| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tiziana Cappello | + 3590 word(s) | 3590 | 2021-02-22 07:46:15 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 3590 | 2021-03-12 02:59:28 | | |

Video Upload Options

Advancement in the field of nanotechnology has prompted the need to elucidate the deleterious effects of nanoparticles (NPs) on reproductive health. Many studies have reported on the health safety issues related to NPs by investigating their exposure routes, deposition and toxic effects on different primary and secondary organs but few studies have focused on NPs’ deposition in reproductive organs. Noteworthy, even fewer studies have dealt with the toxic effects of NPs on reproductive indices and sperm parameters (i.e. sperm number, motility and morphology) by evaluating, for instance, the histopathology of seminiferous tubules and testosterone levels. To date, the research suggests that NPs can easily cross the blood testes barrier and, after accumulation in the testis, induce adverse effects on spermatogenesis.

1. Introduction

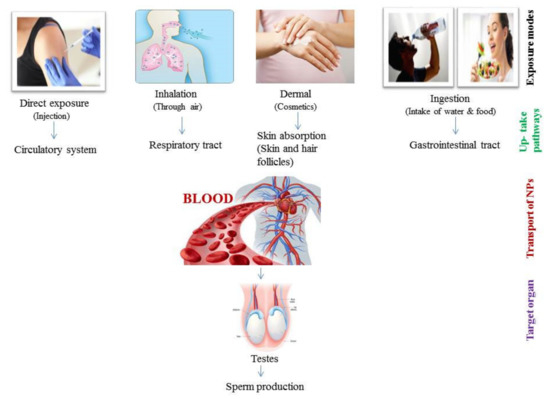

Nanoparticles (NPs) are defined as particles having size less than 100 nm [1] and these particles can be 0D, 1D, 2D and 3D on the bases of their overall shape [2]. The importance of nano sized particles was enhanced when researchers found that size can alter the properties of a substance [1]. NPs are extensively used in industrial and biomedical sectors [3]. It is reported that there are more than 1814 products including textiles, antibiotics, sport and food items in which nano-sized particles are used and this number of products is rapidly increasing [3]. The immense growth in the advanced field of nanotechnologies with all its far reaching benefits has drawn the attention of researchers towards the health risks induced by NPs [4]. Throughout evolution, humans have been exposed to various airborne NPs but intensity of exposure is now significantly increased due to the diverse use of nanoparticles in products in our daily life [5]. This higher production rate of NPs also poses risks because of their release into the environment as nano structural materials that may exert their toxic impact on the ecosystem [6][7]. The hazard of NPs is directly or indirectly associated with the consumers that are exposed to these nanomaterials and their harmful effects during their usage [8]. In fact, NPs interact with the human body via ingestion through food, injection, penetration through skin and inhalation [9]. This uptake of NPs can be non-intentional (i.e., by inhalation, transdermal) and intentional (i.e., by injection, food additives, ingredients and supplements containing NPs) [10]. NPs then penetrate into body organs through the blood circulatory system [11] and interact with biological systems leading to intense cytotoxicity [12][13][14][15][16] due to their nano-size [17].

The ability of different chemicals to penetrate the cell is a matter of concern with regard to reproductive toxicity due to the complex biological processes that can be affected by these compounds through environmental exposure [18]. Reproductive toxicity is now considered as an important issue to be investigated in overall toxicology [10]. Fertility and successful reproduction are of vital importance to sustain a species and there is an increased need of public awareness because of NPs’ induced reproductive toxicity, since production of engineered nanoparticles might increase the risk of interference with the reproductive system [19]. The male reproductive system is considered sensitive to oxidative stress and inflammation [20][21][22], and both can be used as hallmarks for the exposure to NPs [20]. Oxidative stress is a major contributing factor to reproductive toxicity due to NPs [23]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) is the key factor in inducing 30–80% of infertility issues in men [24], as the increased production of ROS leads to cell apoptosis and impaired spermatogenesis [25]. Several studies have reported NPs’ induced oxidative stress in male reproductive organs after the exposure to different nanoparticles such as Ag NPs [26][27], co-exposure of TiO2 NPs and ZnO NPs [28], Cu NPs [29] and Ni NPs [30]. Epidemiologists have taken a keen interest regarding these reproductive health issues because in some areas young males demonstrate a suboptimal quality and number of spermatozoa [31][32][33]. In recent years, sperm quality and numbers have been reduced in humans and in many cases the reason behind this is still unknown [34]. According to previous studies, NPs may affect spermatogenesis because of their presence in the environment, and those people who are mostly exposed to NPs are at major risk [34]. However, nanoparticles are not all involved in inducing adverse effects. In fact, Shi et al. [35] described that nano-selenium used as a supplement positively enhanced the quality of goat spermatozoa. Therefore, some nanoparticles showed nontoxic and beneficial effects on spermatogenesis. However, the route, dose, size and characteristics of NPs play vital roles in determining their impact on male germ cells [36]. NPs have the ability to cross the blood-testis barrier which increases the concern about biocompatibility and NP distribution [37].

2. Path of NPs into the Reproductive System

Reproductive medicine is a developing field aimed at improving the chances of safe conception and the delivering of healthy babies [38]. Many studies have reported on the use of nanomaterials in detection and targeted therapy related to reproductive cancers [39]. For instance, aptamere-conjugated gold NPs and super-paramagnetic iron oxide NPs are commonly used for the treatment of prostate cancer patients [40][41][42], and also to determine the expression of genes in offspring [42][43][44].

Despite the wide use of NPs in clinical application and reproductive medicine, NPs have the potential to accumulate in tissues and organs, resulting in consequent long-term carcinogenic effects [45]. According to Taylor et al. [46], the accumulation of NPs in somatic cells induces inflammation leading to carcinogenesis, whereas the accumulation of NPs in reproductive cells disturbs the fertility and affects the development of offspring. In drug delivery, penetration of NPs into target cells is important. Use of gold NPs has caused detrimental effects on sperm morphology, motility and DNA of mammalian sperm cells [46][47][48][49].

Metal and metal oxide NPs are widely used in cosmetology and dermatology. NPs are used for dermatological treatments, for skin care and in diagnostic imaging of skin diseases [50]. Sub-dermal exposure of Ag NPs for 7 and 28 days in male rats showed alterations in sperm number and motility as well as in testosterone (T), luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels along with histological abnormalities in the testis [51]. In some studies, it is reported that NPs cannot penetrate the skin, while in others penetration of metallic NPs, including iron NPs, is confirmed through hair follicles [52]. This depends on NP size since it has been documented that NPs with 4 nm size can easily penetrate the skin but NPs 45 nm in size can only enter through damaged skin [53]. Rancan et al. [54] also checked the penetration of various sizes of SiO2 NPs (291 ± 9 to 42 ± 3 nm) through the skin and found that it was mostly nano-sized particles that showed penetration through damaged stratum cornum. In dermal exposure, NPs can only enter into the epidermis through hair follicles and damaged skin (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of various routes of nano-particles (NPs) in testes.

Gastrointestinal (GI) exposure of NPs through ingestion is an important absorption pathway. NPs can be absorbed in the GI tract and then enter into the blood, therefore easily reaching the secondary organs and accumulating there (Figure 1) [55]. NPs indirectly enter the body through ingestion as humans take food additives, ingredients and supplements that contain different types of NP [56]. In the food industry, the addition of NPs to various products is increasing, and the most commonly used NPs in food products are ZnO NPs, TiO2 NPs, SiO2 NPs, and Ag NPs [3]. As a matter of fact, the oral ingestion of different NPs in humans has notably increased in the last decade. Intragastric exposure of TiO2 NPs induced immunological dysfunction in mouse testis [57]. Moreover, oral administration of Ag NPs induced reduction in sperm number of male Wistar rats [58][59]. Through ingestion, the daily consumed ranges for various NPs are different. For instance, the daily consumed SiO2 NPs is around 126 mg/kg/day for a person with body weight 70 kg [60], though the accepted limit by the European Food Authority for SiO2 NPs is 20–50 mg/kg/day for a 60 kg person [61]. Daily ingestion values of Ag NPs and TiO2 NPs are around 0.008–0.032 µg/mL and 0.12–12.6 µg/mL, respectively [62]. It is also important to notice that different NPs are characterized by different toxic levels as, for example, TiO2 NPs and SiO2 NPs are less genotoxic than Ag NPs with the same size range [63].

NPs exposure through inhalation is another important route of exposure through the environment that induces damage to the fetal organs. Inhalation of NPs is linked with molecular alterations in the developmental process and induces deleterious effects on offspring [64]. The ability of NPs to penetrate through the respiratory tract depends upon their size [65][66]. The endocrine activity of the male reproductive system was also disturbed after the exposure to NPs via rich diesel exhaust through inhalation in adult male rats [67]. It was also reported that inhalation of NPs affects the reproductive system of male offspring, including reduced sperm number in F1 males after carbon black NPs exposure [68][69].

Overall, it is known that mononuclear phagocytic cells take up NPs, and in this way NPs enter cells [70]. Absorbance of NPs through dermal, ingestion and inhalation exposure enables nanoparticles to reach the circulatory system and then be translocated to many body tissues and organs, until their accumulation into the reproductive organs (Figure 1) [71], and even into the fetus [72].

Because of their nano size, NPs have the ability to penetrate the biological barriers such as the blood testes barrier (BTB) [34] that provides protection to the reproductive tissues [73]. Therefore, the crossing of NPs induces toxic effects on spermatogenesis [74]. After NP exposure, via different routes, NPs reach the reproductive system, where the main target areas of NPs in males are the epididymis and testis [75]. Sundarraj et al. [76] observed the accumulation of NPs in the testis of mice after iron oxide NP (25 and 50 mg/kg) exposure, documenting the ability of these NPs to cross the BTB and accumulate in the testicular tissue as demonstrated by the presence of iron content. Oral administration of fluorescent europium doped ZnO NPs to mice for 14 days showed their accumulation in testes, indicating the penetration of these NPs through the BTB [77]. Similarly, after intragastric administration of TiO2 NPs at the concentration of 2.5, 5 and 10 mg/kg BW in male mice for 90 days, it was observed that NPs crossed the BTB, reached the testes and then accumulated, inducing testicular toxicity resulting in poor quality of sperm, changes in hormone level and testicular lesions [78]. In other studies, contrasting results were reported. For instance, an intramuscular administration of gold core silica shell NPs with 70 nm size in mice showed absence of particles reaching the testes [79]. Similarly, intravenous administration of TiO2 NPs at the concentration of 0.1, 1, 2 and 10 mg/kg BW (1 dose/week) for 4 weeks highlighted the accumulation of Ti in the liver but not in the testes of mice [80]. Interestingly, the injection in male mice of Ag NPs with 25 nm size for 4 months via intraperitoneal and intravenous routes, with the aim of investigating the biological fate and potential toxicity of Ag NPs, showed that these NPs were able to cross the BTB and then localize at the testes [81]. Accumulation of Ag NPs was also observed in the basement membrane of testes after oral exposure in male Wistar rats at a dose of 20 µg/kg/day [82]. Zhou et al. [83] also reported the accumulation of Pb Se-NPs in a size dependent manner in male Sprague Dawley rats after intraperitoneal administration at a dose of 10 mg/kg/week that confirmed the transfer of NPs through the BTB.

3. Adverse Effects of NPs on the Reproductive System

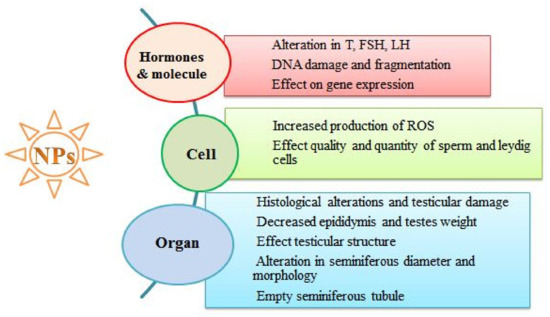

After entering the reproductive system, NPs may induce different deleterious effects at the reproductive organ, cell and hormone levels, as clearly depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Exposure to NPs and their reproductive toxic effects at various biological levels.

3.1. Adverse Effects of NPs on Reproductive Organ Weight

After crossing the BTB, NPs reach and accumulate in the reproductive organs, inducing further toxic damage. It is reported that any change in body and organ weight indicates the toxicity induced by chemical exposure [84]. As a matter of fact, the exposure of Ni NPs in healthy adult rats caused reduction in body weight when at various concentrations (5, 15, 45 mg/kg BW), while epididymis to body weight ratio increased in a dose dependent manner [85]. Conversely, no change in body and organ weight was observed after oral exposure to Ag NPs (60 nm) at dose of 15 and 50 µg/kg BW in male Wistar rats [59]. Intravenous administration of Ag NPs (20 nm) at concentrations of 5 and 10 mg/kg BW also induced no alteration in male Wistar rats [86]. A very recent study demonstrated that nanosized Ag NPs caused toxic effects on the reproductive system of male rats. Reduction in body weight was indeed observed after sub-dermal exposure of Ag NPs in male rats when administered at a dose of 50 mg/kg BW for 28 days, whereas decrease in the relative weight of testes and epididymis was found with the same dose exposure for 7 days [51]. Therefore, it is evident that NPs’ impact on body and organ weight is dose and time dependent. Oral administration of ZnO NPs (50, 150, 450 mg/kg) in male mice for 14 days significantly reduced the body weight and increased the relative testicular weight in a dose dependent manner, while the relative epididymis weight was greater at 50 and 450 mg/kg than at a dose of 150 mg/kg ZnO NPs [87]. Hence, different NPs behave differently.

3.2. Adverse Effects of NPs on Seminiferous Tubules

The seminiferous tubule is the site for spermatogenesis, and during this process the DNA of spermatogenic cells may be damaged due to ROS production [88]. Exposure to NPs induces histological changes in seminiferous tubules of testicular tissues, leading to testicular injury and reduced sperm production. Intraperitoneal exposure of iron oxide NPs in mice at concentrations of 25 and 50 mg/kg once a week for 4 weeks caused histopathological changes such as sloughing and detachment of germ cells and vacuolization in seminiferous tubules of testicular tissues [76]. Similar intraperitoneal injection of titanium dioxide nanoparticles induced significant increases in the thickness of interstitial spaces, congestion of blood vessels, and detachment of the germinal epithelium from the basement membrane in the seminiferous tubules of adult male albino rats [89]. Indeed, it is well documented that the exposure of NPs, alone as well as in combination with other NPs, induces toxic histological changes in reproductive organs. Distortion in seminiferous tubules and wide spaces among interstitial cells were observed in male rats after exposure to Al2O3 NPs, while irregularity in the seminiferous tubule shape, empty lumina and reduced thickness of the epithelium lining were observed after exposure to ZnO NPs. Co-administration of Al2O3 NPs and ZnO NPs induced severe damage both in the seminiferous tubules and basement membrane [90]. The intensity of NP induced toxicity depends also on the dose and time exposure. For instance, exposure to Ag NPs at low and high doses for 7 days induced congestion of blood vessels, detachment of the germinal epithelium and distortion in seminiferous tubules in adult albino rats, but when the exposure duration increased to 28 days a significant reduction in the germinal epithelium and absence of spermatozoa in shrunk seminiferous tubules were observed [91] (Table 1). Dose dependent histological degenerative changes were observed in testicular tissue of adult rats after exposure to Ag NPs at low (2 mg/kg BW) and high (4 mg/kg BW) doses. At low dose, vacuolation in the seminiferous tubule was observed along with reduced number of spermatogenic cell lines, while at high doses of Ag NPs this number was significantly reduced and vacuolation in germinal epithelial cells was particularly noticed, in combination with basement membrane damage and detachment from the surrounding tubules, severe congestion in blood vessels, and few Leydig cells examined in the interstitial tissue [92]. ZnO NP (422 mg/kg/day) exposure for 4 weeks provoked in adult albino rats congestion in blood vessels and detached germinal epithelium from basement membrane, along with absence of spermatozoa in some seminiferous tubules [93]. ZnO NP exposure in albino rats also induced histological abnormalities including disorganization, vacuolation and detachment of germ cells in testicular tissues [74]. Overall, it is ascertained that any damage in the seminiferous tubules may disturb the normal process of spermatogenesis, resulting in the production of abnormal spermatozoa. As supportive references, the table below summarizes literature articles on the exposure of various NPs that induced several histological changes in the seminiferous tubules, provoking consequent reduction in the sperm number by changing the pattern of spermatogenic cells. It is therefore demonstrated that the exposure to different NPs, such as Ni NPs [94], Ag NPs and CeO2 NPs [95], induces histopathological changes in the seminiferous tubules leading to decline in sperm number (Table 1).

Table 2. NPs induce histological abnormalities in sperm and seminiferous tubules, disturbing sperm production.

| Test Material | Histological Evaluation | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticles | Sperm Morphology | Seminiferous Tubules | |

| Nickel nanoparticles | Increased number of abnormal sperms in epididymis, cell apoptosis, no proper arrangement of germinal cells, large gap in lumen of seminiferous tubules | [94] | |

| Silver nanoparticles | Different sperm cell abnormalities including double head, long tail, No hook or wrong hook attachment | Adverse hypertrophic seminiferous tubules | [96] |

| Development of abnormal spermatids | Atrophy in seminiferous tubules, necrosis and degradation of spermatogenic cells, and in spermatogonia and Sertoli cells, ultra-structural alterations | [82] | |

| Shrunken seminiferous tubules, loss of sperms in seminiferous tubules, presence of multinucleated giant cells | [91] | ||

| Sperm with coiled, bent and headless tail, detached head | Increased desquamation in the lumen | [97] | |

| Zinc oxide nanoparticles | Detachment (D), sloughing (S), vacuoles (V) in seminiferous tubules, loss of spermatids, disorganization of germ cells, vacuolization in germinal epithelium | [98] | |

| Titanium dioxide nanoparticles | Amorphous head, double tails of sperm, double head with fused tails, short and knobbed hook | Depletion and necrosis in spermatogenic cells, vacuolation | [99] |

| Zinc oxide nanoparticles and titanium dioxide nanoparticles | Massive head, double hook, double tail with pin head, folded spermatozoa | Seminiferous tubules with variation in size, depletion in spermatogenic cells, necrosis in spermatogenic cells, increased luminal width, congestion in interstitial blood vessels | [28] |

| Cerium oxide nanoparticles | Necrosis in seminiferous tubules, apoptosis in interstitial tissues, loss of spermatozoa, decline in the number of Sertoli cells, Leydig cells, and spermatids | [95] | |

| Silica-gold nanoparticles | Empty seminiferous tubules | [79] | |

| Aluminum oxide nanoparticle | Vacuolization, edema in interstitial cells and congestion in blood vessels, necrosis in spermatogenic cells | [100] | |

| Anatase titanium dioxide nanoparticles | Coil and folded sperm with missing cap | [101] | |

3.3. Adverse Effects of NPs on Sperm Cells

Testicular weight depends on the germ cell mass, and therefore a decrease in testicular weight may be due to the death of germ cells and defects in spermatogenesis [102]. These changes may be due to NPs that, after accumulating in testes, may induce their toxicity by altering sperm morphology, number and viability. The impact of different NPs varies from species to species. The intragastrical administration of TiO2 NPs at doses of 10, 50 and 100 mg/kg BW induced reproductive toxicity in male mice. Results revealed that TiO2 NPs exposure led to increased sperm malformation and decreased germ cell number [103]. The crossing ability of TiO2 NPs through the BTB enables them to reach and accumulate in the testes [78].

3.4. Adverse Effects of NPs on Hormones Involved in Sperm Production

Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis is the hormonal system in which the hypothalamus secretes the gonadotropin-releasing hormone that reaches the pituitary gland via blood, inducing the production of LH and FSH, which is further transported to testes. It is known that LH stimulates the Leydig cells to release T in the seminiferous tubules, which are the site of spermatogenesis and where spermatozoa are produced. Moreover, the seminiferous tubules contain an epithelium with a number of scattered cells known as Sertoli cells, which provide support and nutrients to immature sperm cells. NPs can interfere with the levels of secreted hormones by provoking a negative impact on the pituitary and hypothalamus, resulting in the reduction of FSH and LH secretion and a consequent further decline in the T level. Decrease in FSH exacerbates the testicular damage, while the T level reflects the extent of spermatogenic cell depletion as well as the degree of altered spermatogenesis. It was documented that Ni NPs exposure at different doses (5, 15, 45 mg/kg BW) decreased the value of FSH and T, thus indicating the occurrence of testicular injury [85].

Hormones play important roles in regulating the development of the reproductive system as well as in controlling its activities. In the last two decades, several research works have focused on the endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) regarding reproductive health [99]. Some hormones may be altered after exposure to different NPs. It was reported that intravenous administration of Ag NPs at low dose (1 mg/kg/dose) in male CDI mouse serum significantly increased testosterone level [104]. Testosterone level was also highly increased in male rats when gold nanoparticles (Au NPs) were intraperitoneally administered at concentrations of 25, 50, and 100 ppm. Besides the augmented T level, highly significant increases in LH and FSH levels were also observed in male rats after 10 days of Au NPs exposure, in combination with increased infertility [105]. Conversely, it was observed that exposure to some NPs reduced the T level, as found in mice challenged with TiO2 NPs (300 mg/kg), with further evidence of the beneficial effects induced by quercetin [106]. However, it is worthy of note that during prepubertal development of male Wistar rats the levels of FSH, LH and T did not change after daily exposure to Ag NPs at doses of 15 and 30 µg/kg [107]. It was also observed that exposure to Ag NPs at doses of 0, 10 and 50 mg/kg BW for the duration of 7 and 28 days in male rats induced dose and time dependent changes in LH, FSH and T level [95]. Similarly, oral administration of Al2O3 NPs and ZnO NPs at doses of 70 and 100 mg/kg BW/day for 75 days in Wistar male albino rats induced, respectively, reduction in TSH and T levels, and increases in LH and FSH levels [90]. Therefore, it may be stated that changes in hormone levels might be influenced by various factors including size, type and exposure time of NPs. Overall, decrease in T level leads towards testicular injury, while the rise in LH and FSH level might be related to the onset of negative feedback mechanisms [99].

References

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 908–931.

- Tiwari, J.N.; Tiwari, R.N.; Kim, K.S. Zero-dimensional, one-dimensional, two-dimensional and three-dimensional nanostructured materials for advanced electrochemical energy devices. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2012, 57, 724–803.

- Vance, M.E.; Kuiken, T.; Vejerano, E.P.; McGinnis, S.P.; Hochella Jr, M.F.; Rejeski, D.; Hull, M.S. Nanotechnology in the real world: Redeveloping the nanomaterial consumer products inventory. Beilstein J. Nanotech. 2015, 6, 1769–1780.

- Ema, M.; Kobayashi, N.; Naya, M.; Hanai, S.; Nakanishi, J. Reproductive and developmental toxicity studies of manufactured nanomaterials. Reprod. Toxicol. 2010, 30, 343–352.

- Oberdorster, G.; Oberdorster, E.; Oberdorster, J. Nanotoxicology: An emerging discipline evolution from studies of ultrafine particles. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 823–839.

- Maisano, M.; Cappello, T.; Catanese, E.; Vitale, V.; Natalotto, A.; Giannetto, A.; Barreca, D.; Brunelli, E.; Mauceri, A.; Fasulo, S. Developmental abnormalities and neurotoxicological effects of CuO NPs on the black sea urchin Arbacia lixula by embryotoxicity assay. Mar. Environ. Res. 2015, 111, 121–127.

- Cappello, T.; Vitale, V.; Oliva, S.; Villari, V.; Mauceri, A.; Fasulo, S.; Maisano, M. Alteration of neurotransmission and skeletogenesis in sea urchin Arbacia lixula embryos exposed to copper oxide nanoparticles. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C 2017, 199, 20–27.

- Tsuji, J.S.; Maynard, A.D.; Howard, P.C.; James, J.T.; Lam, C.W.; Warheit, D.B.; Santamaria, A.B. Research strategies for safety evaluation of nanomaterials, part IV: Risk assessment of nanoparticles. Toxicol. Sci. 2006, 89, 42–50.

- Jamuna Bai, A.; Ravishankar Rai, V. Environmental risk, human health, and toxic effects of nanoparticles. Nanomater. Environ. Protect. 2014, 523.

- Yah, C.S. The toxicity of Gold Nanoparticles in relation to their physiochemical properties. Biomed. Res. 2013, 24, 400–413.

- Wu, T.; Tang, M. Review of the effects of manufactured nanoparticles on mammalian target organs. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2018, 38, 25–40.

- Sajid, M.; Ilyas, M.; Basheer, C.; Tariq, M.; Daud, M.; Baig, N.; Shehzad, F. Impact of nanoparticles on human and environment: Review of toxicity factors, exposures, control strategies, and future prospects. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 4122–4143.

- Joris, F.; Manshian, B.B.; Peynshaert, K.; De Smedt, S.C.; Braeckmans, K.; Soenen, S.J. Assessing nanoparticle toxicity in cell-based assays: Influence of cell culture parameters and optimized models for bridging the in vitro–in vivo gap. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 8339–8359.

- Verma, A.; Stellacci, F. Effect of surface properties on nanoparticle–cell interactions. Small 2010, 6, 12–21.

- Yildirimer, L.; Thanh, N.T.; Loizidou, M.; Seifalian, A.M. Toxicology and clinical potential of nanoparticles. Nano Today 2011, 6, 585–607.

- Mu, Q.; Jiang, G.; Chen, L.; Zhou, H.; Fourches, D.; Tropsha, A.; Yan, B. Chemical basis of interactions between engineered nanoparticles and biological systems. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 7740–7781.

- Behzadi, S.; Serpooshan, V.; Tao, W.; Hamaly, M.A.; Alkawareek, M.Y.; Dreaden, E.C.; Brown, D.; Alkilany, A.M.; Farokhzad, O.C.; Mahmoudi, M. Cellular uptake of nanoparticles: Journey inside the cell. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4218–4244.

- Wisniewski, P.; Romano, R.M.; Kizys, M.M.L.; Oliveira, K.; Kasamatsu, T.; Giannocco, G.; Chiamolera, M.I.; Dias-da-Silva, M.; Romano, M.A. Adult exposure to bisphenol A (BPA) in Wistar rats reduces sperm quality with disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis. Toxicology 2015, 329, 1–9.

- Hougaard, K.S.; Campagnolo, L.; Chavatte-Palmer, P.; Tarrade, A.; Rousseau-Ralliard, D.; Valentino, S.; Park, M.V.D.Z.; de Jong, W.H.; Wolterink, G.; Piersma, A.H.; et al. A perspective on the developmental toxicity of inhaled nanoparticles. Reprod. Toxicol. 2015, 56, 118–140.

- Das, J.; Choi, Y.J.; Song, H.; Kim, J.H. Potential toxicity of engineered nanoparticles in mammalian germ cells and developing embryos: Treatment strategies and anticipated applications of nanoparticles in gene delivery. Hum. Reprod. Update 2016, 22, 588–619.

- Azenabor, A.; Ekun, A.O.; Akinloye, O. Impact of inflammation on male reproductive tract. J. Reprod. Infertil. 2015, 16, 123.

- Walczak–Jedrzejowska, R.; Wolski, J.K.; Slowikowska–Hilczer, J. The role of oxidative stress and antioxidants in male fertility. Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 2013, 66, 60.

- Ren, C.; Hu, X.; Zhou, Q. Graphene oxide quantum dots reduce oxidative stress and inhibit neurotoxicity in vitro and in vivo through catalase-like activity and metabolic regulation. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1700595.

- Bisht, S.; Faiq, M.; Tolahunase, M.; Dada, R. Oxidative stress and male infertility. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2017, 14, 470–485.

- Han, J.W.; Jeong, J.K.; Gurunathan, S.; Choi, Y.J.; Das, J.; Kwon, D.N.; Cho, S.G.; Park, C.; Seo, H.G.; Park, J.K.; et al. Male-and female-derived somatic and germ cell-specific toxicity of silver nanoparticles in mouse. Nanotoxicology 2016, 10, 361–373.

- Ema, M.; Hougaard, K.S.; Kishimoto, A.; Honda, K. Reproductive and developmental toxicity of carbon-based nanomaterials: A literature review. Nanotoxicology 2016, 10, 391–412.

- Opris, R.; Toma, V.; Olteanu, D.; Baldea, I.; Baciu, A.M.; Lucaci, F.I.; Berghian-Sevastre, A.; Tatomir, C.; Moldovan, B.; Clichici, S.; et al. Effects of silver nanoparticles functionalized with Cornus mas L. extract on architecture and apoptosis in rat testicle. Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 275–299.

- Ogunsuyi, O.M.; Ogunsuyi, O.I.; Akanni, O.; Alabi, O.A.; Alimba, C.G.; Adaramoye, O.A.; Cambier, S.; Eswara, S.; Gutleb, A.C.; Bakare, A.A. Alteration of sperm parameters and reproductive hormones in Swiss mice via oxidative stress after co-exposure to titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Andrologia 2020, 52, e13758.

- Al-Bairuty, G.A.; Taha, M.N. Effects of copper nanoparticles on reproductive organs of male albino rats. Int. J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 143, 201617.

- Kong, L.; Hu, W.; Lu, C.; Cheng, K.; Tang, M. Mechanisms underlying nickel nanoparticle induced reproductive toxicity and chemo-protective effects of vitamin C in male rats. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 259–265.

- Deonandan, R.; Jaleel, M. Global decline in semen quality: Ignoring the developing world introduces selection bias. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2012, 5, 303.

- Huang, C.; Li, B.; Xu, K.; Liu, D.; Hu, J.; Yang, Y.; Nie, H.; Fan, L.; Zhu, W. Decline in semen quality among 30,636 young Chinese men from 2001 to 2015. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 107, 83–88.

- Auger, J.; Kunstmann, J.M.; Czyglik, F.; Jouannet, P. Decline in semen quality among fertile men in Paris during the past 20 years. New Eng. J. Med. 1995, 332, 281–285.

- Lan, Z.; Yang, W.X. Nanoparticles and spermatogenesis: How do nanoparticles affect spermatogenesis and penetrate the blood–testis barrier. Nanomedicine 2012, 7, 579–596.

- Shi, L.G.; Yang, R.J.; Yue, W.B.; Xun, W.J.; Zhang, C.X.; Ren, Y.S.; Shi, L.; Lei, F.L. Effect of elemental nano-selenium on semen quality, glutathione peroxidase activity, and testis ultrastructure in male Boer goats. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2010, 118, 248–254.

- Park, E.J.; Bae, E.; Yi, J.; Kim, Y.; Choi, K.; Lee, S.H.; Yoon, J.; Lee, B.C.; Park, K. Repeated-dose toxicity and inflammatory responses in mice by oral administration of silver nanoparticles. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 30, 162–168.

- Shittu, O.K.; Aaron, S.Y.; Oladuntoye, M.D.; Lawal, B. Diminazene aceturate modified nanocomposite for improved efficacy in acute trypanosome infection. J. Acute Dis. 2018, 7, 36.

- Lipskind, S.T.; Gargiulo, A.R. Computer-assisted laparoscopy in fertility preservation and reproductive surgery. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2013, 20, 435–445.

- Barkalina, N.; Charalambous, C.; Jones, C.; Coward, K. Nanotechnology in reproductive medicine: Emerging applications of nanomaterials. Nanomed. Nanotech. Biol. Med. 2014, 10, e921–e938.

- Wang, A.Z.; Bagalkot, V.; Vasilliou, C.C.; Gu, F.; Alexis, F.; Zhang, L.; Shaikh, M.; Yuet, K.; Langer, R.; Kantoff, P.W.; et al. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle–aptamer bioconjugates for combined prostate cancer imaging and therapy. Chem. Med. Chem. 2008, 3, 1311–1315.

- Thoeny, H.C.; Triantafyllou, M.; Birkhaeuser, F.D.; Froehlich, J.M.; Tshering, D.W.; Binser, T.; Fleischmann, A.; Vermathen, P.; Studer, U.E. Combined ultrasmall superparamagnetic particles of iron oxide–enhanced and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging reliably detect pelvic lymph node metastases in normal-sized nodes of bladder and prostate cancer patients. European Urol. 2009, 55, 761–769.

- Kim, D.; Jeong, Y.Y.; Jon, S. A drug-loaded aptamer−gold nanoparticle bioconjugate for combined CT imaging and therapy of prostate cancer. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3689–3696.

- Campos, V.F.; de Leon, P.M.M.; Komninou, E.R.; Dellagostin, O.A.; Deschamps, J.C.; Seixas, F.K.; Collares, T. NanoSMGT: Transgene transmission into bovine embryos using halloysite clay nanotubes or nanopolymer to improve transfection efficiency. Theriogenology 2011, 76, 1552–1560.

- Yang, P.T.; Hoang, L.; Jia, W.W.; Skarsgard, E.D. In utero gene delivery using chitosan-DNA nanoparticles in mice. J. Surg. Res. 2011, 171, 691–699.

- Kunzmann, A.; Andersson, B.; Thurnherr, T.; Krug, H.; Scheynius, A.; Fadeel, B. Toxicology of engineered nanomaterials: Focus on biocompatibility, biodistribution and biodegradation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gen. Subj. 2011, 1810, 361–373.

- Taylor, U.A.W.E.; Barchanski, A.; Garrels, W.; Klein, S.; Kues, W.; Barcikowski, S.; Rath, D. Toxicity of gold nanoparticles on somatic and reproductive cells. In Nano-Biotechnology for Biomedical and Diagnostic Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 125–133.

- Taylor, U.; Petersen, S.; Barchanski, A.; Mittag, A.; Barcikowski, S.; Rath, D. Influence of gold nanoparticles on vitality parameters of bovine spermatozoa. In Reproduction in Domestic Animals; Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 45, p. 60.

- Wiwanitkit, V.; Sereemaspun, A.; Rojanathanes, R. Effect of gold nanoparticles on spermatozoa: The first world report. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 91, e7–e8.

- Skuridin, S.G.; Dubinskaya, V.A.; Rudoy, V.M.; Dement’eva, O.V.; Zakhidov, S.T.; Marshak, T.L.; Evdokimov, Y.M. Effect of gold nanoparticles on DNA package in model systems. In Doklady Biochemistry and Biophysics; Springer Nature AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2010; Volume 432, p. 141.

- Niska, K.; Zielinska, E.; Radomski, M.W.; Inkielewicz-Stepniak, I. Metal nanoparticles in dermatology and cosmetology: Interactions with human skin cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 295, 38–51.

- Olugbodi, J.O.; David, O.; Oketa, E.N.; Lawal, B.; Okoli, B.J.; Mtunzi, F. Silver nanoparticles stimulates spermatogenesis impairments and hematological alterations in testis and epididymis of male rats. Molecules 2020, 25, 1063.

- Donnelly, R.F.; Singh, T.R.R.; Morrow, D.I.; Woolfson, A.D. Microneedle-Mediated Transdermal and Intradermal Drug Delivery; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 1–216.

- Filon, F.L.; Mauro, M.; Adami, G.; Bovenzi, M.; Crosera, M. Nanoparticles skin absorption: New aspects for a safety profile evaluation. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015, 72, 310–322.

- Rancan, F.; Gao, Q.; Graf, C.; Troppens, S.; Hadam, S.; Hackbarth, S.; Kembuan, C.; Blume-Peytavi, U.; Ruhl, E.; Lademann, J.; et al. Skin penetration and cellular uptake of amorphous silica nanoparticles with variable size, surface functionalization, and colloidal stability. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 6829–6842.

- Hansson, G.C. Role of mucus layers in gut infection and inflammation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2012, 15, 57–62.

- Bergin, I.L.; Witzmann, F.A. Nanoparticle toxicity by the gastrointestinal route: Evidence and knowledge gaps. Int. J. Biomed. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2013, 3, 163–210.

- Hong, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ge, Y.; Chen, M.; Hong, J.; Wang, L. Exposure to TiO2 nanoparticles induces immunological dysfunction in mouse testitis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 346–355.

- Miresmaeili, S.M.; Halvaei, I.; Fesahat, F.; Fallah, A.; Nikonahad, N.; Taherinejad, M. Evaluating the role of silver nanoparticles on acrosomal reaction and spermatogenic cells in rat. Iran. J. Reprod. Med. 2013, 11, 423.

- Sleiman, H.K.; Romano, R.M.; Oliveira, C.A.D.; Romano, M.A. Effects of prepubertal exposure to silver nanoparticles on reproductive parameters in adult male Wistar rats. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2013, 76, 1023–1032.

- Dekkers, S.; Krystek, P.; Peters, R.J.; Lankveld, D.P.; Bokkers, B.G.; van Hoeven-Arentzen, P.H.; Bouwmeester, H.; Oomen, A.G. Presence and risks of nanosilica in food products. Nanotoxicology 2011, 5, 393–405.

- Winkler, H.C.; Suter, M.; Naegeli, H. Critical review of the safety assessment of nano-structured silica additives in food. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2016, 14, 44.

- Rincker, M.J.; Hill, G.M.; Link, J.E.; Meyer, A.M.; Rowntree, J.E. Effects of dietary zinc and iron supplementation on mineral excretion, body composition, and mineral status of nursery pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 83, 2762–2774.

- Rim, K.T.; Song, S.W.; Kim, H.Y. Oxidative DNA damage from nanoparticle exposure and its application to workers’ health: A literature review. Saf. Health Work 2013, 4, 177–186.

- Jackson, P.; Halappanavar, S.; Hougaard, K.S.; Williams, A.; Madsen, A.M.; Lamson, J.S.; Andersen, O.; Yauk, C.; Wallin, K.; Vogel, U. Maternal inhalation of surface-coated nanosized titanium dioxide (UV-Titan) in C57BL/6 mice: Effects in prenatally exposed offspring on hepatic DNA damage and gene expression. Nanotoxicology 2013, 7, 85–96.

- Bakand, S.; Hayes, A. Toxicological considerations, toxicity assessment, and risk management of inhaled nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 929.

- Meier, M.J.; O’Brien, J.M.; Beal, M.A.; Allan, B.; Yauk, C.L.; Marchetti, F. In utero exposure to benzo [a] pyrene increases mutation burden in the soma and sperm of adult mice. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 82–88.

- Li, C.; Taneda, S.; Taya, K.; Watanabe, G.; Li, X.; Fujitani, Y.; Ito, Y.; Nakajima, T.; Suzuki, A.K. Effects of inhaled nanoparticle-rich diesel exhaust on regulation of testicular function in adult male rats. Inhal. Toxicol. 2009, 21, 803–811.

- Boisen, A.M.Z.; Shipley, T.; Jackson, P.; Wallin, H.; Nellemann, C.; Vogel, U.; Yauk, C.L.; Hougaard, K.S. In utero exposure to nanosized carbon black (Printex90) does not induce tandem repeat mutations in female murine germ cells. Reprod. Toxicol. 2013, 41, 45–48.

- Skovmand, A.; Jensen, A.C.; Maurice, C.; Marchetti, F.; Lauvås, A.J.; Koponen, I.K.; Jensen, K.A.; Goericke-Pesch, S.; Vogel, U.B.; Hougaard, K.S. Effects of maternal inhalation of carbon black nanoparticles on reproductive and fertility parameters in a four-generation study of male mice. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2019, 16, 13.

- Mostafalou, S.; Mohammadi, H.; Ramazani, A.; Abdollahi, M. Different biokinetics of nanomedicines linking to their toxicity; an overview. Daru J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 21, 14.

- Wang, R.; Song, B.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, A.; Shao, L. Potential adverse effects of nanoparticles on the reproductive system. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 8487–8506.

- Li, C.; Li, X.; Suzuki, A.K.; Zhang, Y.; Fujitani, Y.; Nagaoka, K.; Watanabe, G.; Taya, K. Effects of exposure to nanoparticle-rich diesel exhaust on pregnancy in rats. J. Reprod. Dev. 2013, 59, 14–150.

- Rollerova, E.; Jurcovicova, J.; Mlynarcikova, A.; Sadlonova, I.; Bilanicova, D.; Wsolova, L.; Kiss, A.; Kovriznych, J.; Kronek, J.; Ciampor, F.; et al. Delayed adverse effects of neonatal exposure to polymeric nanoparticle poly (ethylene glycol)-block-polylactide methyl ether on hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis development and function in Wistar rats. Reprod. Toxicol. 2015, 57, 165–175.

- Hussein, M.M.; Ali, H.A.; Saadeldin, I.M.; Ahmed, M.M. Querectin alleviates zinc oxide nanoreprotoxicity in male albino rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2016, 30, 489–496.

- Zhao, H.; Gu, W.; Ye, L.; Yang, H. Biodistribution of PAMAM dendrimer conjugated magnetic nanoparticles in mice. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2014, 25, 769–776.

- Sundarraj, K.; Manickam, V.; Raghunath, A.; Periyasamy, M.; Viswanathan, M.P.; Perumal, E. Repeated exposure to iron oxide nanoparticles causes testicular toxicity in mice. Environ. Toxicol. 2017, 32, 594–608.

- Kielbik, P.; Kaszewski, J.; Dabrowski, S.; Faundez, R.; Witkowski, B.S.; Wachnicki, L.; Zhydachevskyy, Y.; Sapierzynski, R.; Gajewski, Z.; Godlewski, M.M. Transfer of orally administered ZnO: Eu nanoparticles through the blood–testis barrier: The effect on kinetic sperm parameters and apoptosis in mice testes. Nanotechnology 2019, 30, 455101.

- Gao, G.; Ze, Y.; Zhao, X.; Sang, X.; Zheng, L.; Ze, X.; Gui, S.; Sheng, L.; Sun, Q.; Hong, J.; et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticle-induced testicular damage, spermatogenesis suppression, and gene expression alterations in male mice. J. Haz. Mater. 2013, 258, 133–143.

- Leclerc, L.; Klein, J.P.; Forest, V.; Boudard, D.; Martini, M.; Pourchez, J.; Blanchin, M.G.; Cottier, M. Testicular biodistribution of silica-gold nanoparticles after intramuscular injection in mice. Biomed. Microdev. 2015, 17, 66.

- Miura, N.; Ohtani, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Yoshioka, H.; Hwang, G.W. High sensitivity of testicular function to titanium nanoparticles. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 42, 359–366.

- Wang, Z.; Qu, G.; Su, L.; Wang, L.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Liu, S.; Jiang, G. Evaluation of the biological fate and the transport through biological barriers of nanosilver in mice. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 6691–6697.

- Thakur, M.; Gupta, H.; Singh, D.; Mohanty, I.R.; Maheswari, U.; Vanage, G.; Joshi, D.S. Histopathological and ultra structural effects of nanoparticles on rat testis following 90 days (chronic study) of repeated oral administration. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2014, 12, 42.

- Zhou, Q.; Yue, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhou, R.; Liu, L. Exposure to PbSe nanoparticles and male reproductive damage in a rat model. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 13408–13416.

- Adeyemi, O.S.; Orekoya, B. Lipid profile and oxidative stress markers in rats following oral and repeated exposure to Fijk herbal mixture. J. Toxicol. 2014, 2014, 876035.

- Kong, L.; Tang, M.; Zhang, T.; Wang, D.; Hu, K.; Lu, W.; Wei, C.; Liang, G.; Pu, Y. Nickel nanoparticles exposure and reproductive toxicity in healthy adult rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 21253–21269.

- Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J.; Dziendzikowska, K.; Lankoff, A.; Dobrzyńska, M.; Instanes, C.; Brunborg, G.; Gajowik, A.; Radzikowska, J.; Wojewodzka, M.; Kruszewski, M. Silver nanoparticles effects on epididymal sperm in rats. Toxicol. Lett. 2012, 214, 251–258.

- Tang, Y.; Chen, B.; Hong, W.; Chen, L.; Yao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Aguilar, Z.P.; Xu, H. ZnO nanoparticles induced male reproductive toxicity based on the effects on the endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling pathway. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 9563.

- Mahfouz, R.; Sharma, R.; Thiyagarajan, A.; Kale, V.; Gupta, S.; Sabanegh, E.; Agarwal, A. Semen characteristics and sperm DNA fragmentation in infertile men with low and high levels of seminal reactive oxygen species. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 94, 2141–2146.

- Soliman, A.H.M.; Ibrahim, I.A.; Shehata, M.A.; Mohammed, H.O. Histopathological and genetic study on the protective role of β-carotene on testicular tissue of adult male albino rats treated with titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2020, 14, 9–19.

- Yousef, M.I. Reproductive toxicity of aluminum oxide nanoparticles and zinc oxide nanoparticles in male rats. Nanoparticle 2019, 1, 3.

- Ahmed, S.M.; Abdelrahman, S.A.; Shalaby, S.M. Evaluating the effect of silver nanoparticles on testes of adult albino rats (histological, immunohistochemical and biochemical study). J. Mol. Histol. 2017, 48, 9–27.

- El-Azab, N.E.E.; Elmahalaway, A.M. A Histological and Immunohistochemical Study on Testicular Changes Induced by Sliver Nanoparticles in Adult Rats and the Possible Protective Role of Camel Milk. Egypt. J. Histol. 2020, 42, 1044–1058.

- Mesallam, D.I.; Deraz, R.H.; Aal, S.M.A.; Ahmed, S.M. Toxicity of Subacute Oral Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Testes and Prostate of Adult Albino Rats and Role of Recovery. J. Histol. Histopathol. 2019, 6, 1–11.

- Hu, W.; Yu, Z.; Gao, X.; Wu, Y.; Tang, M.; Kong, L. Study on the damage of sperm induced by nickel nanoparticle exposure. Environ. Geochem. Health 2020, 42, 1715–1724.

- Qin, F.; Shen, T.; Li, J.; Qian, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, G.; Tong, J. SF-1 mediates reproductive toxicity induced by Cerium oxide nanoparticles in male mice. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 17, 41.

- Iyiola, O.; Olafimihan, T.F.; Sulaiman, F.A.; Anifowoshe, A.T. Genotoxicity and histopathological assessment of silver nanoparticles in Swiss albino mice. Cuad. Investig. UNED 2018, 10, 102–109.

- Lafuente, D.; Garcia, T.; Blanco, J.; Sánchez, D.J.; Sirvent, J.J.; Domingo, J.L.; Gómez, M. Effects of oral exposure to silver nanoparticles on the sperm of rats. Reprod. Toxicol. 2016, 60, 133–139.

- Rafiee, Z.; Khorsandi, L.; Nejad-Dehbashi, F. Protective effect of zingerone against mouse testicular damage induced by zinc oxide nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 25814–25824.

- Bakare, A.A.; Udoakang, A.J.; Anifowoshe, A.T.; Fadoju, O.M.; Ogunsuyi, O.I.; Alabi, O.A.; Alimba, C.G.; Oyeyemi, I.T. Genotoxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using the mouse bone marrow micronucleus and sperm morphology assays. J. Pollut. Eff. Cont. 2016, 4, 41.

- Hamdi, H. Testicular dysfunction induced by aluminum oxide nanoparticle administration in albino rats and the possible protective role of the pumpkin seed oil. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2020, 81, 42.

- Smith, M.A.; Michael, R.; Aravindan, R.G.; Dash, S.; Shah, S.I.; Galileo, D.S.; Martin-DeLeon, P.A. Anatase titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mice: Evidence for induced structural and functional sperm defects after short-, but not long-, term exposure. As. J. Androl. 2015, 17, 261.

- Karimi, S.; Khorsandi, L.; Nejaddehbashi, F. Protective effects of curcumin on testicular toxicity induced by titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mice. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2019, 23, 344.

- Song, G.; Lin, L.; Liu, L.; Wang, K.; Ding, Y.; Niu, Q.; Mu, L.; Wang, H.; Shen, H.; Guo, S. Toxic effects of anatase titanium dioxide nanoparticles on spermatogenesis and testicles in male mice. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2017, 26, 2739–2745.

- Zhang, X.F.; Gurunathan, S.; Kim, J.H. Effects of silver nanoparticles on neonatal testis development in mice. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 6243.

- Behnammorshedi, M.; Nazem, H.; Moghadam, M.S. The effect of gold nanoparticle on luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, testosterone and testis in male rat. Biomed. Res. 2015, 26, 348–352.

- Khorsandi, L.; Orazizadeh, M.; Moradi-Gharibvand, N.; Hemadi, M.; Mansouri, E. Beneficial effects of quercetin on titanium dioxide nanoparticles induced spermatogenesis defects in mice. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 5595–5606.

- Mathias, F.T.; Romano, R.M.; Kizys, M.M.; Kasamatsu, T.; Giannocco, G.; Chiamolera, M.I.; Dias-da-Silva, M.R.; Romano, M.A. Daily exposure to silver nanoparticles during prepubertal development decreases adult sperm and reproductive parameters. Nanotoxicology 2015, 9, 64–70.