| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ioana Roxana Bordea | + 3110 word(s) | 3110 | 2020-11-05 07:37:48 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | + 1 word(s) | 3111 | 2021-03-19 10:03:42 | | | | |

| 3 | Bruce Ren | + 1 word(s) | 3111 | 2021-03-19 10:04:26 | | |

Video Upload Options

In the context of the SARS-CoV-2 (Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) pandemic, the medical system has been subjected to many changes. Face-to-face treatments have been suspended for a period of time. After the lockdown, dentists have to be aware of the modalities to protect themselves and their patients in order not to get infected. Dental practitioners are potentially exposed to a high degree of contamination with SARS-CoV-2 while performing dental procedures that produce aerosols. It should also be noted that the airways, namely the oral cavity and nostrils, are the access pathways for SARS-CoV-2. In order to protect themselves and their patients, they have to use full personal protective equipment. Relevant data regarding this pandemic are under evaluation and are still under test.

1. Introduction

In December 2019, an outbreak of pneumonia appeared in Wuhan City. Wuhan is an important international trading centre in central China. This pathology was concluded to be generated by a novel Coronavirus (nCoV-2019). Since then, the virus infection has spread throughout the world, it has been declared a pandemic by WHO on 12 March 2020 [1][2][3]. It seems that the first COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) cases were connected to a large fish and living animal market in this large metropolis. It was thought that the path of direct transmission came from a food market. Since then, person-to-person transmission has been found be one of the main spreading mechanisms of COVID-19 [1][2][3].

After the identification of the initial cases, the pandemic hit almost all the nations in the world. Now, there are more than 1,113,307 deaths worldwide due to the coronavirus pandemic. The updated data of Johns Hopkins University identified 1,113,307 deaths. On the other hand, 39,964,414 contagions are global. COVID-19 has spread to 189 countries and territories and there are approximately 39,964,414 confirmed cases (as of 19 October 2020) [4].

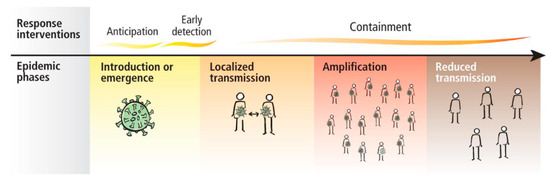

The WHO (World Health Organization) presented the guidance for case management of COVID-19 in health facility and community Interim on 19 March 2020 [3]. The response interventions proposed by the WHO are presented in Figure 1.

Because this pandemic emerged in our lives and has produced a lot of changes, dental professionals have to introduce new strategies to perform dental treatments in order to reduce the risk of cross infection. A study performed by a team of Jordanian dentists showed that dental practitioners have very little information regarding the measures they have to take in order to protect themselves and their patients [5]. In his study, Ing showed that 4% of deaths were dentists because of the lack of protection equipment [6].

In this article, we made a synthesis about the way in which SARS-CoV-2 spreads, how to diagnose a novel corona virus infection, what the possible treatments are, and which protective personal equipment we can use to stop its spreading.

2. Epidemiology

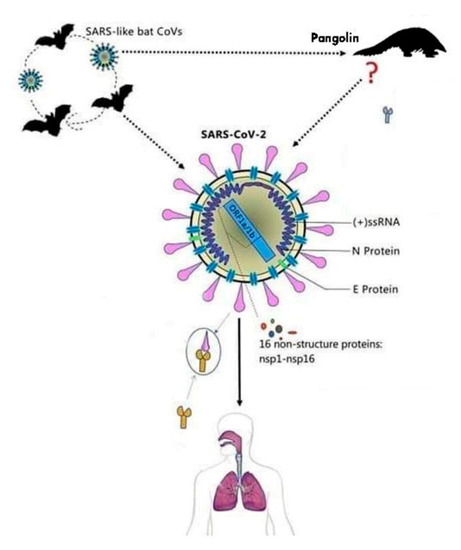

The first name given to this virus was 2019-nCoV, after a short period of time the name of the virus was changed due to the similarity with the SARS virus into SARS-CoV-2 [7]. The virus comes from the family of Coronaviridae and is made of single stranded RNA viruses [7]. This virus can be secluded from animal species and can determine cross infection, passing the barriers of certain species and infecting animals and humans. The virus has a cover that is composed of glycoproteins that look similar to a solar crown, as shown in Figure 2 [7].

In the literature, there are four genera of Coronaviruses. Two of the genera, γ-CoV and δ-CoV, determine changes in birds, while the other two genera, α-CoV and β-CoV, contaminate mostly mammals and also humans, by determining changes in different systems of the organism like the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and central nervous systems [7][8][9][10][11]. The new virus that determined infections in Wuhan belongs to the β-CoV family of viruses that includes the SARS-CoV (Severe Acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus) and MERS-CoV (Middle East respiratory syndrome), two viruses that are known for the infections they caused several years ago [8][9][10][11][12][13][14].

The nucleotide sequence similarity between SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV is of about 80% and approximately 50% between SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV. This could explain the reason why this novel virus is less deadly than the other two. Hence, its routes of transmission can spread the SARS-CoV-2 faster than the other two viruses [15][16][17][18][19][20]. It has been suggested that the natural host of SARS-CoV-2 may be the Rhinolophus affine bat, due to the similarities in the RNA (ribonucleic acid) sequence of the coronavirus found in the bat (96.2%) and SARS-CoV-2, and the intermediate host is the pangolin, with a genome sequence similarity of 99% between SARS-CoV-2 and the coronavirus found in these species [15][16][17][18][19][20].

The bat is now considered to be the first source of the virus and the initial hypothesis of the infection from the pangolin that has been considered to be an intermediate host has been discarded [17]. Tang et al. suggested that the genomic sequence between the pangolin virus and the human one is not 99%, but lower (84%) than that the bat one (96%) [22].

Scientists are now taking into consideration the fact that the virus evolved and is infecting humans that were asymptomatic for three months, and in the same manner it increases the infectious capacity and reduces lethality [21].

This type of virus has the same structure as the common coronavirus, possessing the “spike protein” in the exterior structure of the envelope of the virion, and besides this, in its structure we can find proteins like nucleo, poly, and membrane proteins that include RNA polymerase, papain-like protease, helicase, 3-chymotrypsin-like protease, accessory proteins, and glycoprotein. The S protein from coronavirus can bind with the receptors of the host to encourage viral entry into target cells. Although there are four amino acid variations of S protein between SARS-CoV-2 and SARSCoV, the first can also bind with the human angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the same host receptor for the SARSCoV. SARS-CoV-2 cannot bind with cells without the presence of ACE2. The recombinant ACE2-Ig antibody, SARSCoV-specific human monoclonal antibody, and the serum from a convalescent SARS-CoV-infected patient can neutralize SARS-CoV-2, and thus confirms ACE2 as the host receptor for SARS-CoV-2. Due to the high affinity between ACE2 and SARS-CoV-2 S protein, it has been suggested that the population with a higher expression of ACE2 might be more susceptible to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) [17][18][25][26][27].

There is a great number of articles stating the fact that SARS-CoV-2 uses the S protein complex and the ACE2 receptor to entry the host cell. This information is used in different ways and domains, and above all in therapeutic treatment modality, diagnostic purposes, and infection transmission and prevention [28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45].

Zhou et al. indicated that the angiotensin-converting enzyme II (ACE2) is likely the cell receptor of SARS-CoV-2, which is also the receptor for SARS-CoV. Moreover, it has been proven that SARS-CoV-2 does not use other coronavirus receptors such as aminopeptidase N and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 [44]. Xu et al. showed that the S-protein of the SARS-CoV-2 supports a strong interaction with human ACE2. Those findings suggest that the ACE2 plays an important role in cellular entry of the SARS-CoV-2, thus, ACE2-expressing cells may act as target cells for susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Moreover, this research has shown that the ACE2 could be expressed in the oral cavity, which was highly enriched in the oral epithelial cells, especially at a higher level in the tongue than in the buccal and gingival tissues. These findings indicate that the oral mucosa can express a potential high-risk route of SARS-CoV-2 infection transmission [45]. This fact underlines the importance of dentists and dental healthcare workers to wear all the protective measures that are indicated to prevent infection [18].

The connection between the host and the virus is encouraged by the S glycoprotein that integrates the receptors of the host cells to produce the viral infection of the cells. This glycoprotein is part of the class 1 viral fusion proteins and it has more than 1300 amino acids [46].

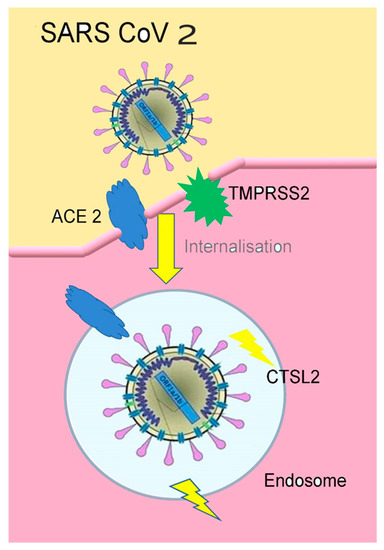

The SARS CoV 2 can also bind a specific enzyme in the human body that is represented by the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE 2), in order to bind the virus to the cells which need this enzyme [47]. The way the entire process takes place is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The connection of SARS-CoV2 to ACE2(figure inspired by https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/receptors-for-sars-cov-2-present-in-wide-variety-of-human-cells-67496 [48], and drawn by Giovanna Dipalma).

TMPRSS2(transmembrane protease serine 2) is an enzyme used by the SARS-CoV2 for S protein priming. CTSL2 (Cathepsin L2) is a gene, proteins encoded in this gene are members of the peptidase C1 family. For the SARS-CoV2 virus entering the human cells, Spike (S) protein needs to be cleaved by the cellular enzyme furin [49][50].

Furin is an enzyme, encoded by the FURIN gene, in the cells, belonging to hydrolases, splits proteins (inactive precursors) and transforms them into an active biological state (mature proteins) [44][45].

The S protein allows the virus to transfer the genome into the cell which leads to viral replication. In order to become active, the S protein must be cleaved by proteases. The S protein has two functional domains S1 and S2. S1 is implicated in the initial stage of viral entry, using its receptor binding domain to link to the receptors of the target cell and S2 acts in the second stage, fusing the cell and the viral membrane containing amino acid sequences necessary to continue the infiltration process [50][51][52][53][54].

In the corona virus family, the S protein has the largest variable amino acid sequence. In this virus the furin site is located between S1 and S2 subunits not unlike the pattern found in high-pathogenic influenza viruses, but not in other members of the Beta coronavirus genus [50][51][52].

Several patches of the RBD (receptor binding domain) are similar in SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, an overall amino acid sequence identity of 76.47%. Because of the five important interface amino acid residues, four of these are different in SARS-CoV-2, and its S protein has a significantly higher binding affinity to human ACE2 than SARS-CoV S protein. Regardless of this, the two viruses shared an almost identical 3-D structure of the RBD which demonstrates similar Van der Waals electrostatic properties [50][51][52][53][54].

As treatment options, the effective antibodies against SARS-CoV’s spike S protein did not bind to the SARS-CoV-2 S protein. So, a vaccine sounds more tempting, but in order to create a live attenuated vaccine we must limit the replicative capabilities of the virus. In order to achieve this, we could remove the furin activation sequence which is essential for cell–virus fusion, thus allowing it to replicate. By doing so, the immune system can create antibodies in order to neutralise the virus and protect the body from further infections [50][51][52][53][54][55].

Another option would be to isolate antibodies from patients who have recovered from COVID-19 by using the novel S protein structure and mapping its structure in order to mass produce them [50].

In 2012 a new corona virus MERS-CoV (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus) was discovered resulting in a disease that manifests itself as severe respiratory disease with renal failure. The fatality rate was up to 38%. The place of emergencies was the Middle East, specifically countries where dromedary camels were identified as species harbouring the virus. Another outbreak was seen in 2015 in South Korea where the final tally was 36 people killed out of 186 confirmed cases. The SARS-CoV outbreak in southeast China had a worldwide tally of 774 killed from 8096 infected with a fatality rate of 9.6% [56].

3. Viral Load-Inflammation

The world virus comes from Latin and means “poison”. Viruses are small microorganisms whose size varies from 0.2–0.3 μm to 1 μm. They need a host cell for living and reproducing (bacterial, vegetal, or animal). They have a very simple structure with an external cover of glycol proteins and lipids, called an envelope or pericapsid, in which there is a protective coat called capsid surrounding the virus genome. In the literature, there are DNA and RNA viruses, double stranded (DNA virus or dsRNA virus) or single (ssDNA virus or ssRNA) stranded. For the latter there is the “polarity” (consisting in process coding the virus) which can be positive or negative, namely ssDNA, ssRNA-, ssDNA+, or ssRNA+ (coronavirus) [57][58]. The cell replication (cytoplasmic or nuclear) is guided by the genome. The genome of the virus enters the host cell, and in few hours the formation of thousands of viral particles is performed, and they spread in the external environment. The replication of the RNA virus occurs easily with errors, as there is no RNA polymerase during the transcription. The high number of viruses as well as the error high frequency during the transcription are the main factors explaining the fast capacity to evolve proper of the SARS-CoV-2. Resistance to therapy is justified by the RNA mutation, even if it is very small, and allows the virus to avoid the attack of the immune system, continuing to change in terms of response in order to adapt to the constant changes of the genome [57][58].

Corona viruses are classified according to their own nature, structure, genome, and replication. The main feature of viruses is the infection of a special type of cell on which surface there are receptors which are similar to the binding. When binding with the host cell membrane is performed through those receptors, the virus penetrates the cell with its own genome, DNA or RNA. In this way. replication and multiplication of the virus starts. After the virus replication, the host cell usually dies. freeing new microorganisms in the surrounding environment where they can keep on infecting a new host cell having completed their lifecycle [59][60].

The Furin is considerably present in the lung tissue, in the intestine and the liver, this would make those organs as potential target of the 2019-nCoV infection. In dental field, Furin expression has been also revealed by the epithelium of the human tongue and in significant quantities in the squamous cell carcinoma. Researchers have shown a high availability of ACE2 receptors as well as the presence of Furin. Therefore, the tongue has a high risk of coronavirus infection and the SCC increases the risk in case of coronavirus exposure. The cleavage site on the spike similar to Furin plays an important role in spreading the 2019-nCoV virus [61][62][63][64][65][66][67].

At the moment there are some researches in which this site is eliminated, by observing effects or blocking the action of Furin, as issued on Nature [16]. This explains the strategic possibilities which we can sum up in this way:

- 1.

-

Molecules inhibiting Spike-ACE2.

- 2.

-

Anti-Serin protease molecules.

- 3.

-

Molecule inhibiting the HR1 domain (sub. S2).

- 4.

The activation of TMPRSS2 (Trans Membrane Protease, Serine 2) is fundamental as SARS-CoV-2 infects the lung cells, SARS-CoV-2 can use the TMPRSS2 to trigger the S protein. Some studies highlight that the TMPRSS2 is an important element of the host cell as it is essential for spreading a great number of viruses causing potentially significant infections, as the influenza A and coronavirus. Important data show that the TMPRSS2 is not necessary for the development and homeostasis and so it is potentially and sensible pharmacological target able to inactivate the infection. It is important to underline that the serine protease inhibitor, camostat mesylate, blocks the TMPRSS2 activity. This treatment, or something similar with likely increased antiviral activity (Yamamoto et al., 2016), could be used for treating patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Further studies suggest that the activation mediated by Furin on the S1 / S2 site within the infected cells could activate the subsequent access depending on the TMPRSS2 within the target cells [69][70][71][72][73].

An analysis on the real proteolytic elaboration of the protease on the S protein, and on its cleavage in S1 and S2 through detection with the antigenic system, underlined the existence of a band corresponding to the subunit S2 and protein S of the host cells infected by the virus of the vesicular stomatitis (VSV) containing SARS-2-S [61][62][63][64][65][66][67].

Knowing the action of the SARS-CoV-2 may allow to produce targeted drugs and vaccines against the COVID-19, a new treatment modality investigated is the one using PRP (platelet rich plasma), PRF (platelet rich fibrin), and CGF (concentrated growth factors) [74][75][76][77][78][79][80].

In 2011, a study on macaques infected by coronavirus with severe lung infections has been taken into consideration as the saliva droplets were source of infection [81].

It has been confirmed that the epithelial cells of the salivary glands covering the salivary ducts had high ACE2 expression (Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2), and therefore the first target cells have been revealed together with the first production source of virus [46][49][50][82][83][84][85].

The ACE2 expression in human organs has been analyzed by considering data collected by the portal Genotype-Tissue Expression. It is noted that the ACE2 expression in minor salivary glands was higher than the ones found in lungs. As a result, salivary glands are targets for SARS-CoV [82].

Another confirmation derives from the fact that the SARS-CoV-2 may be recorded in the saliva before lungs lesions appear. This explains the presence of asymptomatic infections. Therefore, it is possible to state that the salivary gland is not only the first access site for the SARS-CoV-2, but also one of the main reproduction sources, as it makes saliva highly infective and infecting [81][82][83]. Indeed, the high presence of corona virus SARS-CoV-2 in saliva of COVID19 patients reaches 91.7%, and from their saliva samples it is also possible to easily cultivate the virus in vivo [83][84][85][86][87][88][89].

There is a study analyzing the virus SARS-CoV-2 resistance to the internal surfaces and to the sun light. This study proved that the UV-C light (absent to the natural light) inactivates coronaviruses and that the UVB levels found in sun light may really inactivate the SARS-CoV-2 on surfaces, especially the dry virus on stainless steel specimens. This research provided the first evidence that sun light may quickly inactivate the SARS-CoV-2 on surfaces. Data suggest that the natural sun light may be also effective as a disinfectant for contaminated non-porous materials [90]. Researchers have also revealed that the simulated sun light is quickly able to inactivate the corona virus SARS-CoV-2 on specimens performed on stainless steel. The results of this study highlighted that 90% of the infecting virus was inactivated in a period of time consisting of 6.8 min in the saliva solution. The sun light necessary for those tests is similar to the summer solstice, in a not cloudy day. Researchers stated that the inactivation has been tested when the sun light levels were also lower [90][91].

References

- WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19–13 May 2020. Available online: (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Operational Considerations for Case Management of COVID-19 in Health Facility and Community. Available online: (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- COVID-19 Map. Available online: (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Khader, Y.; Al Nsour, M.; Al-Batayneh, O.B.; Saadeh, R.; Bashier, H.; Alfaqih, M.; Al-Azzam, S.; AlShurman, B.A. Dentists’ Awareness, Perception, and Attitude Regarding COVID-19 and Infection Control: Cross-Sectional Study Among Jordanian Dentists. Jmir. Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e18798.

- Ing, E.; Xu, A.Q.; Salimi, A.; Torun, N. Physician Deaths from Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19). Occup. Med. 2020, 70, 370–374.

- Valencia, D.N. Brief Review on COVID-19: The 2020 Pandemic Caused by SARS-CoV-2. Cureus 2020, 12.

- Yin, Y.; Wunderink, R.G. MERS, SARS and other coronaviruses as causes of pneumonia. Respirology 2018, 23, 130–137.

- Ong, S.W.X.; Tan, Y.K.; Chia, P.Y.; Lee, T.H.; Ng, O.T.; Wong, M.S.Y.; Marimuthu, K. Air, Surface Environmental, and Personal Protective Equipment Contamination by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) From a Symptomatic Patient. JAMA 2020.

- Young, B.E.; Ong, S.W.X.; Kalimuddin, S.; Low, J.G.; Tan, S.Y.; Loh, J.; Ng, O.-T.; Marimuthu, K.; Ang, L.W.; Mak, T.M.; et al. Epidemiologic Features and Clinical Course of Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore. JAMA 2020, 323, 1488–1494.

- Corman, V.M.; Landt, O.; Kaiser, M.; Molenkamp, R.; Meijer, A.; Chu, D.K.; Bleicker, T.; Brünink, S.; Schneider, J.; Schmidt, M.L.; et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25.

- Perlman, S.; Netland, J. Coronaviruses post-SARS: Update on replication and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 439–450.

- Cascella, M.; Rajnik, M.; Cuomo, A.; Dulebohn, S.C.; Di Napoli, R. Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19); StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020.

- Ye, Z.-W.; Yuan, S.; Yuen, K.-S.; Fung, S.-Y.; Chan, C.-P.; Jin, D.-Y. Zoonotic origins of human coronaviruses. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1686–1697.

- Dietz, L.; Horve, P.F.; Coil, D.A.; Fretz, M.; Eisen, J.A.; Wymelenberg, K.V.D. 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic: Built Environment Considerations to Reduce Transmission. mSystems 2020, 5.

- Andersen, K.G.; Rambaut, A.; Lipkin, W.I.; Holmes, E.C.; Garry, R.F. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 450–452.

- Peng, X.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Cheng, L.; Zhou, X.; Ren, B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 12, 9.

- Xu, H.; Zhong, L.; Deng, J.; Peng, J.; Dan, H.; Zeng, X.; Li, T.; Chen, Q. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 12, 8.

- Chan, J.F.-W.; To, K.K.-W.; Tse, H.; Jin, D.-Y.; Yuen, K.-Y. Interspecies transmission and emergence of novel viruses: Lessons from bats and birds. Trends Microbiol. 2013, 21, 544–555.

- Wahba, L.; Jain, N.; Fire, A.Z.; Shoura, M.J.; Artiles, K.L.; McCoy, M.J.; Jeong, D.E. Identification of a pangolin niche for a 2019-nCoV-like coronavirus through an extensive meta-metagenomic search. bioRxiv 2020.

- Chiara, G.D. SARS-CoV-2: Il Mistero di un Virus Perfetto. Available online: (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Tang, X.; Wu, C.; Li, X.; Song, Y.; Yao, X.; Wu, X.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Qian, Z.; et al. On the origin and continuing evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 1012–1023.

- Korber, B.; Fischer, W.M.; Gnanakaran, S.; Yoon, H.; Theiler, J.; Abfalterer, W.; Foley, B.; Giorgi, E.E.; Bhattacharya, T.; Parker, M.D.; et al. Spike mutation pipeline reveals the emergence of a more transmissible form of SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv 2020.

- Zhang, T.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Z. Probable Pangolin Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Associated with the COVID-19 Outbreak. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 1346–1351.

- Yuen, K.-S.; Ye, Z.-W.; Fung, S.-Y.; Chan, C.-P.; Jin, D.-Y. SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: The most important research questions. Cell. Biosci. 2020, 10, 1–5.

- Cui, J.; Li, F.; Shi, Z.-L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 181–192.

- Wang, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Li, J.-Y.; Zhou, Z.-J.; Liao, C.-H.; Ge, X.-Y. A Unique Protease Cleavage Site Predicted in the Spike Protein of the Novel Pneumonia Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Potentially Related to Viral Transmissibility. Virol. Sin. 2020, 1–3.

- Fung, S.-Y.; Yuen, K.-S.; Ye, Z.-W.; Chan, C.-P.; Jin, D.-Y. A tug-of-war between severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 and host antiviral defence: Lessons from other pathogenic viruses. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 558–570.

- Liu, Y.; Ning, Z.; Chen, Y.; Guo, M.; Liu, Y.; Gali, N.K.; Sun, L.; Duan, Y.; Cai, J.; Westerdahl, D.; et al. Aerodynamic Characteristics and RNA Concentration of SARS-CoV-2 Aerosol in Wuhan Hospitals during COVID-19 Outbreak. bioRxiv 2020.

- Gudbjartsson, D.F.; Helgason, A.; Jonsson, H.; Magnusson, O.T.; Melsted, P.; Norddahl, G.L.; Saemundsdottir, J.; Sigurdsson, A.; Sulem, P.; Agustsdottir, A.B.; et al. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the Icelandic Population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020.

- Chan, J.F.-W.; Yip, C.C.-Y.; To, K.K.-W.; Tang, T.H.-C.; Wong, S.C.-Y.; Leung, K.-H.; Fung, A.Y.-F.; Ng, A.C.-K.; Zou, Z.; Tsoi, H.-W.; et al. Improved Molecular Diagnosis of COVID-19 by the Novel, Highly Sensitive and Specific COVID-19-RdRp/Hel Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR Assay Validated In Vitro and with Clinical Specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58.

- Yip, C.C.-Y.; Ho, C.-C.; Chan, J.F.-W.; To, K.K.-W.; Chan, H.S.-Y.; Wong, S.C.-Y.; Leung, K.-H.; Fung, A.Y.-F.; Ng, A.C.-K.; Zou, Z.; et al. Development of a Novel, Genome Subtraction-Derived, SARS-CoV-2-Specific COVID-19-nsp2 Real-Time RT-PCR Assay and Its Evaluation Using Clinical Specimens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2574.

- Yan, Y.; Shin, W.I.; Pang, Y.X.; Meng, Y.; Lai, J.; You, C.; Zhao, H.; Lester, E.; Wu, T.; Pang, C.H. The First 75 Days of Novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Outbreak: Recent Advances, Prevention, and Treatment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2323.

- Li, M.; Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, C.; Li, X. The SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 expression of maternal-fetal interface and fetal organs by single-cell transcriptome study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15.

- Yang, Y.; Peng, F.; Wang, R.; Yang, M.; Guan, K.; Jiang, T.; Xu, G.; Sun, J.; Chang, C. Corrigendum to The deadly coronaviruses: The 2003 SARS pandemic and the 2020 novel coronavirus epidemic in China. J. Autoimmun. 2020.

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Niu, S.; Song, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, G.; Qiao, C.; Hu, Y.; Yuen, K.-Y.; et al. Structural and Functional Basis of SARS-CoV-2 Entry by Using Human ACE2. Cell 2020, 181, 894–904.

- El-Aziz, T.M.A.; Stockand, J.D. Recent progress and challenges in drug development against COVID-19 coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)—An update on the status. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020.

- Khailany, R.A.; Safdar, M.; Ozaslan, M. Genomic characterization of a novel SARS-CoV-2. Gene Rep. 2020, 19, 100682.

- Abduljalil, J.M.; Abduljalil, B.M. Epidemiology, genome, and clinical features of the pandemic SARS-CoV-2: A recent view. New Microbes New Infect. 2020, 35, 100672.

- Xie, X.; Muruato, A.; Lokugamage, K.G.; Narayanan, K.; Zhang, X.; Zou, J.; Liu, J.; Schindewolf, C.; Bopp, N.E.; Aguilar, P.V.; et al. An Infectious cDNA Clone of SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 841–848.

- Qiang, X.-L.; Xu, P.; Fang, G.; Liu, W.-B.; Kou, Z. Using the spike protein feature to predict infection risk and monitor the evolutionary dynamic of coronavirus. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 33.

- Xia, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Xu, W.; Lan, Q.; Feng, S.; Qi, F.; Bao, L.; Du, L.; Liu, S.; et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (previously 2019-nCoV) infection by a highly potent pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting its spike protein that harbors a high capacity to mediate membrane fusion. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 343–355.

- Yan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 2020, 367, 1444–1448.

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273.

- Xu, X.; Chen, P.; Wang, J.; Feng, J.; Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Zhong, W.; Hao, P. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 457–460.

- Song, W.; Gui, M.; Wang, X.; Xiang, Y. Cryo-EM structure of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein in complex with its host cell receptor ACE2. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007236.

- Magrone, T.; Magrone, M.; Jirillo, E. Focus on Receptors for Coronaviruses with Special Reference to Angiotensin-converting Enzyme 2 as a Potential Drug Target—A Perspective. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2020.

- Receptors for SARS-CoV-2 Present in Wide Variety of Human Cells. Available online: (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.-H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.

- Lan, J.; Ge, J.; Yu, J.; Shan, S.; Zhou, H.; Fan, S.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2020, 581, 215–220.

- Li, F.; Li, W.; Farzan, M.; Harrison, S.C. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science 2005, 309, 1864–1868.

- Lu, R.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Niu, P.; Yang, B.; Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Song, H.; Huang, B.; Zhu, N.; et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet 2020, 395, 565–574.

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506.

- Activation Sequence of COVID-19 S Protein Cleaved by Furin Protease. Available online: (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Characterization of Spike Glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on Virus Entry and its Immune Cross-Reactivity with SARS-CoV. Available online: (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Wong, G.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, B.; Bi, Y.; Gao, G.F. MERS, SARS, and Ebola: The Role of Super-Spreaders in Infectious Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 18, 398–401.

- Betacoronavirus ViralZone Page. Available online: (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Sigrist, C.J.; Bridge, A.; Le Mercier, P. A potential role for integrins in host cell entry by SARS-CoV-2. Antivir. Res. 2020, 177, 104759.

- Coronaviridae ~ ViralZone Page. Available online: (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Sanjuán, R.; Nebot, M.R.; Chirico, N.; Mansky, L.M.; Belshaw, R. Viral Mutation Rates. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 9733–9748.

- Izaguirre, G. The Proteolytic Regulation of Virus Cell Entry by Furin and Other Proprotein Convertases. Viruses 2019, 11, 837.

- Dohan Ehrenfest, D.M.; Del Corso, M.; Inchingolo, F.; Charrier, J.-B. Selecting a relevant in vitro cell model for testing and comparing the effects of a Choukroun’s platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) membrane and a platelet-rich plasma (PRP) gel: Tricks and traps. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2010, 110, 409–411.

- Coutard, B.; Valle, C.; de Lamballerie, X.; Canard, B.; Seidah, N.G.; Decroly, E. The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in CoV of the same clade. Antivir. Res. 2020, 176, 104742.

- Hasan, A.; Paray, B.A.; Hussain, A.; Qadir, F.A.; Attar, F.; Aziz, F.M.; Sharifi, M.; Derakhshankhah, H.; Rasti, B.; Mehrabi, M.; et al. A review on the cleavage priming of the spike protein on coronavirus by angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 and furin. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–9.

- Bassi, D.E.; Zhang, J.; Renner, C.; Klein-Szanto, A.J. Targeting Proprotein Convertases in Furin-Rich Lung Cancer Cells Results in Decreased In vitro and In vivo Growth. Mol. Carcinog. 2017, 56, 1182–1188.

- López de Cicco, R.; Watson, J.C.; Bassi, D.E.; Litwin, S.; Klein-Szanto, A.J. Simultaneous expression of furin and vascular endothelial growth factor in human oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma progression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 4480–4488.

- Martins-Filho, P.R.; Gois-Santos, V.T.; Tavares, C.S.S.; de Melo, E.G.M.; do Nascimento, E.M., Jr.; Santos, V.S. Recommendations for a safety dental care management during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Rev. Panam. Salud. Publica 2017, 1–7.

- Mohammadzadeh Rostami, F.; Nasr Esfahani, B.N.; Ahadi, A.M.; Shalibeik, S. A Review of Novel Coronavirus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Iran. J. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 14, 154–161.

- Upendran, A.; Geiger, Z. Dental Infection Control; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020.

- Iwata-Yoshikawa, N.; Okamura, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Hasegawa, H.; Takeda, M.; Nagata, N. TMPRSS2 Contributes to Virus Spread and Immunopathology in the Airways of Murine Models after Coronavirus Infection. J. Virol. 2019, 93.

- Shirato, K.; Kawase, M.; Matsuyama, S. Wild-type human coronaviruses prefer cell-surface TMPRSS2 to endosomal cathepsins for cell entry. Virology 2018, 517, 9–15.

- Fan, Y.; Zhao, K.; Shi, Z.-L.; Zhou, P. Bat Coronaviruses in China. Viruses 2019, 11, 210.

- Meng, T.; Cao, H.; Zhang, H.; Kang, Z.; Xu, D.; Gong, H.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Cui, X.; Xu, H.; et al. The insert sequence in SARS-CoV-2 enhances spike protein cleavage by TMPRSS. BioRxiv 2020.

- Inchingolo, F.; Martelli, F.S.; Gargiulo Isacco, C.; Borsani, E.; Cantore, S.; Corcioli, F.; Boddi, A.; Nguyễn, K.C.D.; De Vito, D.; Aityan, S.K.; et al. Chronic Periodontitis and Immunity, Towards the Implementation of a Personalized Medicine: A Translational Research on Gene Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) Linked to Chronic Oral Dysbiosis in 96 Caucasian Patients. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 115.

- Dohan Ehrenfest, D.M.; Bielecki, T.; Mishra, A.; Borzini, P.; Inchingolo, F.; Sammartino, G.; Rasmusson, L.; Everts, P.A. In search of a consensus terminology in the field of platelet concentrates for surgical use: Platelet-rich plasma (PRP), platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), fibrin gel polymerization and leukocytes. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2012, 13, 1131–1137.

- Dohan Ehrenfest, D.M.; Bielecki, T.; Jimbo, R.; Barbé, G.; Del Corso, M.; Inchingolo, F.; Sammartino, G. Do the fibrin architecture and leukocyte content influence the growth factor release of platelet concentrates? An evidence-based answer comparing a pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) gel and a leukocyte—And platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF). Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2012, 13, 1145–1152.

- Dohan Ehrenfest, D.M.; Del Corso, M.; Inchingolo, F.; Sammartino, G.; Charrier, J.-B. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) in human cell cultures: Growth factor release and contradictory results. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2010, 110, 418–421.

- Inchingolo, F.; Cantore, S.; Dipalma, G.; Georgakopoulos, I.; Almasri, M.; Gheno, E.; Motta, A.; Marrelli, M.; Farronato, D.; Ballini, A.; et al. Platelet rich fibrin in the management of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A clinical and histopathological evaluation. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2017, 31, 811–816.

- Dohan Ehrenfest, D.M.; Bielecki, T.; Del Corso, M.; Inchingolo, F.; Sammartino, G. Shedding light in the controversial terminology for platelet-rich products: Platelet-rich plasma (PRP), platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), platelet-leukocyte gel (PLG), preparation rich in growth factors (PRGF), classification and commercialism. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2010, 95, 1280–1282.

- Tatullo, M.; Marrelli, M.; Cassetta, M.; Pacifici, A.; Stefanelli, L.V.; Scacco, S.; Dipalma, G.; Pacifici, L.; Inchingolo, F. Platelet Rich Fibrin (P.R.F.) in reconstructive surgery of atrophied maxillary bones: Clinical and histological evaluations. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2012, 9, 872–880.

- Liu, L.; Wei, Q.; Alvarez, X.; Wang, H.; Du, Y.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, H.; Zhou, J.; Lam, P.; Zhang, L.; et al. Epithelial cells lining salivary gland ducts are early target cells of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in the upper respiratory tracts of rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 4025–4030.

- Lonsdale, J.; Thomas, J.; Salvatore, M.; Phillips, R.; Lo, E.; Shad, S.; Hasz, R.; Walters, G.; Garcia, F.; Young, N.; et al. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 580–585.

- Chen, L.; Zhao, J.; Peng, J.; Li, X.; Deng, X.; Geng, Z.; Shen, Z.; Guo, F.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, Y.; et al. Detection of 2019-nCoV in Saliva and Characterization of Oral Symptoms in COVID-19 Patients; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2020.

- Infezione da Coronavirus SARS-Cov2 ed un’analisi del Recettore ACE2. Microbiol. Ital. 2020. Available online: (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Mallineni, S.K.; Innes, N.P.; Raggio, D.P.; Araujo, M.P.; Robertson, M.D.; Jayaraman, J. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Characteristics in children and considerations for dentists providing their care. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2020, 30, 245–250.

- Kaufman, E.; Lamster, I.B. The diagnostic applications of saliva—A review. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2002, 13, 197–212.

- Zhang, C.-Z.; Cheng, X.-Q.; Li, J.-Y.; Zhang, P.; Yi, P.; Xu, X.; Zhou, X.-D. Saliva in the diagnosis of diseases. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2016, 8, 133–137.

- Rodríguez-Morales, A.J.; MacGregor, K.; Kanagarajah, S.; Patel, D.; Schlagenhauf, P. Going global—Travel and the 2019 novel coronavirus. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 33, 101578.

- To, K.K.-W.; Tsang, O.T.-Y.; Yip, C.C.-Y.; Chan, K.-H.; Wu, T.-C.; Chan, J.M.-C.; Leung, W.-S.; Chik, T.S.-H.; Choi, C.Y.-C.; Kandamby, D.H.; et al. Consistent Detection of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Saliva. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020.

- Ratnesar-Shumate, S.; Williams, G.; Green, B.; Krause, M.; Holland, B.; Wood, S.; Bohannon, J.; Boydston, J.; Freeburger, D.; Hooper, I.; et al. Simulated Sunlight Rapidly Inactivates SARS-CoV-2 on Surfaces. J. Infect. Dis. 2020.

- Simulated Sunlight Kills SARS CoV-2 on Surfaces in 7 to 14 Minutes. Available online: (accessed on 25 June 2020).