| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WesamEldin I. A. Saber | + 3257 word(s) | 3257 | 2021-03-05 07:55:50 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 3257 | 2021-03-17 02:10:07 | | | | |

| 3 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 3257 | 2021-03-18 07:28:03 | | |

Video Upload Options

During preservation, Jerusalem artichoke (JA) tubers are subjected to deterioration by mold fungi under storage, which signifies a serious problem. A new blue mold (Penicillium polonium) was recorded for the first time on JA tubers. Penicillium mold was isolated, identified (morphologically, and molecularly), and deposited in GenBank; (MW041259). The fungus has a multi-lytic capacity, facilitated by various enzymes capable of severely destroying the tuber components. An economic oil-based procedure was applied for preserving and retaining the nutritive value of JA tubers under storage conditions. Caraway and clove essential oils, at a concentration of 2%, were selected based on their strong antifungal actions. JA tubers were treated with individual oils under storage, kept between peat moss layers, and stored at room temperature. Tubers treated with both oils exhibited lower blue mold severity, sprouting and weight loss, and higher levels of carbohydrates, inulin, and protein contents accompanied by increased levels of defense-related phytochemicals (total phenols, peroxidase, and polyphenol oxidase). Caraway was superior, but the results endorse the use of both essential oils for the preservation of JA tubers at room temperature, as an economic and eco-safe storage technique against the new blue mold.

1. Introduction

Fruits and vegetables are consumed fresh. Improper postharvest handling causes rapid deteriorations in the quality of fresh produce and, in some cases, this results in products not reaching consumers at a satisfactory quality. The main cause of fruit deterioration is dehydration, with subsequent weight loss, color changes, softening, surface pitting, browning, loss of acidity, and microbial spoilage [1]. The majority of significant fruit losses result from decay caused by fungi such as Penicillium (green mold), Botrytis, Monilia, and others, leading to color changes and softening, accompanied by various economic losses that are dependent on the fruit type and storage conditions [2][3]. Moreover, the presence of Penicillium spp. may expose the health of the ultimate consumers to possible risk, since the fungus is usually linked to the production of mycotoxins, e.g., patulin; harmful metabolites which are detrimental to human health [4][5].

Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus L. family: Asteraceae) is a tuber-producing plant. In addition to being used as livestock fodder and in the production of biofuels, its tubers are consumed in human food and some functional-food ingredients because of their high nutritive value and polysaccharides contents, such as inulin, and oligofructose [6][7]. Under storage conditions, several fungi associated with rotted JA tubers have been reported, which vary in their disease potentiality and economic significance, e.g., Sclerotium rolfsii, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum [8][9][10], Botrytis cinerea, Rhizopus stolonifera, Penicillium, and Fusarium species [11], and Rhizoctonia solani [12].

In addition to the health hazards of manufactured fungicides, the development of pathogen resistance is another problem. The fungicides of biological origin, such as essential oils, representing a promising alternative approach not only for controlling postharvest decay but also for delaying the natural deterioration of stored fruits [13]. In general, such oils could be used as natural additives to extend shelf-life during the preservation of stored fruits. The levels of essential oils and their ingredients are determent factors in this respect [14]. Furthermore, essential oils represent ecofriendly, biodegradable, multifunctional, and nonpersistent natural products that reduce the risk of pathogen resistance build-up against chemicals because they contain two or more stereoisomers that target multi-sites on the pathogen’s cell membrane [9].

Essential oils, including clove (Syzygium aromaticum L. Merr. and Perr.) and caraway (Carum carvi L.), have been widely used in folk medicine as digestive, carminative, and lactogenic, antidiabetic, and analgesic therapeutic agents. Additionally, many other pharmacological aspects of such oils—importantly, their antioxidant, antiseptic, antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and insecticidal properties—have been reported [15].

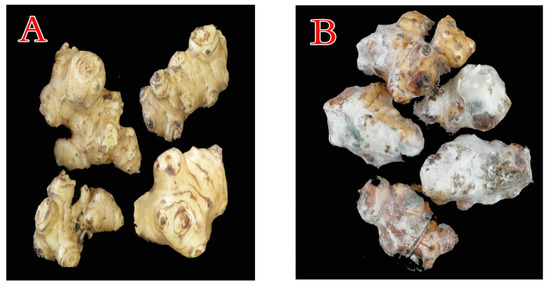

During 2019 (November up to March at Ismailia, Dakahlia, and Cairo provinces, Egypt) survey of post-harvest diseases of cool-stored JA tubers, a significant economic loss caused by blue mold was observed. The initial symptoms of blue mold include sections of—or the entire tuber tissue—displaying a soft, watery, discolored appearance, followed by the emergence of a dense white mycelium, which, with age, rapidly becomes covered with bluish spores (Figure 1). Finally, the whole tubers decompose and ferment. This process is accompanied by the production of bad odors. Such decayed samples were gathered, for further follow-up during the current study.

Figure 1. Tubers of Jerusalem artichoke (JA) stored under cooling conditions, showing the healthy (A) and blue mold decayed (B) tubers.

2. The Blue Mold

2.1. Isolation, Morphological, and Microscopic Identification

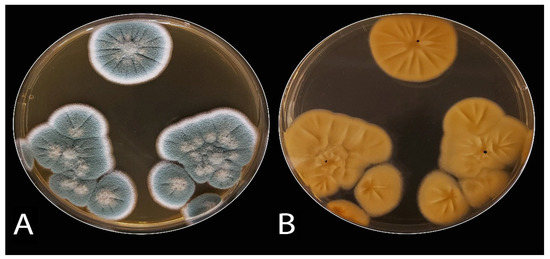

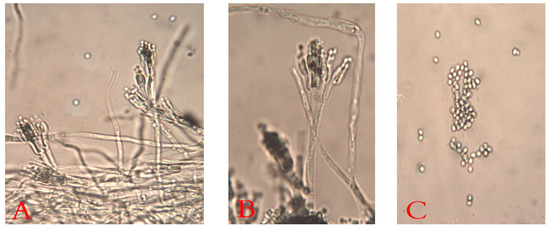

The decayed JA tubers stored under cooling conditions and with the typical symptoms of blue mold were selected. They were mostly specified as belonging to Penicillium spp. The Penicillium isolates (ARS20, ARS21, and ARS22) were subjected to further characterization. The initial morphological investigation on PDA, CDA, and MEA media at 25 ± 2 °C after 7 days showed blue–green, velutinous on MEA. Colonies for the three isolates have a distinct reverse, often with a yellow–brown color (Figure 2). The mean colony diameters (mm) for ARS20, ARS21 and ARS22 were 28.9 ± 0.96, 27.6 ± 0.50 and 29.8 ± 0.65 (on PDA), 31.56 ± 0.53, 30.6 ± 0.75, and 30.97 ± 0.6 (on MEA) and 28.56 ± 0.53, 29.21 ± 0.42, and 30.10 ± 0.4 (on CDA), respectively. The microscopic examination of the colonies revealed two-stage branched conidiophores, adpressed phialides with rough-walled stipes, and conidia that were smooth, globose to sub-globose, and borne in columns. Conidial dimensions for ARS20 were 3.0–3.6 (3.15) × 2.6–3.4 (2.9) μm, for ARS21 were 2.85–3.35 (3.1) × 2.57–3.55 (3.0) and for ARS22 were 2.95–3.8 (3.32) × 2.7–3.65 (3.16) μm in diameter (Figure 3). The three isolates displayed the typical characteristics of P. polonicum K. Zaleski.

Figure 2. Colony morphology of P. polonicum on malt extract agar (MEA) medium: (A) obverse and (B), reverse.

Figure 3. Microscopic micrograph of P. polonicum shows the typical terverticllate conidiophores ((A,B), at ×400) with smooth septate stripes and the spherical conidia ((C), at ×400).

3. Discussion

Isolation of the blue mold pathogen was performed, applying Koch’s postulates to ensure the precise determination of the causal microorganism. Following isolation, analysis of the morphological and microscopic features represents the first and most basic route for fungal identification. Investigation of the three blue mold isolates showed that their characteristics were in accordance with P. polonicum [16][17]. Penicillium is one of the largest and most important genera of microscopic fungi, with over 400 described species distributed worldwide. Its name comes from the Latin “penicillus”, which refers to the brush-like appearance of the conidiophores that resemble a painter’s brush [18]. Subsequent to visual identification, molecular identification methods were used.

Regarding the pathogenicity test, the three isolates of P. polonicum exhibited various degrees of disease severity. Isolates recovered from the artificially inoculated tubers showed the same morphological characteristics as those that previously appeared in the case of natural infection under storage that comes in agreement with Koch’s postulates. To our knowledge, this is the first report of P. polonicum on stored JA tubers. Previously, Penicillium spp. were reported as the most form of common storage rot pathogen, but specific species were not previously identified [8][11]. Confirmatory, P. polonicum has previously been reported as a psychro-tolerant xerophilic fungus that is associated with the spoilage of many foods and food products, such as peanuts, cereals, yam tubers, kiwifruit fruits, onions, and green table olives [16][17][19][20][21].

In order to ensure accuracy and confirmation, molecular identification is usually performed. This is highly sensitive and specific, with it being largely applied for the rapid identification of various fungi. The well-identified sequence—used for phylogeny creation—is fully annotated and shows a firm correlation with the other comparable fungal strains in the GeneBank database. Both ITS4 and ITS5 primers were used to amplify the nucleotide sequencing of the ITS region. This fragment region is uniform in a wide variety of fungal groups. This, in turn, aids in revealing the interspecific and, in some situations, intraspecific variation among organisms [22]. Furthermore, the sequences of this non-functional region are often extremely variable among fungal species [23], which is why such a region can be sufficient for fungal identification at the species level [24]. Technically, the repeated or multi-copy feature of the rDNA makes the ITS regions easy to amplify from a tiny sample of DNA [23]. Therefore, nucleotide sequencing of the ITS region is considered to provide quick and highly precise identification results compared to most other markers. Additionally, this can be used for barcode identification of a very broad group of fungi [25]. Interestingly, the molecular identification of P. polonicum ARS20 is in harmony with the morphological identification, with both identification methods confirming that the isolated blue mold (ARS20) is P. polonicum.

Clove and caraway oils showed a gradual reduction in fungal growth with increasing concentrations of both oils. Oils are known to inhibit fungal growth. The antifungal activity of caraway essential oil may be attributed to various antifungal phytochemicals that constitute a large fraction of the oil, such as carvone, limonene, carveol, pinen, and thujone [9]. The antagonistic feature of clove oil can be attributed to the presence of an aromatic nucleus and phenolic OH-group that can react with the phospholipids of the cell membrane, changing their permeability features [10]. Essential oils could be used as natural additives in the food industry, without the fear of potential health hazards, as well as in postharvest treatment to increase shelf-life due to their antifungal, antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-carcinogenic properties [14].

The GC analysis revealed various components of the clove and caraway essential oils, with fractions showing evident antifungal capacity, which varied according to the distribution of the components of each fraction. The GC analysis showed an increase in the proportion of oxygenated compounds in caraway fractions in comparison to hydrocarbons, therefore, caraway oil could be considered to be highly oxygenated while clove oil is moderately oxygenated. Previously, oxygenated compounds have been reported to have bioactive inhibitory effects against several fungal strains, including numerous Penicillium strains, such activity of the oil could be attributed to the oxygenated carvone that possessed higher antifungal activity, as well as antioxidant activity [26][27][28]. Such compounds could also inhibit the rate of primary and the secondary oxidation product formation. Furthermore, the physical nature of the rich oxygenated essential oils, for example, their low molecular weight combined with a lipophilic character, allow them to penetrate the cell membrane more quickly compared to other substances [27][29]. Clove oil also showed good potential in inhibiting the growth of Penicillium polonium. The hydroxyl group on eugenol (the major component of clove oil) is thought to bind to cellular proteins, preventing the catalytic action of various fungal enzymes [30]

Contrarily to caraway and clove oils, mint and artemisia supported fungal growth at the initial concentration but slightly reduced growth with the advance of concentration levels. Mint slightly encouraged fungal growth at all tested concentrations; therefore, the two oils were omitted in the rest of the investigation.

The enzymatic profile of P. polonicum showed marked activity of various hydrolytic enzymes, in the absence of the two oils, the fungus was able to produce nearly all cell-wall degrading enzymes (CWDE) that are known to be involved in the plant–pathogen interaction. These enzymes facilitate the infection route via the maceration of plant tissue.

The plant cell wall is a physical barrier against pathogenic invasion. Phytopathogenic fungi produce an array of CWDEs to invade host tissues through the degradation of cell wall components of plants [31]. Cell wall degrading enzymes are thought to help pathogens directly penetrate host tissues, and therefore, may be essential for pathogenicity.

The mode of action of every CWDE has already been reported. FPase (the overall cellulolytic activity of cellulase enzymes) works on cellulose that is widely distributed in plant cell walls. The hydrolysis of cellulose is accomplished by components of cellulase, including randomly acting endoglucanse, two exoglucanases (cellodextrinases and cellobiohydrolases), and β-glucosidase, that completely degrade cellulose into glucose units [32][33][34].

Xylanase (hemicellulose-degrading enzymes) manages the hydrolysis of xylan (the main part of the hemicellulose fraction). This process requires the combined action of various xylanases, including endo-1,4-β-xylanase; β-D-xylosidases; and acetylxylan esterase, resulting in the release of xylose monomers [35][36].

Pectin-degrading enzymes are another important group of CWDEs. Two major classes of pectinase (esterases and depolymerases) are known. PGase is the main kind of heterogeneous pectinase, which aids the hydrolysis of pectin polymers by cleaving the α-1,4-glycosidic bond, releasing galacturonic acid [37][38].

Amylase is a starch-degrading enzyme, the catalytic action of this enzyme (group β-amylase and γ-amylase) leads to the full hydrolysis of starch into simple monomers of glucose [39].

Inulinases and invertase act as β-fructosidases. Inulinases hydrolyze inulin to liberate fructose units in a single step from the non-reducing end, by the action of two main enzymes (endoinulinase—which is specific for inulin—and exoinulinase [40][41][42]). Invertases (β-fructofuranosidases) are a large group of glycoside hydrolases, which catalyze the hydrolysis of sucrose to an equimolar mixture of glucose and fructose—both inulinases. Invertase enzymes are active on sucrose and, more, possess the unique feature of being able to hydrolyze inulin [43][41].

Finally, the hydrolysis of nitrogenous compounds is mainly mediated by the action of several kinds of proteases that cleave protein into peptides and amino acids [44]. Depending upon the type of the reaction, proteases are sectioned into exopeptidases that catalyze the terminal peptide bond, and endopeptidases that cleave the non-terminal bonds between amino acids [45].

Interestingly, FPase, xylanase, and PGase were found in the filtrate of the pathogen, despite the composition of JA tubers lacking cellulose and xylan in their structure. The main reason explaining such data is based on the secretion nature of enzymes by the microorganism, which is either induced, constitutive, or both. The induced (inducible) enzyme is one whose secretion requires—or is stimulated by—a specific inducer (substrate). Whereas, the constitutive enzyme is on that is produced by a microorganism, regardless of the presence or absence of the specific substrate [41]. This leads to the conclusion that the current pathogen may have both mechanisms of enzyme secretion, representing an additional threat to JA tubers in storage.

Contrarily, the presence of an inducer substrate in the tuber components induces the synthesis of amylase, inulinase, invertase, and protease. These enzymes could also be constitutive. Such a complementary enzymatic system supports the observations of fungal survival under field and storage conditions. In addition to the enzymes described above, other accessory enzymes are required to cleave the linkage to side chains, i.e., side-chain cleaving enzymes, such as methyl esters and acetylation, or to split linkages to lignin [31].

As discussed earlier, different CWDEs, such as cellulases, hemicellulases, pectinases, and proteases work together to crack up the plant cell walls for the entrance of a pathogen, therefore, this group ultimately works to degrade the outer part of the JA tubers. On the other side, there are other enzymes (amylase, inulinase, and invertase) that work on the degradation of the cell components. This latter group is expected to catalyze the degradation of sugar contents of the tuber. JA tubers are rich in inulin and various other sugars that represent a suitable substrate for these enzymes. Additionally, the tubers have a wide array of vitamins, minerals, and amino acids [11], representing a nutritious medium that supports fungal growth and development during the pathogenesis process.

The current pathogenic P. polonicum has a complementary profile of hydrolytic enzymes, which is why P. polonicum causes a serious mold and completely deteriorates JA tubers under storage. Fortunately, this tight enzymatic capacity disappeared after the application of oils, with both oils showing a strong inhibition impact on both growth and enzymatic production systems. The enzymatic deactivation of essential oils is a mutual interaction between the microorganism, oil components, and concentration, for example, the eugenol content of clove oil as well as, the presence of an aromatic nucleus and phenolic OH-group can react with the target enzyme, resulting in the deactivation of enzymes, and alteration of the cell membrane [10]. This combined action leads to inhibition of all the biological processes of the microorganism.

During preservation, storage causes undesirable changes in the JA tubers. Storage usually results in high losses in quality, caused mainly by rotting, desiccation, sprouting, freezing, and inulin degradation. Concerning the disease severity, storage-fungi represent a serious problem, since plant infection takes place in the field and then extends to the storage [7][8], during which, the pathogen can grow on tubers that represent the natural preferred conditions for fungal growth. However, both oils succeeded in greatly minimizing the deleterious action of the pathogen, likely due to the possible modes of action discussed above. Regarding the defense-related phytochemicals, peroxidase is a key enzyme in defense-related processes, including the accumulation of lignin and phenolic compounds and suberization. The polyphenol oxidase enzyme catalyzes the oxidation of phenols to quinines, which are substances that are highly toxic to the pathogen, while phenolic compounds contribute to resistance through their antimicrobial properties against the pathogen. The increase in these oxidative enzymes and the phenol content is associated with the increase in plant resistance against fungal infection [10].

The structural features of JA tubers under storage showed marked variations. The presence of the pathogen caused a pronounced reduction in the dry matter in the infected control, accompanied by a gradual increment in sprouting, as well as weight loss. This principally suggests a loss of a certain quantity of water from the tuber. Moreover, during long-term exposure to storage conditions (without EOs application), shrinking and water losses were recorded in tubers.

Tuber sprouting occurred during storage when dormancy was broken and sprouting was activated, leading to an accelerated loss of water through the permeable surface of the sprout. This also leads to physiological aging of tubers, resulting in weight and quality losses [46].

During the current trial, peat moss was used which is traditionally used in food preservation because of its antimicrobial activity. This antimicrobial activity is possibly attributable to some of its bioactive components, such as sphagnan, a pectin-like polymer that inhibits microbial growth via electrostatic immobilization of extracellular enzymes and/or nitrogen deprivation, in addition to phenolics that inhibit the activity of extracellular enzymes of microbes, or other constituents such as sterols and polyacetylenes [47]. Peat moss has been approved as a storage medium; it has a relatively high-water retention capacity of up to 16–25 times its dry weight [48], providing a relatively low humidity around the tubers that blocks heat transfer within the peat moss, leading to decreases in water loss even during storage at 25 °C. However, dry matter content in JA tubers depends on many factors, such as storage conditions [49].

Pure carvone oil has a pronounced impact as a suppressor of potato tuber germination during storage. The main biomarker for the validity of potato tuber antioxidant enzyme activities (peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase) was detected [46]. Moreover, the sprouting inhibition by caraway oil was accompanied by significantly decreased weight loss [50]. The active compounds, limonene, and carvone, in caraway oil, are known to suppress the sprouting of potato tubers via the inhibition of mitochondrial respiration and reducing carbohydrate degradation sugars [51]. Carvone may play a more specific role in the sprout growth of potato tubers, such as by inhibiting the key enzyme in the mevalonate pathway, which is the main pathway of gibberellin biosynthesis [52].

Eugenol oil inhibits the eye sprouts by causing necrotic injury in the apical meristem of the bud, leading to sprouting necrosis [53]. Eugenol can reduce the rate of sprout growth during storage in non-dormant tubers. Additionally, eugenol showed the least number of sprouts and shortest sprouts, while eugenol can also reduce sugars in the treated tubers, a process that appears to occur due to lower consumption levels of soluble carbohydrates [54].

Carbohydrates, inulin, and protein contents varied during storage according to the treatments, both oils minimized the development of the deterioration process. A fresh JA tuber contains up to 80% water, 10.6–17.3% carbohydrates—mainly in the form of inulin (7–30%)—and about 2–8% protein [6][7][55]. However, these contents vary due to several reasons, such as variety, climatic changes, and storage conditions. For the long-term storage of JA tubers, there are various microbiological, enzymatic, and biochemical alterations, which may lead to tuber damage in carbohydrate and protein chemistry. However, the basic constituents of caraway oil (monoterpenes) tend to delay the breakdown of tuber components associated with the enzymatic system, as well as respiration and energy metabolic enzymes, maintaining the internal biochemical enzymatic activities at a minimum level [15].

References

- Serrano, M.; Romero, D.; Guillen, F.; Valverde, J.; Zapata, P.J.; Castillo, S.; Valero, D. The addition of essential oils to MAP as a tool to maintain the overall quality of fruits. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, 464–471.

- Du Plooy, W.; Regnier, T.; Combrinck, S. Essential oil amended coatings as alternatives to synthetic fungicides in citrus postharvest management. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2009, 53, 117–122.

- Castillo, S.; Navarro, D.; Zapata, P.J.; Guillen, F.; Valero, D.; Serrano, M.; Martínez-Romero, D. Antifungal efficacy of Aloe vera in vitro and its use as a preharvest treatment to maintain postharvest table grape quality. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2010, 57, 183–188.

- Samson, R.A.; Hoekstra, E.S.; Frisvad, J.C.; Filtenborg, O. Introduction to Food and Airborne Fungi; Central Bureau Voor Schianmel cultures (CBS): Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; p. 389. Available online: (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Chen, L.; Guo, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, J.; Liu, T.; Chen, W.; Liang, D.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, Q.; et al. Occurrence and characterization of fungi and mycotoxins in contaminated medicinal herbs. Toxins 2020, 12, 30.

- Lakíc, Ž.; Balalíc, I.; Nožiníc, M. Genetic variability for yield and yield components in Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus L.). Genetika 2018, 50, 45–57.

- Bogucka, B.; Pszczółkowska, A.; Okorski, A.; Jankowski, K. The effects of potassium fertilization and irrigation on the yield and health status of Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus L.). Agronomy 2021, 11, 234.

- El-Awady, A.A.; Ghoneem, K.M. Natural treatments for extending storage life and inhibition fungi disease of Jerusalem artichoke fresh tubers. J. Plant Prod. Mansoura Univ. 2011, 2, 1815–1831.

- Ghoneem, K.M.; Saber, W.I.A.; El-Awady, A.A.; Rashad, Y.M.; Al-Askar, A.A. Alternative preservation method against Sclerotium tuber rot of Jerusalem artichoke using natural essential oils. Phytoparasitica 2016, 44, 341–352.

- Ghoneem, K.M.; Saber, W.I.A.; El-Awady, A.A.; Rashad, Y.M.; Al-Askar, A.A. Clove essential oil for controlling white mold disease, sprout suppressor and quality maintainer for preservation of Jerusalem artichoke tubers. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2016, 26, 601–608.

- Kays, S.J.; Nottingham, S.F. Biology and Chemistry of Jerusalem Artichoke: Helianthus tuberosus L.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 9781420044959.

- Ezzat, A.E.S.; Ghoneem, K.M.; Saber, W.I.A.; Al-Askar, A.A. Control of wilt, stalk and tuber rots diseases using arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, Trichoderma species and hydroquinone enhances yield quality and storability of Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus L.). Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2015, 25, 11–22.

- Marino, M.; Bersani, C.; Comi, G. Impedance measurements to study the antimicrobial activity of essential oils from Lamiaceae and Compositae. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 67, 187–195.

- Tzortzakis, N.G.; Economakis, C.D. Antifungal activity of lemongrass (Cympopogon citratus L.) essential oil against key postharvest pathogens. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2007, 8, 253–258.

- Mutlu-Ingok, A.; Devecioglu, D.; Dikmetas, D.N.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F.; Capanoglu, E. Antibacterial, antifungal, antimycotoxigenic, and antioxidant activities of essential oils: An updated review. Molecules 2020, 25, 4711.

- Frisvad, J.C.; Samson, R.A. Polyphasic taxonomy of Penicillium subgenus Penicillium. A guide to identification of food and air-borne terverticillate Penicillia and their mycotoxins. Stud. Mycol. 2004, 49, 1–173.

- Duduk, N.; Vasić, M.; Vico, I. First report of Penicillium polonicum causing blue mold on stored onion (Allium cepa) in Serbia. Plant Dis. 2014, 2014. 98, 1440.

- Yin, G.; Zhang, Y.; Pennerman, K.K.; Wu, G.; Hua, S.S.T.; Yu, J.; Jurick, W.M.; Guo, A.; Bennett, J.W. Characterization of blue mold Penicillium Species isolated from stored fruits using multiple highly conserved loci. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 12.

- Çakır, E.; Maden, S. First report of Penicillium polonicum causing storage rots of onion bulbs in Ankara province, Turkey. New Dis. Rep. 2015, 32, 24.

- Khalil, A.M.A.; Hashem, A.H.; Abdelaziz, A.M. Occurrence of toxigenic Penicillium polonicum in retail green table olives from the Saudi Arabia market. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 101314.

- Wang, C.W.; Ai, J.; Lv, H.Y.; Qin, H.Y.; Yang, Y.M.; Liu, Y.X.; Fan, S.T. First report of Penicillium expansum causing postharvest decay on stored kiwifruit (Actinidia arguta) in China. Plant Dis. 2015, 99, 1037.

- Inglis, P.W.; Tigano, M.S. Identification and taxonomy of some entomopathogenic Paecilomyces spp. (Ascomycota) isolates using rDNA-ITS sequences. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2006, 29, 132–136.

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T.D. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes-application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118.

- Raja, H.A.; Miller, A.N.; Pearce, C.J.; Oberlies, N.H. Fungal identification using molecular tools: A primer for the natural products research community. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 756–770.

- Schoch, C.L.; Seifert, K.A.; Huhndorf, S.; Robert, V.; Spouge, J.L.; Levesque, C.A.; Chen, W. Fungal Barcoding Consortium. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6241–6246.

- Combrinck, S.; Regnier, T.; Kamatou, G.P.P. In vitro activity of eighteen essential oils and some major components against common postharvest fungal pathogens of fruit. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 33, 344–349.

- Salha, G.B.; Díaz, R.H.; Lengliz, O.; Abderrabba, M.; Labidi, J. Effect of the chemical composition of free-Terpene hydrocarbons essential oils on antifungal activity. Molecules 2019, 24, 3532.

- Ibrahim, G.S.; Kiki, M.J. Chemical composition, antifungal and antioxidant activity of some spice essential oils. Int. J. Life Sci. Pharma Res. 2020, 10, 43–50.

- Darougheh, F.; Barzegar, M.; Sahari, M.A. Antioxidant and anti-fungal effect of caraway (Carum Carvi L.) essential oil in real food system. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2014, 10, 70–76.

- Burt, S. Essential oils: Their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods-a review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253.

- Kubicek, C.P.; Starr, T.L.; Glass, N.L. Plant cell wall–degrading enzymes and their secretion in plant-pathogenic fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014, 52, 427–451.

- Saber, W.I.A.; El-Naggar, N.E.; AbdAl-Aziz, S.A. Bioconversion of lignocellulosic wastes into organic acids by cellulolytic rock phosphate-solubilizing fungal isolates grown under solid-state fermentation conditions. Res. J. Microbiol. 2010, 5, 1–20.

- Badhan, A.K.; Chadha, B.S.; Kaur, J.; Saini, H.S.; Bhat, M.K. Production of multiple xylanolytic and cellulolytic enzymes by thermophilic fungus Myceliophthora sp. IMI 387099. Biores. Technol. 2007, 98, 504–510.

- Saber, W.I.A.; El-Naggar, N.E.; El-Hersh, M.S.; El-Khateeb, A.Y. An innovative synergism between Aspergillus oryzae and Azotobacter chroococcum for bioconversion of cellulosic biomass into organic acids under restricted nutritional conditions using multi-response surface optimization. Biotechnology 2015, 14, 47–57.

- Bailey, M.J.; Beily, P.; Poutanen, K. Interlaboratory testing and methods for assay of xylanase activity. J. Biotechnol. 1992, 23, 257–270.

- Caufrier, F.; Martinou, A.; Dupont, C.; Bouriotis, V. Carbohydrate esterase family 4 enzymes: Substrate specificity. Carbohydr. Res. 2003, 338, 687–692.

- Bai, Z.H.; Zhang, H.X.; Qi, H.Y.; Peng, X.W.; Li, B.J. Pectinase production by Aspergillus niger using wastewater in solid state fermentation for eliciting plant disease resistance. Bioresour. Technol. 2004, 95, 49–52.

- Tuoping, L.; Wang, N.; Li, S.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, M. Optimization of covalent immobilization of pectinase on sodium alginate support. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 29, 1413–1416.

- Saranraj, P.; Stella, D. Fungal amylase—A review. Int. J. Microbiol. Res. 2013, 4, 203–211.

- Ohta, K.; Suetsugu, N.; Nakamura, T. Purification and properties of an extracellular inulinase from Rhizopus sp. Strain TN-96. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2002, 1, 78–80.

- Saber, W.I.A.; El-Naggar, N.E. Optimization of fermentation conditions for the biosynthesis of inulinase by the new source; Aspergillus tamarii and hydrolysis of some inulin containing agro-wastes. Biotechnology 2009, 8, 425–433.

- El-Hersh, M.S.; Saber, W.I.A.; El-Naggar, N.E. Production strategy of inulinase by Penicillium citrinum AR-IN2 on some agricultural by-products. Microbiol. J. 2011, 1, 79–88.

- AbdAl-Aziz, S.A.A.; El-Metwally, M.M.; Saber, I.A. Molecular identification of a novel inulinolytic fungus isolated from and grown on tubers of Helianthus tuberosus and statistical screening of medium components. World J. Microb. Biot. 2012, 28, 3245–3254.

- El-Hersh, M.S.; Saber, W.I.; El-Fadaly, H.A. Amino acids associated with optimized alkaline protease production by Bacillus subtilis ATCC 11774 using statistical approach. Biotechnology 2014, 13, 252–262.

- Gurumallesh, P.; Alagu, K.; Ramakrishnan, B.; Muthusamy, S. A systematic reconsideration on proteases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 128, 254–267.

- Afify, A.M.R.; El-Beltagi, H.S.; Aly, A.A.; El-Ansary, A.E. Antioxidant enzyme activities and lipid peroxidation as biomarker for potato tuber stored by two essential oils from caraway and clove and its main component carvone and eugenol. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, S772–S780.

- Børsheim, K.Y.; Christensen, B.E.; Painter, T.J. Preservation of fish by embedment in Sphagnum moss, peat or holocellulose: Experimental proof of the oxopolysaccharidic nature of the preservative substance and of its antimicrobial and tanning action. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2001, 2, 63–74.

- Taskila, S.; Särkelä, R.; Tanskanen, J. Valuable applications for peat moss. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2016, 6, 115–126.

- Cabezas, M.J.; Rabert, C.; Bravo, S.; Shene, C. Inulin and sugar contents in Helianthus tuberosus and Cichorium intybus tubers: Effect of postharvest storage temperature. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 2860–2865.

- Şanlı, A.; Karadoğan, T. Carvone containing essential oils fas sprout suppressants in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tubers at different storage temperatures. Potato Res. 2019, 62, 345–360.

- Gómez-Castillo, D.; Cruz, E.; Iguaz, A.; Arroqui, C.; Vírseda, P. Effects of essential oils on sprout suppression and quality of potato cultivars. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 82, 15–21.

- Oosterhaven, K.; Hartmans, K.J.; Scheffer, J.J.C. Inhibition of potato sprout growth by carvone enantiomers and their bioconversion in sprouts. Potato Res. 1995, 38, 219–230.

- Finger, F.L.; Santos, M.M.S.; Araujo, F.F.; Lima, P.C.C.; da Costa, L.C.; França, C.F.M.; Queiroz, M.C. Action of essential oils on sprouting of non-dormant potato tubers. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2018, 61, e18180003.

- Santos, M.N.S.; Araujo, F.F.; Lima, P.C.C.; Costa, L.C.; Finger, F.L. Changes in potato tuber sugar metabolism in response to natural sprout suppressive compounds. Acta Scientiarum. Agron. 2020, 42, e43234.

- Al-Snafi, A.E. Medical importance of Helianthus tuberosus—A review. Indo Am. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 05, 2159–2166.