| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Matthew Watson | + 3141 word(s) | 3141 | 2021-03-09 03:59:21 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 3141 | 2021-03-10 07:31:00 | | |

Video Upload Options

The gut microbiota refers to the collective of bacteria, archaea, viruses, and eukaryotic microbes that reside in the gastrointestinal tract.

1. Protein Digestion & Amino Acid Absorption

Following a protein-rich meal, effective digestion and absorption of dietary proteins is an essential first step in facilitating a muscle protein synthetic response [1]. Protein digestion begins in the acidic environment of the stomach, where low pH-induced protein denaturation yields more accessible polypeptides for subsequent protein processing by activated pepsin. Once in the small intestine, proteases and peptidases produced and secreted by the pancreas (e.g., trypsin, chymotrypsin, carboxypeptidase) and the intestinal epithelium (e.g., aminopeptidase N) further advance the digestive process. While the majority of dietary protein is absorbed in the small intestine, a small but physiologically relevant quantity (~6–18 g/day) of peptides and amino acids [2] will enter the large intestine for microbial fermentation [3].

Given the importance of maximizing circulating amino acid availability to optimize post-prandial MPS [4][5], any defects in the process of protein digestion and absorption may detract from anabolic potential. For example, it has been demonstrated that postprandial amino acid kinetics are affected by age [6]. Moreover, peak plasma appearance of amino acids following a high protein meal is substantially delayed in healthy older vs. younger individuals [6]. Taken together, these findings allude to the possibility that slowed protein digestion and absorption rates in older adults may diminish muscle protein synthetic responses to protein feeding. Identification of the biological mechanisms underlying age-related differences in protein digestion and absorption that appear to coalesce to impair MPS [7] may aid in the development of strategies to maximize anabolic response to protein feeding with aging.

The prominent role of gut microbiota in energy harvest has long been known [8]. In regards to the metabolism of dietary protein, gut microbes are involved in digestive, absorptive, and metabolic processing of amino acids within the gastrointestinal tract [9]. Pioneering work in animal models first highlighted an influence of intestinal microbiota on proteolytic enzyme activity in the small intestine. Conventionalization of germfree (GF) piglets with feces derived from a clinically healthy sow was demonstrated to reduce the activity of aminopeptidase N [10], a brush border enzyme involved in protein hydrolysis. Moreover, monoassociation of GF pigs with commensal Escherichia coli strains is demonstrated to induce maturational changes of the intestinal brush border characterized by increases in enzymatic activity (i.e., sucrase, glucoamylase, and aminopeptidase N) [11]. These findings emphasize the significance of gut microbiota in shaping metabolic enzymatic activity in the small intestine (Table 1). Interestingly and somewhat paradoxically, activity of aminopeptidase and other protein digestive enzymes appear to be elevated in senescent rats [12], which may serve to offset age-related declines in gastric pepsin secretion [13]. Whether the microbiome plays a role in this apparent compensatory response, and if a similar phenomenon is observed in aging humans remains to be determined.

A more direct role for gut microbes in protein digestion is observed through the proteolytic fermentation of undigested peptides in the large intestine. Due to the variety of toxic substances this may produce (e.g., hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, p-cresyl and indoxyl sulfate), this process is generally considered to be harmful to the host [14]. Indoxyl sulfate is shown to potentiate skeletal muscle atrophy via induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), inflammatory cytokines, and myoatrophic gene expression [15]. The greater abundance of indoxyl sulfate and other toxic byproducts (p-cresyl) observed in older individuals [16] may be attributed to an increase in protein fermenting bacteria such as Clostridium perfringens, Desulfovibrio, Peptostreptococcus, Acadaminococcus, Veillonella, Propionibacterium, Bacillus, Bacteroides, and/or Staphylococcus [17]. More work is needed to pinpoint the precise microbial dynamics contributing to this age-related increase in toxic microbial metabolites as a means of providing therapeutic targets for future interventional studies.

Contrariwise, SCFA’s and biogenic amines, which are also end products of protein fermentation in the large intestine, serve many important physiologic functions and are thought to provide ~10% of daily energy requirements [18]. Colon-derived SCFA’s also appear to play a role in protein metabolism and anabolic responsiveness [19]. For instance, chronic supplementation with the SCFA butyrate has been reported to prevent hindlimb muscle loss in aging mice [20], and a butyrate-containing SCFA cocktail was recently observed to increase muscle mass in mice lacking a microbiome [21]. Of the mechanisms through which butyrate is purported to influence protein metabolism, the anti-inflammatory benefits of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition is among the most pervasively discussed [20]. Microbial-derived SCFA’s are also demonstrated to promote epithelial barrier function, thereby reducing intestinal permeability and protecting against inflammation [22]. In this context, declines in butyrogenic microflora (e.g., Roseburia, Clostridia, and Eubacteria) [23] that are characteristic of aging [24] may be viewed as a key contributor to age-related anabolic resistance. Intriguingly, several reports examining the microbiome of healthy, long-lived animal and human models (≥90 years) have observed microbial signatures containing elevated levels of SCFA producers [25][26][27]. Interpreted in unison, these findings highlight that age-related changes to protein digestion and absorption in the small intestine, via microbial interactions with proteolytic enzymes, may contribute to anabolic responsiveness. Nevertheless, the microbiome may have its greatest impact on protein metabolism within the large intestine through the production of various protein metabolites with implications for down-stream protein synthetic processes, which will be discussed in greater detail in future sections.

2. Circulating Amino Acid Availability

Postprandial circulating amino acid kinetics profoundly influence whole body protein anabolism [28]. To overcome age-related deficits in protein digestion and absorption and to maintain circulating amino acid availability, older individuals are advised to ingest a daily protein quantity that is in excess of the Recommended Dietary Allowance [29]. While this elevated protein intake may help to attenuate declines in circulating amino acid availability, it is also important to consider the contribution of microbial-derived amino acids to the circulating amino acid pool [30][31]. Relevantly, microorganisms such as Bifidobacteria and Clostridia, which decline during late adulthood [32], yet are observed to increase in healthy 90+ year old individuals [26][27][33][34][35][36], are demonstrated to produce physiologically relevant amino acids from nonspecific nitrogen sources [37][38]. Preliminary evidence for the de novo biosynthesis of amino acids (i.e., lysine) by the gut microflora in vivo was initially provided by comparative experiments using the 15N labeling paradigm in GF and conventionalized rats [39]. This finding has since been confirmed in human studies suggesting that as much as 20% of circulating plasma lysine is derived from intestinal microbial sources [40]. Relevantly, lysine is an essential ketogenic amino acid that plays a fundamental role in muscle protein turnover [41], and high lysine levels have even been linked to human longevity [42]. Interestingly, human aging is associated with a reduction in bacteria such as Prevotella [43] that are involved in lysine biosynthesis [44], and this decline is predictive of physical frailty [45] as well as loss of independence [46]. Perhaps more important than the microbial contribution to the total body supply of lysine, intestinal microbes are estimated to synthesize between 19 to 22% of leucine [30], an essential amino acid that is speculated to play a unique role in the initiation of anabolic intracellular signaling pathways [47]. Longitudinal studies are needed to confirm cross-sectional observations implicating bacteria such as Prevotella, Allistiples, and Barnesiella in the biosynthesis of leucine and other anabolic amino acids [48].

Detracting from circulating amino acid availability, splanchnic extraction of dietary amino acids increases with age [49][50][51], and this phenomenon appears to be exacerbated by obesity [51]. Greater first-pass splanchnic amino acid uptake in older individuals may be explained by increased leucine oxidation in the gut and/or liver [52], as is observed in healthy older men who fail to suppress leucine oxidation in response to experimental hyperglycemia and/or following exercise training [53]. This reduced metabolic flexibility, characterized by a greater reliance on amino acid metabolism, may be influenced by microflora. For example, antimicrobial treatment is demonstrated to suppress leucine oxidation (~15–20%), conceivably through the elimination of subclinical infections [30][54] brought about by maladaptive changes in the gut microbiome [55]. With this in mind, it is intriguing to speculate as to the contribution of age-related microbial dysbiosis to heightened rates of leucine oxidation and thus greater splanchnic sequestration of amino acids (Table 1). To assuage age-related inefficiencies in amino acid availability and utilization, therapies to promote myogenic microbial-derived amino acids and to combat maladaptive microbial alterations that are associated with aberrant changes in protein metabolism are of interest.

3. Anabolic Hormone Responses

The endocrine system plays a fundamental role in the regulation of muscle mass. Insulin, growth hormone (GH), and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), are responsive to exogenous amino acid intake and are shown to influence muscle growth and development throughout life [56]. However, the relevance of transient, systemic elevations of these hormones following protein feeding and/or mechanical stimulation for the promotion of muscle growth is challenged by studies demonstrating muscle hypertrophy [57], intramuscular signaling [58], and MPS [59] independent of endocrine responses. These findings have led to the consensus that endocrine responses following anabolic stimuli appear to play a permissive, rather than stimulatory, role in mediating MPS [56][60]. Nonetheless, associations have been made between age-related changes in body composition with insulin resistance [61][62], and declining GH and IGF-1 levels [63][64][65][66][67]. Collectively, these observations allude to the relevance of anabolic hormonal deficiencies in mediating aging muscle loss, and provide incentive for research examining the etiology of these changes in endocrine regulation.

Conventionally, it is understood that insulin acts upon skeletal muscle to facilitate glucose uptake [68], and plays a permissive role in MPS by upregulating downstream anabolic signaling events [69]. Less commonly discussed is insulin’s anabolic actions through an upregulation of skeletal muscle blood flow, an important determinant of MPS deserving of greater examination due to its prospective relationship with the aging gut microbiome. Though it is currently unclear whether insulin-mediated MPS is independent from [70][71][72], or coincides with [73][74][75], skeletal muscle glucose tolerance, past studies have highlighted how insulin may mediate vasodilation through its influence on endothelial function [62][76][77]. Therefore, it is intriguing to speculate how age-related impairments in insulin-mediated tissue perfusion may detract from anabolic responsiveness.

Recent work by Fujita et al. [78] demonstrated that experimental hyperinsulinemia promotes MPS in a manner that is best predicted by insulin-related changes in skeletal muscle blood flow. Corroborating this observation, Nygren and Nair [79] demonstrated that concurrent insulin and amino acid infusion augments MPS in healthy young adults. The mechanism underlying this insulin-mediated blood flow augmentation was outlined in landmark studies by Steinberg et al. [80] and Scherrer et al. [72], where insulin-mediated activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) was observed. However, experimental hyperinsulinemia has been demonstrated to increase vastus lateralis blood flow in younger but not older (≥65 years), healthy individuals [71].

Aging research suggests that reductions in nitric oxide (NO) biosynthesis and bioavailability, rather than decreased endothelial NO sensitivity, may instigate the attenuated insulin-mediated skeletal muscle perfusion that is hallmark in aging muscle [70][81][82][77]. There is growing support that gut microbes may impair vascular function and contribute to this phenomenon [70][83][81][84]. Specifically, increases in inflammation, oxidative stress and ROS owing to maladaptive changes in the gut microbiome all may limit eNOS release in the presence of insulin [70][83][81][82][85][84]. Meanwhile, antibiotic treatment in aging mice has been demonstrated to suppress gut dysbiosis through the attenuation of pathogenic microbes (e.g., Proteobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, and Desulfovibrio) and reduce inflammation, facilitating improvements in vascular function [70][83]. Though a comprehensive understanding of the ways in which the microbiome seems to impair endothelial insulin sensitivity with age is lacking, circulating microbial metabolites such as trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) and uremic toxins (e.g., indoxyl sulfate) are postulated to play a role.

Production of TMAO begins with microbial conversion of substrate, most notably choline, to trimethylamine (TMA), which is readily absorbed and quickly converted to TMAO in the liver [82]. In older individuals and clinical populations, elevated levels of TMAO are associated with inflammation and ROS that inhibit eNOS production [83][81][85]. Pertinently, age-related increases in plasma TMAO levels are associated with decreased NO bioavailability and vascular dysfunction [81][85]. For example, in a study by Brunt et al. [81], plasma choline and TMAO levels were inversely related to NO-mediated endothelial-derived dilation [81]. Intriguingly, elevated TMAO levels in old mice are attenuated by antibiotic treatment [83], seemingly through the elimination of known TMAO producers such as select genera from the Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria phyla [82][85]. In comparison, recent work by Hallberg et al. [86] noted that healthy centenarians exhibit a greater abundance of Eubacterium limosum, which have the potential to demethylate TMA, preventing its conversion to circulating TMAO. Mentioned earlier, the uremic toxin indoxyl sulfate may compound TMAO-mediated vascular dysfunction by potentiating ROS production [87]. Synthesis of the above [70][83][81][82][85][87][84][86] highlights how gut dysbiosis and resultant deleterious microbial metabolites, such as TMAO and indoxyl sulfate, may lead to elevated levels of circulating inflammation and ROS, which hinder insulin-mediated skeletal muscle perfusion and impair muscle protein synthetic response to protein feeding with age (Table 1).

It is proposed that GH may not directly influence skeletal muscle anabolism [88][89][90], and instead its effects are mediated through an IGF-1 stimulated anabolic signaling cascade [89][90][91]. Wan et al. [92] noted that piglets fed a low protein diet displayed 50% less serum IGF-1 than those fed a crude protein diet, and also exhibited diminished levels of IGF-1 mRNA expression. Although we were not able to identify any direct comparisons of IGF-1 responses to protein feeding in younger and older humans, Dillon et al. [93] reported that muscle-specific IGF-1 content was increased in healthy older women following 3 months of essential amino acid supplementation. Moreover, several human studies have displayed relationships between habitual protein intake and serum IGF-1 levels [94][95][96]. Collectively, these data provide support for the idea that habitual protein intake influences IGF-1 levels, a finding made relevant by established associations between IGF-1 and both appendicular muscle mass and sarcopenia [97].

The gut microbiome has emerged as a viable mediator of IGF-1 activity. Supporting this notion, Yan et al. [98] demonstrated that conventionalization of GF mice upregulates IGF-1 release, while antibiotic treatment of wild type mice induces IGF-1 downregulation. Moreover, in suckling pigs, faecal microbiota transplantation was associated with an in-crease in GH and IGF-1 levels concurrent with proliferation of Lactobacillus spp. and an increase in the SCFA’s acetate and butyrate [99]. Though the specific microbial species involved in modulating this apparent gut-IGF-1 relationship remain to be determined, Lactobacillus plantarum (L. plantarum) species have garnered support [100][101][102][103]. In a nutrient deficient environment, L. plantarum rescued Drosophila maturation through an apparent upregulation of IGF-1 analogs [100]. Furthermore, monoassociation of GF infant mice in a state of undernutrition with select strains of L. plantarum was demonstrated to be both necessary and sufficient to boost postnatal growth via restoration of GH sensitivity and subsequent hepatic IGF-1 release [101]. More recently, it has also been displayed that postbiotic supplementation of L. plantarum leads to significantly increased total body weight, butyrate abundance, and hepatic mRNA IGF-1 expression in both heat-stressed broiler chickens [102] and post-weaning lambs [103]. Relevantly, associations between advancing age and reductions in Lactobacillus genera are consistently observed [104][105], but unfortunately these works lacked sufficient resolution to confirm a reduction of L. plantarum species. Nevertheless, recent interventional studies show probiotic administration of L. plantarum to fortify mucosal integrity [106] and improve exercise performance (i.e., grip strength and swim endurance) with age [107]. Moreover, a recent systematic review underscored the greater abundance of L. plantarum in healthy long-lived individuals [108], speculatively highlighting the importance of L. plantarum preservation throughout aging. In sum, these studies [100][101][102][103][104][105][106][107][108] provide compelling evidence in support of a role for the gut microbiome, and specifically L. plantarum, in influencing the somatotropic axis and thus, skeletal muscle responsiveness. Due to its relationships with markers of muscle performance and the knowledge that Lactobacilli abundance decreases with age, yet seem to be preserved in heathy centenarians, maintenance of L. plantarum may serve as a therapeutic target in the preservation of muscle mass and avoidance of sarcopenia.

The culmination of this knowledge suggests that GH, and specifically IGF-1, elicit anabolic effects in response to protein intake and exhibit a bidirectional relationship with the gut microbiome (Table 1). Dysregulation of the IGF-1 anabolic signaling cascade and resultant sarcopenia may be caused by dysbiosis of the gut microbiome and depletion of IGF-1-related microbes such as lactobacilli and speculatively L. plantarum. Preservation of these advantageous microbial strains is an area of anabolic resistance research that is deserving of future investigation in human subjects.

4. Intramuscular Signaling

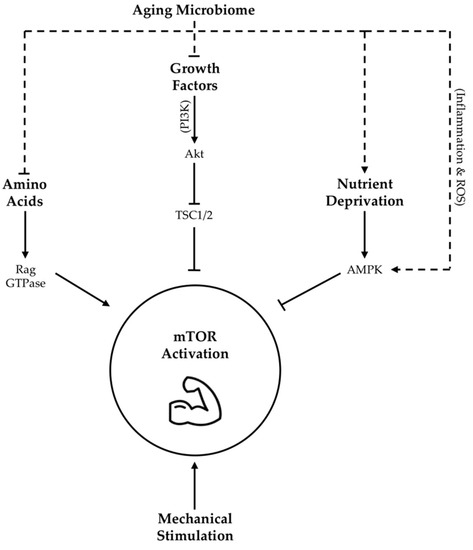

The intricate balance between MPS and MPB, which drives skeletal muscle mass maintenance, is ultimately dictated by underlying molecular mechanisms. One of the most widely accepted mediators of protein synthesis is the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) [109]. mTOR stimulates protein synthesis via two actions: 1) The phosphorylation and inactivation of eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein (4E-BP1), the repressor of mRNA translation, and 2) The phosphorylation and activation of ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K1) [110]. In concert, these molecular events allow protein translation to proceed in an unimpeded fashion. Given the fundamental importance of mTOR signaling in the regulation of MPS, and the demonstrated contribution of down-regulated mTOR activity to aging muscle loss and sarcopenia [111], numerous studies have sought to define the factors underlying mTOR activation. While these investigations have definitively elucidated the role of mechanical stimulation in mTOR regulation, the effects of growth factors and nutrient concentrations on mTOR-mediated protein anabolism warrant more attention.

Growth factors, such as IGF-1, as well as amino acids have been demonstrated to activate mTOR signaling through a complex series of mechanisms [112][113][114][115] outlined in Figure 1. Meanwhile, nutrient deprivation suppresses mTOR activity via phosphorylation and activation of adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK) [116]. Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of nutrient availability and growth factor abundance, both of which may be potently modified by gut microbiota as described above, in arbitrating the molecular regulation of lean tissue mass via mTOR expression (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proposed influence of age-related changes in gut microbiota on skeletal muscle mTOR signaling. Dotted lines indicate hypothesized contribution of aging microbiome changes to upstream regulators of mTOR activity, while solid lines indicate contributions as per literature consensus. TSC1/2 = tuberous sclerosis complex 1/2; Akt = protein kinase B, also abbreviated as PKB; AMPK = adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase; ROS = reactive oxygen species; PI3K = phosphoinositide-3 kinase; GTPase = guanosine triphosphate-ase.

There are many mechanisms through which gut dysbiosis is posited to contribute to muscle aging and sarcopenia. However, an age-related decrease in epithelial integrity and a corresponding increase in circulating lipopolysaccharides (LPS), owing to a reduction in SCFA producing bacteria, evokes inflammatory signaling and a reduction in insulin sensitivity that may be specifically relevant in the context of the mTOR pathway [117]. Firstly, reduced insulin sensitivity detracts from IGF-1 mediated mTOR stimulation [118]. Secondly, elevated LPS levels may be a key determinant of chronic inflammation, which is associated with reduced adaptation of aging skeletal muscle [119]. Mechanistically, increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines are shown to inhibit the mTOR pathway through the activation of AMPK [120][121][122] (Figure 1). Amplifying LPS-mediated inflammatory burden, age-associated ROS over-production may also blunt mTOR signaling [123]. Intriguingly, a mechanism by which enteric microbiota may influence ROS generation has also been proposed [124]. Moreover, communication between dysbiotic microbial communities and mitochondria [125] may exacerbate mitochondrial ROS generation with age. Collectively, these data suggest that adverse changes in the microbiome seen with age contribute to elevated levels of circulating inflammation and ROS that are demonstrated to impair MPS via suppression of skeletal muscle mTOR signaling (Figure 1). However, it is interesting to note that LPS stimulation seems to evoke less of an inflammatory response in long-lived compared to normally age mice [126], alluding to the importance of heightened antioxidant defense mechanisms as a characteristic of highly successful aging.

References

- Koopman, R.; Walrand, S.; Beelen, M.; Gijsen, A.P.; Kies, A.K.; Boirie, Y.; Saris, W.H.M.; Van Loon, L.J.C. Dietary Protein Digestion and Absorption Rates and the Subsequent Postprandial Muscle Protein Synthetic Response Do Not Differ between Young and Elderly Men. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1707–1713.

- Gibson, J.A.; Sladen, G.E.; Dawson, A.M. Protein absorption and ammonia production: The effects of dietary protein and removal of the colon. Br. J. Nutr. 1976, 35, 61–65.

- Fan, P.; Li, L.; Rezaei, A.; Eslamfam, S.; Che, D.; Ma, X. Metabolites of Dietary Protein and Peptides by Intestinal Microbes and their Impacts on Gut. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2015, 16, 646–654.

- Dangin, M.; Boirie, Y.; Garcia-Rodenas, C.; Gachon, P.; Fauquant, J.; Callier, P.; Ballèvre, O.; Beaufrère, B. The digestion rate of protein is an independent regulating factor of postprandial protein retention. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2001, 280, E340–E348.

- Gibson, N.R.; Fereday, A.; Cox, M.; Halliday, D.; Pacy, P.J.; Millward, D.J. Influences of dietary energy and protein on leucine kinetics during feeding in healthy adults. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 1996, 270, E282–E291.

- Dangin, M.; Guillet, C.; Garcia-Rodenas, C.; Gachon, P.; Bouteloup-Demange, C.; Reiffers-Magnani, K.; Fauquant, J.; Ballèvre, O.; Beaufrère, B. The Rate of Protein Digestion affects Protein Gain Differently during Aging in Humans. J. Physiol. 2003, 549, 635–644.

- Milan, A.M.; D’Souza, R.F.; Pundir, S.; Pileggi, C.A.; Barnett, M.P.G.; Markworth, J.F.; Cameronsmith, D.; Mitchell, C.J. Older adults have delayed amino acid absorption after a high protein mixed breakfast meal. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2015, 19, 839–845.

- Cani, P.D.; Possemiers, S.; Van De Wiele, T.; Guiot, Y.; Everard, A.; Rottier, O.; Geurts, L.; Naslain, D.; Neyrinck, A.; Lambert, D.M.; et al. Changes in gut microbiota control inflammation in obese mice through a mechanism involving GLP-2-driven improvement of gut permeability. Gut 2009, 58, 1091–1103.

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Brown, M.A.; Qiao, S. Dietary Protein and Gut Microbiota Composition and Function. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2018, 20, 145–154.

- Willing, B.P.; Van Kessel, A.G. Intestinal microbiota differentially affect brush border enzyme activity and gene expression in the neonatal gnotobiotic pig. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2009, 93, 586–595.

- Kozakova, H.; Kolinska, J.; Lojda, Z.; Rehakova, Z.; Sinkora, J.; Zákostelecká, M.; Šplíchal, I.; Tlaskalova-Hogenova, H. Effect of bacterial monoassociation on brush-border enzyme activities in ex-germ-free piglets: Comparison of commensal and pathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Microbes Infect. 2006, 8, 2629–2639.

- Raul, F.; Gosse, F.; Doffoel, M.; Darmenton, P.; Wessely, J.Y. Age related increase of brush border enzyme activities along the small intestine. Gut 1988, 29, 1557–1563.

- Feldman, M.; Cryer, B.; McArthur, K.E.; Huet, B.A.; Lee, E. Effects of aging and gastritis on gastric acid and pepsin secretion in humans: A prospective study. Gastroenterology 1996, 110, 1043–1052.

- Diether, N.E.; Willing, B.P. Microbial Fermentation of Dietary Protein: An Important Factor in Diet–Microbe–Host Interaction. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 19.

- Enoki, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Arake, R.; Sugimoto, R.; Imafuku, T.; Tominaga, Y.; Ishima, Y.; Kotani, S.; Nakajima, M.; Tanaka, M.; et al. Indoxyl sulfate potentiates skeletal muscle atrophy by inducing the oxidative stress-mediated expression of myostatin and atrogin-1. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32084.

- Wyczalkowska-Tomasik, A.; Czarkowska-Paczek, B.; Giebultowicz, J.; Wroczynski, P.; Paczek, L. Age-dependent increase in serum levels of indoxyl sulphate and p-cresol sulphate is not related to their precursors: Tryptophan and tyrosine. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2016, 17, 1022–1026.

- Dallas, D.C.; Sanctuary, M.R.; Qu, Y.; Khajavi, S.H.; Van Zandt, A.E.; Dyandra, M.; Frese, S.A.; Barile, D.; German, J.B. Personalizing protein nourishment. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3313–3331.

- Marchesi, J.R.; Adams, D.H.; Fava, F.; Hermes, G.D.A.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Hold, G.; Quraishi, M.N.; Kinross, J.; Smidt, H.; Tuohy, K.M.; et al. The gut microbiota and host health: A new clinical frontier. Gut 2016, 65, 330–339.

- Frampton, J.; Murphy, K.G.; Frost, G.; Chambers, E.S. Short-chain fatty acids as potential regulators of skeletal muscle metabolism and function. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 840–848.

- Walsh, M.E.; Bhattacharya, A.; Sataranatarajan, K.; Qaisar, R.; Sloane, L.B.; Rahman, M.M.; Kinter, M.; Van Remmen, H. The histone deacetylase inhibitor butyrate improves metabolism and reduces muscle atrophy during aging. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 957–970.

- Lahiri, S.; Kim, H.; Garcia-Perez, I.; Reza, M.M.; Martin, K.A.; Kundu, P.; Cox, L.M.; Selkrig, J.; Posma, J.M.; Zhang, H.; et al. The gut microbiota influences skeletal muscle mass and function in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaan5662.

- Peng, L.; Li, Z.-R.; Green, R.S.; Holzman, I.R.; Lin, J. Butyrate Enhances the Intestinal Barrier by Facilitating Tight Junction Assembly via Activation of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase in Caco-2 Cell Monolayers. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1619–1625.

- Mach, N.; Fuster-Botella, D. Endurance exercise and gut microbiota: A review. J. Sport Health Sci. 2017, 6, 179–197.

- Rampelli, S.; Candela, M.; Turroni, S.; Biagi, E.; Collino, S.; Franceschi, C.; O’Toole, P.W.; Brigidi, P. Functional metagenomic profiling of intestinal microbiome in extreme ageing. Aging 2013, 5, 902–912.

- Debebe, T.; Biagi, E.; Soverini, M.; Holtze, S.; Hildebrandt, T.B.; Birkemeyer, C.; Wyohannis, D.; Lemma, A.; Brigidi, P.; Savkovic, V.; et al. Unraveling the gut microbiome of the long-lived naked mole-rat. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9590.

- Kong, F.; Hua, Y.; Zeng, B.; Ning, R.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J. Gut microbiota signatures of longevity. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, R832–R833.

- Wu, L.; Zeng, T.; Zinellu, A.; Rubino, S.; Kelvin, D.J.; Carru, C. A Cross-Sectional Study of Compositional and Functional Profiles of Gut Microbiota in Sardinian Centenarians. mSystems 2019, 4, e00325-19.

- Boirie, Y.; Dangin, M.; Gachon, P.; Vasson, M.-P.; Maubois, J.-L.; Beaufrère, B. Slow and fast dietary proteins differently modulate postprandial protein accretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 14930–14935.

- Deer, R.R.; Volpi, E. Protein intake and muscle function in older adults. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2015, 18, 248–253.

- Raj, T.; Dileep, U.; Vaz, M.; Fuller, M.F.; Kurpad, A.V. Intestinal Microbial Contribution to Metabolic Leucine Input in Adult Men. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 2217–2221.

- Metges, C.C. Contribution of Microbial Amino Acids to Amino Acid Homeostasis of the Host. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1857S–1864S.

- Arboleya, S.; Watkins, C.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P. Gut Bifidobacteria Populations in Human Health and Aging. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1204.

- Wang, F.; Huang, G.; Cai, D.; Li, D.; Liang, X.; Yu, T.; Shen, P.; Su, H.; Liu, J.; Gu, H.; et al. Qualitative and Semiquantitative Analysis of Fecal Bifidobacterium Species in Centenarians Living in Bama, Guangxi, China. Curr. Microbiol. 2015, 71, 143–149.

- Biagi, E.; Franceschi, C.; Rampelli, S.; Severgnini, M.; Ostan, R.; Turroni, S.; Consolandi, C.; Quercia, S.; Scurti, M.; Monti, D.; et al. Gut Microbiota and Extreme Longevity. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 1480–1485.

- Wang, N.; Li, R.; Lin, H.; Fu, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Su, M.; Huang, P.; Qian, J.; Jiang, F.; et al. Enriched taxa were found among the gut microbiota of centenarians in East China. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222763.

- Kim, B.-S.; Choi, C.W.; Shin, H.; Jin, S.-P.; Bae, J.-S.; Han, M.; Seo, E.Y.; Chun, J.; Chung, J.H. Comparison of the Gut Microbiota of Centenarians in Longevity Villages of South Korea with Those of Other Age Groups. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 429–440.

- Matteuzzi, D.; Crociani, F.; Emaldi, O. Amino acids produced by bifidobacteria and some Clostridia. Ann. Microbiol. 1978, 129, 175–181.

- Sauer, F.D.; Erfle, J.D.; Mahadevan, S. Amino acid biosynthesis in mixed rumen cultures. Biochem. J. 1975, 150, 357–372.

- Torrallardona, D.; Harris, C.I.; Coates, M.E.; Fuller, M.F. Microbial amino acid synthesis and utilization in rats: Incorporation of15N from15NH4Cl into lysine in the tissues of germ-free and conventional rats. Br. J. Nutr. 1996, 76, 689–700.

- Metges, C.C.; El-Khoury, A.E.; Henneman, L.; Petzke, K.J.; Grant, I.; Bedri, S.; Pereira, P.P.; Ajami, A.M.; Fuller, M.F.; Young, V.R. Availability of intestinal microbial lysine for whole body lysine homeostasis in human subjects. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 1999, 277, E597–E607.

- Tesseraud, S.; Peresson, R.; Lopes, J.; Chagneau, A. Dietary lysine deficiency greatly affects muscle and liver protein turnover in growing chickens. Br. J. Nutr. 1996, 75, 853–865.

- Cheng, S.; Larson, M.G.; McCabe, E.L.; Murabito, J.M.; Rhee, E.P.; Ho, J.E.; Jacques, P.F.; Ghorbani, A.; Magnusson, M.; Souza, A.L.; et al. Distinct metabolomic signatures are associated with longevity in humans. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6791.

- Saraswati, S.; Sitaraman, R. Aging and the human gut microbiota—from correlation to causality. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 764.

- Petersen, L.M.; Bautista, E.J.; Nguyen, H.; Hanson, B.M.; Chen, L.; Lek, S.H.; Sodergren, E.; Weinstock, G.M. Community characteristics of the gut microbiomes of competitive cyclists. Microbiome 2017, 5, 98.

- Van Tongeren, S.P.; Slaets, J.P.J.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Welling, G.W.; Viterbo, A.; Harel, M.; Horwitz, B.A.; Chet, I.; Mukherjee, P.K. Fecal Microbiota Composition and Frailty. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 6241–6246.

- Claesson, M.J.; Jeffery, I.B.; Conde, S.; Power, S.E.; O’Connor, E.M.; Cusack, S.; Harris, H.M.B.; Coakley, M.; Lakshminarayanan, B.; O’Sullivan, O.; et al. Gut microbiota composition correlates with diet and health in the elderly. Nature 2012, 488, 178–184.

- Blomstrand, E.; Eliasson, J.; Karlsson, H.K.R.; Köhnke, R. Branched-Chain Amino Acids Activate Key Enzymes in Protein Synthesis after Physical Exercise. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 269S–273S.

- Neis, E.P.J.G.; DeJong, C.H.C.; Rensen, S.S. The Role of Microbial Amino Acid Metabolism in Host Metabolism. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2930–2946.

- Volpi, E.; Mittendorfer, B.; Wolf, S.E.; Wolfe, R.R. Oral amino acids stimulate muscle protein anabolism in the elderly despite higher first-pass splanchnic extraction. Am. J. Physiol. Content 1999, 277, E513–E520.

- Jourdan, M.; Cynober, L.; Moinard, C.; Blanc, M.C.; Neveux, N.; De Bandt, J.P.; Aussel, C. Splanchnic sequestration of amino acids in aged rats: In vivo and ex vivo experiments using a model of isolated perfused liver. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2008, 294, R748–R755.

- Boirie, Y.; Gachon, P.; Beaufrère, B. Splanchnic and whole-body leucine kinetics in young and elderly men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 65, 489–495.

- Stoll, B.; Burrin, D.G. Measuring splanchnic amino acid metabolism in vivo using stable isotopic tracers1,2. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 84, E60–E72.

- Kullman, E.L.; Campbell, W.W.; Krishnan, R.K.; Yarasheski, K.E.; Evans, W.J.; Kirwan, J.P. Age Attenuates Leucine Oxidation after Eccentric Exercise. Int. J. Sports Med. 2013, 34, 695–699.

- Kurpad, A.V.; Jahoor, F.; Borgonha, S.; Poulo, S.; Rekha, S.; Fjeld, C.R.; Reeds, P.J. A minimally invasive tracer protocol is effective for assessing the response of leucine kinetics and oxidation to vaccination in chronically energy-deficient adult males and children. J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 1537–1544.

- He, F.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Isolauri, E.; Hosoda, M.; Benno, Y.; Salminen, S. Differences in Composition and Mucosal Adhesion of Bifidobacteria Isolated from Healthy Adults and Healthy Seniors. Curr. Microbiol. 2001, 43, 351–354.

- Gonzalez, A.M.; Hoffman, J.R.; Stout, J.R.; Fukuda, D.H.; Willoughby, D.S. Intramuscular Anabolic Signaling and Endocrine Response Following Resistance Exercise: Implications for Muscle Hypertrophy. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 671–685.

- Wilkinson, S.B.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Grant, E.J.; Correia, C.E.; Phillips, S.M. Hypertrophy with unilateral resistance exercise occurs without increases in endogenous anabolic hormone concentration. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2006, 98, 546–555.

- Spiering, B.A.; Kraemer, W.J.; Anderson, J.M.; Armstrong, L.E.; Nindl, B.C.; Volek, J.S.; Judelson, D.A.; Joseph, M.; Vingren, J.L.; Hatfield, D.L.; et al. Effects of Elevated Circulating Hormones on Resistance Exercise-Induced Akt Signaling. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, 1039–1048.

- West, D.W.D.; Kujbida, G.W.; Moore, D.R.; Atherton, P.; Burd, N.A.; Padzik, J.P.; De Lisio, M.; Tang, J.E.; Parise, G.; Rennie, M.J.; et al. Resistance exercise-induced increases in putative anabolic hormones do not enhance muscle protein synthesis or intracellular signalling in young men. J. Physiol. 2009, 587, 5239–5247.

- Phillips, S.M. Insulin and muscle protein turnover in humans: Stimulatory, permissive, inhibitory, or all of the above? Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2008, 295, E731.

- Srikanthan, P.; Hevener, A.L.; Karlamangla, A.S. Sarcopenia Exacerbates Obesity-Associated Insulin Resistance and Dysglycemia: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10805.

- Guillet, C.; Boirie, Y. Insulin resistance: A contributing factor to age-related muscle mass loss? Diabetes Metab. 2005, 31, 5S20–5S26.

- Toogood, A.A. Growth hormone (GH) status and body composition in normal ageing and in elderly adults with GH deficiency. Horm. Res. 2003, 60, 105–111.

- Russell-Aulet, M.; Dimaraki, E.V.; Jaffe, C.A.; DeMott-Friberg, R.; Barkan, A.L. Aging-related growth hormone (GH) decrease is a selective hypothalamic GH-releasing hormone pulse amplitude mediated phenomenon. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Boil. Sci. Med Sci. 2001, 56, M124–M129.

- Cappola, A.R.; Xue, Q.-L.; Fried, L.P. Multiple Hormonal Deficiencies in Anabolic Hormones Are Found in Frail Older Women: The Women’s Health and Aging Studies. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Boil. Sci. Med Sci. 2009, 64, 243–248.

- Finkelstein, J.W.; Roffwarg, H.P.; Boyar, R.M.; Kream, J.; Hellman, L. Age-Related Change in the Twenty-Four Hour Spontaneous Secretion of Growth Hormone. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1972, 35, 665–670.

- Waters, D.L.; Yau, C.L.; Montoya, G.D.; Baumgartner, R.N. Serum Sex Hormones, IGF-1, and IGFBP3 Exert a Sexually Dimorphic Effect on Lean Body Mass in Aging. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Boil. Sci. Med. Sci. 2003, 58, M648–M652.

- Huang, S.; Czech, M.P. The GLUT4 Glucose Transporter. Cell Metab. 2007, 5, 237–252.

- Dillon, E.L. Nutritionally essential amino acids and metabolic signaling in aging. Amino Acids 2013, 45, 431–441.

- Battson, M.L.; Lee, D.M.; Jarrell, D.K.; Hou, S.; Ecton, K.E.; Weir, T.L.; Gentile, C.L. Suppression of gut dysbiosis reverses Western diet-induced vascular dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2018, 314, E468–E477.

- Rasmussen, B.B.; Fujita, S.; Wolfe, R.R.; Mittendorfer, B.; Roy, M.; Rowe, V.L.; Volpi, E. Insulin resistance of muscle protein metabolism in aging. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 768–769.

- Scherrer, U.; Randin, D.; Vollenweider, P.; Vollenweider, L.; Nicod, P. Nitric oxide release accounts for insulin’s vascular effects in humans. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 94, 2511–2515.

- Petrie, J.R.; Ueda, S.; Webb, D.J.; Elliott, H.L.; Connell, J.M. Endothelial Nitric Oxide Production and Insulin Sensitivity. Circulation 1996, 93, 1331–1333.

- Rajapakse, N.W.; Chong, A.L.; Zhang, W.Z.; Kaye, D.M. Insulin-mediated activation of the L-arginine nitric oxide pathway in man, and its impairment in diabetes. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61840.

- Williams, S.B.; Cusco, J.A.; Roddy, M.-A.; Johnstone, M.T.; Creager, M.A. Impaired nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1996, 27, 567–574.

- Clark, M.G.; Wallis, M.G.; Barrett, E.J.; Vincent, M.A.; Richards, S.M.; Clerk, L.H.; Rattigan, S. Blood flow and muscle metabolism: A focus on insulin action. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2003, 284, E241–E258.

- Seals, D.R.; Jablonski, K.L.; Donato, A.J. Aging and vascular endothelial function in humans. Clin. Sci. 2011, 120, 357–375.

- Fujita, S.; Rasmussen, B.B.; Cadenas, J.G.; Grady, J.J.; Volpi, E. Effect of insulin on human skeletal muscle protein synthesis is modulated by insulin-induced changes in muscle blood flow and amino acid availability. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2006, 291, E745–E754.

- Nygren, J.; Nair, K.S. Differential Regulation of Protein Dynamics in Splanchnic and Skeletal Muscle Beds by Insulin and Amino Acids in Healthy Human Subjects. Diabetes 2003, 52, 1377–1385.

- Steinberg, H.O.; Brechtel, G.; Johnson, A.; Fineberg, N.; Baron, A.D. Insulin-mediated skeletal muscle vasodilation is nitric oxide dependent. A novel action of insulin to increase nitric oxide release. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 94, 1172–1179.

- Brunt, V.E.; Gioscia-Ryan, R.A.; Casso, A.G.; Vandongen, N.S.; Ziemba, B.P.; Sapinsley, Z.J.; Richey, J.J.; Zigler, M.C.; Neilson, A.P.; Davy, K.P.; et al. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Promotes Age-Related Vascular Oxidative Stress and Endothelial Dysfunction in Mice and Healthy Humans. Hypertension 2020, 76, 101–112.

- Janeiro, M.H.; Ramírez, M.J.; Milagro, F.I.; Martínez, J.A.; Solas, M. Implication of Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) in Disease: Potential Biomarker or New Therapeutic Target. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1398.

- Brunt, V.E.; Gioscia-Ryan, R.A.; Richey, J.J.; Zigler, M.C.; Cuevas, L.M.; Gonzalez, A.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Battson, M.L.; Smithson, A.T.; Gilley, A.D.; et al. Suppression of the gut microbiome ameliorates age-related arterial dysfunction and oxidative stress in mice. J. Physiol. 2019, 597, 2361–2378.

- Fransen, F.; Van Beek, A.A.; Borghuis, T.; El Aidy, S.; Hugenholtz, F.; Jongh, C.V.D.G.-D.; Savelkoul, H.F.J.; De Jonge, M.I.; Boekschoten, M.V.; Smidt, H.; et al. Aged Gut Microbiota Contributes to Systemical Inflammaging after Transfer to Germ-Free Mice. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1385.

- Liu, Y.; Dai, M. Trimethylamine N-Oxide Generated by the Gut Microbiota Is Associated with Vascular Inflammation: New Insights into Atherosclerosis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 4634172.

- Hallberg, Z.F.; Taga, M.E. Taking the “Me” out of meat: A new demethylation pathway dismantles a toxin’s precursor. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 11982–11983.

- Tumur, Z.; Niwa, T. Indoxyl Sulfate Inhibits Nitric Oxide Production and Cell Viability by Inducing Oxidative Stress in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Am. J. Nephrol. 2009, 29, 551–557.

- Rennie, M.J. Claims for the anabolic effects of growth hormone: A case of the Emperor’s new clothes? Br. J. Sports Med. 2003, 37, 100–105.

- Velloso, C.P. Regulation of muscle mass by growth hormone and IGF-I. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 154, 557–568.

- Chikani, V.; Ho, K.K.Y. Action of GH on skeletal muscle function: Molecular and metabolic mechanisms. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 52, R107–R123.

- Bodine, S.C.; Stitt, T.N.; Gonzalez, M.; Kline, W.O.; Stover, G.L.; Bauerlein, R.; Zlotchenko, E.; Scrimgeour, A.; Lawrence, J.C.; Glass, D.J.; et al. Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 3, 1014–1019.

- Wan, X.; Wang, S.; Xu, J.; Zhuang, L.; Xing, K.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, X.; Wang, L.; Gao, P.; Xi, Q.; et al. Dietary protein-induced hepatic IGF-1 secretion mediated by PPARγ activation. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173174.

- Dillon, E.L.; Sheffield-Moore, M.; Paddon-Jones, U.; Gilkison, C.; Sanford, A.P.; Casperson, S.L.; Jiang, J.; Chinkes, D.L.; Urban, R.J. Amino Acid Supplementation Increases Lean Body Mass, Basal Muscle Protein Synthesis, and Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Expression in Older Women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 1630–1637.

- Crowe, F.L.; Key, T.J.; Allen, N.E.; Appleby, P.N.; Roddam, A.; Overvad, K.; Grønbaek, H.; Tjønneland, A.; Halkjaer, J.; Dossus, L.; et al. The Association between Diet and Serum Concentrations of IGF-I, IGFBP-1, IGFBP-2, and IGFBP-3 in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009, 18, 1333–1340.

- Fontana, L.; Weiss, E.P.; Villareal, D.T.; Klein, S.; Holloszy, J.O. Long-term effects of calorie or protein restriction on serum IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 concentration in humans. Aging Cell 2008, 7, 681–687.

- Larsson, S.C.; Wolk, K.; Brismar, K.; Wolk, A. Association of diet with serum insulin-like growth factor I in middle-aged and elderly men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 1163–1167.

- Bian, A.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, X.; Guo, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Association between sarcopenia and levels of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 in the elderly. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2020, 21, 214.

- Yan, J.; Herzog, J.W.; Tsang, K.; Brennan, C.A.; Bower, M.A.; Garrett, W.S.; Sartor, B.R.; Aliprantis, A.O.; Charles, J.F. Gut microbiota induce IGF-1 and promote bone formation and growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E7554–E7563.

- Cheng, C.S.; Wei, H.K.; Wang, P.; Yu, H.C.; Zhang, X.M.; Jiang, S.W.; Peng, J. Early intervention with faecal microbiota transplantation: An effective means to improve growth performance and the intestinal development of suckling piglets. Animal 2019, 13, 533–541.

- Storelli, G.; Defaye, A.; Erkosar, B.; Hols, P.; Royet, J.; Leulier, F. Lactobacillus plantarum Promotes Drosophila Systemic Growth by Modulating Hormonal Signals through TOR-Dependent Nutrient Sensing. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 403–414.

- Schwarzer, M.; Makki, K.; Storelli, G.; Machuca-Gayet, I.; Srutkova, D.; Hermanova, P.; Martino, M.E.; Balmand, S.; Hudcovic, T.; Heddi, A.; et al. Lactobacillus plantarum strain maintains growth of infant mice during chronic undernutrition. Science 2016, 351, 854–857.

- Humam, A.M.; Loh, T.C.; Foo, H.L.; Samsudin, A.A.; Mustapha, N.M.; Zulkifli, I.; Izuddin, W.I. Effects of Feeding Different Postbiotics Produced by Lactobacillus plantarum on Growth Performance, Carcass Yield, Intestinal Morphology, Gut Microbiota Composition, Immune Status, and Growth Gene Expression in Broilers under Heat Stress. Animals 2019, 9, 644.

- Izuddin, W.I.; Loh, T.C.; Samsudin, A.A.; Foo, H.L.; Humam, A.M.; Shazali, N. Effects of postbiotic supplementation on growth performance, ruminal fermentation and microbial profile, blood metabolite and GHR, IGF-1 and MCT-1 gene expression in post-weaning lambs. BMC Veter. Res. 2019, 15, 315.

- Woodmansey, E. Intestinal bacteria and ageing. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 102, 1178–1186.

- Hopkins, M.J.; Sharp, R.; Macfarlane, G.T. Age and disease related changes in intestinal bacterial populations assessed by cell culture, 16S rRNA abundance, and community cellular fatty acid profiles. Gut 2001, 48, 198–205.

- Van Beek, A.A.; Sovran, B.; Hugenholtz, F.; Meijer, B.; Hoogerland, J.A.; Mihailova, V.; Van Der Ploeg, C.; Belzer, C.; Boekschoten, M.V.; Hoeijmakers, J.H.J.; et al. Supplementation with Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 Prevents Decline of Mucus Barrier in Colon of Accelerated Aging Ercc1−/Δ7 Mice. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 408.

- Chen, Y.M.; Wei, L.; Chiu, Y.S.; Hsu, Y.J.; Tsai, T.Y.; Wang, M.F.; Huang, C.C. Lactobacillus plantarum TWK10 supplementation improves exercise performance and increases muscle mass in mice. Nutrients 2016, 8, 205.

- Badal, V.D.; Vaccariello, E.D.; Murray, E.R.; Yu, K.E.; Knight, R.; Jeste, D.V.; Nguyen, T.T. The Gut Microbiome, Aging, and Longevity: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3759.

- Goodman, C.A.; Frey, J.W.; Mabrey, D.M.; Jacobs, B.L.; Lincoln, H.C.; You, J.-S.; Hornberger, T.A. The role of skeletal muscle mTOR in the regulation of mechanical load-induced growth. J. Physiol. 2011, 589, 5485–5501.

- Hay, N.; Sonenberg, N. Upstream and Downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 1926–1945.

- Yoon, M.-S. mTOR as a Key Regulator in Maintaining Skeletal Muscle Mass. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 788.

- Nobukuni, T.; Joaquin, M.; Roccio, M.; Dann, S.G.; Kim, S.Y.; Gulati, P.; Byfield, M.P.; Backer, J.M.; Natt, F.; Bos, J.L.; et al. Amino acids mediate mTOR/raptor signaling through activation of class 3 phosphatidylinositol 3OH-kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 14238–14243.

- Reiling, J.H.; Sabatini, D.M. Stress and mTORture signaling. Oncogene 2006, 25, 6373–6383.

- Huang, J.; Manning, B.D. The TSC1–TSC2 complex: A molecular switchboard controlling cell growth. Biochem. J. 2008, 412, 179–190.

- Inoki, K.; Zhu, T.; Guan, K.-L. TSC2 Mediates Cellular Energy Response to Control Cell Growth and Survival. Cell 2003, 115, 577–590.

- Kimball, S.R. Interaction between the AMP-Activated Protein Kinase and mTOR Signaling Pathways. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006, 38, 1958–1964.

- Grosicki, G.J.; Fielding, R.A.; Lustgarten, M.S. Gut Microbiota Contribute to Age-Related Changes in Skeletal Muscle Size, Composition, and Function: Biological Basis for a Gut-Muscle Axis. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2018, 102, 433–442.

- Friedrich, N.; Thuesen, B.; Jørgensen, T.; Juul, A.; Spielhagen, C.; Wallaschofksi, H.; Linneberg, A. The Association Between IGF-I and Insulin Resistance: A general population study in Danish adults. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 768–773.

- Grosicki, G.J.; Barrett, B.B.; Englund, D.A.; Liu, C.; Travison, T.G.; Cederholm, T.; Koochek, A.; Von Berens, Å.; Gustafsson, T.; Benard, T.; et al. Circulating Interleukin-6 Is Associated with Skeletal Muscle Strength, Quality, and Functional Adaptation with Exercise Training in Mobility-Limited Older Adults. J. Frailty Aging 2020, 9, 57–63.

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976.

- Dalle, S.; Rossmeislova, L.; Koppo, K. The Role of Inflammation in Age-Related Sarcopenia. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 1045.

- Frost, R.A.; Lang, C.H. mTor Signaling in Skeletal Muscle During Sepsis and Inflammation: Where Does It All Go Wrong? Physiology 2011, 26, 83–96.

- Damiano, S.; Muscariello, E.; La Rosa, G.; Di Maro, M.; Mondola, P.; Santillo, M. Dual Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Muscle Function: Can Antioxidant Dietary Supplements Counteract Age-Related Sarcopenia? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3815.

- Mercante, J.W.; Neish, A.S. Reactive Oxygen Production Induced by the Gut Microbiota: Pharmacotherapeutic Implications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 1519–1529.

- Clark, A.; Mach, N. The Crosstalk between the Gut Microbiota and Mitochondria during Exercise. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 319.

- Arranz, L.; Lord, J.M.; De La Fuente, M. Preserved ex vivo inflammatory status and cytokine responses in naturally long-lived mice. AGE 2010, 32, 451–466.