| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yoshinobu Eishi | + 1070 word(s) | 1070 | 2021-03-17 07:13:10 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 1070 | 2021-03-19 11:25:01 | | |

Video Upload Options

Sarcoidosis may have more than a single causative agent, including infectious and non-infectious agents. Among the potential infectious causes of sarcoidosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Propionibacterium acnes are the most likely microorganisms.

1. Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a systemic inflammatory disease that is characterized by the formation of noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas at the sites of disease activity in multiple organs, including the lungs and lymph nodes [1]. Despite numerous studies using molecular and immunologic approaches, the cause of sarcoidosis remains uncertain. Sarcoidosis may have more than a single causative agent, including infectious and non-infectious agents [2]. Even if a specific microorganism is involved, the infectious agent does not need to cause sarcoidosis in every host or experimental animal according to Koch’s postulates for establishing causation of an infectious disease [3].

Among the potential infectious agents, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Propionibacterium acnes (formerly known as Corynebacterium parvum and currently referred to as Cutibacterium acnes) [4] are the most likely causative microorganisms of sarcoidosis. Which of the two infectious agents is more likely to contribute to the pathogenesis among sarcoidosis patients worldwide, however, remains uncertain.

2. Causative Agents of Granuloma Formation

Granulomas serve as a protective mechanism to confine poorly degradable extrinsic agents [5]. Foreign body granulomas are formed by agents with weak antigenicity (e.g., surgical sutures), whereas epithelioid cell granulomas are formed by agents with strong antigenicity that can induce an active Th1 immune response [6]. In infectious diseases, microorganisms usually act as both foreign bodies and antigens that induce immunologic responses [7].

Histologically, granulomas start to form as small aggregations of lymphocytes and macrophages around poorly degraded antigens. At the beginning of granuloma formation, macrophages change to epithelioid cells and organize into cell clusters (immature granuloma). As the granuloma progresses, a ball-like cluster of epithelioid cells develops, which is occasionally accompanied by the fusion of macrophages into giant cells (mature granuloma). In granulomas caused by infectious or non-infectious agents, the causative agent is present or has been present in the granulomas [5]. To identify a certain agent as the cause of Th1 granuloma formation, evidence of its presence in the granulomas as well as antigenic hypersensitivity in the patient must be established. This concept of infectious granuloma pathogenesis is the same as that in cases of non-infectious granulomas, such as berylliosis, and must be considered when searching for unknown causative agents of sarcoidosis.

While histopathologic investigations are useful for detecting and locating the causative agents in granulomas, the extrinsic agents or antigens in the granulomas are usually degraded or abolished by the granuloma cells, which have a greater intracellular digestive ability than conventional macrophages [8][9]. Therefore, the causative agent in granulomas may no longer be present, and may only be observed in a few, if any, tissue sections of the granulomas. Because of the degradation process in the granuloma, the causative agent is more likely to be identified in immature granulomas with many inflammatory cells than in mature granulomas with only a few lymphocytes. When a microorganism is detected in granulomas, it is highly suspected as the cause, but even when no microorganism is identified, a microbial etiology cannot be excluded. In infectious granulomas, microbial antigens detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC) are more likely to be degraded or abolished compared with microbial DNA detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or in situ hybridization methods.

3. Microorganisms Detected in Sarcoid Tissues

Due to the common features of sarcoidosis and tuberculosis, a mycobacterial cause of sarcoidosis has been suggested since the first description of the disease over a century ago. Although mycobacteria have not been found in sarcoid tissues by conventional histologic and culture techniques [10], a mycobacterial etiology was hypothesized after successful PCR detection of M. tuberculosis DNA in sarcoid tissues [11], including granulomas and tissues outside the granulomas. On the basis of a meta-analysis [12] of 31 studies using qualitative PCR published from 1980 to 2006, the odds ratio (OR) for identifying mycobacterial DNA, including M. tuberculosis complex (MTC) and nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), in sarcoidosis versus control samples was calculated to be 9.67; mycobacterial DNA was detected in 231 (26%) of 874 sarcoidosis samples (MTC: 187, NTM: 43, and both: 1) and in 17 (3%) of 600 control samples (MTC: 13, NTM: 2, and unknown: 2). The detection frequencies in sarcoid tissues were greater than 50% in seven studies, 20% to 50% in eight studies, less than 20% in nine studies, and 0% in seven studies.

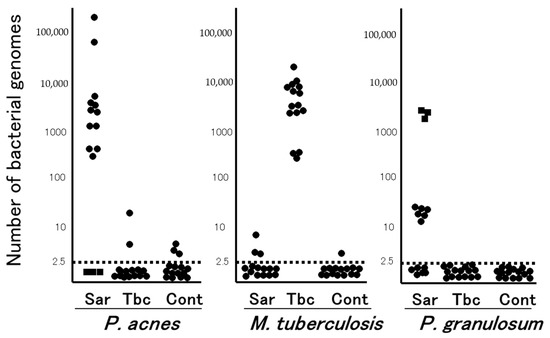

In the late 1970s, the Japanese government supported extensive efforts to isolate microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi from sarcoid tissues, which unexpectedly led to the isolation of only P. acnes and no other microorganism, including mycobacteria, from sarcoid tissues [13]; P. acnes was isolated from 78% of 40 sarcoidosis and 21% of 180 control lymph nodes [14]. Quantitative PCR led to the detection of many P. acnes genomes in 80% of sarcoidosis samples and only a few P. acnes genomes in 17% of non-sarcoidosis samples (Figure 1). Many M. tuberculosis genomes were detected in all tuberculosis samples and a few were detected in 13% of non-tuberculosis samples [15]. Consequently, an international collaborative study on lymph node samples was performed in Japan, Italy, Germany, and England using quantitative real-time PCR [16]; either P. acnes or P. granulosum was detected in all but two sarcoidosis samples. M. tuberculosis was detected in 0% to 9% of sarcoidosis samples and 65% to 100% of tuberculosis samples. In sarcoid lymph node samples from each country, the observations of propionibacterial genomes far outnumbered those of M. tuberculosis genomes.

Figure 1. Quantitative PCR for mycobacterial and propionibacterial DNA in sarcoid lymph nodes. Lymph node samples from each of the 15 patients with sarcoidosis (Sar), tuberculosis (Tbc), and gastric cancer (Cont) were used in this study. The horizontal dotted lines show the detection threshold and samples with results below this line are considered negative. Samples without P. acnes detected (as indicated by dotted squares) all contained many P. granulosum (reproduced from Ishige et al. [15] with permission from the Lancet, London).

The results of a recent meta-analysis of 58 studies involving more than 6000 patients in several countries evaluating all types of infectious agents proposed to be associated with sarcoidosis suggested an etiologic link with P. acnes (OR: 18.8, 95%; CI: 12.6, 28.1) and mycobacteria (OR: 6.8, 95%; CI: 3.7, 12.4) [17]. Other infectious agents such as Borrelia (OR: 4.8), HHV-8 (OR: 1.5) as well as Rickettsia helvetica, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Epstein–Barr virus, and retrovirus, although suggested by previous investigation, were not associated with sarcoidosis.

Bacterial DNA was detected in lymph nodes from 11 (37%) of 30 sarcoidosis patients (P. acnes: 6, NTM: 3, and others: 2) and 2 (7%) of 30 control patients (P. acnes: 1 and NTM: 1) using 16S-rRNA gene sequencing [18]. Similarly, high-throughput 16S-rRNA gene sequencing revealed a significantly higher relative abundance of P. acnes in lymph node samples obtained from a sarcoidosis group (0.16%) than in those obtained from control (0%) and tuberculosis (0%) cohorts, while the relative abundance of mycobacterium did not differ between sarcoidosis (0.06%) and control (0.05%) samples [19].

References

- Valeyre, D.; Prasse, A.; Nunes, H.; Uzunhan, Y.; Brillet, P.-Y.; Müller-Quernheim, J. Sarcoidosis. Lancet 2014, 383, 1155–1167.

- Beijer, E.; Veltkamp, M.; Meek, B.; Moller, D.R. Etiology and Immunopathogenesis of Sarcoidosis: Novel Insights. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 38, 404–416.

- Casadevall, A.; Pirofski, L.A. Host-pathogen interactions: Redefining the basic concepts of virulence and pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 3703–3713.

- Alexeyev, O.A.; Dekio, I.; Layton, A.M.; Li, H.; Hughes, H.; Morris, T.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Patrick, S. Why we continue to use the name Propionibacterium acnes. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 179, 1227.

- Sell, S. Granulomatous Reactions. In Immunology Immunopathology and Immunity; Elsevier Science Publishing Company, Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1987; pp. 529–544.

- Pagán, A.J.; Ramakrishnan, L. The Formation and Function of Granulomas. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 36, 639–665.

- Zumla, A.; James, D.G. Granulomatous infections: Etiology and classification. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1996, 23, 146–158.

- Carr, I. Sarcoid macrophage giant cells. Ultrastructure and lysozyme content. Virchows Arch. B Cell Pathol. Incl. Mol. Pathol. 1980, 32, 147–155.

- Okabe, T.; Suzuki, A.; Ishikawa, H.; Yotsumoto, H.; Ohsawa, N. Cells originating from sarcoid granulomas in vitro. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1981, 124, 608–612.

- Wilsher, M.L.; Menzies, R.E.; Croxson, M.C. Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in tissues affected by sarcoidosis. Thorax 1998, 53, 871–874.

- Saboor, S.A.; Johnson, N.M.; McFadden, J. Detection of mycobacterial DNA in sarcoidosis and tuberculosis with polymerase chain reaction. Lancet 1992, 339, 1012–1015.

- Gupta, D.; Agarwal, R.; Aggarwal, A.N.; Jindal, S.K. Molecular evidence for the role of mycobacteria in sarcoidosis: A meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2007, 30, 508–516.

- Homma, J.Y.; Abe, C.; Chosa, H.; Ueda, K.; Saegusa, J.; Nakayama, M.; Homma, H.; Washizaki, M.; Okano, H. Bacteriological investigation on biopsy specimens from patients with sarcoidosis. Jpn. J. Exp. Med. 1978, 48, 251–255.

- Abe, C.; Iwai, K.; Mikami, R.; Hosoda, Y. Frequent isolation of Propionibacterium acnes from sarcoidosis lymph nodes. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Mikrobiol. Hyg. A 1984, 256, 541–547.

- Ishige, I.; Usui, Y.; Takemura, T.; Eishi, Y. Quantitative PCR of mycobacterial and propionibacterial DNA in lymph nodes of Japanese patients with sarcoidosis. Lancet 1999, 354, 120–123.

- Eishi, Y.; Suga, M.; Ishige, I.; Kobayashi, D.; Yamada, T.; Takemura, T.; Takizawa, T.; Koike, M.; Kudoh, S.; Costabel, U.; et al. Quantitative analysis of mycobacterial and propionibacterial DNA in lymph nodes of Japanese and European patients with sarcoidosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 198–204.

- Esteves, T.; Aparicio, G.; Garcia-Patos, V. Is there any association between Sarcoidosis and infectious agents?: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2016, 16, 165.

- Robinson, L.A.; Smith, P.; Sengupta, D.J.; Prentice, J.L.; Sandin, R.L. Molecular analysis of sarcoidosis lymph nodes for microorganisms: A case-control study with clinical correlates. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e004065.

- Zhao, M.-M.; Du, S.-S.; Li, Q.-H.; Chen, T.; Qiu, H.; Wu, Q.; Chen, S.-S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.; et al. High throughput 16SrRNA gene sequencing reveals the correlation between Propionibacterium acnes and sarcoidosis. Respir. Res. 2017, 18, 28.