| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alexia VINEL | + 3902 word(s) | 3902 | 2021-03-02 04:14:26 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 3902 | 2021-03-18 03:39:19 | | |

Video Upload Options

Estrogens are key regulators of bone turnover in both females and males. These hormones play a major role in longitudinal and width growth throughout puberty as well as in the regulation of bone turnover. Effects of estrogens on bone involve either estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) or beta (ERβ) depending on the type of bone (femur, vertebrae, tibia, mandible), the compartment (trabecular or cortical), cell types involved (osteoclasts, osteoblasts and osteocytes) and the sex.

1. Estrogen Receptors

Estrogen effects are mediated by two receptors, estrogen receptors alpha (ERα) and beta (ERβ). Encoded by gene esr1 and cloned in 1986, ERα has been considered as the unique receptor for estrogens until the discovery and cloning of ERβ, encoded by gene esr2, ten years later [1][2][3][4]. Although structurally closely related, expression patterns of estrogen receptors are different since ERα is widely expressed not only in reproductive organs in females and males (uterus, mammary gland, testes, epididymis) but also in non-reproductive organs such as the liver, heart and muscles; ERβ is mainly expressed in ovaries and the prostate gland. However, both receptors are expressed in bone tissue [5][6]. As members of the nuclear receptor superfamily, ERα and ERβ present six structural domains, A to F, a DNA-binding domain (DBD) and a ligand binding domain (LBD), as well as two Activating Functions, AF1 and AF2, involved in cofactor recruitment and in fine chromatin remodeling and gene transcription [7].

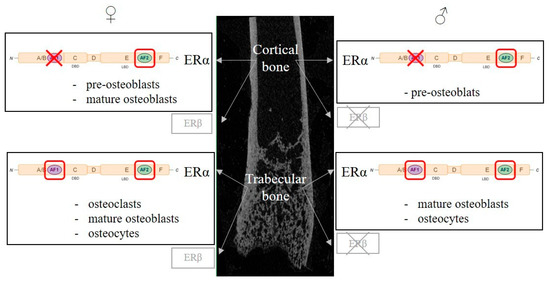

Murine models, deficient for ERα and ERβ, have allowed the study of the respective roles of each receptor in bone tissue. Results from the first studies, published in the early 2000s, have to be considered with caution since the murine model initially used (ERα and ERβ-Neo-KO) are not complete functional knockouts and still express truncated forms of ERα able to bind E2 [8][9]. New models, totally deficient in ERα (ERα−/−) and ERβ (ERβ−/−), have since been developed [10]. A first study in intact female and male mice showed that ERα deletion was associated with reduced bone turnover and increased trabecular bone volume in both genders. ERβ deletion had the same effects but only in female mice and the deletion of both receptors caused a drop in trabecular bone volume and turnover. ERα−/− mice exhibited strongly increased levels of circulating E2 and testosterone in females and males, resulting from a profound disruption of endocrine feedback loops [11]. To better understand the effects of ER deletion, gonadectomy was performed and associated with a reduction in all bone parameters (BMD, BV/TV, cortical thickness) and an increased bone turnover. E2 systemic administration could not restore bone features in ERα−/− female and male mice in contrast to wildtype (WT). In contrast, ERβ−/− mice had a similar response to E2 as WT [12], showing the prominent role of ERα in bone responses to estrogen in both males and females, while ERβ only has a minor protective role in females and none in males [11][12] (Figure 2). As in long bones and vertebrae, ERα is also necessary for E2’s protective effects in the mandible at alveolar, cortical and trabecular sites, whereas ERβ is dispensable [13]. ERαβ−/− mice, allowing the study of the possible compensatory role of one ER or the other in single-gene KO models (ERα−/− and ERβ−/−), exhibit a similar bone phenotype to ERα−/− mice, showing that ERβ is not sufficient to compensate for ERα actions in ERα−/− mice and that ERα is truly the central actor in estrogen osteoprotective effects [12].

Figure 2. Regulation of bone metabolism by estrogen receptors, cellular and molecular aspects. Estrogen’s protective effects on trabecular and cortical bone are mainly mediated by Estrogen Receptor α (ERα) in both females and males, while ERβ only plays a minor role in female and none in male. ERα belongs to the nuclear receptor superfamily and exerts its transcriptional activity though two activating functions (AFs), AF1 and AF2. Both AF1 and AF2 functions are necessary to mediate estrogen effects, whereas, in the cortical compartment, only AF2 function is necessary in females and males. Genetic murine models have allowed the study of the role of ERα in bone cells (osteoclasts, osteoblasts and osteocytes). For each bone compartment and sex, the cell types involved in estrogen’s protective effects are indicated. A red box highlights essential ERα subfunctions in each cell type, whereas a red X indicates the dispensable ERα subfunction.

However, constitutive ERα inactivation could lead to important developmental changes that may alter the adult mouse phenotype, although ERα appears to play a minor, if any, role in the development of most tissues, including those of the reproductive organs. To avoid this bias and study the E2 actions on ERα in adults, a team recently used an ERα-deficient tamoxifen-inducible mouse model [14]. In this model, trabecular responses to E2 treatment after ovariectomy and bone turnover are reduced but cortical response is maintained. Normal cortical responses to E2 in mutant mice may be explained by ERβ involvement either locally in bone tissue or by indirect effects in other tissues. For instance, estrogen receptors are expressed in several brain regions, and E2 is able to regulate cortical bone mass in female mice via indirect central nervous system mechanisms [15][16].

2. Estrogen Receptors in Bone Cells

The development of mouse models with conditional targeted deletion of ERs using the Cre-loxP system allowed the definition of more precise estrogen cellular targets in bone physiology. The expression of a Cre-recombinase controlled by the promotors of genes expressed specifically in targeted cell types or tissues results in the deletion of a genomic region of interest (here, crucial sequences of Esr1 or Esr2) flanked by two LoxP sites. Several models have been used to mainly study the role of ERα but also that of ERβ in bone cells (Table 1, Figure 2).

Table 1. ERα role in bone cells and the impact of its selective deletion in trabecular and cortical bone compartments in female and male mice.

| Targeted Cells | Osteoclasts | Osteoblasts | Osteocytes | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differentiation Stage | Myeloid Progenitors | Mature Osteoclasts | Pluripotent Mesenchymal Progenitors | Osteoblastic Progenitors | Mature Matrix Maturation | Mature Mineralization | NA | |||||||

| gene promotor | LysM | CtsK | Prx1 | Osx1 | Col1a1 | Ocn | Dmp1 | |||||||

| gender | female | male | female | male | female | male | female | male | female | male | female | male | female | male |

| trabecular bone | ↘ | ↔ | ↘ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↘ | ↔ [17] ↘ [18] |

↔ [19] ↘ [20] |

↘ |

| cortical bone | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↘ | ↘ * | ↘ | ↘ * | ↔ | ↔ | ↘ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ |

| references | [21] | [22] | [23] | [23] | [24] | [24] | [24] | [22] | [24] | [24] | [17][18][25] | [17][18] | [19][20] | [19] |

↔ no effect; ↘ bone mass reduction; * transient effect.

The deletion of ERα under the control of the cathepsine K (CtsK) promoter, specifically expressed in mature osteoclasts, was associated with trabecular bone loss in 12-week-old female mice but not in males [23]. Ovariectomy caused minor supplemental bone loss and E2 treatment restored trabecular bone mass but had no impact on the cortical compartment. Trabecular bone mass reduction was associated in CtsK-Cre+Erαlox/lox mice with increased osteoclast number and bone turnover in trabecular bone. A second model targeting myeloid osteoclast precursors under the control of the lysozyme M (LysM) promoter showed similar results. While female mutated mice exhibited an increased number of osteoclastic progenitors in bone marrow and differentiated osteoclasts in vertebrae, they had altered trabecular bone mass and microarchitecture, but no effect was observed in cortical bone [21]. In contrast, LysM-Cre+ERαlox/lox males had a similar bone phenotype to WT mice in both trabecular and cortical compartments [22].

ERα deletion in mesenchymal pluripotent osteoblast progenitors under the control of the Prx1 gene promoter (thus in all the following differentiation stages) was characterized by reduced cortical bone thickness and periosteal bone formation in female mice [24]. In contrast to WT mice, ovariectomy in Prx1-Cre+ERαlox/lox female mice did not induce supplemental cortical bone loss and was not associated with increased osteoclast number at the endocortical bone surface in femurs. In male mice, cortical bone mass was transitorily reduced at 8 weeks of age but was similar to WT at 22 weeks of age. Trabecular bone was unaffected in mutant females and males. Bone marrow cellular culture from Prx1-Cre+ERαlox/lox mice showed reduced osteoblast number and activity as evidenced by reduced expression of osteoblast differentiation markers Runx2, Osx, Col1a1 and Bglap [24]. ERβ deletion at the same stage of osteoblastic differentiation was associated with increased trabecular bone mass in female mice [26]. Female mice with ERα inactivation at a more advanced differentiation stage, in osteoblast progenitors present in bone-forming regions, under the control of the Osx1 (also called Sp7) gene promotor, had a similar bone phenotype and osteogenesis alteration [24]. Male Osx1-Cre+ERαlox/lox mice also had transiently reduced cortical bone mass and trabecular bone was not affected [22]. Transiently reduced cortical bone mass in males seems to reflect a delay in cortical bone mass acquisition during puberty since adult mice have normal cortical bone mass, suggesting that the action of androgens mediated by androgen receptors compensates for the absence of ERα. Finally, the targeted deletion of ERα in terminal osteoblastic differentiation in mature osteoblasts and osteocytes, controlled by the Col1a1 gene promoter, had no effect on trabecular and cortical bone in neither female nor male mice [24]. However, other teams invalidated ERα in mature osteoblasts using a different gene promoter encoding for OCN, and had different results [17][18][25]. In these studies, mutant female mice exhibited reduced trabecular bone mass and cortical thickness in femurs, tibia and vertebrae and reduced bone turnover marked by a limited number of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. No effect of ERα inactivation was observed in male mice [17][18][25]. These discrepancies may be explained by the use of different Cre models in which promoters are engaged in different chronological expression cellular effects. The Col1a1-Cre model targets osteoblasts during bone matrix maturation and Ocn-Cre targets osteoblasts later on, during bone matrix mineralization. Finally, ERα inactivation in osteocytes using Dmp1-Cre was associated with conflicting results [19][20]. One study found reduced trabecular bone mass and no cortical alteration [20], whereas another showed no bone phenotype in intact 12-week-old female mice [19]. This difference may be explained by the use of ERα-floxed mice with different genetic backgrounds. Moreover, it is important to stress that a recent study using flow cytometry and high-resolution microscopy showed that Ocn-Cre and Dmp1-Cre models do not only target mature osteoblasts and osteocytes but also affect broader stromal cell populations than initially considered. Results from Ocn-Cre+ERαlox/lox and Dmp1-Cre+ERαlox/lox mice must then be interpretated with caution [27].

An alternative approach to study the role of ERα in bone tissue consists in the use of hematopoietic chimeras. The reconstruction of lethally irradiated ERα−/− mice with bone marrow from ERα+/+ mice shows that ERα is necessary in non-hematopoietic cells, including osteoblasts, to mediate E2 effects on trabecular and cortical bone compartments [28]. A reverse bone marrow transplant from ERα−/− into WT mice showed that E2 effects on cortical and trabecular bone are enhanced by ERα in the hematopoietic compartment, suggesting that ERα expression in hematopoietic cells potentiates E2 bone-protective effects but only in the presence of ERα in non-hematopoietic cells [28]. Conflicting results with cell-specific inactivation of ERα using the Cre-Lox system may be explained by the fact that bone marrow transplants involve other cells than osteoblasts and osteoclast precursors. Indeed, several cell types of hematopoietic origin, beside osteoclasts, are involved in the estrogenic regulation of bone mass, including T and B lymphocytes [29][30]. A recent study showed that E2 effects on T lymphocytes are indirect since specific ERα deletion under the control of the Lck gene promoter had no effect on trabecular and cortical bone responses to ovariectomy and E2 treatment in female mice [31]. Moreover, mice with a deletion of ERα specifically in B lymphocytes have a similar bone phenotype to normal controls [32]. Results from the last two studies show that ERα signaling in T and B cells seems to be dispensable for bone loss caused by estrogen deficiency and that E2 effects on bone do not directly target those cells types and are more likely to be indirect.

The use of conditional deletion mice models of ERα in different bone cells showed that estrogen’s protective effects on trabecular and cortical bone compartments involve different cell types. E2 bone-protective effects on trabecular bone are mediated via direct actions on osteoclasts in female mice. ERα in osteoblast progenitors has a major role in cortical bone mass acquisition in female mice, whereas ERα in osteoblast mesenchymal precursors is involved in estrogen’s protective actions against endocortical bone resorption.

3. Nuclear vs. Non-Nuclear Erα-Mediated Pathways

In its inactive state, ERα is distributed in the nucleus, cytoplasm and plasma membrane in varying proportions, depending cell type. Ligand fixation on the receptor induces two major signaling pathways, nuclear/genomic ERα and membrane/non-genomic ERα.

In nuclear-initiated pathways, ligand fixation induces ERα dimerization and translocation to the nucleus, but in numerous cells, significant amounts of ERα appear to be present in the nucleus even in the absence of any ligand. In the nucleus, the ERα dimer interacts with specific promotors of target genes on precise sequences called estrogen response elements (EREs; ERE-dependent, “classical” pathway) or in interaction with other transcription factors such as AP-1 or SP1 bound to very specific DNA sequences (ERE-independent pathway). A third nuclear-initiated pathway is ligand independent, as ERα can be indirectly activated by growth factors like EGF or IGF-1. The fixation to their respective transmembrane receptor activates intracellular kinases able to phosphorylate ERα, modulating its interactions with specific cofactors [7]. ERα AF1 and AF2’s transactivating functions are able to act either synergically or independently to control target gene transcription. AF1 and AF2’s activities are finely controlled by transcription cofactor availability, cell type and the nature of the regulated promotor [7]. In order to study the respective roles of AF1 and AF2, mice models lacking one or the other have been developed [33][34]. In bone tissue, ERαAF1 is necessary to mediate E2’s protective effects on trabecular bone in both females and males but is only partly necessary in the cortical compartment. ERαAF2 is necessary in both the cortical and trabecular compartment to elicit full E2 effects in vertebrae and femurs in both genders; in the mandible, E2’s effects on alveolar, trabecular and cortical compartments are also mediated by ERαAF2 when a dose effect can be studied precisely thanks to an appropriate pellet to deliver accurate E2 doses [13][35][36][37] (Table 2, Figure 2).

Table 2. Genetic and pharmacological approaches to study the roles of ERs and their subfunctions in bone tissue regulation.

| Trabecular Bone | Cortical Bone | Alveolar Bone | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Model | Treatment | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | References |

| WT | E2 | ↗↗ | ↗↗ | ↗↗ | ↗↗ | ↗↗ | NT | [12][13] |

| EDC | ↔ | NT | ↗ | NT | ↗ | NT | [13][38] | |

| PaPEs | NT | NT | NT | NT | ↗ | NT | [13] | |

| ERα−/− | E2 | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | NT | [12][13] |

| ERβ−/− | E2 | ↗ | ↗↗ | ↗ | ↗↗ | ↗↗ | NT | [12][13] |

| ERα AF1° | E2 | ↔ | ↔ | ↗↗ | ↗↗ | NT | NT | [35][36] |

| ERα AF2° | E2 | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | NT | [13][35][36] |

| C451A-ERα | E2 | ↗ | ↗ | ↗ | ↗ | ↗ | NT | [13][39][40] |

↔ no effect; ↗↗ steep bone mass increase; ↗ small bone mass increase; WT: Wild Type; ER: Estrogen Receptor; AF: Activcating Function; E2: 17β-estradiol; EDC: estrogen–dendrimer conjugate; PaPEs: pathway preferential estrogens; NT: not tested.

Besides classically described nuclear effects, ERα signaling pathways can be initiated at the plasma membrane (membrane-initiated steroid signaling, MISS). Membrane signaling of steroid receptors has been shown in several cell types, including osteoblasts and osteoclasts [104]. Two murine models have been developed to investigate the physiological roles of ERα-MISS in vivo. The first one consists in a point mutation of ERα at its palmitoylation site, necessary for its addressing to the plasma membrane, and C451A-ERα mice exhibit a membrane-specific loss of function of ERα [105,106]. Two studies show that in the axial skeleton, E2’s effects on trabecular bone are strongly dependent on membrane ERα (mERα) whereas in long bones, cortical and trabecular E2’s effects are only partly dependent on mERα in growing and adult female mice [102,103]. Moreover, ERα-MISS seems to impact osteoblasts but not the osteoclast lineage in response to E2 [102]. In the mandible, bone response to E2 treatment is slightly but significantly reduced in alveolar, trabecular and cortical compartments [77]. These results show that mERα is necessary to elicit full E2 bone-protective effects. The second model, R264A-ERα, consisting in a point mutation of ERα in a sequence necessary for its interaction with proteins at the plasma membrane, is fertile in contrast to C451A-ERα but unable to display classical membrane-initiated E2 effects (accelerated reendothelialization, arterial dilation) [107]. Surprisingly, R264A-ERα mice exhibit similar bone responses to ovariectomy and E2 treatment to WT (BMD, cortical thickness, trabecular bone mass) [108]. Thus, it seems that the functional consequences of this second ERα point mutation appear to be restricted to endothelial cells, without impacting on the mERα in other cell types.

Besides the use of genetically modified models, another approach to study the respective roles of nuclear and membrane ERα is pharmacological. Despite a weak agonist activity for ERα and ERβ, estetrol (E4), an estrogen produced by fetal liver, has similar effects to E2 on uterine gene expression and epithelial proliferation when administered in high doses to female mice and prevents atheroma. All these E4 actions are known to involve nuclear ERα action, whereas E4 is unable to activate endothelial (NOS) and to accelerate endothelial healing, which are MISS-dependent effects [109,110,111,112]. Thus, E4 is classified as a natural estrogen with selective action in tissues (NEST) displaying nuclear ERα activation only. E4 administration to osteoporotic female rats was associated to increased bone mineral density and bone strength in a dose-dependent manner [113]. E4 has been studied in human trials as a candidate for menopause hormonal therapy; besides estrogenic effects on reproductive tissues (vaginal epithelium, endometrium) and hot flushes, it has dose-dependent estrogenic effects on bone with a reduction of osteocalcin (bone formation marker) and CTX-1 (bone resorption marker) serum concentrations in postmenopausal women [1,114,115]. As part of studies regarding prostate cancer, E4 administration to healthy men reduces bone turnover markers, although not significantly for osteocalcin [116].

While E4 activates ERα nuclear pathways, two other chemical compounds are able to only elicit ERαMISS, estrogen–dendrimer conjugate (EDC) and pathway preferential estrogens (PaPEs). EDC consists of ethinyl-estradiol attached to a large, positively charged, nondegradable poly(amido)amine dendrimer preventing it from translocating to the nucleus [117]. EDC promotes endothelial protection in mice since it increases NO production and accelerates reendothelization without inducing uterine or breast cancer growth [118]. In bone tissue, EDC administration is associated with increased femoral and vertebral cortical bone mass and bone strength. However, it does not seem to have effects on vertebral trabecular bone in either female or male mice [101,119]. In the mandible, EDC increases alveolar bone mass but has no effects on trabecular and cortical bone [77]. More recently, PaPEs originating from the rearrangement of E2 steroidal structure have been developed. PaPEs form complexes with ER with a very short lifespan, sufficient to selectively activate membrane-initiated ER pathways but too transient to maintain nuclear activity; they exert beneficial effects in metabolic tissues and the vasculature [120]. PaPEs have similar effects on mandibular bone to EDC, with increased alveolar bone mass and no effects on trabecular and cortical bone in female mice [77]. PaPEs’ effects on vertebral and femoral bone in both females and males have not been determined yet.

Results from genetical approaches targeting nuclear loss-of-function ERα-AF2° on the one hand, and pharmacological approaches with EDC and PaPEs on the other hand, may seem contradictory. Selective activation of ERαMISS with EDC has effects on long and mandibular bone [13][38] while E2’s beneficial actions are totally abrogated in nuclear ERα-AF2°-deficient mice [36]. Nevertheless, it has been shown that nuclear ERα-AF1 is necessary for EDC effects, emphasizing the importance of the crosstalk between nuclear and membrane ERs to relay estrogen’s beneficial effects on bone [41]. Moreover, one can imagine that part of EDC and PaPEs’ actions could involve an activation of both AF1 and AF2, implying another level of interaction between nuclear and membrane ERα.

4. Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators

Depending on the ligand nature, ERs adopt a specific conformation. Following the fixation of an agonistic ligand such as E2, the position of helix 12 determines the formation of an AF2 region available for transcriptional coactivators to bind on to. In contrast, when an antagonist binds to the receptor, the helix 12 position blocks cofactor recruitment and prevents gene transcription. Between those extremes, the receptor–ligand complex adopts a unique conformation for each ER ligand [7]. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are synthetic pharmacological compounds, lacking an estrogen steroidal structure but exhibiting a tertiary structure, able to bind onto ERs; they can selectively elicit estrogen’s protective effects (on bone tissue, the cardiovascular system or metabolism) without triggering deleterious impacts (after menopause, on uterus or mammary glands). Several SERMs are thus employed in clinical practice to treat and prevent breast cancer, osteoporosis or menopause symptoms [42][43]. Tamoxifen (Tam), was developed in the 1970s for breast cancer treatment. It increases cortical and trabecular bone mass in both female and male intact mice and partially blocks orchidectomy-induced trabecular bone loss in male mice [44][45][46][47]. Raloxifene (Ral) is approved for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women since it reduces the risk of vertebral fractures by 30–50% [48]. Its administration increases trabecular bone mass and mineral density in male mice and enhances vertebral trabecular bone mass and femoral cortical bone mass in female mice [35][47][49]. More recently, two other SERMs, lasofoxifen (Las) and bazedoxifene (Bza) have been approved in Europe for the treatment or postmenopausal osteoporosis; they decrease the risk of vertebral as well as non-vertebral fractures [50][51]. In mice, whereas Las increases trabecular bone mass in the axial skeleton and both trabecular and cortical bone mass in the appendicular skeleton, Bza only enhances trabecular bone mass in the axial skeleton in both genders [35][47][49]. It has been recently shown that ERα-AF1 is necessary for the bone estrogenic effects of Ral, Las and Bza in female and male mice [35][49].

5. Mechanical Loading

Mechanical strains are considered to be a critical regulator of bone homeostasis; they determine bone shape, structure and mass and affect bone remodeling in favor of bone formation. For example, mechanical unloading resulting from weightlessness during space flights is associated with reduced trabecular and cortical bone mineral density and accelerated bone resorption [52]. Thus, during growth, children with moderate physical activity exhibit greater bone mineral content than sedentary children [53].

Regarding the osteogenic effects of mechanical loading, several studies reveal an implication of ERα that would act independently of any ligand. Indeed, the application of mechanical tensions on osteoblast and osteocyte cultures promotes their activation and proliferation via ERα [54][55]. Moreover, a study about the effects of the interactions between ERα gene polymorphism and physical activity on bone mass modulation in humans suggests that genetic variants of the esr 1 locus could modulate bone tissue mechanosensitivity, supporting a major role of bone cell ERα in bone adaptation to mechanical strains [56].

Several studies showed that ERα is involved in vivo in the osteogenic effects of mechanical strains in a ligand-independent manner [57][58]. In female ERα−/− mice, osteogenic response to mechanical loading is reduced in cortical but not trabecular bone compared to WT; conversely, in males, ERα inactivation is associated with increased osteogenic response to mechanical loading in both bone compartments. ERβ−/− female and male mice exhibit increased osteogenic responses to loading in cortical but not trabecular bone [57]. In that respect, ERα and ERβ seem to have opposite effects and may be in competition for the regulation of bone remodeling by mechanical strains in female mice. Finally, ERα-AF1 is necessary to mediate osteogenic effects of mechanical loading, whereas ERα-AF2 is not required in female mice [58]. This again suggests a key role of E2-independent actions of ERα, potentially through activation of ERα-AF1 that is the target of growth factors. The involvement of ERα in the mechanical strains of bone homeostasis should undoubtedly be further studied in the future to optimize the approaches to fight bone demineralization and the risk of bone fracture.

References

- Green, S.; Walter, P.; Kumar, V.; Krust, A.; Bornert, J.-M.; Argos, P.; Chambon, P. Human oestrogen receptor cDNA: Sequence, expression and homology to verb-A. Nat. Cell Biol. 1986, 320, 134–139.

- Greene, G.L.; Gilna, P.; Waterfield, M.; Baker, A.; Hort, Y.; Shine, J. Sequence and expression of human estrogen receptor com-plementary DNA. Science 1986, 231, 1150–1154.

- Kuiper, G.; Enmark, E.; Pelto-Huikko, M.; Nilsson, S.; Gustafsson, J.-A. Cloning of a Novel Estrogen Receptor Expressed in Rat Prostate and Ovary. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 5925–5930.

- Mosselman, S.; Polman, J.; Dijkema, R. ERβ: Identificatino and Characterization of a Novel Human Estrogen Receptor. FEBS Lett. 1996, 392, 49–53.

- Cooke, P.S.; Nanjappa, M.K.; Ko, C.; Prins, G.S.; Hess, R.A. Estrogens in Male Physiology. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 995–1043.

- Couse, J.F.; Lindzey, J.; Grandien, K.; Gustafsson, J.A.; Korach, K.S. Tissue distribution and quantitative analysis of estrogen receptor-alpha (ERalpha) and estrogen receptor-beta (ERbeta) messenger ribonucleic acid in the wild-type and ERalpha-knockout mouse. Endocrinology 1997, 138, 4613–4621.

- Arnal, J.-F.; Lenfant, F.; Metivier, R.; Flouriot, G.; Henrion, D.; Adlanmerini, M.; Fontaine, C.; Gourdy, P.; Chambon, P.; Katzenellenbogen, B.; et al. Membrane and Nuclear Estrogen Receptor Alpha Actions: From Tissue Specificity to Medical Implications. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 1045–1087.

- Lindberg, M.K.; Alatalo, S.L.; Halleen, J.M.; Mohan, S.; A Gustafsson, J.; Ohlsson, C. Estrogen receptor specificity in the regulation of the skeleton in female mice. J. Endocrinol. 2001, 171, 229–236.

- Movérare, S.; Venken, K.; Eriksson, A.-L.; Andersson, N.; Skrtic, S.; Wergedal, J.; Mohan, S.; Salmon, P.; Bouillon, R.; Gustafsson, J.-A.; et al. Differencial Effects on Bone of Estrogen Receptor α and Androgen Receptor Activation in Orchidectomized Adult Male Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 13573–13578.

- Dupont, S.; Krust, A.; Gansmuller, A.; Dierich, A.; Chambon, P.; Mark, M. Effect of single and compound knockouts of estrogen receptors alpha (ERalpha) and beta (ERbeta) on mouse reproductive phenotypes. Development 2000, 127, 4277–4291.

- Sims, N.A.; Dupont, S.; Krust, A.; Clement-Lacroix, P.; Minet, D.; Resche-Rigon, M.; Gaillard-Kelly, M.; Baron, R. Deletion of estrogen receptors reveals a regulatory role for estrogen receptors-beta in bone remodeling in females but not in males. Bone 2002, 30, 18–25.

- Sims, N.A.; Clément-Lacroix, P.; Minet, D.; Fraslon-Vanhulle, C.; Gaillard-Kelly, M.; Resche-Rigon, M.; Baron, R. A functional androgen receptor is not sufficient to allow estradiol to protect bone after gonadectomy in estradiol receptor–deficient mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1319–1327.

- Vinel, A.; Coudert, A.E.; Buscato, M.; Valera, M.C.; Ostertag, A.; Katzenellenbogen, J.A.; Katzenellenbogen, B.S.; Berdal, A.; Babajko, S.; Arnal, J.F.; et al. Respective role of membrane and nu-clear estrogen receptor (ER) α in the mandible of growing mice: Implications for ERα modulation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2018, 33, 1520–1531.

- Ohlsson, C.; Farman, H.H.; Gustafsson, K.L.; Wu, J.; Henning, P.; Windahl, S.H.; Sjögren, K.; Gustafsson, J.-Å.; Movérare-Skrtic, S.; Lagerquist, M.K. The effects of estradiol are modulated in a tissue-specific manner in mice with inducible inactivation of ERα after sexual maturation. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2020, 318, E646–E654.

- Idelevich, A.; Baron, R. Brain to bone: What is the contribution of the brain to skeletal homeostasis? Bone 2018, 115, 31–42.

- Farman, H.H.; Windahl, S.H.; Westberg, L.; Isaksson, H.; Egecioglu, E.; Schele, E.; Ryberg, H.; Jansson, J.O.; Tuukkanen, J.; Koskela, A.; et al. Female Mice Lacking Estrogen Receptor-α in Hypothalamic Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) Neurons Display Enhanced Estrogenic Response on Cortical Bone Mass. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 3242–3252.

- Melville, K.; Kelly, N.; Surita, G.; Buchalter, D.; Schimenti, J.; Main, R.; Ross, F.P.; van der Meulen, M.C. Effects of Deletion of ER α in Osteoblast-Lineage Cells on Bone Mass and Adptation to Mechanical Loading Differ in Female and Male Mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015, 30, 1468–1480.

- Määttä, J.A.; Büki, K.G.; Gu, G.; Alanne, M.H.; Vääräniemi, J.; Liljenbäck, H.; Poutanen, M.; Härkönen, P.; Väänänen, K. Inactivation of estrogen receptor α in bone-forming cells induces bone loss in female mice. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 478–488.

- Windahl, S.H.; Börjesson, A.E.; Farman, H.H.; Engdahl, C.; Movérare-Skrtic, S.; Sjögren, K.; Lagerquist, M.K.; Kindblom, J.M.; Koskela, A.; Tuukkanen, J.; et al. Estrogen receptor-α in osteocytes is important for trabecular bone formation in male mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 2294–2299.

- Kondoh, S.; Inoue, K.; Igarashi, K.; Sugizaki, H.; Shirode-Fukuda, Y.; Inoue, E.; Yu, T.; Takeuchi, J.K.; Kanno, J.; Bonewald, L.F.; et al. Estrogen receptor α in osteocytes regulates trabecular bone formation in female mice. Bone 2014, 60, 68–77.

- Martin-Millan, M.; Almeida, M.; Ambrogini, E.; Han, L.; Zhao, H.; Weinstein, R.S.; Jilka, R.L.; O’Brien, C.A.; Manolagas, S.C. The Estrogen Receptor-α in Osteoclasts Mediates the Protective Effects of Estrogens on Cancellous but Not Cortical Bone. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010, 24, 323–334.

- Ucer, S.; Iyer, S.; Bartell, S.M.; Martin-Millan, M.; Han, L.; Kim, H.-N.; Weinstein, R.S.; Jilka, R.L.; O’Brien, C.A.; Almeida, M.; et al. The Effects of Androgens on Murine Cortical Bone Do Not Require AR or ERα Signaling in Osteoblasts and Osteoclasts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015, 30, 1138–1149.

- Nakamura, T.; Imai, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Sato, S.; Takeuchi, K.; Igarashi, K.; Harada, Y.; Azuma, Y.; Krust, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; et al. Estrogen Prevents Bone Loss via Estrogen Receptor α and Induction of Fas Ligand in Osteoclasts. Cell 2007, 130, 811–823.

- Almeida, M.; Iyer, S.; Martin-Millan, M.; Bartell, S.; Han, L.; Ambrogini, E.; Onal, M.; Xiong, J.; Weinstein, R.; Jilka, R.; et al. Estrogen Receptor-α Signaling in Osteoblast Pro-genitors Stimulates Cortical Bone Accrual. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 394–404.

- Melville, K.M.; Kelly, N.H.; Khan, S.A.; Schimenti, J.C.; Ross, F.P.; Main, R.P.; Van Der Meulen, M.C.H. Female Mice Lacking Estrogen Receptor-Alpha in Osteoblasts Have Compromised Bone Mass and Strength. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014, 29, 370–379.

- Nicks, K.M.; Fujita, K.; Fraser, D.G.; McGregor, U.; Drake, M.T.; McGee-Lawrence, M.E.; Westendorf, J.J.; Monroe, D.G.; Khosla, S. Deletion of Estrogen Receptor Beta in Osteoprogenitor Cells Increases Trabecular but Not Cortical Bone Mass in Female Mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2016, 31, 606–614.

- Zhang, J.; Link, D.C. Targeting of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells by Cre-Recombinase Transgenes Commonly Used to Target Osteoblast Lineage Cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2016, 31, 2001–2007.

- Henning, P.; Ohlsson, C.; Engdahl, C.; Farman, H.; Windahl, S.H.; Carlsten, H.; Lagerquist, M.K. The effect of estrogen on bone requires ERα in nonhematopoietic cells but is enhanced by ERα in hematopoietic cells. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2014, 307, E589–E595.

- Pacifici, R. Role of T cells in ovariectomy induced bone loss-revisited. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012, 27, 231–239.

- Horowitz, M.C.; Fretz, J.A.; Lorenzo, J.A. How B cells influence bone biology in health and disease. Bone 2010, 47, 472–479.

- Gustafsson, K.L.; Nilsson, K.H.; Farman, H.H.; Andersson, A.; Lionikaite, V.; Henning, P.; Wu, J.; Windahl, S.H.; Islander, U.; Movérare-Skrtic, S.; et al. ERα expression in T lymphocytes is dispensable for estrogenic effects in bone. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 238, 129–136.

- Fujiwara, Y.; Piemontese, M.; Liu, Y.; Thostenson, J.D.; Xiong, J.; O’Brien, C.A. RANKL (Receptor Activator of NFκB Ligand) Pro-duced by Osteocytes Is Required for the Increase in B Cells and Bone Loss Caused by Estrogen Deficiency in Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 24838–24850.

- Billon-Galés, A.; Fontaine, C.; Filipe, C.; Douin-Echinard, V.; Fouque, M.-J.; Flouriot, G.; Gourdy, P.; Lenfant, F.; Laurell, H.; Krust, A.; et al. The transactivating function 1 of estrogen receptor α is dispensable for the vasculoprotective actions of 17β-estradiol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 2053–2058.

- Billon-Galés, A.; Krust, A.; Fontaine, C.; Abot, A.; Flouriot, G.; Toutain, C.; Berges, H.; Gadeau, A.-P.; Lenfant, F.; Gourdy, P.; et al. Activation function 2 (AF2) of estrogen receptor-α is required for the atheroprotective action of estradiol but not to accelerate endothelial healing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 13311–13316.

- Börjesson, A.E.; Farman, H.H.; Engdahl, C.; Koskela, A.; Sjögren, K.; Kindblom, J.M.; Stubelius, A.; Islander, U.; Carlsten, H.; Antal, M.C.; et al. The role of activation functions 1 and 2 of estrogen receptor-α for the effects of estradiol and selective estrogen receptor modulators in male mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 1117–1126.

- Börjesson, A.E.; Windahl, S.H.; Lagerquist, M.K.; Engdahl, C.; Frenkel, B.; Movérare-Skrtic, S.; Sjögren, K.; Kindblom, J.M.; Stubelius, A.; Islander, U.; et al. Roles of transactivating func-tions 1 and 2 of estrogen receptor-alpha in bone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 6288–6293.

- Fontaine, C.; Buscato, M.; Vinel, A.; Giton, F.; Raymond-Letron, I.; Kim, S.H.; Katzenellenbogen, B.S.; Katzenellenbogen, J.A.; Gourdy, P.; Milon, A.; et al. The tissue-specific effects of different 17β-estradiol doses reveal the key sensitizing role of AF1 domain in ERα activity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2020, 505, 110741.

- Bartell, S.M.; Han, L.; Kim, H.-N.; Kim, S.H.; Katzenellenbogen, J.A.; Katzenellenbogen, B.S.; Chambliss, K.L.; Shaul, P.W.; Roberson, P.K.; Weinstein, R.S.; et al. Non-Nuclear–Initiated Actions of the Estrogen Receptor Protect Cortical Bone Mass. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 27, 649–656.

- Vinel, A.; Hay, E.; Valera, M.C.; Buscato, M.; Adlanmerini, M.; Guillaume, M.; Cohen-Solal, M.; Ohlsson, C.; Lenfant, F.; Arnal, J.F.; et al. Role of ERα in the Effect of Estradiol on Cancel-lous and Cortical Femoral Bone in Growing Female Mice. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 2533–2544.

- Gustafsson, K.L.; Farman, H.; Henning, P.; Lionikaite, V.; Movérare-Skrtic, S.; Wu, J.; Ryberg, H.; Koskela, A.; Gustafsson, J.-Å.; Tuukkanen, J.; et al. The role of membrane ERα signaling in bone and other major estrogen responsive tissues. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29473.

- Farman, H.H.; Gustafsson, K.L.; Henning, P.; Grahnemo, L.; Lionikaite, V.; Movérare-Skrtic, S.; Wu, J.; Ryberg, H.; Koskela, A.; Tuukkanen, J.; et al. Membrane estrogen receptor α is essential for estrogen signaling in the male skeleton. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 239, 303–312.

- Riggs, L.; Hartmann, L. Selective Estrogen-Receptor Modulators: Mechanisms of Action and Application to Clinical Practice. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 618–629.

- Pinkerton, J.V.; Conner, E.A. Beyond estrogen: Advances in tissue selective estrogen complexes and selective estrogen receptor modulators. Climacteric 2019, 22, 140–147.

- Zhong, Z.A.; Sun, W.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Lay, Y.-A.E.; Lane, N.E.; Yao, W. Optimizing tamoxifen-inducible Cre/loxp system to reduce tamoxifen effect on bone turnover in long bones of young mice. Bone 2015, 81, 614–619.

- Starnes, L.M.; Downey, C.M.; Boyd, S.K.; Jirik, F.R. Increased bone mass in male and female mice following tamoxifen administra-tion. Genesis 2007, 45, 229–235.

- Jardí, F.; Laurent, M.R.; Dubois, V.; Khalil, R.; Deboel, L.; Schollaert, D.; Bosch, L.V.D.; Decallonne, B.; Carmeliet, G.; Claessens, F.; et al. A shortened tamoxifen induction scheme to induce CreER recombinase without side effects on the male mouse skeleton. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 452, 57–63.

- Sato, Y.; Tando, T.; Morita, M.; Miyamoto, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Watanabe, R.; Oike, T.; Matsumoto, M.; Nakamura, M.; Miyamoto, T. Selective estrogen receptor modulators and the vitamin D analogue eldecalcitol block bone loss in male osteoporosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 482, 1430–1436.

- Kanis, J.A.; Cooper, C.; Rizzoli, R.; Reginster, J.Y. (IOF) SABotESfCaEAoOEatCoSAaNSotIOF. European guidance for the diagno-sis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos. Int. 2019, 30, 3–44.

- Börjesson, A.E.; Farman, H.H.; Movérare-Skrtic, S.; Engdahl, C.; Antal, M.C.; Koskela, A.; Tuukkanen, J.; Carlsten, H.; Krust, A.; Chambon, P.; et al. SERMs have substance-specific ef-fects on bone, and these effects are mediated via ErαAF-1 in female mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 310, E912–E918.

- Palacios, S.; Silverman, S.L.; de Villiers, T.J.; Levine, A.B.; Goemaere, S.; Brown, J.P.; De Cicco Nardone, F.; Williams, R.; Hines, T.L.; Mirkin, S.; et al. A 7-year randomized, placebo-controlled trial assessing the long-term efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: Effects on bone density and fracture. Menopause 2015, 22, 806–813.

- Cummings, S.R.; Ensrud, K.; Delmas, P.D.; LaCroix, A.Z.; Vukicevic, S.; Reid, D.M.; Goldstein, S.; Sriram, U.; Lee, A.; Thompson, J.; et al. Lasofoxifene in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 686–696.

- Vico, L.; Collet, P.; Guignandon, A.; Lafage-Proust, M.-H.; Thomas, T.; Rehailia, M.; Alexandre, C. Effects of long-term microgravity exposure on cancellous and cortical weight-bearing bones of cosmonauts. Lancet 2000, 355, 1607–1611.

- Klentrou, P. Influence of Exercise and Training on Critical Stages of Bone Growth and Development. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2016, 28, 178–186.

- Aguirre, J.I.; Plotkin, L.I.; Gortazar, A.R.; Millan, M.M.; O’Brien, C.A.; Manolagas, S.C.; Bellido, T. A Novel Ligand-independent Function of the Estrogen Receptor Is Essential for Osteocyte and Osteoblast Mechanotransduction. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 25501–25508.

- Galea, G.L.; Meakin, L.B.; Sugiyama, T.; Zebda, N.; Sunters, A.; Taipaleenmaki, H.; Stein, G.S.; Van Wijnen, A.J.; Lanyon, L.E.; Price, J.S. Estrogen Receptor α Mediates Proliferation of Osteoblastic Cells Stimulated by Estrogen and Mechanical Strain, but Their Acute Down-regulation of the Wnt Antagonist Sost Is Mediated by Estrogen Receptor β. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 9035–9048.

- Suuriniemi, M.; Mahonen, A.; Kovanen, V.; Alén, M.; Lyytikäinen, A.; Wang, Q.; Kröger, H.; Cheng, S. Association Between Exercise and Pubertal BMD Is Modulated by Estrogen Receptor α Genotype. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004, 19, 1758–1765.

- Saxon, L.K.; Galea, G.; Meakin, L.; Price, J.; Lanyon, L.E. Estrogen Receptors α and β Have Different Gender-Dependent Effects on the Adaptive Responses to Load Bearing in Cancellous and Cortical Bone. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 2254–2266.

- Windahl, S.; Saxon, L.; Börjesson, A.; Lagerquist, M.; Frenkel, B.; Henning, P.; Lerner, U.; Galea, G.; Meakin, L.; Engdahl, C.; et al. Estrogen Receptor-α Is Required of the Osteo-genic Response to Mechanical Loading in a Ligand-Independant Manner Involving Its Activatin Function 1 but Not 2. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 291–301.