interaction with living tissue. New J. Phys. 2009, 11, 115020.

- Laroussi, M. Nonthermal decontamination of biological media by atmospheric-pressure plasmas: Review, analysis, and prospects. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2002, 30, 1409–1415.

- Sakudo, A.; Misawa, T.; Shimizu, N.; Imanishi, Y. N2 gas plasma inactivates influenza virus mediated by oxidative stress. Front. Biosci. 2014, 6, 69–79.

- Weltmann, K.D.; von Woedtke, T. Plasma medicine—Current state of research and medical application. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 2017, 59, 014031.

- Chizoba Ekezie, F.G.; Sun, D.W.; Cheng, J.H. A review on recent advances in cold plasma technology for the food industry: Current applications and future trends. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 46–58.

- Stoffels, E.; Sladek, R.E.J.; Kieft, I.E. Gas plasma effects on living cells. Phys. Scr. 2004, T107, 79–82.

- Azzariti, A.; Iacobazzi, R.M.; Di Fonte, R.; Porcelli, L.; Gristina, R.; Favia, P.; Fracassi, F.; Trizio, I.; Silvestris, N.; Guida, G.; et al. Plasma-activated medium triggers cell death and the presentation of immune activating danger signals in melanoma and pancreatic cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4099.

- Bruggeman, P.J.; Kushner, M.J.; Locke, B.R.; Gardeniers, J.G.E.; Graham, W.G.; Graves, D.B.; Hofman-Caris, R.C.H.M.; Maric, D.; Reid, J.P.; Ceriani, E.; et al. Plasma-liquid interactions: A review and roadmap. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2016, 25, 053002.

- Fridman, G.; Shereshevsky, A.; Jost, M.M.; Brooks, A.D.; Fridman, A.; Gutsol, A.; Vasilets, V.; Friedman, G. Floating electrode dielectric barrier discharge plasma in air promoting apoptotic behavior in melanoma skin cancer cell lines. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2007, 27, 163–176.

- Fridman, G.; Peddinghaus, M.; Ayan, H.; Fridman, A.; Balasubramanian, M.; Gutsol, A.; Brooks, A.; Friedman, G. Blood coagulation and living tissue sterilization by floating-electrode dielectric barrier discharge in air. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process 2006, 26, 425–442.

- Fridman, G.; Friedman, G.; Gutsol, A.; Shekhter, A.B.; Vasilets, V.N.; Fridman, A. Applied plasma medicine. Plasma Process. Polym. 2008, 5, 503–533.

- Keidar, M.; Walk, R.; Shashurin, A.; Srinivasan, P.; Sandler, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Ravi, R.; Guerrero-Preston, R.; Trink, B. Cold plasma selectivity and the possibility of a paradigm shift in cancer therapy. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 105, 1295–1301.

- Gay-Mimbrera, J. Clinical and biological principles of cold atmospheric plasma application in skin cancer. Advances in therapy 2016, 33, 894–909.

- Alizadeh, E.; Sanche, L. Precursors of solvated electrons in radiobiological physics and chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 5578–5602.

- Alizadeh, E.; Orlando, T.M.; Sanche, L. Biomolecular damage induced by ionizing radiation: The direct and indirect effects of low-energy electrons on DNA. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2015, 66, 379–398.

- Lehnert, S. Biomolecular Action of Ionizing Radiation, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2008.

- Alizadeh, E.; Sanche, L. Induction of strand breaks in DNA by low energy electrons and soft X-Rays under nitrous oxide atmosphere. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2012, 81, 33–39.

- Riley, P.A. Free radicals in biology: Oxidative stress and the effects of ionizing radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1994, 65, 27–33.

- Nuszkiewicz, J.; Woźniak, A.; Szewczyk-Golec, K. Ionizing radiation as a source of oxidative stress—The protective role of Melatonin and Vitamin D. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5804.

- Alizadeh, E.; Sanz, A.G.; Garcia, G.; Sanche, L. Radiation damage to DNA: The indirect effect of low energy electrons. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 820–825.

- Mitra, S.; Nguyen, L.N.; Akter, M.; Park, G.; Choi, E.H.; Kaushik, N.K. Impact of ROS generated by chemical, physical, and plasma techniques on cancer attenuation. Cancers 2019, 11, 1030.

- Alizadeh, E.; Sanche, L. Low-energy-electron interactions with DNA: Approaching cellular conditions with atmospheric experiments. Eur. Phys. J. D 2014, 68, 1–13.

- Alizadeh, E.; Ptasińska, S.; Sanche, L. Transient anions in radiobiology and radiotherapy: From gaseous biomolecules to condensed organic and biomolecular solids. In Radiation Effects in Materials; Monteiro, W.A., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2016; pp. 179–230.

- Pasqual-Melo, G.; Sagwal, S.K.; Freund, E.; Gandhirajan, R.K.; Frey, B.; von Woedtke, T.; Gaipl, U.; Bekeschus, S. Combination of gas plasma and radiotherapy has immunostimulatory potential and additive toxicity in murine melanoma cells in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1379.

- Perillo, B.; Di Donato, M.; Pezone, A.; Di Zazzo, E.; Giovannelli, P.; Galasso, G.; Castoria, G.; Migliaccio, A. ROS in cancer therapy: The bright side of the moon. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 192–203.

- Ji, W.O.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, G.H.; Kim, E.H. Quantitation of the ROS production in plasma and radiation treatments of biotargets. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19837.

- Arjunan, K.P.; Sharma, V.K.; Ptasińska, P. Effects of atmospheric pressure plasmas on isolated and cellular DNA—A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 2971–3016.

- Han, X.; Kapaldo, J.; Lin, Y.; Sharon Stack, M.; Alizadeh, E.; Ptasińska, S. Large-scale image analysis for investigating spatio-temporal changes in cell DNA damage caused by nitrogen atmospheric pressure plasma jets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. Plasma Biol. 2020, 21, 4127.

- Simon, H.U.; Haj-Yehia, A.; Levi-Schaffer, F. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis 2000, 5, 415–418.

- Circu, M.L.; Aw, T.Y. Reactive oxygen species, cellular redox systems, and apoptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 48, 749–762.

- Barzilai, A.; Yamamoto, K.I. DNA damage responses to oxidative stress. DNA Repair 2004, 3, 1109–1115.

- Saito, K.; Asai, T.; Fujiwara, K.; Sahara, J.; Koguchi, H.; Fukuda, N.; Suzuki-Karasaki, M.; Soma, M.; Suzuki-Karasaki, Y. Tumor-selective mitochondrial network collapse induced by atmospheric gas plasma-activated medium. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 19910–19927.

- Gómez-Serrano, M.; Camafeita, E.; Loureiro, M.; Peral, B. Mitoproteomics: Tackling mitochondrial dysfunction in human disease. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, 1435934.

- Dezest, M.; Chavatte, L.; Bourdens, M.; Quinton, D.; Camus, M.; Garrigues, L.; Descargues, P.; Arbault, S.; Burlet-Schiltz, O.; Casteilla, L.; et al. Mechanistic insights into the impact of cold atmospheric pressure plasma on human epithelial cell lines. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41163.

- Han, X.; Klas, M.; Liu, Y.; Stack, M.S.; Ptasińska, S. DNA damage in oral cancer cells induced by nitrogen atmospheric pressure plasma jets. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 233703.

- Hirst, A.M.; Simms, M.S.; Mann, V.M.; Maitland, N.J.; O’Connell, D.; Frame, F.M. Low-temperature plasma treatment induces DNA damage leading to necrotic cell death in primary prostate epithelial cells. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 1536–1545.

- Dickey, J.S.; Redon, C.E.; Nakamura, A.J.; Baird, B.J.; Sedelnikova, O.A.; Bonner, W.M. H2AX: Functional roles and potential applications. Chromosoma 2009, 118, 683–692.

- Dasgupta, A.; Wu, D.; Tian, L.; Xiong, P.Y.; Dunham-Snary, K.J.; Chen, K.H.; Alizadeh, E.; Motamed, M.; Potus, F.; Hindmarch, C.C.T.; et al. Mitochondria in the pulmonary vasculature in health and disease: Oxygen-sensing, metabolism, and dynamics. Compr. Physiol. 2020, 10, 713–765.

- Scheffler, I.E. Mitochondria, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Liss: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008.

- Di Meo, S.; Reed, T.T.; Venditti, P.; Victor, V.M. Role of ROS and RNS sources in physiological and pathological conditions. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 2016, 1245049.

- Lee, H.L.; Chen, C.L.; Yeh, S.T.; Zweier, J.L.; Chen, Y.R. Biphasic modulation of the mitochondrial electron transport chain in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012, 302, H1410–H1422.

- Kalogeris, T.; Bao, Y.; Korthuis, R.J. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species: A double edged sword in ischemia/reperfusion vs preconditioning. Redox Biol. 2014, 2, 702–714.

- Sandalio, L.M.; Rodríguez-Serrano, M.; Romero-Puertas, M.C.; del Río, L.A. Role of peroxisomes as a source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling molecules. Subcell Biochem. 2013, 69, 231–255.

- Berg, J.M.; Tymoczko, J.L.; Stryer, L. Biochemistry, 6th ed.; W. H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

- Alizadeh, E.; Sanche, L. The role of humidity and oxygen level on damage to DNA induced by soft X-rays and low-energy electrons. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 22445–22453.

- Leach, J.K.; Van Tuyle, G.; Lin, P.S.; Schmidt-Ullrich, R.; Mikkelsen, R.B. Ionizing radiation-induced, mitochondria-dependent generation of reactive oxygen/nitrogen. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 3894–3901.

- Wu, D.; Dasgupta, A.; Read, A.D.; Bentley, R.E.T.; Motamed, M.; Chen, K.H.; Al-Qazazi, R.; Mewburn, J.D.; Dunham-Snary, K.J.; Alizadeh, E.; et al. Oxygen sensing, mitochondrial biology and experimental therapeutics for pulmonary hypertension and cancer. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021.

- Cadenas, E.; Davies, K.J. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 29, 222–230.

- Zirnheld, J.L.; Zucker, S.N.; DiSanto, T.M.; Berezney, R.; Etemadi, K. Nonthermal plasma needle: Development and targeting of melanoma cells. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2010, 38, 948–952.

- Arndt, S.; Wacker, E.; Li, Y.F.; Shimizu, T.; Thomas, H.M.; Morfill, G.E.; Karrer, S.; Zimmermann, J.L.; Bosserhoff, A.K. Cold atmospheric plasma, a new strategy to induce senescence in melanoma cells. Exp. Dermatol. 2013, 22, 284–289.

- Wang, Q.; Goldstein, M.; Alexander, P.; Wakeman, T.P.; Sun, T.; Feng, J.; Lou, Z.; Kastan, M.B.; Wang, X.F. Rad17 recruits the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 complex to regulate the cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 862–877.

- Azzam, E.I.; Jay-Gerin, J.P.; Pain, D. Ionizing radiation-induced metabolic oxidative stress and prolonged cell injury. Cancer Lett. 2012, 327, 48–60.

- Crooks, D.R.; Maio, N.; Lang, M.; Ricketts, C.J.; Vocke, C.D.; Gurram, S.; Turan, S.; Kim, Y.Y.; Cawthon, G.M.; Sohelian, F.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA alterations underlie an irreversible shift to aerobic glycolysis in fumarate hydratase–deficient renal cancer. Sci. Signal. 2021, 14, eabc4436.

- Potter, M.; Newport, E.; Morten, K.J. The Warburg effect: 80 years on. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2016, 44, 1499–1505.

- Kang, S.W.; Lee, S.; Lee, E.K. ROS and energy metabolism in cancer cells: Alliance for fast growth. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2015, 38, 338–345.

- Uzhachenko, R.; Shanker, A.; Yarbrough, W.G.; Ivanova, A.V. Mitochondria, calcium, and tumor suppressor Fus1: At the crossroad of cancer, inflammation, and autoimmunity. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 20754–20772.

- Li, B.Y.; Sun, J.; Wei, H.; Cheng, Y.-Z.; Xue, L.; Cheng, Z.-H.; Wam, J.-W.; Wang, A.-Q.; Hei, T.K.; Tong, J. Radon-induced reduced apoptosis in human bronchial epithelial cells with knockdown of mitochondria DNA. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2012, 75, 1111–1119.

- Dayal, D.; Martin, S.M.; Owens, K.M.; Aykin-Burns, N.; Zhu, Y.; Boominathan, A.; Pain, D.; Limoli, C.L.; Goswami, P.C.; Domann, F.E.; et al. Mitochondrial complex II dysfunction can contribute significantly to genomic instability after exposure to ionizing radiation. Radiat. Res. 2009, 172, 737–745.

- Hu, L.; Wang, H.; Huang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J. Crosstalk between autophagy and intracellular radiation response. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 49, 2217–2226.

- Twig, G.; Elorza, A.; Molina, A.J.; Mohamed, H.; Wikstrom, J.D.; Walzer, G.; Stiles, L.; Haigh, S.E.; Katz, S.; Las, G.; et al. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. EMBO J. 2008, 27, 433–446.

- Hu, C.; Huang, Y.; Li, L. Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission plays critical roles in physiological and pathological progresses in mammals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 144.

- Shimura, T.; Kobayashi, J.; Komatsu, K.; Kunugita, N. Severe mitochondrial damage associated with low-dose radiation sensitivity in ATM- and NBS1-deficient cells. Cell Cycle 2016, 15, 1099–1107.

- Kawamura, K.; Qi, F.; Kobayashi, J. Potential relationship between the biological effects of low-dose irradiation and mitochondrial ROS production. J. Radiat. Res. 2018, 59, ii91–ii97.

- Eisenhauer, P.; Chernets, N.; Song, Y.; Dobrynin, D.; Pleshko, N.; Steinbeck, M.J.; Freeman, T.A. Chemical modification of extracellular matrix by cold atmospheric plasma-generated reactive species affects chondrogenesis and bone formation. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2016, 10, 772–782.

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Gueydan, C.; Han, J. Plasma membrane changes during programmed cell deaths. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 9–21.

- Poltavets, V.; Kochetkova, M.; Pitson, S.M.; Samuel, M.S. The role of the extracellular matrix and its molecular and cellular regulators in cancer cell plasticity. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 431.

- Tuhvatulin, A.I.; Sysolyatina, E.V.; Scheblyakov, D.V.; Logunov, D.Y.; Vasiliev, M.M.; Yurova, M.A.; Danilova, M.A.; Petrov, O.F.; Naroditsky, B.S.; Morfill, G.E.; et al. Non-thermal plasma causes p53-dependent apoptosis in human colon carcinoma cells. Acta Nat. 2012, 4, 82–87.

- Yan, X.; Xiong, Z.; Zou, F.; Zhao, S.; Lu, X.; Yang, G.; He, G.; Ostrikov, K. Plasma-induced death of HepG2 cancer cells: Intracellular effects of reactive species. Plasma Process. Polym. 2012, 9, 59–66.

- Yan, X.; Zou, F.; Zhao, S.; Lu, X. On the mechanism of plasma inducing cell apoptosis. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2010, 38, 2451–2457.

- Kim, K.C.; Piao, M.J.; Madduma Hewage, S.R.K.; Han, X.; Kang, K.A.; Jo, J.O.; Mok, Y.S.; Shin, J.H.; Park, Y.; Yoo, S.J.; et al. Non-thermal dielectric-barrier discharge plasma damages human keratinocytes by inducing oxidative stress. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 37, 29–38.

- Yan, D.; Talbot, A.; Nourmohammadi, N.; Sherman, J.H.; Cheng, X.; Keidar, M. Toward understanding the selective anticancer capacity of cold atmospheric plasma—A model based on aquaporins. Biointerphases 2015, 10, 040801.

- Van der Paal, J.; Neyts, E.C.; Verlackt, C.C.W.; Bogaerts, A. Effect of lipid peroxidation on membrane permeability of cancer and normal cells subjected to oxidative stress. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 489–498.

- McCord, J.M. Superoxide dismutase, lipid peroxidation, and bell-shaped dose response curves. Dose Respons. 2008, 6, 223–238.

- Poljsak, B.; Šuput, D.; Milisav, I. Achieving the balance between ROS and antioxidants: When to use the synthetic antioxidants. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2013, 2013, 956792.

- Vallance, P.; Hingorani, A. Endothelial nitric oxide in humans in health and disease. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 1999, 80, 291–303.

- Mikkelsen, R.B.; Wardman, P. Biological chemistry of reactive oxygen and nitrogen and radiation- induced signal transduction mechanisms. Oncogene 2003, 22, 5734–5754.

- Lorimore, S.A.; Mukherjee, D.; Robinson, J.I.; Chrystal, J.A.; Wright, E.G. Long-lived inflammatory signaling in irradiated bone marrow is genome dependent. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 6485–6491.

- Park, S.B.; Kim, B.; Bae, H.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.; Choi, E.H.; Kim, S.J. Differential epigenetic effects of atmospheric cold plasma on MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129931.

- Arndt, S.; Unger, P.; Wacker, E.; Shimizu, T.; Heinlin, J.; Li, Y.F.; Thomas, H.M.; Morfill, G.E.; Zimmermann, J.L.; Bosserhoff, A.K.; et al. Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) changes gene expression of key molecules of the wound healing machinery and improves wound healing in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79325.

- Zhong, S.Y.; Dong, Y.Y.; Liu, D.X.; Xu, D.H.; Xiao, S.X.; Chen, H.L.; Kong, M.G. Surface air plasma induced cell death and cytokines release of human keratinocytes in the context of psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2016, 174, 542–552.

- Schmidt, A.; Bekeschus, S.; von Woedtke, T.; Hasse, S. Cell migration and adhesion of a human melanoma cell line is decreased by cold plasma treatment. Clin. Plasma Med. 2015, 3, 24–31.

- Schmidt, A.; von Woedtke, T.; Bekeschus, S. Periodic exposure of keratinocytes to cold physical plasma—An in vitro model for redox-related diseases of the skin. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 2016, 9816072.

- von Woedtke, T.; Schmidt, A.; Bekeschus, S.; Wende, K.; Weltmann, K.D. Plasma Medicine: A field of applied Redox biology. In Vivo 2019, 33, 1011–1026.