| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Young Joon Cho | + 940 word(s) | 940 | 2021-03-04 05:28:57 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | -253 word(s) | 687 | 2021-03-09 06:46:42 | | |

Video Upload Options

Charge transporting materials (CTMs) in perovskite solar cells (PSCs) have played an important role in improving the stability by replacing the liquid electrolyte with solid state electron or hole conductors and enhancing the photovoltaic efficiency by the efficient electron collection. Many organic and inorganic materials for charge transporting in PSCs have been studied and applied to increase the charge extraction, transport and collection, such as Spiro-OMeTAD for hole transporting material (HTM), TiO2 for electron transporting material (ETM) and MoOX for HTM etc. However, recently inorganic CTMs are used to replace the disadvantages of organic materials in PSCs such as, the long-term operational instability, low charge mobility. Especially, atomic layer deposition (ALD) has many advantages in obtaining the conformal, dense and virtually pinhole-free layers.

1. Introduction

Presently, perovskite solar cells (PSCs) are one of the most outstanding devices using the solar cell technology, and their conversion efficiency has reached 25.5% in case of single-junction perovskite cells and 29.1% for perovskite/Si tandem cells [1]. Although PSCs have almost overtaken Si solar cells in terms of power conversion efficiency, the commercialization of PSCs is inhibited by several problems, such as the long-term stability and the large-scale fabrication issues. PSCs can be an alternative to the other solar cells if they are cheaper and more efficient with guaranteed long-term stability. Current manufacturers of photovoltaic (PV) modules provide a warranty for lost power replacement with power output of 90% after a decade and of 80% at the end of the warranty, which corresponds to less than 1% power loss per year [2]. The degradation of PSCs is known to be caused by oxygen and moisture, UV light, solution processing and thermal effects [3]. These factors react with the perovskite layers, such as the perovskite absorption layer, buffer layer, electron transporting layer (ETL) and hole transporting layer (HTL). This results in the decomposition of the perovskite absorber, non-stoichiometry defects, which are related to oxygen vacancies and titanium interstitials [4]. The traditional dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) dye-sensitized and infiltrated a porous TiO2 with a liquid electrolyte. This inherent instability in devices has been solved by replacing the liquid with the organic–inorganic metal halide materials, such as CH3NH3PbBr3 and CH3NH3PbI3 and as a result, the stability and the power conversion efficiency has been improved rapidly over a relatively short time. By replacing the liquid electrolyte with the organic–inorganic metal halide, the ETL and HTL have been investigated to reduce the degradation of organic ETL and HTL.

2. Perovskite Solar Cells

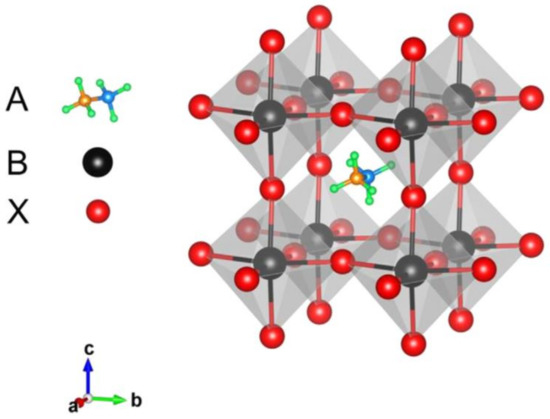

Perovskites had been well-known in the scientific community for over a century before they were used as solar cell absorbers. The first natural perovskite was discovered by the mineralogist Gustav Rose in 1839 and perovskites, which have the chemical formula ABX3, adopt the same crystal structure as CaTiO3. PSCs historically originate from DSSCs [5] and over decades the efficiency of PSCs has been enhanced considerably by the organic–inorganic metal halide materials. Metal halide perovskites have a direct band gap and strong light-absorption properties, high charge-carrier mobility, and small exciton binding energy [6]. These halide materials with the formula of ABX3 consist of three ion parts, the organic cation (A), the metallic cation (B), and halide ion (X), as shown in Figure 1 [7]. Methylammonium CH3NH3+, formamidinium HC(NH2)2+ and cesium (Cs+) are the materials used as the cations in perovskite absorbers and Pb2+, Sn2+, and Ge2+ are the metal cations. I−, Cl−, and Br− are used as the halide ions. The combination of these materials shows various properties and solar cell performances [7][8][9]. Recently, organic–inorganic hybrid metal halides are emerging as perovskite absorber materials. But the structure and physical properties of CH3NH3MX3, which is a type of perovskites, were first reported by Weber in 1978 [10] and these organic–inorganic perovskite materials, such as (C4H9NH3)2(CH3NH3)n−1SnnI3n+1, have been highlighted as high-temperature superconductor materials. These materials can be transformed into metal by inserting more inorganic layers; however, in the 1990s little attention was paid to them as solar cell absorbers [11].

Figure 1. Crystal structure of an organic–inorganic metal halide perovskite. Reproduced with permission from Reference [7].

References

- NREL. Best Research Efficiency. Available online: (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Roesch, R.; Faber, T.; Von Hauff, E.; Brown, T.M.; Lira-Cantu, M.; Hoppe, H. Procedures and practices for evaluating thin-film solar cell stability. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1501407.

- Niu, G.; Guo, X.; Wang, L. Review of recent progress in chemical stability of perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 8970–8980.

- Pathak, S.K.; Abate, A.; Ruckdeschel, P.; Roose, B.; Gödel, K.C.; Vaynzof, Y.; Santhala, A.; Watanabe, S.-I.; Hollman, D.J.; Noel, N.; et al. Performance and Stability Enhancement of Dye-Sensitized and Perovskite Solar Cells by Al Doping of TiO2. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 6046–6055.

- Grätzel, M. The light and shade of perovskite solar cells. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 838–842.

- Calió, L.; Kazim, S.; Grätzel, M.; Ahmad, S. Hole-Transport Materials for Perovskite Solar Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 14522–14545.

- Wang, D.; Wright, M.; Elumalai, N.K.; Uddin, A. Stability of perovskite solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 147, 255–275.

- Zuo, C.; Bolink, H.J.; Han, H.; Huang, J.; Cahen, D.; Ding, L. Advances in Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Sci. 2016, 3, 1500324.

- Wehrenfennig, C.; Eperon, G.E.; Johnston, M.B.; Snaith, H.J.; Herz, L.M. High Charge Carrier Mobilities and Lifetimes in Organolead Trihalide Perovskites. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 1584–1589.

- Weber, D. CH3NH3PbX3, ein Pb(II)-System mit kubischer Perowskitstruktur / CH3NH3PbX3, a Pb(II)-System with Cubic Perovskite Structure. Z. Naturforsch. B 1978, 33, 1443–1445.

- Mitzi, D.B.; Feild, C.A.; Harrison, W.T.A.; Guloy, A.M. Conducting tin halides with a layered organic-based perovskite structure. Nature 1994, 369, 467–469.