| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vladimir MULENS-ARIAS | + 4108 word(s) | 4108 | 2020-05-09 08:38:57 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | -29 word(s) | 4079 | 2020-10-28 09:29:02 | | |

Video Upload Options

The unique physical properties (physical identity) of iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs), their ample possibilities for surface modifications (synthetic identity), and the complex dynamics of their interaction with biological systems (biological identity) make IONPs a unique and fruitful resource for developing magnetic field-based therapeutic and diagnostic approaches to the treatment of diseases such as cancer. In this entry, we revisited the current knowledge on IONP interaction with cells of the mononuclear phagocytic system (macrophages), dendritic cells (DCs), endothelial cells (ECs), and cancer cells, correlating synthetic identity with the biological effects that IONPs trigger in these cells (biological identity). Furthermore, we thoroughly discuss current understandings of the basic molecular mechanisms and complex interactions that govern IONP biological identity, and how these traits could be used as a stepping stone for future research.

1. Introduction

The cell type that the iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) encounter in the organism is highly relevant to their effects on biological systems. In the following sections, we summarize how IONPs can affect the biology of cells they are likely to interact with in an antitumor therapeutic setting. IONPs interact with myeloid cells specialized in the capture of particulate materials, such as macrophages or dendritic cells. As IONPs circulate through the vascular system, they also encounter endothelial cells. Finally, IONP also affects the tumor microenvironment. The following section provides an overview of how the presence of iron can affect these cell types. We also discuss the possibility of using these intrinsic biological properties of IONPs to enhance their activity in a therapeutic setting.

2. IONPs and Myeloid Cells

2.1. Iron Metabolism and Macrophage Polarization

The interactions and effects of metallic nanoparticles on macrophage activation have been a concern in terms of nanomaterial imaging/therapeutic efficacy and systemic nanotoxicity [1]. Iron oxide nanoparticles are among the most widely used nanomaterials, even in clinical settings, and thus the study of how they interact with myeloid cells is of great importance for researchers and clinicians. The relevance of iron in myeloid cells is exemplified by the involvement of this redox-active metal in several essential enzymes and protein regulators, all classified as hemoproteins, which participate in key cellular processes for macrophage activity in inflammation (e.g., NADPH oxidase 2, cyclooxygenases 1 and 2, inducible nitric oxide synthase). Macrophages are also central to the systemic trafficking of iron [2][3]. Splenic marginal metallophilic macrophages phagocytose senescent erythrocytes and release heme-derived iron back into circulation to support different systemic and local functions such as pro-inflammatory and bacteriostatic response [4][5]. Macrophages retain iron during inflammation as a result of the binding of the acute-phase protein, hepcidin, which mediates an increase in iron uptake and the internalization and degradation of the iron export transporter of the heme-free iron ferroportin [6]. A more detailed review of iron macrophages has been published elsewhere [7].

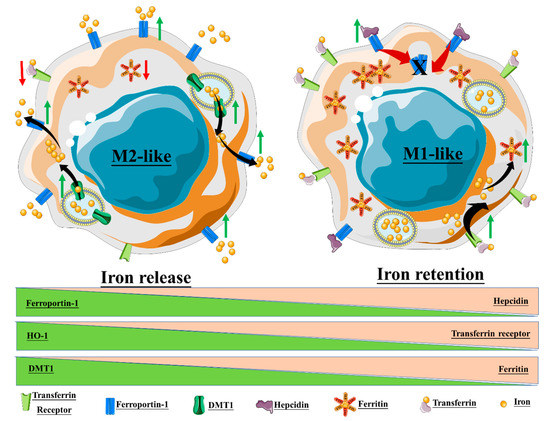

The macrophage response to iron is also affected by polarization, and in turn, iron can affect macrophage polarization (Figure 1). Recalcati et al. found that M2 macrophages express higher amounts of iron metabolism-related proteins, e.g., transferrin receptor (TfR1), iron-responsive proteins (IRP), and ferroportin (Fpn), when compared to unpolarized cells, while M1 macrophages downregulated these proteins. The M1 phenotype also endows macrophages with iron sequestration ability, while the M2 phenotype promotes iron release [8]. Exogenous iron can promote macrophage polarization toward an M1 phenotype through the production of ROS and, in consequence, enhance p300/CBP acyltransferase activity and the acetylation of p53 [9]. Intracellular iron also plays a crucial role in the M2-/M1-balance according to Agoro et al. Administration of an iron-rich diet in mice promoted the in vivo expression of high levels of the M2 markers Arg1 and Ym1 in the liver and peritoneal macrophages. More interestingly, an iron-rich diet prevented the mice from developing an LPS-induced inflammatory response through an M1–M2 reversion, while iron deficiency exacerbates the endotoxin-induced inflammatory response [10]. The latter finding was also corroborated by Pagani et al. when studying the response of iron-deprived mice to LPS challenge. These authors found that iron-deprived hepatic and splenic macrophages expressed higher levels of IL-6 and TNFα than those of healthy mice, indicating that iron content negatively regulates M1 response [11]. Nonetheless, the role of iron in the M1–M2 balance is not consistent throughout the literature (Table 1). Hoeft et al. observed that iron overloading aggravates LPS-induced inflammatory response in mice, most likely mediated by an increment in mitochondria biogenesis in iron-loaded macrophages [12]. An unrestrained M1 response has been described for iron overloading in chronic inflammatory diseases, such as atherosclerosis and chronic venous leg ulcers, through overproduction of hydroxyl radicals and TNFα [13]. Likewise, iron load appears to promote a persistent M1 macrophage population in the injured spinal cord which, in addition to TNFα expression, prevents the injury site from being properly repaired [14]. Due to the multiple effects of iron on macrophages, IONP degradation products therefore have the potential to alter macrophage polarization.

Table 1. A list of IONPs recently investigated for their effect on the macrophage.

|

Iron oxide nanoparticles |

Physical identity |

Synthetic identity (Surface coating) |

Cell type |

Described effects |

Mechanism |

|

Carboxymaltose@Fe2O3[15] |

Fe2O3 |

Carboxymaltose |

J774A.1 Primary macrophages |

Inhibits LPS-induced NO Inhibits IL-6 and TNFα secretion Hampers phagocytosis |

Decreased free glutathione |

|

PMA@IONPs (4 and 14 nm) [16] |

Fe3O4 |

PMA |

|

Hamper cell viability Promote extensive vacuolization Induce TNFα, CD86 and inhibit CD206 gene expression |

Promotion of extensive vacuolization |

|

PEGylated PMA@IONPs (4 and 14 nm) [16] |

Fe3O4 |

PEGylates PMA |

RAW264.7 |

Promote cell proliferation Promote extensive vacuolization Induce TNFα, CD86 and inhibit CD206 gene expression |

Promotion of extensive vacuolization |

|

PDSCE@IONPs [17] |

γ-Fe2O3 |

Polydextrose sorbitol carboxymethyl-ether |

In vivo and RAW264.7 |

Reduce the level of LPS-induced injury Induce a large amount of IL-10 Trigger autophagy |

Promotion of autophagy through Cav1-Notch1/HES1 |

|

Carboxydextran@IONPs [18] |

Fe3O4 |

Carboxydextran |

In vivo local administration and J774.2 |

Downmodulate CD86, MHC-II, Arg1 and CD163 expression (transient) Hamper phagocytosis (transient) |

N.A. |

|

SiO2@IONPs [19] |

γ-Fe2O3 |

SiO2 |

Peritoneal macrophages |

Increase gH2AX (marker for double-strand break) Increase IL-10 production |

N.A. |

|

Resovist [20] |

Fe3O4 γ-Fe2O3 |

Carboxydextran |

Primary macrophages and RAW264.7 |

Induce autophagy Induce pro-inflammatory gene expression (TNFα, IL-12, MIP-1-α, etc.) |

Promote autophagy through TLR4-p38-Nrf2-p62 signaling pathway |

|

Feraheme [20] |

Fe3O4 |

Carboxymethyl dextran |

|

Induce autophagy Induce pro-inflammatory gene expression (TNFα, IL-12, MIP-1-α, etc.) |

Promote autophagy through TLR4-p38-Nrf2-p62 signaling pathway |

|

DMSA@IONPs [21] |

Fe3O4 |

DMSA |

RAW264.7 |

Induce pro-inflammatory cytokines Promote cell proliferation Promote macrophage migration Promote macrophage-driven Hepa1-6 cell killing |

N.A. |

|

PEI@IONPs [22] |

Fe3O4 γ-Fe2O3 |

PEI |

RAW264.7, THP-1, and primary peritoneal macrophages |

Induce pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-12, IL-1β, TNFα, etc.) Activate macrophages (increase CD40, CD80, CD86 and I-A/I-E) Activate the MAPK-dependent pathway Promote podosome formation and reduce ECM degradation |

At least part of the effects are mediated by production of ROS and activation of TLR-4 |

|

Citrate@Fe3O4 of different shape (octopod, plate, cube, sphere) [23] |

Mn-doped Fe3O4 |

Citrate |

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) |

Activate inflammasome (IL-1β) Induce pyroptosis Induce ROS production In this order: Octopod > plate > cube > sphere |

Lysosome damage, ROS production, and K+ efflux, partially mediated by NLPR3 |

|

Alkyl-PEI@IONPs (30, 80, and 120 nm) [24] |

Fe3O4 |

Alkyl-PEI |

BMDMs |

Induce IL-1β nm > 80 nm > 120 nm) Lysosome damage ROS production |

Modulated by ROS |

|

Fe2O3@D-SiO2[25] |

Fe2O3 |

SiO2 |

RAW264.7 |

Increase CD80, CD86 and CD64 |

Activate NF-κB and IRF5 |

|

Fe3O4@D-SiO2[25] |

Fe3O4 |

SiO2 |

RAW264.7 |

Negligible effect |

N.A. |

|

DMSA@IONPs[26] |

Fe3O4 |

DMSA

|

M2-like THP1 BMDMs (M2) |

Induce ROS production Change Fe metabolism to an iron-replete status Reduce Mac3, CD80 Increase IL-10 production Decrease migration but increase invasion |

Activation of MAPK signaling |

|

APS@IONPs [26] |

Fe3O4 |

3-Aminopropyl triethoxysilane |

M2-like THP1 BMDMs (M2) |

Induce ROS production Change Fe metabolism to an iron-replete status Reduce Mac3, CD80 Increase IL-10 production Decrease migration but increase invasion |

Activation of MAPK signaling |

|

AD@IONPs[26] |

Fe3O4 |

Aminodextran |

M2-like THP1 BMDMs (M2) |

Induce ROS production Change Fe metabolism to an iron-replete status Reduce Mac3 Decrease migration but increase invasion |

Activation of MAPK signaling |

2.2. IONP Recognition by Macrophages and Activation

It has been proven that toll-like receptors mediate most macrophage reactions to iron oxide nanoparticles. We have demonstrated that polyethyleneimine-coated IONPs trigger macrophage activation, partially through TLR-4 engagement and production of ROS [22]. Autophagy is often activated upon nanoparticle phagocytosis, as demonstrated by Jin et al., who studied the effect of two FDA-approved iron-oxide nanoparticles, resovist, and ferumoxytol [20]. The macrophage-like cells RAW 264.7, enclosed iron oxide nanoparticles within the endosome, early autophagic vacuole, and eventually double-membrane autophagic vacuoles that contained nanoparticles, small internal vesicles, and cellular and membrane debris. These structural changes were accompanied by the formation of LC3 puncta and overexpression of sequestosome identified by p62/SQSTM1, an autophagy receptor that links ubiquitinated proteins and organelles with autophagosomes [27][28][29]. Noticeably, IONP-induced autophagy was mediated by the activation of the TLR4-p38-Nrf2 pathway rather than the classical autophagy machinery dependent on ATG5/12, as pre-treatment with the TLR4 signaling inhibitor, CLI-095, prevented IONP-loaded macrophages from exhibiting autophagic activities [20].

Another key issue for re-programmed macrophage-based therapies is related to interference by iron oxide nanoparticles with the adequate differentiation of monocytes into mature and competent macrophages. Vallegas et al. found out that poly(acrylic acid)-coated IONPs do not alter the viability of monocyte-derived macrophages during differentiation, but inhibit the secretion of LPS-induced cytokines such as IL1β, IL-6, and IL-10 [30]. Nonetheless, Dalzon et al. found that iron oxide carboxymaltose nanoparticles, known as FERINJECT®, do not significantly modulate LPS-induced cytokine profile in primary macrophages or hamper their ability to migrate towards a chemotactic stimulus, suggesting a clear dependence on IONP nature for macrophage activation status [31]. A clearer effect of the IONP on myeloid cells was described by Xu et al., who observed that ferumoxytol inhibits the suppressing functions of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) [32]. Contrasting with most reports in which IONPs were shown to act as ROS inductors, ferumoxytol treatment caused a ROS reduction in MDSCs, as evidenced by the decrease of the p47phox component of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate–oxidase (NOX) complex responsible for ROS production in MDSCs. Furthermore, ferumoxytol promotes bone marrow-derived MDSC differentiation into macrophages, reducing the appearance of these cells during sepsis-like scenarios. As a result, ferumoxytol ameliorates LPS-induced sepsis in mice [32].

It is equally important to understand how the different macrophage populations respond to IONP treatment, particularly as concerns approaches intended for imaging of MRI-visible macrophages, e.g., inflamed sites [33][34]. Each macrophage phenotype indeed expresses different factors involved in iron metabolism, and thus exhibits divergent iron sensitivity (Figure 1 and [8]). Zini et al. demonstrated that M2-polarized THP1 macrophages internalized significantly more IONPs than M1-polarized and M0 counterparts, leading to a higher T1 signal in M2 macrophages and a higher T2* signal in M0 macrophages [35]. Internalized IONPs could also, in turn, exert effects on polarization and iron metabolism. In one example, our group showed that DMSA-, APS-, and aminodextran-coated IONPs changed iron metabolism towards an iron-sequestering status in M2-like macrophage [26].

Figure 1. Macrophage polarization and iron homeostasis. The M2-like phenotype exhibits high expression of ferroportin-1, the divalent metal transporter-1 (DMT1), and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), thus promoting a state of iron release. On the contrary, the M1-like phenotype promotes intracellular iron retention through the upregulation of ferritin, hepcidin, and the transferrin receptor.

Zhao et al. elegantly demonstrated that the FDA-approved iron oxide nanoparticle, ferumoxytol, synergizes with the TLR3 agonist poly (I:C) in inducing macrophage activation, thereby exerting a potent anti-tumor effect in a melanoma model [36]. Noticeably, the effect observed by these authors comprised cell contact-dependent and -independent molecular cues mostly triggered by ROS burst and phagocytosis of tumor cells in vitro. The synergistic effects of poly (I:C) and ferumoxytol treatment in vivo impaired primary B16F10 tumor growth, and subsequent lung metastasis appearance more efficiently than either treatment alone. This reduction in tumor growth correlated with an increase in pro-inflammatory macrophages within the tumor nest. More recently, Wang et al. demonstrated that ferumoxytol is primarily internalized by macrophages through scavenger receptors, i.e., SRI/II, and not mediated by complement C3b, as these rather large nanoparticles (30 nm) do not exhibit C3b deposition on their surface [37]. Taking another approach, Wang et al. proved that the intracellular TLR9-agonists CpG and ferumoxytol also synergize to promote an M1-like phenotype in macrophages with a tumoricidal capacity [38]. While the results outlined thus far are mainly focused on the synergy between IONPs and TLR agonists, others have demonstrated that the pro-M1/anti-tumor properties of ferumoxytol are intrinsic to the NP. Zanganeh et al. showed that the ferumoxytol-loaded macrophage-like cells, RAW264.7, induce apoptosis in MMTV-PyMT cancer cells mediated by Fenton reactions [39], leading to retardation in tumor growth in vivo. More importantly, intravenous pre-treatment with ferumoxytol protected mouse liver from KP1 tumor-cell infiltration, and this was associated with an M1-like phenotype of infiltrating macrophages and a loss of M2-like features in resident macrophages [39].

While studying the artificial reprogramming of macrophages for cancer cell therapy, Li Chu-Xin et al. found that feeding macrophages with hyaluronic acid-modified iron oxide NPs (HION) or bare iron oxide NPs (ION) triggered consistent production of ROS and pro-inflammatory cytokines [40]. Consequently, both HION-fed and ION-fed macrophages exerted an anti-tumor effect on the murine breast-tumor cell line 4T1 in a cell contact-independent manner by inducing active caspase 3 and inhibiting cell proliferation. The tumor microenvironment is known for its highly immunosuppressive profile, which comprises M2 macrophage populations that sustain tumor growth while hindering a pro-inflammatory shift [41]. This M2 macrophage population is believed to arise from resident macrophages and bone marrow-derived monocytes engaged in M2 programming by tumor cell-derived factors such as IL-10. Therefore, it is desirable that macrophage-based antitumor therapy not only induces an M1 phenotype from naive macrophages but also that it reverses the resident M2 program into an M1 phenotype. In a related study, Chu-Xin et al. found that HION-loading provided M1 macrophages with resistance to M2-inducing factors and triggered M2-to-M1 reversion [40]. The in vivo tumor tropism of HION also provoked a reduction in tumor growth that was most likely due to decreased proliferation and apoptosis rates, thus indicating that this nanoreagent could be used to directly affect tumor cell growth and/or be employed for macrophage reprogramming in the tumor microenvironment.

Given the impact that IONPs can have on macrophage activation, it is only logical to exploit this intrinsic activity to potentiate antigen-specific immune responses by targeting the antigen-presenting capacity of myeloid cells. Based on this reasoning, Luo et al. synthesized PMAO (poly(maleic anhydride-alt-1-octadecene))–PEG-coated ultra-small IONPs, onto which OVA was conjugated covalently, assessing their efficacy as a prophylactic and therapeutic vaccine for malignant melanoma. When used as therapy, subcutaneous injection of IONPs alone in tumor-bearing mice delayed both primary OVA-expressing B16F10 tumor growth and the number of lung metastases; when conjugated with OVA, however, a significantly greater inhibition was observed [42]. Interestingly, while prophylactic injection of OVA alone delayed the appearance of OVA-expressing B16F10 tumors, the use of OVA-PMAO-PEG@IONPs completely inhibited primary tumor growth and the onset of metastatic lung nodules. Therefore, the influence that the variable intrinsic biological activities of IONPs have on macrophage-activation status makes IONPs instrumental for developing combinatorial immunotherapy approaches.

3. IONPs and Dendritic Cells (DC)

Dendritic cells (DCs) are another important cellular target for IONP-based immunomodulatory therapies. They are the primary antigen-presenting cells in the organism and represent the link between the innate immune system, which acts as the first line of defense by detecting external threats, and the adaptive immune system, which responds to the pathogen by mounting immune memory responses of exquisite specificity [43]. In their immature state, DCs scan the microenvironment for danger using pathogen recognition receptors that bind pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [44]. Once an immature DC recognizes a PAMP, it becomes activated and matures into a professional antigen-presenting cell that is capable, among other things, of priming naïve T cells. DCs are therefore critical for mounting potent and durable immune responses to pathogens. DC theragnosis with IONPs thus represent an attractive approach for immunomodulation of antitumor immune responses, although strategies need to take into consideration the activation status of the DC. Indeed, Mou et al. found that while labeling mature DCs with IONPs does not have a significant effect on mature DC behavior, IONP-loaded immature DCs became activated as measured by increased CD80, CD86, and MHC-II expression. IONPs may influence the antigen-presentation function of DCs. On this issue, Shen et al. observed that lactosylated N-alkyl-polyethyleneimine (PEI2k)-IONPs promoted DC maturation through a mechanism involving NP-mediated induction of protective autophagy [45]. Likewise, Liu et al. demonstrated that increasing concentrations of pristine IONPs enhanced OVA cross-presentation in a model of DC. Curiously, the positively charged aminopropyltrimethoxysilane (APTS)-coated IONPs appeared to promote more efficient antigen cross-presentation as compared to the negatively charged IONPs (DMSA-coated IONPs), and this was dependent on TLR-3 [46]. This adjuvant effect of IONPs was also demonstrated by Zhao et al. in an OVA-based vaccine model by administering OVA@IONPs to OVA-expressing CT26 tumor-bearing mice, which produced a significant delay in tumor growth [47]. Zhang et al., however, revealed that PEG-coated IONPs disturbed mitochondrial dynamics through an increase in autophagy, and as a consequence, treated immature DCs exhibited downregulation of co-stimulatory molecules such as CD86, CD80, and CCR7, as well as reduced phagocytic capacity [48]. Therefore, as seen in macrophages, the effects of IONPs on DCs is variable and depends on a plethora of factors such as IONP size, shape, and coating, as well as DC maturation status, among others. Modulation of DC activity through IONP treatment is therefore a promising area of research that will require continued efforts to pinpoint the critical factors influencing IONP–DC interactions.

4. Iron Oxide and Functions of Endothelial Cells

Although myeloid cell interaction with IONPs is essential to understand, design, and improve IONP-based theranostics, endothelial cells (ECs) also impact the efficacy of such approaches, as these cells necessarily interact with IONPs when the nanomaterial migrates to the interstitial and local microenvironment. As major targets of oxidative stress, ECs can engage anti-oxidant mechanisms that protect them from apoptosis. Thus, even in the presence of IONPs acting as ROS-triggering agents, ECs can promote anti-oxidant protective mechanisms. Duan et al. demonstrated that dextran-coated IONPs induced autophagy in human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs), which in turn promoted cell survival. These IONP-treated HUVECs exhibited resistance to H2O2-induced cell death [49]. Likewise, Zhang et al. found that pristine IONPs disturbed autophagy in HUVECs and exacerbated the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNFα [50].

We also showed that polyethyleneimine (PEI)-coated IONPs profoundly alter EC function, which indicated that IONP-based reagents could be designed to modulate angiogenesis. PEI-coated IONPs disturbed the formation of focal adhesions and inhibited cell migration and in vitro tube formation through ROS-associated responses. Consistent with these in vitro effects, in vivo administration of PEI-coated IONPs reduced the number of vessels in a human breast cancer model [51]. ROS also mediates polyglucose sorbitol carboxymethyether (PSC)-coated IONP-triggered induction of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in vascular ECs. Wen et al. observed that PSC-coated IONPs reduced the formation of tubules in vitro, closely resembling what we observed with PEI-coated IONPs; in contrast to our data, however, the authors observed enhanced EC migration [52]. It is therefore likely that the synthetic identity of IONPs also influences the EC response to these nanoreagents. Investigating the clinically relevant contrast agent, Endorem® (dextran-coated IONPs), and custom-made silica@IONPs, Atanina et al. observed that treatment with these nanosystems decreased impedance, and thus integrity, of human microvascular endothelial-cell layers without affecting their viability. The loss of EC layer integrity was accompanied by the appearance of surface intercellular gaps and a decrease in NO production [53]. Altogether, it appears that IONPs mostly impair EC functions, suggesting they could potentially be used as an anti-angiogenic factor. However, just like macrophages, the EC response to IONPs depends greatly on several factors, including synthetic identity. Matuszak et al. proved that lauric acid-coated and BSA-stabilized IONPs are highly internalized by ECs, leading to acute toxicity, while lauric acid/BSA-coated and dextran-coated IONPs exhibited no evident toxicity [54]. The effects of IONPs on EC remains a somewhat underexplored area of knowledge. Given the importance of these cells in modulating immune responses and their presence at the interface between IONPs and the tumor environment, further insight into the intrinsic activity of IONPs on ECs will be of great interest to improve theranostic applications.

5. Tumor Microenvironment and Iron Oxide Nanoparticles

Up to now, we have only discussed the direct implications that IONP loading has on cells of the mononuclear phagocytic system, dendritic cells, and endothelial cells. Nonetheless, when analyzing the tumor microenvironment (TME), we should take into consideration its intrinsic complexity. As a mere reminder, TME is directly linked to a plethora of biological mechanisms that support tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis [55][56]. Processes such as proliferative [57][58], anti-apoptotic [59], pro-angiogenic [60], and immune-suppressive [61] phenomena, as well as mechanisms related to immune-surveillance evasion by tumors [62] greatly depend on the composition and organization of the TME. The niche that comprises the TME is formed by immune and endothelial cells as well as fibroblasts, and all have the potential to interact with IONPs that reach the tumor mass. Therefore, IONPs are expected to exert a biological impact on these cells as well as the tumor cells, which are usually the main targets of IONP-based theranostics. We have demonstrated that PEI-coated IONPs disturbed invadosome formation by the mouse tumor cells Pan02, and, as a consequence, inhibited tumor cell migration and invasion [63]. Moreover, these same PEI-coated IONPs altered macrophage and endothelial-cell activity in vitro and in vivo [51][63], illustrating the feasibility of developing nanoreagents that impair tumor cell biology, modify immune infiltration and alter tumor angiogenesis.

The presence of iron ions can also modulate the activity of the TME. Costa da Silva et al. showed that the presence of iron-loaded macrophages nesting in the invasive margins of non-small lung cell tumors correlated with smaller tumor size [64]. These iron-loaded cells localized near the sites of red blood cell (RBC) extravasation, thus pointing to RBCs as the iron source. More precisely, hemolytic RBCs trigger a TAM polarization toward an M1-like phenotype as measured by mRNA expression of M1 markers (Il6, Nos2, and Tnfa), and increased anti-tumor activity [64]. Costa da Silva et al. also found that cross-linked iron oxide nanoparticles injected intravenously in Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC)-bearing mice accumulated within F4/80 macrophages and reduced tumor growth [64]. These findings are of substantial consequence for IONP-based cancer theragnosis [65] as they indicate that, should IONPs accumulate within TAM in the tumor margins of inner zones, TAMs could revert their phenotype from M2 to M1.

IONPs can also support the anti-tumor effect by enhancing antigen cross-presentation in the tumor niche, as demonstrated by Lee et al. [66]. This enhancement was attributed to a mere increase in antigen delivery to DCs as compared to antigen alone, and not to the intrinsic biological effects of the carriers, SiO2@IONPs, on DC activation status. Thus, the adjuvancy of IONPs was more physical than biological, i.e., facilitating antigen endocytosis [66]. Another study using more complex nanocomposites in which an OVA antigen was covalently attached to IONPs showed a drastic reduction of OVA-expressing B16 tumor-derived lung metastasis in vivo [42]. In this work, IONPs exhibited an anti-tumor effect when injected alone, suggesting they also possess intrinsic biological activity that mitigates tumor growth. Similarly, Zanganeh et al. showed that the FDA-approved IONP, ferumoxytol, displayed in vivo anti-tumor effects in a mouse breast cancer model, effects which were most likely mediated through the induction of pro-inflammatory macrophages in the TME [39]. IONPs can also directly alter tumor biology. The therapeutic value of IONPs, therefore, should not rely solely on the capacity of these nanoparticles to modulate the tumor cell biology, but rather should also take into account their effects on the TME.

6. Conclusion

As part of the antitumor focus taken in the present article, we have seen that IONPs will primarily encounter cells of the mononuclear phagocytic system, dendritic cells, endothelial cells, and tumor cells. The physical, synthetic (coating), and biological identity of IONPs will influence their effects on the biology of the cells they encounter in the organism; conversely, the cell type and programming encountered by these nanoparticles will influence the effects triggered by IONPs. Overall, some common features emerge when assessing the cellular effects of IONPs: IONPs can (1) alter iron metabolism, (2) promote ROS production, and (3) likely induce autophagic machinery upon internalization. These complex interactions between the nanomaterial identities and the extra- and intra-cellular environment will ultimately define the intrinsic biological identity of IONPs. Understanding these interactions will, in turn, allow for the development of more rational combinatorial nanoreagents for theranostics.

References

- Marina Dukhinova; Artur. Y. Prilepskii; Alexander A. Shtil; Vladimir V. Vinogradov; Metal Oxide Nanoparticles in Therapeutic Regulation of Macrophage Functions. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1631, 10.3390/nano9111631.

- Stefania Recalcati; Massimo Locati; Gaetano Cairo; Systemic and cellular consequences of macrophage control of iron metabolism. Seminars in Immunology 2012, 24, 393-398, 10.1016/j.smim.2013.01.001.

- Gaetano Cairo; Stefania Recalcati; Alberto Mantovani; Massimo Locati; Iron trafficking and metabolism in macrophages: contribution to the polarized phenotype. Trends in Immunology 2011, 32, 241-247, 10.1016/j.it.2011.03.007.

- Tomas Ganz; Elizabeta Nemeth; Iron homeostasis in host defence and inflammation. Nature Reviews Immunology 2015, 15, 500-510, 10.1038/nri3863.

- Nyamdelger Sukhbaatar; Thomas Weichhart; Iron Regulation: Macrophages in Control. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 137, 10.3390/ph11040137.

- Tomas Ganz; Hepcidin, a key regulator of iron metabolism and mediator of anemia of inflammation. Blood 2003, 102, 783-788, 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0672.

- Stefania Recalcati; Elena Gammella; Gaetano Cairo; Ironing out Macrophage Immunometabolism.. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 94, 10.3390/ph12020094.

- Stefania Recalcati; Massimo Locati; Agnese Marini; Paolo Santambrogio; Federica Zaninotto; Maria De Pizzol; Luca Zammataro; Domenico Girelli; Gaetano Cairo; Differential regulation of iron homeostasis during human macrophage polarized activation. European Journal of Immunology 2010, 40, 824-835, 10.1002/eji.200939889.

- Yun Zhou; Ke-Ting Que; Zhen Zhang; Zu J. Yi; Ping X. Zhao; Yu You; Jian-Ping Gong; Zuo-Jin Liu; Iron overloaded polarizes macrophage to proinflammation phenotype through ROS/acetyl‐p53 pathway. Cancer Medicine 2018, 7, 4012-4022, 10.1002/cam4.1670.

- Rafiou Agoro; Meriem Taleb; Valerie F. J. Quesniaux; Catherine Mura; Cell iron status influences macrophage polarization. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0196921, 10.1371/journal.pone.0196921.

- Alessia Pagani; Antonella Nai; Gianfranca Corna; Lidia Bosurgi; Patrizia Rovere-Querini; Clara Camaschella; Laura Silvestri; Low hepcidin accounts for the proinflammatory status associated with iron deficiency. Blood 2011, 118, 736-746, 10.1182/blood-2011-02-337212.

- Konrad Hoeft; Donald Bloch; Jan A. Graw; Rajeev Malhotra; Fumito Ichinose; Aranya Bagchi; Iron Loading Exaggerates the Inflammatory Response to the Toll-like Receptor 4 Ligand Lipopolysaccharide by Altering Mitochondrial Homeostasis. Anesthesiology 2017, 127, 121-135, 10.1097/aln.0000000000001653.

- Anca Sindrilaru; Thorsten Peters; Stefan Wieschalka; Corina Baican; Adrian Băican; Henriette Peter; Adelheid Hainzl; Susanne Schatz; Yu Qi; Andrea Schlecht; et al.Johannes M. WeissMeinhard WlaschekCord SunderkötterKarin Scharffetter‐Kochanek An unrestrained proinflammatory M1 macrophage population induced by iron impairs wound healing in humans and mice.. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2011, 121, 985-97, 10.1172/JCI44490.

- Antje Kroner; Andrew D. Greenhalgh; Juan G. Zarruk; Rosmarini Passos Dos Santos; Matthias Gaestel; Samuel David; TNF and Increased Intracellular Iron Alter Macrophage Polarization to a Detrimental M1 Phenotype in the Injured Spinal Cord. Neuron 2015, 86, 1317, 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.05.029.

- Bastien Dalzon; Anaëlle Torres; Solveig Reymond; Benoit Gallet; François Saint-Antonin; Véronique Collin-Faure; Christine Moriscot; Daphna Fenel; Guy Schoehn; Catherine Aude-Garcia; et al.Thierry Rabilloud Influences of Nanoparticles Characteristics on the Cellular Responses: The Example of Iron Oxide and Macrophages. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 266, 10.3390/nano10020266.

- Jin Cheng; Qian Zhang; Sisi Fan; Amin Zhang; Bin Liu; Yuping Hong; Jinghui Guo; Da-Xiang Cui; Jie Song; The vacuolization of macrophages induced by large amounts of inorganic nanoparticle uptake to enhance the immune response. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 22849-22859, 10.1039/c9nr08261a.

- Yujun Xu; Yi Li; Xinghan Liu; Yuchen Pan; Zhiheng Sun; Yaxian Xue; Tingting Wang; Huan Dou; Yayi Hou; SPIONs enhances IL-10-producing macrophages to relieve sepsis via Cav1-Notch1/HES1-mediated autophagy.. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 6779-6797, 10.2147/IJN.S215055.

- Luisa Pedro; Quentin Harmer; Eric Mayes; Jacqueline D. Shields; Impact of Locally Administered Carboxydextran-Coated Super-Paramagnetic Iron Nanoparticles on Cellular Immune Function.. Small 2019, 15, e1900224-e1900224, 10.1002/smll.201900224.

- Klára Jiráková; Maksym Moskvin; Lucia Machová Urdzíková; Pavel Rössner; Fatima Elzeinová; Milada Chudíčková; Daniel Jirák; Natalia Ziolkowska; Daniel Horák; Šárka Kubinová; et al.Pavla Jendelova The negative effect of magnetic nanoparticles with ascorbic acid on peritoneal macrophages. Neurochemical Research 2019, 45, 159-170, 10.1007/s11064-019-02790-9.

- Rongrong Jin; Li Liu; Wencheng Zhu; Danyang Li; Li Yang; Jimei Duan; Zhongyuan Cai; Yu Nie; Yunjiao Zhang; Qiyong Gong; et al.Bin SongLongping WenJames M. AndersonHua Ai Iron oxide nanoparticles promote macrophage autophagy and inflammatory response through activation of toll-like Receptor-4 signaling.. Biomaterials 2019, 203, 23-30, 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.02.026.

- Ling Zhang; Shengwei Tan; Yingxun Liu; Hongmei Xie; Binhua Luo; Jinke Wang; In vitro inhibition of tumor growth by low-dose iron oxide nanoparticles activating macrophages. Journal of Biomaterials Applications 2019, 33, 935-945, 10.1177/0885328218817939.

- Vladimir Mulens-Arias; José Manuel Rojas; Sonia Pérez-Yagüe; Maria P. Morales; Domingo F. Barber; Polyethylenimine-coated SPIONs trigger macrophage activation through TLR-4 signaling and ROS production and modulate podosome dynamics. Biomaterials 2015, 52, 494-506, 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.02.068.

- Liu Liu; Rui Sha; Lijiao Yang; Xiaomin Zhao; Yangyang Zhu; Jinhao Gao; Yunjiao Zhang; Long-Ping Wen; Impact of Morphology on Iron Oxide Nanoparticles-Induced Inflammasome Activation in Macrophages. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2018, 10, 41197-41206, 10.1021/acsami.8b17474.

- Shuzhen Chen; Suyun Chen; Yun Zeng; Lin Lin; Chuang Wu; Yanyan Ke; Gang Liu; Size-dependent superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles dictate interleukin-1β release from mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages. Journal of Applied Toxicology 2018, 38, 978-986, 10.1002/jat.3606.

- Zhengying Gu; Tianqing Liu; Jie Tang; Yannan Yang; Hao Song; Zewen K. Tuong; Jianye Fu; Chengzhong Yu; Mechanism of Iron Oxide-Induced Macrophage Activation: The Impact of Composition and the Underlying Signaling Pathway. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2019, 141, 6122-6126, 10.1021/jacs.8b10904.

- José Manuel Rojas; Laura Sanz-Ortega; Vladimir Mulens-Arias; Lucia Gutierrez; Sonia Pérez-Yagüe; Domingo F. Barber; Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle uptake alters M2 macrophage phenotype, iron metabolism, migration and invasion. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine 2016, 12, 1127-1138, 10.1016/j.nano.2015.11.020.

- Xiaoyan Liu; Jozsef Gal; Haining Zhu; Sequestosome 1/p62: a multi-domain protein with multi-faceted functions. Frontiers in Biology 2012, 7, 189-201, 10.1007/s11515-012-1217-z.

- M. Lamar Seibenhener; Jeganathan Ramesh Babu; Thangiah Geetha; Hing C. Wong; N. Rama Krishna; Marie W. Wooten; Sequestosome 1/p62 Is a Polyubiquitin Chain Binding Protein Involved in Ubiquitin Proteasome Degradation. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2004, 24, 8055-8068, 10.1128/mcb.24.18.8055-8068.2004.

- Hua Yang; Hong-Min Ni; Fengli Guo; Yifeng Ding; Ying-Hong Shi; Pooja Lahiri; Leopold F. Fröhlich; Thomas Rülicke; Claudia Smole; Volker C. Schmidt; et al.Kurt ZatloukalYue CuiMasaaki KomatsuJia FanWen-Xing Ding Sequestosome 1/p62 Protein Is Associated with Autophagic Removal of Excess Hepatic Endoplasmic Reticulum in Mice*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2016, 291, 18663-18674, 10.1074/jbc.M116.739821.

- Manuela Giraldo Villegas; Melissa Trejos Ceballos; Jeaneth Urquijo; Elen Yojana Torres; Blanca Lucía Ortiz-Reyes; Mauricio Rojas López; Oscar Luis Arnache-Olmos; Poly(acrylic acid)-Coated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles interact with mononuclear phagocytes and decrease platelet aggregation. Cellular Immunology 2019, 338, 51-62, 10.1016/j.cellimm.2019.03.005.

- Bastien Dalzon; Mélanie Guidetti; Denis Testemale; Solveig Reymond; Olivier Proux; Julien Vollaire; Véronique Collin-Faure; Isabelle Testard; Daphna Fenel; Guy Schoehn; et al.Josiane ArnaudMarie CarriereVéronique JosserandThierry RabilloudCatherine Aude-Garcia Utility of macrophages in an antitumor strategy based on the vectorization of iron oxide nanoparticles.. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 9341-9352, 10.1039/c8nr03364a.

- Yujun Xu; Yaxian Xue; Xinghan Liu; Yi Li; Hua-Ping Liang; Huan Dou; Yayi Hou; Ferumoxytol Attenuates the Function of MDSCs to Ameliorate LPS-Induced Immunosuppression in Sepsis.. Nanoscale Research Letters 2019, 14, 379-11, 10.1186/s11671-019-3209-2.

- Runze Yang; Susobhan Sarkar; Daniel Korchinski; Ying Wu; V. Wee Yong; Jeff F. Dunn; MRI monitoring of monocytes to detect immune stimulating treatment response in brain tumor. Neuro-Oncology 2016, 19, 364-371, 10.1093/neuonc/now180.

- Lin Gao; Lisi Xie; Xiaojing Long; Zhiyong Wang; Cheng-Yi He; Zhi-Ying Chen; Lei Zhang; Xiang Nan; Hulong Lei; Xin Liu; et al.Gang LiuJian LuBensheng Qiu Efficacy of MRI visible iron oxide nanoparticles in delivering minicircle DNA into liver via intrabiliary infusion. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 3688-3696, 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.094.

- Chiara Zini; Mary Anna Venneri; Selenia Miglietta; Damiano Caruso; Natale Porta; A. M. Isidori; Daniela Fiore; Daniele Gianfrilli; Vincenzo Petrozza; Andrea Laghi; et al. USPIO-labeling in M1 and M2-polarized macrophages: An in vitro study using a clinical magnetic resonance scanner. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2018, 233, 5823-5828, 10.1002/jcp.26360.

- Jiaojiao Zhao; Zhengkui Zhang; Yaxian Xue; Guoqun Wang; Yuan Cheng; Yuchen Pan; Shuli Zhao; Yayi Hou; Anti-tumor macrophages activated by ferumoxytol combined or surface-functionalized with the TLR3 agonist poly (I : C) promote melanoma regression. Theranostics 2018, 8, 6307-6321, 10.7150/thno.29746.

- Guankui Wang; Natalie J. Serkova; Ernest V. Groman; Robert I. Scheinman; Dmitri Simberg; Feraheme (Ferumoxytol) Is Recognized by Proinflammatory and Anti-inflammatory Macrophages via Scavenger Receptor Type AI/II. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2019, 16, 4274-4281, 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b00632.

- Guoqun Wang; Jiaojiao Zhao; Meiling Zhang; Qian Wang; Bo Chen; Yayi Hou; Kaihua Lu; Ferumoxytol and CpG oligodeoxynucleotide 2395 synergistically enhance antitumor activity of macrophages against NSCLC with EGFRL858R/T790M mutation.. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 4503-4515, 10.2147/IJN.S193583.

- Saeid Zanganeh; Gregor Hutter; Ryan Spitler; Olga Lenkov; Morteza Mahmoudi; Aubie Shaw; Jukka Sakari Pajarinen; Hossein Nejadnik; Stuart Goodman; Michael Moseley; et al.Lisa Marie CoussensHeike E. Daldrup-Link Iron oxide nanoparticles inhibit tumour growth by inducing pro-inflammatory macrophage polarization in tumour tissues. Nature Nanotechnology 2016, 11, 986-994, 10.1038/nnano.2016.168.

- Chu-Xin Li; Yu Zhang; Xue Dong; Lu Zhang; Miao-Deng Liu; Bin Li; Ming-Kang Zhang; Jun Feng; Xian-Zheng Zhang; Artificially Reprogrammed Macrophages as Tumor‐Tropic Immunosuppression‐Resistant Biologics to Realize Therapeutics Production and Immune Activation. Advanced Materials 2019, 31, e1807211, 10.1002/adma.201807211.

- Ning-Bo Hao; Mu-Han Lü; Ya-Han Fan; Ya-Ling Cao; Zhi-Ren Zhang; Shi-Ming Yang; Macrophages in Tumor Microenvironments and the Progression of Tumors. Journal of Immunology Research 2012, 2012, 1, https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/948098.

- Lijia Luo; Muhammad Zubair Iqbal; Chuang Liu; Jie Xing; Ozioma Udochukwu Akakuru; Qianlan Fang; Zihou Li; Yunlu Dai; Aiguo Li; Yong Guan; et al.Aiguo Wu Engineered nano-immunopotentiators efficiently promote cancer immunotherapy for inhibiting and preventing lung metastasis of melanoma.. Biomaterials 2019, 223, 119464, 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119464.

- Stefanie K. Wculek; Francisco J. Cueto; Adriana M. Mujal; Ignacio Melero; Matthew F. Krummel; David Sancho; Dendritic cells in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nature Review Immunology 2020, 20, 7-24, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-019-0210-z.

- Mikayla R. Thompson; John J. Kaminski; Evelyn A. Kurt-Jones; Katherine A. Fitzgerald; Pattern Recognition Receptors and the Innate Immune Response to Viral Infection. Viruses 2011, 3, 920-940, 10.3390/v3060920.

- Taipeng Shen; Wencheng Zhu; Li Yang; Li Liu; Rongrong Jin; Jimei Duan; James M Anderson; Hua Ai; Lactosylated N-Alkyl polyethylenimine coated iron oxide nanoparticles induced autophagy in mouse dendritic cells. Regenerative Biomaterials 2018, 5, 141-149, 10.1093/rb/rbx032.

- Hui Liu; Heng Dong; Na Zhou; Shiling Dong; Lin Chen; Yanxiang Zhu; Hong-Ming Hu; Yongbin Mou; SPIO Enhance the Cross-Presentation and Migration of DCs and Anionic SPIO Influence the Nanoadjuvant Effects Related to Interleukin-1β. Nanoscale Research Letters 2018, 13, 409, 10.1186/s11671-018-2802-0.

- Yi Zhao; Xiaotian Zhao; Yuan Cheng; Xiaoshuang Guo; Wei-En Yuan; Iron Oxide Nanoparticles-Based Vaccine Delivery for Cancer Treatment. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2018, 15, 1791-1799, 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b01103.

- Tian-Guang Zhang; Yu-Long Zhang; Qian-Qian Zhou; Xiao-Hui Wang; Lin-Sheng Zhan; Impairment of mitochondrial dynamics involved in iron oxide nanoparticle‐induced dysfunction of dendritic cells was alleviated by autophagy inhibitor 3‐methyladenine. Journal of Applied Toxicology 2020, 40, 631-642, 10.1002/jat.3933.

- Jimei Duan; Jiuju Du; Rongrong Jin; Wencheng Zhu; Li Liu; Li Yang; Mengye Li; Qiyong Gong; Bin Song; James M Anderson; et al.Hua Ai Iron oxide nanoparticles promote vascular endothelial cells survival from oxidative stress by enhancement of autophagy.. Regenerative Biomaterials 2019, 6, 221-229, 10.1093/rb/rbz024.

- Lu Zhang; Xueqin Wang; Yiming Miao; Zhiqiang Chen; Pengfei Qiang; Liuqing Cui; Hongjuan Jing; Yuqi Guo; Magnetic ferroferric oxide nanoparticles induce vascular endothelial cell dysfunction and inflammation by disturbing autophagy. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2016, 304, 186-195, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.10.041.

- Vladimir Mulens-Arias; José Manuel Rojas; Laura Sanz-Ortega; Yadileiny Portilla; Sonia Pérez-Yagüe; Domingo F. Barber; Polyethylenimine-coated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles impair in vitro and in vivo angiogenesis. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine 2019, 21, 102063, 10.1016/j.nano.2019.102063.

- Tao Wen; Lifan Du; Bo Chen; Doudou Yan; Aiyun Yang; Jian Liu; Ning Gu; Jie Meng; Haiyan Xu; Iron oxide nanoparticles induce reversible endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in vascular endothelial cells at acutely non-cytotoxic concentrations.. Particle and Fibre Toxicology 2019, 16, 30, 10.1186/s12989-019-0314-4.

- Ksenia Astanina; Yvette Simon; Christian Cavelius; Sandra Petry; Annette Kraegeloh; Alexandra K. Kiemer; Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles impair endothelial integrity and inhibit nitric oxide production. Acta Biomaterialia 2014, 10, 4896-4911, 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.07.027.

- Jasmin Matuszak; Philipp Dörfler; Jan Zaloga; Harald Unterweger; Stefan Lyer; Barbara Dietel; Christoph Alexiou; Iwona Cicha; Shell matters: Magnetic targeting of SPIONs and in vitro effects on endothelial and monocytic cell function. Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation 2015, 61, 259-277, 10.3233/ch-151998.

- Shuli Xia; Bachchu Lal; Brian Tung; Shervin Wang; C. Rory Goodwin; John Laterra; Tumor microenvironment tenascin-C promotes glioblastoma invasion and negatively regulates tumor proliferation.. Neuro-Oncology 2015, 18, 507-17, 10.1093/neuonc/nov171.

- J-J Wang; K-F Lei; F Han; Tumor Microenvironment: Recent Advances in Various Cancer Treatments. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2018, 22 (12), 3855-3864, 10.26355/eurrev_201806_15270.

- Yao Yuan; Yu-Chen Jiang; Chongkui Sun; Qianming Chen; Role of the tumor microenvironment in tumor progression and the clinical applications (Review). Oncology Reports 2016, 35, 2499-2515, 10.3892/or.2016.4660.

- Theerawut Chanmee; Pawared Ontong; Naoki Itano; Hyaluronan: A modulator of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Letters 2016, 375, 20-30, 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.031.

- Andrej Lissat; Mandy Joerschke; Dheeraj A. Shinde; T. Braunschweig; Angelina Meier; Anna Makowska; Rachel Bortnick; P. Henneke; Georg W. Herget; Thomas Gorr; et al.Udo Kontny IL6 secreted by Ewing sarcoma tumor microenvironment confers anti-apoptotic and cell-disseminating paracrine responses in Ewing sarcoma cells.. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 552, 10.1186/s12885-015-1564-7.

- Alberto Passi; Davide Vigetti; Simone Buraschi; Renato V. Iozzo; Dissecting the role of hyaluronan synthases in the tumor microenvironment. The FEBS Journal 2019, 286, 2937-2949, 10.1111/febs.14847.

- Torsten Hartwig; Antonella Montinaro; Silvia Von Karstedt; Alexandra Sevko; Silvia Surinova; Ankur Chakravarthy; Lucia Taraborrelli; Peter Draber; Elodie Lafont; Frederick Arce Vargas; et al.Mona A. El-BahrawySergio A. QuezadaHenning Walczak The TRAIL-Induced Cancer Secretome Promotes a Tumor-Supportive Immune Microenvironment via CCR2.. Molecular Cell 2017, 65, 730-742.e5, 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.021.

- Marco Tucci; Anna Passarelli; Francesco Mannavola; Claudia Felici; Luigia Stefania Stucci; Mauro Cives; Francesco Silvestris; Immune System Evasion as Hallmark of Melanoma Progression: The Role of Dendritic Cells. Frontiers in Oncology 2019, 9, 1148, 10.3389/fonc.2019.01148.

- Vladimir Mulens-Arias; José Manuel Rojas; Sonia Pérez-Yagüe; M. Puerto Morales; Domingo F. Barber; Polyethylenimine-coated SPION exhibits potential intrinsic anti-metastatic properties inhibiting migration and invasion of pancreatic tumor cells. Journal of Controlled Release 2015, 216, 78-92, 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.08.009.

- Milene Costa Da Silva; Michael O. Breckwoldt; Francesca Vinchi; Margareta P. Correia; Ana Stojanovic; Carl Maximilian Thielmann; Michael Meister; Thomas Muley; Arne Warth; Michael Platten; et al.Matthias W. HentzeAdelheid CerwenkaMartina U. Muckenthaler Iron Induces Anti-tumor Activity in Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Frontiers in Immunology 2017, 8, 1479, 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01479.

- Derek Reichel; Manisha Tripathi; J. Manuel Perez; Biological Effects of Nanoparticles on Macrophage Polarization in the Tumor Microenvironment. Nanotheranostics 2019, 3, 66-88, 10.7150/ntno.30052.

- Sung-Ju Lee; Jong-Jin Kim; Kyung-Yun Kang; Man-Jeong Paik; Gwang Lee; Sung-Tae Yee; Enhanced anti-tumor immunotherapy by silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles conjugated with ovalbumin.. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 8235-8249, 10.2147/IJN.S194352.